May 17, 2002

Air Date: May 17, 2002

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

West Virginia Flood

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

Recent floods in West Virginia have damaged many homes and businesses in southern West Virginia. Many residents are blaming logging and strip mining for the floods. But, as Jeff Young reports, scientists say the causes are not clear. (05:50)

Airplane Air

View the page for this story

Flight attendants in Seattle are suing airplane manufacturers over possible chemical contamination of cabin air. USA Today reporter Byron Acohido discusses the suit with host Steve Curwood. (05:10)

Department A/Health Note

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on a new study that found teen vegetarians may be eating healthier than their carnivorous counterparts. (01:30)

The Living On Earth Almanac

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about the first steamboat ever to cross the Atlantic Ocean. The SS Savannah took off in 1819 despite many fears and doubts. (01:30)

Rural Youth Loans

/ Susannah LeeView the page for this story

Farms across the United States are disappearing. Farmers are aging and land is being swept up by developers. A program sponsored by the Department of Agriculture aims to keep young people interested in farming with low interest loans to start their own businesses. Susannah Lee reports. (07:20)

Malformed Frogs

View the page for this story

Atrazine is the most commonly used herbicide in the U.S. But a new study shows that it can turn male frogs into hermaphrodites. Host Steve Curwood speaks with UC Berkeley biologist Tyrone Hayes about his research into the weed-killer's effects on these amphibians. (05:10)

Noise Map

View the page for this story

British noise specialists will be taking sound checks of the United Kingdom in a two-year effort to map noise levels throughout the country. Host Steve Curwood talks with John Hinton, a noise specialist who put together the first ever noise map of an entire city. (03:00)

Department B/Animal Note

/ Maggie VilligerView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Maggie Villiger reports on a novel survival technique for a caterpillar -- producing its own insecticide. (01:20)

Eucalyptus

/ Louise RafkinView the page for this story

A large and majestic tree has divided the town of Bolinas in northern California. The eucalyptus was once called "the wonder tree" for it’s ability to grow in the coastal scrub. But some say the non-native destroys sensitive habitat and should be cut down. Louise Rafkin has the story. (06:30)

Manatees

/ Angela SwaffordView the page for this story

Manatees, the sea cows that inhabit the waters of Florida, depend on natural warm water springs to survive the winter. But thanks to development, those warm water sources have diminished over the years. So manatees have come to depend on the warm water discharge of power plants. But now, they face losing even these man-made refuges. Angela Swafford reports. (09:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

REPORTERS: Jeff Young, Susannah Lee. Louise Rafkin. Angela Swafford

GUESTS: Byron Acohido, Tyrone Hayes, John Hinton

UPDATES: Diane Toomey, Maggie Villiger

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From National Public Radio it’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Researchers at UCal/Berkeley say that levels of the herbicide atrazine, commonly found in rainwater and streams, can change the sex of frogs.

HAYES: We find effects starting at point one part per billion. And what’s shocking is that point one part per billion is incredibly low. Atrazine can be found in rainwater in Iowa. It can come off of corn fields as high as parts per million in spring.

CURWOOD: Also from Florida, how endangered manatees have become dependent on the warm water discharge from power plants. Some have gotten into trouble.

PERKINS: And they just stayed there and stayed there and stayed there, thinking that the warm water would come back, and it didn’t. And if that warm water isn’t there and they’re still conditioned to go to that site, they will ultimately perish. And that’s what happened in this case up in Jacksonville.

CURWOOD: That and more on Living on Earth, right after this.

West Virginia Flood

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Recently, a U.S. District judge in West Virginia ruled that it’s illegal for mine operators to dump debris from mountaintop removal into valleys and streams. That ruling is being appealed by the Bush administration. But some believe this mining waste, as well as hillside logging, have contributed to the latest disastrous floods in West Virginia. In the past 10 months at least a dozen people have been killed by two major floods in the southern part of the state. Jeff Young of West Virginia Public Broadcasting reports from McDowell County, which was hardest hit by the recent high water.

[SOUND OF FLOWING WATER]

YOUNG: The flash floods of May 2nd damaged or destroyed a third of the homes in the town of Coalwood. It’s the second major flood in 10 months. Coalwood residents wonder if their town’s two namesake industries are responsible.

TABOR: I was born and raised right here in this camp. I’ve never seen it like this. This is unreal.

YOUNG: Rollins Tabor’s home was surrounded by water after a landslide diverted a stream into his street. The slide is just below a steep, treeless logging site.

TABOR: They’ve logged it and logged it and logged it and logged it, and it’s literally destroyed it. I mean, that’s why all the water has come in here on us.

YOUNG: Logging in McDowell County is up by one third in recent years. Land logged in the last three years covers some six percent of the county.

[SOUND OF SHOVELING]

YOUNG: In nearby Turnhole Branch, even some homes far uphill from the swollen Tug Fork River did not escape damage. Large, jagged rocks, some the size of bowling balls, came tumbling down with water from the top of the hill. Lorenzo Thomas stands among the rocky debris that now paves his neighborhood.

THOMAS: Yeah, it’s a whole lot buddy, it’s too much. It shouldn’t have happened. They did something wrong up there. All this wouldn’t have come down here with that water. It came from some strip job up on the mountain, back up at the end of the hollow.

YOUNG: The strip mine above Thomas’s house is one of hundreds of abandoned surface mines in the state, places where bankrupt coal companies walked away from the damage caused by years of bulldozing and blasting. At this site, waste rock from the cut hillsides was piled around the mine, but the heavy rains sent tons of that rock hurtling onto the homes in the hollow below. An analysis of state mining records by the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition shows old and active strip mines covering more than 18,000 acres of McDowell County.

Mountaintop removal mines also bury hundreds of miles of streams in the state’s southern counties as companies blast the tops from hills and dispose of the waste rock and dirt in massive valley fills. West Virginia University geology professor Steve Kite says mining is making unprecedented changes to the land.

KITE: This southern West Virginia landscape is being transformed by the coal mining. And the amount of earthy materials being moved around in southern West Virginia’s higher than any place in the lower 48 of the United States.

YOUNG: Residents suspect those changes in the landscape change the way water runs from the hills during rainstorms. They say trees that once absorbed and slowed run-off are gone and erosion fills streams with silt, making flooding more likely and more severe. But scientists like Steve Kite say the issue is complex.

KITE: A lot of the damage from the July 2001 floods were related to these old mine spoil piles failing, adding sediment to the load of the streams, and then this sediment was used by the streams in scouring and eroding and making the situation worse. But, in general, the well-done, well-completed mountaintop removal valley fill sites were not as big of a problem as the abandoned mines.

YOUNG: Industry representatives say there’s no evidence linking mining and logging to flooding frequency or magnitude. Bill Raney heads the West Virginia Coal Association.

RANEY: Oftentimes in the mining process you have benches. We have drainage structures. We’re required by law to capture every big of drainage that touches a mine site, so that mining actually impedes the run-off and slows the peak discharges. So we feel like it certainly has, in some cases, a beneficial effect.

YOUNG: But trial lawyer Stewart Calwell says the mines have a cumulative impact on the area. Calwell represents flooded residents who have joined a lawsuit charging mining and timbering companies contributed to the flood damage.

CALWELL: The fact of the matter is, when there is a critical disturbance that can happen to hillsides that so affects the rate of delivery of water to the natural drains that flash flooding occurs. There’s a right way to mine, there’s a right way to log, and obviously, in West Virginia, we’re doing it all wrong.

YOUNG: Calwell says 1,500 people have joined the suit so far, and he expects more clients as people assess damage from the recent floods.

[SOUND OF FLOWING WATER]

YOUNG: Back in Coalwood, the damage is enough to make longtime residents like Frances Weaver want to leave for good.

WEAVER: I’ve been here 17 years and I’ve fought this water over and over and over. And this time it’s worse than it’s ever been and it really got me this time, and I just don’t have the heart to try to fight it anymore. You fight so much, you run out of fight.

YOUNG: It might not be much comfort to Weaver, but about a dozen federal and state agencies are studying the possible links between mining, timbering and the area’s flooding. Federal agencies are at work on a long-delayed comprehensive environmental assessment of mountaintop removal mining. Virginia and West Virginia plan to complete studies this summer that could provide some answers to the months of muddy misery. For Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young in Coalwood, West Virginia.

Airplane Air

CURWOOD: A lawsuit pending in Seattle might change the quality of the air that we breathe in airplane cabins. The case against Boeing and Honeywell deals with the possible contamination of cabin area in MD-80s and DC-9s. Most airliners have an auxiliary power unit, or APU, that brings in air when the planes are on the ground. On these two models the APU is located near where excess hydraulic fluid and lubricants collect. Some Alaska Airlines flight attendants filed the suit claiming these toxic chemicals can sometimes get sucked in through the fresh air valve. The resulting exposure, they allege, has caused them neurological damage. Byron Acohido reported on this case for USA TODAY. He described the flight attendants’ claims.

ACOHIDO: The flight attendants claim that they have suffered a constellation of injuries that basically amount to a poisoning of the central nervous system and brain damage. They call it a constellation of symptoms and they range anywhere from bloody noses, disorientation, flu-like symptoms all the way up to chronic memory loss, the loss of the ability to multi-task. In one of the plaintiffs’ case, she’s documented having shakes of her torso and arms. Six years later, today she still has trouble with these involuntary shakes.

CURWOOD: What’s the airline’s response to these claims?

ACOHIDO: The airline’s basic response is that leaks occur so rarely as to not be a problem. And in instances when any sort of fluids leak and get into the cabin air supply do happen, that the amount of organophosphates in the particles that are circulating in the cabin air are so small as to not pose any serious health risk to passengers or crew.

CURWOOD: How common are these types of airplanes, and which airlines have them?

ACOHIDO: The MD-80s and DC-9s, there are about a little over 1,700 still in use around the world. And American Airlines is the largest operator of them; they have about 360. Delta has a couple hundred. Northwest is a big operator. And then there are operators in Europe and Asia and others in America, as well.

CURWOOD: I understand, at one point, somebody tested putting some fluid into one of these air intake valves for an airliner cabin. And what happened in that test?

ACOHIDO: Well, the test you’re referring to was a rather extraordinary experiment that was conducted by then the chief of maintenance for Alaska Airlines. Back in 1996 he was struggling to address all these reports coming back from these crews about smoke in the cabin and injury to the flight attendants and even to passengers. So he parked an aircraft, the MD-80, in a hangar and went inside the cabin with at least two other senior managers, and then they turned on the APU and instructed a mechanic to squirt eight ounces of hydraulic fluid into the air intake of the APU. And when that happened, within a matter of a few minutes the managers inside the cabin noticed what they described as a mist or a haze. And right away, they started having symptoms-- they started having eye irritations and coughs and headaches.

CURWOOD: I have to say, I’ve been in MD-80s and DC-9s where I’ve seen a misting and I always assumed that it was because maybe it was a hot day outside and the moisture was condensing inside the plane as it was cooled, or something like that.

ACOHIDO: That could be. There could be condensation, moisture, I guess, theoretically. But in order for us to independently establish whether this was happening on a more widespread basis than just at Alaska, I took a look at some documents called "Service Difficulty Reports," which are one page reports filed with the Federal Aviation Administration by airlines any time they have a mechanical problem of a certain magnitude. And what we found was that smoke in the cabin, odor, hazes, were rather widely reported over the last three decades by airlines that use MD-80s and DC-9s.

CURWOOD: Now, if this jury in Seattle finds fault with Boeing and Honeywell, what will happen?

ACOHIDO: If the jury finds for the plaintiffs, it could end up stigmatizing the MD-80/DC-9 model. But on a wider basis, I think it could maybe elevate the whole debate about whether cabin air or contaminated cabin area, especially, should be looked into more seriously. Because what we’re talking about here is one of the last few public spaces where the air supply has not been sort of fully addressed from the standpoint of health effects to just average people.

CURWOOD: Byron Acohido is a reporter with USA TODAY. Thanks so much for speaking with us.

ACOHIDO: You’re welcome, Steve. It was a pleasure being here.

[MUSIC: Jefferson Airplane, "Blues from an Airplane,"]

Related link:

USA Today Article – "Verdict expected soon on toxic air aboard jets"">

Department A/Health Note

CURWOOD: Coming up: hope and health. A modest federal program to encourage young farmers. First, this Environmental Health Note from Diane Toomey:

[THEME MUSIC]

TOOMEY: While parents might be concerned about teenagers and their fickle eating habits, a new study shows that vegetarian adolescents may have the healthiest diets. Researchers at the University of Minnesota set out to answer the question: "Do teen vegetarians eat better than their meat eating counterparts?" In, what they describe as, the first large-scale study of its kind, they asked more than 4,500 middle and high school students to fill out questionnaires about their diets. The researchers evaluated the answers based on dietary guidelines put out by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. They include the recommendation that people get less than 30 percent of their calories from fat, and they also promote a diet that includes at least three servings of vegetables a day.

Eighty percent of the vegetarians met the guidelines for fat consumption, but less than half of the meat-eating students did. And vegetarians were more than twice as likely to eat enough vegetables. Another group of students who described themselves as vegetarian but who did eat poultry and fish were also more likely than non-vegetarians to meet the guidelines. But when it came to calcium consumption, vegetarians and meat eaters alike scored the same low marks. Only about 30 percent of all students ate enough calcium-rich food. That’s this week’s Health Update. I’m Diane Toomey.

[THEME MUSIC OUT]

[MUSIC: Intellivision, "Burn/Drown," KNOW YOUR ENEMY (Archenemy – 2000)]

The Living On Earth Almanac

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: River City Brass Band, "Carnival Day," FOOTLIFTERS (RCBB Recording – 1991)]

CURWOOD: The S.S. Savannah cast off from a dock in Georgia this week in 1819 and became the first steamboat to cross the Atlantic. Some thought she would sink and nicknamed her the Steam Coffin. Frank Braynard is a maritime historian who wrote a book on the Savannah.

BRAYNARD: The idea of going on a vessel with a fire inside was so different that no one dared to do it. And it was absolutely ludicrous. Many people said, "She’ll burn up!"

CURWOOD: The steamboat housed luxurious staterooms filled with mahogany wood trim and mirrored walls, but there were no passengers willing to brave the voyage to Liverpool and no one wanted to crew the ship either. Captain Moses Rogers had to call in favors from old friends in his hometown of New London, Connecticut to fill the roster. The Savannah must have looked odd to eyes accustomed to sails with its stacks spouting heavy black smoke. Several vessels even tried to come to her rescue, thinking she was on fire. At one point she sailed on for nearly five hours before realizing a small British cutter was trying to, quote, "save her."

The Savannah eventually made it safely home with, as Captain Rogers put it, "Neither a screw bolt, or rope yarn parted." But it would take another 25 years before the rest of the world would take her lead and establish regular steamship service across the Atlantic. And for this week, that’s the Living on Earth Almanac.

[MUSIC OUT]

Rural Youth Loans

CURWOOD: Across the nation, farm land is disappearing as farmers age and tough economic times for family farms mean more and more crop land is being sold off for development. But a program sponsored by the U.S. Department of Agriculture is trying to keep young people interested in farming. It makes low interest loans available to kids with viable income producing projects. In New England, the number of applicants has been relatively small. But as Susannah Lee reports from western Massachusetts, this loan fund has given some young people a leg up in starting their own businesses.

[SOUND OF MOVING OXEN]

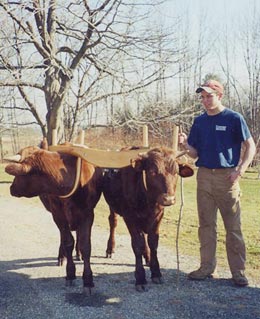

Josh Sampson with small oxen team.

LEE: Josh Sampson is an industrious 17-year-old who loves working with oxen. He shows them in county fairs, rents them out for cart rides, and uses them to haul wood, a business he’s in with his father. Today he’s using his pair of Holstein steers for logging. Many of the logs weigh a ton or more.

[SOUND OF MOVING LOGS]

LEE: These huge oxen weigh over 2,000 pounds each and, as Sampson points out, getting them around isn’t easy. So he looked for ways to buy the shiny red livestock trailer he uses to transport his animals.

SAMPSON: It’s a Bonanza trailer, and it’s just regular, plain Jane. Nothing fancy. Don’t want to be too fancy. It costs more money when you get that fancy.

LEE: Because he was under 21, Sampson couldn’t go to a commercial lender so he turned to the USDA’s Farm Service Agency for a Rural Youth Loan—- low interest loans currently available to any youth ages 10 through 20 who live in communities of less than 10,000. Jim Radentz is director of loan making for the Farm Service Agency. He says that nationwide they make over 2,000 loans annually.

RADENTZ: The objective of the program is really instructional: to give young people an opportunity to have some responsibility. Because all of the projects they would undertake through the program would involve running and operating some kind of enterprise, perhaps, on their own or caring for some animals that they may have purchased to raise.

LEE: The limit for a youth loan is $5,000. Applicants must have a sponsor from an organization such as 4-H or a vocational or tech school. And together with the local Farm Service Agency, a realistic business plan and payment schedule is worked out. With his $3,500 loan Josh Sampson bought the new trailer and acquired instant business savvy, as well.

SAMPSON: Well, right now my payment’s only $50 a month or $54 a month, so I’ve just been sending $110 because I have the money and it’s easier and quicker to get paid off. So then I don’t have to pay as much on interest.

LEE: As the USDA website video indicates, the Rural Youth Loan Program is one way the government attempts to support and promote a vanishing agricultural way of life.

VIDEO: Across rural America, the trend toward fewer farms and older farmers and ranchers continues. Small towns still look for ways to keep their young people from migrating to cities for employment. And farming and ranching families work to keep their traditions alive. But a U.S. Department of Agriculture program is making a difference.

LEE: Loan periods can range from one to seven years. Nationwide, about 6,000 Youth Loans are currently on the books, with states like Arkansas and Kentucky topping the list with over 500 loans each. Here in New England, agriculture is smaller in scale than the rest of the country, but John Devine, the Farm Service Agency’s executive director for Franklin County, Massachusetts, says that shouldn’t discourage young people with an eye for opportunity.

DEVINE: I think one of the advantages of the Northeast, or more specifically Massachusetts, is that there’s a really diverse ag population here. And we’re very nearby either urban or suburban areas that there’s a need, especially for fresh produce.

VOILAND: Well, we’ve got a whole mixture of greens in here right now, a lot of baby lettuces, a lot of arugula, mizuna, tot soy, curly cress; we’ve got a little bit of spinach, tamatsuna, a whole mixture of things.

LEE: Ryan Voiland took advantage of that opportunity early, taking out a Youth Loan while just a sophomore in high school.

VOILAND: I believe that the very first loan I took out was probably for about one to two thousand dollars, and I think, if I remember this right, that that was exclusively to finance a new walk-behind roto-tiller.

LEE: The roto-tiller was followed by a Youth Loan for greenhouse materials, and later loans for more vegetable production equipment. Now, at the still tender age of 23, Voiland has purchased his first farm, 50 acres, and is on h is way to becoming a significant supplier of organic product to area markets. With his profits, Voiland is able to afford increasingly sophisticated equipment such as a vacuum lettuce seeder.

[SOUND OF LETTUCE SEEDER]

VOILAND: Now I’m going to roll around the lettuce seeds, trying to fill up every hole.

LEE: Most applicants for Youth Loans are dedicated and self-directed like Voiland. But Red Fire Farm, as his operation is called, might not have happened so early in his life without the initial support of the Rural Youth Loan Program.

VOILAND: I don’t know if I would have been able to grow my business as successfully or as quickly.

LEE: So it may be surprising that these loans are seemingly under-utilized in New England. Carrie Novak is chief of the Farm Loans Program for Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island. She says only five loans were made in these three states during the last fiscal year.

NOVAK: You could say it’s under-utilized. However, because a 10 to a 20 year old can borrow money legally under this program, this should be something that is really well thought out.

LEE: But Novak believes that restrictions which limit loans to individuals living in towns under 10,000 should be re-evaluated.

NOVAK: In the Northeast where we’re fairly high populated, we have a lot of kids that are interested in agriculture and would do some really good agricultural projects, but they live in a town of a higher population than 10,000. And I really would like someone to take a look at that and maybe up the population so that kids in a little bit more urban areas could be eligible for the program.

LEE: And according to director of loanmaking Jim Radentz, this will probably be a reality some time in the next year.

RADENTZ: Absolutely. We are looking at the population limit, and in fact, we do have plans to raise that from 10,000 to 50,000.

[SOUND OF POUNDING, ROOSTER CROWING]

LEE: Back at the farm, Josh’s father, Ron Sampson, is proud of his son’s desire to work on the land.

SAMPSON SR: Oh yeah. I’m really enthused about it, just for the appreciation for the land and working in the woods with the oxen. I hope he enjoys it and carries on with it. I’ll back him up, whatever he does.

[SOUND OF ROOSTER CORWING]

LEE: For Living on Earth, I’m Susannah Lee in Worthington, Massachusetts.

[SOUND OF ROOSTER CROWING]

[MUSIC: Zubot & Dawson, "Poor James," TRACTOR PARTS (Black Hen Records – 2001)]

Related link:

USDA Rural Youth Loan Page">

Malformed Frogs

CURWOOD: It’s been known for some time now that frogs are in trouble. They’ve been turning up with limb deformities and their populations are crashing worldwide. Studies point to culprits ranging from parasites to ultraviolet light to various forms of pollution. Now new research shows that atrazine, the most commonly used herbicide used in the U.S., might be playing a role. In a recent study, researchers found that up to 20 percent of male frogs raised in water containing low levels of atrazine developed abnormal reproductive organs. The researchers also found that adult male frogs had lower testosterone levels after exposure to the herbicide.

Tyrone Hayes, a professor of biology at the University of California at Berkley led the research and joins me now. Professor Hayes, what types of deformities did you find in these frogs?

HAYES: Well, we’ve shown that very low levels, very low doses of atrazine, will induce gonadal abnormalities. These include, in some cases, multiple testes— so you might have an animal with six distinct testes, but also, more dramatically, includes true hermaphrodites-- animals with both ovaries and testes. This might include an ovary one side, a testes on another, or two testes followed by two ovaries, or a mix of three testes and three ovaries all mixed up together.

CURWOOD: How do the amounts of atrazine that you used in your study compare with the amounts of atrazine that you find in America’s waterways?

HAYES: I think that’s what’s most shocking is we find effects starting at point one part per billion. And what’s shocking is that point one part per billion is incredibly low. Atrazine can be found in rainwater in Iowa-- it’s been reported at 40 parts per billion. It’s allowed in drinking water at three parts per billion. It can come off of cornfields as high as parts per million in the spring. So it’s an incredibly low dose, relative to how much atrazine is present in the environment.

CURWOOD: Well, wait a second. If atrazine is so prevalent, Professor, how can you conduct an experiment? How do you find unexposed frogs to compare with?

HAYES: [Laughs.] You know, that’s one of the problems. The animals that we’re working with in the laboratory, we use ultra-pure filtered water. So we know that the water, which we’ve also had tested in the lab, is atrazine-free. When we go into the field it does generate problems because there’s virtually no atrazine-free environment, although we can find localities that have atrazine levels below the level where we see effects.

CURWOOD: Professor Hayes, tell us, what exactly did you find in terms of a frog’s ability to produce offspring, given your concerns about atrazine?

HAYES: We have shown that in reproductively mature males, that atrazine eliminates testosterone. We’re now examining whether or not the animals will recover once they’re not exposed to atrazine. We’re also examining effects of, or the ability of, atrazine-treated males to fertilize and reproduce, but those data aren’t published yet.

CURWOOD: What kind of message does your research tell folks who are concerned about human health? If atrazine causes frogs to have lower testosterone levels, what kind of effects might it have on human testosterone production?

HAYES: You know, I want to say first, I’m not a human biologist or a mammalian biologist. I do know the mechanism is there. I mean, we make testosterone and estrogen the same way frogs do. My opinion is that in a whole organism, in a whole human, that there’s not enough atrazine would not likely accumulate to cause this problem because it’s not that soluble. If you drink atrazine, your kidneys filter it and you urinate it out.

What I don’t know, and what I would be concerned about, is how a fetus, which is effectively an aquatic organism, would respond to a high atrazine load. Perhaps people should focus on farm workers who are exposed to high levels of atrazine. And in particular, pregnant women who might be exposed to high levels of atrazine through occupation or just through the area that they live in.

CUWOOD: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has been working on a reassessment of the dangers of atrazine for some time now, and I guess they’re looking at as much science as they can find on the herbicide. Perhaps they’ll change regulations. What involvement have you had with this reassessment?

HAYES: I know that my published data have been available and we’ve also made available any other data that we’ve had. We’ve been very open, and I have been contacted by the EPA. So, you know, what impact it’ll have, I don’t know, but I know that it’s being taken into account as they make the assessment.

CURWOOD: As you stand back and look at your work, what’s the significance of this paper that you’ve just studied in the broad scheme of things?

HAYES: I think that the fact that these effects occur at such low doses, I think what it’s telling us is that we need to take a step back and look at how we evaluate safety. The animals, they don’t have cancer, they aren’t dying. If you look at them from the outside they look normal. It’s not until you get to the histological, to the microscopic analysis of the gonads that you realize that they’re not normal. And I think that of course, being able to produce crops and food in order to feed a growing human population is important, but also I think we have to take a close look at how that might have an impact on the environment.

CURWOOD: Tyrone Hayes is a biologist at U.C. Berkley. Thanks for joining us.

HAYES: Thank you very much for having me.

[MUSIC: Freezepop, "Freezepop Forever," FOREVER (Archenemy – 2000)]

Noise Map

CURWOOD: You’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: Over the next two years, scientists in the United Kingdom will be roaming the country listening for noise. As part of a European Union directive, they will map noise levels from the cliffs of Dover to the Shetland Islands and everything in-between. It’s all part of an effort to reduce noise pollution. John Hinton is one of the hundreds of noise specialists who will be gathering this data. He also led a project to create the first noise map of an entire city, his hometown of Birmingham, England. Mr. Hinton, welcome to Living on Earth.

HINTON: Hello, Steve.

CURWOOD: Tell me, how do you go about mapping noise? Are there people going to be out there with meters taking readings? How do you do it?

HINTON: It’s not so much people actually going out there and measuring the noise. It’s getting together all the data on traffic flows, traffic speeds, train movements, aircraft movements; perhaps some noise measurements around industrial sites. And then the software is used to calculate how that noise from the sources propagates throughout the city; tells you how bad the problems are in cities like Birmingham, and across the whole of the UK during this two year project.

CURWOOD: Well, how bad is the noise problem?

HINTON: Well, the European Commission have estimated that around 20 percent of the population of Europe are exposed to noise levels which are, they think, unacceptable. That’s noise that was above 65 decibels, and that equates to about 80 million people across Europe, which is a significant number of the population.

CURWOOD: If there had been a noise map made of the UK 40 years ago, how would it compare to today’s map?

HINTON: Well I think it would show that the noise levels from transportation sources were much less, even along the major roads that existed in those days. And there is a lot of concern that areas, so-called quiet areas of tranquility away from major cities are now being reduced because of this spread of transportation noise.

CURWOOD: I’m wondering what there is in the way of emerging technologies to deal with the problem of noise.

HINTON: Well, emerging technologies, there are things like low noise road surface. The UK government has an action plan to replace all the surfaces on truck roads — that’s the major roads across the UK-- with low noise road surface where that’s appropriate. Now it’s developing technology to produce low noise tars, as well, and pedestrianization of major cities is a good way of reducing traffic noise, providing you replace the private car with proper public transport.

CURWOOD: John Hinton is chair of the European Union’s Working Group on the Assessment of the Exposure to Noise, and a noise specialist in Birmingham, England. Thanks for taking this time with me today.

HINTON: Thanks very much for interviewing me, Steve. I’ve enjoyed it.

Department B/Animal Note

CURWOOD: Just ahead, some folks love them and others hate them. A California town battles over exotic eucalyptus trees. First, this Animal Note from Maggie Villiger.

[THEME MUSIC]

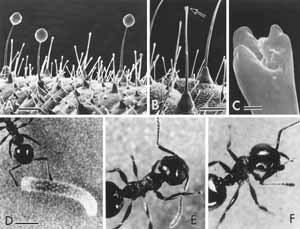

VILLIGER: The European cabbage butterfly is considered a pest here in North America where it likes to feast on vegetables like cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, and of course, cabbage. Scientists wondered what allows this species to gain such a strong foothold wherever it goes. The bug’s secret turns out to be a chemical defense system it produces in its larval stage. Rows of hairs run along the length of these caterpillars’ bodies. The tips of these hairs secrete a clear, oily fluid that collects in drops. In laboratory experiments, researchers watched as ants interacted with the cabbage butterfly caterpillars. As soon as an ant touched the caterpillar’s glistening hairs, it would back off and start frantically cleaning whichever body part had even brushed against the larva.

Caterpillars of the European cabbage butterfly, Peris rapae, (top image) are beset with glandular hairs, bearing droplets of a clear, oily secretion at their tips (image 2A). The tip of each hair is elaborately sculpted (images 2B & C), perhaps allowing the secretion to be held in place as the droplets build up. Ants keep their distance from the caterpillars, and spend a significant amount of time cleansing themselves after making contact with the caterpillar and its offensive secretions (images 2D, E & F).

For good measure, the ant would also clean the body part it had used to clean the initial point of contact. When the scientists isolated the irritating secretion they found a new group of chemicals they named mayolenes. These chemicals derive from a family of compounds that plants use to repel insect attacks. It looks like the European cabbage butterfly is such a successful invader thanks to its own shield of insect repellant. That’s this week’s Animal Note. I’m Maggie Villiger.

[THEME MUSIC OUT]

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Mellanova, "???," KNOW YOUR ENEMY (Archenemy – 2000)]

Eucalyptus

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. A debate over the fate of eucalyptus trees is dividing the town of Bolinas, in northern California. The Australian trees have been shading that charming seaside town for almost 100 years, but now an anti-eucalyptus contingent wants to fell the stately trees, saying they wreak havoc on native species. Despite that, there’s an opposing and ardent group of eucalyptus defenders. Louise Rafkin has our story:

[SOUND OF DRIVING]

RAFKIN: While driving on Highway One just north of San Francisco it would be easy to miss the turn-off for Bolinas. That’s partially because Bolinas residents— artists, surfers, and ecologists-- tear down road signs as soon as they’re posted. It’s this plucky separatism that gives Bolinas its flavor as an alternative enclave. So visitors in-the-know are told to turn off the highway after the lagoon and before the farmhouse, and then follow the line of towering eucalyptus trees to the end of the road.

But it’s these majestic trees, some rising hundreds of feet into the air, that are at the center of an ongoing battle between many of the 1,500 townspeople of Bolinas. The fast-growing eucalyptus are loved by some and hated by others, and those factions have been fighting over the trees now for years.

[SOUND OF CHAINSAW]

RAFKIN: Russ Riviere is a local tree cutter. He’s been busy felling the non-natives for dozens of Bolinas homeowners. An affable, bearded local, he loses his easy-going tone when he speaks of the Australian imports. He sees the eucalyptus as predatory, an invader that must be stopped.

[CHAINSAW OUT]

RIVIERE: We barely have the machines able to deal with it. I mean, just this year I took 120, 25 ton loads of eucalyptus wood off of this road and haven’t even dented it.

[SOUND OF WALKING]

RAFKIN: Riviere says the eucs, brought here in the late 1880’s for fuel and windbreaks, have all but choked out the native trees which support local animals and bird life.

REVIERE: Since we don’t have the enzymes, the bacteria, the fungus that break down the forest soil in Australia, we end up with huge sometimes seven feet, eight feet deep, four feet deep of just stuff— broken litter, branches, bark. It’s got shredding bark.

RAFKIN: The mounding debris is like a tinderbox, ready to explode in fire season, he says, and the clean-smelling camphor that floats off the trees is actually toxic to native plants

MOLYNEUX: For me, they somehow rather evoke the spirit of California.

RAFKIN: But artist Judy Molyneux, a strong supporter of the eucalyptus, has as much affection for the tree as Riviere has antipathy. She’s lived in the area over 30 years and was taken by the trees immediately when she moved to town.

MOLYNEUX: The way they moved in the wind, the sounds that the made, the way the light reflected and bounced off of them, their majesty. I have a love affair going with eucalyptus trees.

RAFKIN: Molyneux is part of a vocal contingent that has all but stopped eucalyptus cutting in Bolinas. There have been numerous boisterous meetings and the county recently got involved. Officials have already cited tree cutter Riviere for cutting without pulling a $1400 permit. But Molyneux says the support for eucalyptus trees is more than nostalgia. She cites the monarch butterflies as an important reason to keep the growth. The colorful monarchs sometimes over- winter in Bolinas. Studies are currently being done to see just how many monarchs use the groves. But while the jury is still out on whether the monarchs need the trees, the eucalyptus clearly have a negative effect on other natives.

[SOUND OF WALKING]

GEUPAL: Just poison oak and the little blackberries are the only species that really can handle the soils under eucalyptus. So again, the diversity here has gotten real poor. There’s no structural diversity, and birds can’t nest in it.

RAFKIN: Jeff Geupal is the scientist in charge of the Point Reyes Bird Observatory located just out of town. At nearby Jack’s Creek he points to a spot where the eucs have taken over the native bush. The creek-bed walls are denuded and caving in. Mud and tangled tree roots are all that show. Geupal says the trees have greatly upset the diversity of songbirds. Unlike their long-beaked cousins in Australia, California birds have short beaks. That means when they forage for insects in the eucalyptus, their beaks get blocked with the eucs’ gummy sap.

GEUPAL: This should be covered with yellow warblers and yellow throats. Even some of the shore birds might come up here because we’re so close to the ocean. When the tides are high they would use they would use the riparian. Again, this creek is more or less dead.

RAFKIN: Bolinas residents on both sides of the euc debate agree that emotions may have overrun the discussion.

[SOUND OF DOOR OPENING]

RAFKIN: Native plant activist and author Judy Lowry makes a living restoring people’s yards to their native state. Her own yard is covered in fragrant California mugwort and young oak saplings. In her garden there are birds and quail.

[SOUNDS OF BIRDS]

LOWRY: This is coyote bush. And this time of year, it’s pretty quiet, flower-wise.

RAFKIN: Lowry says the fighting among her neighbors has been bitter and ugly and that many harsh words have been said on both sides. But she says it’s one thing to restore a backyard to its native state. It’s very different to tackle the invasion of a whole town.

LOWRY: Since these eco-systems have never been disrupted to the point that they are now, there are no answers. But I feel that what I’ve seen in my garden has been really satisfying.

RAFKIN: Even pro-euc activist Molyneux knows the answer isn’t as simple as whether to cut or not to cut.

MOLYNEUX: I think the eucalyptus has become the scapegoat for the sense that, you know, we’re frustrated by the fact that we feel like we are damaging the environment.

RAFKIN: Meanwhile, as scientists continue to monitor the trees, birds, and butterflies, and the county continues to audit the number of eucalyptus felled, the townspeople of Bolinas keep one eye on each other and an ear cocked for the sound of chain saws.

[SOUND OF A CHAINSAW]

RAFKIN: For Living on Earth, I’m Louise Rafkin in Bolinas, California.

[SOUND OF A CHAINSAW]

Manatees

CURWOOD: We usually don’t think of altering an ecosystem as having environmental benefits. But that is the case sometimes with power plants in Florida. With the loss of natural warm water springs over the years, manatees have come to depend on the warm water discharge from power plants to get them through the cold winter months. Now, as these power plants update their technology, manatees stand to lose these warm water refuges, as well. Angela Swafford reports from Crystal River on Florida’s west coast.

[SOUND OF BOAT TOUR]

SWAFFORD: A small pontoon boat heads toward Crystal River National Wildlife Refuge, about 50 miles north of Tampa. Manatees congregate in large numbers here during the winter to swim in the warm and pristine springs that dot the area. Running deep under an insulating layer of rock, these springs bubble up in small tributaries of the river. Before reaching the area where the group hopes to swim with wild manatees, the tour operator makes sure everybody understands how to interact with the animals.

MARTY: Okay, guys, good morning. My name is Marty. I need to have your attention here for a couple of minutes. I really want to emphasize how important it is to be very, very quiet in the water with the manatee. Splashing sounds, moving your hands too much, moving your feet too much, splashing around, are going to scare them away. And sometimes, if you scare them away, they’re the only ones you’re going to find that day.

[SOUND OF CHAIN ANCHOR]

SWAFFORD: Spring water here surfaces at a constant 72 degrees. Manatees cannot tolerate temperatures under 68, so many of them are compelled to winter in these canals, swimming back and forth between the warm springs and the cooler gulf water where they feed on sea grass. More swimming and less to eat means each manatee will shed some 300 pounds by the end of the winter.

CHILD: We just saw one!

SWAFFORD: A few minutes after our arrival, a couple of manatees show up, much to the delight of the crowd.

WOMAN: Look, look over there, see it?

MAN: Here it goes, see? You can see the babies tail!

SWAFFORD: Like miniature Goodyear blimps, a 13 foot long adult and a younger, smaller companion swim underneath the pontoon.

WOMAN: I think they’re going away, yes.

SWAFFORD: Their brown backs are criss-crossed with pale scars, a testament to old encounters with boat propellers. But these manatees seem to know that as they get closer to this tour group, belly rubs and back scratches await them.

[SOUNDS OF WATER, PEOPLE TALKING]

SWAFFORD: The development of the area surrounding Florida’s waterways has caused a significant decrease in flow rates of the spring. As the soils are paved over, water can’t seep underground. What’s more, some of this water has been diverted for human use. There is even one plan to bottle it as designer water. Though some scientists fear that within the next decade there might not be enough warm water to keep these animals alive.

[SOUND OF POWER PLANT]

SWAFFORD: As natural springs deteriorate, man-made warm water refuges have become more important to the animals’ survival. Further south on Florida’s Atlantic coast, an electric power plant discharges tons of warm water every day into a shallow basin adjacent to the port of Palm Beach. Today, several manatees have congregated here, their dark backs bob in the water and their nostrils break the surface every so often. For the past 30 years manatees have become increasingly habituated to wintering at these discharges. Mothers even teach their calves to come to these areas.

[SOUND OF WALKING]

SWAFFORD: Winifred Perkins is manager of environmental relations for Florida Power and Light. She says on a given day as many as 500 can gather around a critical effluent.

PERKINS: But it’s not a perfect situation. Whenever you have a situation where a very endangered animal like a manatee depends on something like a power plant, you know, it’s sort of a two-edged sword.

SWAFFORD: This sword has already become apparent. Power companies are using more efficient methods to generate electricity, which means they are discharging cooler water. Also, there is a distinct possibility that within the next five years the power industry in Florida will be deregulated. If that happens, the effort to provide cheaper power may mean older, less efficient plants will be taken off line, further reducing the flow of warm water. There has already been a case in Jacksonville in which nine manatees died when they showed up at a power plant that had temporarily shut down operations.

PERKINS: And they just stayed there and stayed there and stayed there, thinking that the warm water would come back, and it didn’t. And the animal is so sensitive to the water temperature, if it gets too low, what they’ll do is they’ll forego eating, they’ll forego all sorts of things, and they’ll just work at trying to stay warm. And if that warm water isn’t there, they will ultimately perish, and that’s what happened in this case up in Jacksonville.

SWAFFORD: Even when warm water is flowing, manatees might still get into trouble. Some of these power plants are north of the manatees’ range, allowing them to winter where they would not normally be found. A Warm Water Task Force is looking at the downside of that, along with other issues. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service established a committee about a year ago. Composed of federal, state, and power plant officials, it studies the impact of industrial warm water discharges on manatees. With fully two-thirds of Florida’s manatee population dependent on 14 power plants, the location of each facility becomes critical. Jim Valade heads up the task force.

VALADE: We’re very concerned about these northernmost sites. There are sites in Titusville, over in the Cape Canaveral area, and we also have sites over in Tampa Bay area which are thought to be pretty far north for manatees. And at these sites—- for example, the one in Titusville-- we’ve got in excess of 400 animals that are wintering at that site.

SWAFFORD: The more northern the site, the farther the manatees will have to swim in the cold to reach their feeding grounds. This poses a particular danger for young manatees.

VALADE: They’re just not built to withstand cold weather temperatures. And if you have a fairly mild winter, you know, the animals do quite well. But we know from experience that if you have a severe winter where the temperatures plunge and it stays cold for a very long period of time— two, three, four weeks--well, then these animals are particularly vulnerable.

SWAFFORD: During the summer, the issue of warm water discharge takes on a new complication: thermal pollution.

VALADE: When you have warm water during the winter, it’s good for manatees. But manatees don’t use the plants during the summer, and so when the plants are discharging during the summer into these warm water areas that are naturally warm and you have this tremendous scouring effect, when you have these heated effluents discharging into the sea grass beds, you know, it has a tendency to destroy the grass beds.

[SOUND OF POWER PLANT]

SWAFFORD: Despite the drawbacks of the power plant discharges, officials recognize that manatees are dependent on them. So Florida Power and Light is trying to come up with ways to retool its aging facilities in such a way that manatees are kept warm in the winter and the grass beds are kept cool in the summer. Again, Winifred Perkins with Florida Power and Light:

PERKINS: At Fort Myers, we’re just in the process of re-powering a power plant over there, and part of our design for the new facility is quite interesting. We have put in a helper cooling tower that will cool the water in the summer, but we don’t plan to use that cooling tower in the winter because we want to still be able to provide warm water for the manatees.

SWAFFORD: There are other, as yet untested, ideas for keeping manatees warm. One calls for heating water with solar grids, another to dig pits in the underwater sediment to help the water retain heat in the winter.

[SOUND OF WATER SPLASHING, PEOPLE TALKING]

SWAFFORD: Back in Crystal River, the water gets progressively colder for the snorkelers who have been swimming since dawn, but they linger for a few last encounters with the manatees.

The Warm Water Task Force will continue to gather data and search for viable solutions. As Jim Valade with the Fish and Wildlife Services says, if this issue is screwed up, as he puts it, we stand to lose hundreds or even thousands of manatees. From Crystal River National Wildlife Refuge, I’m Angela Swafford for Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: John Zorn (performs Ennio Morricone), "The Sicilian Clan," NAKED CITY (Elektra/Nonesuch – 1989)]

Related link:

Manatees habitat">

CURWOOD: And for this week, that’s Living on Earth. Next week, when the suburb of Middletown, New Jersey lost 34 of its residents in the World Trade Center attacks, town-folk tried to put aside their squabbles and come together. But no one really knew just how hard it would be to do that.

WOMAN: I think some wonderful things came out of the horrible tragedy of September 11th. And in a horrible way, it did pull some people together. Hopefully, we can keep some of the good momentum going.

CURWOOD: The remaking of Middletown, next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC OUT]

[SOUNDS OF BIRDS, INSECTS, ANIMALS]

CURWOOD: Before we go, we leave you with the sounds of dawn in the Amazon forest, recorded by Jean Roche. He captured the howl of the howler monkey and the flute-like song of the musician wren.

[Jean C. Roche, "Awakening in the Amazon Jungle," DAWNS OF THE WORLD (EarthEar – 2002)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. Our production staff includes Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Cynthia Graber, Maggie Villiger, Jennifer Chu, Jessica Penney and Al Avery, along with Peter Shaw, Leah Brown, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson, and Milisa Muniz.

Special thanks to Ernie Silver. We had help from Rachel Girshick and Jessie Fenn. Allison Dean composed our themes. Environmental sound art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our technical director is Dennis Foley. Ingrid Lobett is our western editor. Diane Toomey is our science editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor, and Chris Ballman is the senior producer of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood, executive producer. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation, supporting efforts to better understand environmental change; the National Science Foundation, supporting environmental education; and the Educational Foundation of America, for reporting on energy and climate change.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth