Defending Climate Science

Air Date: Week of May 16, 2025

The American Geophysical Union and the American Meteorological Society are joining forces to keep momentum for climate research in the US despite disruptions to Federal funding and projects. Pictured above is the entrance to the American Geophisical Union’s headquarters in Washington, DC. (Photo: sikeri, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

When the Trump administration dismissed the roughly 400 scientists working on the National Climate Assessment, professional scientist organizations stepped up to coordinate their own collection of the latest climate research. Brandon Jones is President of the American Geophysical Union and joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about the importance of peer-reviewed climate science and clear communication with the public as climate impacts intensify.

Transcript

CURWOOD: One of the steps the Trump administration has taken to undermine climate science throughout the executive branch included the dismissal of the roughly 400 scientists working on the National Climate Assessment. That’s a key government report published every few years on climate risks and impacts, and this decision comes as communities across the U.S. face escalating climate threats, from record wildfires to intensifying hurricanes and rising sea levels. In response to this disruption, the American Geophysical Union and the American Meteorological Society have announced a collaboration to support U.S. climate science, including a new special collection of studies. Joining us to discuss this effort and the broader implications for science in the US is Brandon Jones, President of the 60,000 member American Geophysical Union or AGU. Brandon, welcome to Living on Earth!

JONES: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: The AGU—the American Geophysical Union—and the American Meteorological Society have announced the creation of a special collection for issues on climate change in the US. To what extent are you just trying to rebuild what's been torn down or move forward with yet a new model?

JONES: The National Climate Assessment is a congressionally mandated report, and so Congress and the Federal Government are going to have to figure out what's going to be done for that report itself. And so the special collection that AGU and AMS are coming together to support is not to replace that. You can look at it as there's a crack in the system they've released all these authors and things are going to be stymied or halted. Some may think: Well, someone needs to fill in that crack with that same type of report. But I would say, Well, if the crack gets filled in, are we supporting a system that's already crumbling, or are we trying to hold up a system that just needs to part of it, not the whole thing, fade away, so that something new can show up? And I think the special collection example is where we've seen a crack, and we see the daylight and what's possible on the other side. And instead of trying to replace, we're just going to do something new.

CURWOOD: Tell me, what's the timeline here for the special collections, and who is getting invited to contribute?

Brandon Jones, 2025-2026 AGU President, has served on AGU’s Board since 2017 while spearheading initiatives to expand STEM access and career pathways for early-career researchers. (Photo: Courtesy of Brandon Jones)

JONES: So the timeline right now, since we're in the first phases, where we don't have an actual set time, we're thinking maybe over the next two years or so that we'll have the opening of the special collections for submissions, and it is wide open to the scientific enterprise, and we're also—we being AGU and AMS—are kind of putting out a call to action for other professional societies to come and join this, so the more journals that are involved in this growing library in this special collection, the better, because that way we'll reach a wider swath of our scientific community and have even more extensive data and research to share.

CURWOOD: One of the criteria for people to participate in this is peer-reviewed research. Remind us, for people who maybe don't quite know what peer review is, what is that?

JONES: Peer review, in my opinion, is part of that special sauce that makes scientific method as unique as it is among other sectors. So if you're a scientist and you've analyzed the data that you've collected, you write it up, and then you submit it to other experts in your field or discipline or related disciplines, basically for them to just shred it. The peer reviewers as experts, if they give a thumbs up, what they're saying is that the idea, the concept, the experimentation, the implementation, the analysis, the conclusions drawn, all make sense, and the results that then are coming out of this work can be trusted.

CURWOOD: What do the dismissal of the National Climate Assessment authors tell us about the current challenges of integrating scientific expertise into policy making do you think?

The Trump Administration dismissed all contributors to the National Climate Assessment on April 28th. The NCA is the US government’s comprehensive report on climate change impacts and risks in the US. (Photo: WhiteHouse.gov, Public Domain)

JONES: This, I think, is where not just the general public needs to be more aware of the importance of science and decision making, but scientists themselves, in my opinion, could be encouraged and maybe mobilized to become a bit more active in the political space. Traditionally, speaking out on issues that are of public interest aren't really how scientists are trained, and in some instances, there's activation energy against being too much of an advocate for something, and there's a sense that if you start to weigh in on a particular issue from your scientific expertise, somehow you're diluting the objectivity that makes science an interesting and trusted enterprise. But I would argue that if you're a scientist that receives federal funding, you're already in the political fray, because that funding is coming from a congressionally mandated process, and it's being administered by an administration that was elected and has priorities already in place. But the bigger picture is we're facing existential problems, climate change being one of them, global pandemics, AI and cyber security being another. We need the scientists and we need the data, the verified data, to help decision makers do the best that they can for the citizenry.

CURWOOD: Now, we've seen science misinformation proliferate in recent years. How do you feel this has affected both research efforts and the public trust in scientific institutions?

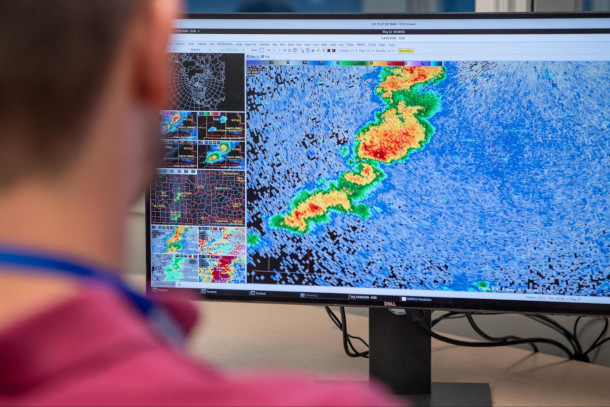

Emergency prediction systems rely on data and scientists. Initiatives like the Watch-to-Warning Experiment aim to enhance severe weather communication by optimizing risk messaging between watches and warnings during evolving storms. (Photo: NOAA NSSL, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

JONES: I will say that, as a former high school educator, there's this coupling of misinformation with general 'unknowing' among much of the citizenry. If I look at the K-12 system—the public education system—the responsibilities and the overload that our teachers and administrators and guidance counselors are under… and I'll say this, just me personally: teaching students to take tests instead of opening up opportunities for learning, and then the content that is being provided… So what—Certainly in the sciences, you have core content in the K-12 system, like chemistry and biology and physics, but you have very little Earth System Science—oceanography, atmospheric science, solid earth science, and environmental science. And so, by the time students graduate high school, and they move into—they go to college or they're off into their careers—the general knowledge about how the earth works just isn't there. And so, once they're into adulthood and their careers, depending on their news environment—in other words, where they get their information from—if they can't filter the information with foundations from their early education or even their college education—where there's trusted information—then people might be swayed by misinformation.

CURWOOD: This also relates to my profession, that is journalism. For many years on the question of the climate, the supervising editors would say, "Well, some people say there's climate disruption, other people say there isn't. Let's split the difference". How does that work in science?

Tornado damage near Putnam County, Tennessee, USA in March 2020. (Photo: Chuck Sutherland, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

JONES: So that example there is interesting, because 97 to 98% of climate scientists around the world agree that the climate is changing due to human activity—and so, if the average citizen is watching a journalistic piece on climate change, and the two talking heads that are on the screen are a climate scientist and a climate denier, that average citizen might think, "Okay, well, this is really a balanced argument—who's to say who's right?" But if I were a producer—and I have no idea about how that happens in your world—I would maybe put 97 climate scientists up and three deniers and then have the debate… and see what the average citizen would think about that.

CURWOOD: Now, how will the American Geophysical Union and the American Meteorological Society ensure that this research actively counters politicized narratives and empowers everyday people?

JONES: Now, that's a great question. I know on the AGU side, I can't speak for AMS, but we have a stellar communications team internally on the staff side, and so as an organization, for decades now, we've engaged with mainstream media. Now we also have a strong social media presence, we're on multiple platforms, but we also have a policy department at AGU that engages with Capitol Hill on both sides of the aisle and also empowers our members through trainings and templates how to be advocates at the local level or even the state level. So there will be multiple ways for this information to reach not only the academic community and the broader research enterprise, but also the general public.

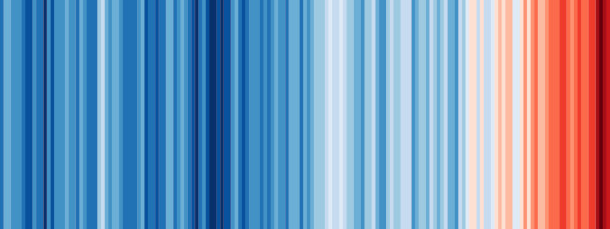

Created by climate scientist Ed Hawkins, the "warming stripes" use a striking gradient of blue-to-red vertical bands to visualize Earth’s rising temperatures since the 19th century. Each stripe represents a year’s average temperature deviation from the long-term norm. (Photo: Ed Hawkins, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: Facing the dismantling of climate science infrastructure and trust, what's at stake if this just continues unchallenged?

JONES: Just to be blunt, lives are at stake. For example, the climate is changing. We know that severe storms are increasing in their intensity and their frequency. So if you have an agency like NOAA, where the National Weather Service is housed, and you have forecasting models for early warning systems. Those models are based on data, and that data is being collected, not only through instrumentation, but also from scientists, but even through the instrumentation. The scientists are the ones that are responsible for ensuring that data is of high quality. If there's a disruption in that flow of information, a removal of scientists or expertise, there are going to be implications on how trusted that forecasting model is, and there's going to be an impact on the early warning systems. So now we're talking about lives, we're talking about economic loss, we're talking about power interruptions, the cascade effects—everyone can imagine those. So that's just an example of what is at stake.

CURWOOD: If the present challenges are met with robust scientific engagement and public collaboration. What kind of future could we build in terms of climate resilience and policy progress do you think?

A protestor holds a sign reading ‘Denied Facts are Still Facts’ during the 2017 People’s Climate March in Washington D.C. (Photo: Edward Kimmel, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

JONES: The future is unlimited, if we can figure out how to come together. Given what's going on, the dismantling of departments and institutions and organizations across the research enterprise, and the firing of employees and all of this disruption—For me, the way to combat that is through coalitions and through cooperation and through collaboration. And I'm beginning to see lots of evidence of that happening in ways, maybe that it wouldn't have happened, or it would have happened in a longer period of time. In a very weird way, and I can't believe I'm saying this, this disruption might have given us the kick in the pants that we needed to move out of our silos and really connect with other sectors, not just in research and science, but even outside, to build the future that we really need.

CURWOOD: Brandon Jones is the president of the American Geophysical Union, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

JONES: Oh, it was my pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

Links

Learn more about the National Climate Assessment (NCA)

Visit the American Geophysical Union (AGU) official site

Visit the American Meteorological Society (AMS) official site

Learn about Brandon Jones’ role and mission as AGU president

Read more about the dismissal of contributors to the National Climate Assessment

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth