Oceans Hotter Than Ever

Air Date: Week of May 5, 2023

In the last 5 years, the global ocean surface heat content has raised by almost a full degree Fahrenheit. (Photo: Riccardo Maria Mantero, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The average sea surface temperature of the world’s oceans is rising as the planet warms and global temperatures recently hit all-time highs. Now the La Niña weather pattern of the last 3 years is shifting to an El Niño cycle, warming the oceans even more. Kevin Trenberth is a Distinguished Scholar at the National Center of Atmospheric Research and joins Host Bobby Bascomb to explain why the rapid warming of the oceans puts the whole Earth at risk.

Transcript

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The world’s oceans store nearly 90 percent of the excess heat produced from anthropogenic climate change and they are warming at an alarming rate. According to NOAA data the average sea surface temperature hit an all-time high last month. In just 5 years the global ocean heat content has increased by .07 degrees Fahrenheit. That may not sound like much but it’s roughly 30 to 40 zettajoules of heat, or equivalent to hundreds of millions of atomic bombs like that one that destroyed Hiroshima. And now, amid rising ocean temperatures, the Pacific Ocean is also moving away from a La Nina weather event and towards El Nino, which will cause sea surface temperatures to be warmer still. For more I’m joined now by Kevin Trenberth, a Distinguished Scholar at the National Center of Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. Welcome back to Living on Earth!

TRENBERTH: Oh, thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: So NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recently informed us that we seem to be heading out of our La Niña weather event and moving towards El Niño. What exactly does that transition likely look like? You know, what can we expect to see in the next year or so?

TRENBERTH: The last three years, we've been in this thing called the La Niña, which means it's quite cold along the Tropical Pacific from the dateline to the Americas over an extensive region. That's a region larger than the area of the United States. And so this has kept sea surface temperatures at relatively low levels. But that has changed this year. And so there is evidence that an El Niño could well be beginning and there's certainly a coastal El Niño along the coast of South America that's occurring already. And so temperatures have risen quite sharply there. And that has local effects, changing the rainfall and the weather patterns in that region and changing the fisheries. And the anticipation is at the moment that this is likely to become more widespread. So it becomes a basin wide El Niño event later this year, following an El Nño event, there's more heat that comes out of the ocean into the atmosphere. And that warms the atmosphere. And so the prospects are that certainly 2023 will be a bit warmer than it has been because of the cold sea temperatures in the tropical Pacific in the past three years. But 2024 could well break a new record and create the highest global mean surface temperature year on record. That's the expectation at the moment.

BASCOMB: And how does climate change affect what you might expect to see from a typical El Niño or La Niña pattern? You know, it's supercharged so many things in our weather, what do you expect to see in terms of how climate change will impact these weather systems?

TRENBERTH: Climate change, the increase in heating from increasing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, most of that heat ends up in the ocean. And so the oceans are expanding, the sea level is higher, the sea temperatures as a result are potentially higher, unless something like an La Niña suppresses that. And now that the La Niña is over with, all of that warmth is coming. So what we're really seeing, in some ways, is an El Niño supercharged by global warming. Now what that does in the atmosphere is it creates more evaporation into the atmosphere that warms and moistens. The atmosphere invigorates all of the storms, especially in the Pacific region, all of the typhoons and tropical cyclones and the sorts of things actually we've seen recently in California with these atmospheric rivers coming into California causing tremendous amounts of rainfall. And then the potential for flooding. And so this is one of the prospects is that we have more active weather events, but they occur in different places than they have done over the last two or three years.

BASCOMB: Scientists have also told us that they're recording an abnormal acceleration of ocean temperatures, you know, warming much more than they might expect. How does that compare to what you would normally expect in an El Niño event, you know, when the weather's shifting, and how much of that is due, you know, simply to climate change?

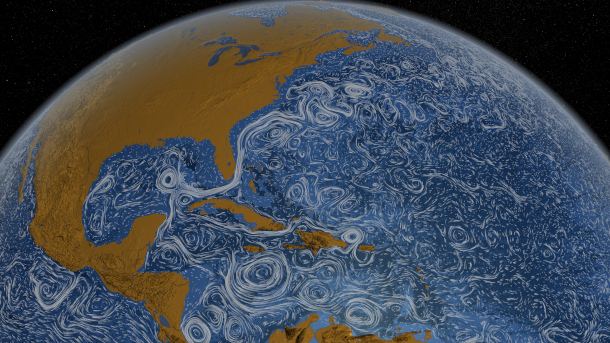

A timelapse image of ocean currents between June 2005 and December 2007 showcases the Gulf Stream in the thick line along the southeast coast of the United States. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

TRENBERTH: So we've written annual papers, my colleagues and I, over the last several years, and in January republished the assessment for 2022. And 2022, was the warmest year on record for the global oceans. 2021 was the warmest year before that. Now, this is looking at ocean heat content, it's not just looking at the surface, but the top 2000 meters of the ocean. And we have pretty good measurements of that now. And so the oceans are certainly warming. And that shows better than anything else, actually, the global warming signature. Now we've got these conditions with the change in the La Niña to El Niño and the Tropical Pacific. And so all of this is coming out now at the surface. And so the sea surface temperatures are now the highest on record. March is when the sea temperatures are normally highest. And that's because that's the equinox in the southern hemisphere, and the smaller ocean in the southern hemisphere. And so the southern hemisphere controls the overall ocean temperatures in that sense. And what we've seen just in the last month or so, is extraordinary. We've never seen sea surface temperatures this high before and certainly going in a rather different direction than all previous years. So normally, the global sea surface temperatures are beginning to cool off at this time and it hasn't happened so much this year. So this is indeed an indication that, you know, global warming is rearing its head and manifesting itself in part as this El Nino event.

BASCOMB: And what about ocean currents? You know, things like the Gulf Stream, how might those systems might be affected by increased ocean temperatures?

Even an end to human-based greenhouse gas emissions will not prevent sea level rise, as much is already “baked in”. (Photo: Geoff Whalan, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

TRENBERTH: Yeah, so that's a very good question. And it's a little hard to tell, the Gulf Stream is a part of a larger, what we refer to as Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. So it's actually goes all the way from the southern hemisphere, right up into the northern parts of the Atlantic. And it is very much affected by the amount of heat that comes into and out of the oceans. And so the prospects there are, indeed, that there can be changes in the Gulf Stream. And this has consequences for further up in the North Atlantic. In general, it's expected that the North Atlantic might not warm quite as much as some other regions, partly because of changes in the Gulf Stream, and this Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, but it still warms. And so it's a little hard to know, overall, exactly how this is gonna play out?

BASCOMB: Well, maybe this is an unanswerable question. But is there you know, a limited capacity to how much the oceans can do in terms of storing excess heat and carbon?

TRENBERTH: The oceans are quite cold at the bottom of the oceans. And there is a strong gradient in temperature called the thermocline, as we go to the top part of the ocean, so the top of the ocean is much warmer than the oceans in general. And if we put more heat in, then that increases the stratification in the ocean. And this does tend to slow down the exchanges of heat and gases, oxygen and carbon dioxide into the ocean. And so it does slow down the uptake of heat and carbon dioxide. But nonetheless, the warmer the top part of the ocean means it's more out of equilibrium with the bottom part of the ocean. And so the ocean, even if we stop global warming altogether, so called net zero, the oceans keep warming for decades and even centuries into the future. And so sea level rise goes along with that continues. So even if we begin to stop global warming, from the standpoint of the heating, the imbalance in the oceans means that they are still slowly responding. But the response does get slowed down by the fact that the ocean has become more stable. So I don't know that we've passed a particular threshold at the moment. But you know, what can indeed happen is the sort of thing we were talking about a couple of minutes ago, with a change in the track of the Gulfstream, for instance. And so big changes like that may not be easily reversible. Other changes, like melting of Greenland, if we melt Greenland, you can't put that water back in the form of a great big ice block again, readily. And so those changes are irreversible. And those are the sorts of things that mean that the future climate is simply going to be different than it has been in the past.

Kevin Trenberth is a distinguished senior scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research, a lead author for three IPCC assessments and a leading expert on the El Niño Southern Oscillation. (Photo: National Center for Atmospheric Research)

BASCOMB: To what degree are you hopeful or optimistic that we can get a handle on this, you know, massive problem that we've put ourselves into?

TRENBERTH: Well, I have moved to New Zealand. Maybe that's this, that's one of the factors actually, although New Zealand has got a you know, a lot of coastal problems and erosion, but is less likely to be affected by the global climate change than a number of other areas. And so the droughts and the floods in various places and the need to actually plan for those and build resilience where we can, and not enough of that is happening in the United States or in other places around the world. And so, you know, we could do a lot better.

BASCOMB: Kevin Trenberth is a distinguished scholar at the National Center of Atmospheric Research. Kevin, thank you so much for your time today.

TRENBERTH: Oh, you're most welcome.

Links

CNN | "La Niña Has Ended and El Niño Will Form During Hurricane Season, Forecasters Say"

The Guardian | "Record Ocean Temperatures Put Earth in ‘Uncharted Territory’, Say Scientists"

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth