January 16, 2015

Air Date: January 16, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Keeping Foods and the Climate Cool

View the page for this story

A third of the world’s food never gets to the table but rather spoils in transit — food that could feed more than the 870 million people on Earth who don't get enough to eat. United Technologies’ Chief Sustainability Officer John Mandyck tells host Steve Curwood that improved refrigeration and transportation of perishable foods through the “cold chain” could combat world hunger and climate change without the need to grow more food to feed an increasing population. (07:25)

Training Your Brain to Crave Healthy Foods

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

A new study involving MRI brain scans suggests that nutritious dieting can shift cravings towards healthier foods. Tufts Professor of Nutrition and Psychiatry Susan Roberts tells Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer about the findings and how food interacts with the brain. (06:35)

The Collapse of Western Civilization

View the page for this story

Science historians Naomi Oreskes of Harvard and Erik Conway of CalTech's new science fiction book, The Collapse of Western Civilization lays out how devastating our lack of action on climate change could be. Oreskes join host Steve Curwood to discuss how democracy, the free market and science are all failing humanity and the planet. (16:30)

Alaskan River Riches: Fly-fishing and Salmon Science

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s three-part series, Alaskan River Riches, looks at Southeast Alaska’s salmon economy and potential threats from mining. In the first segment, reporter Emmett FitzGerald wades through a small stream near Juneau for a lesson in casting and salmon science from a fly-fisherman with a conservation ethic. (13:56)

Crested Auklets Winter in the Bering Sea

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

In the winter months, the Bering Sea is frigid and hostile to most species, but the Crested Auklet, a petite seabird, calls it home. BirdNote’s ® Mary McCann explains how this whimsical-looking puffin cousin thrives amongst the icy waves. (02:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: John Mandyck, Susan Roberts, Naomi Oreskes

REPORTERS: Helen Palmer, Emmett FitzGerald, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. As the world tries to cut global warming emissions, there’s one huge and unexpected source of greenhouse gases few people think about.

MANDYCK: Food waste by itself represents 3.3 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide. If you measured food loss as a country on its own, it would be the third largest emitter of greenhouse gases, behind China and the United States.

CURWOOD: How keeping foods cool could help feed the hungry, and cool the planet. Also, in Alaska, wild salmon help drive the economy

HIERONYMUS: If we give these guys fresh water and good habitat to spawn in, these fish come back year after year after year, and we can keep making money on them.

CURWOOD: But locals say plans for mines upstream in Canada could threaten the fish. That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable, place to live.

[THEME]

Keeping Foods and the Climate Cool

A third of the world’s food goes to waste, and most of the losses come from spoilage on its way to being consumed. The average piece of produce in the U.S. travels 1,500 miles from its source. (Photo: Crystalline Radical; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. As much as a third of all of the food produced by farmers around the world goes to waste, most before it even gets into a kitchen. Yet millions of people don’t get enough to eat, and the carbon footprint of all that wasted food is enormous.

Much of the wastage is due to the lack of proper refrigeration, especially in the developing world. So there’s a new push to spread the system known as the "cold chain," the use of refrigerated containers, trucks and trailers to keep food cool as it travels from field to fork. The first World Cold Chain Summit in London recently aimed to spur the discussion on how to improve this network to prevent food loss. John Mandyck, the Chief Sustainability Officer of United Technologies Building & Industrial Systems, hosted the Summit and came into our studio, and we should note UTC is an underwriter of Living on Earth. Welcome back.

United Technologies executive John Mandyck gave the keynote address at the inaugural World Cold Chain Summit, held in London in November 2014. (Photo: Courtesy of United Technologies)

MANDYCK: Steve, it's great to be back.

CURWOOD: So, why do we lose so much food?

MANDYCK: Well, food loss happens in two different places, predominantly. At the consumer level, about one-third of our food is lost because we buy too much and we throw it away. That's an issue mostly in the developed markets. In the developing economy, it's a different problem. The food never makes it out of harvest. It rots on the field because there isn't a good transportation infrastructure, or if it's transported, it's transported in poor conditions to a wet market, an outdoor market, where the food rots waiting for consumers to buy it. So, it's an inefficient system in the developing economy, and that's where we're trying to raise the level of awareness and dialogue.

CURWOOD: What's the climate cost of all this food waste and loss? I mean, I imagine that all the food that never gets eaten has to have a huge carbon footprint.

The human diet has various components: grains, meat, dairy and vegetables. Unlike grains, which have a long shelf life, perishable produce such as dairy spoils easily and its longevity is contingent on the effectiveness and efficiency of the cold chain.

(Photo: Kyle Spradley/Curators of the University of Missouri; Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

MANDYCK: It's staggering, Steve. So, food waste by itself represents 3.3 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide. If you measured food loss as a country on it's own, it would be the third largest emitter of greenhouse gases behind China and the United States.

CURWOOD: So now, your meeting was about the cold chain. What kind of food is transported through the cold chain and how's its importance compared with non-perishable foods?

MANDYCK: Well, the perishable products you can think of - meat, fruits, vegetables, dairy - those are all essential elements of our diet that complement grain but have different characteristics than grain for preservation. This is exactly where the cold chain can play a role, to extend the supply of those foods which aren't making it to our tables due to food loss.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about some of the technologies that can be used going forward.

MANDYCK: Sure, so the cold chain has several different elements to it, so you can think about, "Ok, if food is grown at a farm, how do we store it at the farm before we move it?" So that would be cold rooms right at the farm. Then when we move the food to a production facility, for example, it could be in a refrigerated truck or trailer. At the production facility we have to make sure it's maintained with the proper temperature. And then, of course, when it gets to the retail setting, to a grocery store or a corner market that it's stored, maintained and presented in a refrigerated display case so that it extends the supply of that food.

CURWOOD: What are some of the improvements in technology that will make this cheaper and more efficient?

The World Cold Chain Summit was held November 20th in London. (Photo: Courtesy of United Technologies)

MANDYCK: There's been several advancements in the cold chain from an environmental standpoint to green the cold chain itself. Using solar technology to power battery packs for these products. So technology providers have a role to play, to actually scale technology to what the need is. We've done that with a product we call CitiFresh. It's a simple box refrigeration unit for a box truck, and it's meant to solve the problem of the farmer in India who's transporting tomatoes in the back of an open pick up truck 100 kilometers from this farm to the market and watching them rot en route, when instead he could be using a simple truck that cools his produce to about 40 degrees - that's it - and transport that same food to market and get better yield so he can sell more produce.

CURWOOD: Now, in places like Sub-Saharan Africa, India, the lack of electricity is profound. How does the call for improving the cold chain rely on development in these places?

The Carrier’s Citifresh refrigeration system is compatible with a wide range of box trailers and helps to maintain safe food storage temperatures. (Photo: Courtesy of United Technologies)

MANDYCK: Clearly, development is needed. A critical role governments can play is looking at the role of food safety standards. Food safety standards have the benefit of jump-starting the cold chain, but they also have the benefit of making sure our food security is in place and that people are receiving fresh produce such as meats and dairy to see that produce in top quality because it is preserved and transported and stored under proper conditions.

CURWOOD: So I’ve seen projections that by 2050, we're going to need 50 percent more food on the planet.

Food from overseas often travels on container ships. The journey between ports can be long, and so adequate container refrigeration systems are essential for maintaining the integrity of food quality. Innovations have increased the efficiency of this part of the cold chain. (Photo: Derell Licht; Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

MANDYCK: I would argue that we need no more food on the planet—that we produce enough food on the planet today to feed everybody today, and if we do it more efficiently—we feed the people tomorrow. We just need to make sure that we get the food that we make to the place that it needs to go. It's harder to imagine a more inefficient system for such an essential resource. We simply can't grow more and throw more away as we grow our planet. It's not sustainable, we don't have the land to do it, and we don't have the water to do it.

CURWOOD: Let's say someone listening to this conversation says, "This is a terrific idea. I know these folks living in Sri Lanka that could really use this." What's to be done to put money in the pockets of the people who can't buy this infrastructure?

MANDYCK: Well, one element of financing could come from the climate change debate. As we look at ways to solve climate change, there will be financing available for technologies that will mitigate climate change effects. Food waste and food loss is one of those. The low-hanging fruit for climate protection is literally rotting, and that's food waste. It's rotting before our eyes, and the climate debate is missing this fundamental and significant element for how we can address climate change together but also to address hunger, and by doing that we think we'll provide greater opportunity to prevent food waste and get more food to more people who need it.

CURWOOD: Terrific concept to connect the dots between world hunger and climate and all that. How do you get this going?

UTC’s John Mandyck spoke with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood in our Boston studio. (Photo: Ashley Barrie/United Technologies)

MANDYCK: There's this new organization that’s just forming called the Global Food Cold Chain Council which will bring together technology providers, suppliers, retailers and the food industry to think about ways we can not only green the cold chain in the first place, but to lower the carbon footprint of the cold chain, and use the cold chain as an essential element to solving this issue of food loss. Today, if you think that 870 million people aren't getting enough food—we can't feed the people on our planet today—how are you going to feed the people on our planet that are coming in the next 35 years? Projections show we're going to add another 2.5 billion more people on this planet. We don't have the capability to feed them with the inefficient systems that we have today. We know we can feed more people, and we know we can address the carbon emissions from food loss to make a meaningful difference for climate protection.

CURWOOD: John Mandyck is the Chief Sustainability Officer of United Technologies Building and Industrial Systems. John, thanks for taking the time to speak with us today.

MANDYCK: Steve, thank you very much.

Related links:

- The World Cold Chain Summit

- “Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention” study for UN Food and Agriculture Organization

- Carrier Transicold’s truck fleet provides an option for solving India’s cold chain problem.

- The World Cold Chain Summit Proceedings 2014

- Infographic on food wastage, CO2 emissions and more

Training Your Brain to Crave Healthy Foods

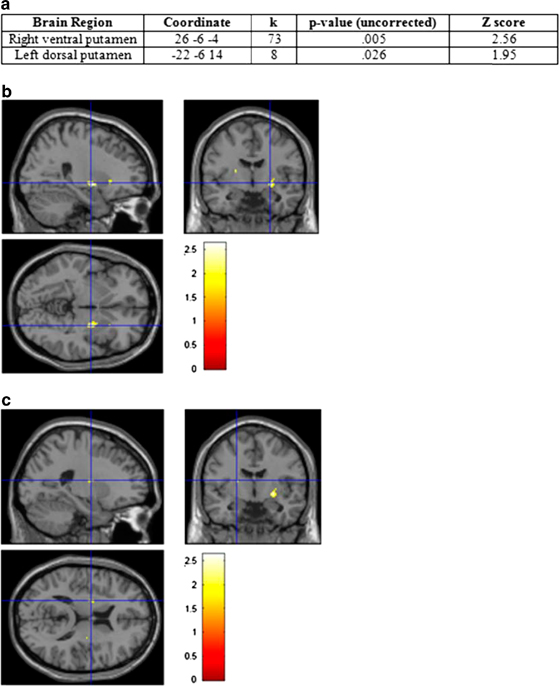

CURWOOD: Now a fair amount of food waste comes when affluent consumers buy healthy foods they should eat, but then leave them to molder in the fridge in favor of high fat and sugared junk food. Let’s face it, junk food can be addictive and hard to kick. But a recent study in the journal Nutrition & Diabetes suggests that it’s possible to retrain the brain to crave healthier options, by using a strategy called cognitive restructuring. For the study, researchers randomly assigned overweight or obese people to either a control group or a weight-loss intervention group, which met regularly and was provided a high-fiber, high-protein diet. After six months, an MRI showed the intervention group had an increased brain response to healthy protein and fiber-rich foods, and less response to high-calorie junk foods. To find out more, we called up a study co-author, Professor Susan Roberts of the Nutrition School at Tufts University. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Researchers showed participants images of ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ foods while in an MRI. The scientists then compared brain activities between the groups. (Photo: Courtesy of Susan Roberts)

PALMER: So can you give me a short description of your study and what its results were in terms of dieting?

ROBERTS: What we have is the first demonstration that it's really possible to rewire people's brains so that they learn to like healthy food and that they're less tempted by junk food. We did some baseline brain scans and then we randomized people to what we called a weighted-listed control, or to our own weight loss intervention and then six months later we remeasured them, and we were looking at changes in the brains’ addition centers to see how much they were lighting up for different kinds of foods.

PALMER: And what did you find when you look at the brain scans?

ROBERTS: So, we showed people a bunch of pictures, and some of the pictures were of healthy food. There was green salads, grilled chicken, all the things that people know are healthy. And then, there was also things like french fries, big deluxe chocolates and fried chicken, things that everybody knows it's not good to eat too much of. And we were looking for their brains’ response to these pictures. What you're doing is you're looking for the amount of neuronal activity in this rewards center. This was a study about what tempts people, and the results are really quite amazing. They really were less tempted for things like fried chicken, and more tempted for grilled chicken after they'd been through the intervention compared to our weight-listed people who got nothing.

PALMER: Now, you call this cognitive restructuring. What exactly are you doing?

The iDiet, which was developed by Dr. Susan Roberts and used in the study, includes recipes for Tanzanian Chicken Kebabs, using ingredients found in most supermarkets. (Photo: Courtesy of the iDiet)

ROBERTS: So, cognitive restructuring is the process of changing your brain. When you see a brain scan that has somebody lighting up less for junk food and lighting up more for healthy food, what you've done is you've changed the pathways in the brain. You've effectively put some of those pathways connected to junk food to sleep, and you've rewired some other pieces so the healthy pathway is more active.

PALMER: But surely that means that if you happen to pass a donut shop and say, "Oooh, I really feel like a donut or I'm really feeling hungry, I'll just have one of those,” could you backslide into the old junk food ways?

ROBERTS: You could definitely backslide. I mean, the power of this approach is that people say they're less tempted, and so they're less likely to stop for that donut. But, you know, you can regrow those craving circuits for donuts. It's not like we've killed the circuits. I think we've put them to sleep. And so, there's a certain amount of care if you'd like not to get casual and eat the things you're no longer craving just because they're around in order to maintain this new and kind of healthier way of eating.

Diets high fiber help people feel full and satisfied after a meal. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

PALMER: I'm interested if there are lots of different possible circuits or if there's one circuit and what you've done is change the one circuit.

ROBERTS: There's a ton of different circuits. There's a circuit roughly speaking for every food.

PALMER: Oh, really. So it's just of matter of which circuits light up?

ROBERS: Well, I think eating healthy food when you're hungry is one of the most important things people can do on their own. Because hunger is a very important way to kind of push those pathways in the right direction.

PALMER: So tell me a little about the intervention. What did it entail?

ROBERTS: So, first of all, a disclosure. I think this is a really advance in obesity and treatment, and as a scientist I can't possibly scale this to make this available to millions of people. So I have given the program to a company, but what it is, we have our own unique dietary composition. We have menus that we get people to follow while they learn how to do the new program. We've designed the menus so they have a ton of choices. We have pizza. We have hot dogs. We have steak. We have ice cream sundaes. And some of them come when recipes, and but of them are just instruction meals where you buy the right stuff in the supermarket and you put it together. And the brain training happens as a result of eating the right things and not eating the wrong things.

Dr. Roberts says that including high-fiber, low-glycemic index versions of familiar foods in a dieting program helps dieters lose weight. (Photo: Courtesy of the iDiet)

PALMER: So, if you're allowing people to eat pizza and eat burgers and eat hot dogs, there's got to be a very strict kind of portion control behind this as well.

ROBERTS: Well, portion control is part of it, but the composition of these foods is very different. It's a fairly high-protein diet; it's a low-glycemic index diet. It's a very high fiber diet. So they can have pizza, but it's my own formulation, which has more fiber and more protein and less carbs, for example. So that's one of the ways we get rid of the cravings is that we give people a taste they like, but the composition is about a composition for control and cravings.

Dr. Susan Roberts is a Professor of Nutrition and Psychiatry at Tufts University and creator of the iDiet. (Photo: Courtesy of Susan Roberts)

PALMER: But you're suggesting that a particularly high fiber diet, which is not necessarily what's to be found out there unless you're shopping very carefully...

ROBERTS: I think shopping carefully is definitely part of it. There's tons of good, high-fiber low-carb breads, crackers, pastas, even soups. All of the foods that you could want for a healthy weight regulation are out there today. Careful shopping is actually what it comes down to. You can't just go back to exactly what you were doing before because what you were doing before caused you to gain weight. So there's some long term changes that need to be made. But I think what we're going is getting people to enjoy those long-term changes so they don't feel that deprivation.

CURWOOD: Susan Roberts, author of The “I” Diet, and Professor of Nutrition and Psychiatry at Tufts University spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Related links:

- The original study published in Nutrition & Diabetes

- The iDiet, developed by Dr. Susan Roberts based around this research

CURWOOD: Coming up...a science historian’s words of warning about warming – and what the future might hold if we fail to heed them. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Iron & Wine "Each Coming Night" from Our Endless Numbered Days]

The Collapse of Western Civilization

Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway recently published a science-fiction book on the failure to act on climate change and its disastrous results. (Photo: Courtesy of The Collapse of Western Civilization promotional webpage)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. A slim paperback novel called “The Collapse of Western Civilization: A View from the Future” landed in our office the other day. Its cover art caught our attention: under a lowering sky, a red desert stretches to the horizon and a bottle with a message sticks out of the sand. Its authors are two science historians: Naomi Oreskes of Harvard and Erik Conway of CalTech. Their 2010 non-fiction volume “Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming” was a best seller.

CURWOOD: This latest book switches to science fiction. It’s 2393. An historian living in the Second People’s Republic of China reflects on how science, democracy and the free market all failed to keep global warming from upending society and nearly driving humans extinct. Naomi Oreskes joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

ORESKES: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So why does a historian write fiction?

ORESKES: Well, Erik and I were struggling with some way to convey something important that we felt we had come to understand: people really weren't getting why climate change really mattered, and lots of people had the impression that climate change was something that was just about polar bears. So we wanted to write something that would convey why this is not just an issue about polar bears; this is an issue about us, about our way of life, and also about our institutions—about our economic and political and democratic institutions.

CURWOOD: Talk to me a little bit about how you decided what effects of climate disruption that you included in here in your description, and how likely those are.

ORESKES: This is a work of fiction because it's imaginary because it takes place the future, but everything that happens in the book up until 2013 has actually already happened. So we didn't have to make up any of the parts the story that take place up until the present, and everything that happens beyond 2013 is based on projecting outward the scientific evidence that already exists. So we already have scientific evidence that hurricanes are possibly becoming more intense. We already have very strong scientific evidence for sea level rise and the destabilization of the West Antarctic ice sheet. We already have scientific evidence for the role of climate change: things like droughts and crop failure. So we simply took all of the scientific information, both of things that have happened already or things that are very plausibly on the horizon, and then we wove a story around imagining that those things actually happen.

CURWOOD: So what you're saying is: If you see the boulder rolling down the hill, you don't have to wait to know that it's going to wind up someplace towards the bottom.

ORESKES: Exactly. That's exactly right. And we also wanted to say that although we don't want to disparage the work that we ourselves have done, it didn't take a lot of imagination to imagine what would happen when that boulder hit the bottom, especially if there were a town sitting at the bottom of the hill.

CURWOOD: One of the key parts of your novel is the notion that democracy fails and fails miserably. Why did you pick that theme?

ORESKES: Well this really fell out from our book "Merchants of Doubt". So in "Merchants of Doubt" we told the story about a group of men who fought the scientific evidence of climate change because they were afraid of its implications, that is to say, it would lead to the undermining of democratic systems and become a kind of invitation for authoritarian governments to take control of the marketplace, of the relocation of people, and other things like that, and so we felt that the profound irony of the story was that by denying the reality, they actually increased the likelihood that disruptive climate change would lead to the very outcomes that they most dreaded.

CURWOOD: So the one civilization that comes out comparatively well in your novel is China. Of course, China, in some respects, is the oldest civilization on the planet, they've been continuously operating for the last 5,000 or so years, but why did you pick China?

ORESKES: Well, there were two reasons. The first is the one you suggested: that China is the oldest continuously existing civilization on Earth. So just from a simple logical, practical point of view, it seemed most plausible that China would continue, even if other civilizations did not. But we also wanted to bring out this ironic point that if things really start to go bad, it's going to be the authoritarian countries that are more in a position to take control of the economy and relocate people, deal with food shortages and food riots. So we wanted to bring out that point: that if you really care about democracy, you want to be doing everything your power to stop climate change because disruptive climate change will not be friendly to liberal democracies.

CURWOOD: What of what China is doing today supports your thesis here?

ORESKES: Well, China's very complicated, and lots of people like to bash China because there's this in a huge pollution problem in China and just amazing, amazing emissions increases the last ten years that very few people anticipated. So it's very easy to look at China and to blame them, and to say, why should we take action on change when their emissions growths are so rapid? But at the same time China has actually made massive investments in solar energy, in fourth-generation nuclear power. There's a lot of talk in China about a carbon tax, so China's this complicated country where both good and bad things are happening at the same time. So in the optimistic scenario, the good side of what's happening in China, the carbon tax, the mass investment in solar power—those would be the places that prevail. We don't really take a position on whether that's what happens. We simply speculate that the authoritarian aspects of Chinese culture become resurgent again and those aspects then come to the fore as China remobilizes and moves hundreds of millions of people to higher, safer ground.

CURWOOD: Part of your book is really tough on the scientific method, the drive for scientists just to be absolutely sure that something is right. Why do you talk about that?

ORESKES: Well, one of the issues that's come up a lot in the last few years surrounding the whole issue of climate change is the question of scientific communication, and a lot of scientists have thought that this was simply a problem of people not really understanding the science. And Erik Conway and I have argued that that's not really true, that a lot of the resistance to climate change has to do with the political and economic issues that are at stake. But there is one element of it that we think is about scientists and scientific communication and that's the fact that scientists hold themselves to an extremely high bar before they're willing to say that they know something is true, so, an example that many people have heard about has to do with hurricanes.

We have tremendous amounts of evidence that extreme weather events are getting more extreme, and we know that when the ocean warms up you have more energy to drive hurricanes. So there's lots of good reasons to link climate change to hurricanes, and to say that as the world warms, we expect hurricanes to become either more frequent or more intense. And yet, the scientific community has been reluctant to make that link because it hasn't hit this high level of confidence, which is the so-called 95 percent confidence limit. So by setting the standard so extremely high, scientists sort of protect themselves against a certain kind of error, the error of thinking something's true that isn't, but they put all of us at risk to a different kind of error, which is the error of doing nothing—the error of thinking we're not sure about something that's actually taking place.

CURWOOD: So what you're saying is that science doesn't much like the precautionary principle, doesn't much like the majority of evidence, wants the overwhelming amount of evidence.

ORESKES: Yeah. I guess. I mean, I don't really like to talk about the precautionary principle in terms of climate change because we're way past the point of precaution. I mean, precaution would've been doing something about this 20 years ago. I guess the way I like to think about it is there's two metaphors that lots of people are familiar with: one is crying wolf and the other is fiddling while Rome burns. Scientists have been very, very afraid of crying wolf, and the consequence of that is that we've all been fiddling while Rome burns, or maybe I should say, we've been fiddling while Greenland melts.

Naomi Oreskes is a Professor of the History of Science and Affiliated Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Harvard University. (Photo: Department of the History of Science, Harvard University)

CURWOOD: Naomi, what about the trend in science to have scientists be highly specialized?

ORESKES: Yes, the specialization of science is a really important part of this problem; it's something we talk about in the book. So climate change is a very complicated issue in which the physical, the biological, the economic and political aspects of our world all come together, but climate change as an issue has mostly been understood by scientists as a question of the physical environment, the atmosphere and to some extent the ocean and the ice sheets. And scientists are very, very specialized; so even within the physical sciences you have people who specialize just in ice, and even within ice you have people who specialize just in ice cores, or just in ice modeling or, you know, just in the bubbles inside the ice. And this highly specialized aspect of science is partly why science is powerful, but at this same time it makes it hard for scientists connect the dots. On Twitter, a bunch of us have started using the hash tag “#connectthedots” because we're trying to make the point that it's true: no one hurricane, no one storm, no one flood proves that we have climate change, but the collection of all of these things, all of the different dots is making a very, very clear picture. And one of the strangest things that Erik Conway and I feel as historians is that in a weird way, we found ourselves in this position of connecting the dots, and we found ourselves talking about things and saying things that we felt confident we're true, things we felt were supported by scientific evidence, and yet which not that many scientists were actually talking about.

CURWOOD: Economics is called the dismal science by some; and in your book economists, well, they don't come out terribly well.

ORESKES: [LAUGHS] Well, of course nobody really comes out terribly well in the book; so we're equal opportunity historians in that respect. But the principal point we try to bring attention to in the book is not so much economics as a discipline, but economics as an ideology, the ideology that we call ‘free market fundamentalism’. And this has been an important theme for Erik and I since we first started working on this issue, which is nearly 10 years ago, that many of the people who are in denial about the reality of climate change have a kind of faith that the market will somehow do its magic, and that this problem will somehow be miraculously solved by the invisible hand of the marketplace moving all the pieces into place, and coming up with some kind of solution.

We've known about the reality of climate change for a long time now, and we've been watching the effects of climate change for at least 10, 15 years now. To think that the market on its own will somehow miraculously solve this problem is in my opinion just wishful thinking, and so we're trying to bring attention to the fact that while there are many good things about market-based economies, we face a really significant problem that's not going to be solved by the free market on its own. It hasn't been solved by today and there's no evidence to suggest that it will be solved. And so thinking about that wishful thinking, that kind of magical thinking is really, really crucial to understanding how to break the logjam and figure out what we really need to do about this issue.

CURWOOD: To what extent are you saying that catastrophic climate disruption is a market failure?

ORESKES: That's exactly what we're saying, and it's not just us. I mean, many economists have said this too. So in fairness to economists, it's not as if no one in economics community recognizes this. Nick Stern, who's the former chief economist of the World Bank, has said that global warming, climate change, is the greatest market failure ever seen, and I think that's exactly right.

CURWOOD: Now, let's face it: humans very often do things that aren’t good for us on an individual level: smoke cigarettes and drink too much, knowing full and well that it’s likely to kill us ultimately. So with that in mind, what you think are some potential solutions to the way that we are hurting ourselves by, you know, keeping our heads tucked in the sand about what's happening with the climate?

ORESKES: Well what you said is true, but it's also true that humans have great capacity to change, in particular when they work together and have good leadership. So since you mention tobacco, and that's something that Erik Conway and I wrote about in our previous book, we know that in the case of tobacco more than 75 percent of Americans smoked cigarettes back the 1950’s; today that number's down to only about 25 percent. Millions of lives have been saved in America and elsewhere around the world through tobacco control.

So how did that happen? Well, it was a combination of two important things: one was people understanding the scientific evidence that tobacco smoking can kill you, and the other was leadership, leadership from people like the U.S. Surgeon General who spoke to the American people about what the risks were. So this is why telling the truth about science, being articulate about the science, fighting against disinformation about the science is so important. We, the American people, need to have good information in order to make good decisions, and we've been denied good information on climate change because there has been so much disinformation, misinformation, false equivalence, and we’ve also been lacking leadership for all kinds of reasons that I think the American people kind of get.

CURWOOD: Well, let's talk about leadership. A key point of your book is that leaders really failed to act on a timely basis. What can we do now to change the scenario that you’ve made?

ORESKES: Well, this is of course a tricky issue. I feel like I've been waiting for a lot of years for a "Nixon goes to China" moment, but it hasn't happened yet. So when leadership fails, when a top-down approach doesn't work, then you have to think about bottom-up, and I think that's why increasingly were seeing signs of activism, especially among young people. So at my university at Harvard, at MIT, at Stanford, all across the United States, students all around the country are asking university leaders to think about their investments in the fossil fuel industry and to say that maybe the time has come where that's no longer an acceptable thing to do. So they are already starting to demand at their elders either fix it or get out of the away. [LAUGHS]

Erik Conway is a Historian of Science and Technology at the California Institute of Technology. (Photo: Courtesy of The Collapse of Western Civilization promotional webpage)

CURWOOD: You're a historian. Where have we had that kind of fundamental change in human history?

ORESKES: Well, many times. I mean, if you look at the history of the United States, the Civil War and the abolition of slavery is an extremely important example because slavery was a profound and tremendous evil and we abolished it, but it took a Civil War. And I don't think anybody wants to say that the Civil War was a good thing. The abolition of slavery was a good thing, but the Civil War was a huge human, political, and social tragedy. So the way I think about it as a historian is: can we please try to find a way to fix this problem, short of having some kind of terrible outcome like the Civil War?

CURWOOD: The view of some is that you don't get radical changes in leadership and behavior without revolution.

ORESKES: Well, see I don't agree with that though. I mean, again, if we go back to tobacco, we have seen very, very significant social change over tobacco and that didn't involve a revolution, that involved people working hard systematically on a lot of different levels. So we have models for social change that involve disruption; we have models for social change that involve progress without horrible disruptions.

So I think we have a choice here, and I think in a way that's why Erik I have written this book. We want to say to our readers, there is a choice here. And the choice is in our hands, but time is running out. We can’t sit on our hands indefinitely and expect this to come out OK.

CURWOOD: Naomi Oreskes is co-author of the new novel called “The Collapse of Western Civilization” along with Erik Conway. She teaches at Harvard University. Thanks so much for taking time with us today, Professor.

ORESKES: Thank you. It's been really great speaking with you.

Related links:

- More about Oreskes’ and Conway's The Collapse of Western Civilization: A View from the Future

- Oreskes’ and Conway's previous non-fiction book, Merchants of Doubt, depicts how scientists can distort scientific facts to advance a political and economic agenda.

[MUSIC: Alberto Mesirca "Farewell to Stromness (arr. T. Walker)" from Alberto Mesirca: British Guitar Music]

CURWOOD: Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line anytime at 800-218-9988, or write to PO Box 990007, Boston, MA 02199. Our email address is Comments@loe.org, and visit our webpage at loe.org.

CURWOOD: Coming up...heading north to Alaska in search of fish. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Devin Townsend Project "Infinite Ocean" from Ghost]

Alaskan River Riches: Fly-fishing and Salmon Science

Mark Hieronymus fishes in a stream just outside of Juneau. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Summer in Southeast Alaska is salmon season. As the days grow long, the iconic fish begin to run up rivers and streams, and the fishing economy jumps to life. Juneau isn’t the biggest fishing town in the region, but salmon are everywhere: on every restaurant menu, on t-shirts in gift shops, and in the harbor hundreds fishing boats constantly come and go. Just a few miles outside of the city small commercial fishing boats cruise around the mouth of the great Taku River, netting the salmon as they head upstream. Juneau is also a popular jumping-off point for fly-fishing trips, and sport fishing is an important source of income. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald spent some time in Juneau in the summer of 2014, reporting on the fish, their importance to the people who live there, and potential threats to the salmon that drive the local economy. And a fly-fisherman with a conservation ethic gave Emmett a lesson in casting and salmon science.

FITZGERALD: It’s a blue summer day, about as warm as it gets in Southeast Alaska. Fly-fishing guide Mark Hieronymus has the morning off, but he’s more than happy to spend it at one of his favorite fishing holes—although he’s not about to let me give away the precise spot on national radio.

HIERONYMUS: You could say that we’re at a small stream very close to the mouth of Taku River in Taku inlet.

[SOUND OF TRAMPING ALONG BANKS]

FITZGERALD: In chest high waders, we tramp along the pebbled banks. Where the stream narrows, Mark wades in and we slosh across to the other side.

[SOUND OF SLOSHING WATER]

FITZGERALD: The rushing water squeezes the waders tight and cold against my legs, and I have to lean into the current to avoid toppling over.

[SOUND OF SLOSHING WATER CONTINUES]

FITZGERALD: On the other shore Mark sets up shop. He puts his pole together, ties on a feathery orange fly, and starts showing me how it’s done.

HIERONYMUS: You’re going to go like this with this rod, you’re gonna cast it back out there and you want to cast this kind of gentle, so I’ll show you this cast called a roll cast.

FITZGERALD: K.

HIERONYMUS: If it ever tightens up that’s a fish.

FITZGERALD: There’s so many fish in this stream that even I manage to get a few bites, but Mark’s the real master here. As the line dances back and forth above his head, he tells me about the different salmon in Southeast Alaska.

HIERONYMUS: The largest of those in terms of numbers are pink salmon. The run sizes fluctuate but this year, to give you an idea, this is going to be a poor run of pink salmon this year and they’re projecting a harvest of around 22 million with a total escapement of somewhere over 30 million.

FITZGERALD: There’s five salmon species in all. As well as the pink there’s Chum, Coho, Sockeye…

Hiking in, fishing pole in hand. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

HIERONYMUS: And then we get King Salmon too, that run in here. Those are the commercially caught fish and then we have also steelhead, which is the anadromous form, the ocean going form, of rainbow trout. That’s sort of the prized sportfish, that’s the crown jewel of most sport catches and here in Southeast Alaska we have officially about 330 streams with steelhead in them. But if you talk to folks that have fished for them for a long time they’ll tell you that that number is closer to 450 streams of steelhead in ‘em.

FITZGERALD: This one?

HIERONYMUS: This one does have Steelhead but you don’t have to print that.

FITZGERALD: Mark lands his fly a few feet from the opposite bank, just above a cluster of dark shadows hanging in the water. They look like rocks to me, but Mark says they’re pink salmon, or as he calls them, humpies after the characteristic hump on back of the male. These humpies are in their final days of life, waiting for more salmon to join them upstream. When they get a quorum, they’ll spawn and die.

HIERONYMUS: These humpies have a two-year life cycle. So these fish here when they spawn, they’ll die and they enrich the stream here. And the young swim out to sea next year, next spring. Those fish will return in 2016 in the same numbers, sometimes even more.

FITZGERALD: It doesn’t take long for Mark’s fly to get some action.

HIERONYMUS: Well, this is a pink salmon. Looks like a female, and it’s a little one -- grabbed it.

[SOUNDS OF FLOPPING AND SPLASHING]

FITZGERALD: There you go.

HIERONYMUS: Yeah. It’s got a little nip on the outside of him there. There’s seals that sit out off of this, the river mouth here and the seals’ll try to grab the fish.

FITZGERALD: Wow, look at that thing. So you think that wound there is a seal?

HIERONYMUS: Yeah that’s most likely a seal; it’s pretty fresh.

FITZGERALD: Is that going to be life-threatening to that fish?

HIERONYMUS: Well, the thing about it is this fish is on its spawning run, so its days are numbered right now, and so that wound might get infected, but that’s not going to be the cause of it dying. The cause of it dying is going to be—it’s on its spawning run; it was gonna die anyway.

A tributary in the Taku River Valley, a major salmon river that flows into the sea outside of Juneau. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

FITZGERALD: The salmon life cycle is a well-documented natural wonder. Somehow, each fish manages to find its way back from the open ocean to a little stream like this one, where it was born. Scientists think they use the earth’s magnetic field and their sense of smell to help them get back home, but it’s still a bit of a mystery.

This summer, though, the salmon cycle was disrupted on one of the biggest sockeye rivers in North America. On August 12th, a dam holding back waste water from the Mt. Polley copper and gold mine in British Columbia burst, sending over 6 billion gallons of polluted water and mine waste into the Fraser River, just as the sockeye had begun to swim upstream. Mark says that as he watched the horrific images on the news, all he could think about was the salmon.

HIERONYMUS: Once they enter fresh water on their spawning run, their time is limited. And so they have to find clean gravel and have clean water to spawn in. That’s the whole reason these fish come back. So if there’s no place for them to do it or if the habitat is compromised, then the results are, potentially, you’re missing an entire year class of fish.

FITZGERALD: Canadian officials say the Fraser River Sockeye have weathered that spill fairly well, but it’s way too early to know what the long-term impact on the population will be. The wastewater was filled with heavy metals that could linger in the rivers and lakes for years to come, and that’s bad news for the salmon.

HIERONYMUS: What people don’t think about is the effects of some of these harmful toxins to phytoplankton or in-stream invertebrates. And if you lose that food base, then you’re going to lose the fish. It’s not an “if.” If there’s nothing there for them to live on, then you lose the fish. You’re basically ripping out the bottom of the food chain and the fish follow.

FITZGERALD: Mark hopes that the Mount Polley disaster is a wake-up call about the dangers of mining in sensitive watersheds. British Columbia is in the middle of a mining boom, and several BC mines are planned along rivers that flow right into Southeast Alaska—rivers like the Unuk, the Stikine, and the Taku, near where we are right now. Mark says if anyone doesn’t understand why these projects are a bad idea, just look at Mount Polley.

HIERONYMUS: The potential for something like that to happen, as we’ve seen, has now gone up greatly, because it has happened. And so to have it happen in a place that produces, place like, say, the Taku valley, or the Stikine valley, or the Unuk valley, that produces a substantial amount of Southeast Alaska’s fish, frankly it’s fairly horrifying.

FITZGERALD: As he talks, Mark is constantly casting, his arm rocking back and forth with a practiced finesse. He lays the line down on the water and lets the fly drift through the salmon shadows. If they don’t bite in five seconds, he yanks it out and starts again. For Mark, protecting fish is a personal economic issue. He’s had a lot of different jobs since moving to Juneau 25 years ago—seafood processor, fly designer, and today, as well as being a fly-fishing guide, he’s the Sportfish Outreach Coordinator for Trout Unlimited Alaska.

Mark is a fly-fishing guide based in Juneau. He takes tourists out on day-trips to streams like this one. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

HIERONYMUS: People, when they find out I work for Trout Unlimited, they say, is that some kind of environmentalist organization? I say, no, we’re conservationists, there’s a big difference. I want to conserve it, so I can keep killing it and keep making money off of it. But they have to be around for me to do that.

FITZGERALD: Before long, Mark’s got another fish on the line.

[SOUNDS OF SPLASHING WATER]

FITZGERALD: He pulls the salmon out of the water. It’s another female, he says.

HIERONYMUS: The thing that people don’t really realize is that, if we give these guys fresh water – clean water – and a good habitat to spawn in, the management is such that these fish come back year after year after year and we can keep making money on them.

FITZGERALD: Mark pulls the hook out of the lip and slides the fish back in the water. It lingers for a moment then swims off. In only a few weeks, he says, she’ll lay her eggs and die. But if the water stays clean and the habitat healthy, he’ll be back on this bank in two years, trying to catch her children.

For Living on Earth, this is Emmett FitzGerald in Juneau, Alaska.

CURWOOD: Emmett FitzGerald is back now from Alaska and joins me in the studio. So Emmett, this sounds like quite the trip.

FITZGERALD: Yeah, Southeast Alaska is really a pretty remarkable place. It feels cliché to talk about how wild Alaska is, but really that's what it felt like to me coming from Boston—it's just this epic landscape, and you're right in the middle of it. You know, I was struck, I flew into Juneau and the first thing I realized pretty quickly is that there's no roads coming in and out of Juneau – it's the capital city of the biggest state in the union – there's no roads coming in and out it. But there's a ferry system, a public ferry system that connects all the different towns in Southeast Alaska, so when I left Juneau I took a ferry. I left at like 4 o’clock in the afternoon, and took a ferry overnight to this little town called Wrangle, far in the south of southeast Alaska. And I took the public ferryboat, and you're on this boat and you feel like you're on a cruise ship. You should have paid a luxury tour price to see the views that you're seeing, but you're really just traveling like everybody else. I expected there to be tourists on the boat, and there were some tourists, but it was mostly just everyday Alaskans going to see their family or they had business down south. And I was particularly struck, there was a high school sports on mine that was traveling to wherever their next game was.

CURWOOD: All the while you're going past this amazing scenery, these huge trees...

FITZGERALD: Yes, it’s the inside passage is this archipelago of islands, and I saw all kinds of wildlife. Right as the sun began to set, humpback whales started breaching all around the boat and it was pretty spectacular.

CURWOOD: How did you feel about the eagles that you'd see?

FITZGERALD: Yeah, for me, the first time I saw an eagle I pushed the guy next to me and said, “Oh my God, look it’s a Bald Eagle!” And the guy looked at me like, “Dude, whatever, it's a Bald Eagle. They’re everywhere.” And yeah, they’re like pigeons in Juneau; I must have seen thousands of Bald Eagles before I left.

CURWOOD: Now, tell us a bit about the mine that the fisherman in your story is so concerned about. I've heard about the Pebble Mine in Alaska, but these are different, right?

FITZGERALD: Yeah, I mean, Pebble is obviously a story that's got international attention over the last few years. That's this massive copper and gold mine in Bristol Bay, which is one of the biggest Sockeye producing fisheries in the world. And that project is kind of in limbo at this point. A lot of the major investors have pulled out, and now that EPA is involved it's in the court process. But as that has dragged on, some of these mining companies that aren't getting as much attention in British Columbia have really started to move forward. They're also still in a preliminary stage and some of them have big financial and regulatory hurdles to clear, but people in southeast Alaska – which is also a really important salmon fishery – are beginning to look at these mines and say, “Wait a second.” Because a lot of them are on riversheds that flow over the border from British Columbia into Southeast Alaska, and a lot of those fishermen depend on those riversheds.

King Salmon gather together to spawn. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

CURWOOD: And, I gather when I heard in your piece about the Mount Polley disaster, that that's got people really concerned.

FITZGERALD: Yeah, the Mount Polley thing is really something that really highlighted the danger there for a lot of people. This video – you should take a look at it, we're going to have a link to it on our website – but the video is so startling—this torrent of gushing sludge from the Mount Polley mine pouring down this scenic river valley. And I think a lot of people saw that and were just really pretty terrified that something with some of these new mines could happen. It's obviously not, you don't know that just because a mine is built doesn't mean something disastrous like that is going to happen, but it definitely is a worst-case scenario and a lot of people are scared.

CURWOOD: So this week you took us fishing. Where are you going to take us next week, Emmett?

FITZGERALD: Yeah, so next week we're going to look at this mine which is near the Taku River, which is just outside of Juneau and a major salmon river, and it's called the Tulsequah Chief. The original Tulsequah Chief was abandoned over 50 years ago. It's a copper and gold mine, and there's still actually some pollution from that mine that's leaking into the river. But now, a new company is trying to redevelop the project. So what I'm going to do, I took a plane ride in this tiny little float plane and they're like, propeller planes and they're everywhere in Alaska because there's no roads. And so I went up there with a fisherwoman from Juneau and you get to hear her reaction when she sees this mine site and this potential mine perched right on the river that's so important to her business.

CURWOOD: I'm looking forward to it, Emmett. Thanks a lot.

FITZGERALD: Thank you.

Related links:

- Read more about fly-fisherman and conservationist Mark Hieronymus

- Watch a video of the Mount Polley spill

Crested Auklets Winter in the Bering Sea

Orange-scented oils produced by the Crested Auklet help to protect and condition the small seabird’s feathers while repelling parasites, such as ticks. (Photo: Ryan P. O’Donnell)

BIRDNOTE® CRESTED AUKLETS

[MUX - BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: Well, we stay up in the far north for BirdNote® this week and head out to sea with Mary McCann.

[SOUNDS OF WIND AND WAVES]

MCCANN: The Bering Sea in winter is a realm to which most people – aside from some very hardy fishermen – give a wide berth. Winter in this northern sea framed by Alaska and Siberia is frigid, stormy, and dark. But remarkably, some birds seem right at home here.

The Crested Auklet is one such bird.

[WIND AND WAVES. CALLS FROM A FLOCK OF CRESTED AUKLETS]

MCCANN: A petite cousin of puffins, the Crested Auklet stands 10 inches high, weighs nine ounces, and is feathered in charcoal gray. This little seabird takes its name from a comical crest curling out over the top of its large, orange bill. If that’s not whimsical enough, Crested Auklets bark like Chihuahuas.

The Crested Auklet calls Bering Sea islands home. (Photo: Paul Jones)

[CRESTED AUKLETS BARKING]

MCCANN: And to top that off, the seabirds exude an odor of oranges from a chemical they produce that repels bothersome ticks.

MCCANN: Crested Auklets nest in immense colonies on Bering Sea islands, and remain nearby through winter. Picture a flock of tens of thousands of Crested Auklets flying low across the wave tops, yipping like an army of Chihuahuas... while trailing a perfume of fresh citrus.

[CRESTED AUKLETS BARKING]

MCCANN: I’m Mary McCann.

A feathery tuft curls out and over the Crested Auklet’s short orange beak. (Photo: Paul Jones)

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Calls of Crested Auklets [132013] recorded by S. Seneviratne.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2014 Tune In to Nature.org December 2014 Narrator: Mary McCann

CURWOOD: There are pictures of these quirky looking birds at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Hear more about Crested Auklets on BirdNote’s site

- Read about Crested Auklets’ lifecycle

- Crested Auklets and their relatives

[MUSIC: Steve Reich "Music for 18 Musicians: II. Section I" from Music for 18 Musicians]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, Alaska has tough regulations on how and when people can fish, so has one of the healthiest salmon fisheries in the world.

ERIKSON: Alaska is the jewel of the world when it comes to fisheries management. This state is second to none.

CURWOOD: But new mines planned over the border in Canada have fisherman fearing for the future. That's next time on Living on Earth.

[HUMPBACK CALLS]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week up in South East Alaska in the company of Humpback Whales.

[HUMPBACK CALLS]

CURWOOD: These Humpbacks were recorded under water, where they’re keeping company with a harbor Porpoise.

[PORPOISE AND HUMPBACK CALLS]

CURWOOD: Bernie Krause, who recorded these marine mammals, also caught the sound of a glacier calving off an iceberg.

[GLACIER COLLAPSING INTO THE SEA]

CURWOOD: This Adventure in Sound is part of the Wild Sanctuary series, on a CD called Whales, Wolves and Eagles of Glacier Bay.

[MORE SOUNDS FROM ALASKAN WILDERNESS AND WATER]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett FitzGerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, Lauren Hinkel, James Curwood and Jennifer Marquis are all part of our team. Our show was engineered by Noel Flatt. Special thanks this week to Trout Unlimited. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth