May 5, 2023

Air Date: May 5, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Oceans Hotter Than Ever

View the page for this story

The average sea surface temperature of the world’s oceans is rising as the planet warms and global temperatures recently hit all-time highs. Now the La Niña weather pattern of the last 3 years is shifting to an El Niño cycle, warming the oceans even more. Kevin Trenberth is a Distinguished Scholar at the National Center of Atmospheric Research and joins Host Bobby Bascomb to explain why the rapid warming of the oceans puts the whole Earth at risk. (10:12)

U.S. Primed for Climate Troubles

/ Aynsley O'NeillView the page for this story

Because of its unique geography, the United States is particularly vulnerable to nearly every kind of weather-related disaster: tornadoes, hurricanes, wildfires, and more. And as Associated Press science writer Seth Borenstein explains to Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill, these natural disasters are getting an unnatural boost with climate change. (09:08)

Plastic Burning Pollution Flies Under the Radar

View the page for this story

Waste incineration facilities in the US don’t have to report the dioxins and other toxic chemicals they’re emitting from burning plastic to a key database. Timothy Whitehouse is the Executive Director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility and joins Host Jenni Doering to explain the gap in publicly accessible pollution data. (10:01)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss a growing movement in U.S. cities to ban or restrict noisy and highly polluting gas-powered leaf blowers and lawnmowers. Another set of rules in California aims to reduce air pollution from diesel locomotives. And in history, whales mistaken for submarines were among the unfortunate casualties of the brief, undeclared war between Britain and Argentina over control of the Falkland Islands in 1982. (04:37)

No-Mow May

View the page for this story

Biologists are encouraging homeowners to leave their lawnmower in the garage for a month this spring to create crucial habitat for pollinators. A proponent of the "No-Mow May" movement, Biology Professor Israel Del Toro from Lawrence University joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss why we should be rethinking our lawn care habits. (07:48)

"What I Want to Believe About the Vireos"

View the page for this story

The songbirds called vireos have increased in number by more than 50 percent in recent decades, while birds overall are struggling. That was the inspiration for Poet Laureate of Mississippi Catherine Pierce’s poem, “What I Want to Believe About the Vireos.” She joins Host Jenni Doering to share and discuss. (03:43)

BirdNote®: Wetland Birds Thrive

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

While nearly a third of North American bird species are in decline, many birds that depend on wetlands are thriving. BirdNote®’s Michael Stein reports. (01:45)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230505 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Seth Borenstein, Catherine Pierce, Israel Del Toro, Kevin Trenberth, Timothy Whitehouse

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Michael Stein

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The world’s oceans are warming at an alarming rate.

TRENBERTH: 2022 was the warmest year on record for the global oceans. 2021 was the warmest year before that. Now, this is not just looking at the surface but the top 2000 meters of the ocean and so the oceans are certainly warming and that shows better than anything else actually the global warming signature.

BASCOMB: Also, due to our geography, the United States is particularly at risk of extreme weather events.

BORENSTEIN: It's almost like there's two weather patterns, one country. West is dry and getting drier and the East is wet and getting wetter. So all of those sort of combine in different ways to cause various weather extremes.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Oceans Hotter Than Ever

In the last 5 years, the global ocean surface heat content has raised by almost a full degree Fahrenheit. (Photo: Riccardo Maria Mantero, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The world’s oceans store nearly 90 percent of the excess heat produced from anthropogenic climate change and they are warming at an alarming rate. According to NOAA data the average sea surface temperature hit an all-time high last month. In just 5 years the global ocean heat content has increased by .07 degrees Fahrenheit. That may not sound like much but it’s roughly 30 to 40 zettajoules of heat, or equivalent to hundreds of millions of atomic bombs like that one that destroyed Hiroshima. And now, amid rising ocean temperatures, the Pacific Ocean is also moving away from a La Nina weather event and towards El Nino, which will cause sea surface temperatures to be warmer still. For more I’m joined now by Kevin Trenberth, a Distinguished Scholar at the National Center of Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. Welcome back to Living on Earth!

TRENBERTH: Oh, thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: So NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recently informed us that we seem to be heading out of our La Niña weather event and moving towards El Niño. What exactly does that transition likely look like? You know, what can we expect to see in the next year or so?

TRENBERTH: The last three years, we've been in this thing called the La Niña, which means it's quite cold along the Tropical Pacific from the dateline to the Americas over an extensive region. That's a region larger than the area of the United States. And so this has kept sea surface temperatures at relatively low levels. But that has changed this year. And so there is evidence that an El Niño could well be beginning and there's certainly a coastal El Niño along the coast of South America that's occurring already. And so temperatures have risen quite sharply there. And that has local effects, changing the rainfall and the weather patterns in that region and changing the fisheries. And the anticipation is at the moment that this is likely to become more widespread. So it becomes a basin wide El Niño event later this year, following an El Nño event, there's more heat that comes out of the ocean into the atmosphere. And that warms the atmosphere. And so the prospects are that certainly 2023 will be a bit warmer than it has been because of the cold sea temperatures in the tropical Pacific in the past three years. But 2024 could well break a new record and create the highest global mean surface temperature year on record. That's the expectation at the moment.

BASCOMB: And how does climate change affect what you might expect to see from a typical El Niño or La Niña pattern? You know, it's supercharged so many things in our weather, what do you expect to see in terms of how climate change will impact these weather systems?

TRENBERTH: Climate change, the increase in heating from increasing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, most of that heat ends up in the ocean. And so the oceans are expanding, the sea level is higher, the sea temperatures as a result are potentially higher, unless something like an La Niña suppresses that. And now that the La Niña is over with, all of that warmth is coming. So what we're really seeing, in some ways, is an El Niño supercharged by global warming. Now what that does in the atmosphere is it creates more evaporation into the atmosphere that warms and moistens. The atmosphere invigorates all of the storms, especially in the Pacific region, all of the typhoons and tropical cyclones and the sorts of things actually we've seen recently in California with these atmospheric rivers coming into California causing tremendous amounts of rainfall. And then the potential for flooding. And so this is one of the prospects is that we have more active weather events, but they occur in different places than they have done over the last two or three years.

BASCOMB: Scientists have also told us that they're recording an abnormal acceleration of ocean temperatures, you know, warming much more than they might expect. How does that compare to what you would normally expect in an El Niño event, you know, when the weather's shifting, and how much of that is due, you know, simply to climate change?

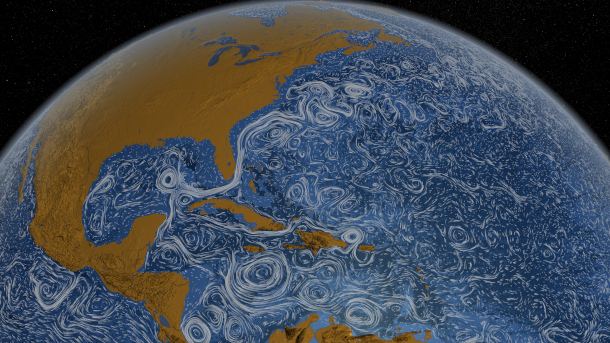

A timelapse image of ocean currents between June 2005 and December 2007 showcases the Gulf Stream in the thick line along the southeast coast of the United States. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

TRENBERTH: So we've written annual papers, my colleagues and I, over the last several years, and in January republished the assessment for 2022. And 2022, was the warmest year on record for the global oceans. 2021 was the warmest year before that. Now, this is looking at ocean heat content, it's not just looking at the surface, but the top 2000 meters of the ocean. And we have pretty good measurements of that now. And so the oceans are certainly warming. And that shows better than anything else, actually, the global warming signature. Now we've got these conditions with the change in the La Niña to El Niño and the Tropical Pacific. And so all of this is coming out now at the surface. And so the sea surface temperatures are now the highest on record. March is when the sea temperatures are normally highest. And that's because that's the equinox in the southern hemisphere, and the smaller ocean in the southern hemisphere. And so the southern hemisphere controls the overall ocean temperatures in that sense. And what we've seen just in the last month or so, is extraordinary. We've never seen sea surface temperatures this high before and certainly going in a rather different direction than all previous years. So normally, the global sea surface temperatures are beginning to cool off at this time and it hasn't happened so much this year. So this is indeed an indication that, you know, global warming is rearing its head and manifesting itself in part as this El Nino event.

BASCOMB: And what about ocean currents? You know, things like the Gulf Stream, how might those systems might be affected by increased ocean temperatures?

Even an end to human-based greenhouse gas emissions will not prevent sea level rise, as much is already “baked in”. (Photo: Geoff Whalan, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

TRENBERTH: Yeah, so that's a very good question. And it's a little hard to tell, the Gulf Stream is a part of a larger, what we refer to as Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. So it's actually goes all the way from the southern hemisphere, right up into the northern parts of the Atlantic. And it is very much affected by the amount of heat that comes into and out of the oceans. And so the prospects there are, indeed, that there can be changes in the Gulf Stream. And this has consequences for further up in the North Atlantic. In general, it's expected that the North Atlantic might not warm quite as much as some other regions, partly because of changes in the Gulf Stream, and this Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, but it still warms. And so it's a little hard to know, overall, exactly how this is gonna play out?

BASCOMB: Well, maybe this is an unanswerable question. But is there you know, a limited capacity to how much the oceans can do in terms of storing excess heat and carbon?

TRENBERTH: The oceans are quite cold at the bottom of the oceans. And there is a strong gradient in temperature called the thermocline, as we go to the top part of the ocean, so the top of the ocean is much warmer than the oceans in general. And if we put more heat in, then that increases the stratification in the ocean. And this does tend to slow down the exchanges of heat and gases, oxygen and carbon dioxide into the ocean. And so it does slow down the uptake of heat and carbon dioxide. But nonetheless, the warmer the top part of the ocean means it's more out of equilibrium with the bottom part of the ocean. And so the ocean, even if we stop global warming altogether, so called net zero, the oceans keep warming for decades and even centuries into the future. And so sea level rise goes along with that continues. So even if we begin to stop global warming, from the standpoint of the heating, the imbalance in the oceans means that they are still slowly responding. But the response does get slowed down by the fact that the ocean has become more stable. So I don't know that we've passed a particular threshold at the moment. But you know, what can indeed happen is the sort of thing we were talking about a couple of minutes ago, with a change in the track of the Gulfstream, for instance. And so big changes like that may not be easily reversible. Other changes, like melting of Greenland, if we melt Greenland, you can't put that water back in the form of a great big ice block again, readily. And so those changes are irreversible. And those are the sorts of things that mean that the future climate is simply going to be different than it has been in the past.

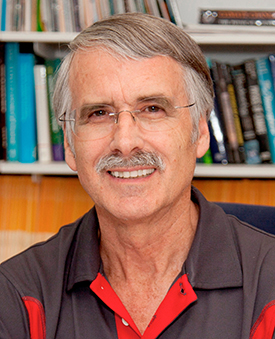

Kevin Trenberth is a distinguished senior scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research, a lead author for three IPCC assessments and a leading expert on the El Niño Southern Oscillation. (Photo: National Center for Atmospheric Research)

BASCOMB: To what degree are you hopeful or optimistic that we can get a handle on this, you know, massive problem that we've put ourselves into?

TRENBERTH: Well, I have moved to New Zealand. Maybe that's this, that's one of the factors actually, although New Zealand has got a you know, a lot of coastal problems and erosion, but is less likely to be affected by the global climate change than a number of other areas. And so the droughts and the floods in various places and the need to actually plan for those and build resilience where we can, and not enough of that is happening in the United States or in other places around the world. And so, you know, we could do a lot better.

BASCOMB: Kevin Trenberth is a distinguished scholar at the National Center of Atmospheric Research. Kevin, thank you so much for your time today.

TRENBERTH: Oh, you're most welcome.

Related links:

- CNN | "La Niña Has Ended and El Niño Will Form During Hurricane Season, Forecasters Say"

- The Guardian | "Record Ocean Temperatures Put Earth in ‘Uncharted Territory’, Say Scientists"

[MUSIC: Orchestra Baobab, “Dee Moo Woor” on Specialist In All Styles, by OrcWarhestra Baobab, Nonesuch Records, a Warner Music Group Company]

DOERING: Coming up – We’ll stay with weather and climate to take a look at how the United States is particularly vulnerable to severe weather events and the impacts of climate change. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Marian McPartland, “Yesterdays” on Timeless, by Otto Harbach-Jerome Kern, Savoy Ja]

U.S. Primed for Climate Troubles

When dry air from the Rocky Mountains combines with moist air from the Gulf of Mexico, severe weather can brew. (Photo: G. Lamar, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

As we talked about before the break, a shift towards an El Nino weather pattern and record high ocean temperatures are troubling developments for much of the world, especially the United States. Thanks to our unique geography, the US is particularly vulnerable to nearly every kind of natural disaster. We have more tornadoes each year than any other country in the world. We are also prone to hurricanes, wildfires, and blizzards. These natural disasters are getting an unnatural boost with climate change and the US can expect to be ground zero for more destruction in the coming decades. For details we called up Seth Borenstein. He’s a science writer with the climate and environment team at the Associated Press. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill.

O'NEILL: So what geographical features make the United States so uniquely susceptible to extreme weather?

BORENSTEIN: Well, you've got two oceans, the Atlantic and the Pacific. And then you have the Gulf of Mexico, which is a third coast. And then you have the Rocky Mountains right through the middle of the United States going north south. The United States is also in the mid latitudes, where you get the difference between the cold in the polar regions, and the hot in the tropics. And then you also have the Jetstream, which comes whizzing through. And it's along that Jetstream that's the instability. On one side of the Jetstream you have cold, and the other side, you have hot. I mean, you just look at the United States, it's almost like there's two weather patterns, one country. West is dry and getting drier and the East is wet and getting wetter. So all of those sort of combine in different ways to cause various weather extremes. I mean, tornadoes, hurricanes, wildfires, blizzards. You get nearly every possible one in the United States. And in many of them like tornadoes, you get it far more than anywhere else.

The US is a hotspot for tornadoes worldwide, experiencing around 1200 of these devastating storms each year. (Photo: Dough McSchooler for Associated Press)

O'NEILL: So lots of other countries will certainly have coastlines and huge mountain ranges, you know, the Himalayas or the Andes. And well, in places like Australia, they're just completely surrounded by water. So how do the weather hazards of these other countries compare to those of the United States?

BORENSTEIN: Well, Australia does have some of those issues. But if you think about it, much of these changes also brew in the center. If you have hazards in the Australian Outback, it doesn't affect many people, because there are a few people. The other thing is Australia, it's not quite in the same place where you have sort of the Jetstream plunging through. China's another good one, I kept asking when I talked to scientists in terms of comparisons. But what China has is just the one major coast, and it doesn't get the mixing or clashing of air that the US gets. I mean, it's not to say that there aren't natural hazards anywhere else. It's just we get a wide variety.

O'NEILL: Well, geography handed us a combination of dangerous ingredients. But our choices are also playing a role here. How are we exacerbating the situation?

With warming oceans hurricanes are likely to become wetter, and therefore more damaging, as the climate crisis continues. (Photo: Gerald Herbert for Associated Press)

BORENSTEIN: The key here is these are not disasters in themselves. Meteorologists and disaster experts emphasize that all these weather extremes are hazards, but they're not disasters. What makes them disasters is the human factor. If you have a tornado ripping through the Kansas wheat fields, and there's no one there and no buildings, it's not really a big deal. It's not a disaster. It is just nature. But it's when there's people and buildings in the way that it becomes a disaster. And we are putting people in places that are a little more dangerous. Think of all the construction along the US Eastern and Gulf Coast, which are hurricane prone. People build on areas where they have had total losses. And then they get hurricane insurance, federally funded usually. And then they build again in the same place. And some of the scientists said, you know, we don't do building codes as well as we should. For example, in hurricane areas, you can buy hurricane clips, which are like $20 or so, $10 to $20. These are these metal clips you put on your roof beams to help attach and keep your roof during a hurricane. And many places don't require that. It's such a cheap thing. In Tornado Alley, some places cannot build basements, but basements are crucial, or some kind of tornado shelter. A little bit under 50% of deaths they find in tornadoes, are in mobile homes or manufactured houses. If you're going to have mobile homes, maybe mobile home parks should all come with tornado shelters for people to go to. I mean, nature has dealt us a really lousy hand in terms of geography, but then we have made it so much worse.

O'NEILL: Well, the science tells us that climate change will be making storms worse, there'll be making them more common, more intense, but how exactly will they start changing in the case of something like a tornado or a hurricane?

Mobile homes do not have basements, making them more dangerous during severe weather. (Photo: Quinn Dombrowski, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BORENSTEIN: So first, tornadoes, it's more of an issue of movement. So in the Great Plains, sort of considered Tornado Alley, computer models show tornadoes decreasing in frequency there but dramatically increasing eastward like Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, Kentucky. And scientists have seen these trends starting to happen already. And eastward means more people, more poverty, more density, more trees. So you don't see the tornadoes coming. Like in Kansas or Oklahoma, you see them coming from miles away on, along the prairie. You know, if it's coming through Little Rock, there are trees in the way, you don't see a storm. And the scientists have found when there's tornado warnings, one of the first things people do is they go outside to take a look to see, ooh, is it dangerous looking. And then, and then if it looks dangerous, then they will go in the basement and take shelter. So if you can't see it because of trees and buildings, or if it's nighttime, and in the mid south, we're getting more tornadoes later at night, it's more dangerous. Then with hurricanes, most scientists are now saying more of the stronger hurricanes, and definitely wetter hurricanes. So wetter, slower, makes them more damaging. So it's not quite as easy as things being worse. It's just how they're getting worse.

O'NEILL: Sometimes it feels like those of us who live in the United States are experiencing these extreme weather events, if you'll allow me to use hyperbole, every five minutes. What kind of toll do you think that has on the American people or the American psyche?

BORENSTEIN: I think there's all sorts of possible tolls. But for a while, you say oh my god, this is happening every five minutes. And then after a while, oh, it's just another tornado killing just another 10, 15 people. There's a history in the US public of being shocked that stuff that happens, and then accepting lots of deaths as normal. School shootings. COVID. You know, it's shocking, it's shocking, and then suddenly, it's part of our daily lives. And in many ways, you know, if you think about it, weather disasters have become like that.

O'NEILL: Well, what kind of progress if any, have we made in preparing for these disasters?

Americans continue to build—and rebuild—along hurricane-prone coastlines. (Photo: Rob Olivera, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BORENSTEIN: There are still some good news. For example, lightning deaths the last few years have been at record lows. It's, you know, 10, 12 deaths a year. And in the 50s, and 40s, there were hundreds of deaths a year. And that's because of warning and education. And you know, everyone now knows if there's lightning, get off the golf course, get out of the water. One, people weren't educated in that before. And two, the warnings are so much better. So we're getting so much better about weather forecasts and warnings. The trouble is, there's a disconnect between the warnings out there and how people receive it, and what they do. And also, you know, at some point, there's only so much you can do.

DOERING: Seth Borenstein is a science writer with the Climate and Environment Team at the Associated Press. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill.

Related links:

- Associated Press | “The US Leads the World In Weather Catastrophes. Here’s Why”

- NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory | “Severe Storms 101–Tornadoes”

- The Guardian | “‘Tornado Alley’ Is Shifting Into The US East, Climate Scientists Warn”

[MUSIC: Dr. Michael White, “Give It Up (Gypsy Second Line)” on New Orleans, by Michael G. White, Putumayo World Music]

Plastic Burning Pollution Flies Under the Radar

Municipal incinerators in the US are currently exempt from regulations requiring facilities that release toxic chemicals to report those outputs to the Toxics Release Inventory. (Photo: Massachusetts Dept. of Environmental Protection, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: Just 5 percent of plastic waste is recycled in the U.S. each year. Of the other 95 percent, some winds up as pollution in the ocean, most is buried in landfills and roughly 10% is burned, generating harmful air pollutants like dioxins and ash containing heavy metals. But waste incineration facilities don’t actually have to report the toxic chemicals they’re emitting from burning plastic waste. Advocates with Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, or PEER, and Energy Justice Network are petitioning the Environmental Protection Agency to change that. Timothy Whitehouse is the executive director of PEER and he joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

WHITEHOUSE: Thank you. It's good to be here.

DOERING: So I was frankly kind of shocked, honestly, to learn that incinerators aren't actually required to report their toxic chemical emissions. Why is that?

WHITEHOUSE: That's a great question. No one's quite sure why they got exempted, probably political power. But we do know that incinerators uh release some of the most toxic pollutants known to mankind, and are often some of the most egregious polluters in the states and counties where they're located.

DOERING: So when we're talking about waste incineration, what types of waste are being incinerated?

WHITEHOUSE: So there are different kinds of incinerators. The most common that people are familiar with are municipal waste combustors or trash incinerators. So there are about 68 of these in the United States. They combust things that you throw on your garbage, it can be food waste, it can be paper, it can be couches, carpets, plastics, light bulbs, Inc. They're also hospital and medical and infectious waste incinerators. There are also sewage sludge incinerators that incinerate sewage sludge from our waste treatment plants. And there are a type of incinerators called pyrolysis. And those are incinerators that take plastics and convert them into different chemicals and gases.

DOERING: So what kinds of toxic chemicals can be released from burning those kinds of things?

WHITEHOUSE: Yes, so it's well-known that incinerators release cancer-causing chemicals. They release chemicals that induce asthma. They release chemicals that weaken our immune systems. These have been well documented by studies throughout the United States and the world. Some of the more common chemicals that people know of are lead, or mercury. There's also a toxic class of chemicals that people are becoming familiar with, called PFAS. And those are a class of chemicals that number in the 1000s and EPA requires 180 of these different PFAS to be reported as part of a toxic release inventory. There are dioxins, which are cancer-causing pollutants that are released when things are incinerated. And we know that municipal waste incinerators, the really big ones, and the bad ones, and the ones that produce the most toxic chemicals are located in low income and communities of color throughout the United States.

DOERING: So your petition to the EPA, along with the Energy Justice Network, is attempting to require these types of emissions from waste incineration to be reported to the TRI the Toxic Release Inventory. What do you hope that that would achieve?

Chemical recycling companies claim that they recycle plastic, but their process typically involves burning it, releasing toxins in the process. (Photo: Celinebj, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

WHITEHOUSE: There's a couple of things that we hope that would achieve. The basic purpose of TRI is to allow local, state, and federal governments, and emergency responders to know what chemicals are being stored and released into the water, air, and surrounding environments in their communities. And this allows the better management of these wastes. And this allows for an accurate comparison of how dangerous different facilities are, and whether greater regulations are needed of these facilities. If you don't know what these facilities are releasing, it's very hard to develop good regulations to address those releases. The bottom line is if an industry is releasing toxic materials covered by the Toxic Release Inventory, they should be required to report to the Toxic Release Inventory, no exceptions. Toxic chemicals affect the public the same way whether it's coming from an oil and gas facility, or an incinerator, or a plastics-to-energy plant. From a human health perspective, from an environmental perspective, the source of the pollution doesn't matter. So the issue should be very clear and very simple. Incinerators are a major source of toxic air pollution, but they don't need to report to the TRI.

DOERING: So Tim, I can't help but think that, you know, EPA has been around for over 50 years. And these facilities have been around for many decades as well. Have there been other attempts to you know, get these chemicals to be reported? And if so, like, why are you having to bring this action now?

WHITEHOUSE: So incinerators are required to report different releases of chemicals into various government databases, but they're not as extensive as the TRI, and they're almost inaccessible to the public. The great thing about the TRI is if you have basic computer skills, you can understand what is being released into your environment from local facilities that are required to report to the TRI. It is one of the great triumphs of EPA's transparency work. And incinerators have managed to stay out of that system. And it's very unfortunate.

DOERING: So it sounds like it's as much about public awareness as anything else here.

WHITEHOUSE: It's about public awareness. Also, the other thing I want to point out is, a lot of these incinerators produce energy. So they either produce energy in the form of electricity, or increasingly, they're creating energy in the form of creating new fuels. And so this industry is claiming it's clean and green. And it's asking for federal subsidies. And it's asking for state subsidies as a clean energy source. But at the same time, they're refusing to report their toxic release emissions to the TRI.

Exposure to air pollutants, including those from incinerators, increases the risk of diseases like cancer and asthma. (Photo: cottonbro studio, pexels, CC)

DOERING: Now it sounds like you're referring to facilities involved in so-called advanced recycling or chemical recycling of plastics when you talk about these facilities that produce fuel. Is that correct?

WHITEHOUSE: Yes, correct. That's called pyrolysis.

DOERING: Yes. So these are currently considered incineration facilities by the EPA. But I understand that the Trump administration proposed a rule that would actually deregulate these facilities by moving them out of this incineration category. And right now the Biden administration is reconsidering those rules. And they're kind of stuck in this evaluation stage. What are you hearing from within the EPA about these proposed rules?

WHITEHOUSE: So unfortunately, it appears that this EPA is considering the Trump-era proposed rules to remove these plants from section 129 of the Clean Air Act. And if they are able to remove these types of plants from the Clean Air Act, from section 129, there'll be virtually no air regulations over these types of facilities. We know that these types of facilities release some of the most toxic pollutants into the environment known to humankind. They are considering this proposal quite seriously, I believe, because there is this huge push for what's called advanced recycling, which in my mind, is locking us into a toxic carbon-based lifestyle that will wreck the climate and poison us in the wildlife around us.

DOERING: Now, from what I've been able to see this rule, it's murky, right? It's hard to see what's actually going on within EPA because they opened up a public comment period in late 2021. And, from what I've seen, they haven't released anything else publicly beyond that. But what are you hearing about where EPA might go with this at this point,

WHITEHOUSE: It's hard to know where EPA wants to go with this. But we do know from their approval of some of the chemicals that are being produced by these plants, that the direction is very troubling. For example, EPA recently approved a chemical produced from one of these plants that has a risk of one in four people being exposed to this chemical could get cancer over their lifetime. And that's an EPA assessment. That is 250,000 times greater than what EPA would normally approve. And so EPA is cutting corners to accommodate the oil and gas and chemical industry that is behind this effort. And they're doing it largely in secret. So most of the work that EPA is doing in approving these chemicals, is done behind closed doors and done under the guise of confidential business information. So we are very concerned about how EPA will approach the management and regulation of these plants that basically heat and burn plastic incinerate plastics to create new fuels.

DOERING: Tim Whitehouse is the executive director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, or PEER. Thank you so much, Tim.

WHITEHOUSE: Thank you.

DOERING: We reached out to EPA about its consideration of the Trump-era proposal to de-regulate so-called “chemical recycling” plants. A spokesperson wrote, “EPA is currently reviewing the comments and input from stakeholders on the advanced notice of proposed rulemaking.” A full statement is on the Living on Earth website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- More about PEER

- More about the Energy Justice Network

- Read the TRI data for a facility near you

- EPA Responses to Plastic Incineration Reporting Gaps

[MUSIC: Goat Rodeo, “Attaboy” on The Goat Rodeo Sessions, by Edgar Meyer/Chris Thile/Stuart Duncan, Sony Masterworks]

BASCOMB: Coming up – No mow May and the push to let lawns grow this spring to support emerging insects. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Leo Kottke, “Peg Leg” on Peculiaroso, by Leo Kottke, BMG Music]

Beyond the Headlines

Clean-air advocates claim the pollution emitted by small gasoline engines used to power lawn mowers and leaf blowers are harmful to human health and the environment. (Photo: Andres Siimon, Unsplash)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

It's time now for a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. He's our living on Earth contributor, and he joins us from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey Peter, how you doing this week?

DYKSTRA: I'm doing all right, Jenni, I hope you're doing well. And there's some good news on the horizon for any of us who like me get to listen to and inhale all of those two stroke engine, leaf blowers, lawn mowers, edgers, all the lawn equipment that's in use by commercial firms and homeowners that are both a climate change threat and a threat if they're used without protection to the lungs and ears of hundreds of 1000s of people. But there are several jurisdictions that have now stepped forward or are stepping forward to begin to ban or restrict these noisy polluting unhealthful machines.

DOERING: Wow, that's probably good for our health and our sanity. So what are the places banning these things Peter?

DYKSTRA: Places like Washington DC have had an outright ban to $500 fine for using any of these gasoline engines. California has restrictions rolling in in the next few years. Burlington, Vermont, Vancouver, British Columbia, Denver and other cities and jurisdictions are coming to realize that the cost of a well manicured lawn shouldn't be potential pollution, lung disease, asthma, and all of the things that gasoline engines from lawn equipment can bring.

DOERING: And by the way, elsewhere in the broadcast, we've got a segment about no mo may if you want to skip the mowing entirely.

DYKSTRA: No mo may and then there are other things like zero scaping the practice of landscaping without ornamental grass and using as little water as possible.

DOERING: All great ideas. What else do you have for us this Peter?

DYKSTRA: California develop emissions rules for locomotives. There's diesel locomotives that are particularly intensively used in California. Ports, like Long Beach that receive container ships from Asia and really all over the world to bring goods to America that are then loaded onto either trains powered by diesel locomotives, or trucks powered by diesel engines. It's not only a climate issue and a public health issue. But it's considered to be an environmental justice issue, since places like Long Beach tend to have poor and minority neighborhoods backed up to big cargo ports and terminals.

California approved a rule that will ban diesel locomotive engines more than 23 years old by 2030 and increase the use of zero-emissions technology to transport freight from ports and throughout railyards. (Photo: Ankush Minda, Unsplash)

DOERING: So it's good news for those communities. But what is the industry saying Peter?

DYKSTRA: The industry is not too happy. They've seen this coming for a while. They are of course, slow to respond. But electric vehicles have pretty much arrived. Electric trains have been around for a long time. It's a little bit more complicated to get freight trains operating on electricity, but it's something that can be done. And increasingly we're learning that for health and climate reasons it eventually has to be done.

DOERING: Wonderful. So from looking ahead to the future, let's look back into the past now, Peter, what do you got for us?

DYKSTRA: On May 12 1982, something really strange happened. According to crew diaries from the Royal British navy, who in 1982 was at war with Argentina for control of the Falkland Islands, the HMS brilliant British navy ship torpedoed at least two Southern Right whales, thinking they were Argentine, mini subs, there's a helicopter that may have killed a third whale. We don't know about others. But it was a really bizarre and unfortunate case of Southern Right whales becoming casualties of war.

Crew diaries revealed that on May 12, 1982, the British Navy torpedoed endangered Southern right whales, after mistaking them for enemy submarines. (Photo: Olga Ernst, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DOERING: I imagine it must have been pretty gruesome for these crews to discover that they had not in fact targeted a submarine but a majestic whale.

DYKSTRA: Gruesome enough that it wasn't talked about for many years. Until these crew diaries were revealed. Southern Right Whales are considered to be a separate species from Northern right whales. The southern whales are still endangered, but not nearly as gravely threatened as the northern right whales.

DOERING: Well, thank you so much. Peter, Peter Dykstra is a weekly living on Earth contributor, and we'll talk to you again next week.

DYKSTRA: All right Jenni, thanks a lot. We'll talk to you soon.

DOERING: And there's more on the stories on the living on Earth website. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- USA Today | “Gas Leaf Blowers and Lawn Mowers Are Shockingly Bad for the Planet. Bans Are Beginning to Spread.”

- AP News | “California Passes 1st-In-Nation Emission Rules For Trains”

- The Times UK | “Royal Navy Ship Torpedoed Whales in Falklands”

[MUSIC: Luizinho Vieira & Brazil Exess, “Papai Oxala” on Musica Negra In the Americas, by Luizinho Vieira, Network Records]

No-Mow May

Leaders in the “No-Mow May” movement stress that there is a key window of time–anywhere from February to May depending on an area’s climate–when vital food sources for pollinators should be allowed to flourish. (Photo: Ivan Radic, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Spring is in full swing across the North and some may feel the urge to get out the lawn mower and tidy up but there is a growing push towards letting our lawns grow for the month of May. The No Mow May movement aims to give insects just emerging from hibernation access to critical sources of food like dandelions and violets before we mow them down with the grass. Insect populations, including many critical bee and other pollinator species, are in dramatic decline, threatening food webs in nature and food security for humans. But communities that let the grass grow this month have seen a tremendous increase in pollinators, a 5-fold increase in pollinator abundance and a threefold increase in the diversity of insects. Israel Del Toro is a biology professor at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin, one of the communities that has embraced No Mow May.

DEL TORO: The idea is pretty simple. May is actually a really important time for our pollinators that are just coming out of hibernation. So many of the species of bees that we have in the US are solitary bees that over-winter underground. And so the idea behind No-Mow May is to basically let our lawns grow out and provide some early season flowers for our pollinators that are coming out of hibernation to feed on.

BASCOMB: Well, this time of year in my own yard, I'm seeing dandelions and some violets coming out. But what kind of flowers are we talking about here? I'm sure of course, it's gonna to vary across the country, but generally, what are you seeing?

DEL TORO: Yeah, things that we would normally consider weedy species are actually really important food sources for our pollinators. So things like what you just mentioned: dandelions, clovers, violets, all of those are resources, whether native or not, that our native bees are actually depending on. Now, don't get me wrong, I'm all about removing invasives and reducing invasive species as well. But we also want to make sure that we strike a balance in working with the biodiversity in our backyards.

BASCOMB: Well, tell me more about the insects and pollinators specifically that we're talking about here.

There are about four to five thousand species of native bees in the United States alone, and many of them rely on naturally growing vegetation in urban spaces. (Photo: Allison Richards, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DEL TORO: Yep, so pollinator diversity is actually really huge. If we look at the entire US as a whole, we're looking at about four to five thousand different species of native bees. Most of them are solitary bees, and actually very few are colonial like honey bees, or semi-colonial like bumblebees. The rest of them tend to be solitary. They nest underground, they nest in decaying wood. Some of them lie in their burrows with leaves, those are your leaf cutter bees, or others will dig out little burrows inside of walls. And those might be your mason bees. And so we have quite a big diversity of bees. Here in Wisconsin, we have about 500 different species of bees that are native to Wisconsin. And amongst that biodiversity, we also have rare and endangered species. So a good example of that is the rusty patched bumblebee. The rusty patched bumblebee is federally listed as it's a critically endangered species due primarily to habitat loss. But one of the cool things that we're seeing is that these urban habitats that we're generating as a result of No-Mow May, can actually result in bringing back some of those populations into urban spaces.

BASCOMB: So even somebody that maybe doesn't care so much about bees or insects, but might like to hang that bird feeder outside their window and see birds, maybe they should think about taking up this No-Mow May. I mean, insects are so foundational to many species that we care about.

DEL TORO: Absolutely. So with insects being at the base of many of these food webs, birds and other small mammals rely on them as a part of their diet. So by increasing the abundance of insects in general, we can really start to help the broader ecosystem as well. One of the other cool things that we see as part of No-Mow May, so let's say animals and insects and birds aren't your thing, but maybe plants are your thing. No-Mow May also gives an opportunity for rare and endangered species of plants to pop up, things that might not normally show up.

BASCOMB: Wow, that's really interesting. So it sounds like May specifically is a really critical window for a lot of things.

DEL TORO: Yep, May is when nature is waking up from winter, right? Now depending on where you are in the US, No-Mow May may might not be the right time for you to not mow your lawn. It might be No-Mow April if you're further south, or No-Mow March, just depending on where you are, and wherever the seasonality is appropriate.

Bees are not the only species that can benefit from No-Mow May. A variety of rarer plants and insects are also free to thrive when our lawns are not as manicured. (Photo: Yamanaka Tamaki, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, how big is the potential impact of yards, for pollinators and for wildlife in general? I mean, we grow a lot of grass in this country.

DEL TORO: That's right. So grass is probably our predominantly most homogeneous crop that we grow as a country and we manage it so heavily, right, we put all of these chemicals, fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, and to have that greenest lawn. And maybe this is an opportunity for us to rethink some of those habits and educate ourselves on what the best practices are, and maybe reducing our fertilizer use or reducing harmful chemicals that are known carcinogens. For example, glyphosate and neonicotinoids are really bad for our pollinator populations. But they're also really bad for us humans. The European Union, for example, has declared glyphosates as known carcinogens, and we still keep putting them on our lawns, and often overusing these chemicals. So this is an opportunity for us to think about what's good for the environment, but also what's good for our own health and our practices on how we manage our little bits of plots of land.

BASCOMB: So we've been talking about holding back on mowing our lawns. What about cleaning up, you know, last year's leaves or pulling out those dead flower stalks? I understand a lot of insects make their winter homes in places like that.

DEL TORO: Absolutely. So No-Mow May isn't just an opportunity to be lazy. In fact, I encourage you to do the opposite. I encourage you to spend that time that you would normally spend mowing, educating yourself about other things that you can be doing for our pollinators throughout the summer and into the fall. And as you mentioned, going into the fall is a really important time where we can help create habitat, nesting habitat for these solitary bees. We like the idea of "leaving the leaves." The other great thing about leaving the leaves is that it becomes great compost for your yard and for your lawn in the next year. So not only are you protecting your pollinators, but you're fertilizing your landscape as well along the way

BASCOMB: Well, Israel, I have to tell you that this has become a bit of an issue in my own house here. My husband mows the lawn. And he's already talking about how long the grass is getting, I kind of think he's worried that the neighbors are gonna judge us for not keeping our yard neat enough. How do you respond to someone with those kinds of concerns?

While many may view plants like dandelions as a nuisance, they are actually important to a wide variety of pollinators. (Photo: Yoshiyuki IMAI, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DEL TORO: Yeah, so the big thing is open communication and talking to your neighbors about what you're doing and why you're doing it. So if you decide to grow out your lawn for the month of May, the first thing we ask you to do is check with your local municipality to make sure that you're not violating some city ordinance. However, if your town is participating, or you are within your city ordinances, then you know, by all means, just talk to your neighbors. Let them know that yeah, my lawn’s gonna be a little shaggy this month. But that's okay. This is why I'm doing it. And I promise, come June, I'm gonna mow that thing. And we're all gonna be looking top shape. And you know, one of the things that we do is we provide signage for our communities to let people know that our wild looking lawns actually is a sense of organized chaos, that there is method to our madness, right, that we're not just being lazy gardeners, we're actually thinking about providing homes for our pollinators.

BASCOMB: So No-Mow May isn't a slippery slope to bedlam, then. It’s gonna be okay.

DEL TORO: No, I think No-Mow May is more of a slippery slope into learning about your biodiversity and educating yourself and your family, about the little things that crawl outside our house that are really important for our ecosystem.

BASCOMB: Israel Del Toro is a biology professor at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin.

Related links:

- Xerces Society | “No-Mow May Sign Download”

- Pollinator Friendly Alliance | “What is a pollinator lawn?”

[MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “Long Boats’ on Mississippi, by Eric Tingstad, Cheshire Records]

"What I Want to Believe About the Vireos"

A vireo perches atop a twig. (Photo: yuki_alm_misa, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Letting your lawn go a little wild this May can help emerging insects and a cascade of other animals that eat insects including may bird species. And that’s crucial right now as North American birds have declined roughly 30 percent since 1970, mostly due to habitat loss, invasive species and predation from cats. But some birds seem to be doing just fine despite these challenges. Vireos grew by more than 50 percent since 1970. These songbirds are a rare example of a species that’s prospering amid the ecological crisis we’re causing, inspiring this imaginative poem from the poet Laureate of Mississippi.

PIERCE: I’m Catherine Pierce, and this is my poem, What I Want To Believe About The Vireos.

The vireos are plotting.

They are everywhere and various

and all with names

like Shakespearean villains

disguised as Shakespearean clowns.

Black-whiskered.

Plumbeous. Slaty-capped

shrike. Their songs drop

from the canopy like candied

needles, and everyone smiles. Sweet

birds. They’ve been above us

for centuries, watching. See

their eyes: small bright

pebbles that betray

nothing. They know

patience. See them tableau’d

on the oak branch

for minutes before diving

for the fat black beetle.

They know how green works,

how it muscles back, always,

once the pillars and poisons

are gone. They’re playing

the long game. Weary,

weary, weary, trills the scrub

greenlet. It’ll all be theirs

again—rain forests, mangroves,

the great deciduous rustle.

The breeze and moss.

The loam and sunrise.

The vireos will be here

at the end and at the next

beginning. The red-eyed

vireo’s call will sound then

like it does now, like

it’s constantly asking

and answering

its own questions.

What did they do?

They did.

What did they know?

They knew.

Catherine Pierce is the author of four books of poems including Danger Days and The Tornado Is the World and is professor of English and co-director of the creative writing program at Mississippi State University. (Photo: Megan Bean / Mississippi State University)

DOERING: They seem to have such agency in this poem, as you imagine it.

PIERCE: Yeah, I wanted to sort of give the birds credit. I was imagining this as they're playing the long game, as it says in the poem. They see the destruction that's being kind of brought to their habitats. And they're, they're playing the long game, they're going to wait it out, they're going to stick around. They imagine that eventually humans will kind of... they'll kind of eradicate themselves, and then all the green will come back and all the birds will come back. And so it's, it's a bleak fable, but it's only bleak for the humans. I think it's really good for the birds.

DOERING: And what about us? Are we playing the long game? Do you think? I don't get that sense from your poem.

PIERCE: You know, I mean, I think that this poem is, you know, and I wrote this several years ago, and things seemed maybe even bleaker than they do now. So I think it's good that I don't know that I would have necessarily written this poem in the same way, if I wrote it now. I do have a little bit more hope now that some things are changing, that some policies are getting better. I think some people are playing the long game. I don't yet think enough of us are playing the long game for thinking about sort of, you know, sustaining this planet, the only planet that we have. But I think that more and more people are beginning to think that way. And I think that more policies are beginning to change. And so I'm hopeful, I'm cautiously hopeful that maybe we'll be moving more toward that as time goes on.

DOERING: That’s Catherine Pierce, poet Laureate of Mississippi. Her latest book is called Danger Days.

Related links:

- Catherine Pierce’s website

- Find Catherine Pierce’s book of poetry, “Danger Days”, here (Affiliate link supports LOE & indie bookstores)

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Wetland Birds Thrive

A painting of two ducks from South Dakotan artist Adam Grimm. (Photo: Adam Grimm, USFWS)

BASCOMB: Well, the vireos that Catherine Pierce writes about aren’t the only birds that are thriving. BirdNote’s Michael Stein has more.

BirdNote®

Wetland Birds Thrive

[Dawn song of birds in a freshwater marsh]

While nearly a third of North American bird species are in decline, many birds that depend on wetlands are thriving. [Call of Redheads]

The main determinant of duck breeding success is the condition of wetlands and upland habitat on the prairies and in the boreal forest. After the extended droughts of the 1980s, conditions on the breeding grounds improved when the rains returned. And, waterfowl hunters, through organizations like Ducks Unlimited, have provided hundreds of millions of dollars to conserve and restore wetlands.

It’s not just ducks that benefit. Nearly one quarter of US birds, such as this Virginia Rail, rely on freshwater wetlands. [Calls of Virginia Rail]

Yes, challenges remain. Breeding habitat in the prairie pothole region is under increasing pressure for conversion to agriculture. But wetland birds respond to our efforts. For example, in spring, in wetland-rich areas protected by conservation programs in the Dakotas, you can find more than 100 breeding pairs of ducks on a single square mile of prairie. [Quacking of hen Mallard]

A Virginia Rail in the waters of Montlake Fill. (Photo: Gregg Thompson)

###

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Dawn chorus at Malheur National Wildlife Refuge [uned] recorded by G.F. Budney; quacking of hen Mallard [3420] by A.A. Allen; calls of Redheads [59598] by W.W.H. Gunn; call of Virginia Rail [107435] by W.L. Hershberger.

BirdNote's theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Written by Todd Peterson

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2016 Tune In to Nature.org March 2014/2016/2020 Narrator: Michael Stein

ID# SotB-wetlands-01-2010-03-21 SotB-wetlands-01b

http://www.ducks.org/conservation/waterfowl-surveys/2013-duck-numbers

http://www.ducks.org/conservation/waterfowl-surveys/2013-duck-numbers

Young, Matt. “Rescuing the Duck Factory”, Ducks Unlimited magazine. November/December 2008. P.71

http://www.ducks.org/news/1305/Ducknumbersupslightl.html

https://www.birdnote.org/show/wetland-birds-thrive

BASCOMB: For photos flock on over to the Living on Earth website, LOE.org.

Related link:

Listen on the BirdNote® Website

[MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “Tennessee Rain” on Mississippi, by Eric Tingstad, Cheshire Records]

DOERING: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Fern Alling, Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Jusneel Mahal, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth