Finding the Mother Tree

Air Date: Week of May 12, 2023

“Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest” takes readers into the field with Suzanne Simard as she describes her forest experiments and shares how her findings helped her through the challenges of motherhood and a cancer diagnosis. (Photo: courtesy of Knopf)

An intricate web of roots and fungi connects life in an old growth forest, allowing ancient “Mother trees” to nourish and protect their kin. Forest ecologist Suzanne Simard studies these connections at the University of British Columbia and takes readers into the field with her in her book, Finding the Mother Tree. She joins Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to share her research findings and reflects on how these trees helped her through the challenges of motherhood and a cancer diagnosis.

Transcript

CURWOOD: At the top of the show we talked about mammal mothers.

Now we consider the mothers known as mother trees. Ancient trees are crucial to the health of a forest. And they can communicate through networks of soil fungi called mycorrhiza. Ecologist Suzanne Simard found that trees can send warning signals and additional nutrients to their own offspring in greater amounts than to unrelated trees. Suzanne wrote a book about her ecological discoveries that is also a memoir about her own experience of motherhood as well. It’s called “Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest.” She teaches forest ecology at the University of British Columbia and spoke with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

DOERING: So, you just really have this way of looking at a forest and seeing so much more than I think most of us ever do. Where do you trace your connection with the forest back to?

SIMARD: Well, I grew up in forests. So you know, I live in a province of forests in British Columbia, and there's so many different kinds, but I grew up in what are called the inland rain forests, beautiful, huge trees, cedars, and hemlocks, Bruce's larches. birches, it's very, very species diverse forest for the Pacific Northwest. And so I grew up there, my great grandfather, my grandfather, my dad and uncles were all horse loggers, and seeing how, you know, how to live in forests and make a living out of it without actually destroying the forest.

DOERING: It sounds like understanding the forest being in the forest is in your blood.

SIMARD: Yeah, well, it is. It's also in my DNA, because it was like multiple generations of families doing this, our family doing this. So yeah, I kind of grew up with it in my background, and my blood, my bones, my DNA.

DOERING: Well, what got you curious, in a scientific way about the connections between trees and the rest of the forest?

Simard grew up in the forests of British Columbia and often camped with her family. Left to right: her brother Kelly, three; sister Robyn, seven; mother Ellen June; and five-year-old Suzanne. (Photo: courtesy of Suzanne Simard)

SIMARD: Yeah, so after I grew up, I became a forester, myself. And when I entered into the forestry profession, at the age of 22, I started to learn that, you know, when I grew up with my grandfather, horse logging wasn't at all what the forest industry had become. It had become, you know, this clear cutting machine that wouldn't just take out the odd tree here, and there wasn't selective logging, it was clear cut logging. And that means, you know, taking every tree out, and my job at the time was to replant these forests, with trees, seedlings and try to help them recover. But what I found was that, you know, when you don't have you know, surrounding trees, and good soil, that it's harder to get trees growing. And so I saw this and the practices that were getting hold like herbiciding the native plants to get rid of them to make way for these trees that we were planting to give them a better shot at sun and light, and water, actually was having, you know, a detrimental effect on the trees. So the trees actually seem to need these native plants around them as part of their successional process of, you know, healing the land. And that was that what I was seeing that started to get me to look below ground at what we might be doing wrong.

DOERING: So you noticed as a forester, when you were trying to help these plantations succeed, you noticed that they just weren't regenerating very well. They weren't healthy. They didn't seem like they were going to survive. How did you then go about trying to figure out what could help them survive?

SIMARD: Yeah, so one of the things I noticed, you know, some trees would do really well, but others would suffer from pathogens and insect infestations, and especially a root pathogen was infecting a lot of the Douglas firs and it would spread from fir to fir to fir and affect the whole plantation. And so I thought, well, if it's a root pathogen, I need to look below ground at what's going on here. And these root pathogens, these fungal pathogens, really were attacking the big roots of the trees and then girdling them in other words, infecting the base of the tree, and then they would just die within a year or two. And so I thought, well, we're disrupting the soil balance. So I started looking at the fungal communities below ground, there's thousands of species of fungi, you know, there's kind of three or four main groups: there's pathogens, like I mentioned, that kill trees, there's saprotrophs, which decay stuff, and there's mycorrhizal fungi, which are helper fungi. Which by the way, mycorrhiza literally means fungus root. It's a relationship, a symbiotic mutualistic relationship between trees and fungi, where the tree provides photosynthate or carbon energy to the fungus. The fungus then uses that energy to grow mycelium through the soil. And as it does that, it kind of coats all the particles and soil pores and draws out the nutrients and delivers it back to the plant or the tree in exchange for this photosynthate. So they both are benefiting from this. And I learned in my research that these fungi can actually connect trees together, they can connect trees of the same species, they can even connect trees of different species. And I found out that in my research that paper birch, which was a target of these herbicide treatments, because it's shading the fir.

A clearcut in British Columbia. (Photo: meaduva, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

DOERING: It's a competitor.

SIMARD: Yeah, as a competitor, that it actually was connected to Douglas fir, and delivering carbon to Douglas fir, which, you know, we hadn't thought of that before. And that kind of changed the equation then like it's not just a competitor. It's actually also a collaborator at the same time.

DOERING: What could your discovery of how carbon moves between trees with the help of fungi mean for our climate change efforts?

SIMARD: Lots and lots. So for one forest cover a third of our terrestrial land base, they contain about 80% of our terrestrial carbon. And so they're hugely important in the carbon budget. And of course, we know carbon is sort of, you know, a key indicator of climate change. And so forests are important in this, anything that happens to forests affects the global carbon budget. And we are affecting our forests every single day. What my research shows is that keeping these old forests, these old trees, the mother trees, which are sort of the linchpins, or the nucleus of the recovery of forests from any kind of disturbance, whether it's fire or logging or insect infestations, these old trees are essential in the recovery of the forests in the regeneration of the forest. But they're also really important because these old forests, especially old growth forests, which are you know, basically the most ancient forests, they store so much carbon in the soil in their trunks. And they're also rich in biodiversity, the fungi in the soil, they support the lichens in their crowns, the birds that use them and the animals, so on these old forests are hubs of biodiversity. But we're logging them at this incredible rate right now. In where I live in British Columbia, we really only have 3% of our valley bottom, huge old growth forests left. And this isn't just happening in British Columbia, it's happening around the world. The other thing that my research shows is if we're going to log, which we're going to continue to do, but we can focus our logging in areas where it's not so impactful on biodiversity and carbon budgets. But where we do it, to leave the old trees behind, you know, don't just take them because that is, you know, historically, that's what we've done. We, we high grade the biggest trees, but it turns out, they're the most important trees in the recovery of the ecosystem. So the harvesting shouldn't be clear cut harvesting, like we're practicing worldwide now, it should be selective harvesting. It should be leaving these old trees behind to facilitate the recovery of the forest.

As a young forester, Simard noticed that the seedlings planted after a clearcut were often sickly, and her observations prompted a whole career of research on mother trees. (Photo: © Bill Heath)

DOERING: So you write, that these fungi that connect trees in a forest might be able to evolve and adapt much faster to a changing climate and help the trees adapt too. So how could that work?

SIMARD: Yeah, that's a great question. Um, so you know, trees, of course, they're the foundation of the forest. They're photosynthetic. They're what links carbon in the sky to carbon in the soil, they convert light energy to chemical energy and drive all of our cycles. So whatever happens to trees, happens to all of us. And so really, to keep the biosphere in balance, we need to maintain forest cover across the globe. And we're losing it really quickly, you know, not just because of logging, but wildfire and insect infestations that are driven by climate change. And so trees are not going to be able to migrate or adapt as quickly as they need to, to keep up with the velocity at which climate is changing. So what is their other choice? Well, a lot of them are going to die. And we're seeing that. And yet, you know, because you know, evolution and trees take so long but evolution and fungi doesn't take as long fungi have a shorter lifespan, right, they reproduce within a year, they can mutate and be different from one year to the next. And so they can actually serve as an interface between the rapidly changing climate and the more slowly changing trees. And so the one way that we can sort of capture that adaptation or adaptability of the fungi is to make sure that trees have their appropriate microbiome, which is the fungi, the bacteria that have short lifespans, short life cycles are healthy in the soil. And that can help the trees survive, and possibly migrate a little bit further. The other thing that we need to do though, is we need to assist the migration of trees and the fungi, to keep up with the velocity of climate change to make sure that in the new environments that they're in, that they're able to cope as best as they possibly can.

DOERING: Your book, "Finding the Mother Tree" is also a memoir. How does your quest to understand mother trees resonate with your own experience of motherhood?

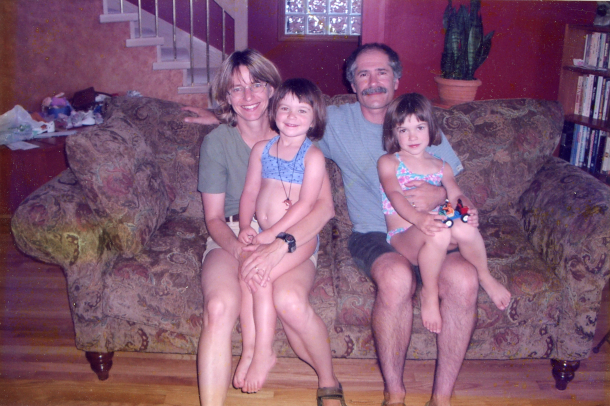

Simard and her family in 2005. (Photo: courtesy of Suzanne Simard)

SIMARD: That's a great question. So I wrote the book because I wanted the science to get out. But I also wanted to show that science is such a personal journey, right? It's not something to be distrusted. It comes from us. It comes from our hearts, it comes from our curiosity, to make sense of our world. And, you know, the work that I did was a reflection of my life. And so I started, the questions that I asked came from my experiences in the forest, but also as a mother, myself, and I found that the trees told me about motherhood. And I informed my research about looking at motherhood in forests, or the role of nurturing and forests, because I was going through that myself. And the role of, for example, sickness as well, I had breast cancer and I wanted to understand what if an old tree is sick and dying? What happens? Is there a connection with their kin, their children? And can that inform how I'm going to respond to this? And so, actually, when I got breast cancer, I set up a series of experiments with my graduate students saying, What if a mother tree is sick? What if she's injured? What if a mother tree is dying? And we found that these dying mother trees would actually send warning signals to her own kin more so than strangers, as well as provide more carbon energy to those kin seedlings so that they could grow bigger networks and grow healthier and stronger. And that sort of was a way of those trees of passing on their life energy into the next generations. It's a very Darwinian, in a way, it's survival of the fittest. Honestly, I don't think I would have asked those questions if I hadn't gone through this experience myself. The trees have taught me so much. And of course, when I learned this, I was already, you know, passing things on to my kids in case I didn't make it. And then I did make it, but I learned a lot about, about the importance of, of where to put your energy when the stakes are really high.

Suzanne Simard has published over 200 peer-reviewed articles and her work has influenced filmmakers (the Tree of Souls in James Cameron’s Avatar). Her TED talks have been viewed by more than 10 million people worldwide. ( (Photo: © Diana Markosian)

DOERING: Before you go, Suzanne, what you've been able to uncover in the forest is really profound, these deep connections between all the species in the forest. You say that we don't have to be a forestry scientist to deepen our own connections with the natural world. So how can we try this at home?

SIMARD: Yeah, I mean, there's so many things you can do. So I mean, the first thing is just being reconnected with your trees, your plants, what you have around you, most of us have access to some kind of natural plant community, and just being with them helps you to reconnect. And when you get that connection back, then you'll fight for the forest. So that is the absolutely the first step. You know, it's like falling in love. You know, once you fall in love, you care for that person and you keep, you know, you nurture that relationship. It's the same thing with your connection with forests. And then from there, the actions you can take, of course, you know, you can make choices like don't buy, you know, furniture that's from a tropical tree that's endangered, try to reduce your consumption of cardboard and toilet paper and paper products, making choices as a consumer. And that sends a strong message to the companies that are logging forests, you know, making sure that they're sustainable practices. And you can do that by looking at you know, certification, which has its own flaws, but in a sense, you have a lot of power as a consumer to boycott those companies that are basically mining forests. And then of course, the next step is to become beyond that is to become active in the change itself, the change makers, the ones that are on the lines, maybe a protester, or maybe a writer, or you know, doing interviews like this, those are all important steps as well. Getting the word out educating, getting people aligned so that we all care and fight for our planet because we need it to survive.

CURWOOD: Suzanne Simard is a professor of forest ecology at the University of British Columbia and the author of "Finding the Mother Tree." She spoke with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Links

Author Suzanne Simard’s website

Learn how to get involved with the Mother Tree Project

Watch Suzanne’s popular TED talk, “How Trees Talk to Each Other”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth