January 9, 2015

Air Date: January 9, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Energy Policy in the New Year

View the page for this story

With the Republicans now in the majority in both chambers in Congree, President Obama could find his agenda stymied at every turn. Harvard Public Policy Professor Joe Aldy sits down with host Steve Curwood to discuss the Obama administration’s energy and environment policy outlook for this term, including the future of the Keystone XL pipeline, fracking regulation and the possibility for bipartisan collaboration on transportation. (12:05)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra gives host Steve Curwood a rundown on the newly-ascendent anti-science members of Congress, and looks back at the Montreal Protocol, a globally successful agreement that helped save the ozone. (05:15)

Conservationist Aldo Leopold’s Soundscapes Recreated

View the page for this story

Each morning, the conservationist Aldo Leopold took meticulous notes of the dawn bird chorus heard at his Wisconsin cabin. A team from the University of Wisconsin have used Leopold’s journals to recreate the soundscape that Leopold heard in 1940. Professor Stanley Temple talks about the project and Leopold’s influence on the environmental movement. (12:40)

The Sound Ring

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

Maya Lin’s Sound Ring — a large, wooden sculpture installed at Cornell’s Lab of Ornithology — plays the sounds of species and habitats that are on their way to silence. Living on Earth's Emmett Fitzgerald talks to John Fitzpatrick, Director of the Lab, about the structure and the significance of these endangered soundscapes. (08:40)

Branching into New Sounds

View the page for this story

Diego Stocco, a sound designer in Burbank, California, discovers the wealth of sounds he can produce by playing a tree. (04:00)

Sounds of Winter

View the page for this story

Listen closely. The frigid months of winter have a sound uniquely their own. As commentator Sy Montgomery points out, the cold and gray season’s bareness and rigidity help make its sounds vibrant. (04:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Joe Aldy, Stanley Temple, John Fitzpatrick, Diego Stocco

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Emmett Fitzgerald, Sy Montgomery

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. The new Republican majority on Capitol Hill is set to confront the White House on many environmental concerns, but there are some issues that may have an easier path to compromise.

ALDY: I think there’s a possibility that if the two parties can be creative in how we address transportation, we can have a longer-term transportation bill that addresses the financing needs for highway construction, but also delivers some environmental benefits.

CURWOOD: Also, at Cornell, a sculpture that plays recordings that evoke vanishing habitats.

FITZPATRICK: Really, what we love to do at the Cornell Lab is encourage people to hear the sounds that are lost in the background and work with our daily lives and individual behaviors to try to keep those sounds from disappearing.

[SOUND OF INDRI LEMURS]

CURWOOD: The sounds of threatened ecosystems and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

[THEME RETURN]

Energy Policy in the New Year

Aldy expects President Obama to, “come forward this year with a truly major, transformative regulation for the American power sector,” that will help curb greenhouse gas emissions. (Photo: Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. A new year, a new Congress with both chambers now controlled by Republicans, but that doesn’t seem to have cowed President Obama. Despite the limited Capitol Hill support, he seems eager to fight for a legacy that includes action on global warming. For example, a top priority for Republicans is getting a bill onto the President’s desk that would approve the Keystone XL pipeline for carbon intensive Canadian tar sands oil, but White House press secretary Josh Earnest left no doubt what would happen to the measure if it got there.

EARNEST: The fact is this piece of legislation is not altogether different than legislation that was introduced in the last Congress. And you'll recall that we put out a statement of administration position indicating that the President would have vetoed, had that bill passed the previous Congress. And I can confirm for you that if this bill passes this Congress, the President wouldn't sign it either.

CURWOOD: Those words don’t surprise Joe Aldy, a former Obama White House aide and now an Assistant Professor of Public Policy at Harvard University. He says there are other factors at play when it comes to decisions over Keystone.

ALDY: We’ve seen a lot of change in the North American energy system over the last four, five years that we've been debating Keystone, where now the United States has become a much more significant producer of oil domestically. We're also consuming less and less oil because of fuel economy standards here in the United States. We're also now in a period where we see oil at very low prices; prices we've really not seen since the Great Recession.

Transportation may provide an opportunity for bipartisan collaboration because of the nearly universal support for spending on roads, Aldy says. (Photo: Andy Withers; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Yes, you have to wonder how hard industry will be pushing for this thing when the price of oil is low as it is these days.

ALDY: I think when we look at the current oil market, there are a lot of people who have made investments, made bets in the more challenging oil to get out of the ground, and that includes the oil that's in Alberta. It also includes the shale oil development we've seen in the United States. Six months ago, when we saw oil at $100 dollars a barrel, those looked like good investments. Today, there's a lot of concern whether they can make money with current oil prices and likely near-term oil prices. So I think that will certainly influence how enthusiastic some will be about developing this pipeline and developing the resources in Canada.

CURWOOD: So, how much of this is a, well, frankly, a power struggle?

ALDY: I think a lot of Keystone has been about a power struggle between different political camps over a number of years that I think is larger than the impact it has on the environment or on jobs. We've seen this debate being played out as environment vs. jobs. I think it has a very modest impact on jobs. And I think there are other factors that will have a much bigger say on the environmental effect, such as: What is the price of oil and whether or not it's even economic to develop the resource, whether or not it's economic enough to move it out of Alberta by rail as a substitute to a pipeline which we've seen some of in recent years. These are going to be more important factors, what a couple of countries do in terms of addressing climate change more generally than whether we build this pipeline.

Domestic oil production has increased since the Keystone XL pipeline was first proposed over 6 years ago. (Photo: verifex; Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, Keystone, perhaps, is more symbolic than substantive.

ALDY: I think that is a very fair description.

CURWOOD: Now, the EPA has been rolling out some fairly far-reaching rules under President Obama's watch on CO2, really based on the Supreme Court decision a number of years ago. Remind us what we saw at the end of last year and what could be coming from them in 2015 in terms of new rules?

ALDY: So, the President has put forward, through the Environmental Protection Agency, a proposal to address carbon dioxide emissions from the nation's power plants. This is the largest source of carbon dioxide emissions in the United States, and it's where we have a lot of opportunities to significantly reduce our emissions, especially by switching from the dirty fuels like coal into either renewables like wind and solar or to natural gas. So the President's proposal has been out for comment. EPA received more than a million comments on the regulation. It's getting a lot of attention, and EPA is scheduled to this summer to publish a final regulation. And this rule then, once it goes final, will then prompt the states to start to design their plans on how to implement that rule to reduce the emissions of CO2 in their power sectors.

Oil prices have dropped to below $50 per barrel, calling into question the economic feasibility of the Keystone XL pipeline. (Photo: Philip Shoffner; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And once these rules come, what's the risk that they'll be a ton of lawsuits along with them?

ALDY: The probability is 100 percent that there will be lawsuits. In fact, there will likely be lawsuits filed from people on both sides of the issue, from both businesses and environmental groups that oppose this. You'll have some states that will be very supportive but may say they don't go far enough, and other states that will be very reluctant to implement the rules and may also try to challenge them as well. So, once the regulation is finalized, there will be a process to play out in the courts. We're likely to see a process play out in Congress as well. Congress does have the opportunity through the Congressional Review Act to review major regulations, and we've seen in the past how Congress has had a debate on climate-oriented regulations, the so-called "endangerment finding" that served as the basis for EPA to regulate carbon dioxide from automobiles and small trucks. You had a Republican in the Senate say, "Let's challenge this through the Congressional Review Act." That failed. I think you're likely to see a debate and an introduction of a challenge to the rule under the Congressional Review Act once it's finalized this year.

The EPA is currently evaluating public comments on President Obama’s proposal to regulate carbon dioxide emissions from power plants. (Photo: DonkeyHotey; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's talk about fracking. With the squeeze on coal-fired power plants, some folks are concerned that energy demand is shifting into natural gas. To what extent do you think the Obama Administration will look to regulate fracking in this next year?

ALDY: I think one area where the administration may move forward, and they've taken some action already to solicit input from the public and the industry, is to address the fugitive methane emissions associated with oil and gas activities. So, methane is a potent greenhouse gas, and there's a concern that sometimes when you're bringing oil and gas to the surface, not all of it stays in the pipe and some of it leaks out. And if you're drilling for gas, you don't really want a lot of fugitive emissions, because that's your money being leaked out in the air that otherwise you could sell in the market. So there is some incentive to try and minimize the extent of those emissions, but I think it's one area and it's really I think the last sort of single big category of emissions of greenhouse gases that the Obama Administration can tackle through existing authorities and in particular, under the Clean Air Act. The question on water impacts, local land use impacts—some of those end up being more of local kinds of issues, certainly on local land use, the impact on local infrastructure, something where the federal government really doesn't have much of a say or much in terms of authorities. On water, it's really kind of a mix between what the federal government can do and the states; we have very much a strong federal-state relationship when it comes to managing water. We may see some action there, but there may be more deference to what the states can do on the water front because the impacts do vary from state to state in a way that's distinct from the impact on air emissions where it's really sort of common regardless of where the drilling activity occurs.

A dense web of roads, pipelines and wellpads connect fracking sites to refineries and distribution lines. Aldy says that while the Obama administration may address the fugitive methane emissions associated with fracking, the administration will most likely defer to states for regulation of fracking wastewater. (Photo: Simon Fraser University; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: What do you think might be happening from the "unexpected" department in terms of legislation around the environment this year, legislation or new rules at the federal level?

ALDY: Well, I'm not sure there's a lot that's unexpected in terms of rules, in part, because of just the regulatory process works. Any regulation that goes through the federal government, first has to be proposed so that the public has an opportunity to comment on the regulation. Then, the regulatory agency takes that comment and then goes forward with the final regulation. On major rules, especially, say, the Environmental Protection Agency, it typically takes three to four years from beginning to end. So, if we knew that EPA was going to propose anything going forward that they plan to finalize before the end of the Obama Administration, it would already be out here. We'd already be well aware of it. So, I think in the climate context, the one that sticks out as they've talked about it, they've solicited feedback on different ways in which one can reduce methane emissions from oil and gas operations—they may propose in the near-term a regulation to address that, but other than that, I don't think there's a lot of surprises out there on what could be Executive Action just because the clock is starting to run out. In terms of legislation, this is something where I think it's potentially interesting because we've heard Republicans say they want to show how they can get things done, and the question is where are there opportunities for doing that. It's difficult to imagine a major environmental law reauthorization because I think the two parties are so far apart on the key issues, whether it's on clean air or clean water or the Endangered Species Act, but I think you might be able to see something on transportation. The other area where it may be interesting to see is whether or not there could be some kind of tax reform that may address things such as subsidies for fossil fuels. The challenge there is whether or not in reforming subsidies of fossil fuels, we also start to see the Republicans go after some of the tax credits that support wind and solar as well as energy efficiency investments. So that—I think that's one potential area if there's sort of traction on tax reform generally that we might see some reform of how the tax code affects our investment in different kinds of energy technologies.

The economic profitability of delivering tar sands crude to refineries by rail may affect the need for the Keystone XL pipeline. (Photo: Terry Cantrell; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: And what might be bipartisan about transportation?

ALDY: Well, we spend money on roads, and everyone likes to have money spent in their district on roads, so there at the end of the day, I think could be some support of an overall bill. The fact that the current bill runs out this year means there has to be some kind of legislative action on transportation, and the real question is whether or not there is something meaningful in terms of how we're going to finance road construction and mass transit investment going forward that may have a positive environmental benefit. Not just a positive environmental benefit, there's ways in which we can design the way we finance roads that also have a benefit in reducing congestion, which is, you know, people spending time sitting in their cars, increases frustration but also imposes costs on the economy. So I think there’s a possibility that if the two parties can be creative in how we address transportation, we can have a longer-term transportation bill that addresses the financing needs for highway construction, but also delivers some environmental benefits.

CURWOOD: So, Joe, what do you think the next couple of years are going to look like in terms of federal government dealing with environmental questions. We're going to see lots of fireworks, maybe another do-nothing Congress with lots of busy rulemaking veto-using President? Something else?

Power plants are the largest source of carbon dioxide emissions in the United States, and regulation targeting them can significantly reduce the US’ contribution to climate change. (Photo: Greg Goebel; CC BY-SA 2.0)

ALDY: On the energy and environment front, I'm not expecting much from Congress, but I expect the President to move forward in an aggressive manner with his existing authorities. I think we're going to see the President come forward this year with a truly major transformative regulation for the American power sector. I think that's going to set the foundation for the US to really have a meaningfully downward trajectory in terms of our greenhouse gas emissions, and I think it's something politically important for the President to use when he engages countries around the world to make sure that they move forward and undertake serious actions in their own countries to address greenhouse gas emissions. So I think that's going to be a major effort going forward for the President. I think it's something he's going to use as he works with other countries around the world in the run-up to Paris talks at the end of 2015, the next round of international climate negotiations, and I think that's really going to be - when we think about the action in Washington on energy and the environment - it's going to be there with the Executive Branch and it's going to be there with President Obama.

CURWOOD: Joe Aldy is an Assistant Professor of Public Policy at Harvard University. Thanks so much, Joe.

ALDY: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- White House briefing, which addressed its position on Keystone XL

- More on methane leaks from wells and pipelines

- Harvard Public Policy Professor Joe Aldy

[MUSIC: Ian Ethan “A New Day (The Narrow Way)]

CURWOOD: You can hear our program anytime on our website or get an audio download. The address is LOE.org, that’s LOE.org. There, you’ll also find pictures and more information about our stories. And we’d like to hear from you. You can reach us at comments@loe.org, once again, comments@loe.org. And you can call our listener line anytime at 800-218-9988; that’s 800-218-9988. Coming up: Bird songs of the morning recreated as the great naturalist Aldo Leopold heard them over half a century ago. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Andrew Bird “Fitz and the Dizzyspells” (Nobel Beast)]

Beyond the Headlines

Peter Dykstra estimates that the new Congress is the most anti-science crowd on Capitol Hill since the Scopes Monkey Trial ninety years ago, a major event in the debate over whether evolution could be taught in schools. (Photo: Юкатан; Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. It wouldn’t be the New Year, without a seasonal look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. He’s with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and the DailyClimate dot org, and he’s on the line now from Conyers, Georgia. Hi, Peter. A new year, and a change of control in Congress, what do you see there?

DYKSTRA: Well, Steve, the new Congress has hit town, and I wrote a piece to welcome them in. There are a lot of folks in Congress, veterans and newcomers, who have taken a firm stand against many forms of cutting-edge science. The last time the anti-science caucus was this strong may have been during the Scopes Monkey Trials ninety years ago. But that’s not the worst part of it: The folks who want to gut government research and deny climate change mostly won their elections by huge margins, suggesting that they’re virtually guaranteed perpetual reelection and jobs for life.

CURWOOD: Wow, the most anti-science crowd on Capitol Hill since the Monkey trials, which pitted creationism against scientific evolution? How did we get to this point?

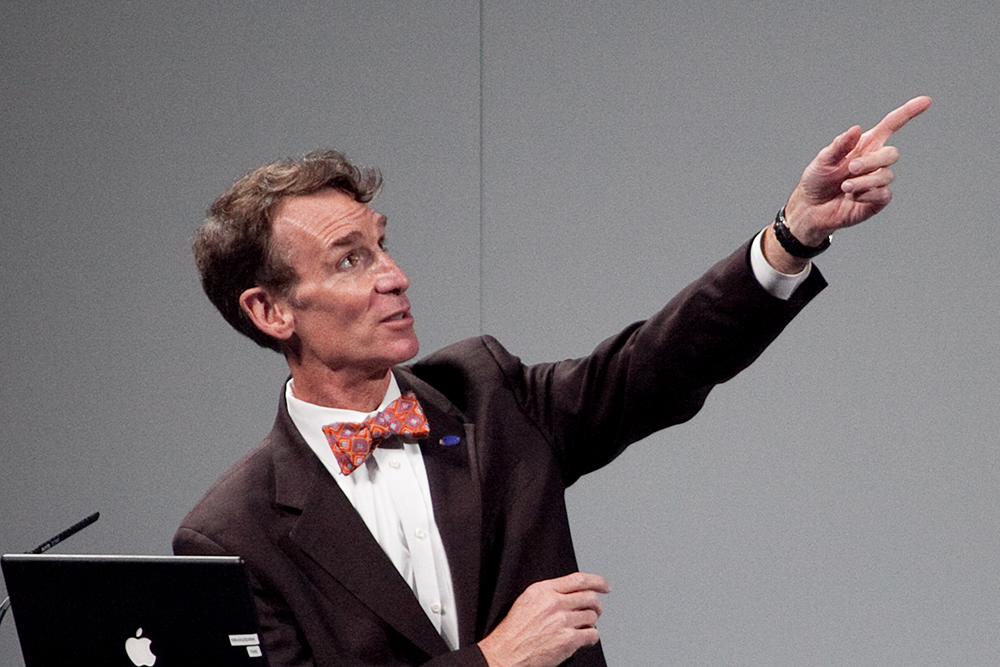

In 2014, Bill Nye ‘the Science Guy’ debated Representative Marsha Blackburn on whether or not climate change exists. Blackburn rejoins the U.S. House of Representatives this January, following a landslide victory over her opponents. (Photo: Ed Schipul; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, let me count the ways, and after that I’ll count how many members of Congress have, um, evolved. Redistricting, not to mention gobs of campaign cash, have had a particularly strong impact on the way Congress deals with science, environment and energy issues. And those easy election victories leave a strong suggestion that the Congressional anti-science streak isn’t going away any time soon, and maybe not in our lifetimes.

CURWOOD: So who are we talking about here? Give us a few examples.

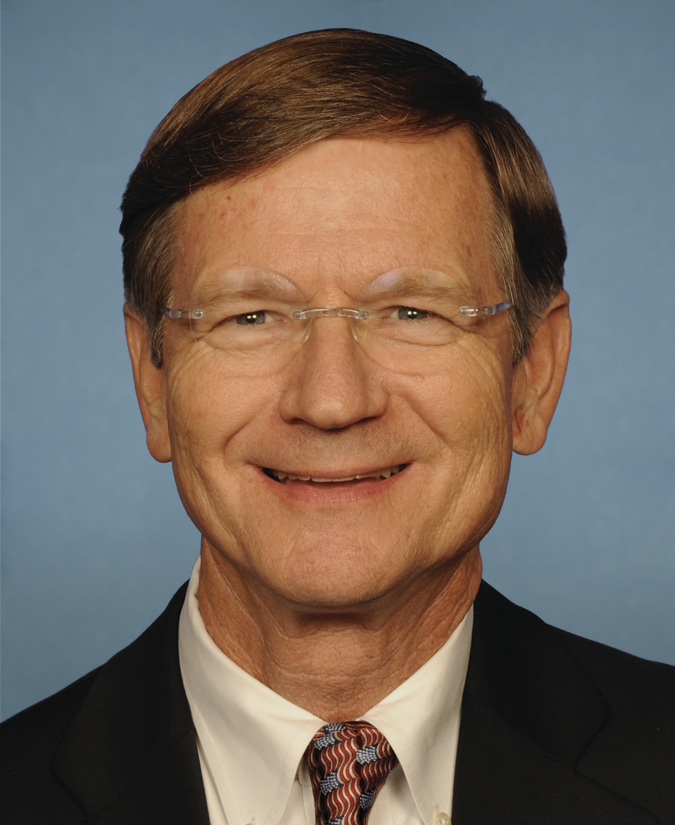

DYKSTRA: Martha Blackburn of Tennessee went on Meet The Press to debate Bill Nye the Science Guy on whether or not climate change exists. She’s also famous for leading a counterattack on energy-efficient light bulbs, and in November she got re-elected over token opposition by 44 points. She’s one of many who have no political reason to take climate science issues seriously. And then there’s Lamar Smith, Chair of the House Science Committee, he ran a series of hearings that attempted to grill climate scientists and horn into Federal science funding decisions.

CURWOOD: And so how did his Democratic opponent fare at the ballot box?

DYKSTRA: What Democratic opponent? The Dems didn’t run anyone in Smith’s San Antonio district, and he beat two third-party candidates with over 70 percent of the vote. His Science Committee Vice Chairman is Dana Rohrabacher of California, a staunch climate denier who reveled in raking the White House Science Advisor in hearings last year. Rohrabacher won by a comparatively meager 29 points.

CURWOOD: So the theme here, Peter, is that environmental science isn’t on the radar screen as a vote-getter for folks controlling discussions in Congress, huh?

DYKSTRA: Apparently not as an election issue. But wait, there’s more. Next is Joe Barton, famous for apologizing to the CEO of BP after its big oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. He said the government was trying to shake the oil company down. Barton is also from Texas and he won reelection to his sixteenth House term by a handy 25 points. And let’s look at a newcomer who ousted a powerful anti-science voice in the primary, but is poised to outdo him.

Lamar Smith returns to Capitol Hill as Chair of the House Science Committee, a position he’s used in the past to discredit climate science. (Photo: Connormah; Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: OK.

DYKSTRA: In Virginia, conservative college professor Dave Brat trounced another college professor by 24 points after ousting House Majority Leader Eric Cantor in the Republican primary. Brat believes climate change isn’t a big deal because, and I quote, “rich countries solve their own problems."

CURWOOD: Except that climate change is expected to hit the poor countries hardest, right?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, go figure. Now here’s your grand finale: Senator James Inhofe, the grandpappy of climate denial, won reelection by nearly forty points. He next runs, if he wants, in 2020, just before his 86th birthday.

CURWOOD: Well, you make it sound so bleak for science, but I suppose if you’re in the news business, at least bleak can be interesting. Let’s go on the environmental history tour for the week.

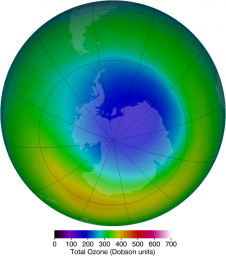

DYKSTRA: Steve, New Year’s Day marked the 25th anniversary of the Montreal Protocol. Negotiated in 1987 and taking effect on January 1st, 1989, the Montreal Protocol is an environmental treaty that works, that for the most part isn’t violated, and that after a quarter-century, is showing great results.

CURWOOD: Yeah, and the Montreal Protocol was the global effort to deal with the suddenly alarming news we all learned in the ‘80s that there were holes in the ozone layer.

New Year’s Day marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Montreal Protocol, which restricts the use of chlorofluorocarbons, chemicals that damage the Earth’s protective ozone layer. The European Union and 196 nations signed the Protocol and since then, the ozone layer has been in recovery. (Photo: NASA/Ozone Hole Watch)

DYKSTRA: Correct. We learned that chlorofluorocarbons – CFCs – and other chemicals were having a brutal effect on the ozone layer that protects us from ultraviolet radiation and skin cancer. CFCs were used as refrigerants and in aerosol sprays, and they were just about everywhere. But 196 nations and the European Union struck an agreement, largely effective to this day, to restrict and outlaw CFCs and other ozone depleting chemicals. Scientists say the ozone holes are well on their way to repairing themselves. But one of the most remarkable parts of this story about politicians paying attention to science is that two of the world leaders who pushed to make the treaty happen were conservative icons Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

CURWOOD: Hmm. Do the anti-science folks in today’s Congress know that?

DYKSTRA: If they do, Steve, it wouldn’t be a good fit in the political narrative on Capitol Hill these days.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is publisher of Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and The Daily Climate.org. Thanks, Peter, talk to you next time.

DYKSTRA: Okay Steve, thanks a lot, we’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Bill Nye ‘the Science Guy’ Debates Lawmaker on Climate Change

- Representative Lamar Smith’s page on Ballotpedia

- Representative Dana Rohrabacher’s page on Ballotpedia

- Representative Joe Barton’s page on Ballotpedia

- ‘8 Candidates We Can’t Believe Might Actually Win’

- Oklahoma Senate – Inhofe vs. Silverstein

- ‘The Montreal Protocol, a Little Treaty That Could’

[MUSIC: The Lumineers “Stubborn Love” (The Lumineers)]

Conservationist Aldo Leopold’s Soundscapes Recreated

Aldo Leopold and his dog. (Photo: Forest History Society)

CURWOOD: In the early morning before dawn, Aldo Leopold would sit on a bench outside his shack in Sauk County, Wisconsin, with a pot of coffee and a notebook. And as the sun rose, he took detailed notes as each bird joined the dawn chorus. Aldo Leopold was well known for his observations of the natural world, gathered in his 1949 book, A Sand County Almanac, that many consider to be some of the finest essays on the intrinsic value of nature.

Well, now we can actually hear the chorus that Aldo Leopold made note of in his morning journal, thanks to a team led by Stanley Temple, Professor Emeritus in Conservation at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Professor Temple joins us from Madison. Welcome to Living on Earth.

TEMPLE: Glad to be here!

CURWOOD: So, Aldo Leopold is an iconic figure to some, but for those of us who aren't as familiar with his work, who was Aldo Leopold?

TEMPLE: Aldo Leopold was probably the most influential conservation thinker of the 20th century. His career spans the first half of the 20th century and during that time he made some remarkable contributions. He began his career as a forester, but by mid-career he turned his attention to broader issues of conservation. And for most people, what they know best about Aldo Leopold, was that he left us, A Sand County Almanac. This was, essentially, the culmination of his life journey and it expressed his ideas about our relationship with the natural world.

CURWOOD: Professor Temple, you're a scientist by training, so how did you become so interested in this historical figure?

TEMPLE: Well, I was fortunate during my 32 years as a faculty member at the University of Wisconsin to have occupied the chair that Aldo Leopold once held. Not only was he a hero of mine personally, but because of my professional ties to him, I made it my business to learn more about him, and the University's archives has just a remarkable collection of his papers. And among those papers I discovered an unpublished manuscript that he was working on at the time of his death, in which he described the work that he had done over a decade of time studying the dawn chorus of birds, and in particular, how the sequence of songs plays out in the early morning light.

CURWOOD: What scientific observations did Aldo Leopold make about the morning bird chorus?

TEMPLE: He became fascinated with the sequence in which birds joined the dawn chorus and he was working on a hypothesis that the sequence was determined by light intensity; that each bird joined in the chorus, cued, you might say, by the intensity of the light. He bought one of the earliest light meters that were available, something that measured light intensity. He was very early in sort of posing this hypothesis. Others in the 1950s, when the technology was better, followed up and, indeed, verified that Leopold's ideas were correct.

CURWOOD: Please describe for us Aldo Leopold's dawn birding routine.

TEMPLE: Well, we could actually use his own words because he does describe it in nice detail in one of his essays in A Sand County Almanac called "Great Possessions":

"My daily ceremony, contrary to what you might suppose, begins with the utmost decorum. At 3:30am, with such dignity as I can muster, I step from my cabin door bearing in either hand a pot of coffee and a notebook. I get out my watch, pour coffee, and lay notebook on knee. This is the cue for the proclamations to begin."

CURWOOD: What gave you the idea to try and recreate the sounds that Aldo Leopold heard in his shack there in Wisconsin?

TEMPLE: Well, having read the unpublished manuscript, it struck me that you could put together, from his notes, all of the ingredients that would be required to recreate the sound that he was hearing. Well, it lay on the shelf or in the filing cabinet for many, many years and this past summer Brian Pijanowski, who's one of the leaders in the new soundscape ecology movement, invited me to give the keynote address at an NSF workshop that was held at the Leopold Center here in Wisconsin. And I thought this was the perfect incentive to actually go back and see whether indeed we could recreate the soundscape Leopold was listening to from his notes.

CURWOOD: What was your process?

TEMPLE: Well, the process was first, of course, to go through all of Leopold's notes and develop what you might say is a score. And then I enlisted the help of Chris Bocast, a graduate student here at the University of Wisconsin campus, who is an excellent audio engineer. And with the help of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology providing the actual recordings of the bird songs, we were able to put together a facsimile of what Aldo Leopold was listening to back on June 1st, 1940.

CURWOOD: I'm wondering what kinds of materials you were working with here; what did Aldo Leopold's notes look like?

TEMPLE: His notes were taken in a shorthand and what he noted was the time at which he first heard each bird joining the chorus. And he then took notes on how frequently he heard each species singing. So with that information, we could actually put the birds into the proper sequence and the proper timing of their calls but it went further than that. If you listen to the tape that we produced, in stereo, we've actually placed the birds in the soundscape in the relative positions that they should be in based on Aldo Leopold's territory maps. So the birds that appear to be coming from the left are birds of the field and prairie. The birds that are coming from the right are birds associated with the woodland and the birds in the middle are the ones associated with the edge in between the field and the woods.

CURWOOD: We’re going to play a clip from your soundscape now. Please, identify some of the sounds for us as we listen.

[ROBIN SINGING]

TEMPLE: Starts off with the American robin, an early riser.

[BIRD CALLS UNDER THE DISCUSSION]

TEMPLE: You can hear some birds in the distant background but the next bird to join is a field sparrow.

[TRILL OF FIELD SPARROW]

CURWOOD: That trill is the field sparrow?

TEMPLE: That's the field sparrow. We paid attention to the birds that were very close to Leopold, the ones that, as he said, he paid attention to. The next bird you're going to hear is an indigo bunting.

[CALL OF INDIGO BUNTING AND DISTANT CROWS]

TEMPLE: You can hear crows in the background.

CURWOOD: Good thing they were in the distance. They can be pretty loud.

TEMPLE: Yeah!

CURWOOD: Now, is this a compression of time or is this in real time here?

TEMPLE: We did compress the time; we didn't compress the bird songs. What we did we compressed the intervals between each bird's calls, but we compressed them proportional to Leopold's notes. So we actually compressed the first half hour of the day into five minutes. It still sounds pretty much like what it really does sound like. Just not quite so much down time between calls.

[MORE BIRD CALLS]

CURWOOD: Now who else has joined in here?

TEMPLE: The wood pewee comes in followed by the song sparrow and gray catbird. They start to pile on pretty quickly about this point.

[CALLS OF CATBIRD]

CURWOOD: OK, who's that?

TEMPLE: That's a catbird, sounding like a cat mewing.

CURWOOD: So what does the land around Aldo Leopold's shack look like today?

TEMPLE: Well, it's undergone quite a transformation since 1935 when Aldo Leopold purchased this worn-out farm that had almost no vegetation on it to speak of. He and his family spent many thousands of hours planting prairies, planting trees, and today, of course, what you see is a fairly mature ecosystem, and because of that the birds you hear today are a slightly different blend of birds, mix of birds, than Leopold was listening to. There are certainly more species in the dawn chorus today than there were in Leopold's time because of the habitat that Leopold and his family created for them.

The Aldo Leopold Center (Photo: Rebecca Brown)

CURWOOD: So we're going to play a clip now of the dawn sounds around the cabin taken from this summer. Let's have a listen.

[BIRD SONGS AND TRAFFIC SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: Well, there are a lot more birds there but it's pretty hard for me to hear them.

TEMPLE: That's right. But what you do hear is the traffic from the interstate.

CURWOOD: How do you think Aldo Leopold would respond if he could hear the morning soundscape that you recorded in 2012?

TEMPLE: Well, I think Leopold already gives us a hint that he was, to some extent, offended by the sounds of humanity that were impinging on the natural sounds. I'm going to read just a couple of sentences from another of his essays from A Sand County Almanac called "Too Early," in which he talks about arriving very early in a duck blind in a marsh.

"To arrive early in the marsh is an adventure in pure listening. The ear roams at will among the noises of the night without let or hindrance from hand or eye. Like many another treaty of restraint, the pre-dawn pact lasts only as long as darkness humbles the arrogant. By breakfast time comes the honks, horns, shouts, and whistles of an awakening farmyard and finally, at evening, the drone of an unattended radio."

So Leopold was well aware that the sounds of human beings were intruding on the natural sounds. So I don't think he would be surprised. I think he might have been certainly offended by the fact that the interstate highway came so close to his beloved shack.

CURWOOD: What's your favorite passage from A Sand County Almanac that you would feel comfortable reading right now that captures Aldo Leopold's thoughts on nature?

TEMPLE: Well, I think it's one that many people who are conservationists are aware of. It's one that gets quoted fairly often:

"If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part of it is good, whether we understand it or not. If the biota in the course of eons has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering."

I think you could apply that golden rule of Aldo Leopold's to the problems of soundscapes being polluted, if you will, by human-generated noises.

CURWOOD: Stanley Temple is a Professor Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin and a senior fellow at the Aldo Leopold Foundation. Thank you, sir.

TEMPLE: You're very welcome.

Related links:

- Stanley Temple recreated a dawn chorus soundscape likely heard by Conservationist Leopold

- Digital Archives of Aldo Leopold and his notes at the University of Wisconsin

- Aldo Leopold’s “A Sandy County Almanac”

- Stanley Temple at The Aldo Leopold Foundation

[Music: Jenny Scheinman “A Ride With Polly Jean” from Mischief And Mayhem (Jenny Scheinman Music 2012)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: Sounding the alarm for disappearing natural landscapes. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth – stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: William Coulter & Friends “Citi Na GCumman” (Celtic Sessions)]

The Sound Ring

An Indri lemur hoots its clarinet-like song. (Photo: Jeremy Oldenettel; CC BY-NC-SA Generic 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[SOUND OF LOONS]

CURWOOD: Thirty or so years ago, ornithologists and bird lovers worried that habitat loss and human development might silence forever the haunting call of the common loon in the Northern US. But scientists and citizens worked hard to help the bird recover, and though the loon population continues to decrease, it’s now thought to be less threatened. Still, some sounds of the natural world are at risk of disappearing forever, and that’s the focus of The Sound Ring, a sculpture of wood and speakers created by Maya Lin. It’s installed at the visitor center of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in Ithaca, New York, where John Fitzpatrick is Director of the Lab. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Emmett Fitzgerald.

FITZGERALD: So, John, tell us a little bit about this project. Whose idea was it, and how did you all get started?

The Common Loon population is beginning to stabilize thanks to the help of citizens and scientists. (Photo: Eugene Beckes; CC BY-NC-SA Generic 2.0)

FITZPATRICK: The project was an inspiration of Maya Lin’s, and she had from the very beginning this wonderful idea of a nine-foot-high beautifully elegant, walnut ring. It's actually eight speakers, and as you hear the world come to life from this, you're lost in the simplicity of what you're looking at and really what comes through are these sounds.

FITZGERALD: So, now you've chosen soundscapes from really all over the world. How did you make the decisions about which soundscapes to feature?

FITZPATRICK: Well, we chose sounds that have special meaning with respect to declining biodiversity. A lot of times people think that the endangered species story is a story about individual species, but really the species are indicative of a much broader issue in the environment.

FITZGERALD: Yeah. Let's listen to some of the soundscapes now, and as we play this tell us what we're hearing.

[SOUND OF PETRELS]

FITZPATRICK: Here we are on Round Island not far from the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. These are flying all around us, these amazing Gadfly petrels, called the Herald Petrel or Trindade petrels. These are seabirds that breed on tiny little islands around the world.

A Herald or Trindade Petrel (Photo: Pablo Caceres Contreras; CC BY-NC-ND Generic 2.0)

[PETREL SOUNDS CONTINUE]

Many of these petrels are actually extinct already or on the verge. This particular one is a great mystery because it's actually several different kinds breeding on Round Island. Petrels are colonial breeders, and so they can actually nest in quite dense colonies. And they have burrows in the rocks. So as they're flying overhead, they're actually sort of circling around and occasionally actually popping right inside, and then a few of them are actually calling from inside the burrow. Being on the ground in very simple habitats—when rats or cats are introduced to those islands, they go into the burrows and eat the eggs, eat the chicks and even occasionally take the adults. So the populations of many of the world's petrels are endangered.

[PETREL CALLS END]

An Olive Sided Flycatcher living up to its name. (Photo: Mike’s Birds; Flickr CC BY-SA Generic 2.0)

FITZGERALD: So that was an island habitat but there are dangers on large continents as well. Let's check out a forest. Can you walk us through this next soundscape?

[SOUNDS OF FOREST WITH OLIVE-SIDED FLYCATCHER CALLS]

FITZPATRICK: We're in western North America here. We're in the foothills of the Eastern Sierras actually. Oh, there's the "quick three beers" [song] of the Olive-sided flycatcher, which is perched at the very top of the conifer trees.

[CALL OF THE COMMON NIGHTHAWK]

FITZPATRICK: There's the boom of the Common Nighthawk, that who-hoo. What they're doing is they’re fly up pretty high and then they take a nosedive straight down towards the Earth and then at the last minute they stick their wings out and then they whoosh back up using their wings and they're making the booming sound with the primary wing feathers. They're sort of announcing themselves and advertising for mates.

[BIRD CALLS CONTINUE]

The Common Nighthawk makes noise with its wings as well as its voice. (Photo: Gavin Schaefer; CC Generic 2.0)

FITZPATRICK: In this habitat, as climate gets warmer, the whole zone moves up, and as they move up these foothills, they actually are going to disappear; so besides being threatened by outright logging, they’re now quite threatened, in addition, by climate change.

[MORE BIRD CALLS]

FITZGERALD: So in addition to soundscapes, you featured some specific species in this project as well. Let's listen to one.

A Nighthawk’s nest. (Photo: Mike Allen; CC BY-NC-SA Generic 2.0)

[SOUNDS OF INDRI LEMURS]

FITZPATRICK: These are the amazing sounds, clarinet-like toots of the Indri, the last of the great lemurs. This is a big treetop lemur with no tail. Lemurs are, of course, living in the forests of Madagascar, and limited to Madagascar. And these big black and white teddy bear-like animals are living in a family group, and as the dawn breaks and the misty forest begins to lighten up, the groups talk to one another, announce each other’s presence tree to tree with these amazing choruses of toots and hoots. This is one of the rarest of all the lemurs. It’s limited to just a few places in eastern Madagascar rainforests where they've been protected and where the habitat itself is in reasonably good shape. The Madagascar forests are severely threatened by logging through the last 150 years. Illegal logging is really causing trouble even where the forests are being preserved.

The Indri lemur is the last of the great lemurs. (Photo: David Cook; CC BY-NC Generic 2.0)

FITZGERALD: Let's hear another one. This next soundscape comes from the Congo.

[SOUND OF TROPICAL FOREST, INCLUDING AFRICAN FOREST ELEPHANTS]

FITZPATRICK: These are African forest elephants and some of the sounds you can barely hear because their frequency is so low. They're literally at the bottom end of the human hearing range, and even below that. We have a little social behavior going on here among some forest elephants. In the background of course there are frogs and insects of the wet, tropical forest night. The African elephant is in very serious trouble for poaching, for deforestation. The demand for ivory continues to escalate despite the worldwide bans on its trade.

[SOUND OF AFRICAN FOREST ELEPHANTS AND OTHER FOREST SOUNDS]

FITZPATRICK: And so the poaching stories in both the Savanna elephant species and these Forest elephant species are absolutely horrific. This Forest elephant piece is especially moving because you can literally feel the vibrations in your body. The subwoofer is actually behind the wall. If you put your hand on the wall, you can really feel that wall pulsing in and out.

African Forest Elephants are threatened by poaching and deforestation. (Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; CC BY Generic 2.0)

FITZGERALD: So, John, we talk a lot about endangered species on the show, but a lot of it is, you know, we read papers and we read books. What do you think that sound and soundscapes can bring to the conservation conversation?

FITZPATRICK: Even as we live our daily lives, we populate the world with our own sounds. Those are actually beginning to drown out the sounds of nature, and even force animals to change their behavior because of our own sounds. By emphasizing sound, we realize how important sound is across the natural world—animals below the surface of the ocean, animals at the bottom of lakes, animals in the treetops, from the huge ones to the tiny ones—they’re all communicating to each other by sound, and so the systems that are endangered out there go well beyond the physical structures of those habitats and the physical beauties and behaviors of the animals. They all have acoustic habitat as well as physical habitat.

FITZGERALD: What you hope that someone visiting the exhibit at Cornell takes away from the experience?

FITZPATRICK: Really what we love to do at the Cornell lab is encourage people to hear the sounds that are lost in the background and work with our daily lives and our individual behaviors to try to keep those sounds from disappearing.

The loon’s call can be heard at dawn and dusk in the Northern U.S. (Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; CC BY Generic 2.0)

[SOUND OF THE LOON]

CURWOOD: John Fitzpatrick directs the Ornithology Lab at Cornell and spoke with Living on Earth’s Emmett Fitzgerald.

[SOUND OF THE LOON]

Related links:

- Hear more sounds from Cornell’s Macaulay Library

- See and hear more of Maya Lin’s “What is Missing” project

- Listen to what Purdue has been doing with soundscape ecology

- Scientists at University of Puerto Rico are using computers to sort through sounds

- Bernie Krause has collected endangered sounds and designed soundscapes for over forty years. Hear our story with him here.

Branching into New Sounds

Diego bows twigs to create tonal sounds. (Photo: Diego Stocco)

CURWOOD: Now, Cornell’s Sound Ring is a 9 foot round of walnut wood – and a lot of our music depends on wood: the bodies of guitars and violins, the keys of a marimba, drumsticks and, of course, those clarinets and other woodwinds. Sound designer Diego Stocco decided to go back to the source and play a tree itself, for his project, aptly titled, “Music from a Tree.” All the sounds that you’ll hear come from an old olive tree behind his house in Burbank, California.

[BACKGROUND SOUNDS OF THE CITY]

STOCCO: We are in the backyard of my house and there is a tree. It’s a regular tree, nothing special, not one of the tree you see in the pictures, you know, that look all perfect – this one looks imperfect, but that’s probably the beauty of it. That’s why I was able to extract so many sounds. So, the beginning of this musical experiment was to create the rhythm first, and to create the rhythm I used a big branch by hitting against the cortex and leaves, so basically it’s like this:

[SHAKING BRANCHES; TAPPING SOUND ON TREE]

These two green twigs started to grow very fast after the recording of “Music from a Tree.” Diego wonders if playing music on the tree increases circulation and stimulates growth. "I don't know if it's a coincidence, but those are growing exactly from the branch I was hitting at the beginning of the video," he said. (Photo: Diego Stocco)

STOCCO: There is a sound that comes from the cortex when you pluck it.

[SOFT, HOLLOW SOUND]

STOCCO: I tuned the twigs with a pencil sharpener, so the shorter the twig, the higher is the pitch of that note. And then I added the tonal sounds. So, I have in front of me, I don’t know what, at least five different twigs. So, this is one.

[HIGH PITCH, SQUEAKY SOUND]

STOCCO: Then I have this here for the bass.

[LOWER PITCH, VIOLIN-LIKE SOUND]

STOCCO: And I have another here, which is higher in pitch. I can also play them with two bows, but what I did was trying to organize those sounds into something more meaningful. I mean more musical, I don’t know if it’s more meaningful or not, but more musical.

[TREE AND TWIGS BEING PLAYED TOGETHER]

STOCCO: So this, it doesn’t really sound as a musical piece now, but…

[MORE SYNCHRONIZED, RHYTHMIC MUSIC]

STOCCO: OK. I got it. That groove keeps going and then…

[BASS SOUNDS FROM TWIGS ADDED]

Diego uses a stethoscope-like microphone to amplify the sounds of a tree. (Photo: Diego Stocco)

STOCCO: It might be just an idea, but I was thinking it would be really fantastic to play a forest, not just by myself – imagine like 30 people in the forest selecting different trees, selecting different sounds from those trees; creating a real piece of music not just hitting branches and stuff. Definitely, you cannot bring the forest in the stadium, you know? [LAUGHS] Some people thought that I was, you know, kind of violent with the tree, but it’s not! It’s not! As an additional note, I would like to say that moving the tree is creating vibrations actually makes the circulation better, so the tree is enjoying people making music with it.

[MUSIC CONTINUES THEN STOPS]

STOCCO: And, uh, that’s the idea basically behind music from a tree.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s Ike Sriskandarajah whittled our audio portrait of Diego Stocco and his musical tree. There are pictures at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Hear more of Diego's compositions

- Watch the original music video from Music From a Tree

[MUSIC: Chet Baker “I Talk to the Trees” (The Best of Chet Baker (Remastered)]

Sounds of Winter

A beautiful winter landscape. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

CURWOOD: New England winters are usually cold and gray, but even though many people long to welcome the return of the light and the warmth – well, there are also some special pleasures of winter that it would be a shame to overlook. So, even though you might have pity on those people who live and work where it’s often frigid and miserable, there can be a silver lining to this season up in the north – if you take the time to listen. Living on Earth commentator and New Hampshire resident Sy Montgomery explains.

[CHICKADEE CHIRPING AND WINGS FLAPPING]

MONTGOMERY: At no other time of the year are sounds so sharp. The scolding winter call of the chickadee. Wind howling through oaks, or whispering through pines. The clarion call of wind chimes, piercing as the cold itself.

[XYLOPHONE-LIKE SCALE OF WIND CHIMES SOUNDING]

MONTGOMERY: Hearing may be the richest sense. Helen Keller wrote she felt its absence a handicap far worse than blindness. As if to make up for winter’s void – of colors muted, touch numbed, and scents sealed – winter’s sounds are the most vibrant.

[WHIZZ OF RUBBER SNOW TUBE SLOWING TO A STOP, CHILDREN LAUGHING]

MONTGOMERY: Sound travels further over frozen ground. Frozen surfaces are rock-hard, so they don't absorb sound – they reflect it. And when the atmosphere above is warmer than the ground, sound bounces back toward the ground. Winter’s freeze is like having a sound reflector in the sky.

[SCRAPING, RHYTHMIC GLIDE OF SKATES ON ICE]

MONTGOMERY: Winter’s bareness amplifies and clarifies its voices. Spring and summer are crowded with ambient noise: the sounds of birds and insects, the rustle of animals in the woods, the whisper of grasses and leaves – not to mention the hubbub of so many people and their machines.

[CREAK OF SWAYING TREE]

MONTGOMERY: In summer, leaves absorb sound, especially the higher frequencies. But now, the trees are bare, summertime’s murmurs are hushed, and snow is covered with hard ice crust. Sound slices through the air—stark, clear, pure.

[CRUNCH OF FOOTSTEPS IN SNOW]

MONTGOMERY: So this is the best time of year, I think, to go somewhere secluded – just to listen. Listen for the voice of the wind. The ancients said that Boreas, the north wind, loved a nymph who was changed into a pine tree. Boreas still rages and howls through oaks and maples and beech, but his voice is quite different when he speaks to his love.

The frozen land of Ice and snow has a sound all its own. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

Listen to the voices of the trees. They creak like rusty hinges as they sway in the wind. Sometimes trees will even pop loudly – it can sound like fireworks – their wood expanding and contracting during sudden changes in temperature.

Listen to the voice of the ice. On a lake, sometimes, you can hear the ice squeak, or crack, or even boom. Even safe, solid ice will make a cracking sound as it expands—scary to an ice skater—but if you’re walking in the woods, the booming of a lake is like music.

And remember, in winter, that one of the greatest rewards of listening can be silence. Orchestras know this. At the end of a performance of Mozart’s Fantasy in C Minor, a thousand ears strain for the last note.

[PIANO MUSIC RUNNING UNDER]

MONTGOMERY: Silences are different in winter, too. This is not the soft, glowing stillness of pre-spring, or the absorbing quiet of swimming underwater. No, winter’s silence, like its sounds, is piercing, clear and cleansing, like a shooting star, well worth seeking and savoring.

[PIANO MUSIC CONTINUES AND FADES AWAY]

CURWOOD: Sy Montgomery is the author of more than a dozen books including The Good, Good Pig, The Search for the Golden Moon Bear, and The Wild Out of Your Window: Exploring Nature Near At Hand.

Related links:

- Sy Montgomery

- More about Sy Montgomery

[MUSIC: Ian Ethan “Rhyme & Reason” (The Narrow Way)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jenni Doering, Lauren Hinkel, and Jennifer Marquis are all part of our team. Our show was engineered by Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth