August 15, 2003

Air Date: August 15, 2003

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Public Enemy #1

/ Jyl HoytView the page for this story

Ranchers and wild land managers in the West say their biggest threat these days is neither disease nor predators but weeds beating out plants that animals need for food. Jyl Hoyt reports on the latest techniques for fighting the scourge. (06:15)

One Silo at a Time

/ Anna Solomon-GreenbaumView the page for this story

Citizens in Takoma Park, Maryland are battling global warming at home. Anna Solomon-Greenbaum reports on one city’s efforts to cool the planet. (05:15)

Emerging Health Note/Nursing Home Sleep

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on research looking into ways to help nursing home patients get a better night's sleep. (01:20)

Almanac/Going Up!

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about Elisha Graves Otis' safety elevator. The inventor resorted to public demonstrations involving sliced hoisting cables to drum up business for his safety innovation back in 1854. (01:30)

Revolutionary Lighting

/ Cynthia GraberView the page for this story

Lighting accounts for 20 percent of all electricity use in the US, but a great deal of the energy used to produce that light is wasted as heat. Living on Earth’s Cynthia Graber reports on light-emitting diodes, a new energy-efficient technology that experts predict may take over the lighting industry. (06:00)

Light Up the World

View the page for this story

Dave Irvine-Halliday recently won an international award for using light-emitting diodes to bring light to homes throughout the developing world. He speaks with host Steve Curwood about his efforts. (05:00)

Ode to Dirt

/ Rebecca McClanahanView the page for this story

Rebecca McClanahan reads “Something Calling My Name”, her poem about a woman from Alabama who gave up her passion for tasting a bit of clay now and again to please her husband. (03:00)

Emerging Science Note/SoyScreen

/ Maggie VilligerView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Maggie Villiger reports on SoyScreen, a sunscreen made from soybean oil and bran. (01:20)

The Healing Land

View the page for this story

Author Rupert Isaacson grew up on stories of the Bushmen, the ancient tribe of hunters and healers in the deserts of Africa. As an adult, he journeyed through southern Africa in search of this elusive society. Host Steve Curwood talks with him about his new book, The Healing Land: The Bushmen of the Kalahari. (08:15)

Park Neglect

/ Sandy HausmanView the page for this story

Many of the famous features that draw people to America's national parks are in a sorry state of disrepair. They're remote--expensive and even dangerous to fix. Sandy Hausman reports from the sweeping heights of Glacier National Park in Montana. (07:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodREPORTERS: Jyl Hoyt, Sandy HausmanGUESTS: Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Irvine-Halliday, Rupert IsaacsonCOMMENTARY: Rebecca McClanahanNOTES: Diane Toomey, Maggie Villiger

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR - this is Living On Earth.

[THEME MUSIC]

I’m Steve Curwood. The incandescent light bulb is more than 100 years old, and it wastes almost all the power put into it. Now, light emitting diodes promise to revolutionize the lighting industry.

ZORPETTE: When you have the established giants, in this case General Electric, Philips, and Osram Sylvania all pumping significant quantities of money, of research funding into LED research, something is definitely happening.

CURWOOD: Light emitting diodes use so little power, they could be the answer for the two billion people who don’t have electricity today.

IRVINE-HALLIDAY: This is the first night in the entire life of all my five children that they’ve been able to read at night.

CURWOOD: Also, thin budgets in our National Parks mean summer tourists may be greeted by less than picturesque facilities. We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth, coming up right after this.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

FEMALE ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes form the National Science Foundation and Stoneyfield Farm.

Public Enemy #1

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Welcome to encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Today, noxious weeds are invading the American West. They're depriving domestic cattle and wildlife of food. And these exotic plants are also destroying recreational areas, choking out native grasses, and effectively killing off many species. The problem has prompted the federal government, environmental groups, and ranchers to work together against the growing menace in several localities. One place is Hell's Canyon on the Idaho/Oregon border. Jyl Hoyt of member station KBSX in Boise, Idaho reports.

[JET BOAT ON WATER]

HOYT: A metal jet boat holding a dozen people zooms up the powerful Snake River through Hell's Canyon National Recreation area. Oregon rises perpendicular to the east, Idaho to the west. When Hell's Canyon was set aside in 1975, no one imagined that one of the biggest threats to the place would be weeds.

[WATER]

KENDALL: Every value that this landscape was set aside for is going to disappear. This is a whole different enemy. This is war. This is war.

HOYT: It's an expensive war that's being fought all over the country: Kudzu in the East, leafy spurge in the Midwest, and many species across the West. The Federal Interagency Weed Committee estimates these alien weeds cost U.S. agriculture 20 billion dollars each year. Cattle won't eat most weeds, especially thorny ones like yellow star thistle, says rancher Ernie Robinson. So when weeds take over, cows can go hungry.

[BIRDS SINGING]

ROBINSON: Weeds is one of our biggest problems in cattle ranching. It's a constant fight. I know one ranch that used to run like 250 head of cattle, say 20 years ago, and they have yellow star so bad that, now, they probably, 50 head is about all they can run.

HOYT: That could be partly due to poor land management, but it's mostly because the weeds have no predators here. They left the predators behind in Europe where many weeds originally come from. Deer and elk don't like the weeds any more than cattle do. The weeds drive wildlife off protected lands and onto farms and even highways. Art Talsma of the Nature Conservancy squints at movement across the canyon.

[FOOTSTEPS IN TALL GRASS]

TALSMA: Wow. That's a five point mule deer buck, and he's in velvet, but he's almost acting like he's not wanting to walk through that star thistle. Look at that. He's high stepping.

HOYT: Weeds also degrade places that people like to visit, like national parks and bird refuges. Jason Karl who hikes, bikes, and works in Hell's Canyon, calls yellow star thistle "nasty".

KARL: It just rips and tears at your legs if you have shorts on. Like on a mountain bike ride, I've ridden through it, and your legs will be bleeding by the time you're done.

HOYT: Environmentalists, ranchers, and land managers struggle to outwit the weeds. They pull them up by hand and spray them with chemicals. And in one ingenious, low-tech solution, the Idaho Fish and Game's Jim White grew the right kind of bugs in a lab and then air-dropped them onto canyon terrain so rugged he didn't want to send in workers.

WHITE: And we took little coffee cups. We taped rocks to the bottom of them. We put the bugs in the coffee cups and when we flew over a star thistle patch, we would drop those coffee cups onto that patch.

HOYT: But it takes ten years for this so-called biological control to work. So soldiers in this war on weeds are borrowing strategies from firefighters, testing cutting-edge technologies to map new infestations when they're still small.

KARL: We can start mapping it right here at the GPS cursor.

HOYTE: This work used to be done with pencils on paper maps. The slow, inaccurate result wound up in some small office. Now, Karl holds a palm-sized computer with global positioning and information mapping software attached. He pulls up an aerial photograph of Garden Creek Valley. The cursor on the computer shows where we're standing.

KARL: Which is incredible, really, if you can think about it. You know, that you can locate yourself on the globe to within a couple of feet is a pretty phenomenal thing.

HOYT: As Karl walks around the outside of the weed patch, his hand-held computer draws a thick blue line wherever he walks.

KARL: Now, if I click this area and hit "Finish sketch" it basically completes this polygon that we just walked.

HOYT: Karl and other managers can now grab information from satellites circling the earth, quickly create their own weed maps in the field, and transfer them into office computers. Then, by punching a few keys, they can share all this information with ranchers and everyone else in the weed wars. SWAT teams are then sent to attack the weeds mechanically with herbicides or bugs.

They're using two other high-tech tools; aerial photos taken by small planes flying low over Hell's Canyon, and satellite images that show where weeds have not invaded. That way, land managers can more easily preserve them. The best long-term way to keep weeds out is to return native plants to the area. Art Talsma walks chest deep through a restoration project of native grasses.

TALSMA: And it has really taken on strong. It kind of gives us some hope that we can do quite a bit.

HOYT: When Anglos traipsed into this wild land with European seeds on their boots, they sowed this battle and they've been slowly losing it ever since. Now, with new tools and determination, they hope to win back some of the lost terrain.

For Living on Earth, I'm Jyl Hoyt in Hell's Canyon.

One Silo at a Time

CURWOOD: Global warming, as its term implies, is a global problem. And to address it, most scientists agree action must be taken on a global scale. The international agreement to combat climate change is the Kyoto Protocol. The United States is not taking part in the treaty, but efforts are underway here to curb greenhouse gas emissions. As part of an occasional series on how individual citizens are responding to climate change, Anna Solomon-Greenbaum has this story.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Just outside Washington, D.C., down at the public works compound in Takoma Park, Maryland, a few dozen people are watching their mayor cut a wide red ribbon to celebrate the town’s newest equipment.

[CHEERS AND APPLAUSE]

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: It’s not a new dump truck they’re cheering. It’s taller and shinier than that. It’s a brand-new silver silo filled with 21 tons of corn, sticking two stories up into the clear, cold sky.

BROWN: It’s a great big huge symbol about people doing things differently.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Eric Brown is one of ten Takoma residents who will burn that corn to heat their homes this winter. The corn kernels, he says, are clean, cheap, and warm.

BROWN: You know, they say that environmentalists, they’re the type who shiver in the dark and knit sweaters out of old mopheads. And boy, does this put the lie to that.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Standing nearby, Ashley Flora looks up at the silo. She and her husband just bought a corn stove last week.

Mike Tidwell’s son, Sasha, with corncobs in front of the corn-burning stove. (Photo: Mike Tidwell)

Mike Tidwell’s son, Sasha, with corncobs in front of the corn-burning stove. (Photo: Mike Tidwell)

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: And Flora says there might be indirect benefits.

FLORA: I told my husband, you know, congratulations, here’s your new exercise program. Our house is kind of up on a hill, so carting the corn up from the street up all the way to the stove, you know, who needs a gym membership? You’ve got corn to carry.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: One corn burner says his heat bill went from $1500 to $300 the year he switched from oil to corn. Others say they’re glad to be supporting the Maryland farmer who sells them the corn. He tries to farm it sustainably by using manure for fertilizer and letting the corn stalks compost back into the ground. Everyone says the silo will make burning corn more convenient.

[CORN KERNELS BEING POURED INTO BUCKET]

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Mike Tidwell squats below the silo and fills a bucket with corn. This is what he’ll do every couple weeks. Then he’ll drive it home.

TIDWELL: This is my house, come on in.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Tidwell directs the Chesapeake Climate Action Network.

TIDWELL: So, anyway, just lift the bag….

[CORN BEING POURED FROM BAG]

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: He says even after factoring in the fossil fuel that’s used on the farm or in transport, corn is far cleaner than natural gas or oil. It emits only as much carbon dioxide as it absorbs while it grew.

TIDWELL: When this thing is full it will hold 75 pounds of corn and that will go a couple of days, two days….

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: When Tidwell started burning corn last winter, he had to make frequent trips 40 miles out to the farm because he didn’t have enough storage space. He knew if he wanted corn-burning to spread, he’d have to bring the corn to the city. So he asked the stove’s manufacturer for a grant to purchase a silo.

TIDWELL: He saw the logic of that argument immediately and agreed to put the equivalent of a $3,000 grant toward the purchase of this.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Takoma agreed to put the silo on its property. Then Tidwell ran into a problem he hadn’t foreseen.

TIDWELL: I started calling local insurance companies and they said – what? You’ve got a corn silo in an urban area and people are going to come and get corn? No, we never heard of that. We can’t insure something that we have no established risk pattern for.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Ultimately, Tidwell and the other corn-burners gave the silo to the city and the city put the silo on its insurance plan. Tidwell formed a co-op so Takoma families could buy their corn in bulk, and now ten households own corn-burning stoves like his.

TIDWELL: There’s a very modern computer circuit board here on the side. This isn’t like an old cast-iron wood stove. This is a modern corn stove that is super-convenient. So, you have five heat settings on the side. We’ve got it on the lowest of five heat settings and it’s heating the house very, very well.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Maryland is encouraging corn burning by waving the sales tax for residents who buy corn stoves. Still, each one costs about two grand and another few hundred to install. But Mike Tidwell thinks the long-term savings will win all sorts of people over, even outside of places like Takoma Park, which is known for its progressive politics.

TIDWELL: I would not have bought a corn stove to begin with or worked this hard to create a co-operative and have an urban corn silo if I thought that this was just going to stay here in Takoma Park. We are early adopters and I think we are showing that this is a good idea, that it’s practical, it can be integrated into a modern lifestyle, it can save you money, and oh, by the way, it helps stop global warming.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Tidwell predicts the co-op will keep 100,000 pounds of CO2 out of the atmosphere over the next year and he expects many new members will join. There’s even room, he says, for a second silo.

For Living on Earth, I’m Anna Solomon-Greenbaum in Takoma Park, Maryland.

[MUSIC: Badly Drawn Boy “Above You, Below Me” About a Boy [Soundtrack] Artist Direct BMG (2002)]

Related links:

- Chesapeake Climate Action Network

- 1. American Energy Systems (corn stove manufacturer)

Emerging Health Note/Nursing Home Sleep

CURWOOD: Just ahead: the amazing power of lights that require almost no power to make them shine. First, this environmental health note from Diane Toomey.

[MUSIC: Health Note Theme]

TOOMEY: In recent years, there has been a move to make nursing home environments more pleasant and healthy by introducing quality of life enhancements. Those improvements include the addition of such things as plants and animals.

Now researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology want to help nursing home residents get a better night's sleep. They studied sleep disruption in 92 nursing homes, and found that when people woke up during the night, almost one-fifth of the time the cause of that disruption was loud noise.

To alleviate the problem, acoustical engineers working in several nursing homes are testing noise reduction technologies. They're hanging sound-absorbing panels in hallway walls, replacing noisy metal curtain hooks with silent ones, and wrapping sound-deadening blankets around motorized equipment.

Researchers are also trying to reduce television noise by imbedding speakers in headboard and bed pillows. The researchers will study the results, and they'll also examine what effect behavioral interventions have on sleep, such as increased daytime activity, and light exposure. Researchers say they think it will take a combination of behavioral and environmental interventions to improve the sleep of nursing home residents. That's this week's health note. I'm Diane Toomey.

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Cesaria Evora/Caetano Veloso "E Preciso Perdoar" Red Hot and Rio Verve (1996)]

Almanac/Going Up!

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. And – a little elevator music please.

[MUSIC: Ferrante & Teicher “On a Clear Day” Concert in the Clouds]

One hundred forty-nine years ago this week, Elisha Graves Otis hung out his shingle for the world's first safety hoist. Now, primitive elevators had been around for centuries. The earliest were lifted by muscle or waterwheel power. And then, steam hit the scene in the mid-1800s. But until Mr. Otis came along, these contraptions were risky. If the cable snapped, the elevator would plummet to the ground.

So, Mr. Otis invented a clamping mechanism of iron teeth to grab the elevator's guide rails if the hoisting rope snapped. But despite the safety modification, the elevator business remained slow. So Mr. Otis employed a bit of showmanship. At the 1854 World's Fair, he installed an open safety hoist inside the Crystal Palace in New York City, and climbed in.

As a crowd watched from four stories below, he reached up and sliced through the hoist rope with a saber. The audience gasped. But the safety ratchet bars automatically clamped and held. "All safe, gentlemen, all safe," he reportedly called down to the amazed crowd. After this demonstration, sales took off.

In 1857, a five-floor department store in New York City asked Mr. Otis to install the first passenger elevator. Before long, the Otis Elevator Company was doing a brisk business, heralding the age of the skyscraper and changing the urban landscape – and the music business – forever. And for this week, that's the Living on Earth Almanac.

[MUSIC]

Revolutionary Lighting

CURWOOD: Those of us who live in the industrialized world take lighting for granted. Reading lights, streetlights and headlights, even that little light in your refrigerator. About 20 percent of all energy used in the United States goes to power lights, and almost all of it is wasted. But now come the new light emitting diodes, or LEDs. These are far more efficient at using electricity for illumination. As Living on Earth’s Cynthia Graber reports, many people are calling LEDs the future of light.

MUSIC: “Baby dear, listen hear, I’m afraid to go home in the dark…”

GRABER: At the end of the 1800's Thomas Edison invented the light bulb and transformed the world. A New York Herald reporter described this scene in downtown New York in 1882.

MALE: In stores and business places throughout the lower quarter of the city, there was a strange glow last night. The dim flicker of gas, often subdued and debilitated by grim and uncleanly globes, was supplanted by a steady glare, bright and mellow, which illuminated interiors and shown through windows fixed and unwavering. It was the glowing incandescent lamps of Edison, used last evening for the first time.

GRABER: The incandescent bulb we use today hasn't changed much from Edison's days. An electric current goes through a filament. The filament becomes so hot it glows, producing light. But 95 percent of the electricity used to light up that incandescent light bulb gets wasted as heat. So scientists introduced a more efficient fluorescent bulb in the 1940s.

Fluorescents work by passing electricity through gas in a tube, which creates light. But the fluorescent bulbs never took over the residential market, because the harsh color isn't as pleasing as the warmer glow of incandescence. Now, scientists are developing something new that they hope will be both easy on the eye, and energy efficient. Secretary of Energy Spencer Abraham spoke about the promise of light emitting diodes, or LEDs, at the Energy Efficiency Forum in Washington, DC this summer.

ABRAHAM: And it is to fluorescent lamps what the automobile was to the horse and buggy. It's a revolutionary technological innovation that promises to really change the way we light our homes and our businesses.

GRABER: An LED is made up of layers of electron-charged substances. When an electric current passes through the layers, electrons jump from one to the other and give off energy. The amount of energy the electron gives off depends on the type of material used for the layers. And it's this energy that determines the color of the light. LEDs can be made in almost any color of the rainbow, and scientists say they will be significantly more energy efficient than either incandenscents or fluorescents.

Jerry Simmons is the head of the LED research team at Sandia National Lab in New Mexico. He says if the new technology penetrates half the entire lighting market within the next 15 years, it could greatly reduce total energy consumption.

SIMMONS: It's equivalent to about 20 billion dollars a year in electrical rate charges. It's the same amount of energy that's used by all the homes in the states of California, Oregon and Washington.

[TYPING SOUNDS]

GRABER: Color Kinetics is a Boston-based company designing creative uses for LEDs. An engineer types a few clicks at a keyboard and lights up pinpoints of red, green, and blue LEDs contained in a dozen four-foot-long plastic tubes. The color of light in the tube depends on how many LEDs are lit and in what combination. Kevin Dowling is Vice President of Strategy and Technology.

DOWLING: Our lights can produce 16.7 million colors. Although it sounds like a really big number, unfortunately humans can't actually discern that many colors. But the richness and saturation of the colors produces colors that are far more varied than almost anything else you see.

GRABER: The colors are mesmerizing. They glow as they change smoothly from yellow to magenta to turquoise to kelly green. Color Kinetics has used LEDs to design lighting displays for store signs, architectural lighting, sets for rock performances, even a bridge in Philadelphia.

DOWLING: There is a sensor at one end. When the train passes over the bridge, the lights actually chase the train. We've done other applications where as you walk by a wall, the wall starts to glow, and just phenomenal applications that we have not even begun to dream of.

GRABER: Color Kinetics is also selling light bulbs at art supply stores that change colors and effects with the push of a button.

LEDs have other practical uses, such as lighting heat sensitive material like food, or archival documents, because the fixture remains at room temperature. At a larger scale, LEDs are already taking over in applications such as traffic lights. As Jerry Simmons of Sandia National Lab points out, there is a tremendous loss of energy when a white incandescent bulb is covered with a red filter.

SIMMONS: So you would throw away all the light produced by that bulb, except for the red. With LEDs that are already producing only red, you don't have to throw any of the light away. So LEDs are ten times more energy efficient than the old incandescent traffic lights.

GRABER: And because LEDs are rugged and can last ten times longer than incandescents, they don't need to be changed as often. But while color LEDs have had a couple decades of research behind them, the substance used to create white light was discovered only six years ago. The next big challenge is to develop a more efficient, brighter white for residential and retail markets. Right now, white LEDs are only twice as energy efficient as incandescents. They're also very expensive. But researchers believe they can create white LEDs that are ten times as efficient, and one thousand times as long-lasting, making them cost effective as well.

Glenn Zorpette is executive editor of Spectrum, a technology magazine for the engineering industry. He says the real signal of the potential of LEDs is the investment by the lighting industry.

ZORPETTE: When you have the established giants, in this case General Electric, Philips, and Osram Sylvania all pumping significant quantities of money, of research funding into LED research, something is definitely happening. It would really seem that they see this as an important contributor to lighting in the future.

GRABER: The federal government is also developing millions of dollars to LED research and it's considering a new research initiative that will allot 50 million dollars per year over the next ten years to make widespread use of light emitting diodes a reality. For Living on Earth, I'm Cynthia Graber.

Related links:

- Sandia National Laboratories

- Color Kinetics

- LOE's "LEDs: The Future of Light"">

Light Up the World

CURWOOD: Worldwide, there are an estimated two billion people who don’t have access to lights. Their use of conventional lamps would require the construction of hundreds of new power plants. But one scientist in Calgary believes light emitting diodes can provide a far more efficient alternative. Dave Irvine-Halliday won the Rolex Award for Enterprise for bringing LED light to the developing world. He says the inspiration for the project came while he was hiking through Nepal.

IRVINE-HALLIDAY: There was a wee schoolhouse and I heard these children singing in the schoolhouse. So when I got down there, I popped my head in the window, which, of course, had no glass. And not only were there no children actually inside the school, but there were no tables, chairs, or teacher. And when I popped my head back out of the window, I noticed there was a lovely hand-painted sign above this window and it said ‘To you travelers, our children don't have any regular teachers, and if you'd like to kind of stay around for a couple of days and help our children, we would really appreciate it.’

I think at that moment, everything sort of came together. Because when I poked my head in the window, my first thought was how dark it was. I don't know. I honestly do not know why the thought suddenly struck me - is there anything that I could do as a photonics engineer to bring light to these folk, at least help the children with their education?

CURWOOD: Now why did you choose light-emitting diodes?

IRVINE-HALLIDAY: It just kind of struck me that if we were to produce light that was affordable and reliable and rugged, and also using very, very low power, we couldn't go along the standard routes, in other words incandescent bulbs, or even the much more efficient compact fluorescent lights. And because I deal with diodes basically every day of my life, though it's in kind of fiber optics, for some reason the thought just occurred to me, well, why don't we try LEDs?

CURWOOD: Now, why not use compact fluorescents in these villages? Don't they compare more favorably in efficiency to a white light light emitting diode?

IRVINE-HALLIDAY: I gave compact fluorescents a really deep look, but came to the conclusion that there was still approximately a ten to one difference in the amount of power or energy that I would need in order to light up a home to a useful level. This "useful,” the term "useful," I had to kind of define that myself. And when you find out how a light emitting diode actually emits its light, it emits it as a cone. You can actually direct it very efficiently to where you actually need the light to be, as opposed to lighting up the walls and the ceiling and the corners of the home. In a nutshell, the bottom line is you can light up a home to a very useful degree in the developing world, with a single watt of power. It's a bit more difficult to do that with a compact fluorescent. It just came down to the energy requirements, plus the reliability, and the fact that LEDs live for literally decades.

CURWOOD: What are the power sources that you've been using for these lights? If it only takes a watt, how do you get that one watt?

IRVINE-HALLIDAY: We've done it in three ways. The first method was what we called the pedal generator. That pedal generator, which kind of pumped out effectively around 40 watts or whatever, it would charge up five of these small 12-volt batteries simultaneously.

The second method we used was very small hydropower. The third way, which is probably the way that we're going to use mostly in the future, is good old solar power, solar photovoltaic cells.

CURWOOD: What stories have you heard? What have people told you about how all of this has affected their lives?

IRVINE-HALLIDAY: I think the first quote that really made a difference to me was in Sri Lanka, and we just lit our first village there. It was actually about one o'clock in the morning; we happened to have been out visiting people. We were coming back through the jungle and we saw this light, and we recognized it immediately as one of ours. So we went over, and the father was still up. He opened the door and showed us the children who were all kind of lying on a mat on the floor. And he said ‘This is the first night in the entire life of all my five children that they've been able to read at night.’ It's that kind of thing that, as I say, it kind of reduces you to tears almost, but if you ever needed a reason, which we don't, that certainly gives you it.

CURWOOD: David Irvine-Halliday is director of the Light Up the World Foundation. He recently received the Rolex Award for Enterprise for his work to bring light to developing countries. Thanks for speaking with me today.

IRVINE-HALLIDAY: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: For more information on light emitting diodes, go to our website, livingonearth.org. That’s livingonearth.org.

FEMALE ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation. Major contributors include the Ford Foundation, for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues; and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, for coverage of western issues. Support also comes from NPR member stations and Bob Williams and Meg Caldwell, honoring NPR’s coverage of environmental and natural resource issues, and in support of the NPR President’s Council; and Paul and Marcia Ginsberg, in support of excellence in public radio.

Related links:

- Light up the World Foundation

- Rolex Awards for Enterprise

- LOE's "LEDs: The Future of Light"">

Ode to Dirt

CURWOOD: Country kids play in dirt, dig in dirt, and sometimes love to eat dirt. Not all of them outgrow the urge. And that brings us to a poem by Rebecca McClanahan. She writes about one fictional southern woman who gave up eating dirt for her husband. It’s called "Something Calling My Name."

MCCLANAHAN: I tried to tell him. But he won't hear.Earl, I say, it's safe. It's cleanif you dig below where man has been,deep to the first blackness.I tell him. But he won't hear.Says my mouth used to taste like mud,made him want to spit.

I tried to tell him how fine it was.When I was big, with Earl Junior and Shad,I laid on my back, my belly all swelledlike the high dirt hillssloping down to the bankabove the gravel road by Mama's.And I'd dream it. Rich and black after rain.Like something calling my name.

I'd say, Earl, remember? That spring in Chicago,I thought I'd die, my mouth all tasteless,waiting for Wednesdays, shoeboxesfull of the smell of home.The postman, he'd scratch his head,but he kept on bringing. Bless Mama.She baked it right, the way I like.Vinegar-sprinkled. And salt.I'd carry it in the little red pouchor loose in my apron pocketand when the day got too long and dryand Earl home too late for loving,I'd have me a taste. It saved me, it did.And when we finally made it back,the smell of Alabama soilpoured itself right through me.I sang again, and things were finetill the night he leaned back and said"No More," his man-smells, all richand mixed up with evening. Right there,laying by me, he made me choosebetween his kisses and my clay.

Earl, I say, I've given it up.And right then, I have.But sometimes, on summer nights like thiswhen the clouds hang heavyand I hear that first rumble and the earthpeels itself back and the crust darkensand the underneath soil bubbles updamp and flavored, it all comes backand I believe I'd do anythingto kneel at that bankabove the gravel road by Mama'sand dig in deep till my arms are smearedand scoop it wet to my mouth.

CURWOOD: Rebecca McClanahan is a writer who lives in New York City. Her latest collection of essays is called "The Riddle Song and Other Rememberings."

[MUSIC: Badly Drawn Boy “Dead Duck” About a Boy [Soundtrack] Artist Direct BMG (2002)]

Related link:

Rebecca McClanahan’s website

Emerging Science Note/SoyScreen

Coming up: thousands of years of human history come alive through the present day voices of the Bushmen of the Kalahari. First, this note on emerging science from Maggie Villiger.

[MUSIC: SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

VILLIGER: Everyone knows it's important to protect your skin from the sun. Now scientists from the United States Department of Agriculture have developed an all-natural way to ward off those damaging rays. Researchers were examining the chemical structure of ferulic acid, an antioxidant that's found in the cell walls of oat and rice bran. They noticed that ferulic acid's structure is remarkably similar to the UV-absorbing chemicals currently used in sunscreens, and they discovered it in fact shared their sun-protective properties. But on its own, ferulic acid would be an impractical sunscreen, since it's soluble in water, and no one wants a sunscreen that easily washes or sweats off.

So the scientists figured out how to combine soybean oil and ferulic acid to form a molecule that absorbs UV rays and doesn't dissolve in water. They dubbed it SoyScreen. The product's manufacturing process is environmentally benign, since it relies on a low-temperature reaction helped along by an enzyme that can be recycled repeatedly.

Another advantage: SoyScreen breaks down in the environment and doesn't bio-accumulate like other chemicals currently used as sunscreens. The company licensing SoyScreen hopes to test-market cosmetic products containing the new ingredient by the end of the year. That's this week's note on emerging science. I'm Maggie Villiger.

CURWOOD: And you're listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Gary Stroutsos “I am Walking” Winds Of Honor Makoche (1996)]

Related link:

National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research site on SoyScreen

The Healing Land

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood, and coming up: the fiscal crunch faced by national parks. But first, as a child growing up in London, Rupert Isaacson thrilled to hear the stories his South African mother and Rhodesian father would tell him about the ancient tribe of people who lived deep in the African deserts. Tales of the Bushmen in the Kalahari, of stealthy hunters, magical healers, and a peaceful society seemingly frozen in time haunted Isaacson so much that he later journeyed to southern Africa to find the last of the Bushmen. He's written a book about his travels called “The Healing Land: The Bushmen and the Kalahari Desert.” Rupert Isaacson joins me now from Austin, Texas. Welcome to Living on Earth.

ISAACSON: Hello. Thank you very much for having me.

CURWOOD: Rupert, just who are the Bushmen?

ISAACSON: They are the first people of Southern Africa. They were there before anybody else. They're a small, golden-skinned people, with a slightly Asiatic cast to the face. They used to live everywhere in Southern Africa. But gradually, as people came down from the north, from central and east Africa and west Africa, bringing livestock maybe two to three thousand years ago, and then, of course, when whites showed up 300 plus years ago, the Bushmen found themselves in a kind of double squeeze. And they vanished pretty much, were wiped out or assimilated from any-- all the good areas of land, anywhere that had permanent water, anywhere that you could grow crops. And the last relic populations were by, say, a hundred years ago, really were confined to the Kalahari.

CURWOOD: I understand that you've brought some recordings from the bush. Let's take a listen.

[BUSHMEN TALKING]

CURWOOD: So, tell me about these sounds that they're making. Some of the sounds sound like they're kissing, and then they're clicking. What's going on?

ISAACSON: There's about six different clicks within the bushmen languages. There's many different languages. This is shunghua (ph.) that we're listening to now, and even I'm mispronouncing that. My click was a little too hard. It should have been like that kissing click. Shunghua. Not only are there these six clicks in the language -- which, ironically, have been bequeathed to some of the other southern African tribes that actually took land from the bushmen, like the Zulu, the (inaudible) and so on, the Bushmen originated it --they also have a lot of tonality. There's these hard ones, [click], as you say this kissing one, [click], the sound you might make to gee up a horse, [click]. Incredibly complex languages, and ancient. People think these go back at least 40 to 60,000 years.

CURWOOD: Rupert, please tell me about your first encounter with Bushmen. You went up to the Kalahari and you met two men. What were their names and how did they react to your presence?

ISAACSON: Their names were Benjamin Xishe and a man called Kaece. I'd been told you go to this place called Tsumkwe in Northeast Namibia in the Nyae Nyae area. You drive east towards the Botswana border, and after about 15 minutes you may or may not see these baobab trees sticking out over the bush, then you may or may not see this little track, depending on how overgrown it is. And if you do see it, and you drive as far as you can, it may or may not still lead to where this biggest baobab is. And if you get there, just make camp and the Bushmen will find you.

So, that's what I did. And I was with my then-girlfriend, now wife, Kristen, and there was this scrunch of feet on leaves and we looked around and two Bushmen had walked into the clearing. And immediately all my preconceptions got turned on their head, because there were two of them. One was a youngish guy, Benjamin, about my age, the other, an older guy wearing the xai, the traditional loincloth that these guys wear.

But the younger guy was better dressed than me. I mean, he was wearing relatively new Reeboks, and his jeans were certainly better laundered than mine. And he walked right up to me and said in perfect English, "Hello, my name is Benjamin Xishe. Welcome to Nyae Nyae, what are you doing here?" More or less. And I didn't realize until that point really how colonial my outlook was, you know, how much I wanted these guys to look like Bushmen. I wanted them to be picturesque. I wanted them to wear loincloths and skins.

Of course, he knew exactly what I was thinking, because he was dealing with this all the time when people would come into this area. And he ended up answering a lot of my questions in a very indirect, kind of elegant way.

But Benjamin himself explained to me, “Well, the reason I speak English like this is because I ended up at a mission school in Botswana when I was a boy. I now work as a translator for an NGO, basically here to deal with people like you who show up, to find out what do you want here. Are you just a tourist, are you a journalist? What do you want to do?”

CURWOOD: And so, what did you do?

ISAACSON: I, of course, was desperate to go hunting with them and he, of course, knew that I was desperate to go hunting with him, because everyone who shows up there is desperate to go hunting with a Bushman. So he was sort of wryly watching me, waiting for me to ask this. But then he sort of very casually said “All right, well, just, you know, let's go, follow me.” He whistled at his friend, and then we were into the bush, and then suddenly it was all very real. Benjamin and his friend were tracking over ground where I couldn’t see anything, I couldn’t see any tracks. From time to time I'd stop them and say what are we following? And they'd say oh, look, you see, the steenbok that we're following here, a bird passed over here about 15 minutes ago. You know, we walk on for 15 minutes very casually, and then suddenly he makes me get down. And there it is, within an easy small bowshot away, completely oblivious to our presence.

CURWOOD: And then what happens?

ISAACSON: Well, then he reaches back to the quiver that he's carrying on his back. And in that quiver are arrows with a poison on them made from a beetle larva, and it's absolutely lethal. There is no antidote. So he very, very slowly, very silently pulls it out, he notches it onto the bow, he gets up into a half-crouch, he leans forward and he lets fly the arrow. And the arrow makes its arc, comes down about two inches from the antelope's shoulder. The animal takes off. He missed.

CURWOOD: Now I'm wondering how much of a show they're putting on for you. I mean, how much of this is kind of like, oh, okay, the tourist is here, the journalist is here?

ISAACSON: I think in that particular instance he would have killed it if he could, but yes, that absolutely goes on. Because people-- film crews show up and say right, we want to see a hunt, we want to see a hunt now. Now, now, now. Here's some money, go out and kill us an antelope. You hear them talking about this and say, we don't want to go kill an antelope, we don't need to go kill. So they'll come up with a reason not to. And in a way, that's their prerogative, because they're the ones who are managing the game and the land. They know what they should take and what they shouldn’t take at any one time.

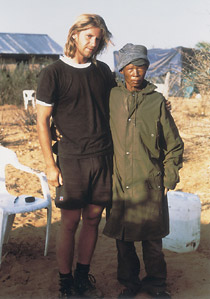

Rupert Isaacson with a Bushmen healer named Besa. (Photo courtesy of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.) Rupert Isaacson with a Bushmen healer named Besa. (Photo courtesy of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.) |

CURWOOD: It seems harder and harder for the Bushmen to remain isolated. And from what you've seen and observed, what are some of the ways that these people have adapted to the surrounding modern societies?

ISAACSON: They are very good at really being able to absorb anything from an outside culture, anything, whether it's mechanics, whether it's clothes, whether it's a boogie box, whether it's money, and to also keep the integrity of their own culture very intact. They are a much older and more resilient people, in some ways, than we are. It's much easier for them to flow in and out of our society and our culture, which they have to do all the time, whether it's dealing with a local government official, or a local tribal chief, or a tourist, or whoever they're having to deal with on that day. And there's a lot of theories about why they're so able to adapt in ways in ways that we find difficult. It's very hard for us to just go into the bush, for example. And I suppose that might come down to the hunting and foraging technology and mentality, where you're making use of every single situation that comes up. That allows for this ease and fluidity of dealing with and mixing with other cultures. CURWOOD: Rupert Isaacson is author of “The Healing Land: The Bushmen and the Kalahari Desert.” Rupert, thanks for taking this time with me today. ISAACSON: Thank you for having me. Related link:

Park NeglectCURWOOD: When he was running for president, George W. Bush pledged nearly five billion dollars to repair the nation’s parks that he said had deteriorated under the Clinton Administration. And even though today there are more visitors to the parks each year, percentage wise there are not more federal dollars going to repair and maintain these national landmarks. And now President Bush is being criticized for not doing enough. To assess the need, we sent reporter Sandy Hausman to Glacier National Park in Montana, a million acres of snow-capped mountains, deep green valleys, and clear, cold streams. You might call it calendar country. But observers say it’s also a poster child for the Park Service – proof of serious, even dangerous, neglect. [SOUND OF VISITOR ENTERING GLACIER] RANGER: How are you? MAN: Hello, I’m fine. RANGER: Need any current information? MAN: Yes, that’d be great, if we could get a brochure. RANGER: Here’s a newspaper. Our visitor’s center is in Apgar, two miles ahead. MAN: Okay, thank you very much. RANGER: Sure, thank you. HAUSMAN: Every year, nearly one and a half million Americans drive through Glacier National Park on a remarkable 50 mile road built in the 1920s and '30s. The Going-to-the-Sun Highway is considered an engineering marvel. It clings to the side of the mountain, rising from 3000 to 6600 feet above sea level to cross the Continental Divide. Building this road was such dangerous and delicate work; it probably wouldn't be done today. But, 21st century visitors are glad it's here. Greg Myers stopped to admire the view after driving in from Madison, Wisconsin on his Harley. MYERS: Definitely worth the 2,000 mile trip just to go up and down that hill once, put it that way. This is the second time we've taken it. And, it's gets better every time. You got to remember to watch where you're going, as well as watch the mountains. Otherwise, you end up in trouble. HAUSMAN: Right off the edge. MYERS: Right off the edge. HAUSMAN: Visitors here sometimes see big horn sheep, mountain goats, and grizzlies. Park literature warns tourists of the potential risk posed by bears. But there is no warning about what may be a more serious threat to public safety. [SOUND OF SPLASHING WATERFALL] HAUSMAN: Water is everywhere, eroding the ground under this road and setting rocks free above it. Several years ago, a Japanese tourist was killed when a boulder fell on his car. And Fred Babb, chief of project management at Glacier, says the risk is constant. BABB: Every day the Park Service has one gentleman that goes the entire length of the road just sweeping stone off the road. If he didn't do that, in a matter of a week the sections of the road would be completely covered by stone, and not passable. HAUSMAN: Snow is also a problem during Montana's long, cold winters. Steve Thompson, local program manager for the National Parks Conservation Association, leans over a cliff and stares at a pile of rocks below. THOMPSON: Looks like there was probably an avalanche that came through there not too long ago, and just took that retaining wall right over the edge. HAUSMAN: So, in the summer and fall, crews are busy restoring the road. [SOUND OF CONSTRUCTION GENERATOR] HAUSMAN: About a mile below the highway summit, two men are standing on a platform hanging over the edge of a cliff, suspended from a crane. Construction worker Bruce Wann says they are replacing the mortar in the guard wall. And this is the only way to reach it. WANN: And then we got guys on the ropes to keep them from swinging around if the wind comes up, which it does up here. And the other hazards we have to deal with are lightning. The crane is a giant lightning rod. And if we get a lightning strike in the area, then we have to shut down. HAUSMAN: All total, six men will need about a month to fix 150 feet of wall. One stretch of wall in one national park, one reason why park repairs can be costly. [SOUND OF LOBBY IN MANY GLACIER LODGE]

|

Going-to-the-Sun Road, Glacier National Park (Photo: NPS)

Going-to-the-Sun Road, Glacier National Park (Photo: NPS)