May 16, 2025

Air Date: May 16, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Pope Leo and Creation Care

View the page for this story

The new Pope, Leo XIV, has worked with interfaith environmental networks and there’s hope around the world that he may follow in the footsteps of his predecessor Pope Francis and bring issues of the environment and climate change to the forefront of his agenda. Dr. Erin Lothes is a former professor of Catholic theology who now promotes global eco spirituality education and climate action with the Laudato Si’ Movement and she joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to shed light on Pope Leo XIV’s rhetoric on environment. (11:59)

Birdnote®: Toucan - Tropical Icon

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

In the Peruvian Amazon not far from where Pope Leo XIV lived for many years, you can find a most distinctive bird with a comically huge bill. BirdNote’s Mary McCann reports on the toucan, a tropical icon. (02:07)

Autism and Chemicals

View the page for this story

Autism spectrum disorder is now diagnosed in about 1 in 31 children in the United States, a rise of 70 percent in just four years according to the CDC. In addition to better awareness and changing diagnostic tools, growing scientific evidence also points to the role of exposure to toxic chemicals especially during early development in the rising prevalence of autism. Dr. Philip Landrigan, a pediatrician, professor at Boston College, and one of the world’s leading experts on toxic exposure from plastics and pollution discusses with Host Steve Curwood. (11:35)

"Countermeasures"- Dunlin

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

On the placid saltpans of Parker River National Wildlife Refuge in coastal Massachusetts, the shorebirds known as dunlin are feeding. Then, just like that, they rise and fly in almost perfect unison to evade an intruder, Living on Earth’s Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender reports. (02:43)

Oystercatchers Bounce Back

View the page for this story

The American oystercatcher is a conservation success story thanks in part to efforts to educate the public and protect their ground nests from unaware beachgoers. Host Aynsley O’Neill shares with Host Steve Curwood the story of how conservationists worked together to boost the numbers of this charismatic species. (07:30)

Defending Climate Science

View the page for this story

When the Trump administration dismissed the roughly 400 scientists working on the National Climate Assessment, professional scientist organizations stepped up to coordinate their own collection of the latest climate research. Brandon Jones is President of the American Geophysical Union and joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about the importance of peer-reviewed climate science and clear communication with the public as climate impacts intensify. (11:44)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

250516 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Jon Hurdle, Brandon Jones, Philip Landrigan, Erin Lothes, Shiloh Schulte

REPORTERS: Mark Seth Lender, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

The new Pope has spoken out against the destruction of nature.

LOTHES: He said that there must be a relationship of reciprocity with the environment of mutual care, so that is a beautiful recognition that we depend on the environment for all our sustenance, and today the environment needs us to do our part and care for it.

CURWOOD: Also, a shorebird bounces back.

SCHULTE: When I moved to Maine, there were no oyster catchers near me, and now there's a pair nesting just a few miles from my house along the beach or along the coast. And so I can go down there and I can see these oyster catchers that are here now because of the work of the, of this group that I've been part of, for the last couple of decades. And so it's really gratifying, it's really exciting to see.

CURWOOD: We’ll have those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Pope Leo and Creation Care

Pope Leo XIV (center), the first US born pontiff, addresses the crowd from the balcony of St. Peter's Basilica. Behind him are a member of the Catholic clergy (left) and Archbishop Diego Giovanni Ravelli (right). (Photo: Catholic Church of England, Flickr, CC BY NC ND 2.0)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

The new Pope could guide the Catholic Church into a new era of care for the environment. Pope Leo XIV, once known as Robert Prevost, previously served as a bishop in Chiclayo, Peru, a city not far from the Amazon rainforest. And according to the Associated Press, “Prevost deepened his ties with interfaith environmental networks like the Interfaith Rainforest Initiative and Indigenous organizations” which place “forest protection and rights at the center of Church concern.” He was also the president of the Pontifical Commission for Latin America, which connected him with neighboring countries that are also home to the Amazon. So there’s hope around the world that the new Pope may follow in the footsteps of his predecessor Pope Francis and bring issues of the environment and climate change to the forefront of his agenda. Dr. Erin Lothes is a former professor of Catholic theology who now promotes global eco spirituality education and climate action with the Laudato Si’ Movement, named for Pope Francis’ ecological encyclical. And she joins us now to shed more light on Pope Leo XIV. Erin, welcome to Living on Earth!

LOTHES: Thank you so much, Aynsley. I am delighted to be with you.

O'NEILL: What have we heard so far from Pope Leo about the environment?

LOTHES: When Robert Francis Prevost was still Cardinal in 2024 he attended a conference in Rome on the environmental crisis, and in his remarks, he stressed that it's time to move from words to action, and that we must find our guidance from Catholic social teaching, which includes Rerum Novarum from 1891 all the way up to Laudato Si and Laudato Deum. And he further said that dominion over nature should not become tyrannical. So a critique of this commonly heard critique that we are stewards, we have dominion. No, this is a false interpretation of the Bible, and it's been denounced by Pope Francis and by countless theologians. He further said that there must be a relationship of reciprocity with the environment of mutual care. So that is that beautiful recognition that we depend on the environment for all our sustenance, and today, the environment needs us to do our part and care for it. Likewise, he cautioned against the harmful consequences of technological development and this is a clear pillar of Catholic teaching about the environment. Technology is a blessing. The products of human ingenuity and engineering are a gift that makes life easier, healthier, safer, more dignified, yet technology can go out of control. We can have technologies with harmful impacts. And so just because something is new, that doesn't mean it's progress. We need to ethically and culturally evaluate every new technology and see if it brings about the common good. And so he emphasized how Vatican City has committed to protecting the environment, like installing solar panels and shifting to electric vehicles. So those are some of his clear public on the record statements about the environment.

Pictured above is Pope Leo the XIV, formerly known as Robert Prevost. (Photo: Edgar Beltran, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 2.0)

O'NEILL: And from what I've read so far, it seems like he aligns with Pope Francis on a few key issues. What are his sort of marching orders as he inherits Pope Francis's legacy? And of course, what part of that portfolio is the climate emergency?

LOTHES: Listening to others, I think is one of his top agendas. As you say, his marching orders for Pope Francis. Pope Francis opened up the entire church to a listening process, which is also such a new moment in the church. This was called the synodal process, which means walking together the Synod. And he invited every single Catholic in every parish around the world to meet together, to listen to each other in round table discussion, to take notes and pass that up to the bishop, to pass that up to the national Bishops Conference, to pass that up to Rome. It's this unthinkable gathering of the thoughts and hopes and dreams of the ordinary Catholic to share what's so precious about their faith. So this whole synodal process has been going on for years, and really from his dying days, Pope Francis called for the Synod to continue. And in his opening message from the balcony in Rome, Pope Leo the 14th said "let us walk together" and that is a very clear reference to the ongoing desire to continue this listening process, this common, shared, humble listening process.

O'NEILL: And he chose the name Leo. Why is that? And for that matter, what was Pope Leo XIII known for?

LOTHES: It's so significant. As soon as we all heard the name Leo the XIV, so many values and images left into mind. It's just as when Jorge Maria Bergoglio chose the name Francis, everybody caught their breath. Oh, my goodness, Francis. There was never a Francis never, ever in 2,013 years. And we know what it meant, right? St. Francis is the patron of ecology. He was this humble radical man who called the wolf his brother and the water his sister. So it was almost shocking. And when we hear Leo the XIII, he is most known for his teaching letter, his encyclical Rerum Novarum, which means on new things, or maybe on revolutionary change, because writing in 1891 Pope Leo was aware of the suffering of urban poverty, of the needs of workers, of the crises that came with factories and smoke stacks and child labor and the struggle for fair wages and the needs for workers to have representation vis a vis the owners of factories, etc., and he advocated for them to be able to care for their needs. So this document is recognized as the foundation of modern Catholic social teaching. So for Cardinal Prevost to choose the name Leo the XIV, he's saying that he will continue this concern for the poor in a new situation, in the poverty and in the crises of today, this concern for the poor, especially for new crises and critiques of the excesses of hyper neoliberal capitalism, are implied in this name.

Santa Maria Cathedral in Chiclayo, Peru. Santa Maria is part of the Diocese of Chiclayo, where Robert Prevost served as bishop from 2015 to 2023. (Photo: Frank Coronel Mendoza, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 4.0)

O'NEILL: What would you say is the influence or the role that a pope takes in times of emergency, like the climate crisis that we're facing right now?

LOTHES: There is a lot of influence that a pope can have. Many see the pope as a most visible moral authority, given that he is the one single leader of a very, very large religious community. And so for one thing, he has the world's biggest pulpit. He has the greatest capacity to preach care of creation to the world. He has the ability to engage all the bishops of the world, which embrace a population of 1.4 billion Catholics. That's on the practical level. The pope can also speak to the political and diplomatic community, as Pope Francis did attending global conferences, coming to speak to the Congress of the United States, as he did, he hoped to attend the last COP, unfortunately he was not well, but those are the things they can do. And by issuing Laudato Si right before the Paris conference, he deliberately and effectively influenced the outcome of that historic gathering. Pope Francis engaged with the heads of oil corporations. He invited them to his office and had a meeting with the executives of fossil fuel companies. This is an astonishing direct engagement, and that's something that very few groups can do in a moral sense. So there's a lot of influence that the Pope has, and as an American, Pope Leo the 14th will have an even more intense capacity to engage successfully from within our culture, as someone who not only understands it, but lives it and can't be dismissed as someone from the global south, from a developing nation, someone influenced by liberation theology. Here's a person who grew up in our American democratic capitalism in the best sense, and is fully capable of engaging it very directly.

Pope Francis was the first Latin American pope, and his papacy was recognized for his commitment to the poor and environmental stewardship. (Photo: Korean Culture, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 2.0)

O'NEILL: Erin from a sort of broad perspective, what is the connection between the Catholic faith and the environment and the climate? What is the connection there?

LOTHES: First of all, just honoring our life, our existence on this planet, is an act of faith. And then in the sense of our interdependence with all creatures, we are here to care for each other, to care for our neighbor. And in a time of climate crisis, that means attending to healing the wounds of the planet and the degradation of the planet that is challenging the well being and the health and the survival of people all over the world. So the great command that Jesus taught is to love your neighbor as yourself. We can't do that anymore without caring for creation, because the damage done to creation is undermining the well being of the neighbor. And what Pope Francis stated so beautifully and clearly in Laudato Si is there's a third dimension. He just put it out there. We love God, we love our neighbor, and we have to care for creation these are interrelated relationships. The teaching is clear. It's part of Catholic social teaching. It's recognized as a moral obligation for all Christians. Just as so many faith traditions around the world have clear teachings about the need to care for creation and to care for our brothers and sisters.

Dr. Erin Lothes is an educator, theologian, and public speaker committed to creating community action for climate justice. (Photo: Courtesy of Erin Lothes)

O'NEILL: Dr Erin Lothes is an environmental theologian and the author of Inspired Sustainability, Planting Seeds for Action, about what inspired successful interfaith care for creation. Erin, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

LOTHES: Thank you, Aynsley, it's been a great pleasure to talk with you about care for creation and Pope Leo XIV. Thank you so much for having me.

Related links:

- National Catholic Reporter | “Before He Was Pope, Leo XIV Said It’s Time for Action on Climate Change”

- Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology | “The New Pope, Leo XIV, Has Spoken Out About Urgent Need for Climate Change Action”

- Learn more about Erin Lothes

[MUSIC: BIRDNOTE THEME]

Birdnote®: Toucan - Tropical Icon

There are over forty species of toucan. Shown here is a Cuvier’s toucan. (Photo: Pablo BM, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: In the Peruvian Amazon not far from where Pope Leo XIV lived for many years, you can find a most distinctive bird with a comically huge bill.

BirdNote’s Mary McCann has more.

https://www.birdnote.org/podcasts/birdnote-daily/toucan-tropical-icon

BirdNote®

Toucan - Tropical Icon

Written by Adam Sedgley

[Amazon rainforest sounds, replete with bird life]

MCCANN: In the Amazon, heat and humidity virtually smother you. Although a cacophony of birdcalls surrounds you, it’s hard to see even a single bird. Then one call, emanating from a cathedral of vegetation, catches your ear.

[Call of Cuvier’s Toucan]

Could this piercing and cheerful yelp be the same sound you remember from a Saturday morning in your childhood? It’s the call of a toucan, the tropical icon and inspiration for Toucan Sam, that colorful “spokesbird” for Froot Loops® cereal.

Characterized by massive yet surprisingly light bills, the 41 species in the toucan family are found only in Central and South America.

The species we are hearing now is a Cuvier’s Toucan [call of Cuvier’s Toucan].

It has a jet-black body and a spotless white bib. Its black bill, nearly as long as its body, is rimmed with vivid yellow and baby blue. That the toucan hops through the trees as it forages for fruit adds to its comical demeanor. But don’t expect this bird to lead you to a bounty of rainbow-colored sugar puffs with its nose. Toucans can’t smell.

[Call of Cuvier’s Toucan]

So why does Toucan Sam – or any other toucan – have such a large bill? Turns out that they can conserve heat – or release it – with those giant beaks. I’m Mary McCann.

###

Sounds of the Amazon rainforest and Cuvier’s Toucan provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recordists are not known.

Senior Producer: Mark Bramhill

Producer: Sam Johnson

Content Director: Jonese Franklin

© 2013 Tune In to Nature.org December 2016/November 2024 Narrator: Mary McCann

ID#010506CUTOKPLU CUTO-01b

CURWOOD: For pictures, flap on over to the Living on Earth website, loe dot org.

Related link:

Learn more about the toucan on the BirdNote® website

[MUSIC: Fuerza Andina Del Perú, “Chiclayo,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HUhnLR4rhMU ]

O’NEILL: Just ahead, exploring the role of chemical exposure in autism. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Wes Montgomery, “Old Folks” on Way Out Wes, by Robinson/Hill, Not Now Music]

Autism and Chemicals

Autism spectrum disorder covers a range of presentations, characteristics, and support needs. Dr. Temple Grandin is a gifted animal communicator and a well-known autism rights advocate. (Photo: Steve Jurvetson, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Autism spectrum disorder is now diagnosed in about 1 in 31 children in the United States, based on a regional study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released in April. That research showed a 70% increase in prevalence among children in just four years. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., who has previously tied the condition to vaccines, has instructed his department to determine the root causes of autism by this fall. Over the years, better awareness and changing diagnostic tools have contributed to rising cases of autism in adults and children. And growing scientific evidence points to the role of exposure to toxic chemicals especially during early development. Studies over the past few decades have shown that even low levels of exposure to substances like lead, mercury, PCBs, bisphenols and phthalates can alter brain development, reduce IQ, and increase the risk of conditions like autism. A 2025 report in the New England Journal of Medicine emphasizes that children are far more vulnerable than adults to these chemical exposures, especially in utero and early childhood. To help us understand the complicated factors that give rise to autism we’re joined by Dr. Philip Landrigan, a pediatrician, professor at Boston College, and one of the world’s leading experts on toxic exposure from plastics and pollution. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Dr. Landrigan!

LANDRIGAN: Steve, it's a pleasure to be with you.

CURWOOD: Dr. Landrigan, please briefly explain what Autism Spectrum Disorder is and what are the key differences within that spectrum.

LANDRIGAN: Autism Spectrum Disorder is a disorder of the brain. It's not a psychological condition. It's actually a brain disorder. It can range in severity from quite mild to profoundly severe. Two thirds of the children who have autism also have some degree of cognitive impairment, reduced IQ. Some have increased brain size. Some have epileptic seizures. Some have speech problems and motor problems. And yet, on the positive side, some have amazing, unique skills, like some children with what used to be called Asperger's syndrome can perform amazing feats of memory or mathematics. So it's really quite a range of conditions. Hence, the term spectrum.

CURWOOD: The Centers for Disease Control is reporting an increasing prevalence of autism being diagnosed. What does this increase mean, and what factors might be driving it, do you think?

Falsified research from the 1990s sparked a misinformation campaign tying autism to early childhood vaccinations. This has since been debunked by numerous studies. (Photo: Helapolis, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

LANDRIGAN: Well, it's probably driven by several things. To be sure, there's better recognition of autism at all levels of society, among health professionals teachers, but also among parents and those who care for children. And better recognition is certainly part of the story, but it by no means is it the whole story, and there is absolutely a rise in autism spectrum disorder among American children. The most recent statistic from CDC indicates that it occurs in one child in 31, that's up from one in 36 a year or two ago, and from one in 88 back in 2012 and one in 166 children back in 2004. So it is really, really going up, and that's far too rapid to be purely genetic explanation. When I was a pediatric resident at Boston Children's, which was in 1970, I think I may have seen one child with autism in in two years, and today, children with autism are ubiquitous at a place like Children's Hospital. So there is very definitely a real increase going on.

CURWOOD: Let me ask you about what scientific evidence, if any, that links endocrine disrupting chemicals to autism or broader neurodevelopmental issues in children.

LANDRIGAN: There have been a whole series of toxic chemicals that have been linked to problems with brain development. Going back 40 or 50 years, the first of these chemicals that we recognized were lead and methylmercury, and then PCBs, certain pesticides. And more recently, it's come to be understood that phthalates and bisphenol A's, both of which are endocrine disruptors, are among the chemicals that can disrupt children's brain development and can result in a range of conditions, autism among them.

A number of chemicals found in plastic food packaging have been linked to neurodevelopmental conditions, such as autism spectrum disorder. (Photo: Rlsheehan, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Now, where does this exposure take place? If it's related, is it in the parents? Is it in the child, him or herself?

LANDRIGAN: Well, the most worrisome exposures, the most dangerous exposures, are the ones that occur during the nine months of pregnancy, when a child's brain is still growing and developing, which is an incredibly rapid, complex and therefore easily disrupted process. And exposure can occur via various routes. If toxic chemicals such as insecticide or phthalates get into a mother, those chemicals can cross the placenta from the mother to the baby and get into the baby's brain and cause damage. And then, after the child is born, the child can become exposed to these chemicals through their food, their drinking water, through playing on the rug, hand to mouth behavior, and even through inhaling the chemicals, if they're volatile in the home environment.

CURWOOD: So, looking at chemical exposure, how important do you think it is looking at these neurological, these neuro developmental issues for children, including autism spectrum disorder? I mean, how important are chemicals, do you think for this process?

LANDRIGAN: Chemicals are an important part of the story here. They're not the whole story. When I think of complex disorders like autism, I envision that there's always a mix of genetic factors and environmental factors in play. Kenneth Olden, the distinguished scientist who was the director of NIEHS for many years, used to say that genetics loads the gun and the environment pulls the trigger. Certainly, some children are genetically predisposed to conditions like autism, but autism may not develop unless there is some kind of a toxic environmental exposure that then triggers the disease. And I think the reason for the increase that we've seen over the past three or four decades is that children are being exposed to more and more external factors. Chemicals are one of them, not the only one, and these factors are interacting with children's genes and producing the condition that we call autism.

Leaded gasoline was phased out of many countries starting in the 1970s for a variety of reasons, including impacts on cognitive function and neurodevelopment. It is still permitted in US aviation fuel. (Photo: Ramon FVelasquez, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Phthalates are an endocrine disruptor that's often found in fast food wrappers and such like that. How easy or hard is it to point a finger at something like the phthalates that you find in fast food as being part of this epidemic?

LANDRIGAN: Yeah, it's probably part of it. Phthalates damage the brain. Phthalates cause symptoms of autism in some small percentage of children who are exposed to them. So, I think it's part of the problem, the phthalates in food stuffs, fast food and others, mostly get there from plastics. Phthalates are used in formulating plastics, and they don't stay in the plastics. They escape from the plastics, and they get into the food. So one way to reduce our exposure to phthalates is try to avoid food that's packaged in plastics, which I know is not easy to do in today's world, but at least, make the effort minimize exposure. Try to avoid highly processed food, try to avoid fast food, and whenever possible, eat organic.

CURWOOD: Dr. Landrigan, to what extent is the rise in plastic production and distribution in our society over the last few decades linked to this rise in autism? What evidence might there be for that or not?

LANDRIGAN: Well, the two trends certainly line up with each other. Global plastic production has increased 250 times since 1955 and in fact, the global production of plastic is accelerating as we speak. It's on track to double by 2040 and triple by 2060 and the reason it's going up so fast is that the manufacturers of plastic have come to understand that there is great deal of money to be made in single use plastic, stuff that people use once and throw away, and many of those single use plastics contain the very chemicals that we're talking about here, such as phthalates and bisphenols.

CURWOOD: Some have advanced the argument that vaccines are behind autism. As an expert in pediatric environmental health, how do you respond to that claim?

Dr. Philip J. Landrigan is the Director of the Program for Global Public Health and the Common Good at Boston College. (Photo: Courtesy of Philip Landrigan)

LANDRIGAN: Well, that theory arose 25 years or so ago when it was observed from time to time that a child who had received a vaccine developed the symptoms of autism a week or two later. A doctor in England named Andrew Wakefield was the first who first proposed this theory. He had observed several children who developed autism in the weeks following vaccine. It turns out afterwards that he had fabricated a lot of his data, and that, in fact, he was trying to market a treatment for autism at the time, but nonetheless, Wakefield's theory took hold and became widespread on the internet. I think what's going on here is that most cases of autism, most clinical manifestations of autism, show up in children between the ages of one and three, and it's precisely in that same age range, one to three years old, that children receive so many vaccines to prevent their death from terrible diseases like measles and pertussis and tetanus and others. And so if you're vaccinating millions of children, some of whom are destined to develop autism at around that same time in life, it's inevitable that some of the children who get vaccinated are going to show up with autism in the weeks after vaccination. To address this issue, the scientific community has taken this issue very seriously and to address it, scientists in this country, in the UK, Scandinavia, Japan have launched major studies looking at the association between vaccines and autism and not one of them, none of them at all, have found a credible linkage between vaccines and autism. I think the most telling of these studies, most informative is a study that was undertaken in Yokohama, Japan, the province of Yokohama, the port city by Tokyo, and in that prefecture, the Japanese government decided to completely suspend MMR, measles, mumps, rubella vaccination for a period of about two years, because rates of autism were going up. They were concerned that MMR might be a driver, so they suspended all vaccination. What happened was that rates of autism continued to go up. A couple of kids got sick with measles. They said, enough is enough. They reinstated vaccines. Children were protected against measles, and yet autism continued to rise.

CURWOOD: What do you think is the most important message to take away from the ongoing scientific and public debate about autism and environmental toxins?

LANDRIGAN: The most important thing to understand here is that children in today's world are exposed to 1000s of chemicals in every aspect of their environment. Because of weakness in federal law in this country, fewer than 20% of those chemicals have ever been tested for toxicity. What this means is that American children are being exposed every day to chemicals of unknown hazard. We have to reduce children's exposure to these hazardous chemicals in food, in drinking water, in toys, in children's general environments.

CURWOOD: Dr. Philip Landrigan is Director of Global Program in Public Health and Common Good at Boston College. Thank you so much for taking the time with us.

LANDRIGAN: Thank you, Steve, a pleasure.

Related links:

- CDC Study:Data and Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder

- New England Journal of Medicine: Manufactured Chemicals and Children's Health

- Learn more about autism.

- Explore ways you can reduce your exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals.

[MUSIC: Ben Tofft, “Silver City,” 2018]

"Countermeasures"- Dunlin

Dunlin asleep in the saltpans. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: After the break, we’ll hear about a shorebird success story. But first, here’s a moment Living on Earth’s Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender observed among different shorebirds last fall.

Countermeasures

Dunlin

Parker River National Wildlife Refuge

Newburyport, Massachusetts

© 2024 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

LENDER: Dunlin have gathered for sleep. Out on the saltpans. More than a hundred. The crest of a great wave, South. They stand stilted on one foot, faces turned all the way round and tucked between shoulders, breathing in their own feathered warmth. The saltpans are shallow, the bottom muddy; one pops up with the effort of pulling free and pogo sticks to a different spot. Indicative of an edginess that ultimately makes them leave; a short flurry of takeoff and land, same thing.

At sunrise, beneath the long shadow of the sand dune they are already feeding. Like Singer sowing machines, the foot-peddle kind my grandmother owned. Industrious little grandmothers, that's what they look like, their stubby little beaks with that downdip at the end going, chakka-chakka, chakka-chakka, chakka-chakka chukka. Stitching for pennies, no time for rest.

And –

Whoofff!

The entire flock is airborne.

Turn Left! Turn right! Towards me now, the knife edge of their wings all in the vertical and all in line.

And TURN!

Wings blue-white in the dune’s blue-grey shadow.

TURN!

Wings red-gold as they rise into sunlight.

TURN!

Drop low wings kissing water.

TURN! TURN! And TURN…

Falcon.

That’s what put the dunlin up.

Dunlin cornering to evade the intruder. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

One of the regulars thinks, merlin. Kestrel, merlin, peregrine even, the same for all of them, the half-illumination of early morning works to their advantage. Reduced, so the dunlin hope, by the paradox of confusion in synchronous flight.

As the sun clears the dune the flock breaks into clans and families, to settle in the tall marsh grasses where they continue to feed, hiding as much as they can from the all too revealing day. Until dusk. When they return to the saltpans, out in the open, waiting on the dark.

While across the marsh now a northern harrier glides, her eye catching the last radical of light, an ancient and indifferent star.

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Read Mark’s field note here

- Much of the wildlife of the National Wildlife Refuges along the Eastern seaboard can be found at Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife

- About Parker River NWR

- More of Mark Seth Lender’s photography can be seen at

[MUSIC: Jack Johnson, “Only the Ocean,” on To the Sea, written by Adam Topol, Jack Johnson, Merlo Podlewski, Zach Gill (Brushfire and Universal Republic 2010)]

O’NEILL: Coming up, why fortunes have risen for the shorebirds known as oystercatchers. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Zander Jazz Trio. “Let There Be Love” on Misty, Zander Jazz Trio]

Oystercatchers Bounce Back

An American Oystercatcher in the sand of San Carlos Bay, Florida. (Photo: Peter Wallack, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. So, Steve, I know you, like many of our listeners, are a birding aficionado. I want to know if you recognize this.

[OYSTERCATCHER CALL]

CURWOOD: Hmm…brings up images of a sandy beach and a blue ocean, Aynsley, I think it sounds like a shorebird to me.

O’NEILL: Got it in one, Steve, that is an American oystercatcher. It’s the focus of a major conservation win for shorebirds, which, as I understand it, is a particularly vulnerable category of birds.

CURWOOD: That’s right, I think a study came out a few years back that show that a majority of American shorebird species were in decline, something like 90%. And I’m not sure I’ve ever seen an oystercatcher. What’s this bird like, and how much of a conservation success is it?

O’NEILL: It’s a big success, and I’ll tell you how it’s recovery is still moving ahead in a moment. But you can start with understanding it’s a pretty fun bird, Steve, I’ve found some great pictures while looking into this story. And we’ll post some of those pictures to be sure, but here’s a descriptor from someone who knows a little more than I do.

HURDLE: It’s this fairly large shorebird with a black head and a black back and a very large bright red bill and red eyes. And, and it has, some might say, a sort of comical appearance and, and so it was seen as being a prime candidate for a concerted conservation campaign.

O’NEILL: That’s journalist Jon Hurdle, from our media partner Inside Climate News, who I called up after reading his article about the American Oystercatcher Recovery Campaign.

CURWOOD: Okay, now I’ve got a picture in my mind. A bright red bill definitely sounds distinctive.

O’NEILL: And their feathers are too, they were actually nearly hunted to extinction in the 19th century for their plumage, as well as their eggs.

CURWOOD: Ah, so is that the focus of the recovery campaign?

O’NEILL: Actually, the species mostly managed to rebound after the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1918. But today oystercatchers have to contend with habitat loss, nest disruption, pollution, climate change and more, and all that led to its decline. Here’s Jon Hurdle again.

HURDLE: Like many other shorebird species, its numbers were declining all around its American range, which goes all the way down the Atlantic coast and throughout the Gulf Coast as well. And, the conservation team that I've been writing about, they chose the oystercatcher because, partly because it was a charismatic species.

O’NEILL: So, the campaign came together with a coalition of around 40 different nonprofits and government agencies, all working to keep this charismatic species alive and well. The lead of the campaign is a shorebird scientist at Manomet Conservation Sciences named Shiloh Schulte.

SCHULTE: We in the conservation community looked at this whole assessment of all these different shore bird species and said, which ones are at risk? Oystercatchers rose to the top as one of the species that was most in need of conservation because they have a very restricted range. They're only found right along the coast and only in a limited area of the coast, and then they have very low nest survival.

CURWOOD: So, as Jon said, they might be found up and down the coasts of the United States, but sounds like they’re pretty picky about their habitat.

Oystercatcher populations have rebounded around 45% since the recovery campaign began in 2008. (Photo: Matthew Paulson, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O’NEILL: Exactly. Shiloh told me these birds are at particular risk from both natural and human factors. See, oystercatchers don’t make nests in a tree, but rather lay their eggs on the ground right above the high tide line.

SCHULTE: They’re susceptible to things like a storm coming and washing out the beach and washing their eggs away, but also a human walking along the beach and stepping on their eggs, or driving on the beach and running them over, which has happened, or simply just going and putting down your beach blanket and hanging out for an hour 20 feet from an oystercatcher nest, you don't realize it's there. The birds stay off the nest. The eggs get exposed to sun. And there's all sorts of things that can happen as a result of human intervention or human interaction that causes these nests to fail. And that's what was happening.

CURWOOD: Nesting on the ground will definitely make a species vulnerable. And I remember hearing the whippoorwill often in my youth that simply isn’t around much anymore for that very reason.

O’NEILL: And according to Shiloh, that’s basically why the campaign’s ultimate success came not from oystercatcher management, or even ecosystem management. It came from people management.

SCHULTE: So where humans come in is that if we are out there just having fun on the beach, we can inadvertently cause an oystercatcher to lose its entire season's worth of effort on trying to raise babies so it can lose the eggs, lose the chicks. What we do is we, we sometimes will put up fences or like posting signs that say, bird nesting area, please keep out. But humans are not good at reading signs. They're not good at following directions, and they don't necessarily understand why this matters. You know, they're just out there for a little bit. So we have somebody that goes out there and has these conversations like we're having right now about oystercatchers, like, why do I care about oystercatchers?

CURWOOD: So that that was the bulk of the campaign’s efforts. And you said this was a conservation win; so how successful has it been?

O’NEILL: When the campaign started out in 2008, there were around 10,000 oystercatchers in the entirety of North America. Which, to be clear, is still pretty good for a shorebird species. But the Oystercatcher recovery team knew they could do better, and by 2023, 15 years later, they were up to about 15,000. A lot of that came from when the campaign started to collaborate with the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation.

SCHULTE: We very, very quickly started to see a turnaround in the numbers. We started to see more baby oystercatchers hatching, more baby birds fledging, making it to adulthood, and then those adults surviving long enough to get to adulthood, which takes about four years for an oystercatcher coming back to the beaches and then starting their own broods and nests and that success started to build. And when that happened, we started getting more and more organizations wanting to be involved, bringing their own resources into the group.

CURWOOD: That’s a sizable jump, but I wonder what will happen with all these government budget cuts and the like. I mean, how vulnerable is this success right now?

O’NEILL: I thought the same thing, Steve. Here’s Shiloh again on that.

SCHULTE: It's a fragile increase because it requires yearly, annual management. It's not something we can point to and say we're going to walk away and be done. There's the existential threats, like sea level rise that could wipe out huge sections of habitat. There's coastal erosion and all kinds of things that are a risk for this species. But right now, and over the last 15 years, the work that we've been doing is showing the results that we were hoping for, maybe even better than we were hoping for.

O’NEILL: Although the recovery is definitely vulnerable, it’s still been a massive win for conservation. And now, the American Oystercatcher Recovery Campaign wants to try to extend their practices to other struggling shorebird species. And with any luck, those recovery campaigners can feel the same way Shiloh has after years dedicated to this project.

SCHULTE: When I moved to Maine, there were no oystercatchers near me, and now there's a pair nesting just a few miles from my house, along the beach or along the coast. And so I can go down there, and I can see these oystercatchers that are here now because of the work of this group that I've been part of for the last couple of decades. And so it's, it's really gratifying. It's really exciting to see.

O’NEILL: So, Steve, definitely keep your eyes and ears peeled for those bright-billed birds when you’re at the beach this summer.

CURWOOD: I will, and I’m so glad to hear this good-news story, Aynsley!

O’NEILL: I know Steve, we all love good news!

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “Oystercatcher Recovery Campaign Offers a Rare Success Story about Shorebird Conservation”

- Learn more about the American Oystercatcher Recovery Campaign at Manomet

- Click here to learn more about Shiloh Schulte

[OYSTERCATCHER CALLS]

Defending Climate Science

The American Geophysical Union and the American Meteorological Society are joining forces to keep momentum for climate research in the US despite disruptions to Federal funding and projects. Pictured above is the entrance to the American Geophisical Union’s headquarters in Washington, DC. (Photo: sikeri, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: One of the steps the Trump administration has taken to undermine climate science throughout the executive branch included the dismissal of the roughly 400 scientists working on the National Climate Assessment. That’s a key government report published every few years on climate risks and impacts, and this decision comes as communities across the U.S. face escalating climate threats, from record wildfires to intensifying hurricanes and rising sea levels. In response to this disruption, the American Geophysical Union and the American Meteorological Society have announced a collaboration to support U.S. climate science, including a new special collection of studies. Joining us to discuss this effort and the broader implications for science in the US is Brandon Jones, President of the 60,000 member American Geophysical Union or AGU. Brandon, welcome to Living on Earth!

JONES: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: The AGU—the American Geophysical Union—and the American Meteorological Society have announced the creation of a special collection for issues on climate change in the US. To what extent are you just trying to rebuild what's been torn down or move forward with yet a new model?

JONES: The National Climate Assessment is a congressionally mandated report, and so Congress and the Federal Government are going to have to figure out what's going to be done for that report itself. And so the special collection that AGU and AMS are coming together to support is not to replace that. You can look at it as there's a crack in the system they've released all these authors and things are going to be stymied or halted. Some may think: Well, someone needs to fill in that crack with that same type of report. But I would say, Well, if the crack gets filled in, are we supporting a system that's already crumbling, or are we trying to hold up a system that just needs to part of it, not the whole thing, fade away, so that something new can show up? And I think the special collection example is where we've seen a crack, and we see the daylight and what's possible on the other side. And instead of trying to replace, we're just going to do something new.

CURWOOD: Tell me, what's the timeline here for the special collections, and who is getting invited to contribute?

Brandon Jones, 2025-2026 AGU President, has served on AGU’s Board since 2017 while spearheading initiatives to expand STEM access and career pathways for early-career researchers. (Photo: Courtesy of Brandon Jones)

JONES: So the timeline right now, since we're in the first phases, where we don't have an actual set time, we're thinking maybe over the next two years or so that we'll have the opening of the special collections for submissions, and it is wide open to the scientific enterprise, and we're also—we being AGU and AMS—are kind of putting out a call to action for other professional societies to come and join this, so the more journals that are involved in this growing library in this special collection, the better, because that way we'll reach a wider swath of our scientific community and have even more extensive data and research to share.

CURWOOD: One of the criteria for people to participate in this is peer-reviewed research. Remind us, for people who maybe don't quite know what peer review is, what is that?

JONES: Peer review, in my opinion, is part of that special sauce that makes scientific method as unique as it is among other sectors. So if you're a scientist and you've analyzed the data that you've collected, you write it up, and then you submit it to other experts in your field or discipline or related disciplines, basically for them to just shred it. The peer reviewers as experts, if they give a thumbs up, what they're saying is that the idea, the concept, the experimentation, the implementation, the analysis, the conclusions drawn, all make sense, and the results that then are coming out of this work can be trusted.

CURWOOD: What do the dismissal of the National Climate Assessment authors tell us about the current challenges of integrating scientific expertise into policy making do you think?

The Trump Administration dismissed all contributors to the National Climate Assessment on April 28th. The NCA is the US government’s comprehensive report on climate change impacts and risks in the US. (Photo: WhiteHouse.gov, Public Domain)

JONES: This, I think, is where not just the general public needs to be more aware of the importance of science and decision making, but scientists themselves, in my opinion, could be encouraged and maybe mobilized to become a bit more active in the political space. Traditionally, speaking out on issues that are of public interest aren't really how scientists are trained, and in some instances, there's activation energy against being too much of an advocate for something, and there's a sense that if you start to weigh in on a particular issue from your scientific expertise, somehow you're diluting the objectivity that makes science an interesting and trusted enterprise. But I would argue that if you're a scientist that receives federal funding, you're already in the political fray, because that funding is coming from a congressionally mandated process, and it's being administered by an administration that was elected and has priorities already in place. But the bigger picture is we're facing existential problems, climate change being one of them, global pandemics, AI and cyber security being another. We need the scientists and we need the data, the verified data, to help decision makers do the best that they can for the citizenry.

CURWOOD: Now, we've seen science misinformation proliferate in recent years. How do you feel this has affected both research efforts and the public trust in scientific institutions?

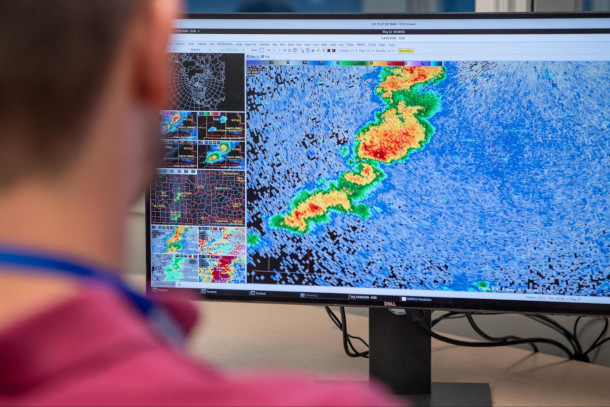

Emergency prediction systems rely on data and scientists. Initiatives like the Watch-to-Warning Experiment aim to enhance severe weather communication by optimizing risk messaging between watches and warnings during evolving storms. (Photo: NOAA NSSL, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

JONES: I will say that, as a former high school educator, there's this coupling of misinformation with general 'unknowing' among much of the citizenry. If I look at the K-12 system—the public education system—the responsibilities and the overload that our teachers and administrators and guidance counselors are under… and I'll say this, just me personally: teaching students to take tests instead of opening up opportunities for learning, and then the content that is being provided… So what—Certainly in the sciences, you have core content in the K-12 system, like chemistry and biology and physics, but you have very little Earth System Science—oceanography, atmospheric science, solid earth science, and environmental science. And so, by the time students graduate high school, and they move into—they go to college or they're off into their careers—the general knowledge about how the earth works just isn't there. And so, once they're into adulthood and their careers, depending on their news environment—in other words, where they get their information from—if they can't filter the information with foundations from their early education or even their college education—where there's trusted information—then people might be swayed by misinformation.

CURWOOD: This also relates to my profession, that is journalism. For many years on the question of the climate, the supervising editors would say, "Well, some people say there's climate disruption, other people say there isn't. Let's split the difference". How does that work in science?

Tornado damage near Putnam County, Tennessee, USA in March 2020. (Photo: Chuck Sutherland, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

JONES: So that example there is interesting, because 97 to 98% of climate scientists around the world agree that the climate is changing due to human activity—and so, if the average citizen is watching a journalistic piece on climate change, and the two talking heads that are on the screen are a climate scientist and a climate denier, that average citizen might think, "Okay, well, this is really a balanced argument—who's to say who's right?" But if I were a producer—and I have no idea about how that happens in your world—I would maybe put 97 climate scientists up and three deniers and then have the debate… and see what the average citizen would think about that.

CURWOOD: Now, how will the American Geophysical Union and the American Meteorological Society ensure that this research actively counters politicized narratives and empowers everyday people?

JONES: Now, that's a great question. I know on the AGU side, I can't speak for AMS, but we have a stellar communications team internally on the staff side, and so as an organization, for decades now, we've engaged with mainstream media. Now we also have a strong social media presence, we're on multiple platforms, but we also have a policy department at AGU that engages with Capitol Hill on both sides of the aisle and also empowers our members through trainings and templates how to be advocates at the local level or even the state level. So there will be multiple ways for this information to reach not only the academic community and the broader research enterprise, but also the general public.

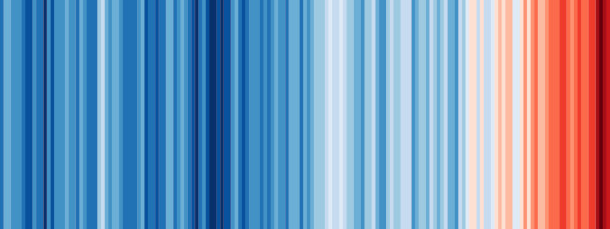

Created by climate scientist Ed Hawkins, the "warming stripes" use a striking gradient of blue-to-red vertical bands to visualize Earth’s rising temperatures since the 19th century. Each stripe represents a year’s average temperature deviation from the long-term norm. (Photo: Ed Hawkins, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: Facing the dismantling of climate science infrastructure and trust, what's at stake if this just continues unchallenged?

JONES: Just to be blunt, lives are at stake. For example, the climate is changing. We know that severe storms are increasing in their intensity and their frequency. So if you have an agency like NOAA, where the National Weather Service is housed, and you have forecasting models for early warning systems. Those models are based on data, and that data is being collected, not only through instrumentation, but also from scientists, but even through the instrumentation. The scientists are the ones that are responsible for ensuring that data is of high quality. If there's a disruption in that flow of information, a removal of scientists or expertise, there are going to be implications on how trusted that forecasting model is, and there's going to be an impact on the early warning systems. So now we're talking about lives, we're talking about economic loss, we're talking about power interruptions, the cascade effects—everyone can imagine those. So that's just an example of what is at stake.

CURWOOD: If the present challenges are met with robust scientific engagement and public collaboration. What kind of future could we build in terms of climate resilience and policy progress do you think?

A protestor holds a sign reading ‘Denied Facts are Still Facts’ during the 2017 People’s Climate March in Washington D.C. (Photo: Edward Kimmel, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

JONES: The future is unlimited, if we can figure out how to come together. Given what's going on, the dismantling of departments and institutions and organizations across the research enterprise, and the firing of employees and all of this disruption—For me, the way to combat that is through coalitions and through cooperation and through collaboration. And I'm beginning to see lots of evidence of that happening in ways, maybe that it wouldn't have happened, or it would have happened in a longer period of time. In a very weird way, and I can't believe I'm saying this, this disruption might have given us the kick in the pants that we needed to move out of our silos and really connect with other sectors, not just in research and science, but even outside, to build the future that we really need.

CURWOOD: Brandon Jones is the president of the American Geophysical Union, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

JONES: Oh, it was my pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

Related links:

- Learn more about the National Climate Assessment (NCA)

- Visit the American Geophysical Union (AGU) official site

- Visit the American Meteorological Society (AMS) official site

- Learn about Brandon Jones’ role and mission as AGU president

- See the official announcement of the AGU and AMS collaboration and the creation of the special collections

- Read more about the dismissal of contributors to the National Climate Assessment

[MUSIC: Alan Gogoll, “Owl’s Friend,” on Owl’s Friend, 2017]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Daniela Faria, Mehek Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Sophia Pandelidis, Frankie Pelletier, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

O’NEILL: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to Matt Hillman, manager of Parker River National Wildlife Refuge. We always welcome your feedback at comments at loe.org. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth