The Power of Black History

Air Date: Week of February 24, 2023

The Slavery Museum at the Whitney Plantation, the only former plantation site in Louisiana with an exclusive focus on slavery. (Photo: Cheburashka007, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The burial of a nine-year-old enslaved girl on a plantation in Louisiana may halt construction of a new petrochemical plant on that land in the state’s “Cancer Alley.” Many descendants of enslaved people in the region already live with health problems from exposure to industry and are looking to their ancestors to stop further expansion. Lenora Gobert, a genealogist for the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, joined Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

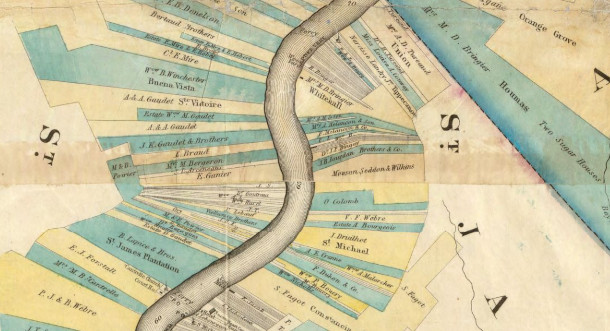

For more than 100 years before emancipation, enslaved people of African descent were forced to work the land along the Mississippi River near the city of New Orleans. They toiled to grow sugar cane in the rich soil and enriched white land owners with their free labor. Now centuries later, the legacy of slavery persists as the descendants of enslaved people live and work in one of the most polluted regions of the country, the 85 mile stretch along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans known as Cancer Alley. African Americans in the region disproportionately live with health problems associated with exposure to the roughly 150 petrochemical plants that give the region its infamous nick name. And industry in Cancer Alley is still expanding. The Taiwanese company, Formosa, is pushing for a new 9.4 billion dollar petrochemical plant to be built on a piece of land known as the Buena Vista Plantation. But genealogists have uncovered evidence that enslaved people were buried on that land. And since several laws prohibit building on historical sites activists are hoping that they can stop the expanding petrochemical industry by telling the stories of enslaved people in the region. In honor of Black History Month we would like to share some of those stories as well. Lenora Gobert is a genealogist for the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, an activist group against Louisiana’s expanding petrochemical industry. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: Please tell me how your genealogical research connects to resisting heavy industry?

A petrochemical plant owned by Formosa. (Photo: Formulanone, Flickr, CC BY SA 2.0)

GOBERT: Well, it's really interesting. And the way I like to characterize it is, if you're familiar with some of the culture of Louisiana, there's something called a second line, which traditionally has been the line of people that have followed the casket and the musicians taking somebody to a burial site. And that's how I look at my work. There are people who have been fighting the fight against the petrochemical companies. And this includes the community organizations as well as lawyers and other environmental organizations working along with them. I am coming behind them to help document the claims that are being made about ancestors being buried on the plantations and therefore being threatened by the expansion of petrochemical companies. And people who are from the area have always said that there are grave sites there, there are people buried there. So this started sparking the interest of other community members and people working at the Bucket Brigade, to ask me to start looking into it and see what I could find. And yes, in fact, from the St. James courthouse, I went to the mortgage records to find out which enslaved people had been mortgaged by Benjamin Winchester, who owned the Buena Vista plantation. And a lot of people don't know that enslaved people were mortgaged to raise money to keep the plantations running. And there was an organization, or a financial organization called the Consolidated Association of Louisiana Planters that Benjamin Winchester mortgaged his enslaved people to. So I researched it and found out that their papers are held at the Louisiana State Archives* in Baton Rouge. And I went up there, and they're just organized by month and by year in boxes. So I went there, and I had to start looking through documents from about 1820, up until about 1850, to see what transactions of Benjamin Winchester I could find. And in one of the papers, there was -- he had a few papers where he had mortgaged people and he had them listed, but in this particular one, he had the men listed together, the women and the children. And there was nine year old Rachel, and next to her name was written the word "dead" - D-E-A-D. And that sent shivers up my spine, because obviously, Benjamin Winchester had intended to mortgage her, she was on the list with everybody else, but she died before he could mortgage her. So if she died, and she's from that plantation, logic and everything that we know historically about this institution says that she is buried on Buena Vista plantation, in the enslaved peoples' burial site. So that was how the story came about. This work that I did and this document that I found, starts setting the stage for other documents to be found in additional situations, to provide this as a tool to help stop these petrochemical companies from expanding further.

CURWOOD: So what does the records tell you about Rachel, the slave aged nine, now dead, on this plantation?

GOBERT: Nothing, so far. Not many records were kept on enslaved people, as I'm sure you know. And a find like this is for me and for a lot of other genealogists extremely rare and very special, because it starts giving names and locations to people and what may have happened in their lives. But again, she was only nine years old. So I haven't revealed this yet outside of just talking to one or two people, but I have found the document where Benjamin Winchester purchased her and her mother and two brothers. So I know where she came from. I know who sold her, but I don't know anything about her life other than that, and that she died at nine years old.

Plastic nurdles created by ethane cracker plants like the ones in Cancer Alley. Plastic nurdles are the primary feedstock of plastic manufacturing. (Photo: Mark Dixon, Flickr, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Well, so, okay, where did she come from? Who sold her?

GOBERT: Well, there was an enslaver, or a slave trader, and his middle name was Fontaine, last name Rose and from Kentucky**. So that's where he brought her from. I don't know if she was born there; likely, because she was so young. I don't know where her mother came from. Her mother's name was Eve, her mother was 20 years old when she was purchased by Winchester with her children. But their history earlier than that, I don't know yet. It takes a lot of digging, if you can find anything at all.

CURWOOD: Lenora, these days if we want to mortgage something to get a loan from a bank, we mortgage property and of course, slaves were property. But we typically mortgage land and the buildings on it. To what extent does this indicate that the, as far as the banking system was concerned, slaves were worth more than the land that they were being asked to work?

GOBERT: Absolutely. The enslaved people were the most valuable asset any of these people had, they were worth more than the land or the buildings by far. And that's what fueled the industry. And that's what, I think about the northern states that benefited from slavery also, we never really talk about that. But the banks up north also dealt with the enslaved people, mortgaging them or extracting their value, if you will, to provide financing for all kinds of building projects that people had at the time.

CURWOOD: So how do you feel that uncovering stories like Rachel's help to push back against the expansion of the petrochemical industry?

GOBERT: Well, you know, these are sacred sites, actually. But the fact that this area is considered so vital to the US economy, that this heavy industry must be sited there, means that they will do pretty much anything that they need to do to overlook the fact that there are human beings who are buried all along the river, there are thousands of these burial sites. But they do not want to acknowledge them, because of course, it prevents them from building there. So the sacred sites of the enslaved people count for nothing. And this is my opinion, but I believe that to be totally true.

Sugarcane fields in front of the Marathon Garyville refinery between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana. Enslaved African Americans once toiled to grow sugarcane on plantations, and today petrochemical plants are replacing agriculture in the region. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: So the records that you found for Rachel indicate that she and her mother came from the Kentucky area. And there's a saying in the American English vernacular of being "sold down the river." How does that saying pertain in this case?

GOBERT: Well, technically, she wasn't sold down the river. But in terms of the concept, it's pretty much the same thing. Because, as you probably know, a lot of the enslaved people from the northern states, as well as the Mid-Atlantic states, were sold to the lower South. And a lot of those were to work on these sugar plantations. So conceptually, it was the same idea. Everybody's being moved south, because the labor needs are so high.

CURWOOD: What were the conditions on the sugar plantations for the slaves that worked there?

GOBERT: I'm not an expert on this, but it was brutal. And what's so interesting to me is when I first moved to New Orleans, I was really surprised how cold it can get here, how very cold it can get, in the 40s. So I started thinking about the enslaved people who were in these cabins, which, of course, are not insulated, they may have this little fireplace in the middle where they can get a little bit of heat. But their clothes were thin, I guess they had one set of clothing, they may have had one thin blanket, can you imagine how it would have been for them, even when they weren't working? It had to be horrendous for them. And they were so resilient. Most of them, many of them, lived through these conditions, to produce all of these descendants. I think everybody should revere them. They should feel proud of them. They should say their names. And the only way we can get to say their names, is looking at these documents to find out who they are.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about the money some more. How lucrative was the sugar business? How well were these white slave owners doing financially using these enslaved people?

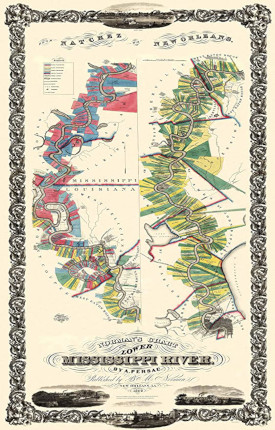

Pictured above is an 1858 Persac map of the Mississippi River in relation to plantations in Louisiana. (Photo: Courtesy of Lenora Gobert)

GOBERT: Well, from what I've read, and I know it to be true, there were more millionaires along the river than anyplace else in the United States when these plantations were operating. It was so lucrative, this sugar industry, it was the fuel that ran the economy for the United States and the globe. I mean, England was so complicit in this. I'm hesitating right here, because it was so big. People don't think about how big this industry was globally, and that it all came from the labor of these enslaved people. But these people were extremely rich, extremely rich.

CURWOOD: Well, sugar is addictive.

GOBERT: [LAUGHS] Yes.

CURWOOD: And I think once the Europeans understood about sugar cane, they were able to sell as much as they could make.

GOBERT: Well, that's right. And it's so interesting, again, I'm stepping a bit outside my area of expertise, but I'm thinking about the LNG facilities being built in Cameron Parish now. And everybody keeps talking about how great this is for the United States, how great this is for the United States. But that liquid natural gas is going outside of the United States, and it's going to Europe, and it's going to other places. And it's not benefiting the United States. It's not benefiting us, really. That's the same type of industry and mentality that was utilized with the sugar plantations, it's the same. The plantation system is alive and well in South Louisiana.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I was gonna say, the Mississippi River was home to many slave plantations, and of course, there are many descendants of the slaves still living there. And I believe it's on the scale of 150 petrochemical plants that are today spewing out contaminants associated with cancer, but many other diseases as well. What does that tell us about systemic racism in Louisiana? For that matter, what does it say about systemic racism in the United States of America?

GOBERT: That it's been there since the peculiar institution was invented, and it's never gone away. And because it's not right in our face the way it was in the 1700s, 1800s, it feels like things have gotten better. But you're right, institutionalized slavery is more insidious, it's there. It keeps people of color from reaching their full potential, from participating in the full economy of the United States. And for some reason, people don't want to hear this. They don't want to know this. And I believe that through the work that people like me are doing, genealogists, because we document individual family stories, and we document community stories, and we let people know what has happened and what is continuing to happen, and tie those things together for them -- plantation life is still going on to this day. It's in a different form, but it's still there.

Pictured above is an 1858 map from Persac's Mississippi plantations map, that clearly shows the site of the Benjamin Winchester Buena Vista plantation at the top left. (Photo: Courtesy of Lenora Gobert)

CURWOOD: Are you suggesting that if you talk back against the chemical plant in your neighborhood, that you or your family is likely to lose their employment, their livelihood, there is no freedom for those folks?

GOBERT: I can't speak to that, specifically. The people who are in the communities and who are fighting against these plants, they would be able to tell you definitively whether or not that is true. But I do know just from talking to them that because people have jobs there, of course they're afraid to speak out. They don't want to lose their job. That's the only source of livelihood, everything else is being systematically pushed out. The communities are being pushed out, they're denuding the land of people. It's amazing. It's so systematic, and individuals fighting against huge corporations, huge money making enterprises is very, very difficult. As a lot of activists and people who have been put upon in this country know, it's very difficult.

CURWOOD: Now, what are some of the barriers that African Americans descended from slaves face in trying to trace their history?

GOBERT: Well, the main issue, I think, is the lack of documentation. A lot of families have oral histories, that when you dig into them and find documentation on the families, there are always nuggets of truth in their oral histories. They may be exaggerated, they may have changed over time. But there are nuggets of truth. And you can use those to help you find the documentation about the history of these families. But the main thing is that we've basically been written out of history, or haven't been written into history for the most part. So unless you can find the documentation, it's difficult, it's very difficult.

CURWOOD: So to what extent is documenting and respecting the resting places of enslaved people a form of reparation?

GOBERT: I'm glad you asked that question, because I think we need to start really looking outside the box in terms of what reparations are. And one of the things that is important for me as a researcher is making documents of enslaved people, and even after they were free, making those documents much more readily available to be researched. My main topic, because I'm in Louisiana, is, well, there's more than one but a huge one for me is the Catholic Church. They have so many records, because they documented the lives of enslaved people, they have so many records that I feel should be made much more easily accessible. They should be using Catholic scholars to research some of this information and bring it out so that we all know and understand what's been going on with these enslaved people. The other thing is, too, that there are so many records in courthouses, these records that I talked about earlier, the mortgage documents that have enslaved people in them, they are somewhere on the shelves, all tattered and torn, falling apart, because they're not deemed to be important. And I'm sure there are other records in these courthouses that have information on enslaved people, but they're not easily accessible. So reparations -- that to me, is opening up the archives and every place that houses documents where there are documents pertinent to enslaved people's lives, and making them easily accessible.

Lenora Gobert is a genealogist for the Louisiana Bucket Brigade. (Photo: Courtesy of Lenora Gobert)

CURWOOD: How can reconnecting with one's ancestors be empowering? What's the power you get from this?

GOBERT: I love that word "empowering" because I truly believe that a big part of the problem that we have in the United States is, with people who are of African ancestry, is a lack of self esteem. And that lack of self esteem for me, comes from them not knowing where they come from, what their people accomplished in this country. And once you started getting into those documents, you become amazed at what some of these people did after slavery and sometimes even before. So, if we knew where we came from and the contributions that our families made, not only that the resilience that they had to get through that slavery period, so that they are here today, I think they would really start having more self esteem, knowing who they are, feeling much better about themselves, and being able to move through this country in a more positive sense and more positive attitude and doing more things for themselves. That's my belief.

CURWOOD: Why is your work part of the quest to achieve environmental justice?

GOBERT: Environmental justice and racial justice and social justice, they're all intertwined. And the racial justice that we are trying to achieve, that we want to achieve, that we believe we will achieve, is to keep these communities on the land, where they have been for over 100 years. By these communities staying on this land and fighting the petrochemical industry, that is climate justice for them and everybody else because they will no longer be polluting the Mississippi River. They won't be polluting the land. They won't be polluting the air that has caused Cancer Alley to become Cancer Alley. So it's all connected.

BASCOMB: Lenora Gobert is a genealogist for the Louisiana Bucket Brigade. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

**CORRECTION: The documents of mortgaged enslaved people documented in the Consolidated Association of Louisiana Planters were found in the Louisiana State University Archives not the Louisiana State Archives.

**CORRECTION: Alexander Fontaine Rose was from Kentucky not from Virginia.

Links

Don’t miss LOE’s previous interview on cancer alley with activist Sharon Lavigne

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth