May 12, 2023

Air Date: May 12, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Amazing Animal Mothers

View the page for this story

This Mother’s Day we’re celebrating the tenacity and tenderness of animal mothers, from crocodiles to leopards to whales. Aletris Neils is the executive director of Conservation CATalyst and joined Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb to share why observing mother orangutans inspired her own journey to becoming a mother. (09:09)

Bringing a Plastic Giant to Justice

View the page for this story

The 2023 Goldman Environmental Prize winner from North America went toe-to-toe with one of the largest petrochemical companies in the world, Formosa Plastics, and won a $50 million settlement over its illegal dumping of toxic plastic waste. Diane Wilson joins Host Steve Curwood to share her story of dogged truth-seeking and holding a major polluter accountable for spoiling the biodiverse landscape of the Texas Gulf Coast. (19:18)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss new Indigenous reserves in the Brazilian Amazon totaling a million and a half acres. They also unpack how in the U.S., Indigenous care for the forest, including traditional burning, has been disregarded and contributed to massive wildfires in California. In history they look back to the man who gave Cape Cod its name. (04:59)

Finding the Mother Tree

View the page for this story

An intricate web of roots and fungi connects life in an old growth forest, allowing ancient “Mother trees” to nourish and protect their kin. Forest ecologist Suzanne Simard studies these connections at the University of British Columbia and takes readers into the field with her in her book, Finding the Mother Tree. She joins Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to share her research findings and reflects on how these trees helped her through the challenges of motherhood and a cancer diagnosis. (13:24)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230512 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Alertis Neils, Suzanne Simard, Diane Wilson

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

A Texas woman brought a giant plastics company to justice with the help of whistleblowers.

WILSON: If there has been a spill, you don't hear it from industry - you hear it from the workers. And I would get calls at midnight, I would get calls wanting to meet in parking lots, wanting to meet in alleys. I've become quite good at being a private detective, actually!

CURWOOD: Also, in honor of Mother’s Day, we take a look at animal mothers.

NEILS: When you see a bear and these moms playing with their cubs and these cubs look like they can be quite annoying. They're winning at the mom and she's trying to nap. The amount and tolerance and love that exist for their babies is something that I think all mothers can relate to.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Amazing Animal Mothers

During the first two years of life, baby orangutans rely on their mothers for food, transportation, and protection. (Photo: Ucumari Photography, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Mother’s Day is upon us and so I’d like to wish a happy Mother’s Day to all including Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb, the mother of two growing girls. Happy Mother’s Day, Bobby!

BASCOMB: Thanks, Steve. Of course, you must also remember the mothers living in your personal life, your wife and daughter.

CURWOOD: Oh yes, Sunday brunch is a tradition in our family.

BASCOMB: Sure, that’s the classic, of course you can’t go wrong with flowers as well.

CURWOOD: Sure, and I can even pick em now

BASCOMB: Oh I love that. But you know I’ve been thinking a bit about animal mothers and strategies they’ve evolved for dealing with the challenges of motherhood without the benefit of medicine and schools, things human mothers rely on. So, I called up Aletris Neils, she’s the executive director of conservation catalyst and author of an upcoming book devoted to mammal mothers. Welcome to Living On Earth.

NEILS: Thank you so much for having me.

BASCOMB: Well, what is it about animal mothers that drives them to protect their children so fiercely. I mean, the classic thing you know, probably everyone has heard of is that you don't want to mess with a mama bear, for instance.

NEILS: So typically animals that have really long gestation, longer periods of maternal care, those are the animals that are the fiercest mothers. So they will do kind of everything in their power, including put their own lives at risk to protect their young animals, like bears that you might invest years in their cubs are an excellent example of that. Even animals that we don't think of as being very maternal animals, like crocodiles are actually fantastic mothers. And so when I worked on crocodiles these moms would ferociously guard their nest, ferociously. You don't want to mess with a mama crocodile.

BASCOMB: [LAUGH]

NEILS: Like, you know, most crocodiles when they see people will just absolutely go the other direction. A mother crocodile is the exception, like she will charge you, she will come right after you, particularly if you're near her nest and so she'll defend that nest. And then when those babies start hatching, they start making these really sweet little chirping noise. And she'll go and actually help undig the nest and very, very gently open those eggs sometimes if the baby's stuck, and then put them in her mouth and carry them down to the water, because that's a period where there's a lot of potential predation, you know, where those babies are very vulnerable. And she'll stay and guard those babies. And in cases now, it's been documented where she'll actually make kills, and hold the meat in her mouth and let the babies feed off of it. So I think the more we learn, the more we start to understand that so many animals are just incredible mothers.

A mother jaguar must teach their offspring skills such as hunting, stashing food, swimming, and fighting off predators. It’s a demanding process, so a mother jaguar mates every 2 years to give her the energy to raise and teach her cubs. (Photo:Tambako the Jaguar, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Now, you've spent a lot of your career studying big cats largely in Namibia, what have you observed between mothers and their cubs there?

NEILS: Yeah, so big cats are just such spectacular moms, not only because I mean, their lives are just so difficult. I mean, if you imagine, you know, big cat is really always operating on the margins. And so there are, you know, no grocery stores and there are no food reserves, if a cat doesn't make a kill, it doesn't eat, and if it doesn't eat doesn't live. And so you can just imagine these big cats that are out on this landscape, and they're pregnant and very pregnant but still, at the same time, they have to, with this giant, cumbersome, engorged uterus, still go out there and take down, you know, an impala or any of these animals that are quite formidable and really difficult. And if they don't do that, they don't survive. And then immediately after she gives birth, she has to feed those young and that's very energetically expensive. And so then it's same time right after she's gone through and given birth, and she has to go back out and make a kill again and continue doing that, if she's going to successfully raise those cubs. And something that I find so fascinating, you know, when mammal instincts or an animal instincts conflict with one another and so, in some cases, that motherhood instinct, just so completely overrides the survival instinct, or that motherhood instinct is so strong that animals will actually adopt other species. And so there's these, you know, rare examples of a leopard mother that will adopt a baby baboon, and so it's picking up on those, probably the cues of this baby crying, and any mother can relate to this, when you hear a baby crying anywhere, you're just hardwired to respond to that, possibly pheromones that that baby has as well. And you know this mother leopard, I mean leopards eat baboons, you know, they're considered to be enemies in a lot of situations, but yet we'll carry around and care for a baby baboon. And you know, in cases of lions, doing the same thing with antelope, where, you know, they will find baby antelope and instead of eating them will take care of them and actually protect them from other lions. And so, you know, I think that motherhood instinct that motherhood drive is so strong, that it can absolutely override everything else. It's just really amazing.

Mother bears are considered one of the most protective mammals when it comes to the safety of her cubs. (Photo: Arend, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: I mean, that is amazing. You think of a young antelope is easy pickings for a lion. That's, you know, the first thing that would go for the young, the old, the infirmed. It's amazing to think that the drive to motherhood can override you know, the instinct to hunt and to feed yourself.

NEILS: Yeah, precisely. And one of these examples it was a mother lion who lost her cubs and you know, was probably mourning for those cubs and then picks up the pheromones from this, you know, baby willdebeest, and then that just overrides everything. And she just protects this wildebeest, even from, from other lions that want to eat it. And, you know, we think about these gray whales, I mean, these are mothers that their food is up in the Arctic, it's up in Alaska, yet they need a safe warm place to have their babies to have those calves. And so they migrate thousands and thousands of miles over months. And the entire time, you know, with this giant calf in their uterus, to get to these warm safe bays in Baja, and the entire time they're fasting. So not only is she a growing this baby, but then she has to give birth to this baby and then she has to lactate and feed this baby, and the entire time she's not eating herself. And then at that point where she's just absolutely energetically spent that now she has to migrate back thousands of miles slowly with this baby, to get to a place where she can feed. I just think that's so miraculous. I mean these are just, you know, mothers that are so amazing and I'm just inspired by them every day.

Although not commonly perceived as such, alligator mothers are very caring towards their young. After spending 9-10 weeks protecting her eggs, she stays with the hatchlings for at least the first year of their lives. (Photo: Matthew Paulson, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Now, you've been a wildlife biologist and a conservationist for more than a decade. Are there any sort of magical motherhood moments that you've experienced in that time?

NEILS: Yeah, I have a very special moment where we are down in Baja. And we actually witnessed a gray whale that gave birth and then very gently lifted that calf and you know, this is a massive calf, it's close to 15 feet long, lifts it up to the surface to take its first breath. And when they're born, they're very floppy and the cartilage in their tail hasn't hardened yet. And so you know, they're very clumsy, they're not able to swim it takes a little bit of time and that mom is just so gentle, so compassionate, and just will kind of gently hold that baby to the surface, you know, encourage it to kind of try to swim around a little bit and then keep lifting it up so that it can keep taking those breaths. And it's just absolutely magical. And one of the the moments that actually inspired me to become mom was watching orangutans. So watching orangutans in Sumatra, and in Borneo, and just these mothers were just so loving and their whole world was that baby. And you know, everything that they did was was this baby and the moms would meet in the afternoons and they would all break down branches and make these like little platform nests, and bring their babies and the babies would play together and the moms would kind of rest and they would take turns looking after the babies so that the moms can each kind of get a nap. And it's just so lovely and so beautiful. And that was the moment I decided that you know, I wanted to become a mom, you know it was was watching that and feeling like I wanted to experience that.

BASCOMB: Absolutely. Aletris Neils is the executive director of Conservation Catalyst. Aletris thank you so much for your time today and Happy Mother's Day.

NEILS: Thank you so much for having me. I've really enjoyed it.

Related links:

- Watch a Grey whale giving birth

- Learn more about Aletris Neils

- National Geographic | “Why Animals "Adopt" Others, Including Different Species”

- Learn more about alligator moms

[MUSIC: Gregory Porter, “Mother’s Song” on Be Good, Motema Music]

CURWOOD: This year’s Goldman Prize winner from North America won a multimillion dollar settlement for her community. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Adam Ben Ezra, “Black Keys” on Intermission Album, by Adam Ben Ezra, adambenezra.com/shop]

Bringing a Plastic Giant to Justice

Diane Wilson in Lavaca Bay, Texas (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Diane Wilson is this year’s Goldman Prize winner from North America. Diane is a lifelong shrimper and fourth generation fisherwoman from Calhoun County on the Gulf coast of Texas and in the late 1980s, she started catching far fewer shrimp. At the same time, she learned her county was among the most toxic in the US. So, Diane started to investigate, and ultimately in December of 2019, she won a $50 million settlement from petrochemical giant Formosa Plastics for illegal dumping of toxic plastic waste. Formosa Plastics agreed to reach “zero-discharge” of plastic waste from its Point Comfort factory and pay for remediation of local wetlands and beaches polluted with their plastic waste. Diane Wilson wrote about her decades-long crusade in the book Diary of an Eco-Outlaw: An Unreasonable Woman Breaks the Law for Mother Earth. And she says today that despite all the pollution, the Lavaca Bay area is still home to rich biodiversity.

WILSON: Well the thing of it is there's upper Lavaca Bay and then it kind of flows into Matagorda Bay, which flows into the entire Gulf of Mexico. Bird species is one of the biggest places where people come down all over the country just to do bird watching. We got the endangered whooping crane, where they come to winter every year, we have the ridley turtles and we also are totally surrounded by we have Formosa Plastics, which is 17 units $7 billion worth, we have Alcoa aluminum that started in 1950. And we got the largest underwater Mercury Superfund site and the middle of it. So we've only got like 18,000 people in the whole county, but we've got a large fishing community. They're Vietnamese, they're Hispanic, they're working class fishermen. And these bays are the lifeblood, I mean, the communities are fishermen so it is their identity. And they are being literally destroyed because there's closures. There's signs, big signs all over the bay that says you can't eat fish, you can't eat the crab because of the levels of mercury in it. And then you've got Formosa Plastics that has been dumping plastic for 27 years. And the pellets, the plastic pellets are picking up the mercury and they're being dispersed all over the bays. And it goes down into the Gulf of Mexico and a little bit further on down the beaches toward Corpus Christi because along Padre Island they got all of these pellets washing up on the beaches, and they're like we're in a sand hill or these pellets come in from. And so you know, you can track it from these plastic manufacturers and Formosa makes a trillion pellets a day.

Diane Wilson kayaking with the Formosa Plastics compound in the background. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: That's a lot of pellets.

WILSON: It's a lot of pellets, a lot of pellets, and they've been known for 27 years.

CURWOOD: So what tipped you off to Formosa's connection to the pollution there in Lavaca Creek?

WILSON: Well, when I first started in 89, I absolutely knew nothing. I didn't know where Formosa was. I didn't know who they were, I didn't know the Taiwan connection. But when I asked for a meeting and started to get this tremendous backlash, you know, like I had state senator aides, I had bank presidents, I had economic development, and they were all coming down just trying to get me to shut up and not ask questions. And that's when eventually I had a reporter from Houston come down and he was amazed that nobody, anybody in Texas, with Congressman Phil Brown, down to the senators, down to the economic development, down to Chamber of Commerce, never asked a single question about Formosa's environmental record in Taiwan. And I mean, they were literally being kicked out of Taiwan. I mean, the people in there was so mad, they were throwing rocks at him up to Chairman Wong and he you know, he was getting his feelings hurt, so he was going to come down to Texas to Louisiana where they appreciated him. And so I started finding out their environmental record in Taiwan. And then I started having workers from the plant. I guess you could say, my key allies in this fight have been workers from the plant, because when a worker gets exposed when he has had enough, he's seen stuff, that's not right. He can't go to the plant because they will fire you. It's not organized, there's no protection. You go to local officials, they will tell you, well, we got a contract, the mayor's getting computer systems from them. You can't go to the state environmental agency, you can't go to the federal EPA, you can't go to OSHA, which is supposed to give them protection. So eventually, I'm at the bottom of the list, but eventually they come to me and that's when I really found out what Formosa was doing.

Pollution from plastic “nurdles”, small pellets manufactured by Formosa Plastics’ Point Comfort, Texas compound. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: Wait wait You're saying they came to you. What do you mean they came to you?

WILSON: I had Formosa workers that came to me and over the years, I've been doing this 34 years, I've probably talked to 100 workers. They were either exposed, they were sick, they were saw something that really outraged them and they had had enough. And you know, and some of it's been, like shift supervisors been there 25 years, it's been in wastewater, I have had upper management come to me, that's how bad it gets sometimes it's when you get started getting upper management that will come to you and tell you stuff. And I get documents, I get all kinds of memos and that's how you find out what's really going on in a plant. Because you ask industry and there's no work loss, there was no injury, anything that happened was worker error. That's a big one worker error. You know, and if there has been a spill, you don't hear it from industry, you hear from the workers. And I would get calls at midnight, I would get calls, wanting to meet in parking lots and wanting to meet and alleys. And you know, one time I was down in Corpus Christi, and I was at the state environmental agency, and I was kind of going through the boxes of information on Formosa. And I had these investigators that every once in a while they'd come in the door and look at me. And then finally one of them kind of said, come here, come here. And he took me to the filing cabinet, pulled out a file and said you do something with it. He said, it's real strange. I just goes to this bottleneck, and nothing happens. He said you do something with it. And you know, it was all the groundwater contamination under Formosa, which is extensive, but nothing happened. You know, and so I took all that information, took it to the county commissioners, took it to the county judge. And I mean, those commissioners were literally trying to run from me, they didn't want that information. So I've become quite good at being a private detective actually.

CURWOOD: Now, so nobody is going to help the county doesn't want to help, the state doesn't want to help, the EPA doesn't want to help. So how did you get action?

The Goldman Environmental Prize is awarded to six grassroots environmental heroes each year. Pictured here at the 2023 Prize Ceremony from left are recipients Tero Mustonen, Delima Silalahi, Alessandra Korap Munduruku, Diane Wilson, and Zafer Kizilkaya. The 2023 Recipient for Africa, Chilekwa Mumba, attended the ceremony virtually and is not pictured. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

WILSON: Mainly, believe it or not, and it wasn’t because I had an experience or had any political savvy, I started doing civil disobedience. I remember the first time you know like Formosa, it was the largest thing in Texas, ever. And they had all of these federal projects, they were going to give them all this text abatement, you know, all of this. And they were not going to have to do what they call an environmental impact study, like, how is this plant going to impact this community and this body of water Lavaca Bay? It was going to have to do it, you know and Formosa was like, we don't have to do it and the EPA was saying, we don't have to do it. And I was like, well, you know, and I had this activist out of Houston and he said, Diane, he said, the parades over, you're at the end, so just pat yourself on the back and say you did a good job, but it's over. You can't do anything. And I said, they're not going to get that body of water. And he said, You can't do nothing about it. And I said this off the top of my head. I said, I'll do a hunger strike. [LAUGH] And he got the biggest kick out of that laughing He said they don't do hunger strikes in Texas. They might in California, but they sure don't do them in Texas. And I said, I don't care. I'm doing a hunger strike. And I know enough about human nature and myself that if I did not do that hunger strike, right then. I mean, I'd go to sleep that night, wake up in the morning and say, boy, that's the stupidest thing you ever thought of. And so I immediately got ahold of a reporter and said, I'm starting a hunger strike. And she said when and I said right now. And so I started a hunger strike, it was the first one and I didn't know how to do it. I didn't have a cell phone, I did it on a shrimp boat and the only one who really knew I was on a hunger strike was Formosa. And every day this, he was regulatory affairs at Formosa. He brought down all these engineers and suits and did get bring him down there and they'd look at me and then he'd say now, isn't she a stupid woman? And then he'd say, oh, Diane, please get off this hunger strike, get off the hunger strike. And I stayed on the hunger strike. And believe it or not, two weeks on a hunger strike, with very little support, almost no media and I won it! The EPA made Formosa do an environmental impact study.

Diane Wilson untangling rope on a shrimp boat at Seadrift Harbor. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: Ahh.

WILSON: So it turned the whole thing around and it stalled everything. All of the federal agencies got involved, the public got involved. And so, you know, it didn't stop them but it definitely stalled them enough that people could get involved. And so that was a good thing. And that's when I realize how powerful and changing things that civil disobedience could be. So predominantly, that's how I did stuff down there is through civil disobedience.

CURWOOD: I gather ultimately, the environmental impact statement that the EPA put together was not enough to stop Formosa.

WILSON: Oh, goodness, no goodness, no.

CURWOOD: So what did you have to do to stop Formosa?

WILSON: Well, the thing is, Formosa is still, you know, they've got permits are still discharging. I did a lawsuit with the help of a legal aid group and they did environmental work and so I hired them. And me and a couple of the workers from the plant we collected all this evidence that Formosa was discharging all of this plastic and powder, and they never admitted to it. They flat told to my face, they had never discharged a single pellet. I mean, I mean bald faced lie. So we collected all the information. We documented it. We did probably 2,500 samples. It took two and a half years of documentation. I took 8000 photos and videos, and we went to court and we won.

CURWOOD: Let me ask you, when you were documenting their pollution, how did you gather evidence of their illegal release of of these plastic bits, these nurdles?

WILSON: You had no knowledge of it, so you had to just go looking for it and we knew it was out there. So I had to kayak, I kayaked all over that place. I finally found every single stormwater outfall and some of these outfalls are big enough that you can land a helicopter in them. And to get a sense of the volume of them, is that in discovery, I found one of Formosa's releases out of one of the stormwater outfalls which is not supposed to have anything but water in it and they had released 167,000 pounds of pellets in one day at one outfall, and for most has been doing this for 27 years.

CURWOOD: What's going on here, how is it that a plant can be discharging this much plastic?

WILSON: Well the thing that is I think most people have no idea what these plastic plants are really releasing it's like Formosa's got 16 units and you have packaging, you have them putting on trains, you them have putting on trucks, and almost at every point in that process they're losing thousands of pounds of plastic. And then you have the powder. I mean the PVC powder, the polypropylene, the polyethylene, and I know I had a worker that was on the SPDC Specialized PVC Powder and it was a five story building and he sent me photos from inside and it looked like a blizzard and powder went all the way up to the fifth story it was open, it was in the fields. It's it's everywhere, it was everywhere, they lose it everywhere.

Diane Wilson kayaking among the Formosa Plastics remediation site. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: How are the cancer rates?

WILSON: Oh my god, there was so much concern about the workers in the vinyl units, which is around the plastic of brain cancer. They were even scared to go to the doctors because they thought they had brain cancer. It was so much of a concern that even the management got wind of it. And so they sent out a memo and they're like to all the vinyl chloride workers who are concerned about brain cancer from the vinyl chloride exposure and they were sending down a doctor. And so they presented the vinyl workers with a study that was by the American Chemical Council and the Vinyl Institute and it said there is no harm in vinyl chloride exposure to brain cancer and you guys, just do not worry about it. But it's rampant cancer is like all of these guys have got, you know, all the ones that I work with, all of them are sick and got neurological damage to their legs and their arms and it's a very sad state of affairs. That's a big problem on the vinyl chloride exposure and EDC and the benzene and all of that, it's rampant.

CURWOOD: Formosa Plastics has been trying to put up a plant in Louisiana.

WILSON: Oh, that's true. That's true.

CURWOOD: Local folks have been pushing back against that and Formosa right now is on the negative side of various rulings. Any advice to the communities that are fighting Formosa there?

WILSON: Yeah, I would tell them the one thing you know, I've been doing this 34 years and the one thing I regret was that I did not try harder to stop them completely. They have no idea how it would change their community, like the community of Point Comfort for Formosa is that it started out like 1400 people, a school all of this, now it's down to 600 people, because the majority of the people left and wanted to get away. The school closed down, and now it's Formosa's training center. So it is like Formosa from one end to another, the landowners next to them that have been there, the ranchers that had been there for 160 years, Formosa bought every single one of them out. Just you know, they just acquired 2500 Acres. It's like a steamroller and it will roll them down and destroy the community.

Diane Wilson speaking at the 2023 Goldman Environmental Prize ceremony. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: So what keeps you going? I mean, you're dealing with a multibillion-dollar corporation that, you know, they have phalanxes of lawyers. They have apparently, as you say, you suggest everyone from the local county politicians right on up through federal elected representatives support them, what keeps you going?

WILSON: I'm a fourth-generation fisherwoman, my family's been here around 130 years, I've been on a boat, the back deck of a boat since I was eight years old and I would say I have bonded with that bay. When I was really little and I would go down the bay to see my dad come in and bring in the shrimp and all the boats and all of that it's like I literally could see this old woman down there and she was always glad to see me and this personality that she had. And you know, and and I remember maybe a few years later when I realized is ,that old woman was water. I literally could see her, so the water to me is real, it's alive, it has value, it's family, and it's like I will not let them get that bay. I will not do it. I can't I can't it's it's probably the best part of myself.

CURWOOD: Wow I want to thank you Diane Wilson, winner of the North American Goldman prize of 2023.

WILSON: Thank you very much. I appreciate it very much.

Related links:

- Learn more about Diane Wilson

- Listen to our previous 2023 Goldman Environmental Prize interview

[MUSIC: Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, featuring Matraca Berg and Emmylou Harris, “Oh Cumberland” on Will the Circle Be Unbroken, by Matraca Berg/Gary Harrison, Capitol Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – we continue our celebration of Mother’s Day with a memoir of learning from what are called mother trees. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jimmy Smith, “Blue Moon” on The Sounds Of Jimmy Smith, by R. Rodgers - L. Hart, Blue Note Records: RVG Edition/Music From EMI]

Beyond the Headlines

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has set aside six new Indigenous reserves in the Amazon rainforest, restricting logging and mining on 1.5 million acres. (Photo: Alberto César Araújo, Amazônia Real, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

And on the line now from Atlanta is Living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra, with a look beyond the headlines for us. Hi there, Peter, how you doing, and what you got for us?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. Got a story that sounds like political and ecological good news out of Brazil. Brazil has been whipsawed on environmental policy as much as any nation in recent years except maybe for the United States. And when President Jair Bolsonaro, also known as the Brazilian Donald Trump, was voted out, his rival Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva was voted back in. Lula established recently, six new Indigenous reserves in the Amazon. A million and a half acres, it's a lot of area, bigger than some American states. There'll be no mining there, and big restrictions on both logging and agriculture, the things that have begun to completely obliterate the greatest rainforest in the world.

CURWOOD: Yeah, and under Bolsonaro, there was a huge increase in deforestation, paying no attention to the fact that this forest helps us mitigate climate change by sequestering carbon and such.

DYKSTRA: Climate change and overall biodiversity, there is no place in the world like the Amazon. And Lulu da Silva is positioned to be its political savior, as well as the indigenous tribes that live there will be, as has been the case for thousands of years, the custodians and keepers of these ecologically valuable areas.

CURWOOD: Right, Peter, they certainly have the knowledge. Hey, what else do you have for us today?

The Washburn Fire was a human-started forest fire that burned in Yosemite National Park in July 2022. (Photo: Anonymous, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: We have another area where the knowledge has not so much been respected. You know, Yosemite, like all national parks came into being and all of a sudden, the government was in charge of land management. And in the case of Yosemite back in 1890, that meant in many areas that neighboring tribes were no longer in charge. And one of the things that went away is the periodic prescribed burns that had been part of the tradition of the tribes around Yosemite. And when they went away, gradually big wildfires became more common. There was a huge wildfire in July, and it destroyed not only homes, but destroyed a whole lot of forested areas that were no longer protected by the traditional ways of protecting land and preventing fires.

CURWOOD: But we do know that the native folks who live there presumably for thousands of years, had it all managed with small prescribed burning from time to time.

DYKSTRA: Thousands of years of knowledge put up against a little bit of knowledge and a lot of power all suddenly by the government. Native knowledge wins out every time, except when it's not allowed to prevail. And that's been the case near Yosemite.

CURWOOD: So let's take a look now at your history books, and tell me what you see.

This painting by Albert Bierstadt, Gosnold at Cuttyhunk depicts Bartholomew Gosnold’s ship, the Concord, during his May 1602 voyage where he named Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard. (Photo: Albert Bierstadt, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: I see Bartholomew Gosnold, back on May 15, 1602. Not one of your more famous European-based explorers of North America, but in his own right, he was a big deal, even though he wasn't really an explorer per se. Bartholomew Gosnold was more of an attorney for explorers. But in 1602, he took a ship called the Concord into Provincetown harbor at the tip of Cape Cod. And they had caught what he called 'a great store of cod'. And that named that peninsula 'Cape Cod'. Gosnold, also named Martha's Vineyard. And a few years later, he was the explorers' lawyer in the exploration and founding and colonization of Jamestown in Virginia. The same year that they got there, Bartholomew Gosnold died, fulfilling the wishes of many people about many other lawyers throughout the centuries. But he did leave his mark, both in New England and in Virginia.

CURWOOD: And even today, just off of Martha's Vineyard is a little island called Gosnold. Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is a contributor to Living on Earth. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve. Thanks a lot, and we'll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth web page. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- EcoWatch | “Lula Recognizes Six New Brazilian Indigenous Reserves”

- The Los Angeles Times | “This Tribe Was Barred from Cultural Burning for Decades — Then a Fire Hit Their Community”

- Learn more about Bartholomew Gosnold’s naming of Cape Cod

[MUSIC: Lemmen wiJan (johandegreyze) and Ernst Burns, “Old Cape Cod”]

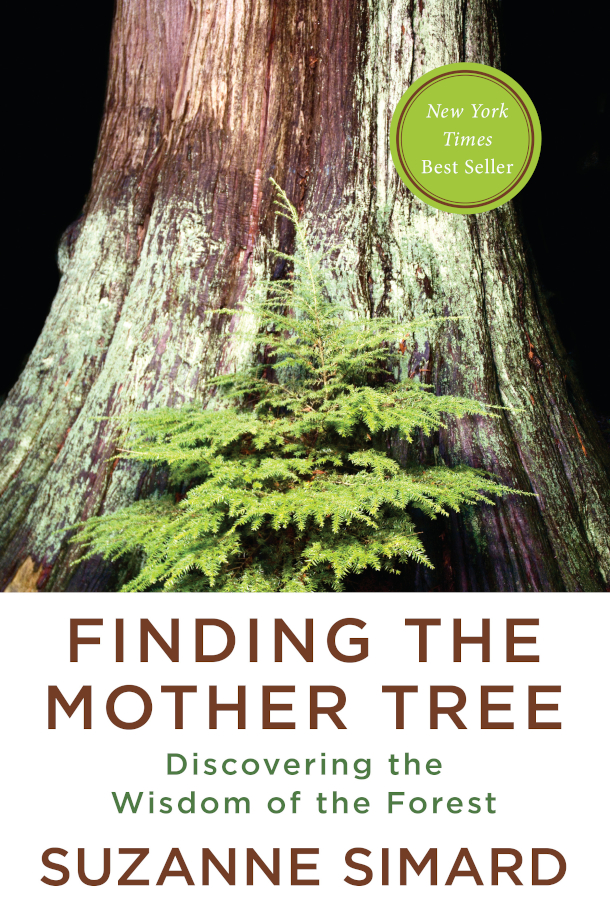

Finding the Mother Tree

“Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest” takes readers into the field with Suzanne Simard as she describes her forest experiments and shares how her findings helped her through the challenges of motherhood and a cancer diagnosis. (Photo: courtesy of Knopf)

CURWOOD: At the top of the show we talked about mammal mothers.

Now we consider the mothers known as mother trees. Ancient trees are crucial to the health of a forest. And they can communicate through networks of soil fungi called mycorrhiza. Ecologist Suzanne Simard found that trees can send warning signals and additional nutrients to their own offspring in greater amounts than to unrelated trees. Suzanne wrote a book about her ecological discoveries that is also a memoir about her own experience of motherhood as well. It’s called “Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest.” She teaches forest ecology at the University of British Columbia and spoke with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

DOERING: So, you just really have this way of looking at a forest and seeing so much more than I think most of us ever do. Where do you trace your connection with the forest back to?

SIMARD: Well, I grew up in forests. So you know, I live in a province of forests in British Columbia, and there's so many different kinds, but I grew up in what are called the inland rain forests, beautiful, huge trees, cedars, and hemlocks, Bruce's larches. birches, it's very, very species diverse forest for the Pacific Northwest. And so I grew up there, my great grandfather, my grandfather, my dad and uncles were all horse loggers, and seeing how, you know, how to live in forests and make a living out of it without actually destroying the forest.

DOERING: It sounds like understanding the forest being in the forest is in your blood.

SIMARD: Yeah, well, it is. It's also in my DNA, because it was like multiple generations of families doing this, our family doing this. So yeah, I kind of grew up with it in my background, and my blood, my bones, my DNA.

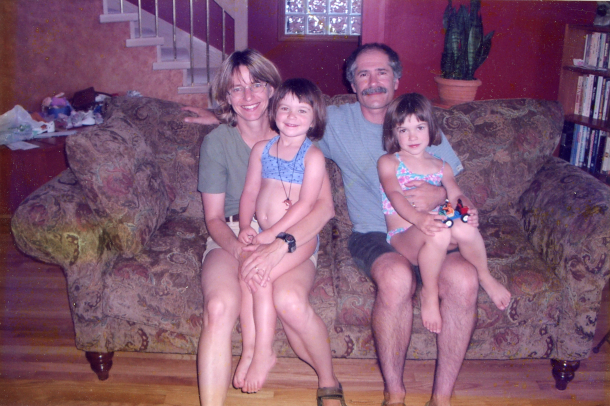

DOERING: Well, what got you curious, in a scientific way about the connections between trees and the rest of the forest?

Simard grew up in the forests of British Columbia and often camped with her family. Left to right: her brother Kelly, three; sister Robyn, seven; mother Ellen June; and five-year-old Suzanne. (Photo: courtesy of Suzanne Simard)

SIMARD: Yeah, so after I grew up, I became a forester, myself. And when I entered into the forestry profession, at the age of 22, I started to learn that, you know, when I grew up with my grandfather, horse logging wasn't at all what the forest industry had become. It had become, you know, this clear cutting machine that wouldn't just take out the odd tree here, and there wasn't selective logging, it was clear cut logging. And that means, you know, taking every tree out, and my job at the time was to replant these forests, with trees, seedlings and try to help them recover. But what I found was that, you know, when you don't have you know, surrounding trees, and good soil, that it's harder to get trees growing. And so I saw this and the practices that were getting hold like herbiciding the native plants to get rid of them to make way for these trees that we were planting to give them a better shot at sun and light, and water, actually was having, you know, a detrimental effect on the trees. So the trees actually seem to need these native plants around them as part of their successional process of, you know, healing the land. And that was that what I was seeing that started to get me to look below ground at what we might be doing wrong.

DOERING: So you noticed as a forester, when you were trying to help these plantations succeed, you noticed that they just weren't regenerating very well. They weren't healthy. They didn't seem like they were going to survive. How did you then go about trying to figure out what could help them survive?

SIMARD: Yeah, so one of the things I noticed, you know, some trees would do really well, but others would suffer from pathogens and insect infestations, and especially a root pathogen was infecting a lot of the Douglas firs and it would spread from fir to fir to fir and affect the whole plantation. And so I thought, well, if it's a root pathogen, I need to look below ground at what's going on here. And these root pathogens, these fungal pathogens, really were attacking the big roots of the trees and then girdling them in other words, infecting the base of the tree, and then they would just die within a year or two. And so I thought, well, we're disrupting the soil balance. So I started looking at the fungal communities below ground, there's thousands of species of fungi, you know, there's kind of three or four main groups: there's pathogens, like I mentioned, that kill trees, there's saprotrophs, which decay stuff, and there's mycorrhizal fungi, which are helper fungi. Which by the way, mycorrhiza literally means fungus root. It's a relationship, a symbiotic mutualistic relationship between trees and fungi, where the tree provides photosynthate or carbon energy to the fungus. The fungus then uses that energy to grow mycelium through the soil. And as it does that, it kind of coats all the particles and soil pores and draws out the nutrients and delivers it back to the plant or the tree in exchange for this photosynthate. So they both are benefiting from this. And I learned in my research that these fungi can actually connect trees together, they can connect trees of the same species, they can even connect trees of different species. And I found out that in my research that paper birch, which was a target of these herbicide treatments, because it's shading the fir.

A clearcut in British Columbia. (Photo: meaduva, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

DOERING: It's a competitor.

SIMARD: Yeah, as a competitor, that it actually was connected to Douglas fir, and delivering carbon to Douglas fir, which, you know, we hadn't thought of that before. And that kind of changed the equation then like it's not just a competitor. It's actually also a collaborator at the same time.

DOERING: What could your discovery of how carbon moves between trees with the help of fungi mean for our climate change efforts?

SIMARD: Lots and lots. So for one forest cover a third of our terrestrial land base, they contain about 80% of our terrestrial carbon. And so they're hugely important in the carbon budget. And of course, we know carbon is sort of, you know, a key indicator of climate change. And so forests are important in this, anything that happens to forests affects the global carbon budget. And we are affecting our forests every single day. What my research shows is that keeping these old forests, these old trees, the mother trees, which are sort of the linchpins, or the nucleus of the recovery of forests from any kind of disturbance, whether it's fire or logging or insect infestations, these old trees are essential in the recovery of the forests in the regeneration of the forest. But they're also really important because these old forests, especially old growth forests, which are you know, basically the most ancient forests, they store so much carbon in the soil in their trunks. And they're also rich in biodiversity, the fungi in the soil, they support the lichens in their crowns, the birds that use them and the animals, so on these old forests are hubs of biodiversity. But we're logging them at this incredible rate right now. In where I live in British Columbia, we really only have 3% of our valley bottom, huge old growth forests left. And this isn't just happening in British Columbia, it's happening around the world. The other thing that my research shows is if we're going to log, which we're going to continue to do, but we can focus our logging in areas where it's not so impactful on biodiversity and carbon budgets. But where we do it, to leave the old trees behind, you know, don't just take them because that is, you know, historically, that's what we've done. We, we high grade the biggest trees, but it turns out, they're the most important trees in the recovery of the ecosystem. So the harvesting shouldn't be clear cut harvesting, like we're practicing worldwide now, it should be selective harvesting. It should be leaving these old trees behind to facilitate the recovery of the forest.

As a young forester, Simard noticed that the seedlings planted after a clearcut were often sickly, and her observations prompted a whole career of research on mother trees. (Photo: © Bill Heath)

DOERING: So you write, that these fungi that connect trees in a forest might be able to evolve and adapt much faster to a changing climate and help the trees adapt too. So how could that work?

SIMARD: Yeah, that's a great question. Um, so you know, trees, of course, they're the foundation of the forest. They're photosynthetic. They're what links carbon in the sky to carbon in the soil, they convert light energy to chemical energy and drive all of our cycles. So whatever happens to trees, happens to all of us. And so really, to keep the biosphere in balance, we need to maintain forest cover across the globe. And we're losing it really quickly, you know, not just because of logging, but wildfire and insect infestations that are driven by climate change. And so trees are not going to be able to migrate or adapt as quickly as they need to, to keep up with the velocity at which climate is changing. So what is their other choice? Well, a lot of them are going to die. And we're seeing that. And yet, you know, because you know, evolution and trees take so long but evolution and fungi doesn't take as long fungi have a shorter lifespan, right, they reproduce within a year, they can mutate and be different from one year to the next. And so they can actually serve as an interface between the rapidly changing climate and the more slowly changing trees. And so the one way that we can sort of capture that adaptation or adaptability of the fungi is to make sure that trees have their appropriate microbiome, which is the fungi, the bacteria that have short lifespans, short life cycles are healthy in the soil. And that can help the trees survive, and possibly migrate a little bit further. The other thing that we need to do though, is we need to assist the migration of trees and the fungi, to keep up with the velocity of climate change to make sure that in the new environments that they're in, that they're able to cope as best as they possibly can.

DOERING: Your book, "Finding the Mother Tree" is also a memoir. How does your quest to understand mother trees resonate with your own experience of motherhood?

Simard and her family in 2005. (Photo: courtesy of Suzanne Simard)

SIMARD: That's a great question. So I wrote the book because I wanted the science to get out. But I also wanted to show that science is such a personal journey, right? It's not something to be distrusted. It comes from us. It comes from our hearts, it comes from our curiosity, to make sense of our world. And, you know, the work that I did was a reflection of my life. And so I started, the questions that I asked came from my experiences in the forest, but also as a mother, myself, and I found that the trees told me about motherhood. And I informed my research about looking at motherhood in forests, or the role of nurturing and forests, because I was going through that myself. And the role of, for example, sickness as well, I had breast cancer and I wanted to understand what if an old tree is sick and dying? What happens? Is there a connection with their kin, their children? And can that inform how I'm going to respond to this? And so, actually, when I got breast cancer, I set up a series of experiments with my graduate students saying, What if a mother tree is sick? What if she's injured? What if a mother tree is dying? And we found that these dying mother trees would actually send warning signals to her own kin more so than strangers, as well as provide more carbon energy to those kin seedlings so that they could grow bigger networks and grow healthier and stronger. And that sort of was a way of those trees of passing on their life energy into the next generations. It's a very Darwinian, in a way, it's survival of the fittest. Honestly, I don't think I would have asked those questions if I hadn't gone through this experience myself. The trees have taught me so much. And of course, when I learned this, I was already, you know, passing things on to my kids in case I didn't make it. And then I did make it, but I learned a lot about, about the importance of, of where to put your energy when the stakes are really high.

Suzanne Simard has published over 200 peer-reviewed articles and her work has influenced filmmakers (the Tree of Souls in James Cameron’s Avatar). Her TED talks have been viewed by more than 10 million people worldwide. ( (Photo: © Diana Markosian)

DOERING: Before you go, Suzanne, what you've been able to uncover in the forest is really profound, these deep connections between all the species in the forest. You say that we don't have to be a forestry scientist to deepen our own connections with the natural world. So how can we try this at home?

SIMARD: Yeah, I mean, there's so many things you can do. So I mean, the first thing is just being reconnected with your trees, your plants, what you have around you, most of us have access to some kind of natural plant community, and just being with them helps you to reconnect. And when you get that connection back, then you'll fight for the forest. So that is the absolutely the first step. You know, it's like falling in love. You know, once you fall in love, you care for that person and you keep, you know, you nurture that relationship. It's the same thing with your connection with forests. And then from there, the actions you can take, of course, you know, you can make choices like don't buy, you know, furniture that's from a tropical tree that's endangered, try to reduce your consumption of cardboard and toilet paper and paper products, making choices as a consumer. And that sends a strong message to the companies that are logging forests, you know, making sure that they're sustainable practices. And you can do that by looking at you know, certification, which has its own flaws, but in a sense, you have a lot of power as a consumer to boycott those companies that are basically mining forests. And then of course, the next step is to become beyond that is to become active in the change itself, the change makers, the ones that are on the lines, maybe a protester, or maybe a writer, or you know, doing interviews like this, those are all important steps as well. Getting the word out educating, getting people aligned so that we all care and fight for our planet because we need it to survive.

CURWOOD: Suzanne Simard is a professor of forest ecology at the University of British Columbia and the author of "Finding the Mother Tree." She spoke with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Related links:

- Find the book “Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest” (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Author Suzanne Simard’s website

- Learn how to get involved with the Mother Tree Project

- Watch Suzanne’s popular TED talk, “How Trees Talk to Each Other”

[MUSIC: Shubh Saran Hmayra, “Haze” on Hmayra, Art of Life Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Fern Alling, Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Jusneel Mahal, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth