The Great Displacement

Air Date: Week of May 26, 2023

“The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration” is the new book by Jake Bittle. (Photo: Courtesy of Simon and Schuster)

Climate change is already making some places across the country unlivable and seems likely to uproot millions of Americans in the coming decades. Journalist Jake Bittle collected the stories of people across the U.S. who have been driven out by fires, floods, droughts, and extreme heat. He joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss his new book, “The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration.”

Transcript

CURWOOD: Climate change is bringing more than just painful discussions about water use. It’s already making some places across the country unlivable and seems likely to uproot millions of Americans in the coming decades. That’s the focus of journalist Jake Bittle’s new book, “The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration.” He collected the stories of people across the US who have been driven out by floods, fires, droughts, and extreme heat. Jake Bittle joined the Living on Earth Book Club at a live event at UMass Boston to share his insights on this radical reshaping of American geography. I asked him how his project began.

BITTLE: So before I wrote about climate change, I mostly wrote about housing, and I had learned about a federal government program in Houston, where the government paid people to leave their homes, and they knocked down homes that were perennially flooding. You know, they'd flood ten, twelve times, in as many years. And I went to Houston to write a magazine article about it, and I walked around these neighborhoods that had been completely emptied out, you know, in the middle of a relatively dense city. And I was mostly writing about the people who had hung on and, you know, not participated in the program, and were staying in these empty areas. But during the course of writing that article, I sort of started to wonder, 'Where did all the people who took the money end up?' And almost nobody could tell me. FEMA couldn't tell me, Houston couldn't tell me, the neighbors couldn't tell me, maybe there was one academic who had tried to find it out. And that was the seed for the book was I used the federal database of buyouts and then I used the white pages to find all the people who had lived in these homes before. And I ended up with maybe ten, or twelve times as much material as I was able to use in the article and it quickly became clear to me that it wasn't a problem that was localized to Houston, it wasn't a phenomenon that was specific to flooding. It was a sort of very unremarked upon or poorly understood movement that was going on after these disasters all over the country. And that was kind of the initial idea for the project.

CURWOOD: What did the people who stayed think? It's like more than a thousand bucks a month to pay for insurance for the place which probably the mortgage payment itself...

BITTLE: It's much less than that.

Jake Bittle is the author of “The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration”. (Photo: Jasmine Clarke)

CURWOOD: Could be less than that in many of these places.

BITTLE: Yeah.

CURWOOD: If they saw this devastation, why did they stay?

BITTLE: Yeah, it's a really, really good question. It's always a very messy topic, you know, movement decisions and migration, people don't really act, always, in the ways that we expect them to. It seems to be different for each person, but I think there were sort of two reasons. One was that people really have a really, really strong attachment to the place that they're from, and in a lot of cases, there just isn't another part of the country, or indeed, the world that is similar, and everyone they know lives there, that's where they work. You know, they had had insurance so they were able to rebuild after a flood. And they just thought, 'Well, you know, I don't want to leave, there's not really anywhere else I can go that's as affordable as this neighborhood.' The other side of it, though, is that it's really hard to find somebody to buy your house if you want to sell it. So there's a separate piece where the homes become albatrosses. What you'll see is a lot of people who are stuck, you know, they basically have no option but to sort of plead at a political level for what in the book, you know, I think I describe fairly as a bailout, it's not their fault for living there, but the only solution, realistically, is for the government, you know, which doesn't have a stake in it, to pump money in to get people out of their homes. And the government, I think, has to act as a backstop in the same way that the Federal Reserve does for banks. You know, FEMA, or whichever branch you prefer, can act as a backstop for the housing market and just say, 'Look, the only realistic solution is for the government to intervene because the market has just completely broken down.' So yeah, you have then people who are in love, or they're trapped, you know, and sometimes they're both.

Climate change is causing more frequent flooding events (Photo: Staff Sgt. Daniel J. Martinez, Air National Guard, Picryl, public domain)

CURWOOD: Yeah, talk to me about insurance in a place like Norfolk, Virginia, say.

BITTLE: Yeah, so most people there for flood insurance, they purchase a policy from a federal government program because most private companies don't offer it because it's not profitable. But those policies are getting extraordinarily expensive. I'd spoke to several families who are paying upwards of $13,000 a year for policies, that's more than 300 times what it was a couple of years ago. And there's not really a cap on that. And I think it's interesting, because what the policy, what that number is trying to communicate is that, you know, one day the home will be potentially permanently underwater. So its value is essentially nil. And the cost of protecting it is infinity. So that number, which is impossible for families to pay, is sort of communicating, like, the financial system of homeownership can't sustain you living here. But for the people in that position, it just feels like a massive, you know, financial burden and often leads to them having to, to leave.

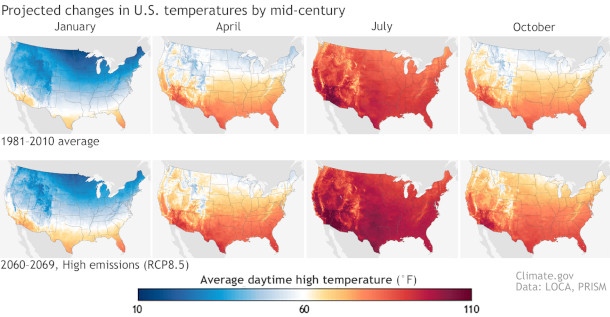

CURWOOD: You know, you reveal in your book that the major cause of truly regional migration isn't necessarily that sudden weather event, the flood, or the hurricane, the fire, but the gradual increase in temperature. Why is that?

BITTLE: I think that it's because of the way that people experience risk, right? I think that, you know, the chances that my town is gonna get hit by a hurricane each year, they're always going to be relatively low, it's never going to be 100%, right? And you can always kind of say, 'Okay, well, you know, maybe this flood insurance payment is too high in this home, but what if I move to higher ground, you know, just a couple miles away,' right? 'And get a discount on my premium.' But I think the idea that every summer, you're going to face lethal temperatures, right? There's health impacts, it's extremely dangerous to raise children in that kind of weather. I think that is what's going to make people make this psychological decision to make an elective movement away from these areas and away from the regions as a whole, right? Because of the way that we've built our cities and, you know, because of the way we've built against rivers and mountains, there's always a place that's more resilient to flooding or fire than, you know, a place 10 miles away. But heat is a, you know, it's an atmospheric phenomenon, it's not something you can avoid, just by moving a couple miles away, you have to move to a place that's more temperate, and even then you're not totally out of danger. So I think that that's the kind of thing is, it's not really a financial burden, people won't experience it financially. It's not even necessarily, you know, like something that's going to damage their property. It's just the feeling of 'Okay, as long as I live here, I'm going to have to deal with this.' That's going to change a lot of people's minds, I think, especially when you look into the health impacts on older people and very young people.

Sea-level rise is causing storm surge to flood coastal infrastructure more, leading to more damage and higher insurance premiums (Photo: pxfuel)

CURWOOD: And what about businesses? I mean, business and industry is going to have to migrate.

BITTLE: Right, certainly. I mean, look at, you know, San Francisco, for instance, a lot of tech companies have said, you know, 'Our workers don't want to come to work, they don't want to live here, because they're concerned about crime, they're concerned about quality of life,' and it turned into a hair-pulling moment for the industry. It's not that hard to imagine all the tech companies, for instance, that are being headquartered in Austin, right now, a lot of them have moved to Miami, it's not that hard to imagine them saying, 'Uh-oh, our workers don't want to live here, because it's far too hot. We have to make sure that we move our offices somewhere else so that we can attract talent.' You know, it's not happening yet. But it's it's far from implausible.

CURWOOD: So, the subtitle of your book includes migration, 'the Next American Migration.' Where are people going? If they figure out they have to leave?

Global warming will cause regional migration as some areas begin to see lethal temperatures every summer (Photo: Rebecca Lindsey, Climate.gov)

BITTLE: Yeah, if you look at a map, and you sort of assess on paper, what are the places but the least vulnerability to hurricanes, storm surge, sea-level rise, wildfires, drought, etc, you end up with a list of cities, mostly in the Upper Midwest, right? Cincinnati is often put forward as a potential place because it could house twice the number of people that it currently does, it has an abundant supply of fresh water. Buffalo for all its many weather issues is often said to be like one of the most resilient places to climate change. I think that, you know, the fate of coastal cities like Boston, whether they become moving sites for people really depends a lot on how much we spend on ensuring that they're resilient to the biggest disasters, right? So there's a version of Boston, where there's a giant green ring around the waterfront and it's really, really difficult to imagine a storm big enough to flood the city. You know, that's definitely possible. But it's sort of up in the air, I think. But there are places that are sort of ready-made for this right? Duluth, Minnesota, Chicago to a certain extent, that those may be the places where, if you were making a hypothetical decision about where to put your money, you might end up there, right? But that doesn't imply that people will make such rational decisions. It's just like, on paper, they look good right? You know? I think what's important to emphasize is it doesn't necessarily need to involve people from the South picking up their things and moving north. In the short term, they mostly go, I think, the shortest possible distance that they can, right? A lot of times they end up moving into another place that's just as vulnerable, or they move to the closest city where they can find cheap housing, right? So, sometimes they'll move from a rural area to a nearby city, you know, anything to maintain the social ties that they already have. You're not seeing a, you know, a march north or a movement west on the scale of the Dust Bowl, but you are seeing people start to say, 'Okay, well, there's certain areas, often rural areas that are extremely high risk and don't have enough money to keep up with the pace of disaster.' And then so the locus of investment and growth will gradually shift to the north I think. But it can take a while and I think the rest of the country has to look even worse than it does now. And that may not change for, you know, a few decades until you start to see some really devastating and chronic events.

CURWOOD: That’s Jake Bittle, author of The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration. You can watch the full video of our live event with Jake Bittle at loe.org/events.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth