May 26, 2023

Air Date: May 26, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

ExxonMobil Sued in Guyana

View the page for this story

Guyana has one of the fastest growing economies on the planet as an offshore oil boom gets underway. But a potential spill could wipe out its fishing and ecotourism economy. So, a trial judge recently ruled that a major ExxonMobil crude oil project needs to provide an “unlimited guarantee” to cover the costs of such a spill. Journalist Amy Westervelt of the Critical Frequency podcast joins Host Jenni Doering to explain the ruling and Exxon’s oil development in Guyana. (13:03)

Less Water for the Dry West

View the page for this story

The states that rely on the Colorado River for water are facing a supply crisis as climate change reduces the river’s flow. Now, after months of tense debates and delay, California, Arizona, and Nevada have finally agreed to substantially reduce their Colorado River water use, at least for now. KUNC reporter Luke Runyon joins Host Jenni Doering to explain the deal and the federal help these states will receive to ease some of the economic pain of cutting water use. (08:45)

The Great Displacement

View the page for this story

Climate change is already making some places across the country unlivable and seems likely to uproot millions of Americans in the coming decades. Journalist Jake Bittle collected the stories of people across the U.S. who have been driven out by fires, floods, droughts, and extreme heat. He joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss his new book, “The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration.” (09:43)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about Montana’s new law that blocks climate concerns from permitting decisions. Also, Bisphenol A or BPA is linked to cancer, obesity, and diabetes. Now private researchers say significant levels of BPA can be found in some sports bras and other athletic clothing. And in history, they look back to the creation of the Nobel Prizes. (05:05)

Note on Emerging Science: How Lizards Can Breathe Underwater

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

Some anole lizards can stay underwater for up to 20 minutes to evade predators, and now researchers have discovered their secret. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman reports that these lizards use a bubble of air around their snouts and rebreathe the bubble in and out. (02:00)

The Life of a Dead Whale Fall

View the page for this story

When a whale dies, it eventually sinks to the ocean floor. And although that whale’s life is over, that’s when a whole new circle of life kicks off, with thousands of organisms including hagfish, zombie worms, and octopuses feeding off this “whale fall” for 50 or more years. Children’s author Melissa Stewart wrote about this ecosystem in her book, “Whale Fall: Exploring an Ocean-Floor Ecosystem,” and joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss. (07:33)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230526 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jake Bittle, Luke Runyon, Melissa Stewart, Amy Westervelt

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

Guyana is ramping up oil drilling even as climate impacts loom.

WESTERVELT: 90% of Guyana's population lives on this narrow sliver of coast that is predicted to be underwater by 2030, so in this really kind of horrifying way government officials talk a lot about how they need this oil money to pay for climate adaptation.

CURWOOD: Also, the weird, wonderful world of whale fall.

STEWART: So I came across zombie worms, which are also known as bone-eating snot flower worms. The females are about 1 or 2 inches tall – they live on the bones of the whales as they’re decaying, but the males are microscopic, and they live inside the female bodies.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

ExxonMobil Sued in Guyana

Exxon’s offshore production vessel off the coast of Guyana. ExxonMobil and its partners are expected to produce more than 1 million barrels of oil and gas per day by late 2026. (Image: Courtesy of ExxonMobil)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Since the discovery in Guyana back in 2015 of an estimated 11 billion barrels of oil off its shores in the Caribbean, the South American nation now has one of the fastest if not the fastest growing economy on the planet. The international monetary fund estimates Guyana’s GDP will grow close to 60 percent this year, thanks to Exxon Mobil and its partners pumping more than a million barrels of crude every day. But environmental concerns, spotlighted by the numerous oil spills suffered by its oil-rich next door neighbor Venezuela, prompted two Guyanese citizens to file suit in 2021. They allege the government’s deal with Exxon violates Guyana’s responsibility to protect the right of its citizens to a healthy environment. The trial judge sided with the plaintiffs and ordered Exxon and its local subsidiary to provide a quote “unlimited guarantee” to cover the costs of cleaning up a catastrophic oil spill like the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon disaster. To learn more about this ruling and Exxon's oil development in Guyana, we’re joined now by Amy Westervelt, an investigative journalist and executive producer of the independent podcast production company Critical Frequency. Welcome to Living on Earth Amy!

WESTERVELT: Thanks for having me. I'm excited to be here.

DOERING: Now, what were these two Guyanese citizens asking for in the lawsuit that they filed against Exxon in 2021?

WESTERVELT: Yeah, so this is a really interesting case. It is one of seven cases filed by one lawyer, who's a Guyanese woman named Melinda Janki. Went to law school, worked for BP as an in-house lawyer in the UK, and then eventually moved home to Guyana and started working on environmental law and is now kind of leading the legal charge trying to stop or at least slow down oil drilling in Guyana. So this case, she was representing two individual citizens who argued that the EPA in Guyana had sort of failed to do its due diligence in requiring certain type of insurance for this project. So they're supposed to have by the permit, they're supposed to have liability insurance from an independent insurance company and what's called an unlimited parent company guarantee. So basically, you know, if something happens, that is so catastrophically bad and so expensive to deal with that Exxon's local subsidiary which is called ESSO Exploration and Production Guyana Limited, which has, you know, maybe 1% of the assets that ExxonMobil has, then ExxonMobil will step in and sort of take care of the rest. So instead of having either of those things, they had an insurance policy that was from Exxon's own wholly owned subsidiary, an insurance firm in the UK and the parent company guarantee was only $2 billion. Which sounds like a lot of money but if you look at it in the context of, you know, say what the Deepwater Horizon spill cost to deal with, which was around $70 billion, you can see there's quite a bit of difference to make up there.

DOERING: Well, the judge, in this case, Sandil Kissoon, sided with the plaintiffs. What did he say about why?

Amy Westervelt and Kiana Wilburg, a reporter for Critical Frequency recording in the Kaieteur News studio in Georgetown, Guyana. (Photo: Courtesy of Amy Westervelt)

WESTERVELT: Yeah, he wrote a pretty blistering ruling. It's pretty short, it's around 50 pages, but it does not mince any words. He said that there was no reason that the EPA should not have required this guarantee that Exxon and the EPA had used secrecy and shadows to deceive the public. He required that all of this be fixed within the next 30 days, which is pretty quick to get, you know, a policy, this commitment in writing all of that. And he really sort of took the EPA to task for kind of, you know, doing the oil companies bidding rather than protecting the public. He also made a point of emphasizing that these two plaintiffs had standing to bring this case. So this was one of the arguments that the oil companies and the government had made was that, basically, they refer to these two citizens as mettlesome busy bodies and said that they should not have the right to bring a case requiring anything of the government or the oil companies. And the judge really struck that idea down and said that, you know, in fact, especially in the case of environmental issues, it's extremely important to protect the right of citizens to bring cases like this that are in the public interest. So that's a really big precedent.

DOERING: And do you know how important oil is to the Guyanese economy right now?

WESTERVELT: It's huge, but it's very interesting because on paper Guyana is the fastest growing economy on the planet, and their GDP is going up like crazy and there's a lot of talk about how everything is being driven by oil. However, there is not a lot of that that is really making its way to the people and there's a big concern that basically, by the time, oil starts to really pay off for the Guyanese people, there will have been a big oil spill or something that sort of negates that.

DOERING: Well how much pressure is the EPA of Guyana under to be able to cut through the red tape and move projects like this forward, despite the risks?

WESTERVELT: A lot of pressure. Whenever you kind of hear them talking, either the EPA officials or the vice president or the president of the country, they really seem to be worried that if they require too much of Exxon that it will mean, you know, that Exxon might leave or that Guyana won't end up making money off of the oil project. So in part, because of the way that the contract is structured between Exxon and Guyana, the government is sort of incentivized to try to move things along more quickly because the more barrels they produce, the more barrels they can sell, the faster they can sort of pay Exxon back for all of their expenses and get to a place where they are actually getting their kind of fifty-fifty revenue share that they're supposed to get. And then yeah, they're also concerned that if they place too many requirements on Exxon that, you know, either they might leave or other oil companies might not be interested. They are planning to auction off more offshore blocks and have said that they would like to get other oil companies operating there as well. So I think that's part of it too, that they want to remain kind of an attractive place for oil companies and part of how they do that is by minimizing red tape and oversight and regulations. And then on top of that 90% of Guyana's population lives on this very narrow sliver of coast and in addition to, you know, being potentially impacted by an oil spill, they are also looking at pretty intense sea level rise at the moment. So that stretch of coast in Guyana, is predicted to be underwater by 2030, not 2050, 2030!

DOERING: Less than in 10 years, oh my God.

WESTERVELT: Yes, so in this really, you know, kind of horrifying way, the government officials talk a lot about how they need this oil money to pay for climate adaptation.

DOERING: Well, I am curious, you know, what has Guyana said about its commitments to the Paris Climate Agreement and what sort of future is it looking towards?

According to an analysis performed by Guyana’s Bureau of Statistics in 2018, the tourism sector is the 2nd largest export sector for Guyana, injecting roughly $62.2 billion Guyanese dollars into the national economy. Eco-tourism is a major attraction in the country with activities like birdwatching and catch and release fishing. (Photo: Dan Sloan, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

WESTERVELT: Yeah, it's very interesting because they are still, you know, committed to the Paris accord and they are still a carbon sink and they have done some calculations and are claiming that even if they get, you know, five more of these production vessels going they will still be a carbon sink. Those calculations only take into account the emissions created by the sort of exploration and development of fossil fuel resources, they don't take scope three emissions into account, so the emissions created when people actually use the oil and gas, which makes it a little bit hard to take seriously. But you know, they make this argument that like, look, we have historically emitted, hardly anything, our people have very, very low emissions, very small footprints and we feel like we should be able to be in the oil business for a little bit to get some money for development. And if people are worried about climate change, then they should be focused on the big historical polluters and shutting down their oil and gas businesses. And they also kind of talk about it as something that they're doing as a short term thing, which is really interesting, like this idea that they can just be in the oil and gas business for 10, maybe 20 years, and then get out.

DOERING: Given that Guyana has these huge oil reserves and it is this light, sweet crude that gets a pretty high price, but also given the climate consequences of drilling and burning that oil, to what extent are they looking at other opportunities for growing their economy maybe with green energy or something else sustainable?

WESTERVELT: Yeah, not really at all, unfortunately. I mean there is an effort right now to commodify its carbon sink services. But it's just kind of such an absurd situation because in December of 2022, Guyana actually sold $750 million worth of carbon credits to Hess Corporation, which is one of Exxon's partners in the oil project to offset the emissions associated with the oil drilling. This is like a great example of where offsets go wrong I think because, you know, if you want to negate the impact of the oil and gas development there, the only real way to do that is to drill for less oil and gas. There is no universe in which, you know, paying for some of Guyana's forests, which were already going to be conserved, you know, those trees, where not going to be cut down anyway, that does not really cancel out the oil and gas development. This whole carbon credit thing came about because Guyana is actually the first participant in the UN's carbon trading scheme, which is called TREES. It's basically, you know, similar to its REDD+ scheme, where developed countries or high polluting countries pay less polluting countries to preserve trees or to sequester carbon. But as far as renewable energy, they're really not moving on that at all. There's a few small projects, but it just has not been a big area of investment in for them.

DOERING: Amy, what kind of impact do you think this ruling might have on other offshore oil drilling projects in Guyana and elsewhere?

WESTERVELT: I think it could potentially be really huge in either direction. You know, if the ruling holds, then I think that you could potentially see lawyers in multiple other countries that are dealing with similar situations, both in the Caribbean and also in Africa, kind of filing similar cases. If the ruling is overturned, the plaintiffs can still appeal to the Caribbean Court of Justice, which is sort of equivalent to the Supreme Court here in the US as the last step, and that could be an even bigger deal. This part of Latin America and the Caribbean is a big hot spot for oil majors right now. So I think the whole industry is going to be watching what happens with this case.

DOERING: Amy Westervelt is an investigative journalist and executive producer of the independent podcast production company Critical Frequency. Thank you so much, Amy.

WESTERVELT: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

DOERING: We reached out to ExxonMobil for comment but did not hear back in time for broadcast. In a published statement, they said in part “ExxonMobil Guyana and our co-venturers have adequate and appropriate insurance and proposed guarantees in an amount that exceeds industry precedents and an estimate of potential liability.”

Related links:

- Read the ruling by Guyana’s High Court Justice Sandil Kissoon

- Learn more about Amy Westervelt

- Reuters | “Exxon-Led Group Earned Nearly $6 Billion In Guyana Last Year”

- Bloomberg | “Exxon Breached Guyana Environmental Permit, High Court Rules”

- The Guardian | “Could Guyana’s Exxon Ruling Scare Big Oil Off Risky Exploration?”

[MUSIC: Kubix, “Deep Eyes” on Guitar Chant, Attik Production]

CURWOOD: Coming up – states that depend on the Colorado River for water finally come together in a bid to avert disaster. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Kubix, “Deep Eyes” on Guitar Chant, Attik Production]

Less Water for the Dry West

The Colorado River has been in a state of crisis due to warming weather and drought conditions. (Photo: G. Lamar, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

40 million people rely on the Colorado River for drinking water, irrigation, and energy. But a mega-drought linked to climate disruption has severely reduced the river’s flow over the past few decades, leading to a crisis in recent months with two key reservoirs at dire lows. But the summer of 2022, the federal government for the first time instructed the states that rely on the Colorado River to come up with a plan to cut water use. And after months of tense debates and delay, California, Arizona and Nevada have finally agreed to substantially reduce water use, at least for now. Here to tell us more is Luke Runyon, who covers the Colorado River Basin for station KUNC in Greeley, Colorado and hosts their podcast, "Thirst Gap: Learning to live with less on the Colorado River." Welcome back to Living on Earth, Luke!

RUNYON: Hey, thanks for having me.

DOERING: So just how big of a deal is this agreement?

RUNYON: It's hugely important because you have California, Arizona and Nevada, stepping up to the plate and saying that they're ready to commit to a certain amount of conservation, and particularly for California, because they haven't always been eager to sign on to conservation agreements in the past, because they kind of hold this more senior position on the river. But really, what's being proposed right now is another short term deal and this is an attempt to get the rivers negotiators, the policymakers to 2026, which is when a current set of managing guidelines for the river expire, and what the kind of community of people who negotiate on the river we're really needing was some stability in how the river functions, because we've been in crisis mode for the past several years. And no one was able to think long term, all of these crises were kind of sucking up all of the oxygen in the room and not allowing people to be thinking long term. And so the way that they're building this new proposal is this is what is going to get us through to 2026.

DOERING: Right, so what exactly have the states agreed to and how are they going to cut their water usage?

RUNYON: So the states are putting forward 3 million acre feet in cuts over the next three years and one acre foot for those people who aren't, you know, water nerds is about the amount of water that supplies two average households for their annual water use in the Southwest. So it's a lot of water and each state is going to kind of be approaching this in a different way. So let's start with California, California, a lot of the water that's used in California is used for agriculture, and it's used in these large irrigation districts. And each Irrigation District is going to kind of be approaching this differently. And what makes this deal different than past agreements is that this conservation is being incentivized by more than a billion dollars in federal funding from the Inflation Reduction Act. So this isn't necessarily, you know, these mandatory cutbacks and when slamming a hammer down really this conservation is being incentivized with this federal money. And each state is going to kind of be taking a different tack. You know, in in Nevada, really a lot of the Colorado River use is in the Las Vegas metro area. That city has been tremendously proactive in coming up with conservation agreements and programs, you know, lawn buyback programs, investing in water recycling. So they say that they're pretty well positioned to take these cutbacks that are being proposed.

DOERING: So there's this $1.2 billion coming from the federal government to help ease some of this pain. To what extent do you think that is enough to soften the blow partially or even fully?

Reporter Luke Runyon covers the Colorado River basin for KUNC and 20+ NPR stations in the southwest. He also hosts KUNC’s podcast, “Thirst Gap: Learning to live with less on the Colorado River.” (Photo: Courtesy of Luke Runyon)

RUNYON: Well, I don't want to shake a stick at a billion dollars, because it sounds like an awful lot of money but, you know, I think we know that adapting to climate change is going to be a very costly process not just for the American Southwest when it comes to adapting to water scarcity but whether you're looking at rising seas along the coast or increasing natural disasters, I mean, these are events, these are trends that are going to be extremely costly to learn to live with. Whether that's coming in the form of paying farmers not to farm or making huge upgrades to water infrastructure. I mean, these projects add up really quickly and you can spend a billion dollars pretty easily in just a matter of a few months. So I think it's going to take a lot more money in order to try and make the region more resilient to climate change.

DOERING: Now, this is a proposal that Arizona, California and Nevada have all agreed to, when should we expect to start seeing these water cuts and how soon after that might we see results in the Colorado River itself?

RUNYON: Well, some of the states say that they're ready to start implementing this agreement right away, even though it still has to go through a federal review, there's still several hoops that this proposal would have to jump through before it's finalized. At least some of the people who negotiated say that they're not waiting, they know that the Colorado River needs this kind of conservation now, and they're ready to start implementing some of these cuts already. So I spoke with the chief negotiator on river issues for the state of California and he said, you know, now that we have this proposal in place, we're going to start pursuing some of these contracts with irrigation districts, that sort of thing in order to start implementing this right away. And, you know, there's the potential that that could start showing up in the Colorado rivers largest Reservoir, Lake Mead almost immediately, you know, if you stop taking water out, it stays in the reservoir and that has an immediate effect. But like I said, we still don’t know a lot of the details of exactly how much water when over the course of these three years, this is going to be taking place, how quickly this money is going to be going out. So we'll still kind of have to be watching over the next several months, several years to know exactly how this proposal is implemented.

DOERING: Now, I know that the American West had actually a very wet winter this year, we heard about these atmospheric rivers hitting California. To what extent did that factor into these discussions at all?

RUNYON: The wet winter was hugely important. We would as a region be having a very different conversation, if the Southwest had had just a slightly dry winter but we had a tremendous amount of snow in the Rocky Mountains and the Colorado River is snow fed and that factored into these negotiations in that they allowed some of the pressure to be eased on the people who were negotiating. I mean, the cuts that we were talking about last summer were huge. This is not that agreement, the cutbacks that are being proposed now are significantly less than what were put forward by federal officials last year saying this is what's necessary to save the Colorado River. This agreement is not that. And that's because everyone got this reprieve from mother nature in the form of a really wet winter.

Pictured is the White River National Forest in Colorado. Snowfall over the last year helped replenish the Colorado River’s water supply. (Photo: Sathish J, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Luke, what do you see as the next steps in the process of protecting this watershed?

RUNYON: Now that this proposal is on its way too, being finalized. All of the discussion is going to be on these post 2026 managing guidelines for the river. And a lot of the hard conversations, hard discussions, a lot of the big swirling unanswered questions on the river everyone has been putting those off until this moment, because all of the focus of the conversation has been on managing this crisis, managing the emergency. And hopefully with this agreement coming together now, those policymakers can actually sit down and talk about what the future of this watershed really looks like. Hopefully, it won't be in such an emergency mode and you can talk about how you go about answering all these big questions about how do you go about reducing demand. How do you better include stakeholders in the process of managing this river? Whether that's tribal nations, whether that's the country of Mexico, whether that's the environmental community recreation groups. How do you go about creating a more inclusive process to manage this river? Those are conversations that are going to be had now because this new proposal has come together.

DOERING: Luke Runyon is a reporter with KUNC in Greeley Colorado, who covers the Colorado River Basin. Luke, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

RUNYON: Yeah, thanks for having me.

Related links:

- The Washington Post | “States Reach Deal with Biden To Protect Drought-Stricken Colorado River”

- Luke Runyon’s podcast with KUNC, “Thirst Gap: Learning to live with less on the Colorado River”

[MUSIC: Nathaniel Rateliff, “And It's Still Alright” on And It’s Still Alright, Stax Records]

The Great Displacement

“The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration” is the new book by Jake Bittle. (Photo: Courtesy of Simon and Schuster)

CURWOOD: Climate change is bringing more than just painful discussions about water use. It’s already making some places across the country unlivable and seems likely to uproot millions of Americans in the coming decades. That’s the focus of journalist Jake Bittle’s new book, “The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration.” He collected the stories of people across the US who have been driven out by floods, fires, droughts, and extreme heat. Jake Bittle joined the Living on Earth Book Club at a live event at UMass Boston to share his insights on this radical reshaping of American geography. I asked him how his project began.

BITTLE: So before I wrote about climate change, I mostly wrote about housing, and I had learned about a federal government program in Houston, where the government paid people to leave their homes, and they knocked down homes that were perennially flooding. You know, they'd flood ten, twelve times, in as many years. And I went to Houston to write a magazine article about it, and I walked around these neighborhoods that had been completely emptied out, you know, in the middle of a relatively dense city. And I was mostly writing about the people who had hung on and, you know, not participated in the program, and were staying in these empty areas. But during the course of writing that article, I sort of started to wonder, 'Where did all the people who took the money end up?' And almost nobody could tell me. FEMA couldn't tell me, Houston couldn't tell me, the neighbors couldn't tell me, maybe there was one academic who had tried to find it out. And that was the seed for the book was I used the federal database of buyouts and then I used the white pages to find all the people who had lived in these homes before. And I ended up with maybe ten, or twelve times as much material as I was able to use in the article and it quickly became clear to me that it wasn't a problem that was localized to Houston, it wasn't a phenomenon that was specific to flooding. It was a sort of very unremarked upon or poorly understood movement that was going on after these disasters all over the country. And that was kind of the initial idea for the project.

CURWOOD: What did the people who stayed think? It's like more than a thousand bucks a month to pay for insurance for the place which probably the mortgage payment itself...

BITTLE: It's much less than that.

Jake Bittle is the author of “The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration”. (Photo: Jasmine Clarke)

CURWOOD: Could be less than that in many of these places.

BITTLE: Yeah.

CURWOOD: If they saw this devastation, why did they stay?

BITTLE: Yeah, it's a really, really good question. It's always a very messy topic, you know, movement decisions and migration, people don't really act, always, in the ways that we expect them to. It seems to be different for each person, but I think there were sort of two reasons. One was that people really have a really, really strong attachment to the place that they're from, and in a lot of cases, there just isn't another part of the country, or indeed, the world that is similar, and everyone they know lives there, that's where they work. You know, they had had insurance so they were able to rebuild after a flood. And they just thought, 'Well, you know, I don't want to leave, there's not really anywhere else I can go that's as affordable as this neighborhood.' The other side of it, though, is that it's really hard to find somebody to buy your house if you want to sell it. So there's a separate piece where the homes become albatrosses. What you'll see is a lot of people who are stuck, you know, they basically have no option but to sort of plead at a political level for what in the book, you know, I think I describe fairly as a bailout, it's not their fault for living there, but the only solution, realistically, is for the government, you know, which doesn't have a stake in it, to pump money in to get people out of their homes. And the government, I think, has to act as a backstop in the same way that the Federal Reserve does for banks. You know, FEMA, or whichever branch you prefer, can act as a backstop for the housing market and just say, 'Look, the only realistic solution is for the government to intervene because the market has just completely broken down.' So yeah, you have then people who are in love, or they're trapped, you know, and sometimes they're both.

Climate change is causing more frequent flooding events (Photo: Staff Sgt. Daniel J. Martinez, Air National Guard, Picryl, public domain)

CURWOOD: Yeah, talk to me about insurance in a place like Norfolk, Virginia, say.

BITTLE: Yeah, so most people there for flood insurance, they purchase a policy from a federal government program because most private companies don't offer it because it's not profitable. But those policies are getting extraordinarily expensive. I'd spoke to several families who are paying upwards of $13,000 a year for policies, that's more than 300 times what it was a couple of years ago. And there's not really a cap on that. And I think it's interesting, because what the policy, what that number is trying to communicate is that, you know, one day the home will be potentially permanently underwater. So its value is essentially nil. And the cost of protecting it is infinity. So that number, which is impossible for families to pay, is sort of communicating, like, the financial system of homeownership can't sustain you living here. But for the people in that position, it just feels like a massive, you know, financial burden and often leads to them having to, to leave.

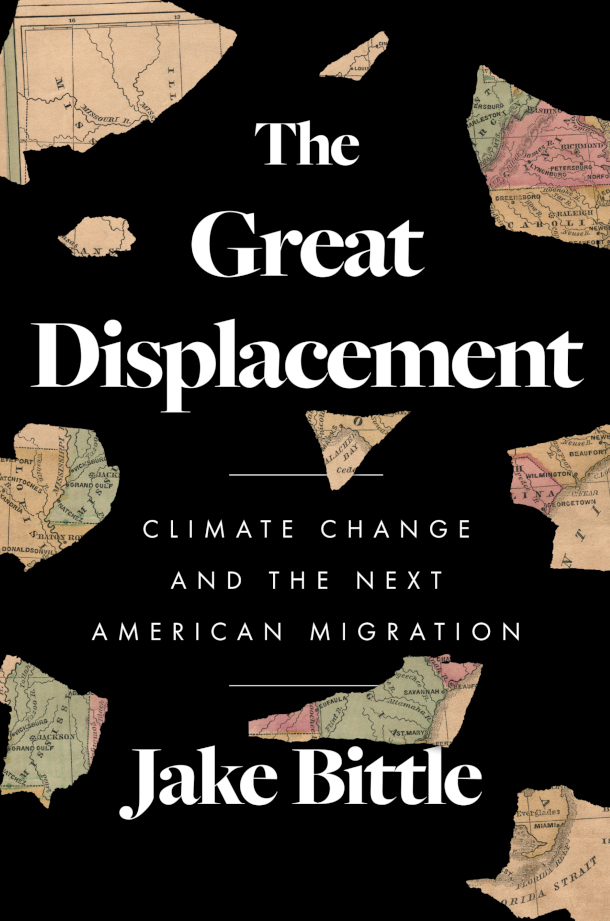

CURWOOD: You know, you reveal in your book that the major cause of truly regional migration isn't necessarily that sudden weather event, the flood, or the hurricane, the fire, but the gradual increase in temperature. Why is that?

BITTLE: I think that it's because of the way that people experience risk, right? I think that, you know, the chances that my town is gonna get hit by a hurricane each year, they're always going to be relatively low, it's never going to be 100%, right? And you can always kind of say, 'Okay, well, you know, maybe this flood insurance payment is too high in this home, but what if I move to higher ground, you know, just a couple miles away,' right? 'And get a discount on my premium.' But I think the idea that every summer, you're going to face lethal temperatures, right? There's health impacts, it's extremely dangerous to raise children in that kind of weather. I think that is what's going to make people make this psychological decision to make an elective movement away from these areas and away from the regions as a whole, right? Because of the way that we've built our cities and, you know, because of the way we've built against rivers and mountains, there's always a place that's more resilient to flooding or fire than, you know, a place 10 miles away. But heat is a, you know, it's an atmospheric phenomenon, it's not something you can avoid, just by moving a couple miles away, you have to move to a place that's more temperate, and even then you're not totally out of danger. So I think that that's the kind of thing is, it's not really a financial burden, people won't experience it financially. It's not even necessarily, you know, like something that's going to damage their property. It's just the feeling of 'Okay, as long as I live here, I'm going to have to deal with this.' That's going to change a lot of people's minds, I think, especially when you look into the health impacts on older people and very young people.

Sea-level rise is causing storm surge to flood coastal infrastructure more, leading to more damage and higher insurance premiums (Photo: pxfuel)

CURWOOD: And what about businesses? I mean, business and industry is going to have to migrate.

BITTLE: Right, certainly. I mean, look at, you know, San Francisco, for instance, a lot of tech companies have said, you know, 'Our workers don't want to come to work, they don't want to live here, because they're concerned about crime, they're concerned about quality of life,' and it turned into a hair-pulling moment for the industry. It's not that hard to imagine all the tech companies, for instance, that are being headquartered in Austin, right now, a lot of them have moved to Miami, it's not that hard to imagine them saying, 'Uh-oh, our workers don't want to live here, because it's far too hot. We have to make sure that we move our offices somewhere else so that we can attract talent.' You know, it's not happening yet. But it's it's far from implausible.

CURWOOD: So, the subtitle of your book includes migration, 'the Next American Migration.' Where are people going? If they figure out they have to leave?

Global warming will cause regional migration as some areas begin to see lethal temperatures every summer (Photo: Rebecca Lindsey, Climate.gov)

BITTLE: Yeah, if you look at a map, and you sort of assess on paper, what are the places but the least vulnerability to hurricanes, storm surge, sea-level rise, wildfires, drought, etc, you end up with a list of cities, mostly in the Upper Midwest, right? Cincinnati is often put forward as a potential place because it could house twice the number of people that it currently does, it has an abundant supply of fresh water. Buffalo for all its many weather issues is often said to be like one of the most resilient places to climate change. I think that, you know, the fate of coastal cities like Boston, whether they become moving sites for people really depends a lot on how much we spend on ensuring that they're resilient to the biggest disasters, right? So there's a version of Boston, where there's a giant green ring around the waterfront and it's really, really difficult to imagine a storm big enough to flood the city. You know, that's definitely possible. But it's sort of up in the air, I think. But there are places that are sort of ready-made for this right? Duluth, Minnesota, Chicago to a certain extent, that those may be the places where, if you were making a hypothetical decision about where to put your money, you might end up there, right? But that doesn't imply that people will make such rational decisions. It's just like, on paper, they look good right? You know? I think what's important to emphasize is it doesn't necessarily need to involve people from the South picking up their things and moving north. In the short term, they mostly go, I think, the shortest possible distance that they can, right? A lot of times they end up moving into another place that's just as vulnerable, or they move to the closest city where they can find cheap housing, right? So, sometimes they'll move from a rural area to a nearby city, you know, anything to maintain the social ties that they already have. You're not seeing a, you know, a march north or a movement west on the scale of the Dust Bowl, but you are seeing people start to say, 'Okay, well, there's certain areas, often rural areas that are extremely high risk and don't have enough money to keep up with the pace of disaster.' And then so the locus of investment and growth will gradually shift to the north I think. But it can take a while and I think the rest of the country has to look even worse than it does now. And that may not change for, you know, a few decades until you start to see some really devastating and chronic events.

CURWOOD: That’s Jake Bittle, author of The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration. You can watch the full video of our live event with Jake Bittle at loe.org/events.

Related links:

- Jake Bittle’s Website

- Find the book “The Great Displacement” here (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Watch the full live event recording here

[MUSIC: Nathaniel Rateliff, “What A Drag” on And It’s Still Alright, Stax Records]

DOERING: Coming up – Bisphenol A, known as BPA, in sports bras and yoga pants may be hazardous for our health. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Martin Klem, “Coyote Wedding” on Coyote Sundance, Epidemic Sound]

Beyond the Headlines

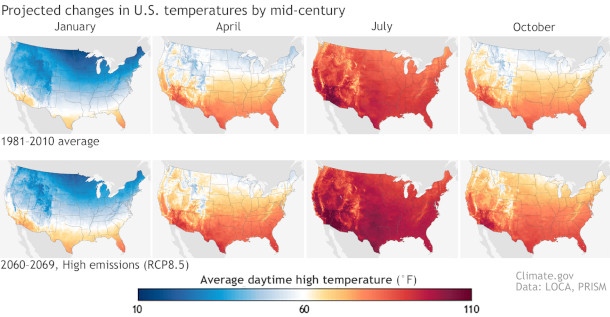

Montana Governor Greg Gianforte (center) has signed a bill considered by many critics to be one of the worst anti-climate laws in the country. (Photo: USDA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. On the line with me now from Atlanta, Georgia is Living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra. Hey there Peter, what you got?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. You know, we look all the time in the news at some of that screwy stuff that goes on in Washington DC, with Congress and with federal laws, but if you ever want a break from what's screwy in Washington, sometimes look at screwy state legislatures. Up in Montana, legislators in a Republican-dominated body have passed a law that bars state agencies from considering climate change when issuing permits for large projects. It's almost the equivalent of Florida's "Don't Say Gay" law for the climate.

CURWOOD: Wait, what you're telling me is that in Montana, now, they've enacted this law that says, oh, if you're gonna be building out any coal or oil or gas infrastructure, you cannot calculate any impact on climate disruption?

DYKSTRA: That’s pretty much it and Montana has bought in pretty big on the fossil fuel side of the agenda. The eastern part of the state includes a big part of the Bakken Formation that dominates the economy and environment in North Dakota. It's one of the largest oil and gas fields in the United States. And much of Montana-bordering Wyoming also includes major coal fields as well. When Governor Greg Gianforte signed the bill, he furthered a climate, no pun intended, of denial. If you don't mention climate change, it's all going to go away simply by banging the gavel and signing it with Governor Gianforte's signature.

CURWOOD: All right, Peter, what else is going on?

A nonprofit called the Center for Environmental Health has warned manufacturers of athletic clothing like sports bras, leggings, and shirts that their products have been shown to contain BPA. (Photo: Clique Images, Unsplash)

DYKSTRA: A nonprofit group called the Center for Environmental Health, sent notices to some of the biggest manufacturers of leggings, sports, bras, shorts, athletic shirts. It says that growing numbers of athletic clothing have high levels of BPA, considered to be a fairly dangerous group of chemicals. Their testing showed that the clothing could expose wearers to up to 40 times the safe limit of BPA, based on California's tight standards. BPA has been linked to everything from obesity, to cancer, to diabetes, to heart problems.

CURWOOD: Now that's not a government agency. What exactly did they do?

DYKSTRA: They haven't issued a new report per se. But based on their testing, they wanted to let these companies know that they could be in legal jeopardy if the BPA levels in these sporting apparel products is as dangerous as it appeared to be when they took their tests. BPA came into popularity as a plastic softener. And that's how it got used in things like baby bottles. It was outlawed in things like plastic bottles for kids. Now, here's another level of concern.

CURWOOD: Yeah. And how ironic is this that somebody wearing workout gear presumably to get in better shape could be wearing a garment that actually could make them fatter or make them sick?

DYKSTRA: Oh, wanting to improve your health could be hazardous to your health?

CURWOOD: I wish it were funny, but it isn't, is it? Hey, what do you have from the annals of history for us today?

DYKSTRA: 125 years ago, May 29, 1898, a dispute over the will of the late Alfred Nobel is settled by his family members. Nobel invented dynamite and he made a fortune and wanted to leave that fortune, in part, presumably out of guilt for inventing dynamite to the creation of prizes that would celebrate the betterment of humankind. And to this day, we mark not only the Peace Prize, but other Prizes in economics, literature, chemistry, physics, medicine, and they're still pretty pricey prizes and certainly prestigious ones.

Alfred Nobel dedicated much of his fortune to establishing the Nobel Prizes. (Photo: Gösta Florman, The Royal Library of Sweden, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: And a number of interesting folks have won these over the years. Peter.

DYKSTRA: That’s right, former Vice President Al Gore being one of them. He shared the prize with the scientists of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. There are others like the chemists who discovered the ozone hole over the South Pole and the North Pole, and others throughout the years that have advocated both on the political and the scientific end to better protect our climate.

CURWOOD: Well, I'm thinking of Wangari Maathai, of course from East Africa, who you know, showed us the way towards protecting the planet by protecting our trees. Hey, Peter Dykstra is a contributor to Living on Earth. We'll talk to you again real soon, Peter.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve. Thanks a lot and we'll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth webpage. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “Montana’s New Anti-Climate Law May Be the Most Aggressive in the Nation”

- Center for Environmental Health | “New Testing Shows High Levels of BPA in Sports Bras and Athletic Shirts”

- Learn more about the history of Alfred Nobel’s will

[MUSIC: Sunburst, “Let’s Live Together” on Ave Africa: The Complete Recordings 1973-1976]

Note on Emerging Science: How Lizards Can Breathe Underwater

Anoles can pull off impressive feats of underwater breathing. The secret, researchers found, is the lizard’s ability to “rebreathe” using a bubble that forms around its snout. (Photo: Adrien Chateignier, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: In a moment, zombie worms and other unusual life forms that emerge when a whale dies, but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

LYMAN: Anoles – small tropical lizards found mainly in Central and South America, and the Caribbean – will sometimes dive underwater when threatened. Some anoles can stay underwater for up to 20 minutes, but until recently it wasn’t known how they managed to stay submerged for so long. In an effort to find out, Chris Boccia, a doctoral student at Queen’s University in Kingston, Canada, and his colleagues, traveled to Costa Rica where they captured 300 anoles of various species. Some of the experimental anoles were found near streams, while others were found away from streams. Boccia and his fellow researchers then dunked each lizard into containers of river water. While they were underwater, all of the anoles had a bubble of air around their snouts, and they appeared to breathe the bubble in and out. The lizards that were found near streams rebreathed the bubble more often and stayed submerged longer than their land-based relatives, Boccia and his colleagues reported in the Journal of Current Biology. Boccia said that one lizard was underwater for 18 minutes.

Scientists are still figuring out how anoles can rely on their snout bubbles for so long without running out of oxygen. (Photo: Adrien Chateignier, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

By inserting a small oxygen sensor into the bubbles around the submerged lizards’ snouts, the researchers confirmed that the oxygen levels in the bubbles slowly decreased as the lizards breathed. Boccia suspects the anoles may be able to stay submerged for several minutes by slowing down their metabolism, thus reducing the need for oxygen. He also speculates that as oxygen levels in the snout bubble drop and carbon dioxide levels rise, the bubble may obtain more oxygen by releasing CO2 and taking up dissolved oxygen from the water, but more research is needed to confirm that hypothesis. That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

Related links:

- Read the full study

- Get a close-up look at anoles’ snout bubbles

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

The Life of a Dead Whale Fall

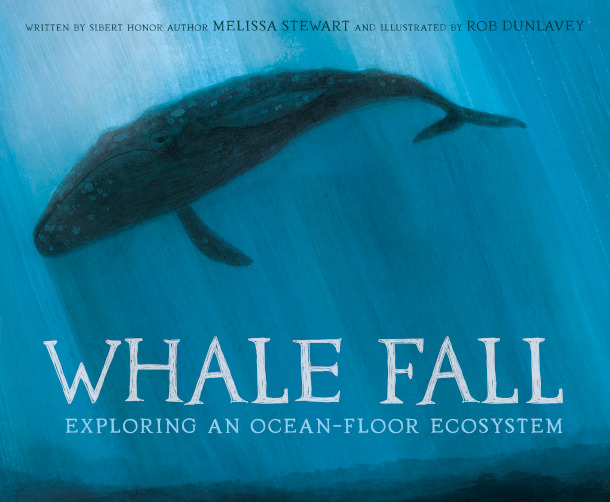

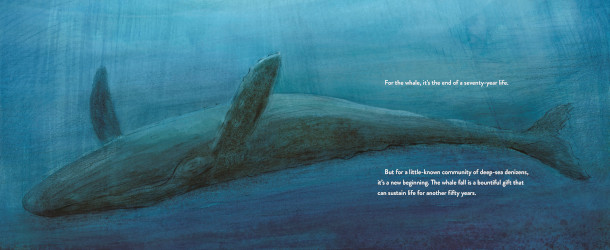

“Whale Fall: Exploring an Ocean-Floor Ecosystem” is the new book written by Melissa Stewart and illustrated by Rob Dunlavey. (Photo: Courtesy of Random House)

CURWOOD: When a whale dies, it eventually sinks to the ocean floor. And although that whale’s life is over, that’s when a whole new circle of life kicks off. For fifty or more years, the whale’s meat, blubber, and bones feed thousands of other organisms including hagfish, zombie worms, octopuses and more. Scientists only started documenting these ocean-floor ecosystems, called “Whale Falls,” in the last few decades. The ocean is a huge place, and it can be harder to send a person to its deepest parts than into outer space. But when children’s author Melissa Stewart heard about these unique ecosystems she decided to write a book. Her 2023 volume is called “Whale Fall: Exploring an Ocean-Floor Ecosystem,” and Melissa Stewart joins me now to discuss. Welcome to Living on Earth!

STEWART: It's great to be here. Thanks for having me.

DOERING: So a whale fall starts with a death. But then it goes on to nourish a whole ecosystem of deep sea life. Can you tell us about sort of the process that happens over 50 years?

Melissa Stewart is the author of “Whale Fall: Exploring an Ocean-Floor Ecosystem,” as well as over 200 other books for children. (Photo: Courtesy of Melissa Stewart)

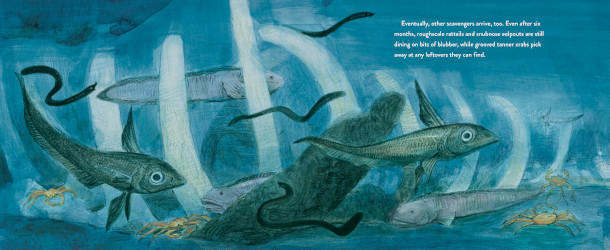

STEWART: Yeah, so a whale, like let's say a gray whale, can live for 70 years, but then when it falls to the ocean floor, it can fuel this community for another 50 or so years, and there are distinct phases of the decomposition process of the whale. So it will start out by attracting sleeper sharks, and also hagfish. They can smell the whale from miles around as it's laying there in the very early stages of the decomposition. And so they will do some of the initial feeding. And so you go through phases of different communities of creatures. And so there are crabs that come in, there are different kinds of fish that come in. And then there are also creatures that feed on the animals that are feeding on the whale fall. So for example, there can be just billions of little creatures called amphipods, which are sort of like shrimp. But then there are octopuses that come in and feed on those ampiphods, for example, but then as there gets to be less and less blubber less and less meat that are actually on the bones, then there are animals that come in and actually start to feed on the bones themselves. And so initially, animals like zombie worms, they release a substance that kind of will ooze into the bones. And they can get in and get nourishment out the bones, but they can only reach so far. And then there are even more creatures that will come in. So eventually, we get down to a stage where there's bacteria, and it will become a chemosynthetic ecosystem. And these deep sea microbes that are feeding on the whale fall will actually be housed inside of other creatures like clams and tubeworms that provide a home for these creatures, but also they are feeding on those little microbes themselves.

DOERING: So at first glance, this seems like kind of a morbid topic for a children's book. How did you come to choose a whale fall as the topic for your latest children's book?

The illustrations in Whale Fall help to teach children about this extraordinary ecosystem (Photo: Courtesy of Random House)

STEWART: The story behind this book traces back to an earlier book that I wrote, which is called, Ick: Delightfully Disgusting Animal Dinners, Dwellings and Defenses. And when I was researching that book, I was looking for animals that lived in really interesting environments that were somehow gross, unusual or disgusting. And so I came across zombie worms, which are also known as bone eating snot flower worms. So right there, you gotta have to just fall in love with that name, right? And I was so interested in the way that they live, they have such an unusual lifestyle. And one of the most interesting things about them is that the females are about one or two inches tall. They live on the bones of the whales as they're decaying. But the males are microscopic, and they live inside the female bodies.

DOERING: Wow. I've never even heard of creatures that live like that.

Thousands of different species are nourished by a whale fall such as roughscale rattails, snubnose eelpouts and tanner crabs. (Photo: Courtesy of Random House)

STEWART: Pretty amazing. And so as I was researching that book, and gathering all the information, I knew that I could only write about 400 words on zombie worms. And I had a lot more to say, not only about them, but also about this incredible environment that they live in. That was my access point into whale falls, and all the different creatures that live there. Thousands of different species can live at a whale fall during its 50 year life while the whale is decaying. And they have some of the most incredible names that you can imagine things like, rough scale rat tail and blob sculpin. And one of my favorites is sea pigs, which is a little sea cucumber, but it looks a lot like a pig. It's bright pink, and it has little feet like a pig. They're just, they're delightful little creatures. And I really wanted to write a book that focused on that ecosystem.

DOERING: Well, what inspired you to become a children's author and share stories about the environment with kids?

Even when only the bones remain, the whale fall continues to feed strange organisms that are able to break down the bones like zombie worms and their symbiotic bacteria (Photo: Courtesy of Random House)

STEWART: I think it really traces back to my family, to my parents, the way I was raised. When we were young, both my brother and I used to go out exploring and on walks. There was a national forest across the street from our house. So we had a lot of free rein to explore and discover. But when we went on these walks with my dad, he would always be asking us questions, to help nurture our curiosity about the natural world and what we were seeing around us. And I can remember one day, he took us to an area of the woods that we had never been to before. And he said, do you notice anything strange about the trees in this area? I noticed that all the trees seemed kind of small. And he said, great observation. The reason for that is because about 25 years ago, there was a fire in this forest. And all the trees burned down, many of the creatures had to run away and live in other parts of the wood. But over time, things have started to grow back and animals have returned. And that was a really powerful moment to me, because I was about eight years old. And it taught me two things. First of all, that the natural world is so powerful, that it can rejuvenate itself, that it can endure all kinds of calamities and rebound. But number two, it taught me that if you look around, you can read the history of a natural area through your observations. And that really hooked me. That was what made me want to become a scientist, and kind of launched me on a journey to discover as much as I can about the natural world and share it with other people.

DOERING: Melissa Stewart is the author of Whale Fall, as well as over 200 other science books for children. Melissa, thank you so much for joining us.

STEWART: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- NOAA | “What is a Whale Fall?”

- Melissa Stewart’s Website

- Find the book “Whale Fall” (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Paul Winter Consort, “Lullaby From the Great Mother Whale to the Baby Seal Pups” on Concert For the Earth, by Paul Winter, Living Music]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Swayam Gagneja, Madison Goldberg, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Jusneel Mahal, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Clare Shanahan, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari. We bid Iris Chen and Louis Mallison a fond farewell this week. Thank you both for all your hard work!

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth