January 24, 2003

Air Date: January 24, 2003

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

On My Honor

View the page for this story

Instead of signing on to the Kyoto Protocol, the Bush Administration has chosen to draft its own climate strategy. It’s a voluntary effort to curb greenhouse gas emissions by 2012, and senior administration officials have been asking major businesses to pledge allegiance to the plan. Host Steve Curwood talks with New York Times journalist Andrew Revkin about the scheme which is to be unveiled on February 6th. (05:00)

Enviro MBAs

/ Jesse HardmanView the page for this story

Since the early 90s, more than 50 graduate schools have offered environmental management classes or programs. The goals include showing companies that they can save money by being green. From member station WBEZ in Chicago, Jesse Hardman reports. (07:45)

Almanac/Up the Mountain

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about the first rope tow in the United States. Back in 1934, American skiers got a boost when the people of Woodstock, Vermont rigged a mechanical way to get to the top of the slopes. (01:30)

Ode to a Hot Dog Stand

/ Peter ThomsonView the page for this story

During its seventy year tenure, a hot dog stand in Oakland has become an anchor for residents of the city’s Temescal neighborhood in good times and bad. Producer Peter Thomson prepared our sound portrait of The Original Kaspers. (12:30)

News Follow-up

View the page for this story

New developments in stories we’ve been following recently. (03:00)

Emerging Science Note/Connect the Dots

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on a new way to see into the inner world of cells. (01:20)

World Legacy Awards

View the page for this story

Conservation International and National Geographic Traveler Magazine have announced the first World Legacy Awards. The winners are three destinations that represent the very best in eco-tourism. Host Steve Curwood talks with Costas Christ of Conservation International about what makes an eco-friendly vacation. (05:30)

Road Rules

/ Ky PlaskonView the page for this story

Off-road motor vehicle enthusiasts are cheering an Interior Department rule that might make it easier to drive vehicles on forgotten paths and roads on federal land. Wilderness advocates are worried. From member station KNPR in Las Vegas, Ky Plaskon reports. (10:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodREPORTERS: Jesse Hardman, Ky PlaskonGUESTS: Andrew Revkin, Costas ChristNOTES: Diane Toomey

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. President Bush calls on corporations to curb greenhouse gas emissions voluntarily. Meanwhile, in the nation’s business schools, there’s a growing trend to teach environmental science, along with marketing and finance. The lesson is there’s more than one way to go for the green.

KING: If they go work in a company, I don’t want them to advocate for less pollution because they think it’s moral. I want them to advocate for less pollution because in that case, in that company, given its circumstances, it’ll make money.

CURWOOD: Also, if you’re considering an eco-tour, the experts say stay away from Cancun. But you might want to consider the place being touted as the next big thing: West Africa’s Gabon.

MALE: You can see, for example, elephants walking on a beach. You can see hippos surfing in the waves. It’s really amazing.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth, right after this.

[NPR NEWSCAST}

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth’s coverage of emerging science comes from the National Science Foundation.

On My Honor

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I‘m Steve Curwood. Some of the biggest corporations in America are about to step forward and pledge allegiance to an alternative to the Kyoto Protocol that’s being promoted by the Bush administration.

On February 6th, major industry leaders will roll out their blueprint to comply with the president’s game plan to curb emissions linked to climate change. Meanwhile, senior administration officials have been traveling the country asking CEOs to promise in writing that their firms will meet the program’s goals.

The White House isn’t calling for a reduction of total greenhouse gas emissions. Rather, the plan calls for a voluntary 18 percent slowing of emission growth when compared to economic growth.

And joining me now to talk about this development is Andrew Revkin, who covers the environment for The New York Times. Welcome Andy.

REVKIN: It’s good to be here.

CURWOOD: Andy, let’s talk about exactly what the administration is asking these companies to do. What are they expecting in terms of written promises and what promises have they extracted so far?

REVKIN: The administration is looking for something it can show the country that says that the country is on this trajectory that the president spoke about a year ago. He said the nation should, in a voluntary way, act to curtail emissions so that ten years from last year, 2012, the rate of growth will be 18 percent lower than it was last year.

So then, what they did was they parsed out industry. They said, okay, we’ve got autos here, we’ve got oil here, we’ve got electric generation here. And they started going around to these sectors and saying, look, what can you do to help us prove that the administration’s goal was achievable?

And there was a back and forth thing on this. For example, the American Petroleum Institute, which represents all the big oil producers-- Exxon and Shell, BP-- at first, wrote a letter to the White House saying we would like to commit to this general goal of heading in the right direction. That kind of thing, sort of nonspecific. And the administration said, that ain’t going to cut it. They literally said, nah, try again. If you want to stand with us on the podium next month and talk about goals, they have to be real goals: concrete, measurable, tonnage of gases. Not some vague commitment to “I pledge allegiance to the atmosphere,” that kind of thing.

And that’s basically been the same with each of the sectors. The American Chemistry Council, the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers, they’ve all had to kind of come up with a number which is realistic, which they feel they can actually do and that the White House sees as sufficient to make its case.

CURWOOD: Andy, tell me, what’s the incentive for business to sign on to this? And they can’t participate in international carbon trading because the United States isn’t part of the Kyoto Accord. What’s in it for business to agree to making written promises to reduce their emissions of greenhouse gases?

REVKIN: Well, there’s a couple of benefits to signing in for your industry. One is they’re hoping to ward off or fend off the possibility of actual legislation or other changes in regulations that would require cuts. And so many people in industry have decided that the best way to do that is to at least try to prove that volunteerism can work.

And that’s been the administration’s approach, too. Right now if they can’t show that industry is willing to sort of get on board for these kinds of efforts voluntarily, then that would add ammunition to folks who are trying to pass laws that would restrict them. John McCain and Lieberman from Connecticut just two weeks ago rolled out a proposed bill from both sides, Republican and Democrat, saying it’s time for a countrywide approach to slowing, to actually reducing, gas emissions. And that’s the kind of thing the industrial sector really doesn’t want to see yet.

CURWOOD: How much is this going to help the White House politically, at home and abroad, do you think?

REVKIN: They have a conservative base that they need to satisfy to win states like West Virginia, which sits on a heap of coal, and Ohio. At the same time, though, their polling has shown suburban educated middle-class women, sort of the classic soccer mom, for that person climate change has become a dominant environmental issue. It’s no longer the local toxic waste dump or sprawl, it’s climate change. And the Bush administration seems to feel it needs to do something to keep those voters in the tent, along with their base, which is, you know, in states like West Virginia.

CURWOOD: If this is a voluntary program, how would the administration follow up on these promises that they’re getting from industry?

REVKIN: That’s still very fuzzy at this point. It’s not contractual volunteerism. People can opt out. And from what I understand, the main sort of hazard in opting out is just adverse public publicity. So, that’s about it as far as the end game. And of course, one of the paradoxes that some people have pointed out in the president’s overall approach is that he’s talking about a timeline that ends in 2012. And that’s significantly beyond his term in office, even should he be re-elected. So, it would be up to someone else to determine whether this worked or not, long after George Bush is back on the ranch or somewhere else.

CURWOOD: Andrew Revkin covers the environment for The New York Times. Thanks for taking this time with me today.

REVKIN: It’s great to be here.

Enviro MBAs

CURWOOD: If you want to learn more about environmental science, these days a good place to study may well be a graduate school of business.

Historically, MBA programs and the companies they supply with managers have been skeptical of so-called green economics and business. But, more and more, that’s changing. A combination of regulations, public concerns, and a profit motive have spawned a number of MBA ecology programs over the past decade, with varying degrees of success.

From member station WBEZ in Chicago, Jesse Hardman reports.

HARDMAN: The recent transatlantic business dialogue in Chicago brought CEOs and governmental officials from the U.S. and Europe together. In response, protestors took to the streets to raise issues of sustainability, corporate greed, and the environment.

[DRUMMING]

FEMALE: Cover the issues. Cover the truth.

[CHEERING, APPLAUSE]

FEMALE: Cover the issues. Cover the issues. Cover the truth.

HARDMAN: The small but boisterous crowd was largely made up of young twenty-somethings.

[CLASSROOM SOUND]

HARDMAN: But just down the block from where the protest began, Michael Lewis, Anjana Famis, and Brian Vickens sit in a classroom. As students at Illinois Institute of Technology’s Stuart School of Business, the environment is the backbone of their studies.

MALE AT BOARD MEETING: It’s a little bit beyond risk assessment and management. I’m afraid that course would get more off on risk assessment because it’s more interesting to teach.

HARDMAN: At IIT’s environmental management program biannual board meeting, Lewis, Famis, and Vickens are presenting work-related projects they’ve been developing at school.

LEWIS: So, the process that we did was to take this Elmo, cut it open, separate it into its various parts by material, various plastics...

HARDMAN: Michael Lewis has dissected a Tickle-Me-Elmo doll for his project. The goal is to find out how Mattel Corporation, Elmo’s makers, could do a better job of not only using recycled materials, but less materials to make their product.

LEWIS: Looking at each one of these materials from its whole life cycle, the metal that needs to be mined and then reduced to its ore, formed into the screws. The amount of labor that goes into putting it into the actual product itself...

HARDMAN: Lewis has written up a cost analysis plan to show how Mattel could save money by creating a more eco-friendly Elmo.

LEWIS: I feel that environmental management is a good way, when combined at the business level, that these can be quantified and people can see what these benefits are. And, hopefully, eventually realize some increased profits over that, as well as decreased environmental impacts. That’s a lot to get out of Elmo, but... [laughter] ...that’s where we’re at.

HARDMAN: Programs like IIT’s began popping up across the country ten years ago. According to the World Resources Institute, a Washington D.C.-based environmental think tank, there are around 50 graduate schools in the United States with either full-fledged MBA programs or classes in environmental management.

Mike Russo teaches an environmental management course at the University of Oregon’s Lundquist College of Business. Russo says over the past ten years there has been a big change in corporate mentality.

RUSSO: Businesses that are wise understand that environmental stewardship can be very consistent with the bottom line, in that companies that ignore environmental imperatives do so at the risk of their business.

HARDMAN: Russo co-authored a study that showed that firms with high environmental standards make a bigger profit than firms without strict standards. He says that evidence has helped convince MBA students of the importance of environmental knowledge.

RUSSO: They realize that for one to advance in a business career, that, just as one’s career would be held back if one didn’t have a working knowledge of, say, accounting in a traditional sense, one’s career could conceivably be held back if, as a rising professional, they didn’t appreciate the costs and benefits of decisions that they make that have environmental ramifications.

HARDMAN: But Russo’s views are not shared by all. Andy King is a management professor at Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business. King says many schools have struggled to maintain programs and classes in environmental management. MBA programs that incorporate environmental study do so in a variety of ways, including elective courses, concentrations, and even dual Master’s degrees in business and environmental studies.

King says at top MBA programs, like Dartmouth, Michigan and NYU, despite interest, students are sometimes pressured not to take environmental classes.

KING: When a student goes to a program that involves multiple years, and involves perhaps one year in an environmental science program, they don’t always see that as valuable. And they’re spending, you know, $30-50,000 dollars a year on a business school education, their opportunity cost is a $150,000 dollar job out there, and that $200,000 swing for that extra year doesn’t seem like it’s worth it.

HARDMAN: King also says environmental programs are still viewed as new and controversial by many old-school MBA faculty. He says many environmental management professors hurt their own case by teaching the environment as an advocacy issue. King says for now the best way for programs to attract support, and ultimately students, is to stick to business.

KING: If they go work in a company, I don’t want them to advocate for less pollution because they think it’s moral. I want them to advocate for less pollution because in that case, in that company, given its circumstances, it’ll make money. And I think if you lead with the ethical, I think it’s a much weaker case. I think it’s better to say here are some opportunities where you can make money and do something that’s good for the world, and oh, by the way, isn’t that ethical?

HARDMAN: King says he does think environmental management programs are primed for a breakthrough in the near future. John Challenger, president of Challenger, Gray and Christmas, the nation’s oldest corporate recruiting firm, agrees. Challenger says companies are undergoing a major ideological shift in what they want from MBA students.

CHALLENGER: Hopefully, it’s changed in the wake of the Enron scandals, the Anderson problems, 9/11. Companies are looking for students with higher integrity, with ethics, with character, rather than just for people who are going to push the bottom line.

MALE AT BOARD MEETING: One of the things that you probably haven’t had a chance...

HARDMAN: Back at the Illinois Institute of Technology board meeting, discussions continue on how to improve the environmental management program. School officials say, in addition to regular classes, they’re planning a series of workshops and seminars this year for business leaders. But for the most part, they’re banking on students like Anjana Famis to put their program on the map.

FAMIS: We’re almost kind of the new leaders in companies trying to emphasize the environmental and socially responsible issues more than they traditionally would. So I think they want you to be as smart and as knowledgeable as possible. I think it’s a growing field, a growing industry, and the more you know, the more powerful you're going to be.

HARDMAN: And Famis says as she and her classmates enter the workplace, they’re hoping to convince a business world just starting to get to know them that it can’t live without them.

For Living on Earth, I’m Jesse Hardman in Chicago.

CURWOOD: Just ahead, that special sense of neighborhood that comes with relish and a bun.

You’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Alison Brown “Tbe Red Earth” A World Instrumental Collection Putumayo World Music (1996)]

Almanac/Up the Mountain

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living On Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: Edison Records “Flirting on the Beach” The Black Wax Sampler, 1996 www.tinfoil.com]

CURWOOD: Sixty-nine years ago, downhill skiing in America could be a sweaty proposition. That’s because back in the good old days there was a significant uphill component to the sport. Skiers had to hike up the mountain carrying their skis before they could shoosh back down the slopes. But in January 1934, everything changed when the people of Woodstock, Vermont rigged up the first American rope tow. At the base of a hill in a farmer’s pasture, they jacked up a Model T Ford truck, attached a long loop of rope around one of the rear wheels. Then they snaked the rope up the slope, supported by tripods and pulleys. When the ready signal was given, somebody would sit in the driver’s seat and step on the gas, causing the wheel to spin and the rope to be pulled up the hill, skiers in tow.

(Photo courtesy of Sherman Howe)

Word of the new rope tow spread fast and, almost overnight, Woodstock became a mecca for New England skiers. The first year, a dollar would buy you all the rides you could fit into a day. And you might even catch some air going uphill, particularly when a mischievous tow operator would push the pedal to the metal and send the rope tow a’flying at speeds of up to 60 miles an hour.

And for this week, that’s the Living on Earth almanac.

[MUSIC FADES]

Ode to a Hot Dog Stand

CURWOOD: Think about that special spot you remember from your hometown. Maybe it was a store or a restaurant or a playground. That spot where you felt, “this is my town, my place, my home.” Chances are there was a unique name over the door and a unique character behind the counter or concession stand.

And in some corners of America, these quirky old businesses still survive. One of these is a little scrap of a place in the neighborhood of Temescal, in Oakland, California. It’s called Original Kasper’s Hot Dogs, and for more than 70 years it’s served up a sense of community along with ketchup and onions. Producer Peter Thomson has this sound portrait.

YAGLIJIAN : Hey, how are you doing today?

MALE: Man, I’m ...(inaudible). I need a hot dog.

YAGLIJIAN: Okay, one original coming right up.

{KA-CHING!]

MALE: I love Kasper dogs, and they do something a little different to spice it. I think ...(inaudible)

YAGLIJIAN: It’s just amazing what a simple little item like this hot dog, the kind of joy that it brings to people.

FEMALE: It’s more than just a hot dog. It’s the feeling that they make you feel when you come here. It’s like home.

MALE: Oh my god, I’ve been coming here since before Harry was born. [laughs] Keeps me going.

[KA-CHING, KA-CHING!]]

YAGLIJIAN: My name is Harry Yaglijian, I operate Original Kasper’s Hot Dogs, the original Kasper’s at 45th and Telegraph, right where Shattuck and Telegraph meet here in Oakland, California. And we were founded in 1929 by my grandfather, Kasper Kajulian. And this business was run by my father for over 50 years, between 1947 and 1997, at which point I took over managing the business.

[KA-CHING, KA-CHING]

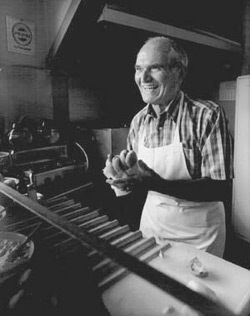

The late Henry Yaglijian.

(Photo: Emilio Mercado)

MALE: I have an aunt who used to live here in Oakland. She’s 88 years old. She lives in Los Angeles. If I get the hot dog before I fly down, she’ll eat it when I get off the plane. And whenever she comes here, this is her first stop, Kasper’s. She’s coming up in May.

YAGLIJIAN: Oh is that right?

MALE: Yeah. I think this is why she’s coming. She’s not coming to see us. [laughs] She's hungry for a hot dog. That’s all she talks about.

[KA-CHING]

MALE: A little over 30 years ago when I first came here somebody said, if you want to get a good hot dog, there’s a place called Kasper’s where Telegraph and Shattuck meet. And I said, Telegraph and Shattuck don’t meet, they’re parallel to each other. And they said, no, they meet and there’s this very peculiar little triangular building at the intersection. And sure enough, they were right. You have to almost smile looking at the building because who would build a building like this? [laughs] It’s like two feet wide at one end and not much wider at the other, like a miniature flatiron building.

MALE: The first thing I noticed about Kasper’s when I moved here was the building itself, this really tiny, odd-shaped, almost ramshackle-- it’s a very unusual building. And the feeling was that it had been there for an awful long time.

[KA-CHING]

MALE: Let me have five.

YAGLIJIAN: Five? All for you? The record is nine, you know. I saw a woman eat seven of them.

YAGLIJIAN: I was mentioning to a customer this morning who asked about how many hot dogs my father sold in the 50 years that he worked here. And I calculated it out to be somewhere between four and a half and five million hot dogs.

[KA-CHING]

YAGLIJIAN: There’s a way to make a hot dog, at least the style of hot dog that we make. And they have to go together in a particular way, just so everything kind of works together. This is what I try to teach the people that work for me and this is what was taught to me by my dad. He would say, no, cut the onion like this, or slice the tomatoes this way because they fit in the hot dog better.

So many times when people see on our hot dog board anywhere from two to ten hot dogs being prepared, they’ll go, this is a work of art. It is art.

[KA-CHING, KA-CHING]

YAGLIJIAN: Before my dad came into the hot dog business he was a gem cutter, a lapidarist, actually, I think is the proper term. And he cut precious and semiprecious stones for a company in Los Angeles named Kazanjian Brothers Jewelers. I don’t think the hot dog business was something he would have chosen for himself. I mean, he was doing something that he really enjoyed doing, he loved, and that he was very, very good at. You know, after my mom and dad married, I can only imagine that my grandmother, who was left with this business, was having a very difficult time, and probably put a lot of pressure on my mom to come back and help her. So he left the gem-cutting business in LA and moved my mom and-- who was pregnant with me at the time-- back up here to Oakland to keep harmony in the family.

But after he made the decision to get into the hot dog business, he really did commit himself to it. And he loved the people that came in here and he loved his little-- he called this his “little place” and he loved it.

[KA-CHING]

MALE: (MUNCHING} Thank God for Kasper’s. I save my hot dog credits for this place mostly, or an A’s game. It’s so much better around here now, again. It seemed like it got really funky for a while there, like 10, 15 years ago or something. People moving out, other people either not moving in or not improving, and then a lot of drugs, I think. And this wasn’t the worst, by far, but I just think it affected Oakland heavily. I think it just sapped a lot of the spirit and the money and everything, the will.

[KA-CHING]

MALE: Oakland was a haven for the gangs and the drugs. And I had said that I would never live in Oakland again, and I joined the military.

MALE: The economic decline, on Telegraph Avenue anyway, began in the late ‘50s through the ‘60s, when the freeway was being built. There were hundreds of houses removed. There were many, many businesses that were demolished. So, a lot of people moved away.

YAGLIJIAN: As the demographics of the neighborhood changed, the businesses that were traditionally relying upon the neighborhood base started to experience decline. And this is especially true of the ethnic businesses. The predominantly Italian nature of the neighborhood meant that there were many businesses here that catered to the Italian culture. And when the clientele left, they just couldn’t hold on.

MALE: The average business would have probably moved a long time ago from the strife that this place has had. But, to show his determination to stay and the belief in the community, he’s here. He’s here and he’s not going.

YAGLIJIAN: Over the 50 years that my dad worked this business, he was held up almost 40 times. Working alone in a little store like this, through some of the rough times that this neighborhood has experienced, was no picnic. But, on the other hand, it’s also one of the reasons why my father gained so much respect from the people that lived here for so long. Because he hung in there, just like they did.

[KA-CHING, KA-CHING]

MALE: It’s like a neighborhood anchor.

MALE: I refer to it as the anchor of Temescal.

MALE: This is home.

MALE: It’s a haunt, you know, it’s a neighborhood thing. It’s good because I got some really bad stuff going on right now and it’s good to be able to depend on something. I depend on Kasper’s for that. It’s real good that it’s here. Real good.. [laughs]

[KA-CHING]

YAGLIJIAN: I was just going to ask, Brad, do you want your lemon chicken dog the lemon chicken dog way, or the Kasper way?

BRAD: Which--the Kasper’s way with the cheese and stuff, right? No, no, no. I want it your way.

YAGLIJIAN: Italian parsley--

BRAD: Yeah, all that, and then two Kasper’s to go. I used to go to high school up the street and I’ve been coming here since then. This was the place to go after school. Kasper’s makes it in front of McDonald’s, what is this, Jack in the Box. No matter what they throw at it, it’s still here. It’ll be here after they leave.

YAGLIJIAN: The original Kasper’s is a place that people--it’s a place that if it were not there, people would find there would be a hole in their lives. As far as my part in it, it’s, I mean, I’ve struggled with my part in it, to be honest with you. But I stay with it because it’s something that’s so much a part of the history of my family, the history of this place, Oakland and the Temescal area. So much a part of so many other people’s lives, that I just can’t ever imagine it closing. I’m not going to say that I don’t want to do other things, but Kasper’s is a place that will always be there because it’s a place that always has to be there.

[KA-CHING, THEN, KIDS SHOUTING]

YAGLIJIAN: Here come the kids. It’s candy time.

[KIDS SHOUTING]

BOY: Kasper got some good hot dogs.

GIRL: They’re nice people because when we come in, they let us stay in when it’s raining and stuff. And they--if we don’t have enough money--they let us pay them back and stuff. So I like Kasper’s a lot.

BOY: They got hot dogs about that big, like a ruler.

[KIDS LAUGHING]

GIRL: You know how most people, like, when they see a whole bunch of black kids they be wanting to try to kick us out, talking about only two at a time. And they let us all go in there.

GIRL: Sometimes they give us free food. Sometimes, but not all the time.

GIRL: I’m sorry that a long time ago, like 2000, the person that owned this place, he had died. And his son has taken over, and a couple friends.

BOY: How did he die, though? How did he die?

YAGLIJIAN: You do want this spicy, right, young lady?

FEMALE: Yes, please.

BOY: You gonna have a hot dog?

MALE: I had one for lunch.

BOY: Oh, you did?

MALE: Yeah.

BOY: How did it taste?

MALE: Delicious. Have you had one?

BOY: No. I want to try one though. I ain’t got enough money, so…[sighs] One of these days. I want to ask him if I can get a free hot dog. Can I get a free hot dog?

BOY: Thanks.

YAGLIJIAN: You’re welcome. Do me a favor: don’t tell your friends. There’ll be a line over here asking for free hot dogs all day long.

BOY: What?

MALE: How’s that dog?

BOY: [Smack, smack] Excellent.

[LKA-CHING, KA-CHING]

YAGLIJIAN: So, here’s one original, coming right up. I’m taking a nice, freshly-steamed bun, put a little bit of mustard in the bottom of it. There we go with the hot dog in the bun, and now we’re going to put a little relish on. A little more mustard on top, and then I’ll slice the onions. An Original Kasper’s hot dog always has sliced onions on it, so--although we’ll chop your onions for you if you really have to have it that way.

So, now I’ve made three slices of onions and I’ve put them on one side of the hot dog. I’ve sliced three little wedges of tomato and I’m putting them on the other side of the hot dog. A dash of salt. A dash of our special combo pepper. Di lo papidi, as one of my gypsy customers calls it. And there we have an Original Kasper’s hot dog. Mustard, tomato, sweet relish and onions, sliced onions. And that’s how we’ve done it since 1929.

So, your total is $3.98 altogether…out of five. This makes four and the one makes five, and thank you very much, have a wonderful day. Take care.

FEMALE: Thank you.

CURWOOD: Our portrait of Original Kasper’s Hot Dogs was produced by Peter Thomson.

And if your mouth is watering for a Kasper’s dog just about now, well, you’ll just have to wait a few weeks. Owner Harry Yaglijian tells us he’s closing the Original Kasper’s for its first major renovations in 60 years. Harry hopes to be serving up his dogs again in March.

[MUSIC: Davi Hewitt “Streetbeat” A World Instrumental Collection, Putumayo World Music (1996)]

CURWOOD: You’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include the Oak Foundation, supporting coverage of marine issues, and the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation.

[MUSIC]

News Follow-up

CURWOOD: Time now to follow up on some of the news stories we’ve been tracking lately.

The cities of Arcata and Oakland, California have joined the city of Boulder, Colorado in the global warming lawsuit against two federal agencies. The complaint alleges that the government’s Export/Import Bank and the Overseas Private Investment Corporation finance energy projects abroad without assessing their impact on the U.S. environment, as called for by the National Environmental Policy Act. Oakland Mayor Jerry Brown explains why his city signed on.

BROWN: We want clean air. We don’t want greenhouse gasses, and we also don’t want sea levels rising, because we’re a coastal city. Or climate disruption.

CURWOOD: Co-plaintiffs in the case include the activist groups Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace. The Bush administration has filed a request to move the case from San Francisco to Washington D.C.

[MUSIC BUTTON]

CURWOOD: The final rounds of U.S. Navy live fire training exercises on the Puerto Rican island of Vieques are underway. By May 1st of this year, the Navy says it will leave the island for good. Navy Ensign David Luckett says the evacuation will pay attention to the environment that will be left behind.

LUCKETT: Basically, we’re going to go ahead and follow the previously established standards in the turnover process. We’re going to protect and conserve the natural environment, visually inspect and perform surface clearance based on historic use and records of the training conducted there.

CURWOOD: Ensign Luckett says the Navy will relocate its training exercises to already existing sights in Florida and North Carolina.

[MUSIC BUTTON]

CURWOOD: Local authorities have removed the suburban tree sitter from his perch in a centuries-old valley oak in Santa Clarita, California after 71 days. John Quigley chained himself high in a tree known as Old Glory to protect it form developers. Even though he’s back on the ground, he says the fate of the tree is not yet sealed.

QUIGLEY: Our main focus is to get the issue of Old Glory onto the agenda for the full board of county supervisors. We believe if we can do that and have a public hearing on all of the options, that we have a chance to save the tree where it is.

CURWOOD: Some want a new road to go around the tree so it doesn’t need to be uprooted and relocated, a move they don’t think the tree would survive as it is 70 feet tall and 16 feet around.

[MUSIC BUTTON]

CURWOOD: Ever wonder at the amazing regularity of Old Faithful? Proctor and Gamble would have you thanking the company’s laxative, Metamucil. A new TV ad shows a park ranger giving the punctual geyser its daily dose. The tongue-in-cheek spot is eliciting an outpouring of indignation that took Proctor and Gamble by surprise. A spokesman said, clearly ,when you try humor, not everybody gets it.

And that’s this week’s follow-up on the news from Living on Earth.

[MUSIC UP]

Emerging Science Note/Connect the Dots

CURWOOD: Just ahead, honoring the best in eco-tourism. First, this Note on Emerging Science from Diane Toomey

[THEME MUSIC]

TOOMEY: When scientists want to view the intricacies of the cellular world, they tag proteins in cells with fluorescent organic dyes. But the field of biological imaging may soon be revolutionized by cutting-edge nanotechnology. Quantum dots are tiny light-emitting crystals made up of semiconductor material that fluoresce when a light shines on them. Unlike dyes, dots can be made to shine in virtually any color, just by altering their size. So dot technology should allow many more objects to be tracked simultaneously. And quantum dots are brighter and can last up to 1,000 times longer than dyes.

Now, two separate research teams at the Rockefeller University have, for the first time, demonstrated that quantum dot technology can be used in living cells. One team injected a billion of these dots into a frog embryo. Embryonic cells are normally opaque, but under the light of quantum dots, their nuclei became visible. Researchers were able to trace the dots as the cells divided into the tadpole stage.

The second group of scientists tricked slime mold cells into gobbling up some quantum dots and were then able to watch these single-celled creatures interact with each other.

That’s this week’s Note on Emerging Science. I’m Diane Toomey.

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: David Hewitt “Streetbeat” A World Instrumental Collection, Putumayo World Music (1996)]

Related links:

- Frog embryo press release and video

- Slime mold press release and video

World Legacy Awards

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

If you’re looking to beat the winter blues with a quick vacation, consider this: folks at Conservation International and National Geographic Traveler Magazine have found some green getaways while scouring the globe for the most environmentally responsible tourist experiences. And after sampling a variety of these eco-vacations, they recently gave three destinations the first World Legacy Awards. A wilderness safari in South Africa, a village home-stay program in Thailand, and a walking tour on paths dating back to the fifth century in Italy got top billing for being environmentally and socially responsible destinations.

Costas Christ is senior director of Conservation International’s eco-tourism department. Mr. Christ, so those are the best environmental tourist experiences on the planet. But what about the worst?

CHRIST: I have great concerns about the development of Cancun. To me, what has happened in Cancun has been, in many respects, quite tragic, both for indigenous people who used to inhabit this area as well as for the environment, in which we’ve seen tremendous devastation to endemic plants and wildlife in the Cancun area. Although we have a winner in the country of Thailand, a very deserving winner for incredible work they’re doing, there’s another place in Southern Thailand, just south of Bangkok, terribly over-developed with devastating impact on the environment, as well.

CURWOOD: Your organization used scientists, anthropologists and tourism professionals to help you make these judgments, but how does the average tourist tell if a vacation spot is environmentally responsible? What are some of the signs to look for?

CHRIST: Number one, I would look for a company that not only has expertise in that area, but whose operating philosophy is one of, say, care for the earth, care for the people, care for the environment around it. How do you see that? Well, are they employing local people, for one? Are their guides representative of the local culture in the area you’re visiting? On a safari to Africa, I would love to learn about Africa from an African guide more so than I would by a knowledgeable American. I would ask do they buy their fruits, their vegetables, their foods, their materials, their vehicles, whatever it might be, in a way that supports and benefits the local economy most directly? And I would also want to know how do they invest in conservation of the particular area, whether that’s a historical monument, or whether that’s rare wildlife?

CURWOOD: What’s the next eco-tourism hotspot that you see developing?

CHRIST: I think that Belize continues to get attention. I think that not only Belize as a country but the five Central American countries that hold the heritage of the Mayan world, and also have some of the world’s most pristine wilderness areas and very rich in biodiversity. Those would be southern Mexico and Guatemala and Belize, El Salvador and Honduras. I think that, politics aside, the Philippines, the island of Northern Palawan is an area of great interest and spectacular beauty and rich cultural heritage as well. There’s a project there that’s underway to try and develop Palawan into the world’s first sustainable tourism resort.

An area that has tremendous potential that I think few, if any, people have heard of is the country of Gabon in western Africa. Absolutely mind-boggling in terms of its, you know, very, very rich wilderness heritage and the last stronghold, for example, of lowland gorillas on the African continent. The only place that I know of in Africa where you can see, for example, elephants walking on a beach. You can see hippos surfing in the waves. It’s really amazing what Gabon has to offer. And we’re doing some work there, as well, to help that government develop its interest in tourism for economic gain, but to do so in a way that will help protect what makes Gabon special today.

CURWOOD: Tell me, is eco-tourism the same as environmentally responsible tourism?

CHRIST: It is a common misunderstanding to confuse eco-tourism and nature tourism. They are not the same thing. You and I could go on a wonderful jungle-rafting trip tomorrow in Costa Rica and we could have the greatest time, enjoy it, eat good food, look at the stars, see the birds, and come home and say, boy that was a nice vacation. But it was just a nature travel experience unless that trip contributed to the conservation of the area we visited, and helped to sustain the well-being of the local people in that area. That’s what makes it eco-tourism.

It’s easy for places to promote themselves, but as travelers become more aware that their choice does make a difference, and they begin to ask more discerning questions, and it becomes more and more easy to see those who are trying to present themselves as eco-friendly from those who are really doing the hard work to make it a reality.

CURWOOD: Costas Christ is senior director of Conservation International’s eco-tourism department. Thanks for taking this time today.

CHRIST: Thank you very much for having me.

Road Rules

CURWOOD: The number of four-wheel all-terrain vehicles in the back country is skyrocketing, and riders are forming a new and powerful recreational lobby. ATV enthusiasts are cheering a recent Bush administration rule that makes it easier for local governments to claim control of trails and old roads on federal lands. Wilderness advocates are worried the change will mean widening and even paving trails in national parks and forests.

From member station KNPR in Las Vegas, Ky Plaskon repots.

PLASKON: The Valley of Fire has always been a popular place. The black petroglyphs Indians drew here 2,000 years ago still adorn the valley’s blood-red walls. The Indians are gone now but locals have loved riding their ATVs here for a long time. Recently, that was made legal.

[ENGINE STARTING]

PLASKON: Stony Ward, owner of ATV Adventures, is getting ready to guide customers around a cluster of desert trails here, about 60 miles north of Las Vegas. He advertises that you can see the petroglyphs while riding at great speeds over pink coral sand dunes, through dry river beds, and past red sandstone canyon walls.

WARD: We change people’s lives. We have a lot of people that’s been behind a desk, or from New York, that’s never even been in the desert. And they get out here and 90 percent of the people have never ridden before. And they get out here and they turn into like, oh, I can’t believe the peace, the quietness, the thrill of riding the ATV. It’s just--we’ve actually changed a lot of people’s lives. They actually go a different direction when they get back and say, you know what? I’m going to go out and do outdoor activities a lot more.

PLASKON: Ward says a lot of people go home after his tour and buy ATVs, the squat four-wheel vehicles with bulbous knobby tires and bike handlebars. They cost $2-7,000 dollars. The sport gained popularity in the late 1980s but by 2001 sales hit a million. That’s selling 3,000 ATVs and motorcycles each day. People are driving these motorized vehicles on paths in national forests, in parks, across deserts, and federal range lands. Millions of acres are now criss-crossed with tire tracks.

The users also ride on vacant lots in cities, creating dust problems. In the wilderness, they make a lot of noise, destroy vegetation, threaten animals, and leave a lot of trash. Over the last year, ATV owners discarded more than 15 tons of trash across one of the most popular off-road areas in the nation, the Glamis Dunes in southeastern California, though some riders recently organized a huge cleanup. Industry supporters say the important thing is that ATVs are encouraging more people to use public lands.

[MACHINE SOUND]

PLASKON: At the Valley of Fire, volunteer Tom Dickinson runs a generator and drives screws into a sun shelter, the kind of amenity people appreciate in the shadeless desert. They’ve already built public restrooms. Nearby, someone dumped some old couches after a party. One of the biggest criticisms is that bikers and ATV riders don’t stay on roads or even paths, but cut through wild country, destroying fragile soil. Dickinson concedes that’s true.

DICKINSON: You will have one person that’ll go off, and then another person will go behind him and see trails--a trail going off, thinking, that it’s a trail. And that’s how these other trails get started. That’s tough to say, you know, stay on the highway and drive in your lane, don’t go off road. That’s a tough one, you know.

PLASKON: Valley of Fire off-roaders like Dickinson and Ward agree that before more ATV roads are added there should be more signs and people should be taught about the damage caused by cutting new paths. But 11-year-old Alex Hicks, who started riding when he was six, says no one has ever told him to stay on the trail.

PLASKON TO HICKS: Do you ever go off the trail?

HICKS: Sometimes.

PLASKON: Why?

HICKS: Just to see what else there is out there, to ride around with.

PLASKON: Is that okay, do you think?

HICKS: Yeah.

PLASKON: Why?

HICKS: I don’t know. Just to go see if there’s bigger hills or stuff.

[ATV STARTING AND DRIVING AWAY]

PLASKON: He says it’s okay to ride off-trail, as long as you don’t tear it up, or, in other words, ride real fast.

[ATV DRIVING]

PLASKON: Riders are pushing to open more land, including parks, to these vehicles. One reason is because in some places trails and dunes are getting really crowded.

[ATV DRIVING]

PLASKON: One place they’d like to open is the Mojave National Preserve. So far, most of it is still reserved for foot traffic. It expands across dunes, creosote brush, cinder cones, rocky peaks, squat cedars, and the crooked arms of Joshua trees. The county of San Bernadino and off-roaders have asked for 2,500 miles of ATV roads here, nearly the distance across the United States. Ranger Kirk Gebicke explains why it’s closed to ATVs.

GEBICKE: It’s desert, it’s slow, it’s cactus. You have some of that kind of stuff that may be 50, 75 years old and, you know, it’s trampled by a tire going over it. It’s going to take a long time for that scar, in essence, to heal.

PLASKON: And he says vehicles could also disturb some of the other 400,000 people who visit the park each year.

GEBICKE: Well, number one, just the very nature of wilderness is for a nice, quiet experience. Communing with nature, in essence. And having a vehicle go cruising by on the trail you just hiked three miles to get in kind of ruins it for folks that want that wilderness experience.

PLASKON: Gebicke’s concerns aren’t isolated. Some hunters in Idaho say they don't appreciate the ATVs rolling into their favored hunting grounds that take hours to reach on foot. In Florida’s Big Cypress National Preserve, the National Park Service says ATVs have created 22,000 miles of deep ruts that are disturbing water flow, habitat, and plant growth.

Ranger Gebicke says where there are limits, there’s often vandalism.

GEBICKE: Another common problem is that they will remove the stakes that designate it as a closure, and destroy them or just throw them down on the ground.

PLASKON: Stony Ward, the ATV tour operator, knows that enforcement is difficult. He’s seen off-roaders play cat-and-mouse to escape rangers.

WARD: Well, yeah, I mean, [laughs], I mean, if a guy’s in a Jeep and you’ve got an ATV, you’re going to go to areas where he can’t even fit through, if that’s the type of person you are.

PLASKON: Riders have also been developing political and financial muscle to match their numbers, sometimes with the backing of the oil, gas, and timber industries…also, contractors and anyone else who shares their interest in opening public lands.

The Blue Ribbon Coalition, a nonprofit lobbying group for off-road interests, gets magazine advertising for manufacturers like Yamaha, Honda, and Toyota. The Coalition’s new political action committee donated $50,000 to politicians last year. Its nonprofit side claims more than 600,000 members and spends more than $180,000 a year on legal fees.

Mark Trinka was a Blue Ribbon vice president and lobbyist for trails funding when the Coalition was a lot smaller. He likes the administration’s new federal rules that open the application process for more ATV roads.

TRINKA: Thank God for President Bush. I don’t know what’s going to happen when we get a Democratic regime in Washington. But as long as President Bush has done what he’s done, he’s empowered local government, which is the best kind of government, at the lowest level, to really take control of the land within the boundaries of their counties and their cities.

PLASKON: Under this change, long sought by western governors and counties, a wide variety of people can apply to open roads to ATVs, using a law that predates the internal combustion engine. It’s a tersely-worded 1866 pioneer law intended to encourage settlement of the west. It gave states the right to claim roads on federal land.

The Bureau of Land Management says the new rules probably won’t have much effect at all. However, the National Park Service has said requests for new roads could affect the 68 national parks. There have been road claims in the Sequoia National Forest. Utah is asking for thousands of new roads, and environmental groups say Alaska will ask for many more.

Courtney Cuff of the National Parks Conservation Association says it’s hard to keep track of all the claims and they all probably won’t stick. But some will.

CUFF: There will not be as many places for hikers or passive recreationalists to enjoy if we open up the floodgates for these off-road vehicle users to run rampant across our public lands unabashed.

PLASKON: Off-road enthusiasts say they feel unfairly confined, and it’s time hikers, equestrians, and mountain bikers learned to live with a new addition to the wilderness.

MALE: The whole thing is respecting each other. You know, when you see someone with a horse, you slow way down, shut your engines off and let the horses go by. You see a hiker out there and, you know, you slow by when you’re going past them. It’s just a common courtesy to the other people that are into different activities.

[ATV STARTING]

PLASKON: Wilderness advocates say this shared access with motorists doesn’t work. Even so, federal agencies will consider thousands of requests to open roads and trails across public lands for motorized use.

For Living on Earth, I’m Ky Plaskon from the Mojave Desert.

[ATV DRIVING]

[MUSIC: Brian Hughes “Nasca Lines” A World Instrumental Collection, Putumayo World Music (1996)]

Related links:

- BLM Change in Federal Register/6 January 2003 (PDF file)

- Press Release on Rule from Wilderness Society

CURWOOD: And for this week, that’s Living on Earth. Next week: the average grocery store generates 15 tons of waste each week. And in New Hampshire, one supermarket is using a souped-up compost technology to transform that waste into fertilizer.

MALE: You see these little tiny balls, about an eighth of an inch and sixteenth of an inch in size, that look like little, like dirt, if you will? Just take a whiff of that, if you will, smell that. What do you smell?

CURWOOD: It’s the earthy smell of success at the green grocery, next time on Living on Earth.

And remember that between now and then you can hear us anytime and get the stories behind the news by going to loe.org. That’s loe.org.

[ANIMAL SOUNDS, GALLOPING: Earth Ear “Tuvan Roundup” The Dreams of Gaia, Earth Ear (1999)]

CURWOOD: Before we go, it’s roundup time in Siberia.

[ANIMAL SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: That’s where Ted Levin and Joel Gordon recorded two young Sakha tribesmen who took a break from their herding chores to play a little bit of Jew’s harp and imitate the animals that inhabit the frozen steps.

[ANIMAL SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by The World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at www.loe.org. Our staff includes Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Maggie Villiger, Cynthia Graber and Jennifer Chu, along with Al Avery, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson, Jessica Penney and Liz Lempert.

Special thanks to Ernie Silver and New Hampshire Public Radio. We had help this week from Katherine Lemcke, Jenny Cutraro and Nathan Marcy. Allison Dean composed our themes. Environmental Sound Art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our technical director is Chris Engles. Ingrid Lobet heads our western bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor. And Chris Ballman is the senior producer of Living on Earth.

I’m Steve Curwood, executive producer. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation. Major contributors include: The National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science; and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living on Earth's expanded internet service.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth