Baby Oysters Listen for Safety

Air Date: Week of January 6, 2023

It appears that oyster larvae are attracted to the sounds of a healthy reef. (Photo: Petras Gagilas, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Coral reefs play a crucial role in managing tidal surges, creating habitat for other species, and improving water quality. But many oyster species including the Australian flat oyster are under threat. So, some scientists in Australia are looking into how baby oysters find an appropriate place to set up shop. Living on Earth’s Sophia Pandelidis has more on how sound may be key.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Not everyone likes them, but for aficionados there’s nothing quite as tasty as a freshly shucked oyster. And when it comes to managing tidal surges at the ocean’s edge, oyster reefs make a big difference. These reefs also create habitat for other species and as filter feeders oysters keep waters clear of excess algae and nutrients that might otherwise degrade water quality. Many oyster species including the Australian flat oyster are under threat. So, some scientists in Australia are looking into how baby oysters, otherwise known as spat, find an appropriate place to set up shop. And it turns out sound may be key. Living on Earth's Sophia Pandelidis has more.

[OCEAN SOUNDS]

PANDELIDIS: For a baby Australian flat oyster, the world beneath the waves can be a scary place.

When it first leaves the safety of its parent’s shell, an oyster larva is only around 170 microns long—that’s about as thick as two sheets of paper.

And if it hopes to be one of the lucky survivors out of millions of siblings, it better find a place to settle–fast.

Scientists are uncertain about how exactly these little larvae choose which way to go.

The “sizzling bacon” sound of snapping shrimp dominates the underwater soundscape of a thriving reef. (Photo: budak, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

But it’s possible that oysters use sound to navigate.

Oysters don’t have ears, but they can still interpret and react to sound by sensing with their bodies the way that sound waves rattle particles as they move through water.

[sounds of shipping motors (Source: Freesound, Mrthenoronha)]

PANDELIDIS: It is well-known that anthropogenic noise pollution can be disruptive to marine life. The sounds of shipping motors, offshore construction,

[offshore construction (Source: Freesound, Mrthenoronha)]

PANDELIDIS: And military SONAR.

[Sonar (Source: FreeSound, Breviceps)]

PANDELIDIS: Can be disorienting and sometimes lethal for underwater organisms.

Fish also make a wide variety of sounds, ranging from “purring” to “grunting.” (Photo: Stefan David, CamperCo.de, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

In fact, oysters have been shown to slow their feeding and growth rates–and even clamp their valves shut– when bombarded with these noises.

But oyster larvae have also been known to swim impressive distances towards a pleasing sound.

So, researchers at the University of Adelaide in Australia tried to find out if sound might even be a key to oyster restoration.

[snapping shrimp sound (Source: Dr. Dominic McAfee, University of Adelaide)]

PANDELIDIS: They set up a soundscape imitating a healthy reef– an ideal spot for an oyster to settle down– and played it on carefully positioned underwater speakers.

Sea urchins scrape algae off rocks with their teeth, adding yet another sound to the reef environment. (Photo: Diane Graham, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

[crackling continues]

PANDELIDIS: Snapping shrimp, which hide in the nooks and crannies of reefs, dominate this underwater orchestra.

[snapping shrimp in the clear]

PANDELIDIS: They create air bubbles that pop by snapping their claws together at roughly 60 miles per hour, making them one of the fastest moving creatures in the animal kingdom.

And while researchers say the shrimp take first chair in the underwater orchestra, other creatures add richness to the symphony.

[Fish sounds (Source: Research Paper: The sound of recovery: coral reef restoration success is detectable in the soundscape, from the Journal of Ecology, also given explicit permission and additional audio files from Dr. Timothy Lamont from the University of Exeter, lead researcher on the paper)]

PANDELIDIS: Fish that purr, grunt, whoop, and even honk make up the brass section.

Dominic McAfee, the lead researcher in the restoration project, holds one of the underwater speakers his team developed. (Photo: Dominic McAfee)

And grazing urchins, which scrape algae off rocks with their teeth, bring in the percussion.

[grazing urchins sound (Source: “Sea Urchin Grazing” on Vimeo, credit to Craig A Radford, University of Auckland, from whom I also got explicit permission)]

PANDELIDIS: Dr. Dominic McAfee, the lead researcher in the project, says his team even added non-animal elements

[Thunder sound (Source: Freesound, Simon Spiers)]

PANDELIDIS: Like lightning strikes and crashing waves to flesh out the acoustics here. And it’s worked.

McAfee and his team found that oyster recruitment increased significantly at sites near the reef-imitating speakers.

They saw 17,000 more larvae settled per square meter on boulders they placed near the speakers, as compared to settlement areas without the presence of added sound.

Many oyster species worldwide have been decimated by human activity.

And the Australian flat oysters were harvested to the point of near extinction over the last few centuries.

That’s bad news for water quality—oysters are crucial for filtering water in aquatic ecosystems.

Oysters can also form reefs that can act as natural barriers, protecting shorelines from severe storms.

So people have a vested interest in restoring a healthy oyster population.

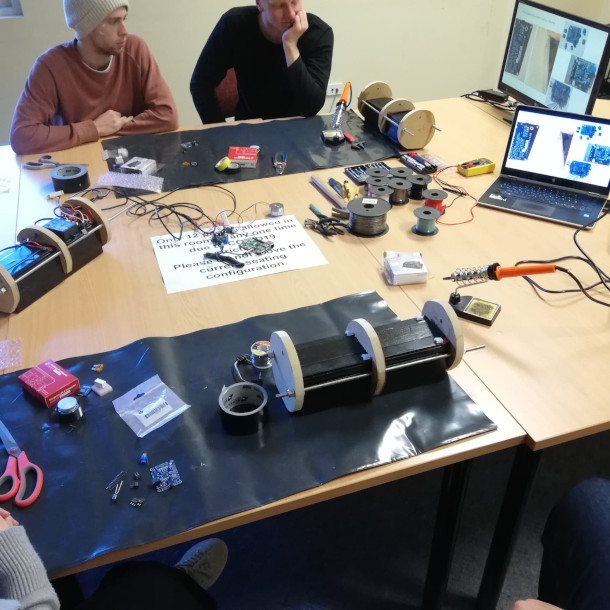

Dr. McAfee’s students build the speaker designed to attract oyster larvae to restoration sites. (Photo: Dominic McAfee)

In Australia national restoration efforts began in 2015, and the Adelaide researchers hope to include soundscapes in future restoration work.

[continue snapping shrimp, fish sounds]

PANDELIDIS: They are optimistic that an underwater symphony will be able to attract other species as well to improve their populations and create healthy reefs.

For Living on Earth, I’m Sophia Pandelidis.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth