Black Courage Upon the Sea: Robert Smalls' Heroic Escape From Slavery

Air Date: Week of June 16, 2023

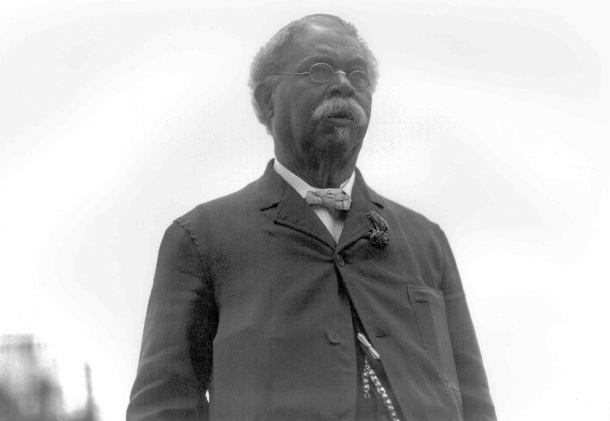

After freeing himself and his family from slavery in a daring maritime escape, Robert Smalls enlisted as a ship pilot with the Union. Following the Civil War, he returned to South Carolina and embarked on a political career. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael B. Moore)

One night in May of 1862, an intrepid Black man named Robert Smalls commandeered a Confederate ship called The Planter in Charleston, South Carolina and liberated himself and his family from enslavement. His great-great grandson Michael B. Moore and retired four-star Admiral Cecil Haney join Host Steve Curwood to share and reflect on the harrowing story of his escape and life of public service after gaining his freedom.

Transcript

CURWOOD: If hope sometimes feels impossible in the face of climate disaster, imagine how remote hope for a better future would have seemed for the African Americans enslaved in this country over more than 200 years. And yet, some did dare to dream of a free life for themselves and their families, and a few even risked everything to escape. Their courage serves as a reminder that even in the most adverse of circumstances, a way forward is possible. As we continue our celebration of Juneteenth and emancipation, we turn now to an astonishing story of courage when a brave black man named Robert Smalls and his friends commandeered a confederate ship and steered themselves and their families to freedom one night in May of 1862. His great-great grandson Michael B. Moore, a business leader and author, joined two other special guests for our live Juneteenth event in 2022. Admiral Cecil D. Haney, now retired, was the second Black four-star admiral in US Navy history and served as Commander of the United States Strategic Command for three years, in addition to commanding the US Pacific Fleet before that. And Joel Christian Gill is a cartoonist, historian, and author of a graphic biography of Robert Smalls. Robert was born into slavery in 1839 to a mother who served the white masters of a house in seaside Beaufort, South Carolina. He grew up with more autonomy than many of his peers and had a streak of independence that sometimes got him into trouble. As a young teen, Robert Smalls was caught in the streets after the curfew at night fall for Black people and arrested. But he was able to talk his way out of a whipping and got off with just a stern warning, though his master later sent him off to be hired in Charleston where he was allowed to keep a small amount of his wages. Robert Smalls was ethnically Gullah Geechee, a society of African descendants along the coast and sea islands of the Carolinas, Georgia, and North Florida. And his familiarity with the sea would become his key to freedom via a ship called The Planter. His great-great grandson Michael B. Moore shares the amazing story of how Robert Smalls took his fate into his own hands.

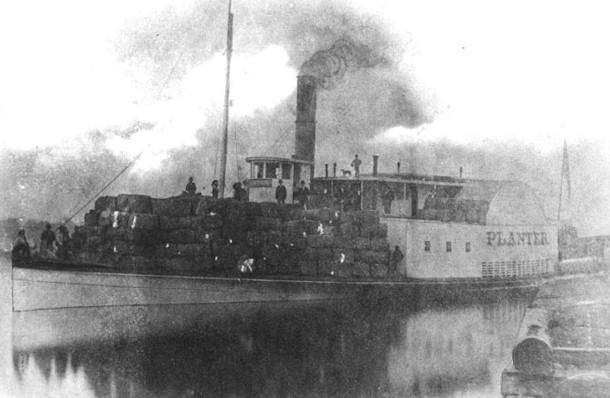

While enslaved, Smalls piloted a steamship called the Planter . In an incredible feat, he took control of the ship and steered himself and his family, as well as his fellow crewmembers and their families, to freedom. (Photo: Naval History and Heritage Command, Public Domain)

MOORE: Yeah, he was working on the Planter. And you know, as fate would have it, the Planter, because of its value, was taken over by the Confederate Army once the Civil War began. And he was its pilot, he moved up the ranks and ended up being the pilot, as I understand it back then. Clearly he was not the captain of that ship, but he was the person who was sailing the ship, maneuvering the ship, here and there. And so he knew how to sail the ship. He knew the ins and outs of the waterways of the low country. And personally, he was in his low 20s: 23, 24. He was married, he had two young children. And he was just a father, a husband, he loved his family. And he knew that just the reality of slavery was that his family, his wife, his children could be sold away from him in an instant. And so he thought, you know, very deeply about how to do something about that. One of the things that he did, you know, Robert, as mentioned, he was hired out, he got a salary that he sent back to his master in Beaufort, but he was able to keep a dollar a week. And with that dollar, he bought various sundries, tobacco, candies, fruit that he then sold on the docks. And he saved every penny and ended up negotiating for the life of his wife and children with his wife's master. He put down a hundred-dollar down payment on the life of his family with a total sort of purchase price of about $500. But that was precarious. He knew how long it took him to earn that much money to save up that much money. And so he knew that there was a United States blockade, a federal blockade just outside the mouth of the harbor. And he knew that if he could somehow figure out a way to get there, that he'd be free.

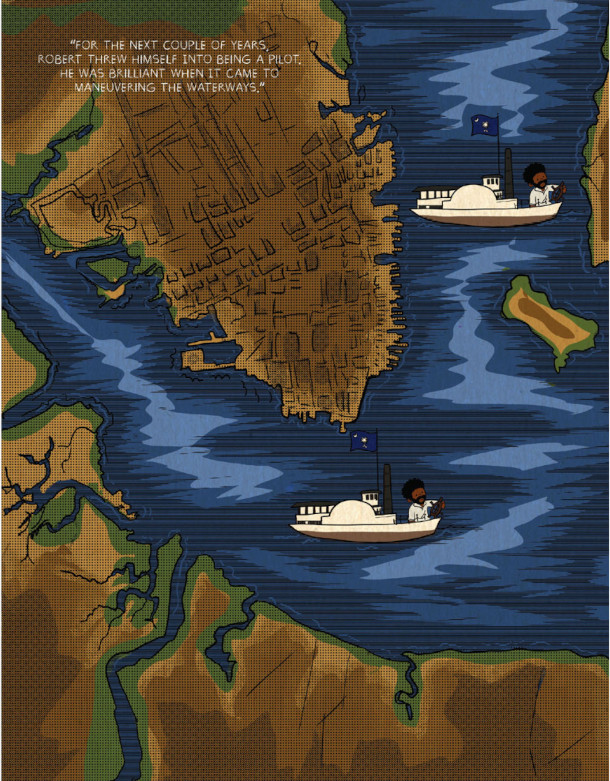

Smalls had become an expert at navigating complicated waters during his time as pilot of the Planter. Above, a page from the graphic biography Tales of the Talented Tenth No. 3: Robert Smalls, by Joel Christian Gill. (Photo: Courtesy of Joel Christian Gill)

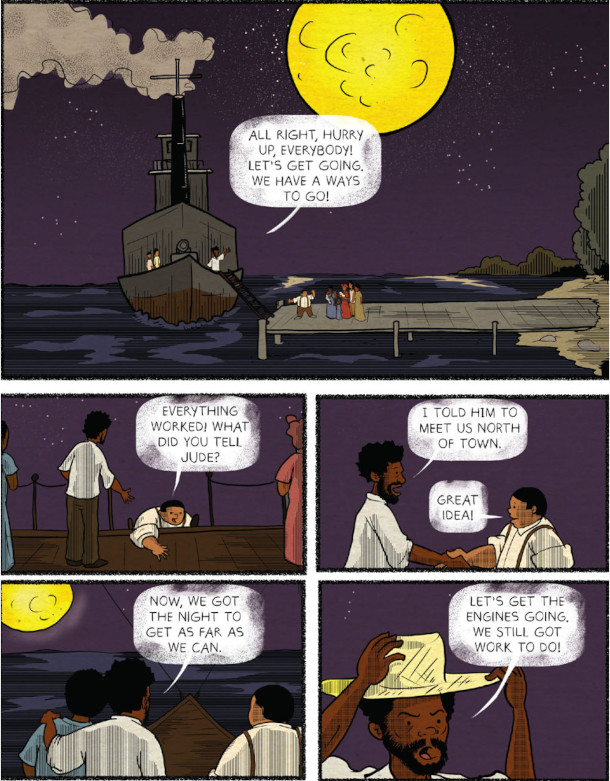

And so he noticed that the Confederate crew from time to time would leave for the night. They weren't supposed to, but they would leave for the night, not to come back until the next day. And he concocted a plan. He got together the other enslaved crew of the Planter, and came up with a plan that one night, it ended up being the night of May 12, 1862 into the morning, the early morning hours of May 13. The Confederate crew left, he got his family, the enslaved crew and their families. He famously sort of donned the top hat and this long overcoat of the Confederate captain of the Planter and got up into the wheelhouse and he was able to sort of mock, as the story goes, the Confederate captain had a, you know, an unusual noteworthy kind of gait, about him. And at distance, and in the middle of the night, Robert was able to mock that, mimic that. Because he was the pilot of the boat, he knew the pass codes to get past the four or five forts in Charleston Harbor. And he essentially bet everything he had on everything he dreamed of and won. They lined the bottom of the boat with dynamite, they knew that if they had gotten caught, that they would be executed probably in a particularly gruesome way as an example, you know, for others who might have that kind of an idea. And so it was a life or death proposition. I often think, you know, it is so complicated, I imagine, in the dead of night to sail a boat through, you know, a busy and complicated harbor. But to do that, under the threat of, of death, if something were to go wrong, you know, it's an amazing challenge. And I often think you know, that if something had gone wrong, I mean, clearly, I would not be here. So, I have lots to thank Robert Smalls about, but certainly his bravery and his skill are among the top.

CURWOOD: So, what happened to Robert Smalls after he got his family to freedom? I imagine the union folks on the boat were pretty surprised to see this confederate ship sailing towards them, but I gather they didn't fire, huh?

Preparing for the night’s journey through the harbor, from Tales of the Talented Tenth . (Photo: Courtesy of Joel Christian Gill)

MOORE: Yeah, as the stories go, Robert had thought through all the details. He had thought through, you know, all of the intricacies of getting to freedom to that blockade, except for one detail, which was here is this they say one of the largest boats in the harbor, you know, steaming full steam ahead toward this huge blockade with an enormous confederate flag. And so he had forgotten that detail. So very quickly, they lower the Confederate flag. My great great grandmother, Hannah had thought about that detail, though, thankfully, and had sewn together a number of bedsheets into the universal white flag of surrender. And that saved them because they also, they could have gotten past all of the Confederate forts but then also, you know, run into trouble with the union blockade and gotten killed by them. So yeah, it was a precarious, audacious kind of a plan and, you know, God was with them. You know, Robert got a reward for delivering the Planter to the United States. He didn't actually get sort of the equation of what Congress sort of prescribed for these matters, I think they couldn't see fit to give a black man that much money, but he got a handsome reward. And he was received up and down the east coast as a hero, one of the first real heroes of the Civil War. And he could have lived a very comfortable, happy life as a civil war hero. But instead, he decided to go back into the crucible of the war effort, he freed himself, he freed his family, but he also wanted to free others like him who were enslaved and came back and fought actually on the Planter. Again, as the story goes, he became the first African American to command a United States Naval Vessel, became a captain of the Planter, fought in 18 battles, was taken by Admiral S.F. Du Pont to Washington to meet with President Lincoln and Secretary of War Stanton. And as the story goes, by virtue of his deed and his word, Lincoln was persuaded to admit formerly enslaved African Americans into the United States Civil War effort. And after the war, went back home to Beaufort and got involved. He was an enormous celebrity, in his hometown of Beaufort, and first was elected to the South Carolina House and Senate, did some amazing things there, among which are he wrote the legislation to create the first free compulsory statewide public school system in South Carolina, which was the first such kind of school system without regard to race or class in the United States. And so he did that, and then was elected to Congress and served five terms in Congress. You know, he politically founded the Republican Party of South Carolina, which, of course, at the time was the party of Lincoln, owned a number of businesses and a lot of the real estate down in Beaufort, during Reconstruction. And just generally, I think, you know, committed himself to living a life of consequence.

In the middle of the night, Smalls and the others onboard the Planter traveled through a harbor crowded with Confederate sentries to reach the Union blockade. (Photo: Pi3.124, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: What an amazing story. Admiral Haney, here's a man which although I gather that he wasn't quite enrolled in the United States Navy, nonetheless, was commanding a United States Navy vessel. What do you take away from his story?

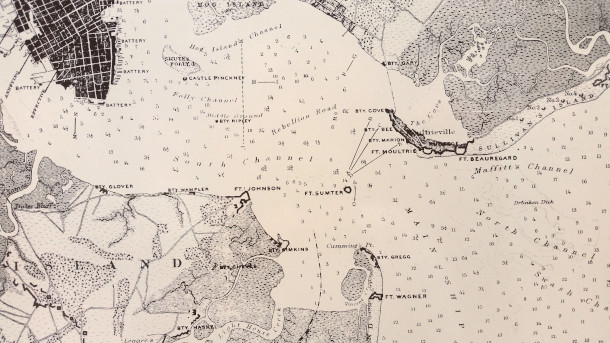

HANEY: Wow, Steve. And just a great story, Michael, and thanks for your articulation of it. I take away, you know, here is an individual that clearly is a self learner, that even though he had the barriers of no education for black folks during that timeframe, and he took it on his own accord to learn at every opportunity he had to even get to the position to be able to do this. The skills required to transit those waters are not trivial, it takes a lot of knowledge and understanding there. So for him to just learn that, first of all, and then take and do the intricate planning, risk analysis, in terms of the things we do today in the military. And then to apply that and execute with confidence. He had to go through multiple checkpoints, and instead of deviating from the normal path, he kept the ship where it would normally be, very close to Fort Sumter as a matter of fact. And if that doesn't give you goosebumps, I don't know what would, you know, if you were thinking about that time with his family on board. So, it's not just having that dynamite available, if it went bad for himself, but for his family, and all those that obviously he had worked very closely with. So that courage, honor, and commitment we talk about today, clearly was part of his fiber back then.

Michael Boulware Moore, Robert Smalls’ great-great grandson. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael B. Moore)

CURWOOD: So, Admiral, talk to us a little bit about how this story resonates with you.

HANEY: You know, I would say a couple of things. My first duty station was Charleston, South Carolina. And it was totally different from where I grew up in Washington, DC. And it's just interesting thinking I had five total years there and operating on two different ships. And it's interesting of how Robert Smalls navigated through in order to get the Planter over to the union and then navigated further through the politics and what he was doing even then. Even before Jim Crow, I find it amazing to be elected, and to be able to make a difference in that regard during that timeframe. It had to be, you know, an amazing individual with a lot of spine, but also a lot of cleverness. Just like he knew the environment he was steaming through with the Planter he clearly knew the environment he was steaming through his work in the Congress.

CURWOOD: So, it's thousands upon thousands of people who were inspired by Robert Smalls. What kind of legacy do you think the Robert Smalls’s story leaves for all people of African descent now in the United States Navy and actually the US military? Admiral Haney?

Admiral Cecil Haney USN (Ret.), the second Black four-star Admiral in the US Navy (Photo: U.S. Department of Defense, Public Domain)

HANEY: I think his courageous example, really shows that regardless of the barriers we face, perseverance, confident thinking, and planning can overcome many barriers. And his lifelong example of that has touched many, both in the military and as you mentioned, outside the military in terms of what he was doing. And I would tend to believe that he had to be articulate and compelling in order to win the day in so many things he was working on, either in an entrepreneurial or in Congress, as well as just convincing that crew to take that risk. I think all of that today gives us an example of which to follow with. And a caring example, because it wasn't just about him and his safety. He was working for the freedom of all those. And then after getting over to the union side years later, continuing to work on the freedom of others. So that's an example of helping mankind above and beyond what you would normally do for oneself.

Links

Learn more about the life and work of Robert Smalls

Check out the Tales of the Talented Tenth series and other books by Joel Christian Gill

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth