Heat Pump Challenges

Air Date: Week of March 10, 2023

Brendon Slotterback had a contractor install a heat pump outside his Pittsburgh home. (Photo: Reid R. Frazier from The Allegheny Front)

One of the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions in the US comes from heating buildings. The Biden administration is trying to change that by promoting efficient electric heat pumps. But as the Allegheny Front’s Reid Frazier reports, getting Americans to switch to heat pumps won’t be easy.

Transcript

BASCOMB: One of the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions in the US comes from heating buildings. The Biden administration is trying to change that by promoting efficient electric heat pumps. But as the Allegheny Front’s Reid Frazier reports, getting Americans to switch to heat pumps won’t be easy.

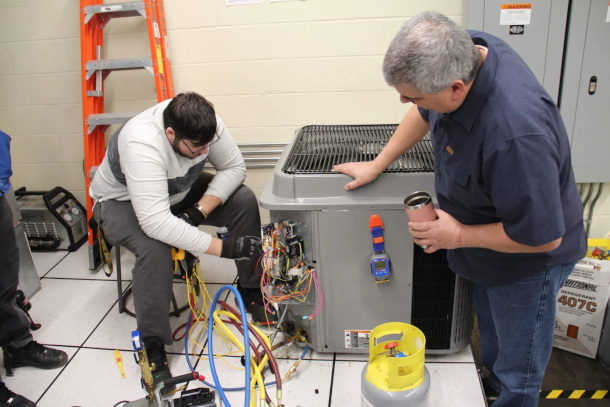

FRAZIER: Jason Nadzam is standing in a workshop at the Community College of Allegheny County in the western suburbs of Pittsburgh. He's teaching a class on HBC, that's heating, ventilation and air conditioning. Today he's giving a demonstration to the students. He flips on a heat pump, basically a machine that looks like an air conditioner.

NADZAM: So you can hear all instead of this thing just firing on the start cap and the contact potential relays like a conventional motor would. This thing ramps up, so it's an inverter that is ramping up the frequency.

FRAZIER: Heat pumps have been around for years, but many now see them as crucial in the fight to slow global warming. To Nadzam, they're also a way to lower home heating bills.

NADZAM: You look at the price of what home heating oil is right now. You're looking at $5 a gallon to fill a thousand gallon tank to get you through winter. That's a that's a big pill to swallow. So that's where a heat pump would be beneficial.

FRAZIER: When it comes to carbon dioxide pollution, the main cause of climate change. Heat pumps have two advantages over fossil fuels like natural gas, propane and heating oil. One is they use electricity, so it's possible to run them on zero carbon sources like wind, solar and nuclear. The other is they're very efficient. Amy Boyd is with the Acadia Center in Boston, which helps northeastern states meet climate targets. She says heat pumps work so well because they're not generating heat like a furnace or stove. Instead, they rely on a clever piece of technology called a heat exchanger.

Jason Nadzam (right) and student DJ Eversole, 18, troubleshoot a heat pump at an HVAC class at Community College of Allegheny County. (Photo: Reid R. Frazier from The Allegheny Front)

BOYD: The way that heat pumps work is they move heat. And so even if it seems cold to your eye, if it's any warmer than the vacuum of space, then there is heat out there to be moved.

FRAZIER: Because it's only moving heat around, not creating it. Heat pumps are up to four times more efficient than a standard furnace. In the summer, they can reverse themselves, doubling as air conditioners. Right now, about 10% of homes in the U.S. use heat pumps. That number will have to go up if the country is going to meet its climate goals.

BOYD: Eliminating the greenhouse gas emissions that are coming from our heat, particularly in the Northeast, is one of the biggest things that an individual consumer can do to fight climate change.

FRAZIER: Buildings are second only to transportation as sources for greenhouse gases. In Pittsburgh, around a quarter of the city's greenhouse gas emissions come from heating buildings with natural gas. But there are downsides to heat pumps. They get less efficient, the colder it gets. That's why they're more common in southern, warmer states. And they may cost more to run than gas furnaces. That's because electricity is usually more expensive than natural gas, which heats about two thirds of homes in Pennsylvania. Nadzam found this out when he installed a heat pump in his own house 20 years ago, taking advantage of a special rate from a local electric utility a few years ago. The utility ended the special rate.

NADZAM: All of a sudden, my electric bills skyrocketed because when we go below 30 or 25, that electric resistance heats coming on. And now the meter's flying. It's smoking.

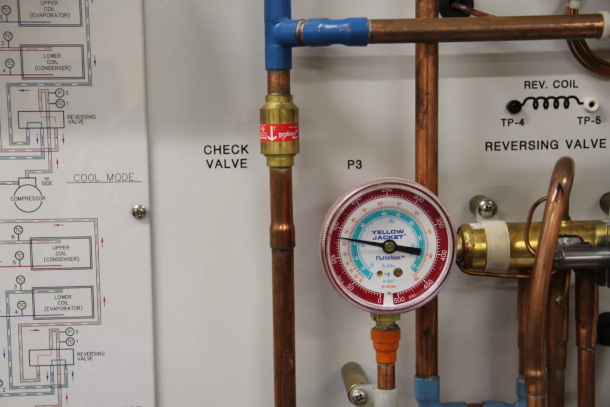

A demonstration heat pump in Jason Nadzam’s HVAC class at Community College of Allegheny County. (Photo: Reid R. Frazier from The Allegheny Front)

FRAZIER: He replaced his old heat pump with a new one that works better in colder temperatures. As a result, his electric bill has gone down.

NADZAM: It's a 1982 color supreme versus a Prius. There's no comparison.

FRAZIER: But many contractors, especially in cold cities like Pittsburgh, are reluctant to recommend heat pumps to customers. In a basement in Pittsburgh's belts Hoover neighborhood, Chino Ottoviani cuts out a pane of sheet metal from a new gas furnace. He's hooking up today. The customer's heat has been out for several days.

OTTOVIANI: This a 70,000 BTU natural gas furnace cut in the return area and on the side.

FRAZIER: The woman that lives here called a few days ago. Her furnace, over 40 years old, had stopped working. Ottoviani recommended the cheapest and simplest repair, a furnace replacement for around $6,000. He did not steer the customer to a heat pump, in part because the house didn't already have central air conditioning.

OTTOVIANI: Then we could have that conversation of, hey, if you're going to replace this instead of just AC only, would you like a heat pump? But it's it we just needed to get her up and running.

FRAZIER: Adding an electric heat pump on top of the gas furnace would be one solution. That way, the gas furnace could run only on the coldest days, but that would have cost 6 to $8000 extra.

OTTOVIANI: Financing. 6000 versus financing 12,000. Kind of a it's a big difference for people. And a lot of people, believe it or not, don't care about that furnace at all until it doesn't work.

Contractor Gino Ottoviani installs a natural gas furnace in a Pittsburgh basement. He didn’t recommend a heat pump because of the added expense. (Photo: Reid R. Frazier from The Allegheny Front)

FRAZIER: The Biden administration is trying to make heat pumps more affordable through a series of tax breaks. The Inflation Reduction Act, passed last year includes extra incentives for low income households to get heat pumps and other energy efficiency upgrades. But contractors are not always happy to install heat pumps. When he tried to find one that did, Brendan Slotterback back encountered resistance. The first one he talked to listed several reasons not to do it.

SLOTTERBACK: Like, well, that's going to it's not really going to work and it's going to be more expensive. And so, I just I want, I knew that that was not true, just given, you know, folks that I talked to who work on this every day.

FRAZIER: Slotterback and his wife Clarissa, both work in the sustainability field. They eventually found a contractor that would install a heat pump. Their gas furnace remains in place to run when the weather gets really cold, like it did this Christmas. In his yard, the heat pump sits innocuously next to his house where the air conditioner once stood.

SLOTTERBACK: Basically, the unit they took out of there looked almost exactly the same. This one's maybe like six inches taller.

FRAZIER: Slotterback back says his heating costs overall are about the same as before, but he's using much less natural gas. He buys electricity from a clean energy supplier, so he's heating his home on an extreme carbon diet. I'm Reid Frazier.

BASCOMB: That story comes to us courtesy of the Allegheny Front.

Links

Learn more about the Inflation Reduction Act and Energy Costs

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth