July 21, 2023

Air Date: July 21, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

A Call to Cool the Earth

View the page for this story

Earth is choked by too much carbon in the atmosphere and running a fever that is only bound to get worse if we fail to restore its balance. Biologist Dr. George Woodwell explains to Host Steve Curwood why soaking up some of that carbon with the help of trees and plants is vitally important to life on Earth as we know it. (08:58)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to discuss the threatened UPS driver strike and how extreme heat is making conditions inside UPS trucks unbearable. They also cover the “greenhushing” some companies are engaging in. And in history, they look back to when a patent was granted for center-pivot agriculture, making the desert bloom with huge green circles of crops. (04:16)

Finance and Climate Denial

View the page for this story

The financial sector isn’t taking likely climate impacts like moderate sea level rise into account when it calculates risks to assets, according to a report. That leaves retirement accounts and pensions vulnerable in a warming world. Inside Climate News reporter Dan Gearino joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain the findings. (08:21)

California Targets Bogus Climate Offsets

/ Aaron CantuView the page for this story

The California legislature is considering measures that would require large businesses to publicly disclose carbon emissions and verify claimed offsets. Aaron Cantu is a reporter for Capital and Main and joined Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to give an overview of the bills and how advocates say they could help California meet its ambitious climate goals. (09:29)

Lowballing Sea Level Rise

View the page for this story

Many U.S. states and cities are underestimating how much the seas could rise even as they plan long term infrastructure, according to a study. Lead author Andra Garner of Rowan University joins Host Steve Curwood to explain why the moving target of climate impacts is confounding some planners. (09:04)

Midnight in the Everglades

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

Alligators have such gaping jaws you might wonder what they eat. For one group of researchers looking into this, the answers so far point to snails and amphibians like the giant salamanders known as amphiumas, rather than fish or hapless mammals that walk too close to swampy waters. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman spent a night in Florida’s Everglades with a team investigating this and shares his story. (07:33)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230721 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Aaron Cantu, Andra Garner, Dan Gearino, George Woodwell

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

California debates cracking down on junk carbon offsets.

CANTU: There's a lot of misinformation in the carbon offset market right now, so this is a way to enforce some of these disclosure requirements so that people can feel confident that these offsets actually really stand for something and aren't just another form of greenwashing.

CURWOOD: And as the climate gets hotter and hotter, the financial sector lowballs the risks.

GEARINO: What if, ten years from now, there are global economic events that are harmful to vast swaths of the economy? Then that means that that's something that my 401(k) is not taking into account.

CURWOOD: Those stories and why we must save the Arctic, this week on Living on Earth – stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

A Call to Cool the Earth

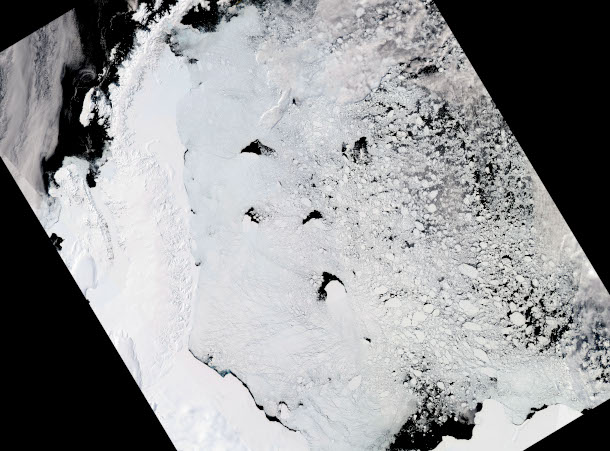

The Arctic plays a critical role in the Earth’s climate system by reflecting heat back into the atmosphere and sequestering carbon in its frozen tundra. (Photo: Duncan Cumming, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Along with record-breaking heat around the world this July, it can be hard to breathe at times in the U.S., thanks to thick smoke from wildfires in Canada linked to global warming. And it’s a reminder of the basic science that the Earth itself breathes. Most of our planet’s landmass is in the Northern Hemisphere, and when the leaves take in carbon in our spring and summer, they leave roughly 600 gigatons of carbon in the atmosphere. And when the leaves fall and release carbon, they bring the total to about 700 gigatons. That atmospheric carbon regulates surface temperatures, and for millennia until the industrial age, temperatures and atmospheric carbon stayed in balance, as trees breathed the carbon in and out.

CURWOOD: But since we started cutting down whole forests and burning massive amounts of fossil vegetation in the form of oil, coal, and gas, we have thrown atmospheric carbon out of balance, and without enough trees, the planet itself is now choking on the excess. One symptom is the fever we call global warming, and this July has been the hottest ever.

CBS NEWSCASTER 1: Temperatures are expected to climb into the triple digits as a heatwave bakes the lower half of the country. Heat advisories are in effect from California through Florida.

CBS NEWSCASTER 2: We're at 12 straight days of temperatures of at least 110 degrees. And that could turn into 13 days. We'll have to see.

CURWOOD: And in Europe.

BBC NEWSCASTER: This heatwave has been named Cerberus. This is a three-headed monster that features in Dante's Inferno, and it's a very powerful heatwave that could cause temperatures to reach 48.8 degrees Celsius, and that could break a record for the hottest temperature ever to be recorded in Europe.

A recipient of many prestigious accolades from the Volvo Environment Prize to the Heinz Award, Dr. George Woodwell has fought to integrate scientific knowledge into public policy for over sixty years and served as a climate advisor in the Carter White House. He also played an influential role in drafting the UN Convention Framework on Climate Change Kyoto Protocol, and helped found the Environmental Defense Fund, and the Natural Resources Defense Fund. George Woodwell also founded the Woods Hole Research Center, renamed upon his retirement as the Woodwell Climate Research Center. (Photo: Daniel Webb)

CURWOOD: China has also broken heat records.

O’NEILL: And a warmer atmosphere is also able to hold more moisture before it precipitates out, as we have also seen this year.

MSNBC NEWSCASTER: Parts of Vermont experiencing their worst flooding since 1927. Worse than Hurricane Irene. Rescue teams worked overnight to find people stranded on streets that have been transformed into rivers.

PBS NEWSHOUR NEWSCASTER: In Northern India, officials say severe flooding from record monsoon rains killed more than 100 people in the last two weeks. In the capital, floodwater blocked roads, closed schools and swept away houses. The destruction left people struggling to cope.

O’NEILL: Because of lag times, today’s climate chaos is not a new normal. Climate disruption will continue to strengthen for years, even after we stop emitting carbon and cutting down trees, but we can limit how much worse it gets. The Paris Climate Agreement called for us to limit average global warming to 1.5 degrees centigrade. But already, according to the World Meteorological Organization, a fifth of the world’s population is experiencing at least one season over 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming, and the whole planet is not far behind.

Extreme weather is accelerating across the globe—and cooling the earth is more urgent than ever. (Photo: Russ Allison Lora, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, practically speaking, what’s to be done? One of the preeminent scientists who, early on, told us about how the whole world’s temperatures are linked to life on our planet is biologist George Woodwell, now in his nineties. Dr. Woodwell was a climate advisor to President Carter, helped start the Environmental Defense Fund and the Natural Resources Defense Council, and created the Woods Hole Research Center, which since his retirement is now called the Woodwell Climate Research Center. For years he warned that if we don’t save the trees and limit emissions, we could set off a feedback loop of global warming that would tap the huge amount of carbon stored in the Arctic’s permafrost. So, finding ways to cool the Arctic might help us while we finally take strong enough climate action. But how? We called Dr. Woodwell in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, to hear his insights and observations. Welcome back to Living on Earth.

WOODWELL: Well, thank you. It's a pleasure to talk with you, always.

CURWOOD: Why is the Arctic so important when it comes to managing climate disruption?

WOODWELL: The Arctic, of course, is a large area mostly covered by tundra, tundra plants, deep peat, organic matter, which have accumulated there for thousands of years. So it's a volume of carbon that's as large as the rest of the carbon held in forests and elsewhere in plants on Earth. An enormous pile of carbon, all vulnerable to decay, vulnerable to being turned into carbon dioxide and methane, warming the Earth.

CURWOOD: So the Arctic is warming nearly four times as fast as the rest of the planet. So, what will happen to the Earth's climate system if the Arctic continues to melt down this way?

WOODWELL: The Arctic is melting, and it's melting with, unfortunately, accelerating rapidity. Partly because the melting feeds on itself. The melting starts a pond. The pond is a black body, and it absorbs more heat, which causes more melting. As one pond is opened up, it quickly forms two ponds or a larger pond, and a big hole. And big pieces of organic matter, 10, 15, 20, 50, or a hundred feet long, and 15 or 50 feet wide, fall into the hole. Big chunks of carbonate fall away. And the products of the procedure are carbon dioxide and methane, largely. So, it's a feedback system. If we destroy or disturb the Arctic, it responds by producing more carbon, which destroys more of the Arctic.

Dr. Woodwell says we could stabilize global temperatures by protecting and establishing vegetation globally, which sequesters a substantial portion of the world’s carbon. (Photo: Mika Hiironniemi, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So sometimes, you've said we need to refreeze the Arctic. How do we do that?

WOODWELL: So, I have been arguing that the only spoken objective of all of these organizations looking at the Arctic, and looking at the climate problem, has to be how we cool the Earth. And we cool it of course, by reducing the amount of heat-trapping gas in the atmosphere. The heat-trapping gases are carbon dioxide and methane, largely. The carbon in the atmosphere has come largely, not only, of course, from our activities, our production of carbon dioxide. Fossil fuels is one, but also from our destruction of forests on a global basis. Forests destroyed, burned, produce carbon dioxide, and to some extent, methane, even though it's aerobic. The problem really is a balance between the Arctic and the rest of the carbon held on Earth, most of it in the vegetation of the Earth, south of the Arctic. The rest of the Earth contains about as much carbon as the Arctic itself. And that pool of carbon can be increased. We can build up the carbon storage, for instance, in forests, globally, which is substantial, and balance it off against the carbon accumulation in the atmosphere that is melting the Arctic. We have to reestablish forests where they've been diminished or abandoned. And we have to build stores of carbon in soils and plants, globally. So the vegetation of the Earth is of critical importance now. That's a fair mission. It's already the mission of many organizations, and most governments in some form, but the intensity with which we go at that topic has to be doubled and redoubled beyond that. It has to be the business of the world to restore the human habitat and the stability of that habitat.

CURWOOD: Now, there are some schemes kicking around to try to blow more moisture over the Arctic to get more Arctic sea ice and everything. What do you think of those schemes?

WOODWELL: Oh, I think it's essential that we restore the sea ice if we can. Restoring the ice and the ice in the Arctic Ocean turns the Arctic Ocean from a black body in summer, absorbing heat from the sun and warming itself further, to a reflective white body of ice, which reflects that heat back into space. Hard to say how to make ice in the Arctic if it doesn't make itself. We don't have an easy mechanism. But it's all a part of the transition toward a stable Earth. And it's our business, without any question.

CURWOOD: George Woodwell is the founder of the Woods Hole Research Center, now known these days as the Woodwell Climate Research Center, in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Dr. Woodwell, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

WOODWELL: Delighted to talk with you.

Related links:

- Woodwell Climate Research Center | “Home Page”

- Woodwell Climate Research Center | “Dr. George Woodwell”

- Volvo Environmental Prize | "2001 Laureate: George M. Woodwell ]”

- The Heinz Awards | "George Woodwell”

[MUSIC: Kruger Brothers, “Up 18 North” on Up 18 North, Double Time Records]

Beyond the Headlines

UPS drivers are threatening to strike if the Teamsters union cannot strike a deal with the company by July 31. One reason for the impending strike is unsuitably hot working conditions. (Photo: Mike Mozart, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: It's time now for a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra, our Living on Earth contributor. Peter joins us from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey, Peter, how are you doing down there in that Georgia heat?

DYKSTRA: It's a really, really hot week, Aynsley. The forecast is from 95 to 100 degrees, unless you're a UPS driver, when the back of your truck can be 130 degrees. That was an issue in the potential strike at the end of the month by the Teamsters union, which represents UPS drivers. I have this great UPS driver that comes through every weekday named Mike, and he tells me it's sweltering back there. That was an issue that actually got tentatively resolved between the Teamsters and the company. But if the strike goes through over pay issues, then nothing is resolved and you'll have a lot of sweaty, suffering UPS drivers in this warmer, warmer weather.

O'NEILL: Yeah, hopefully they can find some sort of resolution that leads to better pay and better AC.

DYKSTRA: And getting my packages would be nice, too.

O'NEILL: And, Peter, what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, a lot of folks who listen to this program are familiar with the concept of greenwashing. It's been around for decades. It's the effort of big companies to tell us all that they're not messing up the environment, somebody else is. Now there's an opposite of greenwashing. You want to know what that is?

“Greenhushing” is when a company chooses to hide its environmental goals and commitments to avoid public backlash. (Photo: Pixabay, CC0)

O'NEILL: I don't know, Peter, what are you talking about?

DYKSTRA: The opposite of greenwashing is “greenhushing.” And that's something that's come about because there are some major companies that may be trying to actually do something about their carbon output, or their use of plastic, but they want to keep quiet about it instead of spending millions to brag about it. They've taken their good works off their website, maybe bragged a little bit less about it in commercials.

O'NEILL: All right, so they're doing good works in secret, sounds pretty good to me.

DYKSTRA: It also sounds pretty counterintuitive after decades and decades of greenwashing. But the issue here is that some major companies are afraid to brag about their environmental virtue, because they're afraid they'll be slapped by the same right-wing organizations that have taken Budweiser to task because Bud Light had the temerity to do a campaign with a trans activist. And those major companies think the same thing will happen if they somehow diss fossil fuels.

O'NEILL: All right, then, Peter, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

Center pivot irrigation creates circular fields of crops. Center-pivot irrigation systems revolutionized agriculture around the world by making marginal farmland more productive. (Photo: NASA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: July 22, 1952, Frank Zybach is awarded a U.S. patent, patent number 2,604,359, for what was called a self-propelled sprinkling irrigating apparatus. Now, in plainer English, that's known as center-pivot agriculture. In mid-America, if you're up in the air, and you look down, you will see these huge circular farm fields being irrigated by a moving hose. And they've changed the face of agriculture, not only in America, but around the world, because marginal land, land that doesn't get enough water, is now in wide use. One of the other things it's doing is draining aquifers, like the Ogallala aquifer that covers most of the middle of the United States and is running dangerously low. So, the good news for agriculture is bad news for the environment. And once again, we have a conflict that started out by an ingenious and well-intended invention.

O'NEILL: All right, well, thank you for bringing us these stories, Peter. Peter Dykstra is a Living on Earth contributor. Thanks again, and we'll talk to you soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Aynsley. Thanks a lot, talk to you soon.

O'NEILL: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- NPR | “UPS Workers Facing Extreme Heat Win A Deal To Get Air Conditioning In New Trucks”

- Washington Post | “‘Greenhushing’: Why Some Companies Quietly Hide Their Climate Pledges”

- Wired | “July 22, 1952: Genuine Crop-Circle Maker Patented”

[MUSIC: Kruger Brothers, “Up 18 North” on Up 18 North, Double Time Records]

CURWOOD: Just ahead, many layers of society, from finance to city planners, are in denial about a hotter future. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Kruger Brothers, “Up 18 North” on Up 18 North, Double Time Records]

Finance and Climate Denial

A new report from the U.K. finds that the financial sector often underestimates the potential economic harm that climate change could cause. (Photo: Josh Appel, Unsplash, Unsplash License)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

As the planet continues to warm, there are numerous consequences for everything from Arctic permafrost to coastal real estate. But a report from the University of Exeter and the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries in the U.K. finds that the financial sector isn’t taking likely climate impacts into account. For example, one model looked at global GDP losses in a world of disastrous 3 degrees Celsius warming, which is double what scientists say is probably manageable for human civilization. But that model did not even include “impacts related to extreme weather, sea level rise or wider societal impacts from migration or conflict.” And that could make accurate financial planning difficult, if not impossible. Here to tell us more about these findings is Dan Gearino, who covers clean energy for our media partner Inside Climate News. Welcome to Living on Earth, Dan!

GEARINO: Good to be here.

O'NEILL: First, let's talk about some of the main takeaways here. What are the authors arguing in their report?

GEARINO: They're saying that a big problem exists with our ability to model the financial effects of climate change. Not only our ability to model this and our ability to make estimates, but also the willingness of financial firms to actually do something with that information and to seek out accurate information. A big part of that is how you account for climate tipping points, you know, these moments where things just leap in terms of their significance, both financially and environmentally. To read this report, you've got this entire array of financial institutions that are just not ready for what's ahead. And therefore, the people that they serve are maybe not feeling a sense of urgency to do something about climate change, because of this.

The report’s authors say the economic models used to forecast risk are ill-suited for investigating the effects of climate change on the financial system. (Photo: Nicholas Cappello, Unsplash, Unsplash License)

O'NEILL: And what do the authors of this report say about why these underestimates might be happening?

GEARINO: So, a big problem is economic modeling itself, this idea of taking variables, taking data we have based on past performance, and estimating what's going to happen in the future. The ways in which some economic models were produced in the past are not super useful for dealing with something like climate change. Just the act of quantifying things is really difficult when you're dealing with unprecedented circumstances.

O'NEILL: And now, you mentioned some tipping points. Are there specific tipping points that people are pointing to that might be affecting the financial sector?

GEARINO: Tipping points can be good and bad. You can reach tipping points where things get significantly better or significantly worse. But when we talk about financial risk, we're mainly talking about those downside tipping points, like massive crop failures. And when we talk purely in terms of climate tipping points, it's this idea of, once we reach a certain point, the negative effects increase substantially. And this has an effect across the economy, but then, kind of figuring out what that effect specifically is going to be is really challenging. You don't want to just throw your hands up and say, 'Oh, we don't know, it's probably going to be really bad.' You know, it's like, that's not super useful. What this report is saying is that, when faced with this challenging set of questions, the people who manage these firms and the people who produce economic models have erred on the side of underestimating the harm.

Economic models, the authors say, often leave out major climate hazards like sea level rise. (Photo: Chris Amelung, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: We've been talking about the financial sector and their underestimations. But what does underestimating the cost of climate change mean for the average person in their day to day lives?

GEARINO: A good example is retirement funds. So, you look at, like, your 401(k). Most 401(k) programs will give you an estimate of how much your expected income will be at a certain age based on modeling software, essentially. They basically are saying that, using their investment approach and using past performance, this is where you can expect to be when you're 65 years old. But what if 10 years from now, there are global economic events that are harmful to vast swaths of the economy? Then that means that that's something that my 401(k) is not taking into account. It's the potential for climate change-related economic harm to substantially increase, almost with each passing year, is something that is not accounted for.

O'NEILL: And in your reporting, you spoke with an economist at Columbia University who wasn't involved in the report that you're reporting on as a whole. And they mentioned that some experts have been warning about the financial risks of climate change for a pretty long time at this point. So, why aren't those concerns more front-and-center in the finance industry? Why hasn't it been changed already?

GEARINO: So, you're talking about Gernot Wagner, who is an economist at Columbia, and I asked him about this report. And one of the things he said is, 'Well, yeah, I've been talking about this for decades, and there are other economists who have been talking about this for a long time.' So, it's not that financial firms haven't been hearing this. But it's almost a question of, kind of, who do you choose to listen to, and how much weight do you put on the various information inputs you're getting if you're a financial firm? So, I think if you're an economist who's been talking about the financial risk of climate change for a long time, it can be frustrating to hear this being talked about as if it's a new idea, because it's not a new idea. What's new is the volume is really being turned up. It's like the, kind of, the level of emergency is higher than it was before.

The authors argue that financial firms should evaluate the risk of future scenarios that involve a “cascading” set of hazards —from extreme weather to food shortages, for instance. Above, drought parches a field in Texas. (Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Public Domain)

O'NEILL: So, where do we go from here? We just work on fixing up those models and we're off to the races, or what are the next steps?

GEARINO: So, in the short term, this organization that issued this report, like, they would like pension funds in the U.K. to use better models. So they're trying to kind of move the needle locally, to make it so that those who really downplay climate risks and are relying on models that have low estimates for climate risk, that those can kind of be pushed aside in favor of models that are going to give more credence to the idea of tipping points, potentially, increasing financial risks substantially. But there's a larger issue, which is just the whole global financial system, you know, and this need to estimate what climate change might do to all of the assets, all the major assets we have, whether it be our retirement funds, whether it be our houses, whether it be, you know, just about anything. I think that this report from the U.K. is a good opportunity to talk about that larger set of concerns.

O'NEILL: Well, so yes, the report is from the U.K. What are you seeing more globally on this front, you know, in the U.S. and elsewhere?

GEARINO: There are a variety of attempts to require companies to disclose the climate risks. There are attempts to do that at the state level, there's attempts to do that through financial regulators. Disclosing your climate risks is only part of the challenge. You also need to make sure those disclosures are accurate and are based on reliable information. But there are versions of this same discussion happening in the United States. And you're seeing more of this in states that have been more, kind of, ahead of the curve in dealing with climate change. It's ultimately, though, something that, you know, any shareholder should be concerned about. I think you're going to see this increasing kind of volume, kind of just turning the volume up on this discussion and trying to make it so that we have a better idea of what, you know, what the future might look like. What that means, though, I mean, that's going to be a frustrating level of uncertainty because you have this wide variety of outcomes. We don't know which one we're going to get. And a lot of that depends on actions that we're taking right now, in terms of policy, in terms of reducing emissions, and to truly grasp with that level of uncertainty and just how unsettled a moment we are in right now, it can be frightening, but I think that that's where this conversation needs to head.

O'NEILL: Dan Gearino is a reporter for Inside Climate News. Dan, thanks so much for speaking with us today.

GEARINO: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Read the report from the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries and the University of Exeter

- Inside Climate News | "The Financial Sector Is Failing to Estimate Climate Risk, Say Two Groups in the UK"

- Read more about how climate change could affect the U.S. financial system

[MUSIC: Julian Lage & Chris Eldridge, “Rygar” on Mount Royal, Free Dirt Records]

California Targets Bogus Climate Offsets

The California State Capitol in Sacramento. (Photo: Pirate Rene, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: One of the states that’s ahead of the curve in dealing with the perils of climate change is California, where the legislature is considering measures that would require large businesses to publicly disclose carbon emissions and verify claimed offsets. A recent investigation led by The Guardian found too many offsets used by companies to claim a net-zero carbon impact are more fiction than fact. For example, the probe found 90% of the rainforest offsets certified by Verra, a carbon offset company used by Disney, Shell, and Gucci, are likely “phantom credits” that don’t equal real carbon reductions. Aaron Cantú is a reporter for Capital and Main who has been covering these bills and he spoke with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

DOERING: Now I understand one of these bills in the California legislature has to do with carbon offsets, many of which have been shown to be bogus. So, how might this bill help with accountability there?

CANTÚ: Sure, so in the voluntary carbon offset market, there aren't many disclosure requirements, either for companies selling the offsets or for companies purchasing them and using them to make claims about their efforts to fight the climate crisis. So, this bill, AB 1305, would require companies either selling or buying these offsets to disclose some pretty fundamental information on their websites. You know, for example, details about the claimed carbon reduction, where, if it's planting trees, for example, where are those trees being planted, what efforts are going into ensuring that those trees aren't being destroyed or that they weren't burned up in a wildfire. The goal really is to make these offsets more credible. There was a exposé in The Guardian earlier this year, that looked specifically at one offsets verification body and found something like 90% of carbon offsets that it verifies could be problematic. So I think as far as offsets, I think just the evidence of problems has been overwhelming. And companies that don't comply with those disclosure requirements would actually face penalties from the state of California. I think the penalty is something like $5,000 a day for noncompliance. I think the penalty can't go past half a million dollars. So, this is really just a way to enforce some of these disclosure requirements, so that people can feel confident that these offsets actually really stand for something and aren't just another form of greenwashing.

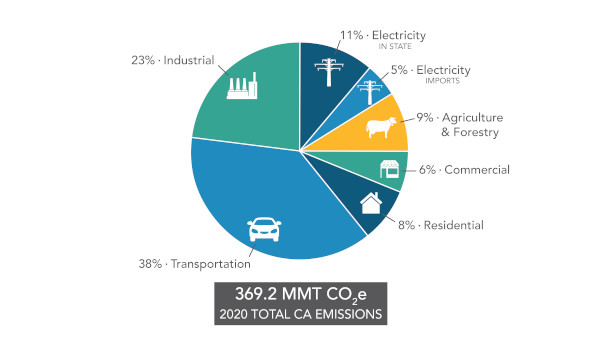

California's greenhouse gas emissions in 2020 broken out by economic sector (Graphic: California Air Resources Board, public domain)

DOERING: And can you walk us through this other California bill in the Senate that would require emissions reporting?

CANTÚ: Sure, so this bill would require companies, large companies that generate over a billion dollars in revenue each year, to disclose all of their emissions across their entire supply chains, to the state of California. This information would be posted publicly, and it would be available for review to anybody who is interested. So, it would have significance for people outside of California as well. Currently, in California, some companies are required to disclose their emissions. These are companies that participate in cap and trade, but this bill would really widen the umbrella to include a lot more companies, basically large corporations. So, you can think, you know, Burger King, for example, or Walmart, Costco, these really big companies that operate in California and you know, as well as other places all over the world, would have to report all of their emissions to the state. And so, this would be valuable information for anybody living anywhere in the world, not just in California.

DOERING: And I understand that this would require Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions to be reported. So that's direct and indirect emissions. Can you explain that a little bit and why that's important?

CANTÚ: Correct. So, Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, these are designations that the United Nations uses to signify different tiers of emissions for companies. And so, kind of the way to think about it is, Scope 1 includes emissions that a business emits, just in the course of its day-to-day activities, you know, if the CEO is driving to work, I mean, that technically counts as an emission. If a company has employees crisscrossing the country in jets, those count as emissions. Basically, any day-to-day activity would count as a company's emissions, that's Scope 1. Scope 2 involves the electricity used by these companies, and it's also kind of related to a business's day-to-day sort of activities. Scope 3 is a little bit different, Scope 3 includes emissions from fuels and other carbon-based products that are burned by consumers, that result in emissions into the atmosphere. And so Scope 3 is especially relevant for oil and gas companies, for example. So, you think about, you know, Chevron is selling gasoline, or jet fuel, so when people burn that fuel that they purchased from Chevron, for example, these would count as Chevron Scope 3 emissions, and Scope 3 emissions actually account for the vast majority of emissions in the atmosphere. And so, that's what's particularly important about this bill, is that it would require these Scope 3 emissions to be reported as well.

According to the National Interagency Fire Center, California leads the country with the most wildfires and number of acres burned. California-specific charts below on the Top 10 largest, most destructive, and deadliest wildfires. (Photo: Cal Fire, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

DOERING: Yeah, I think another example of Scope 3 emissions would be if I go out and you know, it's really hot out right now, I buy a window AC unit, and Scope 3 includes the energy that my air conditioner consumes when I'm running it. So, you can see how, that's a lot of energy, and then there's also, if you factor in the coolant leaking out over time, those are pretty significant emissions.

CANTÚ: Right, exactly. So that's probably the most significant part of this bill, is that it would require those emissions to be reported as well. You know, obviously, companies aren't super happy about that, but those kinds of disclosures and that kind of information is really essential for us to understand what the impact of these companies is on the atmosphere and the contributions they're making to the climate crisis.

DOERING: Now, I can imagine there are companies that are not all that happy about these bills, I mean, to be told the emperor has no clothes and these offsets that you say are real are bogus, you know, that's a little painful for them to swallow. So, how are they responding? What opposition have these bills faced?

CANTÚ: Sure, so the emissions disclosure bill has faced opposition from the California Chamber of Commerce, a very powerful association, obviously, in California as well as in the U.S. Their primary complaint has been that these disclosure requirements would be onerous. One thing that they like to cite is for larger companies that have, you know, contractors and subcontractors within their supply chains, it would be difficult for those smaller contractors to report their emissions. They attempted to pass this bill last year, and that was a complaint that the Chamber of Commerce had, and they've repeated that criticism this year. And for the offset bill, the primary opposition has been the oil and gas industry, the Western States Petroleum Association, which is the largest oil lobbying association in California and the western United States. And the basic complaint that they've had is that this bill creates repetitive and redundant disclosure requirements. I think a key difference is that the California bill, if it becomes law, would impose penalties on companies that do not disclose this essential information. So,whereas right now, it's voluntary, the bill would make it mandatory, and so, yeah, lots of opposition to both of these bills.

According to research led by the Guardian, only six percent of the company Verra’s deforestation credits represented real emissions reductions. Verra is considered the world's leading carbon standard maker for the offsets market and a major source of rainforest offset credits used in the carbon market. (Photo: Axel Fassio, Flickr, CIFOR, CC BY ND 2.0)

DOERING: Now, California is one of the leading states when it comes to setting climate policy, and Governor Gavin Newsom, along with other California legislators, committed to achieving carbon neutrality no later than 2045 and 90% clean energy by 2035. So, where do these two bills on emissions disclosure and carbon offsets fall in the state's climate ambitions?

CANTÚ: Well, if bills were to pass, it would help California reclaim its mantle as a leader on fighting the climate crisis. California has imposed its own deadlines and its own goals for cutting emissions within the state. And other ways, California has led in the past, programs such as cap and trade or the low-carbon fuel standard, another program that was pioneered in California to eventually get fossil fuels out of transportation fuels. These were ideas that California innovated, you know, about 10 or 15 years ago. In recent years, however, other states, other regions, and other countries across the world have also implemented innovative solutions and policies when it comes to fighting the climate crisis, and so, there's been discussion around the fact that, you know, California in some ways isn't really the leader in this space anymore. And that has been the result of the power of the oil and gas lobby in Sacramento, as well as associated business interests. So, I think California really has a lot at stake here. If it doesn't pass these bills, then I don't think California can credibly claim to be the leader in fighting climate change that it likes to present itself as.

CURWOOD: That’s reporter Aaron Cantú from Capital and Main, speaking with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Related links:

- Capital and Main | “Oil and Gas Lobbying Threatens California’s Game-Changing Climate Bills”

- Grist | “A California Bill Could Reveal Corporate America’s Climate Secrets”

- JDSUPRA | “California Senate Passes Broad GHG Emissions Reporting Requirements”

[MUSIC: The Mamas & The Papas “California Dreamin’ – Single Version” on If You Can Believe Your Eyes & Ears, MCA Records]

O’NEILL: Coming up, we travel in the dead of night to Everglades National Park to study the feeding habits of alligators. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Julian Lage & Chris Eldridge, “Rygar” on Mount Royal, Free Dirt Records]

Lowballing Sea Level Rise

More than half of the U.S. cities and states that Andra and her colleagues examined in their study underestimated the upper end of possible sea level rise, compared to forecasts by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (Photo: Wade Austin Ellis, Unsplash, Unsplash License)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Almost a third of the U.S. population lives along the coast, where rising seas are already flooding streets and contaminating groundwater. Because of geography and how heat is distributed in the oceans, sea levels don’t rise equally everywhere. To prepare for the future and protect critical infrastructure, communities need to predict how bad it’ll be along their coastlines. But a study from early 2023 compared these projections to numbers from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and found that many U.S. states and cities are underestimating how much the seas could rise. Here to tell us more about this research is Andra Garner of Rowan University, lead author of the study. Welcome to Living on Earth, Andra!

GARNER: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So, what did you find when you compared the local projections to the IPCC report?

GARNER: One of the big takeaway things that we found was that over half of the locations in the U.S., the local projections were just not quite keeping pace with the higher amounts of sea level rise from the IPCC. And, you know, that could be just that they're not looking at a high enough emissions scenario to match those higher emissions scenarios from the latest IPCC report. Or maybe they're not looking at a full range of the possible future projections. And I think that's one thing that this paper really illustrated, is, you know, everyone has the same information available to them, but how you deal with it and the decisions you make along the way result in different approaches to planning for sea level rise.

Rising seas can erode coasts, send saltwater into aquifers, and worsen flooding. Above, high tide inundates a street in Florida. (Photo: Dave, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: I mean, there's some places -- I'm thinking of Savannah, Georgia, parts of the Mississippi Delta -- that have projections for 2100 that are a meter, or more, lower than the IPCC's. You know, that's like three feet. What's the problem with cities and states underestimating the high end of possible sea level rise? I mean, why is it so important for coastal communities to consider the high end when they plan for the future?

GARNER: If you think about it -- use an analogy. If you were going to go on vacation, and you look up the forecast for where you're going on vacation, and you see that it is supposed to be sunny every single day, you still might want to pack an umbrella in your luggage, because we know forecasts have some uncertainty. That could change, you might get caught in the rain, and you don't want to have to run out and find an umbrella while you're on vacation. Kind of the same idea applies for sea level rise projections. You know, we can look at what's most likely, but when it comes down to planning, and especially when we're thinking about, you know, really critical infrastructure, things like power plants or hospitals, we might want to be taking a more cautious approach than what's most likely. It's going to be even more costly to try to go back and retrofit our infrastructure and try to adapt on the fly than if we had kind of been planning all along for those potentially higher amounts of sea level rise.

CURWOOD: Looking over your data, I noticed that there were no projections of sea level rise offered by communities in the South after the year 2100. You know, a baby born today probably is going to be living past that period of time.

GARNER: Yeah, that was one of the other big takeaways is that, you know, to not have those longer-term sea level projections is concerning, certainly in any location around the country, but in the U.S. South is especially concerning, perhaps, because there have been other studies that have looked at how flooding will change around the country, and have found that, particularly in the U.S. South, it's a lot of minority communities that will be most impacted. The communities that are being hit hardest, that then have the least resources to deal with, you know, climate hazards, climate disasters, are those communities of color, and it really does become an environmental justice issue. One of the other big findings that we had in this work was different approaches of how locations are planning for sea level rise in terms of ranges or single estimates. In the U.S. Northeast, as well as the U.S. West, we tended, most of the time, I'd say at least 75% of the time or more, to see a low estimate, a central estimate, and a high estimate, to really capture that full range. Whereas, in the U.S. South, it was much more common to see a single estimate of sea level rise provided, rather than a complete range.

Many cities and states — including Savannah, Georgia, shown above — aren’t planning for the most severe sea level rise scenarios projected by the IPCC. Several, particularly in the U.S. South, also include only a single estimate instead of a range, or don’t forecast beyond the year 2100. (Photo: Jasperdo, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Those places that you mentioned also fall along the political divide in this country. Pretty much, the blue states were providing a range, and the red states were simply providing the simple number. What relation, if any, is there to politics, do you think, with this?

GARNER: Yeah, that's a really good question. It's not one that we fully got to investigate. I should also, you know, caution that it's not 100% in any of those regions, you know, that not all Northeast states have a range, not all Southern states use just one projection. But it is kind of most common to see that divide happening, as you mentioned, along the political divide in the country as well. I think that's a really interesting question to pursue further and perhaps see if it's possible to discern what kind of impact politics really are having on sea level projections, or to quantify that. It's just kind of an unfortunate reality that, you know, scientific fact related to climate change is far too often politicized, not just in this country, but in many countries. And so it's, I think, reasonable to expect that that could be having some influence there.

CURWOOD: Now, some of your data shows that there were some cities that matched or even went further than the IPCC estimates. I believe those include San Francisco and Charleston, South Carolina. What do these examples offer in terms of hope for improving other local projections, do you think?

GARNER: Yeah, I think that's a really important point. You know, it's very easy to look at this study and see, oh my goodness, over half of the locations in the U.S. aren't planning for sea level rise appropriately. But there is that line of hope, where we do see other locations, like you mentioned -- San Francisco, Charleston, South Carolina, some locations in Florida, other locations in the Northeast and places like Oregon -- that do have those reports that are doing a better job of, like you said, either keeping pace and being very close to the amounts of that higher-end sea level rise projected by the latest IPCC report, or even making projections that kind of exceed that higher amount from the IPCC report.

CURWOOD: Related to your study, but not a part of your study, has been the difficulty that people have in framing flood zone territories, because they're based on so-called 100-year floods, which are based really on history. But things are changing. Our understanding of what sea level rise is going to do keeps changing, and there's a lot of variability in it. How do local and statewide decision makers deal with something that really is a moving target for them?

Still, some local assessments matched or went beyond the IPCC’s regional sea level scenarios; some of those places, like New York City, issued reports that considered the potential for particularly severe Antarctic melt. Above, an aerial view of icebergs off the Antarctic Peninsula. (Photo: NASA Earth Observatory, Public Domain)

GARNER: Yeah, and that's one of the really big challenges. And I think that, you know, when we're writing policy, we want that policy to be relatively certain, and it's very common for decision makers to just want to know where the line is drawn, to have that number to put in a document that says, this is how much sea level rise we should plan for. The unfortunate thing is that sea level rise really is just inherently uncertain. You know, we have uncertainty related to things like how Antarctica will melt, but also related to things like how will human emissions of carbon dioxide evolve in the future? Because if we emit less, then we'll see less sea level rise. But if we emit more, we definitely see more sea level rise. So there's, there's just inherent uncertainty in this problem, which makes it difficult to deal with. The good news is that there is a lot of information available to local decision makers to kind of estimate their local sea level rise, you know, whether that's information from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration sea level report, or the IPCC, or even, you know, within the academic literature, there have been several open-access papers published looking at local sea level rise around the world. As you mentioned, it's a moving target, which makes it especially difficult to try to deal with, and I think, you know, maybe to some extent we also just need to develop the frameworks to allow us to have that flexible ability to adapt our policies as we see changes happening.

CURWOOD: Andra Garner is an assistant professor of Environmental Science at Rowan University. Andra, thanks so much for taking time to speak with us today.

GARNER: Yeah, thank you very much for having me. It's been great.

Related links:

- Read Andra’s paper in Earth’s Future

- Check out Charlie Miller’s Inside Climate News story about the paper

- Explore the IPCC’s projections of regional sea level rise in an interactive map produced by NASA

[MUSIC: Julian Lage & Chris Eldridge, “Lion’s Share” on Mount Royal, Free Dirt Records]

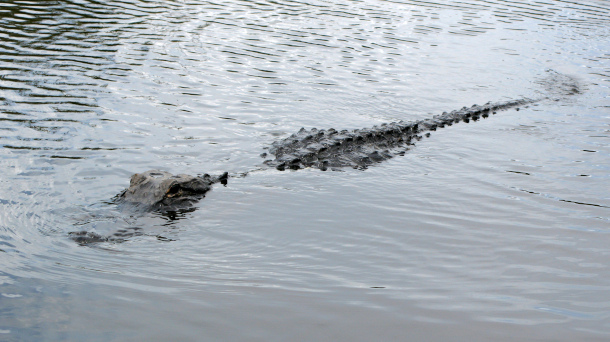

O’NEILL: Alligators have such gaping jaws, you might wonder what they eat. For one group of researchers looking into this, the answers so far point to snails and amphibians like the giant salamanders known as amphiumas, rather than fish or hapless mammals that walk too close to swampy waters. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman spent a night in Florida’s Everglades with a team investigating this.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Distill,” Darby, Blue Dot Sessions 2021]

Midnight in the Everglades

An alligator in Everglades National Park. (Photo: Sheila Sund, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

LYMAN: We ply the darkness in a noisy airboat, my friend Brady in the pilot’s seat, spotlighting for alligators. The flat-hulled craft is made for this environment, and we move easily through thick patches of four-foot-tall sawgrass and shallow water that ranges in depth from a few inches to a few feet. The breeze from the moving boat makes the 70-degree early evening air feel cooler than it actually is.

Brady is a graduate student, studying alligator diets in Everglades National Park for his Ph.D. dissertation. He has spent the past few years catching gators and pumping their stomachs to analyze what they are feeding on — research that could prove important in helping to conserve the iconic reptiles.

"There's one up ahead!" Brady shouts over the roar of the engine. Don, his undergraduate assistant, stands at the bow of the boat holding a gator noose, which consists of a long aluminum pole with a wire noose attached to about 30 feet of rope.

The reptile's eyes glow orange in the beam of the spotlight as it floats motionless in the water ahead. As we get closer it begins to swim away along the surface. Brady explains that alligators spook easily in daylight, quickly diving out of sight, but for some reason, at night, they don't, making them easier to capture, which is why gator researchers often work the graveyard shift.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Flashing Runner,” Resolute, Blue Dot Sessions 2017]

LYMAN: Don steadies himself as Brady maneuvers the boat closer to the swimming animal. He reaches out with the noose and tries to slip the loop of wire over the gator's head, but misses.

"Get him!" Brady barks.

"I'm trying!" Don shoots back.

When we get close, Don tries again, but again, he misses.

“Just get it on him!” Brady yells.

On his third attempt, Don lassoes the gator, which dives underwater with a splash of its thick, powerful tail.

It pulls on the line, occasionally surfacing near the boat, thrashing wildly.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Flashing Runner,” Resolute, Blue Dot Sessions 2017]

LYMAN: After about 10 minutes, the gator begins to tire, and Don slowly pulls the line in. Brady cuts the engine, comes down onto the deck, and lies down on his stomach to be in position to grab the gator, but quickly decides he’s too vulnerable.

“Let me get on my elbows,” he says. “I can’t go anywhere if the gator tries to get me.”

A twelve-foot alligator pokes its head above the surface of the water. (Photo: djmcaleese, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Brady asks me to duct-tape the gator’s jaws shut, so I join him on the deck with a roll of duct-tape, nervously crouching on my knees, my heart pounding. Don maneuvers the line so the gator's head is above water and tight against the bow. Brady grabs the gator's jaws and holds them shut while I duct-tape around the animal’s snout as fast as I can, with Brady yelling, "Hustle! Hustle! Hustle!"

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Flashing Runner,” Resolute, Blue Dot Sessions 2017]

LYMAN: When the duct-taping is through, Brady releases his grip, Don lets up on the line, and the gator disappears beneath the surface in an explosion of water.

After several minutes, Don once again pulls the exhausted animal toward the boat. He and Brady step off the edge of the bow into the knee-deep water and wrestle the big black reptile onto the deck. Don lies on top of the gator with his hand over its eyes to keep it still, while Brady duct-tapes the animal’s feet together behind its back so it can’t move around.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Plaster Combo,” Darby, Blue Dot Sessions 2021]

To pump the gator’s stomach, it has to be filled with water, which is done using a submersible pump attached to a section of garden hose. Brady removes the duct-tape from the gator’s mouth, then gently taps the reptile on the snout with a section of PVC piping. The gator opens its mouth wide and lets out an angry hiss.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Plaster Combo,” Darby, Blue Dot Sessions 2021]

Brady places the pipe lengthwise in the gator’s mouth, which causes it to clamp down hard on the PVC piping. He then wraps duct-tape around the gator’s mouth again, so the plastic pipe won’t fall out.

The pump is placed in the water, the animal is rolled onto its back, and the end of the hose is lubricated and gently inserted down the alligator’s throat through the PVC pipe. Its stomach quickly fills with water when the pump is turned on.

I press down on the reptile’s distended stomach with both hands, like I’m performing CPR, causing the gator to regurgitate its stomach contents into a bucket, which we collect for processing back at the lab. We repeat this routine several times until nothing but water comes out.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Plaster Combo,” Darby, Blue Dot Sessions 2021]

LYMAN: Brady told us one time he was pumping the stomach of a big gator and a live three-foot-long amphiuma — a large, aquatic, eel-like salamander — rocketed out of the gator’s mouth and latched onto Brady’s arm, giving him a painful bite and scaring him half to death.

Fortunately, the gator we captured contained only a few clumps of scales from a water snake it had eaten.

“That’s a pretty Spartan diet,” Brady comments.

After measuring and tagging the animal, we untape its legs, and the 10-foot reptile calmly clambers over the side of the airboat into the water, and slowly swims away along the surface into the darkness.

Over the next several hours, we catch a few more gators and repeat the stomach pumping routine.

Don Lyman (left), Seth Lambiase (center) and Brady Barr (right) grab hold of an alligator on their airboat in Everglades National Park in November 1996. (Photo: Don Cramps, courtesy of Don Lyman)

Brady said that, prior to his study, it was thought alligators in south Florida ate mostly fish, but he had discovered that larger gators fed predominantly on snakes, amphiumas, and surprisingly, apple snails. In fact, snails were the major prey item for sub-adult gators. Brady had found that big gators would occasionally feed on wading birds and mammals, too. His research helped to analyze the complex, interconnected food web that makes up alligators’ diets.

After tagging the last gator, we release it back into the water, then sit for a bit, contemplating the night’s events.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Distill,” Darby, Blue Dot Sessions 2021]

LYMAN: The adrenaline is still pumping as we excitedly recount our adventures.

“Did you see Don jump when that big gator attacked the airboat right under his feet?” Brady says. Excited banter soon gives way to quiet reflection.

“It’s beautiful out here,” I say.

“It sure is,” Brady replies.

Moonlight illuminates our surroundings, and a gentle breeze blows in from the Gulf of Mexico, stirring the sawgrass. A red light blinks from the top of a radio tower in the distance, and lightning briefly flashes in small patches here and there on the horizon. Solitude envelops us.

[OWL SOUNDS]

O’NEILL: That’s Living on Earth’s Don Lyman.

Related links:

- Learn more about Everglades National Park

- Don Lyman’s Twitter

- Learn more about Dr. Brady Barr

[MUSIC: Amphibious Zoo Music “Gator Baiter” on Bayou Blues: Southern Fried Guitar Jams, Amphibious Zoo Entertainment Group]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Swayam Gagneja, Madison Goldberg, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Clare Shanahan, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

O’NEILL: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth