Lowballing Sea Level Rise

Air Date: Week of July 21, 2023

More than half of the U.S. cities and states that Andra and her colleagues examined in their study underestimated the upper end of possible sea level rise, compared to forecasts by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (Photo: Wade Austin Ellis, Unsplash, Unsplash License)

Many U.S. states and cities are underestimating how much the seas could rise even as they plan long term infrastructure, according to a study. Lead author Andra Garner of Rowan University joins Host Steve Curwood to explain why the moving target of climate impacts is confounding some planners.

Transcript

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Almost a third of the U.S. population lives along the coast, where rising seas are already flooding streets and contaminating groundwater. Because of geography and how heat is distributed in the oceans, sea levels don’t rise equally everywhere. To prepare for the future and protect critical infrastructure, communities need to predict how bad it’ll be along their coastlines. But a study from early 2023 compared these projections to numbers from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and found that many U.S. states and cities are underestimating how much the seas could rise. Here to tell us more about this research is Andra Garner of Rowan University, lead author of the study. Welcome to Living on Earth, Andra!

GARNER: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So, what did you find when you compared the local projections to the IPCC report?

GARNER: One of the big takeaway things that we found was that over half of the locations in the U.S., the local projections were just not quite keeping pace with the higher amounts of sea level rise from the IPCC. And, you know, that could be just that they're not looking at a high enough emissions scenario to match those higher emissions scenarios from the latest IPCC report. Or maybe they're not looking at a full range of the possible future projections. And I think that's one thing that this paper really illustrated, is, you know, everyone has the same information available to them, but how you deal with it and the decisions you make along the way result in different approaches to planning for sea level rise.

Rising seas can erode coasts, send saltwater into aquifers, and worsen flooding. Above, high tide inundates a street in Florida. (Photo: Dave, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: I mean, there's some places -- I'm thinking of Savannah, Georgia, parts of the Mississippi Delta -- that have projections for 2100 that are a meter, or more, lower than the IPCC's. You know, that's like three feet. What's the problem with cities and states underestimating the high end of possible sea level rise? I mean, why is it so important for coastal communities to consider the high end when they plan for the future?

GARNER: If you think about it -- use an analogy. If you were going to go on vacation, and you look up the forecast for where you're going on vacation, and you see that it is supposed to be sunny every single day, you still might want to pack an umbrella in your luggage, because we know forecasts have some uncertainty. That could change, you might get caught in the rain, and you don't want to have to run out and find an umbrella while you're on vacation. Kind of the same idea applies for sea level rise projections. You know, we can look at what's most likely, but when it comes down to planning, and especially when we're thinking about, you know, really critical infrastructure, things like power plants or hospitals, we might want to be taking a more cautious approach than what's most likely. It's going to be even more costly to try to go back and retrofit our infrastructure and try to adapt on the fly than if we had kind of been planning all along for those potentially higher amounts of sea level rise.

CURWOOD: Looking over your data, I noticed that there were no projections of sea level rise offered by communities in the South after the year 2100. You know, a baby born today probably is going to be living past that period of time.

GARNER: Yeah, that was one of the other big takeaways is that, you know, to not have those longer-term sea level projections is concerning, certainly in any location around the country, but in the U.S. South is especially concerning, perhaps, because there have been other studies that have looked at how flooding will change around the country, and have found that, particularly in the U.S. South, it's a lot of minority communities that will be most impacted. The communities that are being hit hardest, that then have the least resources to deal with, you know, climate hazards, climate disasters, are those communities of color, and it really does become an environmental justice issue. One of the other big findings that we had in this work was different approaches of how locations are planning for sea level rise in terms of ranges or single estimates. In the U.S. Northeast, as well as the U.S. West, we tended, most of the time, I'd say at least 75% of the time or more, to see a low estimate, a central estimate, and a high estimate, to really capture that full range. Whereas, in the U.S. South, it was much more common to see a single estimate of sea level rise provided, rather than a complete range.

Many cities and states — including Savannah, Georgia, shown above — aren’t planning for the most severe sea level rise scenarios projected by the IPCC. Several, particularly in the U.S. South, also include only a single estimate instead of a range, or don’t forecast beyond the year 2100. (Photo: Jasperdo, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Those places that you mentioned also fall along the political divide in this country. Pretty much, the blue states were providing a range, and the red states were simply providing the simple number. What relation, if any, is there to politics, do you think, with this?

GARNER: Yeah, that's a really good question. It's not one that we fully got to investigate. I should also, you know, caution that it's not 100% in any of those regions, you know, that not all Northeast states have a range, not all Southern states use just one projection. But it is kind of most common to see that divide happening, as you mentioned, along the political divide in the country as well. I think that's a really interesting question to pursue further and perhaps see if it's possible to discern what kind of impact politics really are having on sea level projections, or to quantify that. It's just kind of an unfortunate reality that, you know, scientific fact related to climate change is far too often politicized, not just in this country, but in many countries. And so it's, I think, reasonable to expect that that could be having some influence there.

CURWOOD: Now, some of your data shows that there were some cities that matched or even went further than the IPCC estimates. I believe those include San Francisco and Charleston, South Carolina. What do these examples offer in terms of hope for improving other local projections, do you think?

GARNER: Yeah, I think that's a really important point. You know, it's very easy to look at this study and see, oh my goodness, over half of the locations in the U.S. aren't planning for sea level rise appropriately. But there is that line of hope, where we do see other locations, like you mentioned -- San Francisco, Charleston, South Carolina, some locations in Florida, other locations in the Northeast and places like Oregon -- that do have those reports that are doing a better job of, like you said, either keeping pace and being very close to the amounts of that higher-end sea level rise projected by the latest IPCC report, or even making projections that kind of exceed that higher amount from the IPCC report.

CURWOOD: Related to your study, but not a part of your study, has been the difficulty that people have in framing flood zone territories, because they're based on so-called 100-year floods, which are based really on history. But things are changing. Our understanding of what sea level rise is going to do keeps changing, and there's a lot of variability in it. How do local and statewide decision makers deal with something that really is a moving target for them?

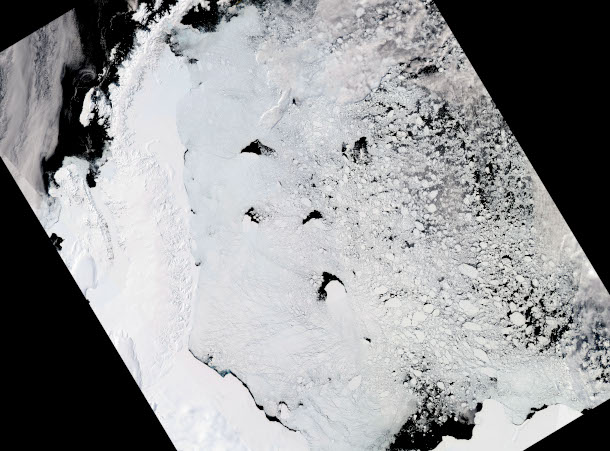

Still, some local assessments matched or went beyond the IPCC’s regional sea level scenarios; some of those places, like New York City, issued reports that considered the potential for particularly severe Antarctic melt. Above, an aerial view of icebergs off the Antarctic Peninsula. (Photo: NASA Earth Observatory, Public Domain)

GARNER: Yeah, and that's one of the really big challenges. And I think that, you know, when we're writing policy, we want that policy to be relatively certain, and it's very common for decision makers to just want to know where the line is drawn, to have that number to put in a document that says, this is how much sea level rise we should plan for. The unfortunate thing is that sea level rise really is just inherently uncertain. You know, we have uncertainty related to things like how Antarctica will melt, but also related to things like how will human emissions of carbon dioxide evolve in the future? Because if we emit less, then we'll see less sea level rise. But if we emit more, we definitely see more sea level rise. So there's, there's just inherent uncertainty in this problem, which makes it difficult to deal with. The good news is that there is a lot of information available to local decision makers to kind of estimate their local sea level rise, you know, whether that's information from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration sea level report, or the IPCC, or even, you know, within the academic literature, there have been several open-access papers published looking at local sea level rise around the world. As you mentioned, it's a moving target, which makes it especially difficult to try to deal with, and I think, you know, maybe to some extent we also just need to develop the frameworks to allow us to have that flexible ability to adapt our policies as we see changes happening.

CURWOOD: Andra Garner is an assistant professor of Environmental Science at Rowan University. Andra, thanks so much for taking time to speak with us today.

GARNER: Yeah, thank you very much for having me. It's been great.

Links

Read Andra’s paper in Earth’s Future

Check out Charlie Miller’s Inside Climate News story about the paper

Explore the IPCC’s projections of regional sea level rise in an interactive map produced by NASA

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth