January 6, 2023

Air Date: January 6, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Environment and the Law in 2023

View the page for this story

The case West Virginia v. EPA and the Inflation Reduction Act made 2022 a landmark year for environmental law. Pat Parenteau, former EPA regional counsel and emeritus professor at Vermont Law School, joins Host Steve Curwood to look ahead to environmental legal actions on the horizon in 2023, including Supreme Court clean water and other decisions, environmental justice implementation, and suits alleging climate racketeering. (11:21)

Auld Lang Syne

View the page for this story

This week, journalist Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood take some time to reflect on some lives we lost in 2022. From Living on Earth's former producer Lucia Small to the infamous climate change skeptic Pat Michaels, the two discuss the passing of individuals who made their mark on the environmental sector, for better or for worse. (08:31)

Midnight in the Everglades

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

Alligators have such gaping jaws you might wonder what they eat. For one group of researchers looking into this, the answers so far point to snails and amphibians like the giant salamanders known as amphiumas, rather than fish or hapless mammals that walk too close to swampy waters. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman spent a night in Florida’s Everglades with a team investigating this and shares his story. (07:34)

The Accidental Ecosystem

View the page for this story

Many non-human animals call cities home or take advantage of their abundant resources. In his 2022 book The Accidental Ecosystem: People and Wildlife in American Cities, environmental historian Peter Alagona explores how other species have found ways to live among us. He joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss how being more intentional about how we design and use our cities in the future can bring benefits for both humans and the wildlife we share these spaces with. (14:33)

Baby Oysters Listen for Safety

/ Sophia PandelidisView the page for this story

Coral reefs play a crucial role in managing tidal surges, creating habitat for other species, and improving water quality. But many oyster species including the Australian flat oyster are under threat. So, some scientists in Australia are looking into how baby oysters find an appropriate place to set up shop. Living on Earth’s Sophia Pandelidis has more on how sound may be key. (04:56)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230106 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Peter Alagona, Pat Parenteau

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman, Sophia Pandelelidis

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

We take a look at the year ahead for environmental laws and the Inflation Reduction Act.

PARENTEAU: Getting that money out the door, getting the money to work is now the challenge. We are so fortunate that the midterm elections did not turn over the control of the Senate. There's no way now that the Inflation Reduction Act is going to get whittled away.

CURWOOD: Also, uncovering some accidental ecosystems in our cities.

ALAGONA: We ended up getting a lot of wildlife in urban areas unintentionally. People started planting trees in cities in the 19th century, not because they were trying to attract squirrels. But because they thought it was going to be better for human health and well-being to have cities with trees, to have cities with shade.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Environment and the Law in 2023

The court's decision in West Virginia v. EPA found that the agency effectively does not have the power to regulate the mix of generation sources to address carbon dioxide emissions from power plants. (Photo: Susan Melkisethian, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

And I’m Steve Curwood.

2022 was a landmark year for environmental law, both in terms of court decisions and legislation, and now as 2023 gets underway there are even more legal actions and decisions on the horizon. These include protections for our climate, clean water and wildlife and moving the federal government from words to action. And to help us sort it out we turn now to Pat Parenteau, former EPA regional counsel and emeritus professor at Vermont Law School. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Pat!

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Steve. Good to be with you in 2023.

CURWOOD: Yeah, Happy New Year. Let's go over some of the standout court cases first from last year. What was decided in 2022 that, well, we'll be thinking about some more in 2023?

PARENTEAU: Well, the big one, of course, was West Virginia v EPA, which was the Supreme Court striking down the Obama Clean Power Plan regulating greenhouse gas emissions from steam electric power plants. And the way in which the Court did it is the most troubling thing about the decision. We were not surprised, those of us watching this case, that EPA was going to lose. But the court invoked this new doctrine called a major question doctrine, which basically interferes with the way Congress delegates authority to agencies like EPA, to deal with emerging environmental problems, even crises like the climate crisis. And the court has really now adopted a rule of interpreting the scope of agency authority that's going to make it harder for agencies like EPA, like the Fish and Wildlife Service, to interpret their statutory authorities in ways that address these emerging environmental problems. So that case stands out as the most dramatic court decision from last term.

Over the last three presidential terms, the precise scope of WOTUS (Waters of the United States), protected under the Clean Water Act of 1972, has been fiercely debated. (Photo: Tim Lumley, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, looking ahead to 2023, what upcoming decisions are you keeping an eye on?

PARENTEAU: We have these climate liability lawsuits against the fossil fuel industry, all of those are at an early stage. And they're all questions of where should these cases be heard: in state court, or federal court? Oil companies would prefer to be in federal court, where they think they're going to get a better outcome. But all of those cases, and there were like five different courts of appeals decisions, have sent those cases, back to the state courts to be heard. And now we're waiting to see whether the Supreme Court will accept review, in at least three of these climate liability cases, led by the City and County of Boulder, Colorado, but also the city of Baltimore. And of course, there was the argument in the big Clean Water Act case, Sackett v EPA. And that case was argued last fall, it was the very first case on the docket for the Supreme Court. And so now we're waiting for a decision from the Supreme Court on the scope of the Clean Water Act. And in the meantime, of course, the Biden administration has just now adopted a new rule, interpreting the scope of the Clean Water Act. But that's very much in doubt, until we see the Supreme Court decision. So those are some of the biggies carrying over into the new year.

CURWOOD: And one of these cases involves climate racketeering, Pat?

Puerto Rican communities, devastated by Hurricane Maria in 2017, have brought a lawsuit against fossil fuel companies under the Racketeer Influenced Corrupt Organizations (RICO) act. (Photo: Kris Grogan, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

PARENTEAU: Yeah. So in this case, Puerto Rico sued not just the oil companies, but the coal companies, and plastics manufacturers under what we call RICO, the racketeering and investigation federal law, which was passed by Congress to deal with organized crime. But it's a very, very broad statute, and it has been used to address conspiracies, where companies, in this case we're talking fossil fuel companies, get together and plot to deceive the public, to deceive their customers, and also to block efforts by Congress, among others, to adopt regulations on their business activities. In the case of the oil companies, it's their carbon emissions, and so forth. So it's the first time that this law has been brought to bear on the climate issue. And there's a long way to go in this case. You know, you have to show that the companies not only worked in concert, but also used mail. And of course, internet and social media and other mechanisms. That's one of the triggers for invoking RICO. And you know, the damages that can be obtained are very significant. They include giving up profits, ill gotten gains, if you will, if you can prove this conspiracy to deceive the public. So this is definitely a lawsuit to watch. And one of the reasons I say that is because the law firm that's representing Puerto Rico has a very impressive track record of bringing cases against these major corporations under RICO and also invoking other doctrines of law to seek damages from these corporations. So you've got a battle of giants, you've got a really big powerful law firm up against, of course, the powerful law firms representing the fossil fuel industry. So the Puerto Rico case is a big one.

CURWOOD: So, the National Environmental Policy Act and the Endangered Species Act took a lot of hits during the Trump administration, the scaling back on how those laws should be enforced. What if anything, do you think is likely to happen with these in the upcoming year?

PARENTEAU: Well, that's very true. There's a list of rules that were adopted under the Trump administration, Endangered Species Act, National Environmental Policy Act, Clean Water Act, and so forth. And the truth is that the Biden administration has been working to undo the rules that were adopted, but have not accomplished what's necessary. We do not have a replacement rule for the Endangered Species Act Rule the Trump administration adopted, or the NEPA rule, completely, that the Trump administration adopted. We don't have a rule now for regulating greenhouse gases from power plants as a result of the Supreme Court's West Virginia decision. We don't have any regulation of power plant emissions. So we're falling further behind on all fronts, frankly. There's certainly some good news, we haven't talked about the good news that did happen, the Inflation Reduction Act, the climate bill, for example, but frankly, in terms of everyday environmental law, we're losing ground in the United States. And we're not tackling the environmental justice component that the Biden administration is committed to doing. But you know, it's boots on the ground, when you're talking about environmental justice, it's actually getting into the communities that are suffering disproportionate impacts, with monitoring, with enforcement, with substitute sources of energy, substitute sources of manufacturing, and so on. You know, these are problems that require a much greater commitment from the federal government, not less. It certainly requires the states to step up, in many ways, and a lot of states are, in fact, stepping up. But overall, you know, going into this new year, the list of environmental problems that are staring us in the face is formidable. And if we're going to do it with incentives, instead of using regulation, then we're just talking about huge amounts of money, money measured in the billions and trillions, not just millions. So those are the kinds of things that we're looking at, going forward.

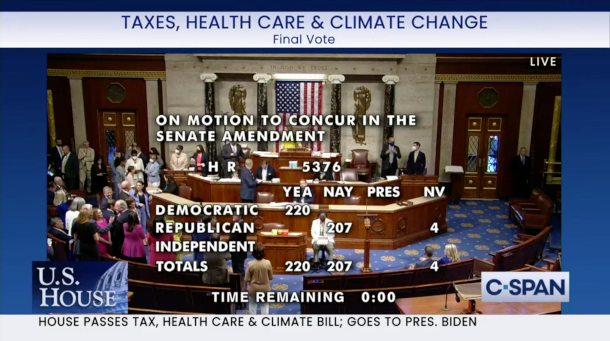

The U.S. House of Representatives passed the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 on August 12. All Democratic representatives voted yes to pass, while no Republican representatives did. (Screenshot: C-SPAN)

CURWOOD: I think it's safe to say that one of the most notable pieces of legislation passed in 2022 is the inflation Reduction Act, which in some allots close to $370 billion over the next 10 years to address the climate crisis. Many provisions that climate activists are really excited about. What should we be looking out for in 2023 when it comes to the inflation Reduction Act, do you think?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, that's a historic Act. And it does give us a shot at reducing the emissions across the economy by something like 40% by 2030. And that would be huge. So what has to happen of course now, is you've got to turn all of those words of the statute into rules and actions and investments very fast. And the first rule that rolled out actually came from the Treasury Department. The Treasury Department had to issue a rule on how the money to individual consumers for things like electric vehicles, both new and used, heat pumps, solar panels, and a variety of green energy technologies. How do you get those down to the level of individual households? And of course, how do you build larger systems, commercial scale systems as well? And here's how tricky this all becomes.

Pat Parenteau is emeritus professor of law at Vermont Law School and formerly served as EPA Regional Counsel. (Photo: Courtesy of Vermont Law School)

As a condition of getting the Inflation Reduction Act passed, and getting Senator Manchin's support, the Act requires a Made in America provision. So in order for you to qualify for the $7,500 tax credit for an electric vehicle, it has to be demonstrated that the material that goes into the battery, the electric battery, the lithium ion battery, is either sourced in the United States, and we don't have much lithium mining right now, or sourced in countries with whom we have trade agreements, which doesn't include China or Russia. Those are the two major sources of lithium right now. So I'm giving an example of how fiendishly complicated these laws are and how you actually get them implemented. But the Treasury Department found a loophole and said, if you lease an electric vehicle, then the Made in America provision doesn't apply. So all of a sudden, the $7,500 credit can be available to people who at least are willing to lease a vehicle. So that's one tiny little example. And you're right, it's $370 billion dollars worth of money, which is real money when it comes to a clean energy investment. And it is very good news for the new year.

CURWOOD: Pat Parenteau is an emeritus professor of law at the Vermont Law School. Pat, thanks so much for your time today.

PARENTEAU: Pleasure, Steve. Always.

Related links:

- Pat Parenteau’s article in The Conversation | The Supreme Court Curtails EPA’s Carbon Regulating Powers

- Supreme Court of the United States | “Sackett vs. EPA Oral Argument Transcript: 10/03/2022”

- The Guardian | “Big Oil Is Behind Conspiracy to Deceive Public, First Climate Racketeering Lawsuit Says”

- Read the Inflation Reduction Act

[MUSIC: Soulive, “Doin’ Something” on Doin” Something, Blue Note Records]

DOERING: Coming up – We remember some key environmental figures we lost in 2022. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Soulive, “Doin’ Something” on Doin” Something, Blue Note Records]

Auld Lang Syne

Joe Hazelwood was Captain of the Exxon Valdez, a supertanker that spilled 11 million gallons of oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound in 1989. (Photo: NOAA, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

And I’m Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: And with me on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia is journalist Peter Dykstra to take a look back at some of the people that we lost in the year 2022. Hi there, Peter. How you doing?

[MUSIC: Richard Freeman, “Auld Lang Syne Jazz” on Jazzy Christmas, Relax Café Music]

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. There's a real eclectic mix of people who had an impact on the environment. Not always a good impact. So on that note, we'll start with Captain Joe Hazelwood. Up until March 1989, he was highly paid, top of his profession, supertanker skipper. And after a night of what the captain later admitted was heavy drinking, he retired to his cabin, leaving a third mate to guide the 986-foot Exxon Valdez out of port and on its way to an 11 million gallon disaster. Captain Hazelwood died in July.

CURWOOD: Yeah. And you know, you can still go up there to those waters in Alaska and find little balls of oil. Not all of it has yet been collected. And I don't think all the people in that disaster were paid.

DYKSTRA: Not yet. Some of them also died before the payment from Exxon made its way through the legal system. But we move on to the dismal science of economics. In 2022, we lost two of the shining lights of dismal science on the environment. Hazel Henderson passed away in May. She popularized the phrase, think globally, act locally. And she advocated redefining what a strong economy is, as embracing good health, quality of life. And not just what your bank balance and your stock portfolio said. Herman Daly died in October. He co-developed the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare. That too, was an effort to supplant the Gross Domestic Product, the kind of cold-hearted way of measuring wealth by dollars only, with health, happiness, and ethics be damned.

CURWOOD: Yeah, and both of these really made the point that, you know, traditional economics sees a tree having value only when it's cut down and made into boards. But then of course, trees do much more than that for us.

DYKSTRA: A Nobel laureate died this past year. Pat Michaels is the most ironic Nobel Peace Prize laureate ever. He shared the 2007 prize with Al Gore and 1500 of his fellow scientists on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, despite his status as the go-to scientist for climate change deniers. He actually didn't like the term "denier." He said that climate change was real, but that its impacts were way overstated by his fellow scientists. He did fill the denier role very nicely for groups like the Western Fuels Association. That's a coal industry trade group based in Wyoming. Pat Michaels died in July.

CURWOOD: Boy, Peter, you have to wonder what he'd say about the recent wacky weather we've had, with all these storms and floods and fires and such.

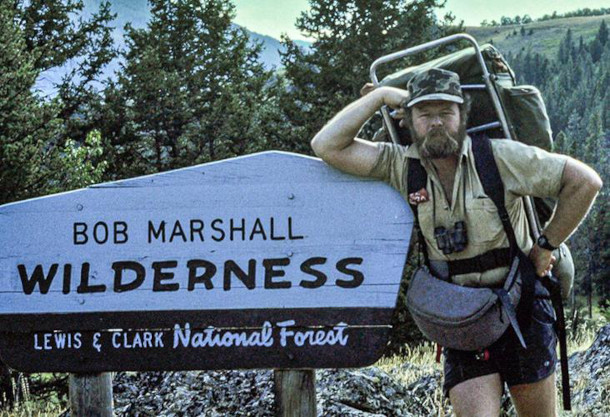

David Foreman co-founded Earth First!, a radical environmental advocacy group, in 1980. He also later founded the Rewilding Institute. (Photo: Courtesy of Nancy Morton)

DYKSTRA: He'd say it was just wacky weather. Dave Foreman is an opposite number for Pat Michaels. Disillusioned by his job lobbying for The Wilderness Society, he was inspired by Edward Abbey, the novelist, who wrote The Monkey Wrench Gang. Foreman and Mike Roselle founded Earth First! in 1980. They were the consummate eco-hellraisers. In later years, Foreman founded the Rewilding Institute, advocating for turning developed land back to nature. Dave Foreman died in September.

CURWOOD: And will be missed.

DYKSTRA: And in June, journalist Dom Phillips and indigenous expert Bruno Pereira were murdered deep in the Amazon rainforest. Brazilian authorities arrested three men a month later. They of course are part of what will later in the year be the Global Witness List, sometimes numbering in the hundreds of environmental activists murdered in developing nations like Brazil and Honduras.

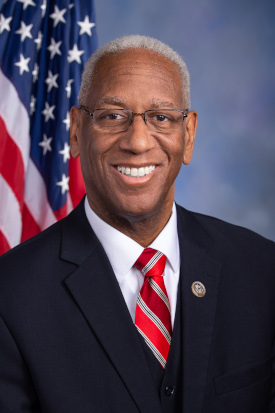

U.S. Rep. A. Donald McEachin (D-VA) scored 96% on the League of Conservation Voters environmental scorecard in 2021. (Photo: U.S. House Office of Photography, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Yeah, it's a very risky business in those places.

DYKSTRA: There are two members of Congress who were respectively stalwarts for and against environmental regulation, who died in 2022. A. Donald McEachin from the low-lying area around Norfolk, Virginia, died in November shortly after winning his fourth term. He was an ardent environmentalist who focused on climate change and environmental justice. He represented a chunk of the Hampton Roads region around Norfolk, Virginia, a region that's already coping with flooding from sea level rise. McEachin's score, in the most recent year available was 96% from the League of Conservation Voters. His opposite number actually scored 36%, which is positively angelic for a Republican. This guy was, of course, Don Young, the very gruff Alaskan, longest serving Republican ever in the House of Representatives. He, of course, was a big advocate for fossil fuels, and the income that oil and gas drilling brought to his home state of Alaska.

U.S. Congressman Don Young (R-AK) advocated for the economic benefits of oil and gas drilling in his home state of Alaska. (Photo: U.S. House Office of Photography, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Yeah, he served what, 49 years in the US house?

DYKSTRA: As the only Alaska congressman. And we'll turn to Lucia Small, who was a documentarian who had a lot to say about feminism and the environment.

CURWOOD: And she said it on this show as well. She was one of the people that helped us get Living on Earth started way back in the day. Living on Earth also lost a major supporter and board member Henry Rosovsky, who at one time was an acting president of Harvard and a major economics professor and Dean there.

DYKSTRA: And here's one that's near and dear to my heart. A good friend of mine, a CNN colleague, Gary Strieker. He was a disenchanted banker in Nairobi whose epic midlife epiphany found him learning how to shoot and edit video about the plundering of a beautiful continent. His work and his audience went global on CNN for the better part of two decades.

We are deeply saddened to learn of the recent passing of Lucia Small (1963-2022). We join with the rest of the Boston film community in recognizing her enormous accomplishments and celebrating her life. Her presence will be missed but we will always remember her tenacious spirit. pic.twitter.com/SsVK7a0GXB

— Documentary Educational Resources (@DocuEd) November 24, 2022

CURWOOD: Just beautiful pictures of not just animals, but the mountains and people.

DYKSTRA: And last but not least on my list is the passing of a fictional character, who won't even be born for another 200 years. I refer, of course, to Lieutenant Nyota Uhura, aka actress Nichelle Nichols. She graced the bridge of the Starship Enterprise for the three year run of the original Star Trek series, as the show ascended to cult and rerun status. Nichols then became an evangelist and recruiter for science, space, and NASA, particularly for women and people of color. NASA Administrator Charles Bolden, the first Black Administrator of NASA, and at least five space shuttle astronauts have credited Nichelle Nichols with helping to launch their careers. She died in July.

CURWOOD: And famously Martin Luther King, Jr. approached Nichols when she was thinking of not signing up for another season of the show saying no, no, no, you can't quit because you are such a trailblazer for people of color in this country. And he was absolutely right.

DYKSTRA: He was indeed. Live long and prosper.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is a journalist living in Atlanta, Georgia, and we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. We'll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories and these people on the Living on Earth webpage. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- The New York Times | “Joseph Hazelwood, Captain of the Exxon Valdez, Is Dead at 75”

- The New York Times | “Hazel Henderson, Groundbreaking Environmentalist, Dies at 89”

- The New York Times | “Herman Daly, 84, Who Challenged the Economic Gospel of Growth, Dies”

- The New York Times | “Patrick J. Michaels, Vocal Outlier on Climate Change, Dies at 72”

- The New York Times | “David Foreman, Hard-Line Environmentalist, Dies at 75”

- The Washington Post | “The Killing of Dom and Bruno”

- Politico | “Virginia Rep. Donald McEachin Dies At 61”

- NPR | “Don Young, Alaska’s Longest Serving Congressman, Dies At 88”

- The Boston Globe | “Lucia Small, Who Brought Women’s’ And Girls’ Voices To Forefront In Documentaries, Dies At 59”

- NPR | “Nichelle Nichols, Lt. Uhura On ‘Star Trek,’ Dies At 89”

[MUSIC: Alexander Courage, Gerald Fried, Bob Harlan “Star Trek – The Motion Picture: Main Title” on Boston Pops Orchestra: John Williams, UMG Recordings]

Midnight in the Everglades

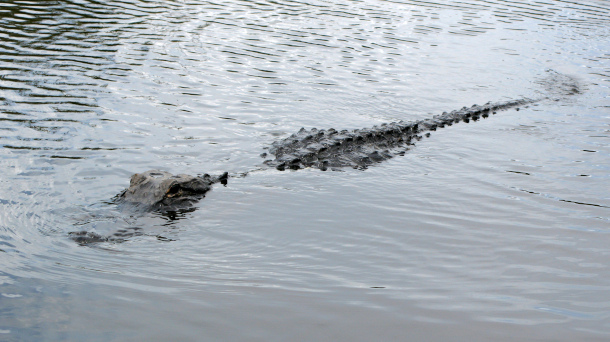

An alligator in Everglades National Park. (Photo: Sheila Sund, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: Alligators have such gaping jaws you might wonder what they eat. For one group of researchers looking into this the answers so far point to snails and amphibians like the giant salamanders known as amphiumas rather than fish or hapless mamals that walk too close to swampy waters. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman spent a night in Florida’s Everglades with a team investigating this and shares his story with us.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Distill,” Darby, Blue Dot Sessions 2021]

LYMAN: We ply the darkness in a noisy airboat, my friend Brady in the pilot’s seat, spotlighting for alligators. The flat hulled craft is made for this environment, and we move easily through thick patches of four-foot-tall sawgrass and shallow water that ranges in depth from a few inches to a few feet. The breeze from the moving boat makes the 70-degree early evening air feel cooler than it actually is.

Brady is a graduate student, studying alligator diets in Everglades National Park for his Ph.D. dissertation. He has spent the past few years catching gators and pumping their stomachs to analyze what they are feeding on — research that could prove important in helping to conserve the iconic reptiles.

"There's one up ahead!" Brady shouts over the roar of the engine. Don, his undergraduate assistant, stands at the bow of the boat holding a gator noose, which consists of a long aluminum pole with a wire noose attached to about 30 feet of rope.

The reptile's eyes glow orange in the beam of the spotlight as it floats motionless in the water ahead. As we get closer it begins to swim away along the surface. Brady explains that alligators spook easily in daylight, quickly diving out of sight, but for some reason at night they don't, making them easier to capture, which is why gator researchers often work the graveyard shift.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Flashing Runner,” Resolute, Blue Dot Sessions 2017]

LYMAN: Don steadies himself as Brady maneuvers the boat closer to the swimming animal. He reaches out with the noose and tries to slip the loop of wire over the gator's head, but misses.

"Get him!" Brady barks.

"I'm trying!" Don shoots back.

When we get close, Don tries again, but again he misses.

“Just get it on him!” Brady yells.

On his third attempt Don lassoes the gator, which dives under water with a splash of its thick, powerful tail.

It pulls on the line, occasionally surfacing near the boat, thrashing wildly.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Flashing Runner,” Resolute, Blue Dot Sessions 2017]

LYMAN: After about 10 minutes the gator begins to tire, and Don slowly pulls the line in. Brady cuts the engine, comes down onto the deck, and lies down on his stomach to be in position to grab the gator, but quickly decides he’s too vulnerable.

“Let me get on my elbows,” he says. “I can’t go anywhere if the gator tries to get me.”

A twelve-foot alligator pokes its head above the surface of the water. (Photo: djmcaleese, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Brady asks me to duck tape the gator’s jaws shut, so I join him on the deck with a roll of duct tape, nervously crouching on my knees, my heart pounding. Don maneuvers the line so the gator's head is above water and tight against the bow. Brady grabs the gator's jaws and holds them shut while I duct tape around the animal’s snout as fast as I can, with Brady yelling "Hustle! Hustle! Hustle!"

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Flashing Runner,” Resolute, Blue Dot Sessions 2017]

LYMAN: When the duct taping is through, Brady releases his grip, Don lets up on the line, and the gator disappears beneath the surface in an explosion of water.

After several minutes Don once again pulls the exhausted animal toward the boat. He and Brady step off the edge of the bow into the knee-deep water and wrestle the big black reptile onto the deck. Don lies on top of the gator with his hand over its eyes to keep it still while Brady duct tapes the animal’s feet together behind its back so it can’t move around.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Plaster Combo,” Darby, Blue Dot Sessions 2021]

To pump the gator’s stomach, it has to be filled with water, which is done using a submersible pump attached to a section of garden hose. Brady removes the duct tape from the gator’s mouth, then gently taps the reptile on the snout with a section of PVC piping. The gator opens its mouth wide and lets out an angry hiss.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Plaster Combo,” Darby, Blue Dot Sessions 2021]

Brady places the pipe lengthwise in the gator’s mouth, which causes it to clamp down hard on the PVC piping. He then wraps duct tape around the gator’s mouth again, so the plastic pipe won’t fall out.

The pump is placed in the water, the animal is rolled onto its back, and the end of the hose is lubricated and gently inserted down the alligator’s throat through the PVC pipe. Its stomach quickly fills with water when the pump is turned on.

I press down on the reptile’s distended stomach with both hands, like I’m performing CPR, causing the gator to regurgitate its stomach contents into a bucket, which we collect for processing back at the lab. We repeat this routine several times until nothing but water comes out.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Plaster Combo,” Darby, Blue Dot Sessions 2021]

LYMAN: Brady told us one time he was pumping the stomach of a big gator and a live three-foot-long amphiuma — a large, aquatic eel-like salamander — rocketed out of the gator’s mouth and latched onto Brady’s arm, giving him a painful bite and scaring him half to death.

Fortunately, the gator we captured contained only a few clumps of scales from a water snake it had eaten.

“That’s a pretty Spartan diet,” Brady comments.

After measuring and tagging the animal, we untape its legs, and the 10-foot reptile calmly clambers over the side of the airboat into the water, and slowly swims away along the surface into the darkness.

Over the next several hours we catch a few more gators, and repeat the stomach pumping routine.

Don Lyman (left), Seth Lambiase (center) and Brady Barr (right) grab hold of an alligator on their airboat in Everglades National Park in November 1996. (Photo: Don Cramps, courtesy of Don Lyman)

Brady said that prior to his study it was thought alligators in south Florida ate mostly fish, but he had discovered that larger gators fed predominantly on snakes, amphiumas, and surprisingly, apple snails. In fact, snails were the major prey item for sub-adult alligators. Brady had found that big gators would occasionally feed on wading birds and mammals too. His research helped to analyze the complex interconnected food web that makes up alligators’ diets.

After tagging the last gator, we release it back into the water, then sit for a bit contemplating the night’s events.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Distill,” Darby, Blue Dot Sessions 2021]

LYMAN: The adrenalin is still pumping as we excitedly recount our adventures.

“Did you see Don jump when that big gator attacked the airboat right under his feet?”

Brady says. Excited banter soon gives way to quiet reflection.

“It’s beautiful out here,” I say.

“It sure is,” Brady replies.

Moonlight illuminates our surroundings, and a gentle breeze blows in from the Gulf of Mexico, stirring the sawgrass. A red light blinks from the top of a radio tower in the distance, and lightning briefly flashes in small patches here and there on the horizon. Solitude envelops us.

[OWL SOUNDS]

DOERING: That’s Living on Earth’s Don Lyman.

Related links:

- Learn more about Everglades National Park

- Don Lyman’s Twitter

- Learn more about Dr. Brady Barr

[MUSIC: JJ Grey & Mofro, J.J. Grey, “Fireflies” on Lochloosa, Fog City Records]

CURWOOD: To get the stories behind the stories on Living on Earth as well as special updates please sign up for the Living on Earth newsletter. Every week you’ll find out about upcoming events and get a look at show highlights, and exclusive content. Just navigate to the Living on Earth website loe.org and click on the newsletter link at the top of the page. That’s loe.org.

[MUSIC: JJ Grey & Mofro, J.J. Grey, “Fireflies” on Lochloosa, Fog City Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – The accidental ecosystems that cities provide for wildlife. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Lettuce “Blaze” on Resonate, Round Hill Records]

The Accidental Ecosystem

Peter Alagona’s 2022 book “The Accidental Ecosystem: People and Wildlife in American Cities.” (Photo: Courtesy of University of California Press)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

Gray squirrels are common in most US cities, but you might be surprised to learn they’re a relatively recent arrival, moving to the urban jungle in the mid 19th century. In fact, for a long time cities were devoid of most wildlife we take for granted today. Even pigeons, crows, and raccoons, were scarce. Eventually the wildlife we now consider common found homes among us. In his 2022 book “The Accidental Ecosystem: People and Wildlife in American Cities,” environmental historian Peter Alagona explores that transformation. Peter is a professor of Environmental Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Welcome to Living on Earth, Peter!

DOERING: So cities without squirrels... Really? I mean, come on! Take us back to the time when wildlife were absent from our cities. Why were they like that?

ALAGONA: You know, it's such a funny question, because when I was writing this book, and telling that story, I didn't anticipate that that would be one of the stories that would jump out to people and trigger their curiosity and cause a lot more questions to be asked. But in the months since the book has come out, I've got a lot of questions about squirrels because these are such a common, well known feature of urban landscapes throughout the United States, and in fact, throughout much of the world. But it wasn't always that way. Eastern grey squirrels were native to the eastern portion of North America in forested habitats, in places like New England and into the Midwest and portions of the southeast. But over the course of a century or so, following European colonization, they were hunted for their fur and for food, they were eradicated as pests and their habitats were felled, the forests that they lived in, were felled in many areas. And so by the 18th century, Eastern grey squirrels were missing from a lot of their former range, including in cities like New York and Philadelphia, where we know them, you know, so well today. And so it wasn't until really the middle part of the 19th century that they started to come back. And that was really for two reasons: one was that people started to bring them back, people actually had been keeping them as pets, as kind of exotic pets in a way, during those years when they were so rare in that part of the country. But also, in addition to people bringing them back and reintroducing them, new habitats were created for them, cities started to plant more trees along streets, they started to construct new parks, like Central Park in the mid 19th century, and plant trees in those places that would then provide urban habitats for the species that had lived in these regions, but then was largely lost. And so this is just one example, but a really good one, of the ways in which our modern cities have attracted so much wildlife, including species that have returned and, in some cases, new species that were never really there before.

Peter Alagona is the author of “The Accidental Ecosystem: People and Wildlife in American Cities.” (Photo: Courtesy of Peter Alagona)

DOERING: So what kinds of animals do well in urban spaces?

ALAGONA: There's a way of thinking about this that's developed over about the past 20 years: we can divide animals with regard to their success or inability to live in urban areas into three categories. Now, keep in mind that this is much more nuanced, and it changes over time, but it's at least a way to start. So one group of animals that we might all recognize in relation to urban areas are the urban exploiters. Now, these are creatures that do really well in cities, and as a result, tend to occur in large numbers and in many urban areas throughout the world. And so we can all think of examples of that. These are the pigeons, the crows, the rats that you see in urban areas whether you're in North America or South America, Asia, Europe, wherever you happen to be. Then there's a group of animals that tend to be referred to as the urban adapters. Those are creatures that can do well in and around cities, but tend to require some wildland area nearby, or at least some green space in which they can seek refuge, perhaps during the day when there are a lot of people out kind of going about their business. And so this includes animals like raccoons or coyotes or foxes, some raptors or owls or large wading birds like the blue herons. And then there's a group of animals that we call the urban avoiders, which are the ones that do really poorly in cities, for any number of different reasons and are rarely seen there. Sometimes these are large bodied animals that travel long distances to forage or find mates. Or they can be creatures that are just kind of hard for people to live with, in areas where there are a lot of people living in the same place. And so this includes animals like pumas, for example. I think one of the things to recognize about this is that if you look at the exploiters, the creatures that do really well in urban areas, they tend to share a set of characteristics or qualities.

DOERING: And what are those characteristics?

Many may think of gray squirrels as ubiquitous to the average American city, but they only began to settle in urban environments in the mid-19th century. (Photo: Adam Jones, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

ALAGONA: They tend to be social. So they are relatively comfortable around large groups of their own kind, large numbers of their own species. They tend to have cultures where they learn things and experiment and then pass on their knowledge to their young. They tend to be relatively flexible, so they can live in a lot of different kinds of habitats. They tend to have relatively large brains, maybe, in relation to other animals that are closely related to them. That's an area of ongoing research. And, crucially, they tend to be omnivores, which means that they can harvest a wide variety of resources as food that they might find in urban areas. But you know what the funny thing is, Jenni? If you think about putting all of these qualities together: social, cultural, omnivores, relatively large brains. That sounds to me a lot like people. And so one of the things that we can notice about urban exploiters, creatures that tend to do really well in urban environments, is that they have some qualities that are something like the qualities that we have.

DOERING: Wow, that's fascinating. I would never have thought of that before.

ALAGONA: But you know, if you think about exploiters, one of the most common exploiters, of course, are rats. And rats are also used as model organisms for biomedical research. There are reasons for that, so they're easy to breed, they're easy to keep, there's relatively little controversy around using them for experimentation. But also, because they're enough like people that we can learn something from studying them. And I know that the listeners in your audience don't necessarily want to hear that they're like rats, but we do have things in common with creatures with which we share our habitats.

DOERING: Yeah, we're not really that different from these other critters that we live among. So Peter, of course, it isn't always easy living with wild animals nearby. How much of a real threat do predators like bears, pumas and coyotes pose to urbanites? And what are some examples of ways to prevent this wildlife human conflict?

Animals that thrive in cities tend to be social, intelligent, and omnivorous – much like human beings. (Photo: Pete Beard, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

ALAGONA: I think that our views of the risks that are out there and the conflicts that occur are very much conditioned by the media. Unfortunately, when we get our information from the media, we get a lot of different kinds of signals and, oftentimes, conflicts are what's emphasized over coexistence. So if there's a particular incident that happens with a coyote, for example, or with a fox or a raccoon, we hear about it, we don't hear about all the days and all the times that nothing happens at all, and we go about living together in our communities. And so as a result, the concerns over living with urban predators are often believed to be much greater than they are, in general, these animals are very predictable, they tend to not be aggressive toward people, and they tend to live among us, sometimes for a long time without us even really knowing it. You know, there are some other potential issues that can arise. Sometimes people get gophers in their garden or other sorts of things. And the best thing to do in that case, is to, oftentimes, to not focus quite so much on eradicating the animal, which is, oftentimes, the approach of pest control. But really thinking about the kind of habitat you're creating, in and around your apartment, in and around your home. And whether or not the habitat you're creating is drawing in the kinds of animals that you want to live in close contact with. If there are ways to modify the habitat a little bit to discourage some of the creatures you want to see less of and encourage some of the ones you want to see more of: the plants, we put it outside our homes, the gardens we construct, the ways that we move through our neighborhoods, whether we speed down our streets in our neighborhoods. All of these things are subtly altering the urban habitat in ways that inventive, in some cases ingenius, urban animals are able to take advantage of. The reason I called this book "The Accidental Ecosystem" is that part of my argument is that we ended up getting a lot of wildlife in urban areas unintentionally, as a result of decisions that people often made decades ago and for other reasons. People started planting trees in cities in the 19th century, not because they were trying to attract squirrels. But because they thought it was going to be better for human health and well being to have cities with trees, to have cities with shade.

DOERING: Which is also true.

Coyotes can be drawn to urban areas, but intentional city design can help limit human-wildlife conflict. (Photo: Connar L’Ecuyer, National Park Service, public domain)

ALAGONA: Which is also true. And so it seems to me that if we want to move forward and think about moving from an 'accidental ecosystem', to a more intentional urban ecosystem, where we're really thinking through the kinds of creatures we want to surround ourselves with the kinds of habitats we want to create, the kinds of ways that we can foster thriving and coexistence, not just for wildlife, but also for people, then maybe it pays to think about these places as multi-species communities, to think about being more intentional in the ways that we construct urban habitats, thinking forward about the kinds of creatures that are going to be around us as a result of that. And then also thinking about how that relates to human health and well-being. If we do that, how will that help us to craft better cities, better urban areas in the future?

DOERING: Yeah. Speaking of that, how do you envision wildlife in the cities of the future? What might that look like in the US in 100 years time?

People started planting trees in cities and constructing urban parks for human health, inadvertently creating habitat for other animals. (Photo: Marc, Metrotrekker, CC BY-SA 4.0)

ALAGONA: I don't know what that's going to look like, but here's what I will say. Just this move from this idea that cities are for people and when wild creatures show up there, it's either something that's bizarre, or something that's funny or a spectacle or it's a problem that needs to be dealt with, through pest control, through eradication, moving from that view, to the view that cities are habitats, they're shared habitats, and they're multi-species communities, that alone is a move that then shifts how we think about everything we do in those spaces. So, for example, if we're thinking about transportation, and we want to build a transportation system for the future, well, that has to accommodate a growing population, it has to accommodate changing needs, changing distribution of people on the landscape, it's definitely going to need to accommodate changing technologies as we move, for example, to driverless cars and things like this. But also, how can it better accommodate wild creatures? We know that roads are the source both of isolating populations of wildlife, animals that can't cross roads to travel to other patches of habitat. We also know that roads are sites where a lot of animals die through roadkill. How can we reduce that? Well, we know for example, that roadkill does not happen randomly. It tends to happen in particular areas where wildlife, wild creatures are crossing from one patch of habitat to another. And so if we just think about that, then suddenly we can say, well, wait a minute, maybe those are areas where we should increase lighting, where we should reduce speed, where we should provide signs, where we should maybe do law enforcement as well, education, because when people have auto collisions with wild animals, it's a danger to them as well as the creatures. It's also a threat to private property. And so focusing on those sorts of questions, I think, in a more focused and enduring way over time, I think will enable us to rethink cities in ways that helps people live with creatures, that reduces the risks of living with them, and that enables us to live side by side in cities that will inevitably look very different 100 years from now than they do today.

DOERING: Yeah. Before you go, Peter, are there any species that you're really happy to have around in your city?

ALAGONA: Absolutely, yeah. I mean, I'm happy to have every creature that I run into, every wild creature is a source of fascination to me. But if I had to name one, I would say this. A few years ago, I was living in a home just about a mile and a half from from where I'm living now. And one year we had a pair of great horned owls that nested in a Canary Island date palm tree, and exotic tree right across the street. They laid three eggs, gave birth to three chicks, two of them survived and fledged. And over the course of this several month process, we had these two amazing great horned owls living across the street from us, flying around our neighborhood from tree to tree, hooting in the evenings, hunting, we found lots of parts of animals, rats and other animals, maybe creatures that we didn't want to see around as much as the owls.

Great Horned Owls are one of the most common owls in North America and equally at home in forests and cities (Photo: Tim Lumley, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Yeah.

ALAGONA: And so the owls were performing this incredible service for us. We got to see the chicks fledge and fly away. And not only that, but through this process, I got to meet neighbors, community members who I'd never had an opportunity to meet before, because we were all out there in the evenings, watching these owls and paying attention to them and following them and their chicks. And it was just a wonderful community experience. And so I look back on that as a very formative moment when I realized that, you know, coexistence with wildlife, it's not just about people and other animals. It's about people and people. And there are cases in which living with wildlife can bring us closer to our human neighbors as well.

DOERING: Peter Alagona is a Professor of Environmental Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara and the author of "The Accidental Ecosystem: People and Wildlife in American Cities". Thank you so much, Peter.

ALAGONA: Thank you, Jenni.

Related links:

- Find Peter Alagona’s website here

- Find the book “The Accidental Ecosystem” (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Frank Sinatra, “Theme From New York, New York – 2008 Remastered” on Nothing But The Best (Remastered), Frank Sinatra Enterprise, LLC]

Baby Oysters Listen for Safety

It appears that oyster larvae are attracted to the sounds of a healthy reef. (Photo: Petras Gagilas, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Not everyone likes them, but for aficionados there’s nothing quite as tasty as a freshly shucked oyster. And when it comes to managing tidal surges at the ocean’s edge, oyster reefs make a big difference. These reefs also create habitat for other species and as filter feeders oysters keep waters clear of excess algae and nutrients that might otherwise degrade water quality. Many oyster species including the Australian flat oyster are under threat. So, some scientists in Australia are looking into how baby oysters, otherwise known as spat, find an appropriate place to set up shop. And it turns out sound may be key. Living on Earth's Sophia Pandelidis has more.

[OCEAN SOUNDS]

PANDELIDIS: For a baby Australian flat oyster, the world beneath the waves can be a scary place.

When it first leaves the safety of its parent’s shell, an oyster larva is only around 170 microns long—that’s about as thick as two sheets of paper.

And if it hopes to be one of the lucky survivors out of millions of siblings, it better find a place to settle–fast.

Scientists are uncertain about how exactly these little larvae choose which way to go.

The “sizzling bacon” sound of snapping shrimp dominates the underwater soundscape of a thriving reef. (Photo: budak, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

But it’s possible that oysters use sound to navigate.

Oysters don’t have ears, but they can still interpret and react to sound by sensing with their bodies the way that sound waves rattle particles as they move through water.

[sounds of shipping motors (Source: Freesound, Mrthenoronha)]

PANDELIDIS: It is well-known that anthropogenic noise pollution can be disruptive to marine life. The sounds of shipping motors, offshore construction,

[offshore construction (Source: Freesound, Mrthenoronha)]

PANDELIDIS: And military SONAR.

[Sonar (Source: FreeSound, Breviceps)]

PANDELIDIS: Can be disorienting and sometimes lethal for underwater organisms.

Fish also make a wide variety of sounds, ranging from “purring” to “grunting.” (Photo: Stefan David, CamperCo.de, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

In fact, oysters have been shown to slow their feeding and growth rates–and even clamp their valves shut– when bombarded with these noises.

But oyster larvae have also been known to swim impressive distances towards a pleasing sound.

So, researchers at the University of Adelaide in Australia tried to find out if sound might even be a key to oyster restoration.

[snapping shrimp sound (Source: Dr. Dominic McAfee, University of Adelaide)]

PANDELIDIS: They set up a soundscape imitating a healthy reef– an ideal spot for an oyster to settle down– and played it on carefully positioned underwater speakers.

Sea urchins scrape algae off rocks with their teeth, adding yet another sound to the reef environment. (Photo: Diane Graham, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

[crackling continues]

PANDELIDIS: Snapping shrimp, which hide in the nooks and crannies of reefs, dominate this underwater orchestra.

[snapping shrimp in the clear]

PANDELIDIS: They create air bubbles that pop by snapping their claws together at roughly 60 miles per hour, making them one of the fastest moving creatures in the animal kingdom.

And while researchers say the shrimp take first chair in the underwater orchestra, other creatures add richness to the symphony.

[Fish sounds (Source: Research Paper: The sound of recovery: coral reef restoration success is detectable in the soundscape, from the Journal of Ecology, also given explicit permission and additional audio files from Dr. Timothy Lamont from the University of Exeter, lead researcher on the paper)]

PANDELIDIS: Fish that purr, grunt, whoop, and even honk make up the brass section.

Dominic McAfee, the lead researcher in the restoration project, holds one of the underwater speakers his team developed. (Photo: Dominic McAfee)

And grazing urchins, which scrape algae off rocks with their teeth, bring in the percussion.

[grazing urchins sound (Source: “Sea Urchin Grazing” on Vimeo, credit to Craig A Radford, University of Auckland, from whom I also got explicit permission)]

PANDELIDIS: Dr. Dominic McAfee, the lead researcher in the project, says his team even added non-animal elements

[Thunder sound (Source: Freesound, Simon Spiers)]

PANDELIDIS: Like lightning strikes and crashing waves to flesh out the acoustics here. And it’s worked.

McAfee and his team found that oyster recruitment increased significantly at sites near the reef-imitating speakers.

They saw 17,000 more larvae settled per square meter on boulders they placed near the speakers, as compared to settlement areas without the presence of added sound.

Many oyster species worldwide have been decimated by human activity.

And the Australian flat oysters were harvested to the point of near extinction over the last few centuries.

That’s bad news for water quality—oysters are crucial for filtering water in aquatic ecosystems.

Oysters can also form reefs that can act as natural barriers, protecting shorelines from severe storms.

So people have a vested interest in restoring a healthy oyster population.

Dr. McAfee’s students build the speaker designed to attract oyster larvae to restoration sites. (Photo: Dominic McAfee)

In Australia national restoration efforts began in 2015, and the Adelaide researchers hope to include soundscapes in future restoration work.

[continue snapping shrimp, fish sounds]

PANDELIDIS: They are optimistic that an underwater symphony will be able to attract other species as well to improve their populations and create healthy reefs.

For Living on Earth, I’m Sophia Pandelidis.

Related links:

- Journal of Applied Ecology | “Soundscape Enrichment Enhances Recruitment and Habitat Building on New Oyster Reef Restorations”

- Journal of Applied Ecology | “The Sound of Recovery: Coral Reef Restoration Success Is Detectable in the Soundscape”

[MUSIC: Joey Alexander “Draw Me Nearer” on Eclipse, Motema Music LLC]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Fern Al-ling, Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. We bid farewell this week to Chloe Chen, Ashley Soebroto and Kharishar Kahfi. Thanks for all your enthusiasm and hard work!

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth