March 10, 2023

Air Date: March 10, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Nature on the Federal Balance Sheet

View the page for this story

The White House is starting to account for natural capital, the economic value of services provided by nature, when making decisions. Linda Bilmes teaches Public Policy and Public Finance at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government and she joins Host Bobby Bascomb to take a look at this emerging strategy. (08:15)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood and Living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra look beyond the headlines to a United Nations ocean biodiversity protection treaty, along with the newly designated Chilean Tictoc marine park for whales. Then, the pair discuss Antarctica's diminishing sea ice, before looking back to the historic resignation of EPA Administrator Anne Gorsuch-Burford. (05:46)

Indonesia Squelching Biodiversity Research

/ Fred PearceView the page for this story

Indonesia has one of the world’s largest tropical forests and touts itself as a global leader in conservation. But researchers from outside Indonesia say the government is blocking data to assess conservation progress and local scientists fear reprisals if they publish data that doesn’t fit the government’s optimistic narrative. Environmental journalist Fred Pearce joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss. (08:16)

The Human Toll of Pollinator Loss

View the page for this story

A study conducted by Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health shows the decline of pollinators is contributing to the deaths of an estimated half a million people a year worldwide. That’s because yields of nutritious foods like most fruits, vegetables, and nuts are falling as the pollinators they depend on disappear. Dr. Sam Myers, the study’s lead researcher, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss how this falling yield is linked to more preventable deaths from ailments such as heart disease and diabetes. (09:55)

New Exoplanet Revealed

/ Aynsley O’NeillView the page for this story

NASA scientists used data from the James Webb Space Telescope to identify exoplanet LHS 475 b. Exoplanets are planets outside of our solar system that orbit a different star, and can be very difficult to identify. Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill spoke with one of the lead researchers on the project, exoplanet astronomer Kevin Stevenson, about how the finding may help develop a model for identifying planets that are likely to contain life. (08:03)

Heat Pump Challenges

/ Reid FrazierView the page for this story

One of the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions in the US comes from heating buildings. The Biden administration is trying to change that by promoting efficient electric heat pumps. But as the Allegheny Front’s Reid Frazier reports, getting Americans to switch to heat pumps won’t be easy. (06:38)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230310 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Linda Bilmes, Sam Myers, Fred Pearce, Kevin Stevenson

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Reid Frazier

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The White House plans to value ecosystem services now ignored by government accounting.

BLIMES: One whale is worth at least $2 million, because the big whales such as sperm whales and filter feeding baleen whales help sequester carbon by hoarding it in their bodies. And they stockpile tons of it, like swimming trees.

CURWOOD: Also, research shows a worldwide decline in pollinators is reducing the production of fruits nuts and vegetables.

MYERS: We're going to add maybe another 2 billion people to the planet's population. We need to produce a lot more food at the same time that pollinating insects and other pollinating animals are in decline. So it is really concerning.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Nature on the Federal Balance Sheet

Natural capital accounting is the process of calculating the dollar value of services provided by nature such as recreation and clean water. (Photo: Taylor Davis, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The Biden Administration is now working to account for “natural capital” and consider the value of services nature provides when making economic decisions. A standing forest, for example, cleans water, sequesters carbon, and provides critical habitat but often the government doesn’t put a dollar value on trees unless they are cut down and made into paper or lumber. The White House now has a working group that will factor in the monetary value of ecosystem services when looking at the costs and benefits of nature based solutions to address climate change and infrastructure. Linda Bilmes teaches Public Policy and Public Finance at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, and is here to explain the new strategy. Linda, welcome back to Living on Earth!

BILMES: Thank you! Delighted to be back.

BASCOMB: So what exactly is being taken into account here? Can you give us a few examples?

BILMES: Yeah, well, right now, the way we measure economic statistics, is we measure economic assets like buildings and factories and machinery and real estate and inventories and things like that. But we don't measure natural assets. So what the Biden administration has now put in place is, for the first time, a national strategy to develop statistics for measuring natural capital. So if you think about a bank, you want to measure how much goes into the bank, and how much comes out of the bank, as well as the point in time of how much you have in your bank account. Now, we want to do this for the environment. So we measure what are our stocks of natural assets like land and soil and fish, and how much we are adding in terms of protecting them and adding to those stocks and how much we are taking out. I mean, if we're trying to think about what is the value of a natural asset, there are a lot of different ways to think about this. But one of the examples that I thought about is the value of a whale. So we all love whales. But how much is a whale worth in terms of what it contributes to the economy. Well, in fact, one whale is worth at least $2 million dollars.

BASCOMB: Why?

A single large baleen whale, like a humpback whale, has been evaluated as worth $2 million. (Photo: Michael Dawes, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BILMES: Because the big whales such as sperm whales and filter feeding baleen whales help sequester carbon by hoarding it in their bodies, and they stockpile tons of it like swimming trees. And if you put it into quantitative terms, a mature tree absorbs up to 22 kilograms of carbon each year. But a single whale in its lifespan stores about 33 tons of carbon dioxide, which means that one whale does the job of 1500 trees. And then when a whale dies, its carcass sinks to the bottom of the sea and all the carbon that it's stored circulates in the cycle for hundreds of years, so it becomes a literal carbon sink. And in addition to that, whales provide services called the whale pump, which is that they feed on these tiny marine organisms, such as krill or plankton, which return to the surface in their plumes, which are rich in iron and phosphorus and nitrogen, and which are exactly the substances that feed the plankton cycle. And plankton is important because it captures 40% of all the carbon produced worldwide and half of the oxygen in the atmosphere. So in short, if you compare the commercial value of a whale, which, for example, if Iceland sells a whale to Japan, for whale meat, it can net about $136,000. But just the environmental value of whale, apart from the intrinsic value of the fact that we love whales, is at least $2 million. And if you actually use the EPA's new social cost of carbon, it's about $8 million per whale. So the stock of whales in the ocean is worth trillions of dollars.

BASCOMB: Well, that's the thing, how might we go about monetizing something like a whale to you know, make that appear on our balance sheets as a positive thing?

New #analysis: Less than 3% of the world’s land remains ecologically intact. We can begin to tackle the problem by adopting #naturalcapital accounts using environmental accounting frameworks https://t.co/dkz0Olylk8 @HUCEnvironment @harvarden @GreenHarvard pic.twitter.com/Zlry2knZ8G

— Linda Bilmes (@LJBilmes) May 13, 2021

BILMES: So the Biden administration has put in place a national strategy to develop statistics for environmental economic decisions, which is like a 15 year plan, involving 27 different government agencies to try and put in place a framework for doing exactly what you're talking about. And it's a kind of multi-year effort, which involves, first of all, working with the international frameworks that have been developed, there is something called the UN System of Environmental Economic Accounting, which has been developed by the UN. Over the last 20 years, it has been implemented in a number of countries around the world. But the US has never participated in it, to begin tracking the value of environmental economic assets. So this is the first time that we're actually joining up. So this is a kind of framework for integrating a lot of different data sources. You know, data on energy and air emissions and agriculture and ecosystems and so on to produce integrated accounts that give us a sense of what we have, and to treat such assets as actual assets on balance sheets. Now, it's not always possible to monetize the value. It is pretty much possible to count and to document what we have and to document the degradation. I think we are not even capable of understanding all of the inter linkages between assets and ecosystem services and value. We're also trying to create sort of pilot accounts. To some extent, we have to try different approaches and see how they work and test them out in different sectors. So there is an Office of Federal Statistician that is working with the IMF and other statistical organizations to develop eight separate accounts, the land account, air emissions, environmental activities, marine, water, pollinators, forest and urban green space, which will be like the first eight kinds of accounts. So we start looking at what we have, and what the natural capital accounts look like for those things. So just even heading in this direction, and starting to do it is a big, big amount of progress for the United States.

BASCOMB: In your opinion, why is this a good strategy? Why do we need to put a dollar value on our natural resources?

Linda Bilmes is a Senior Lecturer in public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School and author of Valuing our National Parks: America’s Greatest Investment. (Photo: Diana Bowen/NPS)

BILMES: Natural assets, like land and water and plants, underpin the wellbeing of society, they underpin business, they underpin prosperity, and they underpin economic opportunity. And they help counteract the risks to the environment and risks to market that are caused by climate change and nature loss. So all of those things, I think, are long overdue in society. And we also need to bring together many different groups that don't typically work together. We have to bring together accountants, and economists, and scientists, and geologists, and engineers, and many different types of people and types of professions, which are all in the government, but which just, it's very difficult without a big government push to do this organically. So I think the government has got to lead this effort, which will give us a much much better kind of toolkit with which to think about making wise environmental decisions and protecting biodiversity.

BASCOMB: Linda Bilmes is a Daniel Patrick Moynihan Senior Lecturer Chair in public policy and public finance at Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government. Linda, thanks so much for your time today.

BILMES: Thank you so much.

Related links:

- Read the White House’s National Strategy to Develop Statistics for Environmental-Economic Decisions

- The Biden Administration’s Fact Sheet on Environmental Economic Decisions

- Read more on Natural Capital Accounting

- Read Linda Bilmes’ Recent Book “Valuing US National Parks and Programs: America’s Best Investment” from Routledge Imprint

- The International Monetary Fund's Article on the Monetary Value of a Whale

[MUSIC: David “Fathead” Newman with Ray Charles, “Hard Times” on Fathead: Ray Charles Presents David “Fathead” Newman, by Ray Charles, Avid Jazz]

Beyond the Headlines

The United Nations has approved a treaty to protect ocean biodiversity on the high seas. (Photo: Gregory “Slobirdr” Smith, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: On the line now with me from Atlanta, Georgia is Peter Dykstra. Peter's a contributor to Living on Earth who's always looking beyond the headlines for us. What do you see today, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve, we'll start with a little good news, because we always want to tell folks about the good news. After years of going back and forth, members of the United Nations have agreed on a treaty to protect biodiversity on the high seas. It's something that's been tossed around forever. The Law of the Sea Treaty has been out there forever. It was ratified in 1994, but never ratified by the United States of America. Marine biodiversity wasn't something that was even considered back then. But look at all the species that migrate in the ocean, that cross national borders and spend a lot of time on the high seas, where there traditionally has been no effective protection. But marine biodiversity is at the heart of this agreement. This is the first step in putting some major regulation and restriction on what can be done about protecting the oceans.

CURWOOD: That's right, I think the majority of the surface of the ocean is not inside some nation's economic zone or something. The so-called high seas where, for very, very long, there's kind of an 'anything goes' attitude.

DYKSTRA: Right, and there are a lot of things like the improved satellite monitoring of the high seas, where there are areas when you cannot, in any practical way, police the oceans from the oceans. But from a satellite, you can find factory fleets operating illegally to overfish. You could find pirate fishing boats, as they're called, out there to take species and completely ignore their endangered or threatened status. So we're beginning to close these loopholes. There's still a long way to go. But in terms of ocean biodiversity, here's a step forward.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I mean, hopefully the United States will ratify this agreement, because people are more and more aware of how important these protections are. In fact, there's a recent one that, where is it in South America, that's just been declared, Peter.

DYKSTRA: An area called Corcovado Gulf, nearly pristine. Chile has set up something called - and I'm not making this up, this is the name - the Tictoc marine park. It has no relation to children's games or sound effects, or large controversial social media sites. But that's what it's called, the Tictoc marine park. And the thing that's a really big deal is the biggest animal in the world. As much as 10% of the world's blue whale population spends time in Corcovado Gulf. The blue whale is seriously endangered, and 10% of their population is going to get a little bit more protection.

CURWOOD: Well, that is really good news as well. Hey, what else do you have for us today, Peter?

Sea ice levels in Antarctica reached a historic low this year. (Photo: Povl Abrahamsen, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Something from the southern oceans. That is new news. We thought this was the case, now there's confirmation from satellite records and other monitoring that the Antarctic sea ice, not the glaciers on the land base of Antarctica, but the sea ice surrounding the continent reached its lowest levels ever. As much as 90% of the sea ice that used to be there was gone this year. It's a huge shift. And it could have huge impact on the continent itself, as well as access to the fish species, largely unexploited, that are known to exist around Antarctica.

CURWOOD: Yeah, and as I understand it, the Antarctic sea ice helps hold the glaciers that are onshore that are on the land there. Kind of blocks it, keeps it from sliding into the water. But now it's the smallest level ever. I mean, losing this fringe of sea ice might speed up perhaps a rise in world sea levels.

DYKSTRA: That's right, as land-based ice from glaciers and ice shelves continues to melt. That's what threatens places from Miami and lower Manhattan to coastlines around the world. And that sea level rise from land-based ice does have sort of a two step connection to what's going on with sea ice around the Antarctic continent.

CURWOOD: Of course, we're now nearing the end of the summer in the southern hemisphere. In the northern hemisphere where we are, Peter, the ice is lowest in September. So hey, what do you have for us from the annals of history today?

EPA Administrator Anne Gorsuch Burford (right) meets with President Ronald Reagan (left) and White House Cabinet Secretary Craig L. Fuller (back). (Photo: White House Photograph Collection, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: A 40th anniversary of a momentous thing in the history of the US EPA, because on March 9, 1983, Anne Gorsuch Burford, who was President Reagan's EPA Administrator, resigned under fire. She had a very controversial, stormy time at EPA, marked particularly by a scandal over handling money in the Superfund toxic waste program. Gorsuch Burford's number one assistant went to prison for it. Anne Gorsuch Burford avoided prison time, but left under, no pun intended, kind of a toxic cloud.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is a contributor to Living on Earth. Thanks so much, Peter, we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot and we'll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth webpage. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- AP News | “Nations Reach Accord to Protect Marine Life on High Seas”

- Cetacean Specialist Group | “Blue Whales Protected in the Largest Marine Park in Continental Chile”

- The Guardian | “‘Everyone Should Be Concerned’: Antarctic Sea Ice Reaches Lowest Levels Ever Recorded”

- Read Anne Gorscuh Burford’s obituary in the Washington Post

[MUSIC: David “Fathead” Newman with Ray Charles, “Fathead” on Fathead: Ray Charles Presents David “Fathead” Newman, by Ray Charles, Avid Jazz]

BASCOMB: Coming up – how the decline in pollinators is linked to increased human death and disease. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: New Swing Sextet, “Vete Pa Ya” on Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, iLatin Music for Smayra Publishing SAS]

Indonesia Squelching Biodiversity Research

A mother and infant orangutan. The illegal pet trade is a major threat to orangutans in Indonesia, but obstacles to collaboration with scientists make tracking their populations challenging. (Photo: Bob Brewer, Unsplash, Unsplash license)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Indonesia has one of the world’s largest tropical forests and touts itself as a global leader in conservation. But researchers from outside Indonesia say the government is blocking data to assess claimed conservation progress and has canceled visas of scientists who are asking hard questions. And local scientists fear reprisals if they publish data that doesn't fit the government's optimistic narrative. For more, I’m joined now by Fred Pearce, a veteran freelance environmental journalist based in London.

PEARCE: Hi Steve.

CURWOOD: Tell me, how important is Indonesia to this planet in terms of conservation and the sorts of biological diversity it has.

PEARCE: Indonesia is vital. It has more rainforests than anywhere except Brazil and the Democratic Republic of Congo. And it's been deforesting faster than any of them in some recent years. But it also has a number of iconic species; orangutans, most famously, but also their own species of tigers and elephants, which are, you know, in some cases down to their last few dozen. So it matters a lot.

CURWOOD: And today, you're writing about some foreign researchers that feel that they're being hampered by the Indonesian government for the research that they're doing, and in fact, getting thrown out, having their visas cancelled. Give me a brief overview, please, of what's going on.

Indonesian peatland burning. The government has contested research that indicates more peatland burned than the government initially acknowledged. (Photo: Aulia Earlangga, CIFOR. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

PEARCE: Yes, there's been a long tradition of collaboration between Indonesian scientists, biologists, zoologists, and so on, and outside research, sharing data, sharing analysis. Well, this has kind of broken down in the last couple of years because the government–it's rather, kind of, precious about its reputation. The touch point for the latest row was a letter–well, it wasn't a letter, it was an op-ed piece in the Jakarta Post–calling out the Indonesian government, and the environment minister in particular, for making unreasonably optimistic statements about the state of charismatic species, and in particular orangutans. I mean, basically, the minister had said numbers are going up and a bunch of researchers, there were five–there were five of them listed, said um, "No, you're wrong, we believe that the numbers are going down, and, you know, you're messing with the science, you need to think again." The ministry reacted extremely fast to that. A letter went out more or less on the day, as I understand it, telling National Park administrators to ban the five named researchers, it was the exactly same, five same people from their lands, from their parks, and to end all existing collaboration with them, and also to advise the ministry of any other researchers, foreign researchers, who are working in their territories. And of course, this has had a really chilling effect on domestic researchers as well who like the collaboration, who like joint publications, who like sharing data, and indeed, like getting foreign funding, who really feel that it would jeopardize their career if they do collaborate anymore. So they're kind of retreating from this. And, you know, I spoke to a number of domestic researchers who said, "Well, we really can't collaborate anymore."

CURWOOD: What's the risk to conservation of this conflict between the Indonesian government and foreign researchers and the skepticism, I guess, of some domestic researchers?

PEARCE: I think the danger is that if you don't do the good science, you get bad policymaking. So that–it's not just about science, it's about the business of conservation day-to-day. So if you don't know which forests burned, how much they burned, you can't establish exactly why they burned, who might have been responsible for burning, whether it was all down to climate or whether it was all, you know, down to land disputes, or whatever, you can't resolve these issues, and therefore you can't address them and therefore next time, there's going to be more deforestation than there needs to be. So the danger is that everybody backs off. And there is, again, debate is damaged. And the victims are likely to be the endangered species. There's been a dispute about how the government manages or tries to tackle trade in orangutans, in particular, which are sometimes hunted for bushmeat and more often probably are captured for the booming trade in orangutan pets. If the government says that orangutan numbers are going up, everything is going fine, no problem, then you get the situation now, which is that really nobody's doing much about the pet trade because it doesn't like a big issue because the species is doing fine.

Aerial shot of a palm oil plantation. Indonesia is struggling to reconcile its conservation goals with the economic significance of the palm oil and pulp industries. (Photo: Ricky Martin, CIFOR. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: What other areas of conservation that the government is conducting, is getting the same kind of skepticism? What else is now falling under the lens of skepticism?

PEARCE: Well, there was a row a couple of years ago which resulted in one foreign researcher being expelled from the country about how much damage was done by forest fires; there were a lot of forest fires in 2019 as a result of a period of drought and and the way that farmers tend to go in and those times and start setting fires to clear land. So you know, there was a dispute about the numbers. Some aerial studies carried out by a research institute called CIFOR there came up with rather higher figures than the numbers that were being reported by the government. It requires scientists to get together and debate it. So again, we have this problem of, kind of a war of words, a sort of backing off, everybody getting very cross, the government shutting things down. And so at the end of the day, we don't really know how much forest did burn during that fire. And that has repercussions, serious implications for, if you like, preventing that scale of burning during the next drought.

CURWOOD: Of course, for years there's been a lot of concern about the clearing of the land for the palm oil plantations. At the same time, Indonesia says it's a leader in conservation. What's going on along those lines?

Dr. Siti Nurbaya Bakar, Minister of Environment and Forestry in Indonesia. Clashes between the Environment Ministry and foreign researchers have created a chilling effect on the domestic research environment. (Photo: Ricky Martin, CIFOR. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

PEARCE: There are huge tensions in Indonesia about economic development versus conservation and the government is trying to ride both horses, understandably, probably most governments would. Huge areas of rainforest have been taken over in the last half century, both for palm oil–Indonesia is the world's largest producer of palm oil–and also for the huge paper and pulp industry. These are vast industries that have taken over large areas of land. And the government wants to reduce the amount of damage being done by these things. It would like more plantations for the pulp rather than harvesting natural forests. But that too takes land. But it also wants to engage in conservation activity to protect remaining rainforests. I know that Indonesia has been making a case that it is doing good things on the environment, it is working to protect its rainforest; there is still deforestation going on but it has slowed the pace of that. It is not issuing more licenses for deforestation for the land hungry industries. That's good. Unfortunately, an awful lot of licenses still out there that have not been activated yet. So that won't end deforestation. It's also been working to protect and restore wetlands, swamp forests, in particular, in Borneo. So it's been doing some good things. But you know, it's also doing things which are exacerbating many of the issues, the root causes of deforestation.

CURWOOD: The root causes of deforestation?

PEARCE: The root causes of deforestation lie in land hungry economic development. So that may be palm oil and pulp production. But also just simply farming. Well mining is certainly as an issue in Indonesia, but also farming. You're simply putting in roads so that people can travel around, so that people can connect up and get to markets and people in overflowing cities can move into other places. There's the new capitol city being developed as well. And these all take land. And these all make even currently remote areas of rainforest more and more accessible, which raises the risk of there being ultimately been deforested. I'm sure there will be further loss of rainforest, but I also think that they have the skills, ability, and the desire to stop it.

CURWOOD: Veteran environmental journalist Fred Pierce's latest book is called A Trillion Trees. An article about the issue of what's going on in Indonesia was recently published by Yale e360. Fred, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

PEARCE: Thanks, Steve. I enjoyed it.

CURWOOD: We reached out to the Indonesian government for comment but did not hear back in time for our broadcast.

Related links:

- Yale e360 | “Silencing Science: How Indonesia is Censoring Wildlife Research”

- Check out Fred Pearce’s latest book, “A Trillion Trees”

- Read the op-ed featured in the Jakarta Post

- Read Indonesia’s response here

- Learn more about Indonesia’s incredible biodiversity here

[MUSIC: Asian Traditional Music, "Indonesian Traditional Music" on Traditional Asian Music: Chinese, Japenese, Tibeten, Korean, Oriental Shamisen and Shakuhachi, One Earth Music]

The Human Toll of Pollinator Loss

With declining numbers of insects like bees, the yield of pollinator-dependent crops decreases significantly. (Photo: Andreas Trepte, avi-fauna.info, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.5)

BASCOMB: A study conducted by Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health shows the decline in pollinator populations linked to fruit, vegetable and nut production is leading to the deaths of an estimated half a million people a year worldwide. Pollinators such as butterflies, bats and bees are in dramatic decline so farmers are producing smaller amounts of pollinator-dependent crops. Fresh produce and nuts help keep us healthy and decrease the risk of diseases ranging from heart attacks and stroke to type two diabetes. The loss of pollinators is making healthy foods more costly and less available resulting in more deaths from preventable diseases. The lead researcher of the study is Sam Myers, an expert on planetary health at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

MYERS: We found almost half a million people a year are dying. And the relationship is that we need pollinating animals to optimize the yields of what we call pollinator dependent crops. And, in particular, there are a whole groups of foods in our diet, including fruits and vegetables, and nuts, that are really important in protecting us from diseases like heart disease and stroke, and some cancers and diabetes. And when we don't eat as many servings of those foods, we die in higher numbers as a result of those kinds of diseases. And so what we wanted to understand is, how is the lost production of those kinds of foods actually leading to higher mortality and people around the world from those types of diseases?

BASCOMB: And what exactly did you find?

MYERS: It was a little bit complicated because what we needed to do was actually string together the research from four different groups. And so we started with an understanding from our colleagues in pollinator ecology, who had built a whole network of experimental farms around the world on four different continents, over 300 farms, and had actually measured how much of the reduced production, what's called the yield gap, the gap between the best performing farms and the farms they were working on, how much of that gap was because there weren't enough wild pollinators to optimize the crop yields. And they have found consistently, that about a quarter of the yield gap across the world is from not having enough wild pollinators present. We took those numbers and worked with a second group that actually calculated the yield gaps for all pollinator-dependent crops all around the world on five square kilometer grids, so the entire world and all of the food that we produce. And so we calculated the yield gaps of all pollinator-dependent crops, then we asked if those foods had been produced, how would they have entered the global food trade system and how it would have changed the prices. And using what's called a bio econometric model, which is called IMPACT, we actually calculated how those foods would have moved through the food trade system, and who would have purchased and consumed them. And then finally, working with a fourth group, we could calculate if those foods had been consumed by those populations, how would that have changed their risk of mortality from diseases like heart disease, stroke, some cancers, and diabetes? And what would the total additional mortality have been? And that's where we got this number of just under half a million deaths per year.

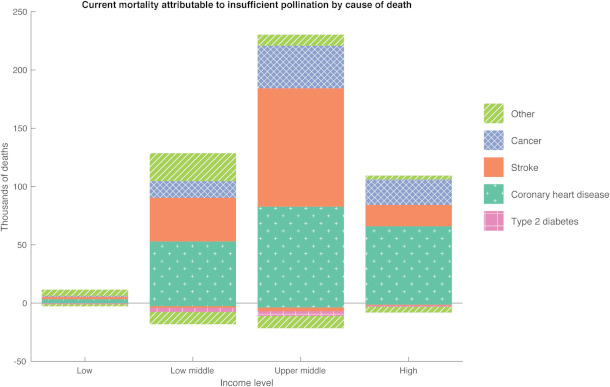

Above is a graph indicating the number of deaths caused by pollinator deficits by income level. Unlike with many environmental issues, those with the lowest income are the least affected while those in the middle-income bracket suffer the most. (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Sam Myers)

BASCOMB: So is this problem of, you know, lack of pollinators and health uniform across the world? Or are you seeing regions where it's specifically concerning?

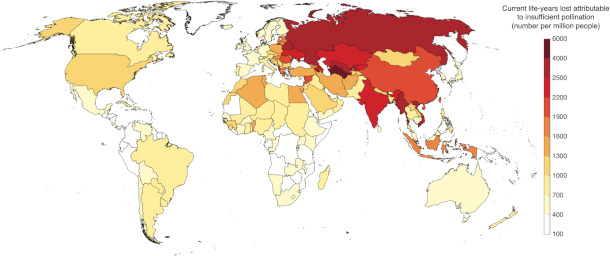

MYERS: You know, the percentage of the yield gap that's being seen on experimental farms on four different continents tends to be pretty robust and uniform that across the board, there's about a 25% of that yield gap is because they're not enough pollinators, how that actually affects the health of different populations and the income for different populations varies enormously by region. And so the greatest vulnerability to the last production of these food groups tends to be in places that already have high prevalence of these diseases like heart disease and stroke, which is primarily the more developed countries with more sedentary lifestyles that are already transitioning to these metabolic diseases, and that are not so wealthy that they can overcome increased prices for these foods by just, you know, paying more money. And so we saw a lot of vulnerability in parts of Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Republic, parts of China. And of course, within every national population, including the United States, there are certainly people who fit that category of having high risk of these diseases but not enough income to be able to overcome higher prices of these food groups.

BASCOMB: You know, usually when we talk about these types of issues, it's the most low income communities that are often disproportionately affected by environmental problems. But it seems like that's not quite the case here.

This map of years of life lost that can be attributed to pollinator deficits displays that it is middle income countries that are the most affected. (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Sam Myers)

MYERS: No, and this was similar to a finding we had in a paper we wrote in The Lancet in 2015, where we saw a very similar sort of at-risk population that was sort of middle income because the diseases that are affected by not consuming pollinator dependent crops are diseases like heart disease and stroke, which actually are less prevalent in the lowest income countries and more prevalent in these middle income countries. And so, yes, you're right, this sort of defies the usual pattern of the greatest vulnerability being among the very poorest populations in the world, and instead, we're finding vulnerable populations in wealthier countries.

BASCOMB: Well, generally, how are farmers responding to the reduced yield in their crops from this loss of pollinators? And I understand that that may be different in different places. But generally speaking, what are you seeing there?

MYERS: Well, the opportunity to respond is what's really exciting. You know, and it's probably worth saying that not only is there this big nutritional challenge associated with insufficient pollinators, but there's a big economic challenge associated. And so we actually looked at a few case study countries, Nepal, Honduras, and Nigeria, and showed that between 13 and 30% of the entire agricultural GDP of those countries was being lost due to insufficient pollination. So this is this free service, right? It's the bees and the ants and the butterflies that are living nearby that are providing a free service that increases the yield of these crops. And when they're not present, the farmers see a real loss in their total income. In terms of what they can do, there's actually really strong consensus among the pollinator ecology community that there's a suite of what are called pollinator-friendly practices, things like planting hedgerows around your farm or intercropping, you know, other species between the crops that you're growing in a field or reducing your use of pesticides, particularly neonicotinoid pesticides, which are really hard on insect pollinators, all of which have been shown to have a real positive impact on improving pollinator populations. And they've also been shown to pay for themselves. So even though you have to take a little bit of land for the hedgerows, or for the intercropping, because you increase the yields on the remaining land, it actually pays for itself quite well. So from a policy standpoint, it would make all kinds of sense for countries to actually institute these pollinator-friendly practices as a way of bringing back these populations. Of course, it would also help the biodiversity crisis sort of writ large by providing habitat and forage for other animals that were losing in high numbers.

Without access to foods like fruits, vegetables, and nuts, people are at a much higher risk of getting chronic diseases such as diabetes. (Photo: picryl, public domain)

BASCOMB: It seems though, that farmers would need a lot of support to be able to implement those strategies versus, you know, if you don't have that support, and you're just a farmer, your yield has dropped, maybe you just need to clear more land. I wonder to what degree are farmers, you know, just taking that approach, because that's what they've done in the past when yields are low?

MYERS: Well, it's a great point. And I think they do need support, not so much financial support, because as I said, within two or three years, these practices tend to pay for themselves, they may need a little bit of support as for the initial investment, but more than anything, they need sort of agricultural extension kinds of support to understand what the practices are, and how to actually institute them. You know, when we look sort of toward the future, and we think about the fact that we're going to add maybe another 2 billion people to the planet's population, we need to produce a lot more food at the same time that pollinating insects and other pollinating animals are actually in decline. So the two trends are sort of going in the opposite direction. It is really concerning in terms of that trend. And if we think about well, so how do we maintain adequate supply of things like fruits and vegetables and nuts, if we don't have pollinators, then our only opportunity is going to be what we call agricultural extensification meaning we have to clear more land, which has more impact on biodiversity, use more agrochemicals, more water, more fossil fuel. And so the ecological impact of replacing pollinators with these other approaches is actually quite enormous. And that's what's so interesting to me is there's this sort of nexus of health effects, economic effects, and environmental effects, all of which point to the real importance of instituting these pollinator friendly practices on farms around the world.

BASCOMB: Sam Myers is a principal research scientist at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. Dr. Meyers, thank you so much for your time today.

MYERS: It was great to be with you. Thank you.

Related links:

- Learn more about the decline of insect populations around the world

- Read the full study

[MUSIC: David “Fathead” Newman with Ray Charles, “Weird Beard” on Fathead: Ray Charles Presents David “Fathead” Newman, by Ray Charles, Avid Jazz]

CURWOOD: Coming up – How heat pumps can comfortably heat and cool homes with a fraction of the greenhouse gas emissions. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “Rhythm of the Desert” on Southwest, by Eric Tingstad, Cheshire Records]

New Exoplanet Revealed

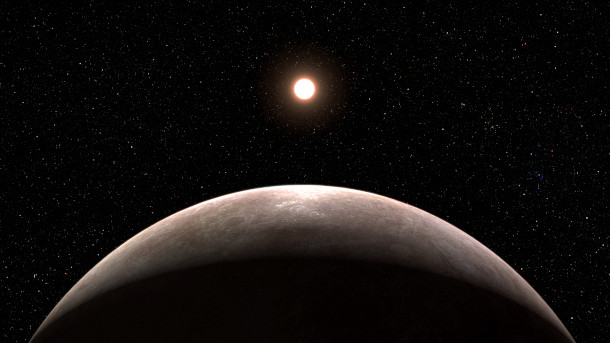

An illustration of LHS 475 b. Scientists are determining whether the newly discovered exoplanet has an atmosphere. (Photo: NASA/European Space Agency/Canadian Space Agency/L. Hustak (STScI))

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

NASA’s James Webb Space telescope has been amazing scientists since it became fully operational last summer. It’s collected beautiful images of nebulas and the distant past, forcing researchers to reconsider how early galaxies developed. And in mid-January, scientists used the telescope to identify exoplanet LHS 475 b. Researchers hope the discovery will help them develop a model for identifying planets that are likely to contain life. For more, we reached out to one of the lead researchers on the project, Kevin Stevenson, he’s an exoplanet Astronomer at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, and spoke with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill.

O'NEILL: Now, what is an exoplanet and what makes them so interesting to study?

STEVENSON: An exoplanet is really just a planet like we understand in our own solar system. But it just so happens to be orbiting another star. So, you know, there are billions of stars in our galaxy. And there are in fact, billions upon billions of planets around those stars. And so it's really just any planet could be big or small, hot or cold, that is out there, orbiting around these other stars, minding their own business having a great time.

O'NEILL: And can you tell me a little bit about the discovery of this new exoplanet LHS 475 b?

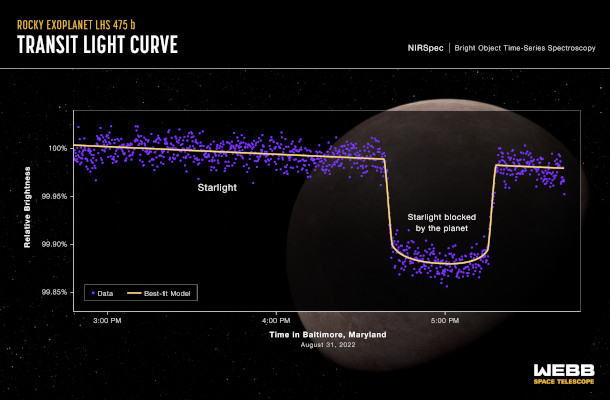

STEVENSON: Yeah, this planet was actually originally a planet candidate. And so it was first detected, at least initially using the TESS observatory. Now, TESS is another NASA mission that has been flying for the past several years, and its primary goal is to search for transiting exoplanets like this one. Now, at the time, it was not confirmed it was what we call a planet candidate. So there had been no follow up observations to validate this as a an Earth-sized rocky planet. And this is where the James Webb Space Telescope really comes into play. We were able to use observations from this new telescope that has large collecting, area broad wavelength coverage, just a fantastic telescope, in order to measure the transit depth of this planet and in fact confirm that it is a planet and not some other false positive signal.

This graph shows the change in brightness of LHS 475 b over time. This data indicates the planet’s size and distance from its star, but not whether it has an atmosphere. (Photo: NASA/European Space Agency/Canadian Space Agency/STScI/L. Hustak (STScI)/Johns Hopkins APL)

O'NEILL: And why is the planet's name LHS 475 b, and for that matter, is there any chance it'll get a colloquial name, so we don't have to keep saying LHS 475 b?

STEVENSON: LHS signifies the survey that it comes from. There are several different surveys that have been conducted, so this particular system actually has multiple names. It just so happens that LHS is probably the first survey, from what we can tell, that actually identified this star as being a nearby M dwarf. So that's what we picked and it is 475 it is the 4705th star in the survey. Now, typically when we name planets, we use B, C, D, E, F, the letters of the alphabet, because A is the primary the star itself. The first planet is B because the star is always A. We do have a nickname for this planet. Some of the students and postdocs in our group are big Taylor Swift Fans, so they labeled it Swifty one b.

O'NEILL: Oh, that's excellent. Oh, Has anyone told her about it?

STEVENSON: I don't think so. This will be news to her.

O'NEILL: Well, based on what we've learned so far about the planet, what are scientists saying? LHS 475 b is like? Is it a rocky planet like Earth? A gas giant like Jupiter? And what are the chances that it might possibly be habitable?

STEVENSON: Well, that's a great question, because based off of what we understand the star is, is an M dwarf, and it's quite small. And that means that we're sensitive to small planets like this one. So just first off, we would never have detected this planet if it were orbiting a sun-like star. And from what we can measure about the size of the signal, we can tell you that the planet is .99x the size of the Earth. But that doesn't mean it's the same temperature. And that does not mean it's habitable. So based off of what we can determine, it's probably closer to 500 degrees Fahrenheit. So a lot hotter. And so chances are a lot of the water has boiled away on this planet. And it could be something like Mars, for example, where it has no or tenuous atmosphere. But this planet could also be like Venus, where it has a high altitude cloud deck with a thick atmosphere, it's really difficult to tell the difference between those two based off of the observations that we've made here, but it is tantalizing to consider the possibilities.

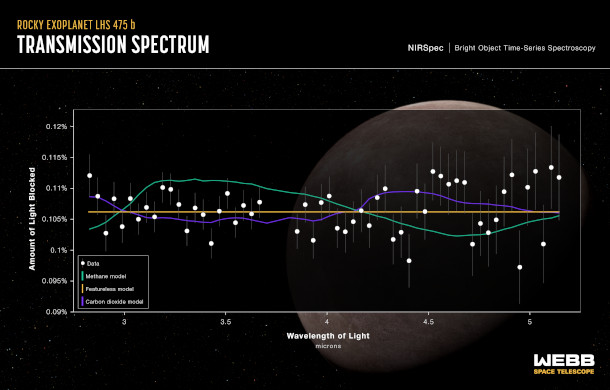

With current data, scientists can’t determine whether LHS 475 b has no atmosphere, an atmosphere made of carbon dioxide, or an atmosphere made of methane. Current data indicates the flatline seen on the graph: wavelengths of light that signify no atmosphere. But with more precision, researchers could see wavelengths indicating the methane model (the green line) or the carbon dioxide model (the purple line). (Photo: NASA/European Space Agency/Canadian Space Agency/STScI/L. Hustak (STScI)/Johns Hopkins APL)

O'NEILL: So how much can be learned from the current James Webb space telescope data on this planet, and how much will need more investigation?

STEVENSON: Right now we have to transit observations of LHS 75 B. From that we can place basic constraints on its atmospheric composition, we do know that the planet doesn't have a giant ball of hydrogen helium atmosphere, like Jupiter or Saturn, Uranus, Neptune. We also know that the planet probably doesn't have a pure methane atmosphere, or something similar to Titan. Now, things get a little bit more confusing when you start considering planets like Venus and Mars, both of which have carbon dioxide, CO2, as their main constituent in their atmosphere, but they're very, very different in terms of the atmospheric pressure. Venus has a lot of atmosphere, where Mars does not. And we can't really differentiate between those two scenarios just yet with the data. So we're looking to have follow on observations, we're going to be getting a new transit observation in the summer of 2023. And we also hope to get a secondary Eclipse observation, this is where the planet passes in behind the star. And from that, we can actually differentiate between our two scenarios, the Venus scenario and the Mars scenario, because a planet with a thick atmosphere is going to have a very shallow Eclipse depths, so very weak signal. Whereas a planet like Mars that essentially has no atmosphere, is going to have a very bright secondary Eclipse measurement. So using these two observations, the transit and the Eclipse, we're going to be able to learn a lot about this planet.

O'NEILL: And what's the importance of figuring out if the planet has an atmosphere? Is it sheer scientific curiosity? Or is it likely to reveal something else about our universe?

STEVENSON: Well, part of this program we have is to observe multiple planets all orbiting M dwarf stars. And what we're trying to determine is whether or not there is a universal divide between planets with and without atmospheres. And this is what we call the cosmic shoreline. The idea is that we want to be able to predict which planets have atmospheres and which ones don't, before investing a huge amount of telescope time into searching for signs of life. And the idea here is that if we can use basic information about the planet, and from that, if we can ascertain whether or not this plant has an atmosphere or not, then we can focus our observations in the future on only those plants that have atmospheres. So there is a long sort of process of trying to find life on other worlds. And it starts with answering the very basic question of which planets have atmospheres and which ones don't. So we're trying to start the first step towards the search for life. And this is the first planet in our program.

CURWOOD: Kevin Stephenson is an exoplanet astronomer at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neil

Related links:

- More information about LHS 475 b and its location

- What’s an exoplanet?

- Learn more about the James Webb Space Telescope

[MUSIC: Alexander Courage, Gerald Fried, Bob Harlan “Star Trek – The Motion Picture: Main Title” on Boston Pops Orchestra: John Williams, UMG Recordings]

Heat Pump Challenges

Brendon Slotterback had a contractor install a heat pump outside his Pittsburgh home. (Photo: Reid R. Frazier from The Allegheny Front)

BASCOMB: One of the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions in the US comes from heating buildings. The Biden administration is trying to change that by promoting efficient electric heat pumps. But as the Allegheny Front’s Reid Frazier reports, getting Americans to switch to heat pumps won’t be easy.

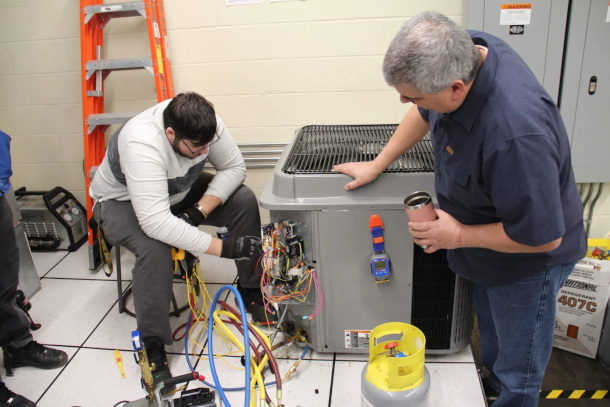

FRAZIER: Jason Nadzam is standing in a workshop at the Community College of Allegheny County in the western suburbs of Pittsburgh. He's teaching a class on HBC, that's heating, ventilation and air conditioning. Today he's giving a demonstration to the students. He flips on a heat pump, basically a machine that looks like an air conditioner.

NADZAM: So you can hear all instead of this thing just firing on the start cap and the contact potential relays like a conventional motor would. This thing ramps up, so it's an inverter that is ramping up the frequency.

FRAZIER: Heat pumps have been around for years, but many now see them as crucial in the fight to slow global warming. To Nadzam, they're also a way to lower home heating bills.

NADZAM: You look at the price of what home heating oil is right now. You're looking at $5 a gallon to fill a thousand gallon tank to get you through winter. That's a that's a big pill to swallow. So that's where a heat pump would be beneficial.

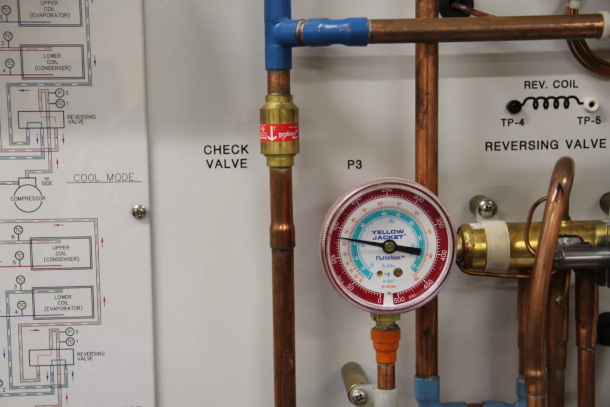

FRAZIER: When it comes to carbon dioxide pollution, the main cause of climate change. Heat pumps have two advantages over fossil fuels like natural gas, propane and heating oil. One is they use electricity, so it's possible to run them on zero carbon sources like wind, solar and nuclear. The other is they're very efficient. Amy Boyd is with the Acadia Center in Boston, which helps northeastern states meet climate targets. She says heat pumps work so well because they're not generating heat like a furnace or stove. Instead, they rely on a clever piece of technology called a heat exchanger.

Jason Nadzam (right) and student DJ Eversole, 18, troubleshoot a heat pump at an HVAC class at Community College of Allegheny County. (Photo: Reid R. Frazier from The Allegheny Front)

BOYD: The way that heat pumps work is they move heat. And so even if it seems cold to your eye, if it's any warmer than the vacuum of space, then there is heat out there to be moved.

FRAZIER: Because it's only moving heat around, not creating it. Heat pumps are up to four times more efficient than a standard furnace. In the summer, they can reverse themselves, doubling as air conditioners. Right now, about 10% of homes in the U.S. use heat pumps. That number will have to go up if the country is going to meet its climate goals.

BOYD: Eliminating the greenhouse gas emissions that are coming from our heat, particularly in the Northeast, is one of the biggest things that an individual consumer can do to fight climate change.

FRAZIER: Buildings are second only to transportation as sources for greenhouse gases. In Pittsburgh, around a quarter of the city's greenhouse gas emissions come from heating buildings with natural gas. But there are downsides to heat pumps. They get less efficient, the colder it gets. That's why they're more common in southern, warmer states. And they may cost more to run than gas furnaces. That's because electricity is usually more expensive than natural gas, which heats about two thirds of homes in Pennsylvania. Nadzam found this out when he installed a heat pump in his own house 20 years ago, taking advantage of a special rate from a local electric utility a few years ago. The utility ended the special rate.

NADZAM: All of a sudden, my electric bills skyrocketed because when we go below 30 or 25, that electric resistance heats coming on. And now the meter's flying. It's smoking.

A demonstration heat pump in Jason Nadzam’s HVAC class at Community College of Allegheny County. (Photo: Reid R. Frazier from The Allegheny Front)

FRAZIER: He replaced his old heat pump with a new one that works better in colder temperatures. As a result, his electric bill has gone down.

NADZAM: It's a 1982 color supreme versus a Prius. There's no comparison.

FRAZIER: But many contractors, especially in cold cities like Pittsburgh, are reluctant to recommend heat pumps to customers. In a basement in Pittsburgh's belts Hoover neighborhood, Chino Ottoviani cuts out a pane of sheet metal from a new gas furnace. He's hooking up today. The customer's heat has been out for several days.

OTTOVIANI: This a 70,000 BTU natural gas furnace cut in the return area and on the side.

FRAZIER: The woman that lives here called a few days ago. Her furnace, over 40 years old, had stopped working. Ottoviani recommended the cheapest and simplest repair, a furnace replacement for around $6,000. He did not steer the customer to a heat pump, in part because the house didn't already have central air conditioning.

OTTOVIANI: Then we could have that conversation of, hey, if you're going to replace this instead of just AC only, would you like a heat pump? But it's it we just needed to get her up and running.

FRAZIER: Adding an electric heat pump on top of the gas furnace would be one solution. That way, the gas furnace could run only on the coldest days, but that would have cost 6 to $8000 extra.

OTTOVIANI: Financing. 6000 versus financing 12,000. Kind of a it's a big difference for people. And a lot of people, believe it or not, don't care about that furnace at all until it doesn't work.

Contractor Gino Ottoviani installs a natural gas furnace in a Pittsburgh basement. He didn’t recommend a heat pump because of the added expense. (Photo: Reid R. Frazier from The Allegheny Front)

FRAZIER: The Biden administration is trying to make heat pumps more affordable through a series of tax breaks. The Inflation Reduction Act, passed last year includes extra incentives for low income households to get heat pumps and other energy efficiency upgrades. But contractors are not always happy to install heat pumps. When he tried to find one that did, Brendan Slotterback back encountered resistance. The first one he talked to listed several reasons not to do it.

SLOTTERBACK: Like, well, that's going to it's not really going to work and it's going to be more expensive. And so, I just I want, I knew that that was not true, just given, you know, folks that I talked to who work on this every day.

FRAZIER: Slotterback and his wife Clarissa, both work in the sustainability field. They eventually found a contractor that would install a heat pump. Their gas furnace remains in place to run when the weather gets really cold, like it did this Christmas. In his yard, the heat pump sits innocuously next to his house where the air conditioner once stood.

SLOTTERBACK: Basically, the unit they took out of there looked almost exactly the same. This one's maybe like six inches taller.

FRAZIER: Slotterback back says his heating costs overall are about the same as before, but he's using much less natural gas. He buys electricity from a clean energy supplier, so he's heating his home on an extreme carbon diet. I'm Reid Frazier.

BASCOMB: That story comes to us courtesy of the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Allegheny Front | “The Modest Heat Pump Could be a Climate Solution, but Getting them into Houses will be Hard”

- Learn more about the Inflation Reduction Act and Energy Costs

[MUSIC: David “Fathead” Newman with Ray Charles, “Mean to Me” on Fathead: Ray Charles Presents David “Fathead” Newman, by Ray Charles, Avid Jazz]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth you can hear a conversation with primatologist and activist Jane Goodall on her time studying chimps in Tanzania.

[MUSIC: David “Fathead” Newman with Ray Charles, “Mean to Me” on Fathead: Ray Charles Presents David “Fathead” Newman, by Ray Charles, Avid Jazz]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Fern Alling, Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Jusneel Mahal, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth