February 24, 2023

Air Date: February 24, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Chemical Concerns of the Ohio Train Disaster

View the page for this story

Eleven of the 38 train cars that came off the tracks in East Palestine, Ohio in early February contained hazardous materials including the carcinogen vinyl chloride. Crews intentionally released and burned vinyl chloride to avoid a potential explosion. Ideastream Public Media’s Abigail Bottar joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss residents’ lingering concerns about the long-term effects of the chemicals in their community. (09:09)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Journalist Peter Dykstra joins Host Bobby Bascomb this week to discuss the billions of dollars in damage to Ukraine’s environment since the Russian invasion. They also discuss the ongoing bird flu outbreak in which some 60 million chickens and turkeys have been slaughtered on hundreds of commercial farms in the U.S. For a history lesson, they dive into the 1799 Federal Timber Forestry Purchases Act, which was likely the first forest conservation measure in the U.S. (04:33)

Workers Left in the Dark About Chemical Risks

View the page for this story

Safety Data Sheets provide information about the risks of workplace chemicals. Recent research found that nearly a third of those studied contained inaccurate hazard warnings and often downplayed the risks of known carcinogens. Charlotte Brody, the Vice President of Health Initiatives for Blue Green Alliance, which co-produced the study, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss why the failure to disclose these risks undermines worker safety. (07:38)

Dolphins and People: Fishing Buddies

View the page for this story

In the coastal community of Laguna, Brazil, many net-casting artisanal fishers have an unexpected fishing partner in dolphins. Fishers who work with dolphins catch a lot more fish and now scientists have figured out what the dolphins are getting out of it. Mauricio Cantor is an Assistant Professor of biology and behavioral ecology at Oregon State University and the lead author of the study. He joins host Bobby Bascomb. (06:38)

Last Reminder! The Next Chapter of the Living on Earth Book Club

The cuddly Koala is one of the most charismatic and beloved species on Earth, but massive wildfires and habitat loss threaten their very existence. Tune in on March 2nd as we talk with award-winning Australian author Danielle Clode about her new book “Koala: A Natural History and an Uncertain Future", which takes us on a journey up into the trees to discover the remarkable physiology and ecology of koalas. ()

The Power of Black History

View the page for this story

The burial of a nine-year-old enslaved girl on a plantation in Louisiana may halt construction of a new petrochemical plant on that land in the state’s “Cancer Alley.” Many descendants of enslaved people in the region already live with health problems from exposure to industry and are looking to their ancestors to stop further expansion. Lenora Gobert, a genealogist for the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, joined Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood. (17:52)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230224 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Abigail Bottar, Charlotte Brody, Mauricio Cantor, Lenora Gobert

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb

Tracking down the history of enslaved people to fight the modern petrochemical industry in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley.

GOBERT: The fact that this area is considered so vital to the US economy, that this heavy industry must be sited there means that they will do pretty much anything that they need to do to overlook the fact that there are human beings who were buried all along the river, there are thousands of these burial sites.

BASCOMB: Also, dolphins in Brazil work with local fishermen to catch fish.

CANTOR: We estimated that they are 17 times more likely to catch any fish when the dolphins are working with them and they tend to get up to 4 times more biomass of fish. The dolphins that regularly cooperate with the artisanal fishers they are 13 percent more likely to survive to adulthood.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Chemical Concerns of the Ohio Train Disaster

EPA Administrator Michael Regan discusses air monitoring equipment with on-scene coordinators. (Source: U.S. EPA, epa.gov, public domain)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

On Friday, February 3rd a freight train operated by Norfolk Southern derailed in East Palestine, Ohio. Eleven of the 38 train cars that came off the tracks contained hazardous chemicals including vinyl chloride, a colorless gas used to make PVC pipe and classified as a known carcinogen by the EPA. Three days later, amid the fiery wreckage and remnants of the initial disaster, crews intentionally released vinyl chloride into the air to avoid a potential explosion. Local resident Jamie Cozza demanded a full toxicology report, which found it was unsafe for her to return to her home, despite early assurance from local officials that everything was fine.

COZZA: Like I told the toxicologist, he said we haven’t tested the soil yet. Then how do you know it’s safe for me to go home? That’s the problem, no one knows and they just send us back in here no instructions, everything’s back to normal. Go home. We were told go back to your homes it’s safe. My home wasn’t safe, how many other mistakes did they make.

BASCOMB: Abigail Bottar is a reporter with Idea Stream Public Media in Ohio and has been covering the Norfolk Southern train derailment for station WKSU. Welcome to Living on Earth Abigail!

BOTTAR: Hi, thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: What were some of the chemicals involved in this spill? And how dangerous are they?

A train car lies on its side at the scene of the derailment. (Photo: U.S. EPA, public domain)

BOTTAR: Absolutely. So that was a big criticism that people have that the EPA and Norfolk Southern and whatever other agencies did not come up front and say what was on the train. It wasn't until Monday that we knew that it was the vinyl chloride that was the issue. I believe Sunday night–that was when the evacuation was put in place. That was February 5th. There was a list released. The main chemicals were the vinyl chloride and butyl acrylate. Vinyl chloride is a carcinogen and long exposure to it is known to cause cancers. The butyl acrylate can cause irritation and burns to the skin and eyes and can cause headaches, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and repeated exposure can lead to permanent lung damage. So that's what we knew of by the time the evacuation started. A week later, though, the EPA finally released the full list of the contents of the train, and three more hazardous chemicals were also on the train that the public was not aware of until now. And those chemicals can also cause things like coughing, shortness of breath, dizziness, drowsiness, headaches, nausea and weakness. So those are some of the things on the trains; health officials are reaffirming that those are the side effects. But they say it's unclear what the long-term impact of exposure to these are. And it's kind of unclear, like, what the impact to the air long term will be, to the water, to the soil. So it's unclear what residents may be facing in a decade or two.

BASCOMB: What are they facing right now? What are people saying? Are there symptoms that they're experiencing?

BOTTAR: People are saying they are experiencing headaches, rashes, congestion, that the air is, like, hard to breathe, it's burning their eyes, there's still like, smells, fumes, around town. When I was on the ground last week I did not smell anything. But until today I've still been hearing people saying that it smells really bad. And the scent has been captured in people's homes. I talked to one woman who said they had to buy all new furniture because their furniture just smelled so bad. So there's just this lingering scent around town that people are saying is aggregating their symptoms.

BASCOMB: And yet the governor and, from what I understand, EPA Administrator Regan, have both been to East Palestine, drank the water, showed everybody that it was safe and said, you know, everything's fine, we're monitoring the situation. But that doesn't line up with the lived experience of people that live there. To what degree is there a credibility gap here?

BOTTAR: I think there definitely is. I mean, I think that there is now this lack of trust in these government agencies, both because what they're saying isn't matching up with what people are experiencing and also because they really aren't able to answer the questions that residents actually have, which is: can my kids live here safely? What is the long term impact of this going to be? Are our pets safe? Is the water going to be safe in ten years? These are some questions that, you know, really no one knows the answer to and it's making residents just feel very, like, not able to trust the people who are trying to answer their questions.

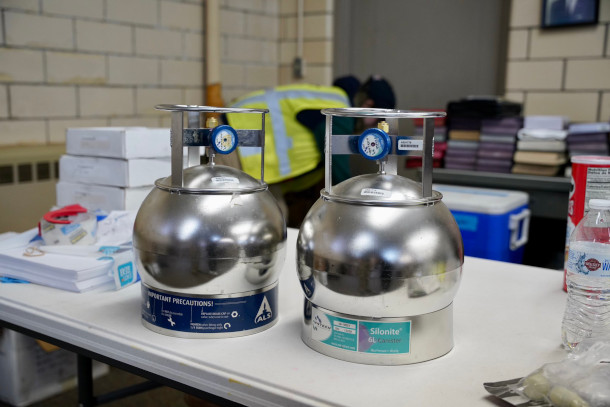

Stainless steel canisters used by the EPA to collect and test air samples. (Photo: U.S. EPA, public domain)

BASCOMB: Now, Ohio is a really important agricultural state. How are farmers being impacted, if at all, from the spill?

BOTTAR: Yeah, and especially this area. When I was in East Palestine, I spoke to people that live in the town itself and also people in the surrounding towns and even the surrounding counties. And they told me that a lot of their produce and meats and vegetables come from East Palestine in the Columbiana County. So we really don't know right now what the impacts will be. I have heard reports of farm animals getting sick and dying. But the Ohio Department of Health said that they have not been able to substantiate any of those claims. I think that the Ohio veterinarian, the state veterinarian, had been on the ground and urging people to talk to their vets to document any symptoms their farm animals or pets were having. So it's pretty unclear at this point how agriculture will be impacted. I will say part of the remediation efforts that Norfolk Southern in conjunction with the EPA will be doing is soil testing and sampling and remediating soil and water in the local creek. But at this point, it's pretty unclear, like, long term how this will affect that area.

BASCOMB: And some of these chemicals also reached local waterways and rivers. What's the latest information about how those ecosystems were affected?

BOTTAR: The vinyl chloride and other chemicals did get into the local creek and killed hundreds of fish. I'm sure we've all seen tweets and videos and pictures of dead fish in the water. It was very scary. They are currently remediating that local creek, they've, like, dammed it off on both ends around the spill, and they're rerouting the water around that impacted part. There were some reports of contamination in the Ohio River, but at this point in time, the governor said last week that there's no concern for the Ohio River right now. There's no contamination any longer. And there's just going to be some continued monitoring just to be extra safe. But he said there's no concern there.

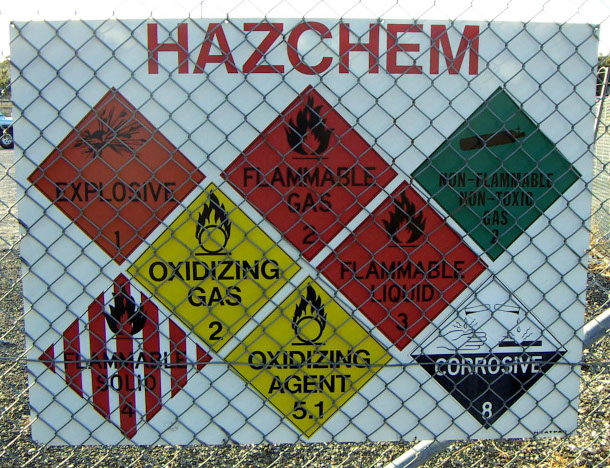

BASCOMB: Now, you said at the beginning of our chat here that it took about a week for the EPA to tell people what chemicals were in that train and what they needed to be concerned about. Now, my understanding is that that's kind of standard, that, you know, communities where these trains are rolling through, they don't have access to the information. The train companies aren't obligated to tell people what they're carrying, what hazardous chemicals might be on board. What are you hearing about, you know, potential changes to that rule and how we might avoid this situation in the future?

BOTTAR: Yeah, that's completely correct. From the beginning, I spoke to environmental advocates, and I've also seen rail unions speak out about this. They say, we've been calling for this greater accountability and greater transparency from freight rail companies for years. That communities should know what's rolling through their town on tracks. I mean, I grew up really close to train tracks. A lot of my coworkers did.

Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg visited East Palestine, Ohio, to tour the site where a train wrecked nearly three weeks ago as the government faces growing criticism over the federal response to the derailment. https://t.co/apGvvfGTpc

— The Associated Press (@AP) February 23, 2023

BASCOMB: Yeah, me too.

BOTTAR: Lots of people grow up on train tracks. I never thought once, what's on that train? And we should know what's on that train. And I mean, people are saying it's far and few derailments that happen. For the most part, trains are very safe to carry these hazardous materials–they are–that's the safest way to carry hazardous chemicals. But in the instance like this where derailment does occur, communities should be able to make contingency plans, to make public health plans, to make environmental plans. So that's kind of what advocates have been calling for years. And I think this might actually–I've seen a lot of momentum–be the push to make that change happen. So there have been calls. Governor Mike DeWine, our Ohio Senators Sherrod Brown and J.D. Vance, all have called for Congress or the federal government to take up this issue and to put stricter regulations on freight rail companies. That could be like, labeling train cars better so communities know what's on them, upgrading safety systems like brakes, making it so they have to employ more people so they can do better inspections. Some of this stuff would just be reinstating some Obama era rules that were rolled back during the Trump administration. But there is a really big push for Congress to take action. If Congress did it, then it would obviously be more permanent than if the Biden administration made a rule which then a future president could just roll back like we saw this time. So there is a very big push for that to happen from both Democrats and Republicans and lots of talk about working across the aisle to get this legislation passed.

BASCOMB: Abigail Bottar is a reporter for Ideastream Public Media in Ohio. Abigail, thank you so much for your time today.

BOTTAR: You're welcome.

BASCOMB: We reached out to Norfolk Southern for a response. They replied by email with a list of actions they’ve taken including more than 4 million dollars in direct financial assistance, hundreds of in-home air quality monitors and remediation efforts for soil and waterways. To see the full response from Norfolk Southern visit the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Abigail Bottar on Twitter

- USA Today | “Ohio Train Derailment Fact Check: What's True and What's False?”

- CBS News | “What To Know About Vinyl Chloride and Other Hazardous Chemicals on the Train that Derailed in Ohio”

- Full Statement from Norfolk Southern

[MUSIC: Antonio Carlos Jobim, “O Morro Nao Tem Vez” on Antonio Carlos Jobim-The Composer of “Desafinado,” Plays, by Antonio Carlos Jobim, Verve Master Edition]

Beyond the Headlines

Ukraine is demanding that Russia pay for environmental war crimes. (Photo: Oleksandr Ratushniak. Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: It's time to take a trip now beyond the headlines with Living on Earth commentator, Peter Dykstra. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby. It's the first anniversary of Russia's invasion of Ukraine and the Ukrainian Environment Minister Ruslan Strilets says that environmental damages to Ukraine as inflicted by Russia amount to an estimated $48 billion in pollution, contamination of land and water, health related problems, and so many other things that have gone into the ruthless bombardment of Ukraine.

BASCOMB: Yeah, we did a story a while back about cetaceans, dolphins and porpoises washing up dead in the Black Sea as a result of the war. You know, it's hard to talk about the environment when thousands of people have also died. But as you're telling us, you know, pollution in the form of water and air is going to affect those people for a long time.

DYKSTRA: As you mentioned the cetacean deaths are one more side of this, who knows how many other aspects of this will be recovered after this war ends, if it ends.

BASCOMB: Well, what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Another billions of dollars in price tag in bird flu, avian flu here in this country, there's a second year it's kind of rare that avian flu outbreaks go into two years affecting everything from a government cost compensating farmers now believed to be somewhere about two thirds of a billion dollars to the farmers costs that aren't compensated to food wholesalers and retailers, grocery stores. And of course, you may have noticed what it costs when the consumer buys chicken or turkey or eggs.

The bird flu outbreak has cost the government roughly $661 million and added to consumers' pain at the grocery store. (Photo: Laughlin Elkind, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Yeah, I think eggs are up to about a $5 a dozen now. It's you know, hitting everybody. But as far as I understand it, there's only been one confirmed case of human bird flu, which wasn't even very serious. So there's that silver lining.

DYKSTRA: But there's concern that some day it may spread to humans. There's already evidence that it has spread beyond the bird population to other mammals ranging from bears and marine mammals like whales and seals. And of course, non food birds like eagles have also been said to literally be falling from the sky, not in huge amounts, but in amounts that cause concern for the spread of avian flu beyond chickens and turkeys, possibly someday to humans.

BASCOMB: Well, what do you see for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: This one goes way back to the very end of the 18th century, February 25 1799, a law called the Federal timber purchases act, one of the first conservation laws enacted by this new country, the United States. Brought in mainly to protect forests in the south where Live Oak, our common tree, those oak trees were prized, mostly in shipbuilding, and Congress wanted to protect those forests and wild lands. And what has happened since then, is that the law was strengthened to cover more forests in 1817. All of this eventually evolved a century later into the US Forest Service, which now has national forests from coast to coast.

Created in 1799, the Federal Timber Forestry Purchases Act was the first forest conservation measure in U.S. history, appropriating $200,000 for buying key forest land. (Photo By João André O. Dias, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, so 1799 What happened to those forests when we switched from wooden boats to steel?

DYKSTRA: Well, when iron clad boats and military ships came about much later in the 19th century, we found so many other things, to consume timber for anything from paper to homes for a rapidly booming country. And we found plenty to do with our timber. And it became under greater and greater stress where there still is the old, tired, worn jobs versus environment issue being played out today in places like the Tongass National Forest and Alaska, and so many other forests throughout the Western US.

BASCOMB: All right. Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra as a commentator for living on Earth. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Bobby, thanks a lot, and I'll take to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on the stories on the living on Earth website. That's loe dot org.

Related links:

- CBC “Ukraine Wants to Make Russia Pay for Environmental Toll of War”

- AP News “Bird Flu Costs Pile Up As Outbreak Enters Second Year”

- Today In Conversation “First Federal Timber Act Passed”

[MUSIC: Ali Farka Toure & Toumani Diabate, “Sabu Yerkoy” on Ali and Toumani, by Ali Farka Toure and Toumani Diabate, Nonesuch Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – A recent study finds some workers are not getting accurate information when it comes to chemical exposure in the work place. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Leo Kottke, “Peg Leg” on Peculiaroso, by Leo Kottke, BMG Entertainment]

Workers Left in the Dark About Chemical Risks

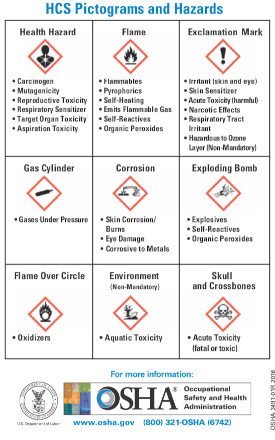

A recent study of 650 Safety Data Sheets found that thirty percent contained inaccurate hazard warnings. (Photo: Tom Blackwell, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA, requires that employers must make information about workplace chemicals available to their workers in the form of Safety Data Sheets. But a recent study of 650 Safety Data Sheets found that nearly a third of them contained inaccurate hazard warnings, often downplaying the risk associated with chemical exposure. For example, Vinyl Chloride, is the same chemical released from the derailed train in Ohio that we talked about earlier in the show. It’s a known human carcinogen but the safety data sheets used for many products containing vinyl chloride only mentioned skin, eye, and respiratory irritation. A full fifteen percent of the products containing cancer-causing chemicals failed to warn of cancer as a risk on their safety data sheets. Workers are often exposed to hazardous chemicals in products like cleaning solvents, paints, and lubricants and Charlotte Brody says failure to disclose that risk undermines worker safety. Charlotte is the Vice President of Health Initiatives for Blue Green Alliance, which co-produced the recent study. Charlotte, welcome to Living on Earth!

BRODY: Thank you.

BASCOMB: So what exactly were you looking to learn with this report? And what prompted the investigation?

Employers are required to provide their workers with information about the hazards of workplace chemicals in the form of Safety Data Sheets. (Photo: OSHA.gov)

BRODY: Safety Data Sheets are the fundamental piece of information that every workplace and every worker is supposed to have access to, that tell them if a chemical is dangerous, so that they can protect themselves and work with their employer maybe to find a safer product to use. If the information on this fundamental basis of all hazard communication isn't accurate, the whole idea of how to protect workers from dangerous chemicals falls apart. And that's why we wanted to do this study. There were two studies in the literature, both very small, that showed the inaccuracy of Safety Data Sheets, and the challenge we set out for ourselves is to see if you could automate the process of reviewing Safety Data Sheets and seeing if there was a warning that the chemical could cause birth defects if the chemical could cause birth defects, if there was warning that the chemical could cause cancer if the chemical caused cancer.

BASCOMB: And so these Safety Data Sheets, workers might find them what just like pinned on a cork board in their break room or something like that? Or is this something that's actually, you know, physically handed to everybody who might encounter these products?

BRODY: The law says they have to be accessible. So some employers have an app that every one of their employees can access that has the library of all of the chemical products that are being used in work. In some places, it's available in print in a loose leaf binder, old school, in you know, near the watercooler or in the break room, but it's supposed to be accessible, either virtually or physically so every worker can look at what the hazards are that they're facing.

BASCOMB: And so how many products did you look at here?

Many cleaning products, paints, and solvents contain potentially hazardous chemicals. (Photo: Marco Verch, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BRODY: We only looked for chemicals that we called "consensus chemicals," chemicals that everyone agrees are carcinogens, you know that the United States and Europe and Japan and Australia all say benzene, for example, causes cancer in people. And so we looked at 35 chemicals across 650 Safety Data Sheets.

BASCOMB: And so what were the main findings of your study? To what extent were these Safety Data Sheets inaccurate when outlining the known hazards of these consensus chemicals?

BRODY: So even though we were only talking about chemicals that everyone agrees are dangerous, 30% of the Safety Data Sheets we looked at weren't warning of the hazard. And interestingly enough, the most common missing hazard was reproductive hazards, the chemicals that a woman worker could be exposed to, and they would show up as a birth defect in her child, or a chemical that a male worker might be exposed to, that would lead to him being infertile. Those chemicals were the most often missing their warning.

Twenty one percent of the Safety Data Sheets containing chemicals that harm reproduction failed to include this hazard. (Photo: Anna, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: So these are chemicals that, you know, many governments agree are dangerous, and yet workers are still coming into contact with them. I think that, you know, might be somewhat surprising to people that this is still such a hazard if everybody knows, you know, if governments agree that they're dangerous.

BRODY: Yes. And that was the second reason for why we did this. First there needs to be accuracy about the danger, so that you can figure out how to just replace that danger with something a lot safer. But if the hazard isn't there, if the warnings aren't there, how would a worker or an employer know that maybe it's time to look for a solvent that doesn't destroy the nervous system? You know, maybe it's time to look for a way of making a plastic without exposing workers to a chemical that we know causes cancer in people.

BASCOMB: So how would the average person determine the accuracy of the Safety Data Sheets for products that they're using in their place of work?

BRODY: We're figuring that out. So there's a pretty good resource for people in the United States called PubChem that comes out of the National Library of Medicine, that you can type in a chemical name, and it will tell you the hazard. But it's a lot of work to do that by hand, right, to like look at, you know, a product might have 40 chemicals, 12 chemicals, depending on what it is, and to go into PubChem and to look for every single chemical and if the hazard is there, it's a lot of work. And what we're trying to figure out is how we could create a piece of software that you pull up a Safety Data Sheet and it reads the chemicals and knows the hazards of those chemicals, and tells you if the warnings on the Safety Data Sheet are accurate. That's what we did in this 650 SDS sheet pilot. And it's what we hope we can do to make this easier.

Fifteen percent of the Safety Data Sheets containing cancer-causing chemicals failed to warn of carcinogenicity. (Photo: Holly Gramazio, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: What role should the government be playing here? I mean, this seems like something that you would expect more regulations around.

BRODY: The Biden administration now has put more money than any time since the New Deal in trying to figure out how to build a new industrial economy. A lot of it is about clean energy. But it's also just about cleaner, safer manufacturing. My hope is that this new investment in how to rebuild a US economy will also mean from the beginning thinking how we make stuff so it benefits the people who are making whatever product, it's made as safely as it can be made. It's made in a thoughtful way so it improves lives in the community. It doesn't pollute, right, it creates new forms of safer energy. And part of that is holding employers who will be the beneficiaries of this new investment to a much higher standard than we have in the past.

BASCOMB: Charlotte Brody is the Vice President of Health Initiatives at BlueGreen Alliance. Charlotte, thank you so much for your time today.

BRODY: Thank you so much.

Related links:

- BlueGreen Alliance | “Obstructing the Right to Know: A BlueGreen Alliance/Clearya Analysis of the Chemical Industry’s Health Hazard Warnings on Safety Data Sheets”

- PubChem | “Explore Chemistry”

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration | “At-a-Glance OSHA”

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration | “Hazard Communication: Overview”

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration | “Hazard Communication Standard: Safety Data Sheets”

[MUSIC: Diana Krall, “Almost Blue” on The Girl in the Other Room, by Elvis Costello and Chet Baker, Verve]

Dolphins and People: Fishing Buddies

The dolphins corral migratory mullet fish toward the water’s edge, making it easier for the fishermen to catch fish. (Photo: Dr. Bianca Romeu, Departamento de Ecologia e Zoologia, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina; Florianópolis, SC 88040-900, Brazil)

BASCOMB: In the coastal community of Laguna, Brazil, artisanal fishers make a living from casting their nets for migrating fish but they aren’t doing it alone. Many fishers have an unexpected fishing partner. Dolphins. Until recently, scientists weren’t sure what the dolphins were getting out of it. But research recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences appears to solve the mystery. For more, I’m joined now by Mauricio Cantor, an Assistant Professor of biology and behavioral ecology at Oregon State University and the lead author of the study. Mauricio, welcome to Living on Earth!

CANTOR: Thank you very much. Thanks for having me here.

BASCOMB: So what exactly does this cooperative hunting look like? You know, how do the dolphins and humans interact in this way?

CANTOR: So this cultural practice has been going on for over a century now. And only recently, we started to understand exactly how it works and what each species is gaining from this. So if you go to Laguna right now, you see probably a couple of artisanal fishers standing at the beach waiting for the dolphins to approach. They know that just by going to fish by themselves, then they're not going to get pretty much anything out of this. So when the dolphins approach to the coast, everybody runs into the water, and they can wait there until the dolphins kind of work the fish around, push them towards the coast. And then there's this very specific moment where the dolphin changes its behavior and does this signal that the fishers interpret as the right time and place to where they should cast their nets. And then the dolphins will dive and wait for more or less ten to fifteen seconds for the nets to close over the fish and then they will engage in their echolocation clicks, which suggests that they're really homing on the prey. And then after that, they will both part ways and hopefully with lots of fish.

The fishermen’s nets break up mullet schools, allowing dolphins to chase down stragglers and get their fill. (Photo: Alexandre Machado, Departamento de Ecologia e Zoologia, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina; Florianópolis, SC 88040-900, Brazil)

BASCOMB: So it's easy to see what the humans are getting out of this. The dolphins are sort of corralling the fish towards their nets. But what are the dolphins getting here?

CANTOR: So since this interaction has been around for over 100 years, we would imagine that the dolphins are also gaining similar benefits. Otherwise, they would just do something else. So both predators, humans and dolphins, they have the same goal of catching fish, but they have different strategies. The fishers they want most of the school, so that's why they use their tools, their nets. But the dolphins can only catch one fish at a time. And those are big fish there, they can be over one kilo or 60 centimeters. And what we saw is that when the nets kind of trap the mullet school underwater, it makes it much easier for the dolphins to catch their fish as well.

BASCOMB: So is the idea here then that the majority of fish end up in the nets but there's a few stragglers outside the nets that are easier for the dolphins to catch, because they're not in a large school that's hard to navigate?

Fishermen are seventeen times more likely to catch fish when the dolphins are working with them. (Photo: Dr. Fábio G. Daura-Jorge, Departamento de Ecologia e Zoologia, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina; Florianópolis, SC 88040-900, Brazil)

CANTOR: Exactly. So a fish school is actually a textbook example of anti-predator strategy. And this is true for these mullet fish, this primary target of this fishery. They migrate in these very large, fast moving fish schools. Similar to a flock of birds flying, they make those collective decisions really quick. And that makes it really difficult for the dolphins to catch. Now a fish outside of that school, it's an easy target for the dolphins. They can out swim them and they can catch really easy.

BASCOMB: And I understand you have some data that actually quantifies how much more successful the fisherman and the dolphins are. Can you tell us about that, please?

CANTOR: So by sitting at the beach and watching this for hours in 2018 and 19, we recorded over 4000 interactions like this. And then, you know by counting how much fish and how much biomass the humans get out of this, we estimated that they're 17 times more likely to catch any fish when the dolphins are working with them. And they tend to get up to four times more biomass of fish when the dolphins are working with them, compared to when there's no dolphins in the area.

BASCOMB: And I understand that the dolphins that partake in this interaction with humans are more likely to survive to adulthood. Is that right? Can you tell us about that?

The cooperative dolphins, or those that regularly engage with the fishermen, are thirteen times more likely to survive to adulthood compared to those dolphins that hunt on their own. (Photo: Dr. Carolina Bezamat, Departamento de Ecologia e Zoologia, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina; Florianópolis, SC 88040-900, Brazil)

CANTOR: What we found from our modeling is that the dolphins that regularly cooperate with the artisanal fishers, what we call the cooperative dolphins, they're 13 percent more likely to survive to adulthood, compared to the other noncooperative dolphins, the ones that never engage in this cooperation with the net casting fishers. And there's a couple of reasons for this. We are yet to understand if the amount of food that they catch promotes their survival. But one thing that is much more clear right now is these cooperative dolphins, they spend a lot of their time interacting with these net casting fishers, and these kinds of net casting fisheries, they're pretty safe for the dolphins, so you'd have a low probability of being tangled in that net. Now the noncooperative dolphins, they will range over a much larger area to catch fish for themselves, and over this larger area they are exposed and often encounter other types of fisheries, including illegal fisheries, such as drift nets and trammel nets. They are set to kill anything that, you know, hits on them, including dolphins. So by not staying with the artisanal fishers, the noncooperative dolphins actually have this additional source of mortality.

BASCOMB: How close of a relationship is this with, you know, individual dolphins? Could the fishermen actually recognize and say, yeah, that's a dolphin I know, and this one's not going to give me the time of day?

This method of cooperative hunting has been part of Laguna’s culture for over 150 years. (Photo: Alexandre Machado, Departamento de Ecologia e Zoologia, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina; Florianópolis, SC 88040-900, Brazilga)

CANTOR: Oh, yeah, absolutely. Actually, knowing who is who on the dolphin side is really key for the interaction to take place in the right form. So the experienced fishers can tell apart pretty much all the individual dolphins. They can tell them apart from different natural marks that they have on their dorsal fins on their body, but also the way they behave. They can clearly distinguish between what they call good dolphins, the cooperative ones, the ones that you know, regularly approach and interact with them but are also really skilled at bringing the fish, giving that behavior cue that they interpret as the right time to cast nets, all of this. So they know these good dolphins, where they are in the area, everybody runs into the water because it's almost guaranteed they will catch fish.

BASCOMB: Mauricio Cantor is an Assistant Professor of Biology and Behavioral Ecology at Oregon State University. Mauricio, thank you so much for your time today.

CANTOR: Thank you very much. It's been a pleasure talking to you.

Related link:

Proceedings of the National Academy of Science | “Foraging Synchrony Drives Resilience in Human-Dolphin Mutualism”

[MUSIC: No em pingo D’agua, “Assanhado” on Receita de Samba, by Jacob do Bandolin/arr.Rodrigo Lessa, on Contemporary Instrumental Music from Brazil-A Windham Hill Sampler, Visom/Windham Hill Records]

Last Reminder! The Next Chapter of the Living on Earth Book Club

BASCOMB: The cuddly Koala is one of the most charismatic and beloved species

on Earth. But massive wildfires and habitat loss threaten their very existence. In her new book “Koala: A Natural History and an Uncertain Future” award-winning Australian author Danielle Clode takes us on a journey up into the trees to discover the remarkable physiology and ecology of koalas. She joins us for the next Living on Earth Book Club livestream on March 2nd at 6:00 pm Eastern and you’re invited! For details and to register for this free event go to loe.org/events.

Related links:

- CLICK HERE to register for this upcoming live event

- Purchase a copy of Koala: A Natural History and an Uncertain Future (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: No em pingo D’agua, “Assanhado” on Receita de Samba, by Jacob do Bandolin/arr.Rodrigo Lessa, on Contemporary Instrumental Music from Brazil-A Windham Hill Sampler, Visom/Windham Hill Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Residents in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley are looking to their enslaved ancestors to help fight the expanding petrochemical industry. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Playing for Change, “Samba de Viola/Sangue Brasileiro” on Listen to the Music, live outside]

The Power of Black History

The Slavery Museum at the Whitney Plantation, the only former plantation site in Louisiana with an exclusive focus on slavery. (Photo: Cheburashka007, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

For more than 100 years before emancipation, enslaved people of African descent were forced to work the land along the Mississippi River near the city of New Orleans. They toiled to grow sugar cane in the rich soil and enriched white land owners with their free labor. Now centuries later, the legacy of slavery persists as the descendants of enslaved people live and work in one of the most polluted regions of the country, the 85 mile stretch along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans known as Cancer Alley. African Americans in the region disproportionately live with health problems associated with exposure to the roughly 150 petrochemical plants that give the region its infamous nick name. And industry in Cancer Alley is still expanding. The Taiwanese company, Formosa, is pushing for a new 9.4 billion dollar petrochemical plant to be built on a piece of land known as the Buena Vista Plantation. But genealogists have uncovered evidence that enslaved people were buried on that land. And since several laws prohibit building on historical sites activists are hoping that they can stop the expanding petrochemical industry by telling the stories of enslaved people in the region. In honor of Black History Month we would like to share some of those stories as well. Lenora Gobert is a genealogist for the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, an activist group against Louisiana’s expanding petrochemical industry. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: Please tell me how your genealogical research connects to resisting heavy industry?

A petrochemical plant owned by Formosa. (Photo: Formulanone, Flickr, CC BY SA 2.0)

GOBERT: Well, it's really interesting. And the way I like to characterize it is, if you're familiar with some of the culture of Louisiana, there's something called a second line, which traditionally has been the line of people that have followed the casket and the musicians taking somebody to a burial site. And that's how I look at my work. There are people who have been fighting the fight against the petrochemical companies. And this includes the community organizations as well as lawyers and other environmental organizations working along with them. I am coming behind them to help document the claims that are being made about ancestors being buried on the plantations and therefore being threatened by the expansion of petrochemical companies. And people who are from the area have always said that there are grave sites there, there are people buried there. So this started sparking the interest of other community members and people working at the Bucket Brigade, to ask me to start looking into it and see what I could find. And yes, in fact, from the St. James courthouse, I went to the mortgage records to find out which enslaved people had been mortgaged by Benjamin Winchester, who owned the Buena Vista plantation. And a lot of people don't know that enslaved people were mortgaged to raise money to keep the plantations running. And there was an organization, or a financial organization called the Consolidated Association of Louisiana Planters that Benjamin Winchester mortgaged his enslaved people to. So I researched it and found out that their papers are held at the Louisiana State Archives* in Baton Rouge. And I went up there, and they're just organized by month and by year in boxes. So I went there, and I had to start looking through documents from about 1820, up until about 1850, to see what transactions of Benjamin Winchester I could find. And in one of the papers, there was -- he had a few papers where he had mortgaged people and he had them listed, but in this particular one, he had the men listed together, the women and the children. And there was nine year old Rachel, and next to her name was written the word "dead" - D-E-A-D. And that sent shivers up my spine, because obviously, Benjamin Winchester had intended to mortgage her, she was on the list with everybody else, but she died before he could mortgage her. So if she died, and she's from that plantation, logic and everything that we know historically about this institution says that she is buried on Buena Vista plantation, in the enslaved peoples' burial site. So that was how the story came about. This work that I did and this document that I found, starts setting the stage for other documents to be found in additional situations, to provide this as a tool to help stop these petrochemical companies from expanding further.

CURWOOD: So what does the records tell you about Rachel, the slave aged nine, now dead, on this plantation?

GOBERT: Nothing, so far. Not many records were kept on enslaved people, as I'm sure you know. And a find like this is for me and for a lot of other genealogists extremely rare and very special, because it starts giving names and locations to people and what may have happened in their lives. But again, she was only nine years old. So I haven't revealed this yet outside of just talking to one or two people, but I have found the document where Benjamin Winchester purchased her and her mother and two brothers. So I know where she came from. I know who sold her, but I don't know anything about her life other than that, and that she died at nine years old.

Plastic nurdles created by ethane cracker plants like the ones in Cancer Alley. Plastic nurdles are the primary feedstock of plastic manufacturing. (Photo: Mark Dixon, Flickr, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Well, so, okay, where did she come from? Who sold her?

GOBERT: Well, there was an enslaver, or a slave trader, and his middle name was Fontaine, last name Rose and from Kentucky**. So that's where he brought her from. I don't know if she was born there; likely, because she was so young. I don't know where her mother came from. Her mother's name was Eve, her mother was 20 years old when she was purchased by Winchester with her children. But their history earlier than that, I don't know yet. It takes a lot of digging, if you can find anything at all.

CURWOOD: Lenora, these days if we want to mortgage something to get a loan from a bank, we mortgage property and of course, slaves were property. But we typically mortgage land and the buildings on it. To what extent does this indicate that the, as far as the banking system was concerned, slaves were worth more than the land that they were being asked to work?

GOBERT: Absolutely. The enslaved people were the most valuable asset any of these people had, they were worth more than the land or the buildings by far. And that's what fueled the industry. And that's what, I think about the northern states that benefited from slavery also, we never really talk about that. But the banks up north also dealt with the enslaved people, mortgaging them or extracting their value, if you will, to provide financing for all kinds of building projects that people had at the time.

CURWOOD: So how do you feel that uncovering stories like Rachel's help to push back against the expansion of the petrochemical industry?

GOBERT: Well, you know, these are sacred sites, actually. But the fact that this area is considered so vital to the US economy, that this heavy industry must be sited there, means that they will do pretty much anything that they need to do to overlook the fact that there are human beings who are buried all along the river, there are thousands of these burial sites. But they do not want to acknowledge them, because of course, it prevents them from building there. So the sacred sites of the enslaved people count for nothing. And this is my opinion, but I believe that to be totally true.

Sugarcane fields in front of the Marathon Garyville refinery between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana. Enslaved African Americans once toiled to grow sugarcane on plantations, and today petrochemical plants are replacing agriculture in the region. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: So the records that you found for Rachel indicate that she and her mother came from the Kentucky area. And there's a saying in the American English vernacular of being "sold down the river." How does that saying pertain in this case?

GOBERT: Well, technically, she wasn't sold down the river. But in terms of the concept, it's pretty much the same thing. Because, as you probably know, a lot of the enslaved people from the northern states, as well as the Mid-Atlantic states, were sold to the lower South. And a lot of those were to work on these sugar plantations. So conceptually, it was the same idea. Everybody's being moved south, because the labor needs are so high.

CURWOOD: What were the conditions on the sugar plantations for the slaves that worked there?

GOBERT: I'm not an expert on this, but it was brutal. And what's so interesting to me is when I first moved to New Orleans, I was really surprised how cold it can get here, how very cold it can get, in the 40s. So I started thinking about the enslaved people who were in these cabins, which, of course, are not insulated, they may have this little fireplace in the middle where they can get a little bit of heat. But their clothes were thin, I guess they had one set of clothing, they may have had one thin blanket, can you imagine how it would have been for them, even when they weren't working? It had to be horrendous for them. And they were so resilient. Most of them, many of them, lived through these conditions, to produce all of these descendants. I think everybody should revere them. They should feel proud of them. They should say their names. And the only way we can get to say their names, is looking at these documents to find out who they are.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about the money some more. How lucrative was the sugar business? How well were these white slave owners doing financially using these enslaved people?

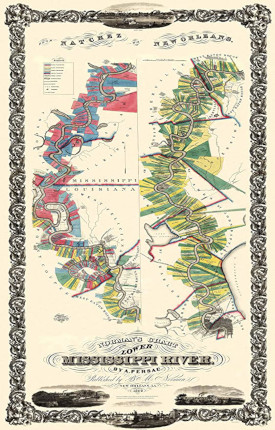

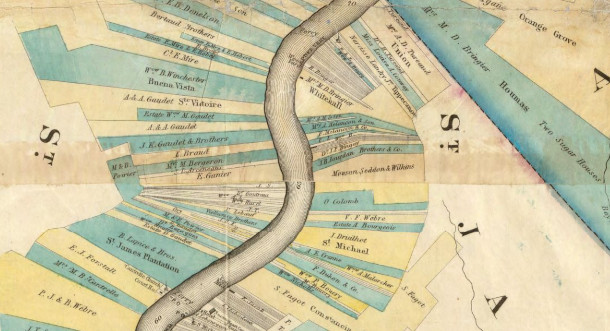

Pictured above is an 1858 Persac map of the Mississippi River in relation to plantations in Louisiana. (Photo: Courtesy of Lenora Gobert)

GOBERT: Well, from what I've read, and I know it to be true, there were more millionaires along the river than anyplace else in the United States when these plantations were operating. It was so lucrative, this sugar industry, it was the fuel that ran the economy for the United States and the globe. I mean, England was so complicit in this. I'm hesitating right here, because it was so big. People don't think about how big this industry was globally, and that it all came from the labor of these enslaved people. But these people were extremely rich, extremely rich.

CURWOOD: Well, sugar is addictive.

GOBERT: [LAUGHS] Yes.

CURWOOD: And I think once the Europeans understood about sugar cane, they were able to sell as much as they could make.

GOBERT: Well, that's right. And it's so interesting, again, I'm stepping a bit outside my area of expertise, but I'm thinking about the LNG facilities being built in Cameron Parish now. And everybody keeps talking about how great this is for the United States, how great this is for the United States. But that liquid natural gas is going outside of the United States, and it's going to Europe, and it's going to other places. And it's not benefiting the United States. It's not benefiting us, really. That's the same type of industry and mentality that was utilized with the sugar plantations, it's the same. The plantation system is alive and well in South Louisiana.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I was gonna say, the Mississippi River was home to many slave plantations, and of course, there are many descendants of the slaves still living there. And I believe it's on the scale of 150 petrochemical plants that are today spewing out contaminants associated with cancer, but many other diseases as well. What does that tell us about systemic racism in Louisiana? For that matter, what does it say about systemic racism in the United States of America?

GOBERT: That it's been there since the peculiar institution was invented, and it's never gone away. And because it's not right in our face the way it was in the 1700s, 1800s, it feels like things have gotten better. But you're right, institutionalized slavery is more insidious, it's there. It keeps people of color from reaching their full potential, from participating in the full economy of the United States. And for some reason, people don't want to hear this. They don't want to know this. And I believe that through the work that people like me are doing, genealogists, because we document individual family stories, and we document community stories, and we let people know what has happened and what is continuing to happen, and tie those things together for them -- plantation life is still going on to this day. It's in a different form, but it's still there.

Pictured above is an 1858 map from Persac's Mississippi plantations map, that clearly shows the site of the Benjamin Winchester Buena Vista plantation at the top left. (Photo: Courtesy of Lenora Gobert)

CURWOOD: Are you suggesting that if you talk back against the chemical plant in your neighborhood, that you or your family is likely to lose their employment, their livelihood, there is no freedom for those folks?

GOBERT: I can't speak to that, specifically. The people who are in the communities and who are fighting against these plants, they would be able to tell you definitively whether or not that is true. But I do know just from talking to them that because people have jobs there, of course they're afraid to speak out. They don't want to lose their job. That's the only source of livelihood, everything else is being systematically pushed out. The communities are being pushed out, they're denuding the land of people. It's amazing. It's so systematic, and individuals fighting against huge corporations, huge money making enterprises is very, very difficult. As a lot of activists and people who have been put upon in this country know, it's very difficult.

CURWOOD: Now, what are some of the barriers that African Americans descended from slaves face in trying to trace their history?

GOBERT: Well, the main issue, I think, is the lack of documentation. A lot of families have oral histories, that when you dig into them and find documentation on the families, there are always nuggets of truth in their oral histories. They may be exaggerated, they may have changed over time. But there are nuggets of truth. And you can use those to help you find the documentation about the history of these families. But the main thing is that we've basically been written out of history, or haven't been written into history for the most part. So unless you can find the documentation, it's difficult, it's very difficult.

CURWOOD: So to what extent is documenting and respecting the resting places of enslaved people a form of reparation?

GOBERT: I'm glad you asked that question, because I think we need to start really looking outside the box in terms of what reparations are. And one of the things that is important for me as a researcher is making documents of enslaved people, and even after they were free, making those documents much more readily available to be researched. My main topic, because I'm in Louisiana, is, well, there's more than one but a huge one for me is the Catholic Church. They have so many records, because they documented the lives of enslaved people, they have so many records that I feel should be made much more easily accessible. They should be using Catholic scholars to research some of this information and bring it out so that we all know and understand what's been going on with these enslaved people. The other thing is, too, that there are so many records in courthouses, these records that I talked about earlier, the mortgage documents that have enslaved people in them, they are somewhere on the shelves, all tattered and torn, falling apart, because they're not deemed to be important. And I'm sure there are other records in these courthouses that have information on enslaved people, but they're not easily accessible. So reparations -- that to me, is opening up the archives and every place that houses documents where there are documents pertinent to enslaved people's lives, and making them easily accessible.

Lenora Gobert is a genealogist for the Louisiana Bucket Brigade. (Photo: Courtesy of Lenora Gobert)

CURWOOD: How can reconnecting with one's ancestors be empowering? What's the power you get from this?

GOBERT: I love that word "empowering" because I truly believe that a big part of the problem that we have in the United States is, with people who are of African ancestry, is a lack of self esteem. And that lack of self esteem for me, comes from them not knowing where they come from, what their people accomplished in this country. And once you started getting into those documents, you become amazed at what some of these people did after slavery and sometimes even before. So, if we knew where we came from and the contributions that our families made, not only that the resilience that they had to get through that slavery period, so that they are here today, I think they would really start having more self esteem, knowing who they are, feeling much better about themselves, and being able to move through this country in a more positive sense and more positive attitude and doing more things for themselves. That's my belief.

CURWOOD: Why is your work part of the quest to achieve environmental justice?

GOBERT: Environmental justice and racial justice and social justice, they're all intertwined. And the racial justice that we are trying to achieve, that we want to achieve, that we believe we will achieve, is to keep these communities on the land, where they have been for over 100 years. By these communities staying on this land and fighting the petrochemical industry, that is climate justice for them and everybody else because they will no longer be polluting the Mississippi River. They won't be polluting the land. They won't be polluting the air that has caused Cancer Alley to become Cancer Alley. So it's all connected.

BASCOMB: Lenora Gobert is a genealogist for the Louisiana Bucket Brigade. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

**CORRECTION: The documents of mortgaged enslaved people documented in the Consolidated Association of Louisiana Planters were found in the Louisiana State University Archives not the Louisiana State Archives.

**CORRECTION: Alexander Fontaine Rose was from Kentucky not from Virginia.

Related links:

- The Guardian | “This Nine-Year-Old Was Enslaved in the US. Her Story Could Help Stop a Chemical Plant”

- Louisiana Bucket Brigade

- Don’t miss LOE’s previous interview on cancer alley with activist Sharon Lavigne

[MUSIC: David Chevan and Warren Byrd, “Let Us Break Bread Together” on Let Us Break Bread Together: Further Explorations of the Afro-Semitic Experience, traditional African-American spiritual, CD Baby]

BASCOMB: Next week on Living on Earth climate change is changing the game when it comes to what traits are advantageous in nature.

MOORE: There’s some interesting research in birds where some of their plumage is starting to change as a result of it being too warm.

BASCOMB: And we’ll take a close look at dragon flies and climate change, next week on Living on Earth from PRX.

[MUSIC: David Chevan and Warren Byrd, “Let Us Break Bread Together” on Let Us Break Bread Together: Further Explorations of the Afro-Semitic Experience, traditional African-American spiritual, CD Baby]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Fern Alling, Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Jusneel Mahal, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth