April 18, 2003

Air Date: April 18, 2003

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Black & White – & Green

View the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood talks with three environmental journalists about how their beat has developed and where it’s going. Los Angeles Times editor Frank Clifford, Newsday reporter and president of the Society of Environmental Journalists Dan Fagin, and director of the Michigan State University Environmental Journalism program Jim Detjen all participate. (11:00)

Environmental Health Note/Grocery Gap

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on supermarket shuttle services that benefit both the customer and the store. (01:20)

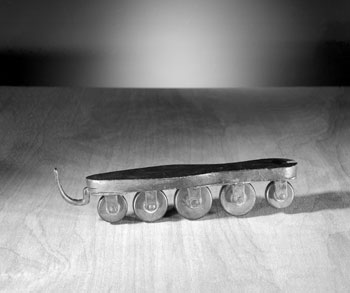

Almanac/Holy Rollers

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about the volito. This early roller-skate was patented 180 years ago, with inline wheels that set a new standard for maneuverability. (01:30)

City Life

View the page for this story

For the past two years, Living on Earth has been teaching radio production to students at nearly a dozen, mostly inner-city schools across the country. Not surprisingly, the students have an instant understanding of the most immediate urban environmental issues –safe, livable neighborhoods, a sense of community and of course, the dream of a faster school bus. For Earth Day, we share some of their stories with you. (10:45)

Hedgehog Roundup

View the page for this story

The Scottish Natural Heritage recently began a cull to decrease the population of hedgehogs on the western islands of Scotland. The prickly mammals threaten the native bird populations there by feeding on the eggs. Host Steve Curwood talks with Kay Bullen, a volunteer with a hedgehog rescue group, who’s trying to thwart the cull by relocating the creatures. (03:00)

Emerging Science Note/Sex & the Single Worm

/ Maggie VilligerView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Maggie Villiger reports on the way radioactive pollution is changing the sex lives of worms near Chernobyl. (01:30)

Coalminer’s Daughter Turned Activist Wins Top Enviro Prize

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

This year, the North American winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize is Judy Bonds. Bonds is a coal miner’s daughter who became a full-time activist against mountaintop removal mining after she saw her beloved West Virginia mountains and streams being destroyed. West Virginia Public Broadcasting’s Jeff Young has this profile. (07:00)

Coal Water Fish

/ Erika CelesteView the page for this story

In the last decade, it was discovered that many of the abandoned coal mines in southern West Virginia held a surprisingly high quality resource: water. Now, the state is using these underground springs to spawn a new industry—raising fish. Erika Celeste of West Virginia Public Broadcasting reports. (05:00)

Not-So-Wholesome Maple Syrup

/ Lois SheaView the page for this story

It’s spring, which means the sap is rising and the maple sugar is flowing. Writer Lois Shea went sugaring recently, and talks about this New England ritual. (03:30)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodGUESTS: Frank Clifford, Jim Detjen, Dan Fagin, Kay BullenREPORTERS: Jeff Young, Erika CelesteCOMMENTARY: Lois SheaNOTES: Diane Toomey, Maggie Villiger

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood with this Earth Day edition. Coal mining has drastically altered the landscape of West Virginia. But one woman didn’t realize the extent of the devastation until she viewed it through the eyes of a child.

BONDS: And then I heard my grandson say, "Mawmaw, what's wrong with these fish?" And I looked around him, and there was dead fish laying all over the stream. And that was the slap in the face.

CURWOOD: Judy Bonds decided to fight back, in the process building unlikely coalitions and winning the Goldman Environmental Prize. Also, voices from young America.

CINTRON: There are times when I'm sitting on my steps, and I see rats from the abandoned house running across the street. If more people spoke out, maybe something could get done. But sometimes I feel like I'm the only one who cares.

CURWOOD: We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth, coming up right after this.

[NPR newscast]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and HeritageAfrica.com.

Black & White – & Green

CURWOOD: Welcome to this Earth Day edition of Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Some 13 Earth Days ago, I created Living on Earth with one basic concept, that no matter what else was going on in the news, this program would devote its time to telling you about environmental change. And as this program has evolved, so has environmental journalism.

Here to talk about the trends in this field are three practitioners. Frank Clifford is an editor at the Los Angeles Times and Dan Fagin is a reporter for Newsday and president of the Society of Environmental Journalists. And I want to start with Jim Detjen, director of the Environmental Journalism Program at Michigan State University, and ask you, Jim, to take us back to the early days of environmental reporting. How do you describe that era to your students?

DETJEN: Well, with my students, we go back well into the 19th century. So, we will look at some of the early campaigns by magazines to cut down on the amount of over-hunting of birds and other species. We also look at some of the efforts by early writers such as John Muir to create national parks. And I think you could argue that there have been people writing about conservation and environmental issues almost as long as there has been civilization.

CURWOOD: So, when does that change? This sounds like this is all advocacy work. When does that become journalism, in your eyes?

DETJEN: Certainly, maybe, the last century. Really with the rise of the Associated Press and some of the ideas of objective journalism, it became less advocacy, probably more traditional, more standard journalism that we're familiar with today.

CURWOOD: Jim Detjen, how soon do we see newspapers and radio and television assigning an environmental reporter on the environment beat?

DETJEN: Maybe since about the 1960s, there were designated environmental beats. It was still pretty much a fringe area. And then, it really blossomed in the 1970s. And I would argue it's fairly steadily grown since then, although it has been episodic, and there are cycles.

CURWOOD: Now, the environmental beat continues to evolve in your newsroom at the Los Angeles Times, Frank Clifford. How many reporters do you have covering the environment?

CLIFFORD: Probably eight all together. Six based in Los Angeles, one in Orange County, one in the paper’s Washington bureau. There are other people, regional and national reporters, who write about the subject fairly frequently as well. Maybe the best way to do this is to talk about how the division works at the moment, which is somebody covering coastal issues, air quality, forests and fresh water, human health issues as they relate to the environment, parks, wildlife and public land, and urban environmental issues. And I may have missed an assignment there, but that gives you an idea of the breakdown right now.

CURWOOD: I want to bring Dan Fagin in here. Dan, you work at Newsday. How many environmental reporters do you have at your shop?

FAGIN: Well, Steve, we have two people covering the environment fulltime. And we have a person in Washington who spends about half his time writing about environmental issues.

CURWOOD: Jim Detjen, how common is the two-and-a-half configuration versus the eight-reporter configuration.

DETJEN: The Portland Oregonian has quite a number. The L.A. Times, I think, is one of the leaders. I think, more typically, it's one or one-and-a-half or two. But there might be one designated environmental writer, and then there are people who regularly write about environmental issues from other beats as well.

CURWOOD: Dan Fagin, let's turn to you now in your role as President of the Society of Environmental Journalists, and have you look at the national scene for us. How do the types of changes that Frank describes at the L.A. Times fit in with trends around the country? Where is coverage getting beefed up? Where is it getting cut?

FAGIN: Well, it's hard to say that it's getting cut, in particular, in any place. I mean, I think the general trend is a positive one. Certainly, as a result of the war and what's happening with terrorism, people who cover the environment, many of them have found themselves being pulled off to do other things. But I'd consider that sort of a temporary thing. In the long run, the trend line is pretty positive.

Environmental reporters are getting more knowledgeable. They're getting more specialized. Editors are recognizing that it's very important that environmental writers really have a grounding in the basics of the science and the policy. And so, the kind of specialization that Frank talks about at the L.A. Times is happening in other places, although rarely to the extent of eight designated environmental reporters.

CURWOOD: What most encourages you about coverage of the environment these days?

FAGIN: I think the most positive sign that I see is there's really an understanding now that these issues are not black and white, that they're complex. It's not just a question of getting the obvious one side and the other, but that sometimes there are many sides. And the importance of integrating data and empirical science into coverage. I see this improving a lot.

CURWOOD: Frank?

CLIFFORD: Well, let me change the emphasis a little bit. I think that a lot of the people who cover the environment these days are somewhat frustrated because they don't think that they’ve been able to sort of generate the discussion and the debate that ought to occur around policy shift quite as dramatic as what we've been seeing since the Bush administration took over. And I think a lot of journalists are asking themselves, is it because we are too bland, too objective? Is it time for the kind of rebirth of a kind of advocacy journalism that characterized the early days that Jim was talking about? I think that’s an interesting discussion. I think, maybe, that the push for professionalism can be confused with a kind of timidity.

CURWOOD: Dan, where do you weigh in on this?

FAGIN: There's often a feeling among some environmental reporters that the way to be professional, the way to be a "real journalist,” is to be very clinical and bloodless in your writing. And to always, you know, be scrupulously 50 percent from one side and 50 percent from the other. And to sort of suck the life out of your stories, and to not pay attention to things like narrative and writing and real people impact. And so, you know, the folks who say that, well, what we need is more advocacy in our journalism, I think, are missing the point. What we really need is terrific, highly competent, but also high-impact journalism, journalism that actually resonates with readers and viewers.

CURWOOD: Now, Jim Detjen, you spent a fair amount of time with environmental journalists abroad. They, as a whole, I think, are far more advocacy-oriented that the folks that you find in the United States. How bland do you think the coverage is here in this country?

DETJEN: I think there could be a lot more aggressive reporting. I think, particularly since September 11th, I think there has been a lot of efforts to scale back some of environmental regulations, environmental laws, access to information, and a lot of that has not been reported particularly well because it's been drowned out by the coverage of the war on terrorism and the war itself.

CURWOOD: What other areas of environmental journalism do you see as perhaps not doing as well as they might?

CLIFFORD: I would like to see more science pages, more science sections in newspapers. We're beginning to see health sections in more newspapers. I think that what sometimes is missed in our efforts to stay abreast of policy and political debate about various environmental issues is just purely the wonder of discovery. And I think it would be nice if we could sort of create space for that kind of writing as well.

CURWOOD: Jim Detjen?

DETJEN: I'm concerned about the drop in coverage on television. One study that’s done by the Tindall Report which monitors the amount of air time there is on network newscasts, found that, in 2002, there was about only half the coverage of what there had been in 2001. And you can understand that this is episodic, and we've had a war on terrorism. And now, a war against Iraq.

But television coverage is very inconsistent. You can have high water periods of the late 1980's, when you had a big story like the Exxon Valdez, and there was a great deal of coverage. And then it can plummet as it goes on to something else. Not many television stations have designated environmental reporters. So, you could have a lot of coverage and then very little.

CURWOOD: Jim, what's the message that the public gets when they don't see environmental stories on the tube, or they're buried in the back of the paper?

DETJEN: The message is that these issues are not as important as they once were. And therefore, the public looks at other issues.

FAGIN: It's really quite remarkable that the TV coverage that Jim mentioned, which we can all see and probably understand the reasons, considering everything else that was happening in the world. But it is quite remarkable that it's happened at a time when, you know, we've seen really more at least potential news on environmental issues coming out of Washington than in many, many years. And while there have been stories, it does seem that, because the print stories aren't really picked up on the network news, that those stories don't really seem to resonate as they would have in the past.

And that’s really a frustration because, as Jim pointed out, this is a time when the coverage could really serve a very important public purpose. And that is to clue everybody in about what's going on so we can have a healthy debate on what should happen and why.

CURWOOD: How well informed do you think the public is now about environmental issues, particularly lately as environmental stories haven't been getting the play that they had even a year ago?

CLIFFORD: I would guess that the public, in general, isn't aware of the developments that I think Dan was talking about a minute ago, simply because they're not being reported on television. And not that many people are reading those newspapers that do write about these issues a lot. I don't want to presume to say what people know, and how aware they are of things. But I know that, if I were to base my knowledge of current affairs in the environment on watching television, I don't think I'd know much.

CURWOOD: What about you, Jim Detjen? I mean, you're sending all these students out into the world to do environmental journalism. Where do you see the prospects for the beat over the next ten years?

DETJEN: We've discussed some of the inadequacies and maybe some of the problems with environmental reporting. But I really think the general curve has been upward. The number of members of the Society of Environmental Journalists is really at record heights. The number of programs in environmental reporting at education and in universities are very high. We had more Pulitzer Prizes won for environmental journalism in the 1990s than in all of the 1960s, '70s, and '80s combined. So the general trend is upward. And I see that as quite positive.

CURWOOD: Frank Clifford is an editor at the Los Angeles Times and author of “The Backbone of the World: A Portrait of a Vanishing Way of Life Along the Continental Divide.” Dan Fagin is President of the Society of Environmental Journalists and a reporter for Newsday in New York. And Jim Detjen currently directs the Environmental Journalism Program at Michigan State University. Thanks to you all for joining this conversation.

FAGIN: Thank you, Steve.

DETJEN: Thank you, Steve.

CLIFFORD: Thank you.

Environmental Health Note/Grocery Gap

CURWOOD: Coming up, this place called home as seen by young people in urban America. First, this environmental health note form Diane Toomey.

[MUSIC: Health Note Theme]

TOOMEY: For people who live in urban low-income neighborhoods, fresh, healthy food can be hard to come by. For one, full-service supermarkets are scarce in these areas. What's more, many of these residents can't shop elsewhere because they don't own cars. The so-called grocery gap means these people must buy their food at small convenience stores that usually offer a small selection of nutritional food at higher prices. This may, in part, explain why low-income households eat so few fruits and vegetables.

According to one study, only about a quarter of people who earn less than $15,000 a year eats the recommended five or more daily servings of these foods. Now, a study done by researchers at the University of California at Davis has found that a supermarket shuttle service may not only benefit customers, it may be good for business, too. Researchers looked at the feasibility of shuttle programs in a number of low-income California neighborhoods, and found that the handful of supermarkets that offered a free shuttle generated two to three times the revenue from produce and perishable items compared to the industry standard.

One Los Angeles store estimates that its shuttle service, which offers rides home to customers who spend at least $25, generated more than $27,000 in additional weekly revenue. What's more, a shuttle service appeared to cut down on the theft of shopping carts that are often taken by people who don't have cars to cart home their bags of groceries. That’s this week's health note. I'm Diane Toomey.

CURWOOD: And you're listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Govinda “City of Pleasures” Erotic Rhythms from Earth – Earthtone (2001)]

Almanac/Holy Rollers

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: UNKNOWN “The Roller Rink Song”]

CURWOOD: An apparatus to be attached to boots, shoes, and other coverings for the feet for the purpose of traveling or for pleasure. That's the official description of Robert John Tyers' volito roller skates, patented in London 180 years ago this week. Mr. Tyers avidly ice-skated and his volito, from the Latin verb meaning "to fly to and fro" allowed the Englishman to enjoy gliding year-round.

Now, there were earlier versions of roller skates, but they couldn't manage curves with the aplomb of the volito. An earlier London inventor named John Joseph Merlin rolled out his wheels at an elegant London party in 1770, turning heads as he skated into the room playing a violin. Unfortunately, recalled a newspaper account, “not having provided the means of retarding his velocity or commanding his direction, he impelled himself against a mirror, dashed it to atoms, broke his instrument to pieces, and wounded himself severely.”

The Volito Skate

(Photo: National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

Years later, John Tyers designed his roller skate with five wheels. A larger wheel in the middle allowed skaters to use their weight in combination with the smaller wheels to skate in curves. It was only a matter of time before roller derby and roller disco hit the scene. Then, in 1980, two hockey-playing brothers remodeled an old pair of skates and came up with the latest incarnation of Mr. Tyers' volito: the Rollerblade.

And for this week, that's the Living on Earth almanac.

[MUSIC]

City Life

CURWOOD: For more than two years, Living on Earth has been bringing the skills of environmental radio journalism to students in nearly a dozen schools across the nation. We call it the Ecological Literacy Project, and most of our schools are in urban areas. For Earth Day, we share some of their stories with you.

CINTRON: I live in the part of Camden known as South Camden. Across the street from my home is an abandoned house, one of dozens in my part of town.

CURWOOD: Rebecca Cintron is a senior at Camden High School in Camden, New Jersey.

CINTRON: It has been unoccupied for the past eight years. About four years ago the house caught on fire, but the fire wasn't merciful enough to burn the house down. The flames left the house charred, doors gone, and a huge hole in the roof. And there it still stands, making the rest of the houses on my block look dirty. Now that house is a health hazard, jeopardizing the safety of the people in the neighborhood.

There are times when I am sitting on my steps and I see rats from the abandoned house running across the street. The yard next to the house is full of trash and weeds. The filth is attracting all kinds of bugs, like ticks and roaches. These bugs wander and become a menace to the surrounding houses.

When I was younger, the house was a drug house. There were always a lot of people walking in and out. One day the police raided the house and everyone inside the house got arrested, including the owner. And after the house caught fire, nobody could live there. Unfortunately, this is not the only abandoned house in Camden. There are hundreds of abandoned houses in my city. Sometimes people leave because they can't afford it anymore. Like the house on my block, the owner gets arrested and the city never does anything about the property.

Whatever the reason, the city of Camden needs to do something about the house. Officials could just knock down the house and build another in its place. If not, the city should demolish it and just leave it as an empty lot: cleaned and safe. Or they should put the property up for sale. Maybe someone will want to buy it and fix it up. But a solution has to be found fast. The city needs to take action before something bad happens. The house could catch fire again and someone could get hurt this time. Or some of the neighborhood kids could be playing inside and pieces of the house could fall on them.

I personally think that there are so many abandoned houses in Camden because the city is lazy. If more people spoke out, maybe something could get done. But sometimes I feel like I'm the only one who cares.

CURWOOD: That was Camden High School senior Rebecca Cintron. Up in Harlem, one landlord is trying to do something about the environment by sprucing up his apartment building. But eighth-grader Tasha Eaddy is angry that she and her friends are being swept off the front stoop in the process.

[JUMPING ROPE]

FEMALE 1: Why you gotta jump like that?

FEMALE 2: I told you I jumped ...(inaudible).

EADDY: I used to hang out in front of my building with my friends. We watched people walk past and look how they dressed, and gossip and flirt, and play double dutch and laugh. One night my mother came back from a tenants meeting and told us it was going to be some new rules. The landlord said that we can't hang out in front of the building, no more loitering in the hallways. If you get written up three times, you're going to have to find another place to live.

The landlord thinks that we shouldn't stay in front of the building. It's because he thinks we sell drugs and drink, that sometimes leads to fighting. Me and my friends don't do that stuff. We don't cause any trouble. The landlord wants us to stay in the back yard, but the sand is dirty and people used to get ringworms from it and that's disgusting. The bench is broken and we don't have no swings anymore. The landlord is fixing it up. The only thing he has fixed already is the basketball court.

We could walk to the park but our mothers don't want us to walk there alone. The landlord is fixing up a bunch of stuff, putting in a new fence, putting in new swings and seesaws. If we get people who are causing problems to move out, he will get new people to move in. He wants the new people to feel welcome and safe and feels that nothing is going to happen.

People who don't deserve it are really getting written up. My family already have two letters and they’re not my fault. My brother's friends shook a wet umbrella on the security guard and got him wet, and the guard blamed it on my brother. I don't know how the guard could mistaken my brother, because they really don't look alike except they have really dark skin. Then, a week later, my mom's friend came to visit. He left and went downstairs and waited for someone. The guard told the landlord he was loitering, so my family got another letter. If we get one more, that means we have to find a new place to live.

It's not fair. I'm tired of staying in the house every Saturday and Sunday. I like to watch TV, but sometimes I like to go outside and get some air. Me and my friends just want to hang out, that's all.

[GIRLS TALKING & PLAYING]

CURWOOD: Tasha Eaddy is an 8th grader at Harbor Arts and Science Charter School in New York City. When asked to write about somewhere that gave him a sense of place, senior Byron Huitz chose to write about the sometimes dangerous, sometimes liberating train tracks that run near his home in the Hyde Park section of Los Angeles.

HUITZ: Walking on top of red and grey rocks, knocking them over, looking on the wall for graffiti painted in black and silver, balancing myself on one rail that's connected to old brown wood, I remember when I was four years old, walking along these railroad tracks, walking alone on my way to kindergarten, stepping over the wood cracking when I’m on top, taking a look over my shoulders, seeing a big yellow light coming slowly towards me.

It was here when I was in first grade the first time I seen a girl get jumped. I was with my friend coming from school. I saw two groups of girls that were arguing. One group was wearing black football jackets. The rest of them wore white t-shirts. As we got closer, the conflict started to ignite more and more, like a cigar. One of the girls that had a football jacket picked up a bright-colored brick and tossed it in another girl's head, knocking her down on the ground. Blood began to drip out of her head and down her cheek. I saw her white shirt turn red. My friend stayed to watch but I was disturbed and left by myself.

As I got older, I started to like the tracks. When I was 12 years old I used to ride by on my bicycle, slowly so I could see the new graffiti on the wall. I was curious to see the new characters or anybody crossing out another crew.

A few times I rode the trains, even though they were just meant for cargo. Sometimes I ride to my friend's house. I waited for the train to pass by and then I would chase it, throwing my backpack on first. The most exciting part was that adrenaline rush getting into the cargo, because that was a ticket if police caught you.

Then last year, the line got shut down and the trains stopped coming. Right now, as I go through the railroad tracks, I don't hear any more whistles blowing by. Less graffiti on the walls, less crime. No more traffic waiting for the train to pass by.

CURWOOD: That was Byron Huitz, a senior at Crenshaw High School in Los Angeles. Stealing rides on a freight train is one way to get around, but for many people living in the city, buses are the only way to get where they're going. Chicago high school 9th grader Tiana Clemens spends an hour a day riding the bus home from school, but sometimes, she says, it feels like an eternity.

CLEMENS: I wonder how long is it going to be for me to get to my destination. The bus is late yet again, picking us up from Queen of Peace High School. As I sit on the bus, I look out the window and see how much of a beautiful day it is. Beauty, but so cold.

We sit here and wait on the bus for quite some time, and then we finally pull off.

[BUS DRIVING]

I sit here continuing to look out the window as the bus jerks back and forth, stopping and going. In the car, this happens but believe me, it's much more of a comfortable and peaceful ride. But with a car, all you have to worry about is the bobbing and weaving in and out of traffic. You don't have to worry about stopping and picking up people and sitting next to the most disgusting person you've ever seen.

We make a stop, and I look out the window. And as I look, I see litter upon litter upon litter on someone's grass. I ask myself, how can someone throw it down there? And how can someone else just leave it? But then I think about all the times I've done it myself.

The bus moves so slowly and traffic will be so much easier if the buses and trucks had their own lane, because then you wouldn’t have to worry about being caught being a slow bus or a slow truck. [laughs] I sit here and imagine the bus flying over cars, getting me to my destination quicker.

The bus stops at my stop.

[BUS SOUNDS]

As I get off the bus, I look back at the bus and I wonder, how long will it take for someone else to get to their destination with the jerks back and forth, back and forth? Will you ever get to your destination on time?

CURWOOD: Tiana Clemens is a ninth-grader at Queen of Peace High School in Chicago. She produced her commentary for Living on Earth's Ecological Literacy Project.

[BUS SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: To hear more stories by students, please check our website at loe.org. We had help from a number of teachers and mentors this week in helping to put together the student commentaries. Special thanks to Cynthia Thomashow at Antioch New England; Mhari Saito, Gwen Shaffer, and Lynn Johnson in Camden; Miyuki Jokiranta and Jen Watt in New York; Tammy Bird Beasley and Dennis Foley in Los Angeles; and Jesse Hardman and Anna Kraftson-Hogue in Chicago.

[MUSIC: West African Balafon Ensemble “Farfina” The Pulse of Life – Ellipsis (1992)]

CURWOOD: Elephants never forget. That's what I said when my safari guide in the African savanna asked me what I knew about elephants. That's right, he said, but there's something more. Elephants also regard this place as their own, and we are merely tolerated as intruders as long as we follow the rules. We couldn't get too close in our Land Rover, we shouldn't make rude gestures or sounds, and we needed to keep an eye on those big ears. If those ears started flapping, it meant we were being challenged and we needed to back down. Oh yeah, one other thing the guide said: we'll always keep the Land Rover headed in a direction where we can hit the gas and be gone. On a bumpy track, he warned, the elephants could almost outrun a truck.

It didn't take us long cruising across the savanna to find a herd of elephants. They stopped and we stopped, and a baby waddled under his mother, tucked his trunk to one side, and began to nurse. Mother elephant gave us a glaring eye from atop her magnificent face, and we stayed still. And then I thought she even smiled a bit with pride as we quietly drove away.

Sometime later I met a colleague who was just back from Pilandsberg National Park and he was breathless. "You wouldn't believe the elephants!" he exclaimed. “A couple of them were lined up together, their ears flapping, when suddenly they started to charge. My guide jammed the truck into reverse, spun it around and stood on the gas just moments before I think they would have got us.”

Living on Earth wants to give you a chance to get up close to elephants in the wild on your own African safari, as long as you remember to watch those ears. Thanks to Heritage Africa, we're giving away a 15-day trip for two on the ultimate African safari, with visits to several of Africa's most spectacular game preserves, such as Kruger, where I saw these elephants, and the Serengeti.

For more details about how to win this 15-day African safari, just go to our website, loe.org. That's loe.org, for the trip of a lifetime.

[MUSIC]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include the Oak Foundation, supporting coverage of marine issues, and the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation. Support also comes from NPR member stations and the Noyce Foundation, dedicated to improving math and science instruction from kindergarten through grade 12, and Bob Williams and Meg Caldwell, honoring NPR's coverage of environmental and natural resource issues, and in support of the NPR President's Council.

Related link:

Living on Earth - Ecological Literacy Project

Hedgehog Roundup

CURWOOD: In 1974, four hedgehogs were sent to the Hebrides Islands off the western coast of Scotland to weed out insects and slugs in a local garden. But since then, the prickly mammals have multiplied to 5000 and now threaten the native bird populations there by feasting on their eggs. So the Scottish Natural Heritage, a government-appointed agency, has been culling the hedgehogs by lethal injection on the island of North Uist.

Several animal advocacy groups are trying to thwart the cull by relocating the hedgehogs to the mainland. Kay Bullen, a volunteer with the Uist Hedgehog Rescue Group, has been searching for hedgehogs under the cover of darkness for the past two weeks. Hello there.

BULLEN: Hello.

CURWOOD: For those of us who don't normally see hedgehogs ambling about, what do these guys look like?

BULLEN: Well, they're just very inoffensive little animals. They're smaller than a cat and they've got lots of prickles. And if you do look at the faces, they've got very cute little faces as well. And we consider them a gardener's friend over here, because they eat lots of things like slugs and snails and creepy crawlers that are eating people's plants.

CURWOOD: Now, why wait for nightfall to go looking for these creatures?

BULLEN: Because at night, that's when there's lots of slugs and snails and things like that around, so therefore hedgehogs are nocturnal.

CURWOOD: Have any of them been particularly evasive?

BULLEN: Yes, unfortunately. We've got one that we've been trying to catch for about five or six evenings, and every time we visit the area where we know he is, he disappears down, or she disappears down a rabbit burrow. And I can tell you it's a she because last night we did go out and we did actually manage to catch her, and she's a little girl, and she weighs 420 grams.

CURWOOD: What's her name?

BULLEN: We were calling her the Scarlet Pimpernel.

CURWOOD: [laughs] Now, when you catch these guys, what noise do they make?

BULLEN: They can huff and they can hiss. They try and intimidate by sounding really sort of fierce. And they raise their prickles when they're frightened. And a big hedgehog can have about 7000 prickles.

CURWOOD: How fast are they?

BULLEN: Well, they can run about 5 or 6 miles an hour.

CURWOOD: How many have you rescued so far?

BULLEN: We've rescued around 54 so far.

CURWOOD: Where are you going to relocate these hedgehogs?

BULLEN: Well first of all, they travel over to a place called Glasgow, and then they're going to be cascaded down throughout the rest of the country. But we don't just release them anywhere. There's badgers, the predators of hedgehogs, so we want to make sure there's no badgers in the area. And, I mean, people's gardens are ideal spots to release the hedgehogs.

CURWOOD: Now what happens if one of your team encounters someone from the Scottish Natural Heritage? What happens then?

BULLEN: We tend to avoid each other by mutual consent. We just want to get on and find as many hedgehogs as we can ahead of them. So, I mean, really, it is a race against time. We do want to go up there, and we want to catch as many as possible.

CURWOOD: Kay Bullen is a volunteer with the Uist Hedgehog Rescue Group on the Hebrides Islands. Kay, thanks for taking this time with me today.

BULLEN: You're very welcome.

Related link:

British Hedgehog Preservation Society

Emerging Science Note/Sex & the Single Worm

CURWOOD: Coming up, fighting mountaintop removal in West Virginia. First this note on emerging science from Maggie Villiger.

[MUSIC: Science Note Theme]

VILLIGER: New research shows that chronic low-level radioactivity in the environment can induce worms to change their sexual behavior. Some Ukrainian worms are opting to have sex with each other rather than stick with their normal asexual reproduction. Scientists compared these aquatic worms living in two similar lakes. The only difference was one lake had concentrations of radioactive strontium 90 that were more than 50 times higher than normal, thanks to the nearby Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. Worms living in that contaminated lake had higher numbers of mutated cells in their bodies. And the more chromosome damage a particular worm had, the higher the chance it was looking for a mate.

Researchers think the worms' unusual sexual reproduction may be a survival strategy, since the offspring receive genes from two parents instead of one. Natural selection would promote genes that increased chances of survival in the new radioactive conditions. This study is one of the first to look at how wildlife is affected by radioactive pollution. The researchers hope to examine the phenomenon in other species around the world.

That's this week's note on emerging science. I'm Maggie Villiger.

CURWOOD: And you're listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC Ali Akbar Khan “India Blue” A World Instrumental Collection – Putumayo (1996)]

Coalminer’s Daughter Turned Activist Wins Top Enviro Prize

CURWOOD: The Goldman Prize is often called the Nobel for the environment. Each year, activists on each continent receive the award worth $125,000 for their work. The winner this year for North America is Judy Bonds, the West Virginia woman working to stop the coal mining method called mountaintop removal. Jeff Young of West Virginia Public Broadcasting has this profile of a coal miner's daughter fighting to end a coal mining practice.

YOUNG: A former post office in Whitesville, West Virginia is home to the grassroots group, Coal River Mountain Watch. It might as well be home for the group's director, Judy Bonds. Most of her waking hours are spent here organizing protests, lobbying lawmakers, and writing to editors and senators to stop mountaintop removal. The 51-year-old Bonds points to a wall-sized map of Southern West Virginia. It shows the contours of the state's coal country.

BONDS: I can tell you exactly where they're heading by looking at a topomap, a USGS map. These coal companies want the cheap, easy, quick, fast way, regardless of human concern. And what we're looking at is the prize, called Pond Knob.

YOUNG: Bonds thinks Pond Knob on Coal River Mountain could be the next ridge flattened by mountaintop removal. The mining blasts the tops from hills to expose coal. Tons of leftover rock and dirt are dumped into valleys, burying hundreds of miles of Appalachia's headwater streams. The mining has so altered the landscape that the map Bonds pours over is no longer accurate, but she still scans for tiny signs of hope, like the crosses marking small family cemeteries.

BONDS: There's a law in West Virginia, and they cannot mine within 300 feet of a cemetery. They have to give some sort of protection to that cemetery. Basically, I would say our dead ancestors are helping us to fight these coal companies, and are another way to put a chair against the door to keep the wolf out. We're backed in the corner. We're using any means we can to save our lives.

YOUNG: Bonds knows the mining is changing more than the land. It's changing the people who live on it. It's certainly changed her.

Judy Bonds delivering a speech in Washington, D.C. 2002

calling for the end to mountaintop removal.

(Photo: Deana Steiner Smith)

[SOUND OF CAR STARTING]

YOUNG: Just six years ago, Bonds was waiting tables at Pizza Hut. She lived quietly in one of the sharp, narrow valleys people here call "hollows." Marfork Hollow was her family's home for six generations. Now, Marfork is the name of a coal company, and Bonds is just another visitor driving by.

BONDS: Every time I pass by this hollow, I look, and it hurts. It breaks my heart, because this is where I was born and raised.

YOUNG: Bonds remembers when Massey Energy Company's Marfork mine opened ten years ago. It brought truck traffic, dust, and the noise of blasting. The extent of the damage became clear the day the stream near her house turned black with coal waste.

BONDS: And I heard my grandson say "Mawmaw." And I looked at him and he said, "What's wrong with these fish?" And he had both his little hands full of fish, dead fish. And I looked around him and there were dead fish laying all over the stream. And that was a slap in the face.

YOUNG: Bonds eventually sold her family land and moved about 10 miles south. She watched as more acres were mined and more coal wastes blackened streams. She didn't know what she could do about it until she attended a rally against mountaintop removal and realized she was not alone.

[FOLK MUSIC PLAYING]

YOUNG: Former West Virginia congressman turned activist, Ken Hechler, performed that day six years ago. Bonds joined the group Coal River Mountain Watch, and Hechler watched her go quickly from a bystander to a leader.

HECHLER: There are several things about Judy that developed as her activism developed. First of all, she's a person of great determination and great courage and great dedication. And secondly, she's a person who inspires confidence among people that she helps to organize.

YOUNG: In 1999, Hechler and Bonds organized a march to commemorate the Battle of Blair Mountain, an historic moment in the early effort to unionize the state's coal miners. Hechler says he knew Bonds had grit when the small group of marchers was surrounded by angry counter-demonstrators.

Judy Bonds (center) at a protest against mountaintop removal

at the West Virginia State Capitol in 2002.

(Photo: Vivian Stockman, OVEC)

HECHLER: We were attacked by a group of toughs. And I looked over and I saw Judy Bonds, and she had a look of great determination on her face. I started out being scared, and then terrified, but I got inspired by her courage.

YOUNG: Many of those counter-demonstrators were coal miners. Bonds realized she needed to reach out to miners who saw her work as a threat to theirs. The United Mine Workers of America fights many of the things conservationists want, including restrictions on mountaintop removal. But union representative Mike Caputo says he was able to work with Bonds' group on some issues.

CAPUTO: The bridge was built by Judy when we sat down and chatted with her, and spoke quite frankly that there's going to be issues that were probably going to be at odds on them, maybe might even be fighting each other at one time or another. But we've seen some common ground there, and we've seen that there are many, many issues that we can join hands on. And Judy helped develop that relationship.

YOUNG: Bonds and Caputo fought for better regulation of overweight coal trucks, and the union helped her point out the poor environmental record at many non-union mines. Bonds is proud of the headway she's made with the union and with state regulators. But it's hard to point to solid victories. Coalfield residents twice won major court cases limiting mountaintop removal, only to have both rulings overturned. And the Bush administration is changing federal rules to allow mines to dump rock and dirt in streams.

But if Bonds grows discouraged, she returns to the stream at Marfork Hollow to remind herself what she's working for.

BONDS: The celebration of life was everyday, the connection everyday to the community and to the land, and to the rivers and the streams. And that's basically what we're trying to preserve. This is innocence. That's what we're trying to preserve, the innocence, the innocence of a time left behind, of a connection to community, and to people, and to heritage, and culture, and to the environment. It's a tradition that goes on.

[SOUNDS OF TRUCKS]

YOUNG: A rumbling truck brings her back to the present, and a coal company security guard approaches.

SECURITY GUARD: Can I help you?

BONDS: I was just here looking at where I used to live at. I just come up to look. I haven't been here for a while.

SECURITY GUARD: The only thing we ask now is you get hazard trained, because this is coal company property...

YOUNG: Bonds asks the guard if he heard spring peepers sing this year, or the hoot owl that roosted in the walnut tree her father planted. Soon the two are talking about wildflowers and black bears. Judy Bonds is back to work in her own subtle way, building bridges wherever she can.

For Living On Earth, I'm Jeff Young, in Marfork Hollow, West Virginia.

Related link:

The 2003 Goldman Environmental Prize

Coal Water Fish

CURWOOD: Mountaintop removal may be the latest method to get to coal, but over the years the more traditional way has been to dig underground. And in West Virginia there are thousands of underground mines that have been abandoned. Some of those mines opened up springs, and are now being tapped as freshwater supplies for fish farms. Erika Celeste of West Virginia Public Broadcasting reports.

CELESTE: Hidden deep in the hills of West Virginia, down a winding mountain road, along a forgotten dusty trail, next to an abandoned coal mine, is a most unexpected site. There in the middle of nowhere looms a giant glass structure, like something from outer space. This is Lillybrook Trout Farm.

Even more unusual than the farm itself is the source of its water. Project manager Matt Monroe says Lillybrook trout are raised in water bubbling up from an aquifer in the old coal mine.

MONROE: I think people get the image of the fish running through the coal mines, but it's actually, gravity flows out of the ground. Actually, we run it through some aeration and some nitrogen stripping towers, and then we run it down into our building through our fiberglass tank system.

CELESTE: A short walk around the hatchery leads to the mouth of the mine, and the elaborate system that gathers, purifies, and aerates the water. The water is then piped inside to a series of large, round tanks, ranging in size from 10,000 gallons to 28,000 gallons. That's where the fish are raised. The mine behind Lillybrook closed in the 1950s, after the coal ran out. Steve Miller, director of operations for the state's Department of Agriculture, says it would take another 40 years to realize the mine held another valuable resource.

MILLER: This water kept boiling out of the mines. And they're always looking for some way to use that land that's not used anymore. Their research showed that the water was clean enough and cold enough to sustain a trout operation. That gave them a good opportunity.

CELESTE: Most mines have a high sulfur content, which produces high sulfur water, which is toxic to fish. But southern West Virginia's coal mines are unique because they have low sulfur content. Project manager Matt Monroe says that, and the water temperature, make it a high quality resource.

MONROE: The temperature of it is one of the, probably, top points. Some of the other places that raise rainbow trout in the other states use a lot of surface water, which, basically, in the summer months, really warms up and it's real hard on the trout. There's low oxygen levels. The thing about this water being underground, it's basically the same temperature all year around, 55 degrees Fahrenheit.

CELESTE: Water from the southern coal mines has been so ideal for raising fish that now 17 farms in West Virginia use the source. Most are raising rainbow trout, but a few are experimenting with other types of fish. One farm, for example, is experimenting with Arctic Char, which is often used for sushi. Monroe says he's pleased with the results.

MONROE: We're making very good use of post-mining land. We're using the water in an efficient way to raise farm-raised fish that are high quality. And they're very fresh because we bring them straight from our farms, right to the processing plant.

CELESTE: Once processed, Lillybrook fish is sold to grocery stores, restaurants, and resorts. Monroe says they produce 40,000 pounds of fish a year, with sales around $200,000. Last year, statewide fish farms produced 115,000 pounds of fish, with sales around $580,000. That's down 30 percent from the previous year, but similar to the rest of the country's fish farms. Still, West Virginia Commissioner of Agriculture Gus Douglas is optimistic that the industry holds greater statewide potential.

DOUGLAS: We can get up to a million pounds of production here without too much problem at all. We are always looking at resources and seeing if we can make a dollar out of it. And I have looked at southern West Virginia, I've looked at coal mining, and I think with planning this is the future of West Virginia.

CELESTE: Douglas estimates that the new industry will bring in as much as five million dollars a year in the future. Though the industry isn't providing a lot of full-time jobs right now, he believes that will change as the farms grow. And state agriculture officials say more jobs could be on the way, as other industries related to fish spring up. They also say that the over-harvesting of wild fish populations in the oceans could open up new commercial markets abroad, creating an even greater potential for West Virginia's southern coal mining region.

For Living On Earth, I'm Erika Celeste, in Lego, West Virginia.

Not-So-Wholesome Maple Syrup

CURWOOD: It's spring, finally, in New England, and the sap is rising and the maple sugar flowing. New Hampshire writer Lois Shea went sugaring recently and sent us this essay about the regional ritual.

SHEA: Jennifer and I were collecting sap in a small sugar orchard, on a perfect day in March. Spring's first blood rush was coursing through the sugar maples and spilling, plink, plink, plink, into galvanized buckets. We were engaged in that New England tradition of quaint self-reliance, of purity of spirit and of produce. We were making maple syrup. And, very stupidly, I was straddling a stone wall, standing shin deep in sloppy snow, with a five-gallon bucket of sap in one hand. I reached across the wall to lift another bucket off a tree. You know what happened next.

I slipped and ground my knee savagely into the stone wall, and let loose with a string of curses so vile that my dead Irish grandmother is probably still appealing to St. Peter on my behalf. Grimacing, but too embarrassed to admit to my wound or to my stupidity, I climbed in to the truck, and we bumped back down to the sugar house. The men were there, engaged in the time-honored New England ritual of standing around the evaporator and telling rude jokes.

My favorite: What's the difference between a New Hampshire sugar maker and a Vermont sugar-maker? A Vermonter goes along collecting sap. He comes to a bucket, lifts the lid, and finds a drowned squirrel inside. He looks all around to make sure nobody is watching, then he throws the squirrel away and pours the sap into his collecting tank. A New Hampshire sapper comes along and finds a drowned squirrel in his sap bucket. He looks all around to make sure nobody is watching, rings the squirrel out into his bucket, and then throws the squirrel away and pours the sap into his collecting tank.

Then we start on the Red Sox. Nomar is cussed, Grady Little is cussed. We reach way back and cuss Harry Frazee for selling Babe Ruth. The Yankees are cussed bitterly, and that was before anyone told a sheep joke, or Rogers Clemens and a sheep joke. You get the idea.

If the world ever knew what was said around New England evaporators, all in the process of making pure maple syrup. People buy maple syrup because it's the best tasting stuff in the world. And it is, to be sure, pure of content, the unadulterated distillation of early spring in New England. But people from, say, New Jersey or California, also buy something else when they lay down the $9.95 a quart. They buy nostalgia. They like to look at the jug on the breakfast table and imagine some sugarhouse in a little hollow somewhere, where green plastic tubing is ne’er to be seen, and a happy farmer rocks on his heels reciting Frost without irony, as the sap bubbles on through the night.

If they knew we were over here cussing knee injuries and the Red Sox, and making crude wildlife jokes, they might think us impure, somewhat less than quaint, and they might think our syrup tainted by association. So don't tell, but it's really not true about the squirrel.

[MUSIC: Allison Brown “The Red Earth” A World Instrumental Collection – Putumayo (1996)]

CURWOOD: And for this week, that's Living On Earth. Next week, we begin a two-part series on the environmental consequences of the civil war in Colombia. In the oil fields, for example, guerrilla groups are routinely blowing up pipelines. That's made for some harrowing experiences for workers caught in the crossfire.

MALE: We were getting the place organized to work where the pipeline had been broken. Then they started to launch cylinders stuffed with dynamite against the army, and we were right in between the army and the guerillas. We had been instructed to lie on the ground, facing down, and to keep our mouths open so that the explosive wave would not rip us apart.

CURWOOD: War and the environment in Colombia, next week on Living On Earth. And remember that between now and then you can hear us any time and get the stories behind the news by going to loe.org. That's loe.org.

We leave you this week at another stop in Lisboa. Michael Rüsenberg and Hans Ulrich Werner point their microphones at the rich soundscape of the Portuguese capitol, and blend the results into a form of urban poetry. This selection is called “Market on the New Bank.”

[SOUND OF MUSIC, TALKING: Earth Ear “Market on the New Bank” Lisboa! Earth Ear Records (1993)]

CURWOOD: Living On Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at loe.org. Our staff includes Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Cynthia Graber and Jennifer Chu, along with Tom Simon, Jessica Penney, Al Avery, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson, and Liz Lempert.

Special thanks to Ernie Silver. We had help this week from Katherine Lemcke, Jenny Cutrero and Nathan Marcy. Allison Dean composed our themes. Environmental sound art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our technical director is Chris Engles. Ingrid Lobet heads our Western Bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor. And Chris Ballman is the senior producer of Living on Earth.

I’m Steve Curwood, executive producer. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from The National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science; and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living On Earth Network, Living on Earth's expanded internet service. Support also comes from NPR member stations, and the Annenberg Foundation. And Tom's of Maine, maker of natural care products, and creator of the Rivers Awareness Program to preserve the nation's waterways. Information at participating stores or tomsofmaine.com

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth