New Exoplanet Revealed

Air Date: Week of March 10, 2023

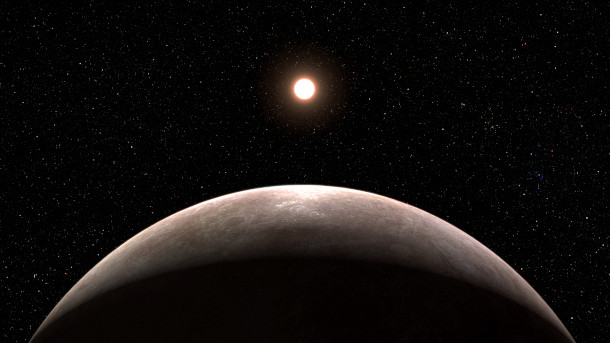

An illustration of LHS 475 b. Scientists are determining whether the newly discovered exoplanet has an atmosphere. (Photo: NASA/European Space Agency/Canadian Space Agency/L. Hustak (STScI))

NASA scientists used data from the James Webb Space Telescope to identify exoplanet LHS 475 b. Exoplanets are planets outside of our solar system that orbit a different star, and can be very difficult to identify. Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill spoke with one of the lead researchers on the project, exoplanet astronomer Kevin Stevenson, about how the finding may help develop a model for identifying planets that are likely to contain life.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

NASA’s James Webb Space telescope has been amazing scientists since it became fully operational last summer. It’s collected beautiful images of nebulas and the distant past, forcing researchers to reconsider how early galaxies developed. And in mid-January, scientists used the telescope to identify exoplanet LHS 475 b. Researchers hope the discovery will help them develop a model for identifying planets that are likely to contain life. For more, we reached out to one of the lead researchers on the project, Kevin Stevenson, he’s an exoplanet Astronomer at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, and spoke with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill.

O'NEILL: Now, what is an exoplanet and what makes them so interesting to study?

STEVENSON: An exoplanet is really just a planet like we understand in our own solar system. But it just so happens to be orbiting another star. So, you know, there are billions of stars in our galaxy. And there are in fact, billions upon billions of planets around those stars. And so it's really just any planet could be big or small, hot or cold, that is out there, orbiting around these other stars, minding their own business having a great time.

O'NEILL: And can you tell me a little bit about the discovery of this new exoplanet LHS 475 b?

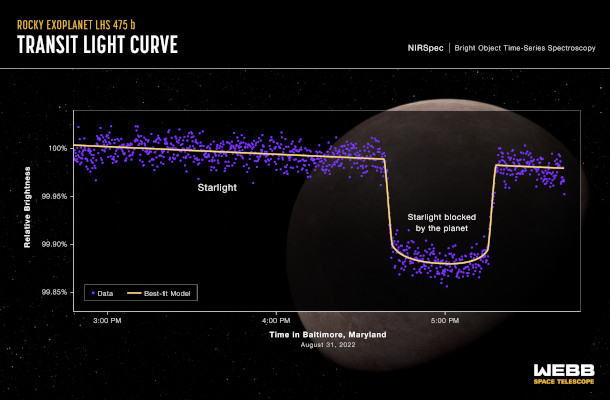

STEVENSON: Yeah, this planet was actually originally a planet candidate. And so it was first detected, at least initially using the TESS observatory. Now, TESS is another NASA mission that has been flying for the past several years, and its primary goal is to search for transiting exoplanets like this one. Now, at the time, it was not confirmed it was what we call a planet candidate. So there had been no follow up observations to validate this as a an Earth-sized rocky planet. And this is where the James Webb Space Telescope really comes into play. We were able to use observations from this new telescope that has large collecting, area broad wavelength coverage, just a fantastic telescope, in order to measure the transit depth of this planet and in fact confirm that it is a planet and not some other false positive signal.

This graph shows the change in brightness of LHS 475 b over time. This data indicates the planet’s size and distance from its star, but not whether it has an atmosphere. (Photo: NASA/European Space Agency/Canadian Space Agency/STScI/L. Hustak (STScI)/Johns Hopkins APL)

O'NEILL: And why is the planet's name LHS 475 b, and for that matter, is there any chance it'll get a colloquial name, so we don't have to keep saying LHS 475 b?

STEVENSON: LHS signifies the survey that it comes from. There are several different surveys that have been conducted, so this particular system actually has multiple names. It just so happens that LHS is probably the first survey, from what we can tell, that actually identified this star as being a nearby M dwarf. So that's what we picked and it is 475 it is the 4705th star in the survey. Now, typically when we name planets, we use B, C, D, E, F, the letters of the alphabet, because A is the primary the star itself. The first planet is B because the star is always A. We do have a nickname for this planet. Some of the students and postdocs in our group are big Taylor Swift Fans, so they labeled it Swifty one b.

O'NEILL: Oh, that's excellent. Oh, Has anyone told her about it?

STEVENSON: I don't think so. This will be news to her.

O'NEILL: Well, based on what we've learned so far about the planet, what are scientists saying? LHS 475 b is like? Is it a rocky planet like Earth? A gas giant like Jupiter? And what are the chances that it might possibly be habitable?

STEVENSON: Well, that's a great question, because based off of what we understand the star is, is an M dwarf, and it's quite small. And that means that we're sensitive to small planets like this one. So just first off, we would never have detected this planet if it were orbiting a sun-like star. And from what we can measure about the size of the signal, we can tell you that the planet is .99x the size of the Earth. But that doesn't mean it's the same temperature. And that does not mean it's habitable. So based off of what we can determine, it's probably closer to 500 degrees Fahrenheit. So a lot hotter. And so chances are a lot of the water has boiled away on this planet. And it could be something like Mars, for example, where it has no or tenuous atmosphere. But this planet could also be like Venus, where it has a high altitude cloud deck with a thick atmosphere, it's really difficult to tell the difference between those two based off of the observations that we've made here, but it is tantalizing to consider the possibilities.

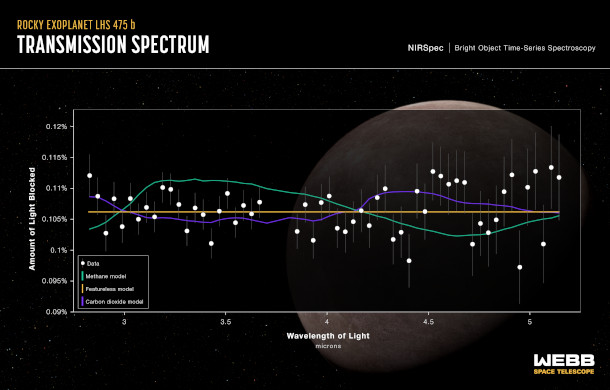

With current data, scientists can’t determine whether LHS 475 b has no atmosphere, an atmosphere made of carbon dioxide, or an atmosphere made of methane. Current data indicates the flatline seen on the graph: wavelengths of light that signify no atmosphere. But with more precision, researchers could see wavelengths indicating the methane model (the green line) or the carbon dioxide model (the purple line). (Photo: NASA/European Space Agency/Canadian Space Agency/STScI/L. Hustak (STScI)/Johns Hopkins APL)

O'NEILL: So how much can be learned from the current James Webb space telescope data on this planet, and how much will need more investigation?

STEVENSON: Right now we have to transit observations of LHS 75 B. From that we can place basic constraints on its atmospheric composition, we do know that the planet doesn't have a giant ball of hydrogen helium atmosphere, like Jupiter or Saturn, Uranus, Neptune. We also know that the planet probably doesn't have a pure methane atmosphere, or something similar to Titan. Now, things get a little bit more confusing when you start considering planets like Venus and Mars, both of which have carbon dioxide, CO2, as their main constituent in their atmosphere, but they're very, very different in terms of the atmospheric pressure. Venus has a lot of atmosphere, where Mars does not. And we can't really differentiate between those two scenarios just yet with the data. So we're looking to have follow on observations, we're going to be getting a new transit observation in the summer of 2023. And we also hope to get a secondary Eclipse observation, this is where the planet passes in behind the star. And from that, we can actually differentiate between our two scenarios, the Venus scenario and the Mars scenario, because a planet with a thick atmosphere is going to have a very shallow Eclipse depths, so very weak signal. Whereas a planet like Mars that essentially has no atmosphere, is going to have a very bright secondary Eclipse measurement. So using these two observations, the transit and the Eclipse, we're going to be able to learn a lot about this planet.

O'NEILL: And what's the importance of figuring out if the planet has an atmosphere? Is it sheer scientific curiosity? Or is it likely to reveal something else about our universe?

STEVENSON: Well, part of this program we have is to observe multiple planets all orbiting M dwarf stars. And what we're trying to determine is whether or not there is a universal divide between planets with and without atmospheres. And this is what we call the cosmic shoreline. The idea is that we want to be able to predict which planets have atmospheres and which ones don't, before investing a huge amount of telescope time into searching for signs of life. And the idea here is that if we can use basic information about the planet, and from that, if we can ascertain whether or not this plant has an atmosphere or not, then we can focus our observations in the future on only those plants that have atmospheres. So there is a long sort of process of trying to find life on other worlds. And it starts with answering the very basic question of which planets have atmospheres and which ones don't. So we're trying to start the first step towards the search for life. And this is the first planet in our program.

CURWOOD: Kevin Stephenson is an exoplanet astronomer at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neil

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth