June 16, 2023

Air Date: June 16, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

An Urgent Juneteenth Call for Climate Solutions

View the page for this story

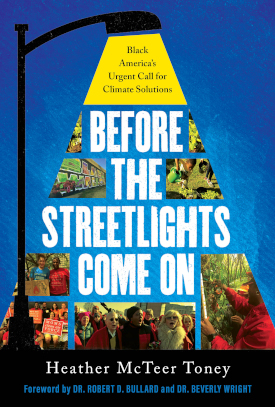

Generations of Black Americans have faced racism, redlining and environmental injustices, such as breathing 40 percent dirtier air and being twice as likely as white Americans to be hospitalized or die from climate-related health problems. So the quest for racial justice now must include addressing the climate emergency, writes Heather McTeer Toney in her 2023 book Before the Streetlights Come On: Black America’s Urgent Call for Climate Solutions. She joins Host Steve Curwood in part one of their conversation. (13:38)

Finding Climate Hope in the Black Vote

View the page for this story

Heather McTeer Toney and Host Steve Curwood continue their conversation about her book Before the Streetlights Come On: Black America’s Urgent Call for Climate Solutions and talk about how faith, voting, and community engagement can help address the climate emergency. (04:56)

Black Courage Upon the Sea: Robert Smalls' Heroic Escape From Slavery

View the page for this story

One night in May of 1862, an intrepid Black man named Robert Smalls commandeered a Confederate ship called The Planter in Charleston, South Carolina and liberated himself and his family from enslavement. His great-great grandson Michael B. Moore and retired four-star Admiral Cecil Haney join Host Steve Curwood to share and reflect on the harrowing story of his escape and life of public service after gaining his freedom. (13:38)

Robert Smalls' Legacy and Liberating Nature

View the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood and guests Michael B. Moore and Admiral Cecil Haney continue their conversation about Robert Smalls and are joined by Joel Christian Gill, a cartoonist and historian who authored a graphic biography about Smalls. They discuss Robert Smalls’ legacy, the current enslavement of nature, and how his courage relates to the courageous action and leadership that is now urgently needed to deal with the climate emergency. (14:24)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230616 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Joel Christian Gill, Admiral Cecil Haney, Michael B. Moore, Heather McTeer Toney.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Celebrating Juneteenth and the freedom to breathe clean air.

TONEY: What better time than Juneteenth to help and let our folks know that we are all free and we can be free from the petrochemical industry and we don't need to be told lies about how this is going to make our lives better when we have history that tells us it is not.

CURWOOD: Also, the harrowing story of Robert Smalls and his escape from slavery and how Juneteenth reminds us how freedom for black people was shortchanged.

ADM. HANEY: Imagine that - slavery ends and you've got over 2 years before we get to Texas. There are many Black folks who didn't understand what Juneteenth was about, much less what Robert Smalls was about.

CURWOOD: That and more this week for Juneteenth on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is the Living on Earth Juneteenth holiday special. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: The Golden Gospel Singers, “Oh Freedom” on A Cappella Praise, Blue Flame Records]

An Urgent Juneteenth Call for Climate Solutions

ExxonMobil’s Baton Rouge Refinery along Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley.” (Photo: Jim Bowen, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is the Living on Earth Juneteenth holiday special. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: The Golden Gospel Singers, “Oh Freedom” on A Cappella Praise, Blue Flame Records]

CURWOOD: On June nineteenth of 1865 enslaved African Americans in Galveston Texas finally got the news that more than two years earlier President Abraham Lincoln had already emancipated three and a half million enslaved people in the Confederate States in rebellion against the Union. By the way, it would take until nearly the end of 1865 for slavery to be outlawed by the 13th Amendment of the Constitution in the remaining slaveholding states like Kentucky, Delaware and New Jersey that had not left the union. But on June 19th of 1866, a year after union troops rode into Texas with the news of freedom, the now free folks in the Galveston area started the Juneteenth tradition of an annual celebration and now it’s a national holiday. And though we’ve come a long way since then, true freedom and equality for all have yet to arrive. Generations of Black Americans have faced racism, redlining and environmental injustices, such as breathing 40 percent dirtier air and being twice as likely as white Americans to be hospitalized or die from climate-related health problems. So, the quest for justice now must include addressing the climate emergency, writes Heather McTeer Toney in her 2023 book Before the Streetlights Come On: Black America’s Urgent Call for Climate Solutions. Black kids were often told to “Get home before the streetlights come on,” words of caution to avoid situations that could endanger young Black lives. Now Heather McTeer Toney is saying black America, along with everyone else needs to take climate action before the darkness of climate catastrophe descends. The former mayor of Greenville, Mississippi, Ms. Toney served as the Southeast Regional Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency under President Barack Obama. And she is now the Executive Director of Beyond Petrochemicals. Welcome back to Living on Earth Heather!

MCTEER: Thanks so much. It's great to be back. Thanks for inviting me back.

CURWOOD: So one of the examples that really opened my eyes to the challenges of both government and officials, when they try to make changes is the North Birmingham story that you tell in your book. You were Region 4 administrator for the EPA, you visited North Birmingham at one point and then you went back. Tell us that story please.

Heather McTeer Toney’s “Before the Streetlights Come On: Black America’s Urgent Call for Climate Solutions.” (Image: Courtesy of Heather McTeer Toney)

MCTEER: So North Birmingham reminded me a lot of my own hometown of Greenville, Mississippi. I was born and raised in the Mississippi Delta, and a community full of love but also full of its own challenges and struggles. So when I was appointed to be regional administrator for EPA in the Southeast, Alabama was part of the community that I served. And North Birmingham, Alabama had been fraught with environmental injustices of a local coke plant and that's not Coca Cola, like the product we drink, but coke which is a byproduct of coal, and burning of coal. And this particular community had been inundated with years of air pollution, so much so that you could feel it in the air and on the street. People talked about how it left a, almost like an itchy filmy residue on the skin. And they had been for a long time asking for help to not only clean the land but also to recognize the impacts of this pollution on their health. There was a high rate of cancer, a high rate of airborne illnesses, asthma, impacts that really were directly related to the air pollution, but nobody, it really recognized it or acknowledged as such. So when I came into the North Birmingham community, it was incumbent upon me as a part of the Obama administration, but also as a part of this community, as an African-American woman born and raised in the south seeing what look like myself, to be as much help as I could be in this space in this moment. So together, we worked on how we could reclaim the land through Brownfields funding. How we could encourage solutions that were created that weren't necessarily connected to environment that people wanted to see done, like revitalizing businesses and schools that have been in that space for a long time. What I did not know was that the state of Alabama and I think historic, and systemic racism that is prevalent throughout our country was going to be just as strongly involved in that space, even with or without me. And there was a very active investigation that was taking place in North Birmingham around bribery; in fact, there were elected officials that were indicted during that time period, all to keep this community from receiving the justice that they really deserve. So it was eye opening to me that it really spoke to the struggles that communities, particularly communities of color across this country face when dealing with environmental justice.

CURWOOD: Yeah, you write in your book that you first rolled through there in the parade of black SUVs, befitting a high federal official, but somebody approached you there and said something.

MCTEER: Yeah, there was a Mr. Smith, who lived in that neighborhood. And I remember we had a community meeting. And he came up to me at this community meeting and I will never forget, he was holding a picture of his deceased loved ones, his family members and he said to me, "So what are you gonna do? What you're gonna do this different than all these other folks" You come up in here, which SUVs, but what are you going to do?". We sort of toured that day, and he came back to me separate, he said, "I want you to do something for me, I want you to come back here, and I don't want you to come back here with all your people. I want you to come back by yourself because they cleaned up for you today, they cleaned up all of the pollution and they cleaned up the streets for you, they washed it all down". He said "but madam administrator you come through here, when ain't nobody looking and then you tell me what you saw". And I did, one trip I was driving in my car coming from my home, going back to Atlanta, and I drove through the back way to get in to the neighborhood and he was absolutely correct. The streets were covered with a film. I stopped and I put my hand like on a fence and I could wipe my hand and could see residue on my hand from what had been blowing over from this coke facility. I went to his house knocked on the door he wasn't at home [LAUGH]. But people know what's happening in their spaces, and we should listen to them more. And that was my experience of understanding the historic legacy of housing discrimination and social injustices that had impacted places like North Birmingham. How real they were today and how much they connect it to environmental justice. And that's what I wanted to write about. I think that was the importance of telling that story in my book, because it connected the dots between legacy pollution, legacy discrimination, and how and why we are experiencing disproportionately environmental injustice in black and brown communities today across this country.

Sugarcane fields in front of the Marathon Garyville refinery in St. John the Baptist Parish, adjacent to St. James Parish, Louisiana. Enslaved African Americans once toiled to grow sugarcane on plantations, and today petrochemical plants are replacing agriculture in the region. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: There's an area colloquially called cancer alley. It's this 85-mile stretch of land along the Mississippi between Baton Rouge and New Orleans and I think there's over 200 petrochemical plants and refineries and now communities there have been speaking out about the plethora of health issues, thinking of cancer and miscarriages that are associated with the constant exposure of chemicals from these plants. And a lot of people living there are descendants of slaves and in fact, some of these plants are next to slave gravesites. What does this tell us about the historic legacy of slavery and environmental justice in the United States that this highly toxic area is a cradle of descendants of slaves?

MCTEER: There is an irrefutable connection between the footprint of enslavement and the travesties that have been placed upon, from African and the enslaved, that is directly related to environmental injustice is that we experience today. Joy and Jo Banner, both sisters that have been working on a project called The Descendants Project in cancer alley I think have expressed this beautifully in their work of protecting the community in the space that they come from, that was subject and still is subject to being the site of a grain elevator. And they have been successful in making sure that the site itself is listed on the eleven most endangered sites by the National Historic Preservation Trust. And the reason they were able to do that was because they were able to show not only is this an 11-mile stretch along cancer alley, that has not yet been inundated by industry that needs to be protected, but also because their ancestors are buried in this space. Every other space along cancer alley, has been impacted negatively by air pollution, land pollution, water pollution, because of this industry, and this industry sits in the exact same footprints that plantation set in all along the coast of Louisiana. There's an Atlantic article that showed this footprint where you could overlay the boundaries of plantations in Louisiana and put on top of that the existing facilities and an almost matched identically. Do you know how scary that is? Let's just think about that for a second, the places where Joy and Joe Banners great, great, great grandfathers were enslaved are the same places that their aunts and cousins work at today, just for a different industry. That really has captured people falsely, because we talk often about the jobs that are brought to these communities be don't talk about the cost. And our communities I think as a whole are being moved to now be a part of the solution and action phase that we're in so that we do not allow industries to continue repeating the same messaging and stories that have negatively impacted our homes.

Heather McTeer Toney is an American politician, environmentalist, and attorney. In 2014, Toney was appointed as a regional administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency for the Southeast region by President Barack Obama. She is now the Executive Director of Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Beyond Petrochemicals Campaign. (Photo: Courtesy of Heather McTeer Toney)

CURWOOD: By the way those plantations in Louisiana were sugar plantations. And sugar made people fabulously wealthy in the way that say the internet boom did. It was a path to a lot of money, although as many as a third of the enslaved persons sold down the river from places like Kentucky and Virginia in the North would, succumb in the frequent yellow fever epidemics.

MCTEER: Yes.

CURWOOD: So, we're speaking at the time of Juneteenth. What can we learn about the petrochemical industry and its impact on environmental justice as we move forward with the celebration?

MCTEER: The beauty of Juneteenth and the fact that our United States of America acknowledges this as a federal holiday. Enslaved Africans were in Texas when they got that message. so that they were no longer enslaved but we're now subject to the same rights and liberties is the rest of us across the United States that had been freed. And today in Texas, this is where there is an extraordinary amount of petrochemical facilities that are already seated, but also a place where people are being falsely told that this will be an improvement to their lives, versus the reality of the chemical impacts, the environmental injustices, the travesties that take place to the human body by putting more chemicals into this space. So, what better time than Juneteenth to help and let our folks know that we are all free and we can be free from the petrochemical industry. We don't need more of the industry to be placed in communities, particularly communities of color, but we certainly don't need more plastics in our body. We don't need more economic disparity and we don't need to be told lies about how this is going to make our lives better when we have history that tells us that it is not.

Related links:

- Learn more about Heather McTeer Toney and her book “Before the Streetlights Come On: Black America's Urgent Call for Climate Solutions”

- CNN | “A Quarter of Americans Live with Polluted Air, With People of Color and Those in Western States Disproportionately Affected, Report Says”

- The Atlantic | “Louisiana Chemical Plants are Thriving off of Slavery”

- Learn more about the Descendants Project

[MUSIC: Carolina Chocolate Drops, “Peace Behind the Bridge” on Leaving Eden, by Etta Baker, Nonesuch Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up our Juneteenth holiday show continues with Heather McTeer Toney and her call to use the ballot box to help save our climate. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Carolina Chocolate Drops, “Peace Behind the Bridge” on Leaving Eden, by Etta Baker, Nonesuch Records]

Finding Climate Hope in the Black Vote

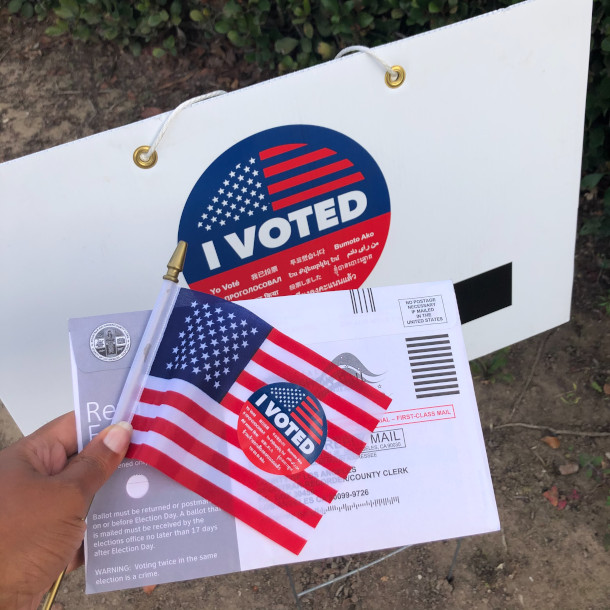

Black and Brown people are more likely than any other demographic to vote on environmental issues, according to a study conducted by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. (Photo: Janine Robinson, Unsplash, Fair Use)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

I’m back now with Heather McTeer Toney, a former EPA regional administrator, now with Beyond Petrochemicals and author of the book Before the Streetlights Come On: Black America’s Urgent Call for Climate Solutions.

CURWOOD: What can we learn from the recent elections about the power of the black community when it does come to voting, especially with environmental issues? In Georgia, for example, research showed that a considerable number of people of color came out to vote, even people who hadn't voted before and they had a very strong connection to concerns about the environment. In fact, some surveys show that black and brown people are among the most concerned of registered voters about the environment.

MCTEER: Absolutely.

CURWOOD: So, what about voting as a solution to the problem of environmental injustice?

MCTEER: Absolutely. That was a Yale study that showed black and brown people are more likely than any other demographic to vote on environmental issues. It's also the demographic that's the most attacked, because over the past three years, the number of pieces of legislation that have attempted to be passed through in states where they have limited who can vote, how they can vote, and where they can vote, is targeted specifically to the demographic of people that will turn out to vote the most for environmental issues. Which is why I tell everyone at the end of every single one of my chapters, make sure you vote do everything that you can vote, it is one of the most powerful levers that we have to be able to speak to how environmental policy is shaped and putting the right people in office to shape that policy.

Petrochemical plants near residential neighborhoods in “Cancer Alley” along the lower Mississippi River in Louisiana. (Photo: Courtesy of Deep South Center for Environmental Justice)

CURWOOD: Towards the end of your book, you have some fascinating numbers, you say that about 75% of African Americans say that religion is an important part of their lives, compared to less than half of whites and maybe a bit more for Latinos, even 40%, among younger Black people. And the large environmental movement in this country is fairly agnostic. I'm not sure that I've been to a major environmental advocacy gathering where people have stopped to pray in advance. Now, we know that social movements in this country had been led, I think the civil rights movement, of course, coming out of the churches. There's a Reverend in front of Martin Luther King Jr's name. How can the connection be made to really engage the Black community, those who are church going to take on this whole question of the climate emergency, the toxics emergency and bring their strength to the table? Because I only see them in little bits and pieces right now?

MCTEER: Yeah, it is the sleeping giant, it really is. And I think it's gonna take us seeing environmental action, climate action, and civil rights action, because you're absolutely right in the civil rights movement was so staunchly led by the community of faith. It's hard to not connect Earth and nature to your responsibilities for being a Christian.

CURWOOD: You mean caring for creation. So, what can be done to change that? You call it a sleeping giant, what can be done to wake up the sleeping giant?

Heather McTeer Toney alongside other environmental activists including Jane Fonda during a Fire Drill Friday Climate Strike in Washington D.C. (Photo: Courtesy of Jose Luis Magana for Moms Clean Air Force)

MCTEER: I think it is encouraging and giving space and freedom to do it. Green the Church is growing every single day. Interfaith Power and Light, an organization that has been infusing faith and climate action, and now we're beginning to see it on the right, so much that there's like evangelicals for the environment. We're coming to this place of having to have climate hope and if there's any entity on this planet, that brings hope is the faith-based community. And faith-based community regardless of faith, we think about our Muslim brothers and sisters, Christians, Jews, Hindus, there's always this element of faith that speaks to the hope of tomorrow. Climate issues have been framed as such an existential crisis that is so big, people feel hopeless, they don't they don't see a path out of it. Faith requires the hope of us every single day living our lives and that there is a hope for future generations, a hope in tomorrow, and that we have a responsibility and connectivity to that. So, I think the more that we say that, the more that we bring to bear our responsibilities from spaces of hope and do that in a way that is open, it is fearless and it is connected to science, the more people feel comfortable, and we're able to talk about some of those solutions.

CURWOOD: Heather McTeer Tony is executive of Beyond Petrochemicals and author of the book Before the Streetlights Come On: Black America's Urgent Call for Climate Solutions. Thanks so much, Heather, for taking the time with us today.

MCTEER: Thank you.

Related links:

- Learn more about Heather McTeer Toney and her book “Before the Streetlights Come On: Black America's Urgent Call for Climate Solutions”

- CNN | “A Quarter of Americans Live with Polluted Air, With People of Color and those in Western States Disproportionately Affected, Report Says”

- The Atlantic | “Louisiana Chemical Plants are Thriving off of Slavery”

[MUSIC: Elizabeth Cotton, “Freight Train” on Freight Train and Other North Carolina Folk Songs and Tunes, by Elizabeth Cotton, Smithsonian Folkways Records]

Black Courage Upon the Sea: Robert Smalls' Heroic Escape From Slavery

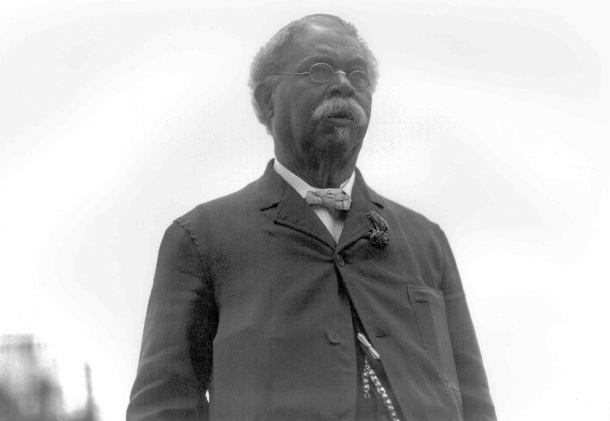

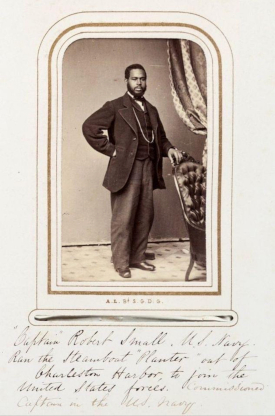

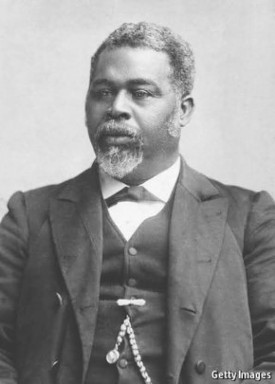

After freeing himself and his family from slavery in a daring maritime escape, Robert Smalls enlisted as a ship pilot with the Union. Following the Civil War, he returned to South Carolina and embarked on a political career. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael B. Moore)

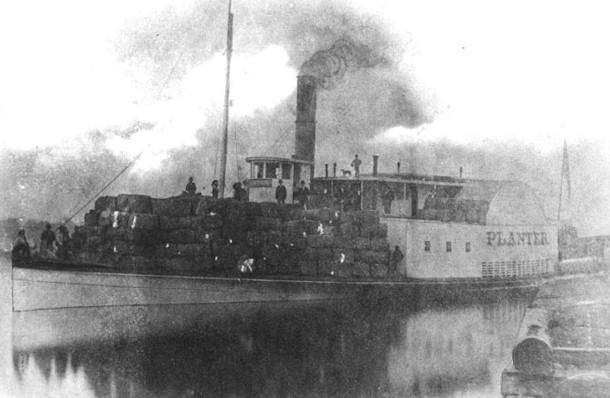

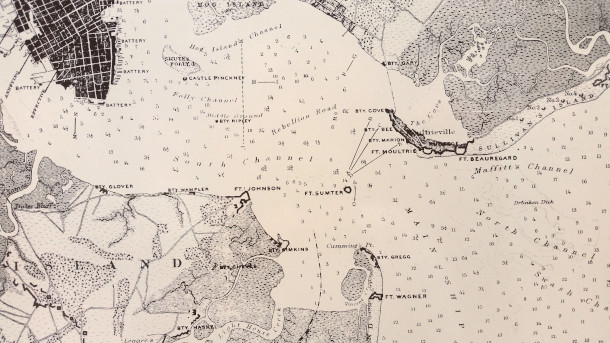

CURWOOD: If hope sometimes feels impossible in the face of climate disaster, imagine how remote hope for a better future would have seemed for the African Americans enslaved in this country over more than 200 years. And yet, some did dare to dream of a free life for themselves and their families, and a few even risked everything to escape. Their courage serves as a reminder that even in the most adverse of circumstances, a way forward is possible. As we continue our celebration of Juneteenth and emancipation, we turn now to an astonishing story of courage when a brave black man named Robert Smalls and his friends commandeered a confederate ship and steered themselves and their families to freedom one night in May of 1862. His great-great grandson Michael B. Moore, a business leader and author, joined two other special guests for our live Juneteenth event in 2022. Admiral Cecil D. Haney, now retired, was the second Black four-star admiral in US Navy history and served as Commander of the United States Strategic Command for three years, in addition to commanding the US Pacific Fleet before that. And Joel Christian Gill is a cartoonist, historian, and author of a graphic biography of Robert Smalls. Robert was born into slavery in 1839 to a mother who served the white masters of a house in seaside Beaufort, South Carolina. He grew up with more autonomy than many of his peers and had a streak of independence that sometimes got him into trouble. As a young teen, Robert Smalls was caught in the streets after the curfew at night fall for Black people and arrested. But he was able to talk his way out of a whipping and got off with just a stern warning, though his master later sent him off to be hired in Charleston where he was allowed to keep a small amount of his wages. Robert Smalls was ethnically Gullah Geechee, a society of African descendants along the coast and sea islands of the Carolinas, Georgia, and North Florida. And his familiarity with the sea would become his key to freedom via a ship called The Planter. His great-great grandson Michael B. Moore shares the amazing story of how Robert Smalls took his fate into his own hands.

While enslaved, Smalls piloted a steamship called the Planter . In an incredible feat, he took control of the ship and steered himself and his family, as well as his fellow crewmembers and their families, to freedom. (Photo: Naval History and Heritage Command, Public Domain)

MOORE: Yeah, he was working on the Planter. And you know, as fate would have it, the Planter, because of its value, was taken over by the Confederate Army once the Civil War began. And he was its pilot, he moved up the ranks and ended up being the pilot, as I understand it back then. Clearly he was not the captain of that ship, but he was the person who was sailing the ship, maneuvering the ship, here and there. And so he knew how to sail the ship. He knew the ins and outs of the waterways of the low country. And personally, he was in his low 20s: 23, 24. He was married, he had two young children. And he was just a father, a husband, he loved his family. And he knew that just the reality of slavery was that his family, his wife, his children could be sold away from him in an instant. And so he thought, you know, very deeply about how to do something about that. One of the things that he did, you know, Robert, as mentioned, he was hired out, he got a salary that he sent back to his master in Beaufort, but he was able to keep a dollar a week. And with that dollar, he bought various sundries, tobacco, candies, fruit that he then sold on the docks. And he saved every penny and ended up negotiating for the life of his wife and children with his wife's master. He put down a hundred-dollar down payment on the life of his family with a total sort of purchase price of about $500. But that was precarious. He knew how long it took him to earn that much money to save up that much money. And so he knew that there was a United States blockade, a federal blockade just outside the mouth of the harbor. And he knew that if he could somehow figure out a way to get there, that he'd be free.

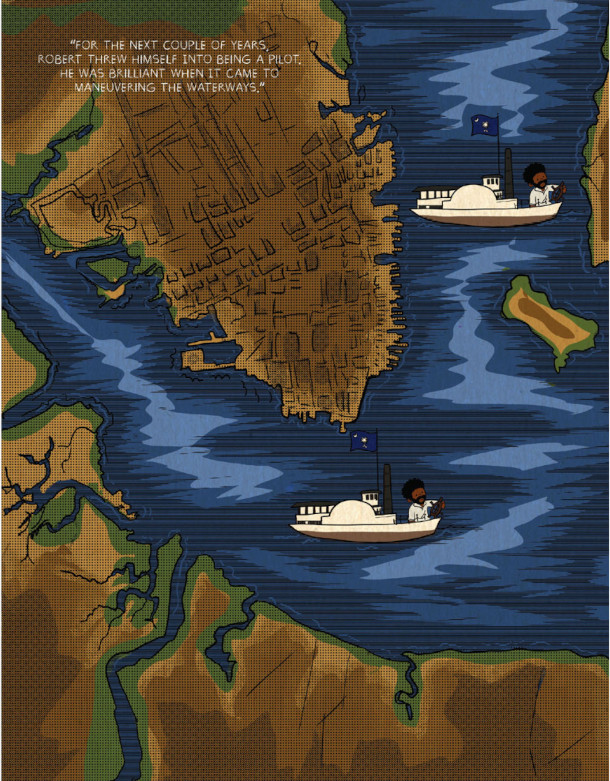

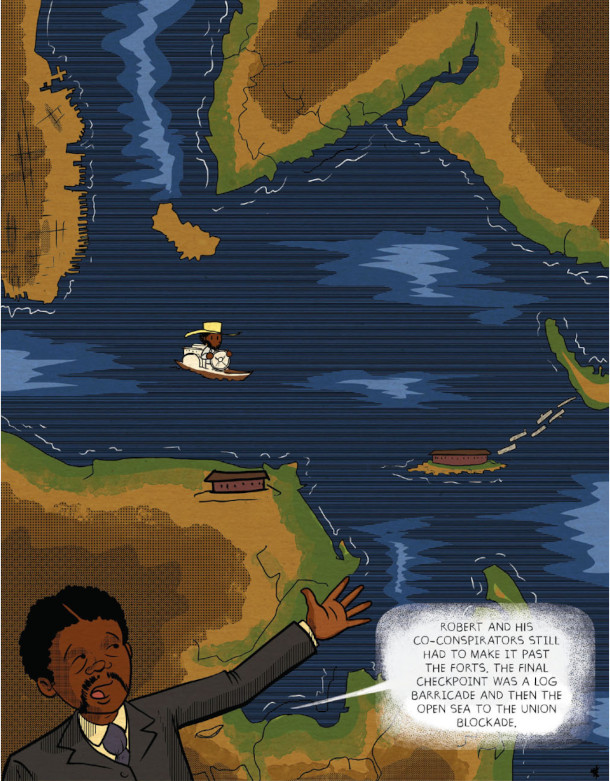

Smalls had become an expert at navigating complicated waters during his time as pilot of the Planter. Above, a page from the graphic biography Tales of the Talented Tenth No. 3: Robert Smalls, by Joel Christian Gill. (Photo: Courtesy of Joel Christian Gill)

And so he noticed that the Confederate crew from time to time would leave for the night. They weren't supposed to, but they would leave for the night, not to come back until the next day. And he concocted a plan. He got together the other enslaved crew of the Planter, and came up with a plan that one night, it ended up being the night of May 12, 1862 into the morning, the early morning hours of May 13. The Confederate crew left, he got his family, the enslaved crew and their families. He famously sort of donned the top hat and this long overcoat of the Confederate captain of the Planter and got up into the wheelhouse and he was able to sort of mock, as the story goes, the Confederate captain had a, you know, an unusual noteworthy kind of gait, about him. And at distance, and in the middle of the night, Robert was able to mock that, mimic that. Because he was the pilot of the boat, he knew the pass codes to get past the four or five forts in Charleston Harbor. And he essentially bet everything he had on everything he dreamed of and won. They lined the bottom of the boat with dynamite, they knew that if they had gotten caught, that they would be executed probably in a particularly gruesome way as an example, you know, for others who might have that kind of an idea. And so it was a life or death proposition. I often think, you know, it is so complicated, I imagine, in the dead of night to sail a boat through, you know, a busy and complicated harbor. But to do that, under the threat of, of death, if something were to go wrong, you know, it's an amazing challenge. And I often think you know, that if something had gone wrong, I mean, clearly, I would not be here. So, I have lots to thank Robert Smalls about, but certainly his bravery and his skill are among the top.

CURWOOD: So, what happened to Robert Smalls after he got his family to freedom? I imagine the union folks on the boat were pretty surprised to see this confederate ship sailing towards them, but I gather they didn't fire, huh?

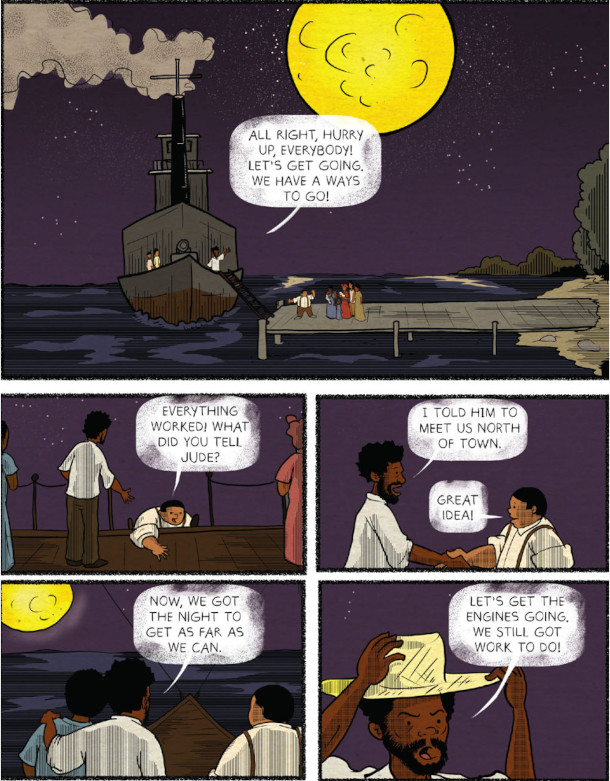

Preparing for the night’s journey through the harbor, from Tales of the Talented Tenth . (Photo: Courtesy of Joel Christian Gill)

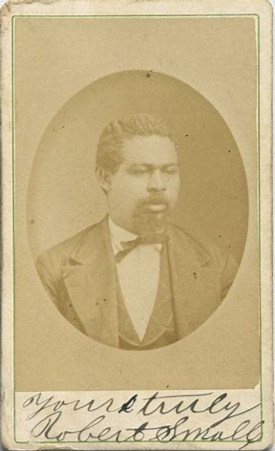

MOORE: Yeah, as the stories go, Robert had thought through all the details. He had thought through, you know, all of the intricacies of getting to freedom to that blockade, except for one detail, which was here is this they say one of the largest boats in the harbor, you know, steaming full steam ahead toward this huge blockade with an enormous confederate flag. And so he had forgotten that detail. So very quickly, they lower the Confederate flag. My great great grandmother, Hannah had thought about that detail, though, thankfully, and had sewn together a number of bedsheets into the universal white flag of surrender. And that saved them because they also, they could have gotten past all of the Confederate forts but then also, you know, run into trouble with the union blockade and gotten killed by them. So yeah, it was a precarious, audacious kind of a plan and, you know, God was with them. You know, Robert got a reward for delivering the Planter to the United States. He didn't actually get sort of the equation of what Congress sort of prescribed for these matters, I think they couldn't see fit to give a black man that much money, but he got a handsome reward. And he was received up and down the east coast as a hero, one of the first real heroes of the Civil War. And he could have lived a very comfortable, happy life as a civil war hero. But instead, he decided to go back into the crucible of the war effort, he freed himself, he freed his family, but he also wanted to free others like him who were enslaved and came back and fought actually on the Planter. Again, as the story goes, he became the first African American to command a United States Naval Vessel, became a captain of the Planter, fought in 18 battles, was taken by Admiral S.F. Du Pont to Washington to meet with President Lincoln and Secretary of War Stanton. And as the story goes, by virtue of his deed and his word, Lincoln was persuaded to admit formerly enslaved African Americans into the United States Civil War effort. And after the war, went back home to Beaufort and got involved. He was an enormous celebrity, in his hometown of Beaufort, and first was elected to the South Carolina House and Senate, did some amazing things there, among which are he wrote the legislation to create the first free compulsory statewide public school system in South Carolina, which was the first such kind of school system without regard to race or class in the United States. And so he did that, and then was elected to Congress and served five terms in Congress. You know, he politically founded the Republican Party of South Carolina, which, of course, at the time was the party of Lincoln, owned a number of businesses and a lot of the real estate down in Beaufort, during Reconstruction. And just generally, I think, you know, committed himself to living a life of consequence.

In the middle of the night, Smalls and the others onboard the Planter traveled through a harbor crowded with Confederate sentries to reach the Union blockade. (Photo: Pi3.124, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: What an amazing story. Admiral Haney, here's a man which although I gather that he wasn't quite enrolled in the United States Navy, nonetheless, was commanding a United States Navy vessel. What do you take away from his story?

HANEY: Wow, Steve. And just a great story, Michael, and thanks for your articulation of it. I take away, you know, here is an individual that clearly is a self learner, that even though he had the barriers of no education for black folks during that timeframe, and he took it on his own accord to learn at every opportunity he had to even get to the position to be able to do this. The skills required to transit those waters are not trivial, it takes a lot of knowledge and understanding there. So for him to just learn that, first of all, and then take and do the intricate planning, risk analysis, in terms of the things we do today in the military. And then to apply that and execute with confidence. He had to go through multiple checkpoints, and instead of deviating from the normal path, he kept the ship where it would normally be, very close to Fort Sumter as a matter of fact. And if that doesn't give you goosebumps, I don't know what would, you know, if you were thinking about that time with his family on board. So, it's not just having that dynamite available, if it went bad for himself, but for his family, and all those that obviously he had worked very closely with. So that courage, honor, and commitment we talk about today, clearly was part of his fiber back then.

Michael Boulware Moore, Robert Smalls’ great-great grandson. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael B. Moore)

CURWOOD: So, Admiral, talk to us a little bit about how this story resonates with you.

HANEY: You know, I would say a couple of things. My first duty station was Charleston, South Carolina. And it was totally different from where I grew up in Washington, DC. And it's just interesting thinking I had five total years there and operating on two different ships. And it's interesting of how Robert Smalls navigated through in order to get the Planter over to the union and then navigated further through the politics and what he was doing even then. Even before Jim Crow, I find it amazing to be elected, and to be able to make a difference in that regard during that timeframe. It had to be, you know, an amazing individual with a lot of spine, but also a lot of cleverness. Just like he knew the environment he was steaming through with the Planter he clearly knew the environment he was steaming through his work in the Congress.

CURWOOD: So, it's thousands upon thousands of people who were inspired by Robert Smalls. What kind of legacy do you think the Robert Smalls’s story leaves for all people of African descent now in the United States Navy and actually the US military? Admiral Haney?

Admiral Cecil Haney USN (Ret.), the second Black four-star Admiral in the US Navy (Photo: U.S. Department of Defense, Public Domain)

HANEY: I think his courageous example, really shows that regardless of the barriers we face, perseverance, confident thinking, and planning can overcome many barriers. And his lifelong example of that has touched many, both in the military and as you mentioned, outside the military in terms of what he was doing. And I would tend to believe that he had to be articulate and compelling in order to win the day in so many things he was working on, either in an entrepreneurial or in Congress, as well as just convincing that crew to take that risk. I think all of that today gives us an example of which to follow with. And a caring example, because it wasn't just about him and his safety. He was working for the freedom of all those. And then after getting over to the union side years later, continuing to work on the freedom of others. So that's an example of helping mankind above and beyond what you would normally do for oneself.

Related links:

- Watch Living on Earth’s 2022 live event, “Black Courage Upon the Sea: A Juneteenth Celebration of Robert Smalls”

- Learn more about the life and work of Robert Smalls

- Check out the Tales of the Talented Tenth series and other books by Joel Christian Gill

- Purchase Tales of the Talented Tenth No. 3: Robert Smalls (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Elizabeth Cotton, “Wilson Rag” on Freight Train and Other North Carolina Folk Songs and Tunes, by Elizabeth Cotton, Smithsonian Folkways Records]

CURWOOD: That’s retired Four-star Admiral Cecil Haney and coming up after the break, we’ll meet Joel Christian Gill, a cartoonist and historian who authored a graphic biography of Robert Smalls. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Elizabeth Cotton, “Wilson Rag” on Freight Train and Other North Carolina Folk Songs and Tunes, by Elizabeth Cotton, Smithsonian Folkways Records]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Hot Club Sandwich, “Swang Thang” on No Pressure, by David Grisman, self-published]

Robert Smalls' Legacy and Liberating Nature

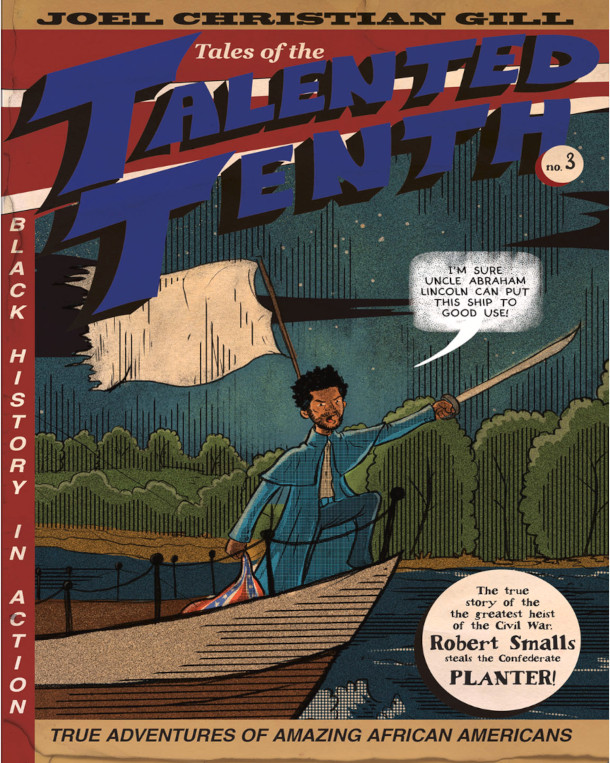

The cover of Tales of the Talented Tenth No. 3: Robert Smalls, by Joel Christian Gill. (Photo: Courtesy of Joel Christian Gill)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: We’re back now with more from our discussion about the amazing story of Robert Smalls, who escaped from slavery in 1862 by piloting a commandeered Confederate ship past Fort Sumter into the Union blockade lines and freedom. Artist and historian Joel Christian Gill was so inspired by Robert Smalls’ story that he decided to make it the focus of the third volume of his graphic biography series Tales of the Talented Tenth. By the way, the term “Talented Tenth” was coined by a white philanthropist and popularized by W. E. B. Du Bois in a 1903 essay. Du Bois argued liberal college educations for Black elites would uplift all African Americans in society, in contrast of the views of Booker T. Washington who called for as many former slaves and their descendants as possible to get vocational educations. Joel Christian Gill, why do you find Robert Smalls’ story so compelling?

GILL: I mean, what doesn't attract you to Robert Smalls's story? Right? Like when you think about, like how in America, we've sold this idea, this fiction of the Horatio Alger story. Like there's this person who by great deeds of himself, he, he does something and he becomes a rich and wealthy man. That ain't real, right? But it is real for black people, right? And specifically for black people, enslaved Africans like Smalls. He was less than nothing. He was property. And by the strength of his character and his will, he made a way for himself. And like what's amazing, in a short period of time, he went from being an enslaved African, he probably couldn't read in that time. And then about a four- or five-year span, he saves his family, 13 other people, which is like the greatest heist of this Confederacy, right? That's like the equivalent of millions and millions of dollars, right? So he steals all these people and the ship. That would have been an amazing story in and of itself, but then he becomes a war hero. He saves the Planter from being destroyed when the captain, he took refuge in the engine room.

In March 2023, the U.S. Navy renamed a ship, formerly named after a battle won by the Confederacy, the USS Robert Smalls. (Photo: U.S. Navy, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: This was one of the Civil War battles, right?

GILL: Yeah. In one of the battles afterwards. You know, he does this, and then he becomes a politician. And what I think is really amazing, which we don't spend a lot of time in America talking about the idea of what these black Republicans were doing in reconstruction is that they were not focusing on what black people needed. They were building things for everybody. Like that law that he wrote that funded and made compulsory education in South Carolina statewide. That was for everybody. That wasn't just for black people. That was for everybody. And I think it's those kinds of things. There's one instance and I keep mixing it up. I don't know if it was Georgia or South Carolina, but the black Republicans were ejected from the Senate and the House. And when Ulysses S Grant comes back, and reinstates them, the first thing those black Republicans do is to pay for the people's time that were illegally sitting in their seats. Right, like the ultimate turning the other cheek. So, when you look at the period of reconstruction, it was like the first time in America, where we had a real clear and definitive time where we could have had pure and true racial justice in America that was destroyed by white supremacy. And I think that's the sad thing about that is because we put traitors on the names of our schools, like, you know, people who would have legitimately killed an American President, that would have been Robert E. Lee, or Fort Hood, you know, like any of these things that we're naming these Confederate generals after. These we're not Americans, they died not American citizens, and most of them gave up their American citizenship. But we have Robert Smalls, who embodies the American ethos of what it is to pull yourself up by your bootstraps. And also do things and provide service to the other people. And there's not a school in America that's named after him. Like where are the statues for Robert Smalls? And for folks like Robert Smalls, Blanche Bruce and Hiram Revels? Where are those people in our history? Because black people in America make America keep her promises. When we do things and when you do these things, it actually helps everybody, not just black people. And I'm just like, that's what attracted. I'm sorry, I'm on, I'm on a soapbox.

A page from Tales of the Talented Tenth No. 3: Robert Smalls. (Photo: Courtesy of Joel Christian Gill)

CURWOOD: Well, no, wait. So, I think to all of you here, the point that Joel has made is that Robert Smalls moved to have education for everyone to lead all people in South Carolina for better education. What is it that black America can do to make a better place for all of us? Because spoiler alert, I think we're still dealing with the white supremacy thing.

GILL: I think it's just continuing to demand more and to not, like for example, not accept things like Juneteenth. Right? You know, I say this a lot. And you know, if anybody's ever heard my rant, I always say like, it's like black people in America are in prison. And we're saying, hey, please let us out, please let us out. And they say, well, we'll give you a cake. So, you can have cake while you're in prison. And that's, that's what Juneteenth is, right? Like, I don't need a holiday to cook out. I can do that by myself. Right? And we've all been doing it right. Juneteenth has been a holiday for black people, for at least last 150 years. We didn't need the federal government to say it was a holiday, we've been drinking red strawberry soda, and cooking out and dressing in fancy clothes for a long time. We didn't need that. Right? What we needed was the end of mass incarceration. What we needed is like an acknowledgement of the wealth gap. What we need is like speaking about environmental issues. Look at poor health outcomes of black people in communities where there's pollution, right? We don't do stuff like that. We don't deal with environmental racism. We don't deal with any of these things. We just say, oh, but you got Juneteenth now. So, we're gonna give you some cheesecake ice cream and everything's gonna be okay.

Returning to South Carolina after the war, Smalls was elected to the state House and Senate, and then to the U.S. House of Representatives. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael B. Moore)

CURWOOD: All right.

MOORE: Yeah, I would jump in and say I think you know, the story of Robert Smalls presents an appropriate model for how people who care about justice, who care about, you know, equality, you know, just how we need to act. Robert didn't just sort of sit back on his laurels and he deserved to relax and to live a really comfortable life, but he rolled his sleeves up and he got back into the fight. And he continued to try to do what he could to influence the process and to make America live up to her promises. And so, you know, I think democracy is, you know, a contact sport. It's a participative sport, like we've all got to be involved and got to pay attention. And so I think, Robert's example of coming from nothing, coming from, in some ways beneath nothing, and just striving and working and having his eyes fixed on a, an appropriate point on the horizon. I think that's something that can resonate with people today.

During his time in government, Smalls wrote legislation to create a free and compulsory education system statewide, the first of its kind in the U.S. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael B. Moore)

HANEY: Yeah, I agree. I think two points, the example of Robert Smalls and others like him, that had some incredible barriers placed in front of them, took advantage learned as much as they could, even without formal education, in order to reach a goal. And then after getting to that goal, went to work hard for the well-being of others, including others that didn't look like them. And you can look at that and say, Jim Crow, sort of compressed that. And then there's, you know, follow on rebounds and what have you. But I think we have to continue to talk about that, just like this program gives that exposure. I would argue a little bit differently with Juneteenth in that, with that recognition of a holiday, there are many black folks that didn't understand what Juneteenth was about, much less would Robert Smalls is about. So, if you don't have something like that, that puts a bit of an exclamation mark, a pause and say, let's talk about this. It gives more recognition to it. Imagine that. Slavery ends and you got over two years, before we get to Texas. A lot of understanding has to be digested there. And then with the spirit of Robert Smalls is we can't stop. We can't let those barriers just stay in front of us. We have to continue to self-educate, thrive, thirst for knowledge, and then work our way through and continue to press forward with it. And prayerfully, eventually we'll get there.

GILL: Yeah, I think you know, Dr. King said, the moral arc of history was long, but it bends toward justice. And I just think we need to pull it. We need to legitimately reach over and pull that toward us. And of course, if they had given me an opportunity to vote for Juneteenth, or Dr. King's holiday, or Black History Month, I would have voted for all of those things, right? But what those things do is they allow people to forget. To not have to pay attention. We would like the reflection, but we also want voting rights for people in South Carolina. And like those kinds of things, like, let's do some police reform, let's do some things that you know, like we can see racism happening in health outcomes, right? So we can see that this is actually physically affecting black people in America. And while, I love the fact that these people are saying, let's reflect on these things. But also, like, let's do something.

The house in Beaufort, South Carolina, where Smalls was born into slavery in 1839. He later purchased the house and lived there for the rest of his life. (Photo: National Park Service Southeast Regional Park Office, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Well, this has been an amazing discussion. Perhaps we could go out and talk green for a moment, not just black and white, but green. Our society has enslaved nature, the way that people were enslaved in chattel slavery. And we have this resource-extraction mindset that we burn fossil fuels. And we do things that our society acts as if it's okay to do this, when in fact, if you look at the natural balance, it's not. Because by taking all that stuff that was put away millions of years ago, and putting in the atmosphere now, we are wrecking the kind of environment that us humans operate in, right? So, looking back at the story of Robert Smalls, and looking ahead, how can we break the chains of our enslavement to this totally dysfunctional, destructive way of handling our environment and most manifest right now by climate disruption? What are the tools that he showed us that all people could use now? How can we get ahead of this, or at least stay even with it?

Smalls served five terms in the U.S. Congress. His time in government was cut short by a violent, white supremacist campaign to dismantle Black political power and civil liberties. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael B. Moore)

GILL: I'll just say something really quickly, I don't think we can rely on predatory capitalism to get us out of something that predatory capitalism got us into. So that means like, electric cars are not going to do it, you know, it's mass transit, that's going to decrease our dependency on carbon, right? Like, it's that kind of thing. We're gonna have to look for policies that are not about just a new, different way to make money. But we're going to have to do some things that are not involved in the market in and of itself, because when we don't have a Wall Street, when Wall Street is underwater, it's not going to matter what their market driven solutions, right? So, we're going to need to find solutions that are not necessarily based on predatory capitalism, which is what we're living in right now.

MOORE: Well, I'll take it from just the standpoint of just reiterating the fact that you know, I think the lesson that Robert Smalls showed us is that you know, amazing things can be done, created, established with vision, and with the audacity of hard work and just diligence. You know, one of Robert's perhaps most famous quotes was "my race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of anyone anywhere, all they need is an equal chance at the battle of life." And I think even if you take a step back and broaden that, from focusing on people of African descent to sort of people in general, I think, to the point about predatory capitalism, you know, at the end of the day, the people have to create a meaningful counterbalance to so much of self-interest and greed, that is not good and not serving humanity.

CURWOOD: Admiral?

Speakers at the Living on Earth live event also discussed what Robert Smalls’ heroic work can teach us about fighting for racial and environmental justice today. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael B. Moore)

HANEY: I will try to approach it in a different sort of way. And I'll try to use Robert Smalls' example, and just this Planter approach that he had. You know, he had to convince a lot of people. I mean, the people that were part of his crew, to go forward against the risks that was in front of them, which meant he had to be a compelling leader, a thought leader, and a planning leader, who gave it probably a lot of introspection himself in going forward. So, when I look at this, looking at the concerns we have for our environment today, getting at it, it gets to be understanding the problem. I think about where we were in the Al Gore days to where we are today. And still, we have a long ways to go. And a lot of navigating to get there. It requires a lot of education and exposure. And being able to have that compelling argument out there in terms of we gotta go forward, and the emergency of fixing some things. And I think his example, can show us some of that, but then it's got to be expanded more, it's not just the United States and what have you. It's the world and how the world addresses this problem collectively, and recognizes it as a problem, really requiring leadership in a different way than we perhaps have had before in terms of this urgency of applying resources to it. It's interesting seeing the world look at COVID and the amount of money thrown into research, development, and what have you there to come up with vaccines and to study it, to understand and medicinals to get at it. Even for those who don't believe in the vaccinations to be able to help them. Well, that was a worldwide effort in many ways. That must continue. We have to have a real compelling worldwide effort going on in this area in so many of the facets that were discussed here. You know to get at this and the uncertainty of our future if we don't.

CURWOOD: You know, Admiral, it's just like you say here. With Robert Smalls, his choice was now or never. Our chance now with the climate is now or never.

[MUSIC: Elizabeth Cotton, “Vastopol” on Freight Train and Other North Carolina Folk Songs and Tunes, by Elizabeth Cotton, Smithsonian Folkways Records]

CURWOOD: Retired Four-Star Admiral Cecil Haney, Robert Small’s direct descendant Michael B. Moore and author Joel Christian Gill discussing the self-emancipation and legacy of Robert Smalls and what we can draw from this story for the challenges of our own time. For the full video of their Juneteenth Live Event with Living on Earth please visit loe.org/events

Related links:

- Watch Living on Earth’s 2022 live event, “Black Courage Upon the Sea: A Juneteenth Celebration of Robert Smalls”

- Learn more about the life and work of Robert Smalls

- Check out the Tales of the Talented Tenth series and other books by Joel Christian Gill

- Purchase Tales of the Talented Tenth No. 3: Robert Smalls (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Elizabeth Cotton, “Vastopol” on Freight Train and Other North Carolina Folk Songs and Tunes, by Elizabeth Cotton, Smithsonian Folkways Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Swayam Gagneja, Madison Goldberg, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Clare Shanahan, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@org. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening! And Happy Juneteenth!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth