September 11, 2009

Air Date: September 11, 2009

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

A Fallen Czar

View the page for this story

The president’s green jobs czar, Van Jones, quit his post in the face of criticism from conservatives about statements he made before his appointment. Jones resigned, saying the controversy following him was distracting people from the real issues. Host Jeff Young asks Joe Romm, a political analyst at the Center for American Progress what his departure means. (06:00)

Belaboring the Climate Bill

View the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood asks United Mine Workers of America President Cecil Roberts about his union's position on the Waxman-Markey climate bill. (06:00)

California Air Officials Nix Polluting Dairy Energy

/ Amy CoombsView the page for this story

Some dairy farmers are investing in machines that turn gases from cow poop into usable energy. The technology keeps potent climate change gases out of the atmosphere. But Amy Coombs reports some California farmers are getting into trouble with air pollution officials. (07:20)

Naming Nature

View the page for this story

Biologist and New York Times science writer Carol Kaesuk Yoon talks with host Jeff Young about how the science of taxonomy conflicts with our everyday sensory experience of the world. Yoon’s new book is called Naming Nature: The Clash Between Instinct and Science. (08:20)

The Language of Landscape

View the page for this story

Living on Earth continues its series exploring features of the American landscape, based on the book Home Ground: Language for an American Landscape, edited by Barry Lopez and Debra Gwartney. In this installment, Donna Seaman explains the term "commons." (01:45)

REDD Path to a Green Planet

/ Bruce GellermanView the page for this story

Climate scientists say preserving the world’s tropical rainforests is the fastest, cheapest way to mitigate climate change. In the first in a special series of field reports, Living on Earth’s Bruce Gellerman explores the Brazilian Amazon. Researchers there are trying to increase the value of the standing forest. They hope to preserve the Amazon’s rich biodiversity and its ability to store carbon. (17:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Hosts: Steve Curwood and Jeff Young

Guests: Cecil Roberts, Joe Romm, Carol Kaesuk Yoon

Reporters: Amy Coombs, Bruce Gellerman

Contributor: Donna Seaman

[THEME]

YOUNG: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

YOUNG: I’m Jeff Young.

CURWODO: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Green jobs champion Van Jones leaves his White House post amid attacks from the right wing. Some in Congress say President Obama made a mistake in letting Jones go.

SANDERS: I was disappointed that the White House caved in to the kind of ferocious attack that took place against Van Jones. In fact, I think getting rid of Van Jones only whets their appetite, and certainly more will come.

YOUNG: And – as climate negotiators try to find ways to save the world’s tropical rainforests – we travel to Brazil to see the problem firsthand.

CARTER: When we first moved here to the west was all forest and we'd sit here in the evening, my wife and I, and there'd be waves and waves of parrots and macaws flying over. Today there's maybe five, ten. There's no more forest left. They tore it all down.

YOUNG: The fight to conserve the Amazon, and its carbon - and more - this week on Living on Earth! So stick around.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

[THEME]

A Fallen Czar

Before coming to Washington D.C., Van Jones promoted green jobs at the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights in Oakland. (Photo: Luxomedia)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood

YOUNG: And I’m Jeff Young.

Not long after President Barack Obama took office he excited environmental activists by making Van Jones a White House special advisor on green jobs. An African American trained as a lawyer at Yale, Mr. Jones built an agency in the Oakland, California area that took off with a campaign for green jobs.

CURWOOD: He’s a best selling author and, as Living on Earth listeners heard last year, an electrifying speaker.

JONES: The people who said we could have a financial strategy based on borrow and spend and bubble and bailout, they've had their turn. They've been totally discredited. It's our turn now. Green jobs now! Green jobs now!

CURWOOD: But as soon as Van Jones was on the job he was under attack from conservative commentators like Fox News host Glen Beck.

BECK: Van Jones, Van Jones, he’s our green jobs czar. What does that tell you? It says that the president has an agenda that is radical, revolutionary and in some cases Marxist.

YOUNG: The pundits dug into his past and found Jones once used rude anatomical slang to describe some Republicans. More damaging, he long ago signed a petition involving the families of victims of 9/11. Among other things it claimed the Bush White House had some prior knowledge of the attacks. Van Jones says he never saw that petition’s full text and not does agree with it.

CURWOOD: But a White House spokesman offered little support, and Van Jones resigned over Labor Day weekend. The administration’s critics had a victory and its environmental supporters had questions about why Van Jones was let go, and what it meant for the green agenda.

Independent Vermont senator and green jobs subcommittee chair Bernie Sanders says the White House should have fought back.

SANDERS: I was disappointed that the White House caved in quite the way they did to the kind-of ferocious attack that took place against Van Jones from the right wing echo chamber, from Fox and perhaps some other right wing commentators. I would have preferred the White House remained firm in supporting Mr. Jones because, in fact, I think getting rid of Van Jones only whets their appetite, and certainly more will come.

CURWOOD: The White House says Jones’s decision to resign was his own.

YOUNG: We asked Joe Romm for a little analysis.

Romm served as an assistant secretary of energy in the Clinton years and now blogs on clean energy for the Democratic think tank, Center for American Progress.

Romm says Van Jones fell victim to a larger -- and increasingly ugly-- political fight over the country’s energy future.

ROMM: The person who claimed credit on Fox News for taking him down, who was this Phil Kerpen from the Americans For Prosperity, you know, was very blunt that they are against the clean energy jobs message. And, you know, he said we need to put not just him but the whole corrupt green jobs concept outside the bounds of the political mainstream. The clean energy jobs message has been a centerpiece of this administration and I think the right wing saw Van Jones as the embodiment of that message and that was an essential reason why they went after him.

YOUNG: American for Prosperity – what do we know about that organization?

ROMM: Well, we know that it is a front group for billionaire polluters – I think it’s Koch Industries that has backed them. They used to a pro tobacco industry group that worked to defeat things like smoke free work place. And now they are pushing very hard to kill the clean energy jobs and climate bill that’s gonna be discussed in the Senate this fall.

YOUNG: What do you think of how the White House handled this?

ROMM: I wish that the progressive community including me had recognized earlier. It is very hard to know whether to take a guy like Glen Beck seriously. I mean he called President Obama a racist. During the clean energy bill debate in the house, he and this guy from Americans for Prosperity took out a watermelon. They said it was a watermelon bill because it’s green on the outside and red on the inside. And so they took out a watermelon and started eating it.

Before coming to the Washington D.C. Van Jones promoted green jobs at the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights in Oakland. (Photo: Luxomedia)

ROMM: It certainly has a connotation given that the attacks were on African Americans - Van Jones and on President Obama. So I agree with you – it has certain undertones. And it is absurd to say that advocating green jobs is somehow socialist.

YOUNG: What does this incident tell us about the sort of debate we can expect when the Senate does get around to turning its attention to energy and climate change?

ROMM: The polluting industries, you know, like big oil who have been backing groups like Americans for Prosperity, they are opposed to clean energy. And they want to keep us addicted to dirty energy. So, they have, you know, tens of millions of dollars to throw at this and make this very coarse debate. They’re gonna go after every single clean energy advocate and they’re gonna spread disinformation at town hall meetings and through mailings and phone calls. So this is gonna be a very tough battle. Remember we haven’t passed clean air legislation in two decades. And we’ve never passed a climate bill. And we’ve never passed a clean energy bill like the one that’s being considered. So, yes, this is gonna be an epic battle. The forces of status quo make a lot of money from the status quo. And they are gonna use it to block change.

YOUNG: Joe Romm blogs and climateprogress.org. Thanks very much for your time.

ROMM: Thank you.

|

**WEB EXTRA** Interview with Senator Bernie Sanders - Living on Earth's Jeff Young interviews Sen. Bernie Sanders on the resignation of green jobs czar Van Jones.

Related links:

Belaboring the Climate Bill

Coal has powered American growth since the industrial revolution. (Hazelton, Pa c. 1905. Photo by Unknown) CURWOOD: Even as Van Jones was being drummed out of the White House climate crew, coal company Massey Energy sponsored a million dollar Labor Day party and rally in West Virginia. The mission—to boost opposition to the Waxman-Markey Climate bill that has passed the House and awaits Senate action. Massey CEO Don Blankenship: BLANKENSHIP: Do you want a government that wants to shut down our coalmines? CROWD: No! MASSEY: Do you want a government that increases your power bill? CROWD: No! MASSEY: Do you want a government that gives your tax money to your overseas competitors? CROWD: No! MASSEY: Do you want a government that thinks they can change the temperature of the earth when they can’t balance their budget? CROWD: No! CURWOOD: There were plenty of coal miners in the crowd, but even though it was labor day, labor leaders didn’t speak. Massey is a non-union company and the United Mine Workers of America has supported climate legislation in the past. But the union has reservations about the Waxman-Markey bill, especially its timetable to get so-called clean coal technology on line. ROBERTS: Hi, how are you today Steve? CURWOOD: So how long did you work as a miner? ROBERTS: Six years. CURWOOD: Underground? ROBERTS: Yes. CURWOOD: What was that like? ROBERTS: Well, quite frankly, once I got used to it which took about two months, it was fine – just like going to work any other place and quite proud to have been a coal miner then and quite proud to be a former coal miner now. CURWOOD: And your dad was a coal miner. ROBERTS: Father was a coal miner. Both grandfathers were coal miners. And both were killed in coalmines. Never met either one of them. They were both killed before I was born.  Cecil Roberts, Jr., a sixth-generation coal miner, is the President of the United Mine Workers (UMWA). ROBERTS: Well, we try to express the feelings of our members, and I can tell you that the greatest fear is that if there’s a reduction in the amount of carbon that’s released into the atmosphere that means less coal being burned in the United States, which would mean less coal being transported, less coal being mined, fewer coal miners, fewer rail workers, fewer truck drivers. And that’s the fear – that they’re not gonna have a job or at least not have a job that provides the wages and benefits that they currently enjoy. CURWOOD: Let me just get one thing clear here. The United Mine Workers and coal miners that you represent do feel that there is a serious problem with climate change – that the science is real and that this is something that we’ve got to deal with. Do I have that right? ROBERTS: That would be correct. The union has never taken a position arguing against the science of climate change. We’ve engaged in the debate as to how to deal with it. We’ve spent lots and lots of time and resources of coal miners trying to deal with this issue in order to protect the jobs of the coal miners and, quite frankly, the jobs of many people, particularly in some of the hardest and most difficult economic areas of the country. CURWOOD: What needs to be in Waxman-Markey for your union to get behind it? ROBERTS: I think probably the most important thing to say about this bill is as it moves into the debate over on the Senate side is can we get to these types of reductions of 17 percent by 2020 and also develop this technology in such a short period of time and also deploy that technology onto the coal fired facilities that are in existence now and would be constructed into the future. We’re very much concerned we may not have enough time to do both. CURWOOD: Let me ask you this, Cecil Roberts. If the time table for the technology that would allow the burning of coal to continue while not endangering the planet, if that doesn’t come forward, would it not be in the best interest of America to indemnify those workers who aren’t able to continue working because this is really a special case? Would you see that? ROBERTS: I think what’s problematic here I believe is that we’re talking about miners who are earning a very good wage and benefit for their families currently. They have healthcare. They have pensions. We have 100,000 retirees. Then there’s about a four to one to six to one ratio of support jobs that go with every mining job, depending on what part of the country you’re in. This would be an enormous cost obviously if the government said, “well, we owe these people something.” And I certainly agree that the country owes a great debt to coal miners. I think if would be difficult to convince Congress, the government, to do this.  Coal has powered American growth since the industrial revolution. (Hazelton, PA c. 1905) ROBERTS: Well, I think that there should be restrictions, and I would point out one aspect of this climate change debate that does concern us. China has to do nothing here. They’re building a coal-fired power plant every week, by the way. And it’s almost the same in India. And they have no plans to stop that. And they start making all the products that we make here. American workers have a right to ask those questions and be concerned about ‘em. CURWOOD: Cecil Roberts, the President of United Mine Workers of America, thanks so much for taking the time with me today. ROBERTS: Well thank you for having us. [MUSIC: Martin & Johnson “Coal Mine Blues” from Birdie (Martin And Johnson 2007)] YOUNG: Coming up –- how names like whippoorwill and chickadee illuminate some universal truths. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

California Air Officials Nix Polluting Dairy Energy

More than a hundred dairies across the U.S. are generating electricity from cow waste. (Photo: Amy Coombs) YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young. CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. In recent years, many dairy farmers around the country have started capturing the gases from their cow manure, and converting them into energy. Using this renewable resource saves money – and copes with a problem - a win-win solution. But in the central valley of California, which has some of the worst air quality in the nation, these new methane digesters are sparking controversy. That's because they generate some pollution themselves. Amy Coombs has our story. COOMBS: At Fiscalini Farms outside Modesto, CA, agricultural engineer Nettie Drake is giving a tour around a state-of-the art, open-air barn. [SOUND OF BIRDS, COWS MOOING AND CLINKING] COOMBS: It has plenty of room for 1700 dairy cows to eat, drink and produce the stuff that green power is made of. [COW POOPING AND PEEING NOISES] COOMBS: Drake says one person’s cow waste is another’s commodity. DRAKE: Instead of calling it waste, because of the negative connotation of that, we actually call it nutrient because it creates a very valuable product, and that would be the electricity and the heat that we use as a renewable resource. [FARM SOUNDS] COOMBS: Fiscalini just built a methane digester to convert cow manure into electricity. The farm hopes to make some 100,000 dollars a month by selling extra electricity back to the grid. The first step is collecting the cow nutrient. [SOUND OF WATER MOVING THROUGH GATES] DRAKE: The funny thing about the cows is that we’ve been able to train them to defecate in the area where they eat and that allows us to use water to collect the waste.  The "Ferrari" of methane generators can't be turned on because of emissions guidelines. (Photo: Amy Coombs) [MOO] COOMBS: That methane, when burned in a generator, would make enough power to run the entire farm, plus 600 homes. But Drake points to the bright orange Caterpillar engine sitting silent. DRAKE: This is our big boy and unfortunately we cannot turn it on because they won’t let us. COOMBS: San Joaquin Valley air officials have blocked the farm from turning on their manure digester until they install air pollution equipment. Air official Dave Warner says digesters like this one produce nitrogen oxide, or NOX, for short. WARNER: Nitrogen Oxide is what’s known as a precursor to a couple of very important pollutants. Fine particulate matter, which when you breath in gets into your lungs and even your blood stream. It’s also a precursor to ozone pollution. Ozone pollution causes all kinds of respiratory problems from asthma to emphysema. COOMBS: NOX is made during combustion. Just like your car needs oxygen from the air to ignite spark plugs, so do diary generators. The problem is that air also contains nitrogen, and after combustion, this leaves behind nitrogen oxides. Warner and his colleagues have been trying to reduce NOX by eight tons per day just to meet federal health standards. He says he'll be darned if he'll let these dairy machines set that effort back. [TYPING] WARNER: I’ve called up a list of the dairies in the central region of the San Joaquin Valley and you can see it’s an extensive list. If every dairy that had the potential of installing this technology did so, they would create, according to our calculations, about five tons per day increase in nitrogen oxide emissions, virtually wiping out the eight tons per day reduction. COOMBS: It’s a sticky issue. Dairy generators emit NOX. But they also reduce greenhouse gases. They prevent the greenhouse gas methane from being released. Methane is 20 times more powerful a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. Plus since digesters make renewable electricity, they reduce the need for dirty power, like that from coal. But Warner says climate change is out of his jurisdiction. WARNER: The governing board of the air district has made it very clear that when these trade offs between green house gas emissions reductions and nitrous oxide increases are there in front of us, we are going to choose on the side of protecting the health of the people of the San Joaquin Valley. COOMBS: So as of last January, most dairies had to add an extra device to their manure digesters to capture NOX. [PUMP SOUNDS] COOMBS: At another nearby dairy, the Gallo Dairy, manager Carl Morris says that's been difficult. [SOUNDS OF TINKERING WITH TOOLS] COOMBS: He is replacing his eighth of these new pollution control devices.  Regulators require pollution-capturing technology called catalytic controls, but dairy gas is hard on the system. The device on the right awaits installation. The Gallo Farms has burned through eight devices so far. (Photo: Amy Coombs) COOMBS: This farm had been making electricity from methane for five years. But ever since they installed the new pollution controls, their digester has been down. [SOUND OF SQUISHY FOOTSTEPS] COOMBS: The farm's manure piles up in a giant 7-acre pond. Carl Morris says you can actually walk on the pond, because it's covered by a thick black plastic tarp strong enough to hold our weight. [SOUND OF FOOTSTEPS] COOMBS: You can feel the methane bubbles pushing up underneath the plastic. MORRIS: Once you get up here you are actually walking on the gas. There’s so much gas in this area that it’s supporting your weight. [SOUND OF FOOTSTEPS] MORRIS: We treat that gas and use it to power our generators, which produce 700KW of electricity.  The Gallo Farm's digester spans seven acres. Naturally occurring bacteria release methane as they break down cow waste. (Photo: Amy Coombs) [PUMP SOUNDS] COOMBS: Back at the Fiscalini Farms, you can feel the tension. The owners thought they’d be earning money from their clean electricity months ago. DRAKE: We have talked often about if we had known what we were getting into doing this project we would have never done it. And that’s sad. COOMBS: The farm had to spend $100,000 for the device. That's after $3 million they paid for the manure generator. DRAKE: The regulatory agencies that are requiring this don’t even know if the technology is going to work, it has not even been tested. Yet we were forced to spend the money putting it in. COOMBS: San Joaquin air officials admit that all the kinks haven't been worked out in adapting the pollution controls to dairies. They were designed for designed for landfills and sewage treatment plants. But air official Dave Warner says the point is the Valley cannot afford any increases in NOX. One out of five children here takes an inhaler to school. WARNER: We not going after dairies in any way – we are applying a very stringent rule to dairies just as we apply it to all other sources of air pollution in the San Joaquin Valley.  More than a hundred dairies across the US are generating electricity from cow waste. (Photo: Amy Coombs) [TINKERING SOUNDS] COOMBS: For Living on Earth, this is Amy Coombs in Modesto, California. [MOOING] [MUSIC: PM Romero “A Gathering Of Cows” from 900 Miles (Casterlidge Records 2008)]

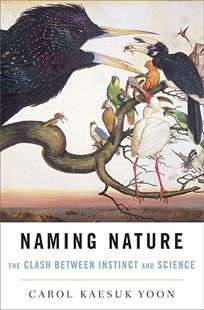

Naming Nature

YOUNG: Biologist and New York Times science writer Carol Kaesuk Yoon’s new book, Naming Nature, is a history of taxonomy. Now, the practice of putting Latin names to critters and plants might not sound like a setting for conflict and drama, but that’s just what she found. As her subtitle tells us, there’s a “clash between instinct and science.” Ms. Yoon discovered that as the science of taxonomy ordered things according to evolutionary ties it alienated those of us who relate to the natural world through instinct. YOON: So this basic way that humans have of seeing and perceiving the world is what creates the universals that are seen across all different people and across time in how people order and name life. It’s all – it all comes down to having the same basic sensory perception of life out there.  Carol Kaesuk Yoon YOON: Right. YOUNG: Go ahead. YOON: Okay, so the first pair, the first name is chunchuiket and the second name is maoozt. YOUNG: Okay. YOON: Okay. The second pair is, the first name is chichikia and the second one is katon. YOUNG: Okay. And pair number three? YOON: Teris and the second one is takaikit. YOUNG: Aha, now, okay. I have read your book, so I’ve already done this. [LAUGHING] YOUNG: But I remembered when I originally read this, these were my guesses: I thought – and I’m gonna mangle the pronounciation here – the chunchuikey sounded like a bird because it kind of reminded of chickadee, for example. And same with the next one: chichikia I thought sounded like – I honestly can’t remember how I guessed on the third one, so I can’t really say. YOON: Oh, I bet you were right. I bet you guessed takaitit YOUNG: Okay. So the right answers are… YOON: Chunchuikey, chichikia (sp) and takaikit. YOUNG: So I did pretty well. YOON: It’s probably what – yes, you did very well. YOUNG: And everyone does pretty well at this. That’s the deal, right? Everyone does pretty well at this. YOON: That’s what so interesting and so bizarre about it really. Over and over again in language after language and people after people, animal sounds are very often used as the actual name for the organism. YOUNG: So you would say this is the umwelt coming through here. YOON: Absolutely. Yeah, it’s part of what just from having a human brain and body and sensory perception of the world that we have that when we hear bird sounds it just makes sense to use to say “oh, you know, that’s that chickadee, that chickadee, chickadeedeedee.” YOUNG: It’s so obvious and yet it’s kind of profound that that’s what’s going on. YOON: That’s exactly it. It’s either – depending on how you look at it, it’s ridiculously obvious and not interesting or incredibly profound and very interesting which is obviously how I feel about it. And it’s this whole idea of actually being able to see how you see, seeing your frame of reference and stepping back and realizing that what’s around you and how you perceive the living world and how you name it, how you see basically what is out there is not just a matter of you taking in sensory data. It’s about this very human perception, a very human lens that you’re looking through that shows you what the living world is. It’s the human view of the living world. YOUNG: You also tell the story of these poor people who for whatever reason have lost the ability to name the things that they see in nature. Tell me about them? YOON: There have been people who have this trauma to the brain and then afterwards they can order and name nonliving things. So they can tell you what a flashlight is or a table or a chair, but they are unable to order and name living things, specifically and only living things. It’s evidence that there’s actually a physical spot in the brain that may be devoted to the ordering and naming of living things. YOUNG: So while neurologists were finding this out and anthropologists were out these interesting similarities about how folk taxonomies work, what was going on with the science of taxonomy? YOON: Well, around the same time, around the 80s there was a revolution going on in taxonomy. A man named Willi Hennig had figured out a way to order and name living things that was based much more on evolutionary relatedness than had ever been done before. And his followers were called cladists. This group of taxonomists was going around saying this is a whole new way to order and name the living world. And the problem was that once cladists started going through all of the organisms that people have long studied and thought about, they started discarding a lot of things that people didn’t want to see discarded. And one of the groups that they threw out was the fish. YOUNG: See this makes no sense. Why are there no fish as a group in taxonomy? YOON: Well, I can tell you why it bothers you. The reason it bothers you is because you’re umwelt is tell you “I know there are fish. I have seen fish. I’ve looked in the water. I’ve look on my dinner plate. I know there are fish.” But, in fact, the things that we call fish, if you look at them on an evolutionary tree of life they’re not a single cohesive group. YOUNG: So help me understand why did fish have to go away? YOON: Maybe the easiest way to understand it is with the example that cladists themselves used when they were going around trying to show everyone why fish couldn’t be a real group. So, if you try to figure out what say the evolutionary tree is of three organisms, so a salmon, a lungfish and a cow, it seems pretty obvious at first if you look at a salmon – it’s a fish. Everybody knows what it looks like. It has scales, it lays fishy eggs, it swims around in the water. Lung fish – same. And then there’s a cow, which everybody knows what it is. YOUNG: One of these things is not like the other. YOON: [laughs] That’s exactly right. And so you say, “well, it’s really obvious. The two fish go together and the cow goes off by itself on a separate branch of the tree.” And then what cladists proceeded to show people was it really isn’t that simple. So if you look at a lungfish, as the name suggests a lung fish has lungs. And it can breath air. And the thing about the lung fish is that like the cow, it actually came out of the lineage of fishes that made their way onto land and eventually gave rise to the vertebrates. And so if you make a correct evolutionary tree, what you find is that lungfish and cows are more closely related to each other. They more recently share a common ancestor with each other and they do with salmon. And so the problem is if you follow the rules that Willi Hennig and the cladists set out, if you go back to that original fishy fish ancestor and you look at all its descendents, you see the lungfish, you see the salmon, but you also see the cow. It’s in there. But if you don’t want to have all these other things that you never would think of as fish be included as fish, then you’re just gonna have to abandon the fish all together.

YOON: That’s what the cladists did. It’s a clean naked logic and it’s what scientists should be doing, it’s what people should be doing who are doing the evolutionary ordering of life. YOUNG: But this victory for science has not necessarily played out well for the rest of us, has it? YOON: No, I don’t think it hasn’t. I think the problem is that the more and more different that scientific ordering and naming has become from umvelt based naming, from just how things appear to us, and your umvelt tells you there is definitely such a thing as a fish. There is a group known as a fish. It’s one of the universal groups that everyone recognizes. If we seed all of the authority to saying what’s out there and how it’s grouped and what it’s named – which is basically a what of saying what it is – to science, and we leave ourselves only with this very, very rigid evolutionary view of the living world, we lose all these other ways of seeing things. And we lose our own way, our own most natural way, the sort of umvelt based way of seeing things in the living world, which is really important to have because it’s the way – it’s the most profound and sort of one of the deepest ways that people connect with living things, I think. YOUNG: Carol Kaesuk Yoon. The book is “Naming Nature: the clash between instinct and science.” Thank you very much. YOON: Thank you. [MUSIC: Daniel Lanois “O Marie” from Acadie (Daniellanois.com)] Related link:

The Language of Landscape

CURWOOD: From naming nature – to naming our landscape. The features of our American geography are the theme of our occasional series Home Ground. Today writer Donna Seaman defines a term dear to many lovers of the countryside – commons. SEAMAN: Commons. A common, or commons, is land that belongs to an entire community. More specifically, it is open land held in common by the people of a town for shared pasturage or the gathering of firewood. As noted in A Gazetteer of Illinois in 1834 by J.M. Peck, “A common is a tract of land…in which each owner of a village lot has a common but not an individual right. In some cases this tract embraces several thousand acres – the common attached to Cahokia extends up the prairie opposite St. Louis.” In her book Red: Passion and Patience in the Desert, Terry Tempest Williams notes that “most lands in the American West are public lands, a commons if you will, held inside a national trust: national forests, Bureau of Land Management lands, national parks, monuments, and refuges.” I say, these are the commons of a global village, preserved with common sense and commitment to the common good. CURWOOD: Donna Seaman is a writer and editor based in Illinois. Her definition of commons comes from the book Home Ground: Language for an American Landscape, edited by Barry Lopez and Debra Gwartney. [MUSIC: Brian Blade “Struggling With That” from Mama Rosa (Nonesuch 2009)] YOUNG: Just ahead – could part of the prescription for saving Brazil’s biodiversity be … snake oil? Stay with us - on Living on Earth. ANNOUNCER Support for the environmental health desk at Living On Earth comes from the Cedar Tree Foundation. Support also comes from the Richard and Rhoda Goldman fund for coverage of population and the environment. And from Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is Living On Earth on PRI, Public Radio International. Related link:

REDD Path to a Green Planet

A rainbow shines over the Amazon rainforest. (Photo: Marco Lima) YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young. CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. When negotiators gather in Copenhagen in December to consider a new global climate treaty, one major new element is what’s called REDD - Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation. The idea is to set a value on tropical forests, so they’re worth more left standing and capturing carbon than cut down. YOUNG: In the coming months Living on Earth will present a special series about REDD and the world’s tropical forests. Today, Living on Earth’s Senior Correspondent Bruce Gellerman has our first report, from the heart of the Amazon, as the river flows past Manaus, Brazil. [SOUND OF A BOAT ENGINE] GELELRMAN: The breeze feels great as the motorboat cuts across the Amazon even during Brazil’s dry winter season the air is hot and humid.  Marco Lima (right) talks with the boat driver as they cross the Amazon River. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb) GELLERMAN: Marco Lima, a fish biologist, joined our team as interpreter, driver and naturalist, as we set out on our month long journey to explore the Amazon. Today, it’s a short boat ride to see a unique Amazon phenomenon: The Meeting of the Waters. MARCO: If you look over here we can see the battle of two waters. The Amazon river trying to invade the Rio Negro and the Rio Negro backing off the Amazon waters. GELLERMAN: It’s a battle of different densities and water temperatures that’s fought out for miles. The black acidic Rio Negro is warmer than the cool, tan Amazon. The waters eventually merge into the mightiest of rivers. For more than 4,000 miles from the melting glaciers of the Peruvian Andes, the Amazon meanders wide and deep. Vegetation flourishes in the intense, tropical sun making the river basin the richest ecosystem on the planet.  The dark waters of the Rio Negro meets the tan Amazon River. The two travel side-by-side for miles without mixing. GELLERMAN: There are sharks and pink dolphins, stingrays and electric eels, giant piraracu and tiny but deadly toothpick fish. Three thousand species of fish swim in the Amazon, twice as many as in the Atlantic Ocean. One-third of the world’s species of plants and animals live in the river basin - wildlife found no place else on earth. Here one bush might contain more species of ants than the entire British Isles. [BIRDS PEEPING] MARCOL To understand the biological diversity of the Amazon is extremely easy. Between the big tributaries of the Amazon there is completely isolations. Most of our rivers they have at least five miles wide. And a river with five miles wide is an enormous river. Birds like toucans for example are not allowed to cross because they will fall in before they get to the middle of the river. And you say Marco they can swim. And I tell you no! Because predators are right there ready to eat what ever crosses the river. So many reasons why these areas get naturally isolated. [SOUND OF AIRPLANE] GELLERMAN: Even from the air, it’s hard to grasp the vastness of the Amazon. The river basin stretches across nine South American countries. It spans an area the size of the continental United States.  Areal view of the cerrado. The light green patches are soy and cattle fields. Dark green areas are forest reserves. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb) [AIRPLANE SOUNDS] GELLERMAN: In a single minute, the Amazon empties enough fresh water into the Atlantic to supply New York City for 60 years. The flow is four times that of the Congo River, ten times that of the Mississippi and 60 times as much as the Nile. [AIRPLANE SOUNDS] GELLERMAN: There are few paved roads. Rutted red dirt tracks connect small towns and villages. Isolated indigenous tribes live deep in the forest. Here you’re on your own. CARTER: You’re very remote. It’s not Kansas, you’re not Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz. It’s very rough region. GELLERMAN: John Carter pilots his four seater Cessna Skywagon to his ranch in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso. It means “Dense Wood” in Portuguese.  Swaths of green forest hug the river banks following a national effort to reforest riparian zones. White sand beaches in the river are evidence of the dry season. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb) GELLERMAN: Fifteen years ago when Carter settled here from Texas that was still an accurate description, but now this is cattle and soy country. [RANCH SOUNDS] CARTER: When we first moved here to the west was all forest and we'd sit here in the evening, my wife and I, and there'd be waves and waves of parrots and macaws flying over. Today there's maybe five, ten. There's no more forest left. They tore it all down. GELLERMAN: Illegal loggers came first, cutting the forests for their valuable hardwoods. Ranchers then torched the remaining trees and brush, converting the land into pasture for cattle. Then farmers came – and planted more profitable soybeans. As he surveys his land, John Carter says the destruction of the forest in this part of the Amazon basin has had a devastating effect on the weather and rainfall. CARTER: It really is not normal. It used to be it would rain in July and August and cause the trees to flower and it doesn't happen anymore. When I moved here said it’s going to rain next week.  Bruce Gellerman interviews John Carter as the rancher flies his Cessna over the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb) GELLERMAN: Transpiration: trees suck up water through their roots and release it through their leaves as water vapor. It rises and forms clouds that hover above the forest. When trees are cut down, there’s less transpiration, fewer clouds and less rain. [PEEPING BIRDS] GELLERMAN: it’s a cycle of destruction that feeds upon itself. Climate scientists call it: “die-back”. Deforestation leads to drought creating the conditions for vast wildfires, destroying the lungs of the planet. The Amazon basin, home to so much biological diversity is drying, and dying. And we really don’t know what’s being lost, because the Amazon River basin is not one but many ecosystems, and only a small fraction of what’s living here has been identified. Biologist Marco Lima: MARCO: Well, these places are amazing. Why not say that the transition forests are the big Pandora Box of the Amazon. GELLERMAN: And opening Brazil’s Amazon to development and agriculture in the 1960’s led to unexpected consequences. Today 75 percent of Brazil’s carbon dioxide emissions come from deforestation. [SOUND OF TRUCK COMING DOWN ROAD] GELLERMAN: Here along a dusty road near the town of Santo Antonio the dense, virgin forest to the north gives way to savanna. It’s a flat landscape with short trees, scrub brush and shallow ponds.  As water holes recede in the dry season animals congregate around ponds like this. That concentration of food makes these areas prime habitat for anacondas. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb) MARCO: In the cerrado or savannic environments like this we have a higher population of anacondas even more than in the forest. One thing is true for reptiles like anacondas if they see you first they will normally hide very well unless you are really an interesting dish for them. GELLERMAN: How big can the anaconda get here? MARCO: Twenty to thirty feet long, that’s easy to be seen. GELLERMAN: And they’re deadly? LIMA: An anaconda with 20 feet can kill a man like us. Easy. Control, individually break every single bone we have and swallow us. [ROOSTER CROWS] GELLERMAN: But more often - we swallow them. Anacondas, fat and lazy, rarely attack people. But the snake is a popular ingredient in traditional, folk medicines. [SOUND OF MARKETPLACE, MEDICINE MAN SPEAKING IN PORTUGESE] LIMA: (translation) This is the fat from the water snake anaconda. GELLERMAN: At an open air market in the city of Itaituba on the Trabajos River, a vendor sells a variety of potions made from Amazon products, including one with sukuri - Anaconda fat. He says it works wonders for coughs and wounds. [MEDICINE MAN SPEAKING IN PORTUGUESE] LIMA: (translation) It’s a great healer after you have some deep cuts.  A market vendor stands beside the medicine he makes from forest products such as anaconda fat. (Photo: Bruce Gellerman) MEDICINE MAN SPEAKING IN PORTUGUESE LIMA: (translation) Yeah, anaconda fat. GELLERMAN: How much do I take, what’s the dosage? [MEDICINE MAN SPEAKING IN PORTUGUESE LIMA: (translation) 1 teaspoon 2 times a day. GELLERMAN: I’ll take it. [MEDICINE MAN SPEAKING IN PORTUGUESE LIMA: (translation) Take it, it’s good. GELLERMAN: What do you got for male pattern baldness? [MEDICINE MAN SPEAKING IN PORTUGESE, LAUGHING] GELLERMAN: Don’t laugh. It’s estimated that a quarter of Western prescription drugs are derived from ingredients found in tropical forests. But only a small fraction of tropical plants and animals have ever been tested for medicinal purposes. The biologically rich Amazon could be worth tens of billions of dollars to drug companies, looking for compounds, like Anaconda fat. But what’s anaconda fat worth? According to Amazon forest scientist Niro Higuchi, it’s difficult to say and expensive to figure out. HIGUCHI: I have made some estimation to transform this anaconda fat into some product, a drug, you need at least almost a hundred million dollars in data collection. GELLERMAN: A hundred million dollars to study anaconda fat? HIGUCHI: Yes, to transform this fat into a drug. So this is something serious. This kind of study demand high technology, well trained people and a lot of money.  The front of an open air market in Itaituba, Brazil. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb) The agreement fell through at the last minute. Critics charged the company was trying to rob the nation of its biological wealth. [SOUND OF WALKING THROUGH THE JUNGLE] GELLERMAN: Suspicion of bio-piracy runs deep in Brazil - as deep as the Amazon forest itself. The Amazon economy was once based upon the rubber tree. Brazil provided the worlds supply of natural latex. But rubber tree seeds were stolen, exported and Brazil’s market monopoly was lost. Today, it imports rubber. HIGUCHI: My dream was to come to the Amazon, to study the Amazon Forest. GELLERMAN: For the past 30 years Niro Higuchi has been conducting field experiments in this patch of the dense forest north of Manaus.  Bruce Gellerman interviews Niro Higuchi about his research to place an economic value on standing forest. [SOUND OF BIRDS] HIGUCHI: Oh….now we’re getting into the jungle.. [BIRD CALL] GELLERMAN: What is that sound? HIGUCHI: It’s a bird the common name is jungle captain. GELLERMAN: Jungle captain. HIGUCHI: He announces we’re here. GELLERMAN: Ninety-eight percent of this forest – in Amazonas, the largest Brazilian state, is still standing. So far illegal loggers cattle ranchers and soy farmers have stayed out. But Higuchi is worried. That’s because for all its potential biological value. Right now, a piece of this Amazon forest with trees standing on it has virtually no commercial value. HIGUCHI: In the Manaus area you can buy one hectare of virgin forest for less than 50 dollars. GELLERMAN: Fifty bucks. HIGUCHI: Yes. GELLERMAN: It’s a bargain. HIGUCHI: A bargain. GELLERMAN: That comes to only about 20 dollars an acre for lush standing tropical forest. At that price, the forest is valuable only if its cleared and used for agriculture.  Paulo Moutinho is director of the climate change program at the Amazon Institute for Environmental research. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb) GELLERMAN: Paulo Mountinho is the Director of the Climate Change Program at IPAM, the Amazon Institute for Environmental Research. MOUNTINHO: The deforestation rate in the Amazon is so big now because you can not find alternative to use the forest in a sustainable way that have competition enough to face other types of land use like pasture like soy beans like other land use. That’s happened there because people not seeing that it’s possible you have a good life, make money keeping a standing forest. GELLERMAN: After 3 decades of studying the forest, scientist Niro Higuchi believes he has a solution. HIGUCHI: I believe in the short-term run if we combine forest management, wood products and carbon business we can keep this forest standing. GELLERMAN: To be sustainably developed forests must be carefully managed. Higuchi calculates a ton of hardwood per acre can be harvested each year - this would provide income for commercial loggers, increase the forest’s ability to capture and store more carbon, in turn making it more valuable in a potential carbon market. But protecting the forest’s biological diversity? That’s a different matter…  The canopy of the Amazon rainforest as seen from the top of an observation tower. (Photo: Marco Lima) GELLERMAN: Higuchi’s experiments demonstrate that even largely deforested plots of Amazon will grow back in 30 or 40 years. It may look green and lush but for a thousand years it won’t be the same forest. That’s because, when trees are cut down, the thin, nutrient poor Amazon soil loses its ability to sustain biological diversity. Paulo Moutinho of IPAM says no one is going to pay to protect soil. What’s needed is an economic incentive beyond biological diversity to save the standing forest. MOUNTINHO: Usually you are using a cultural argument, a biological diversity argument to save forest but I think that all these arguments are so important but not important enough to save a large area. We are talking about an area equivalent of all Europe.  Marco Lima, Bruce Gellerman, and Bobby Bascomb (left to right) One fifth of our annual worldwide emissions of climate changing CO2 is released when tropical forests are destroyed. Under the REDD mechanism developing countries with tropical forests would receive payments to keep their trees standing. Industrial nations would foot the bill, paying for their past and future carbon emissions. Forest scientist Niro Higuchi says REDD can work. It has to. HIGUCHI: This is our chance to do that. [SOUND OF WALKING UP STAIR AND WIND] GELLERMAN: In the dense Amazon forest north of Manaus researchers have built a 150- foot tall metal observatory. [WALKING UP TOWER] GELLERMAN: Producer Bobby Bascomb, biologist Marco Lima, and I huff and puff our way to the top, rewarded with a view of the forest canopy that seems to go on forever and a surprise. BASCOMB: Oh my God, look at that! Wow! A rainbow over the rainforest [SOUND OF HEAVY BREATHING] LIMA: Look at this 180 degrees rainbow. Amazing GELLERMAN: Climate negotiators in Copenhagen will need a rainbow like this: one with pots of gold at both ends. Guesstimates of the price tag for REDD range from 10 to 50 billion dollars a year. No one really knows how much - or how REDD will actually work. But time is short and the stakes are high. [SOUND OF BIRDS] BASCOMB: This is the first time I’ve ever seen both sides of a rainbow. GELLERMAN: A rainbow is both a biblical symbol of optimism and a divine promise that life on earth will never be destroyed.  A rainbow shines over the Amazon rainforest. (Photo: Marco Lima) [SOUND OF BIRDS] GELLERMAN: But now a man-made disaster threatens the planet and it is we who must find the will and act. And as the world considers what to do, the Amazon continues to flow relentlessly to the sea. For Living on Earth, in the Amazon forest. I’m Bruce Gellerman in Brazil. CURWOOD: Our story about carbon, biological diversity and the Amazon was produced by Living on Earth’s Bruce Gellerman and Bobby Bascomb with help from Marco Lima. [MUSIC: Severino Januario “Arraia de Santo Antonio” from O Melhor Pe-de-Serra (Movieplay Records]

|