July 3, 2015

Air Date: July 3, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Newly Discovered Algae Helps Corals In Warming Oceans

View the page for this story

Coral reefs are a delicate ecosystem. Their health largely relies on the symbiotic relationship between algae and corals, which typically breaks down in warmer water. But as Jörg Wiedenmann, Professor and Head of University of Southampton’s Coral Reef Laboratory, tells host Steve Curwood, a new species of algae is allowing corals in the Persian Gulf to withstand rising ocean temperatures. (06:35)

Pond Scum May Be Associated With ALS and Alzheimer's

View the page for this story

Blue-green algae are actually a type of bacteria that proliferates due to excess nutrients in streams and lakes. It can be toxic to humans and animals and as University of Montreal biologist Zophia Taranu (Taran-YOO) tells host Steve Curwood, these poisonous bacteria are blooming more frequently in waters around the world as the world warms. (06:50)

Louisiana's Moon Shot

View the page for this story

The state of Louisiana is disappearing at the fastest rate in the world, and its sinking deltas threaten some of the nation's crucial oil, gas and fisheries industries. But Louisiana has a “Hail Mary” plan to save it. ProPublica reporter Bob Marshall speaks with host Steve Curwood about the state's ambitious and first-of-its-kind plan to preserve the region and what it might cost if they fail. (11:20)

Climate Change & Pacific Northwest Glaciers

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

Glaciers set the Pacific Northwest apart and are essential for the region’s drinking water, hydropower and salmon survival. But as EarthFix’s Ashley Ahearn reports, disappearing glaciers make the Northwest uniquely vulnerable to the effects of climate change. (06:10)

Meltdown in Tibet

View the page for this story

The glaciers of the Tibetan plateau feed into rivers that provide water to much of the Asian continent. But now in an effort to generate power for its massive population, China has begun damming those rivers. Writer Michael Buckley talks about his book about the assault on Tibet’s natural resources with host Steve Curwood. (09:00)

Harvesting "Himalayan Viagra"

View the page for this story

A Tibetan fungus is being sold on the Chinese medicine market as an aphrodisiac, bringing new income and problems to rural villages on the Tibetan plateau. Anthropologist Geoff Childs tells host Steve Curwood that he’s found one village that is managing the resource sustainably. (06:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: STEVE CURWOOD

GUESTS: Jorg Wiedenmann, Zophia Taranu, Bob Marshall, Michael Buckley, Geoff Childs

REPORTER: Ashley Ahearn

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The discovery of a new species of algae in the Persian Gulf might offer a way to help coral reefs stressed by rising sea temperatures and pollution.

WIEDENMANN: Coral reefs are by no way doomed, so corals try to fight back and they try to adjust to the changing environment and they have a higher capacity to do so then we had previously thought, but this will not be enough.

CURWOOD: Also, melt water from glaciers is the key to hydropower in the Pacific Northwest.

RIEDEL: Having glaciers provides stability to our water supply. So, you get into the mid-late July and the snow is melted out of the mountains, if it weren’t for glaciers, our stream flow would drop pretty dramatically.

CURWOOD: But now the glaciers are melting. We’ll have that and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

Newly Discovered Algae Helps Corals In Warming Oceans

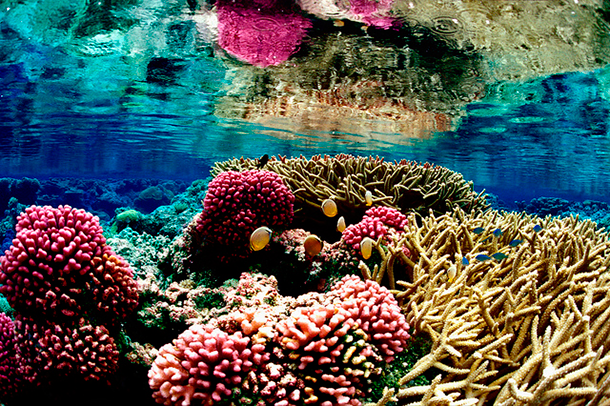

Researchers have discovered a new species of algae that can survive higher ocean temperatures. Corals depend on the symbiotic relationship to survive. In turn, this enables the coral host to withstand warmer waters as well. (Photo: USFWS Pacific; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Today we have some good news, as well as some bad and definitely ugly, and it all has to do with algae—sort of. So let’s start with the good, and it’s good news for coral reefs, which are in trouble in many spots around the world. Overfishing and pollution aren’t helping, but the big challenge seems to be shifting water temperatures, which can drive out the algae that reefs depend on for food from photosynthesis, leaving the reefs unhealthy or dead and bleached a ghostly white. Now science has discovered a species of algae in the Persian Gulf that doesn’t seem to mind high or low ocean temperatures. Jorg Wiedenmann of the University of Southampton was part of the team that made the discovery.

CURWOOD: Jorg, welcome to Living on Earth.

WIEDENMANN: Hi there, it's a pleasure to be here.

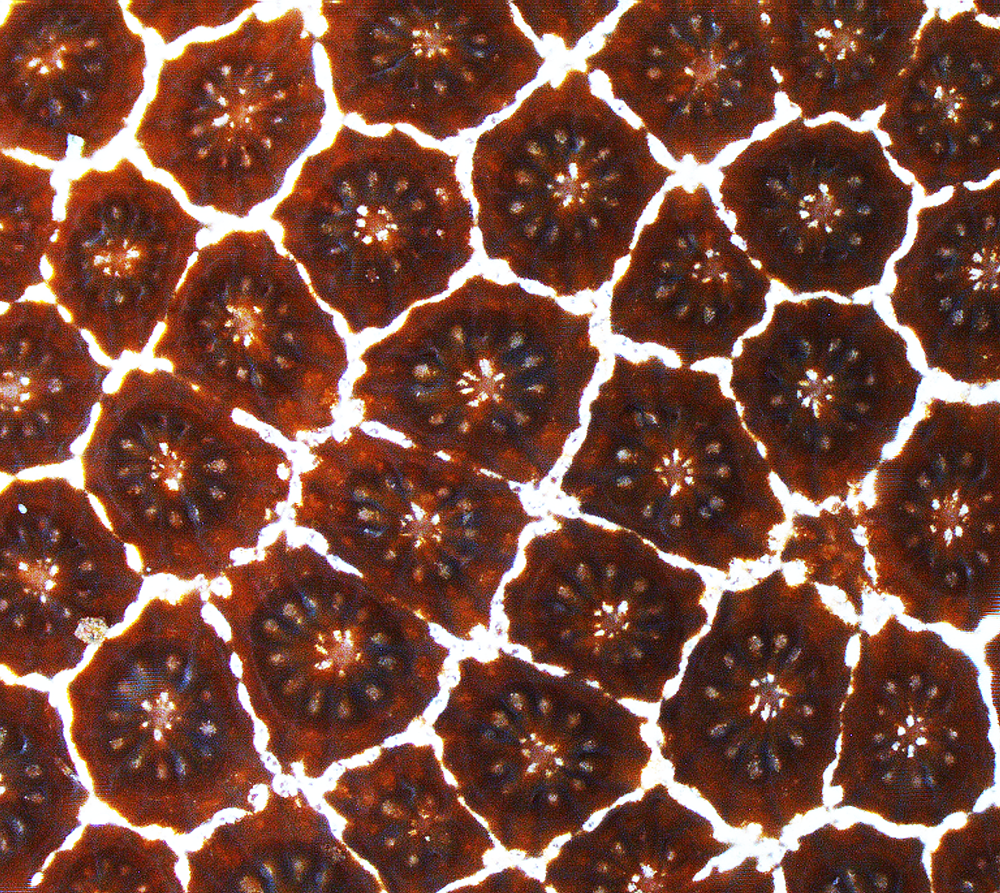

Some types of algae live symbiotically inside a coral host, photosynthesizing to feed the coral sugars and receiving shelter and nutrients in return. (Photo: Jörg Wiedenmann, J. Burt, C. D’Angelo)

CURWOOD: So, first of all, why study corals in the Persian Gulf? What's unique about that region?

WIEDENMANN: The Persian Gulf is actually a wonderful natural laboratory because they are experiencing temperatures, which are predicted for other parts of the world for the next century. So, if we want to get a better idea of what will be going on in other oceans, the Persian Gulf might be telling us already the future since the corals are experiencing heat already there.

CURWOOD: Now, why is it that warmer than average ocean temperatures typically are a problem for corals as a result of bleaching.

WIEDENMANN: So corals live together in a symbiotic relationship with this unicellular algae and they depend on their algal symbiont because they provide them with valuable nutrients and food. However, this symbiotic relationships is very honorable and if temperatures exceed a certain threshold the algae for the photosynthesis is not working properly anymore and they produce some toxic compounds which results in a breakdown of symbiotic relationship and the algae are lost from the coral. So, as a consequence the white skeleton of the animal close to the coral is shining through the tissue and that gives these corals the bleached appearance and that is actually a signal that they are severely stressed, that they have lost their symbiotic partner and as a consequence they might actually die if they do not manage to recover in this environment.

Coral bleaching results when the coral host loses its algal symbiont. Most species of algae living symbiotically inside corals can’t survive warmer waters; without algae, corals starve. (Photo: Scientific Editor; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: But you found this particular alga that can survive warm temperatures, at least greater temperature fluctuations than species known to be outside the gulf. How is this alga able to do that?

WIEDENMANN: At the moment we don't know yet how they manage to do it. The only thing that we know now and this is very exciting, that this is very new type of algae and obviously this algae is doing something very different from the algae in other parts of the world, and our future research will hopefully help find out what mechanism is by which they manage to survive these extreme temperatures.

CURWOOD: What's a potential for this particular species of algae to live symbiotically with other coral species in other places, maybe places that are under stress because of warming ocean temperatures?

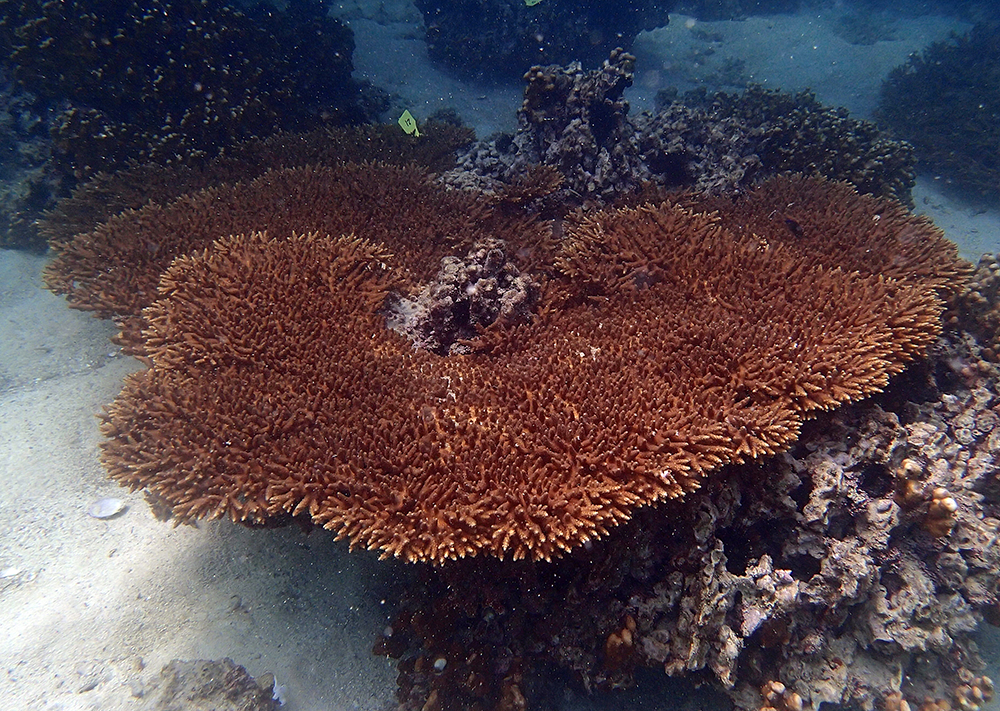

The algae living symbiotically inside corals give their hosts a brown color, seen here in a coral of the Porites genus in an Abu Dhabi reef. (Photo: Jörg Wiedenmann, J. Burt, C. D’Angelo)

WIEDENMANN: Well, so the exciting finding about that is that corals obviously have more means to adjust to high temperatures than we previously thought. In the past it was just one strain of algae, which was made mostly responsible for thermal tolerance in corals and now we certainly know that there are even different species, which could do that. So that means that the diversity of algae out there that could actually help corals to survive in extreme temperatures might be much bigger than we had previously thought. And when temperatures are rising in other parts of the ocean these algae actually might take over and help the corals to become more temperature tolerant. However, while this gives hope that corals will adjust to the increasing temperatures of the future, one also needs to be realistic about that and if we look at the Persian Gulf so we find there are about 68 coral species that can endure in these high-temperature environments. If you look in a more normal tropical environment in the Indo-Pacific, the hotspot of coral diversity, you would find about 600 species. So obviously, there are limitations to the adaptation potential of corals to these extreme temperatures. It does not mean that rising ocean temperatures are nothing bad for corals because they cannot acclimate to a certain extent.

Researchers found the heat-tolerant algae species in the Persian Gulf, where ocean temperatures can reach 96 degrees Fahrenheit. (Photo: Jörg Wiedenmann, J. Burt, C. D’Angelo)

CURWOOD: In your work what other stressors do you see besides heat that threaten coral reefs?

WIEDENMANN: Water quality plays a crucial role for coral survival and our recent work has shown that for example, nutrient enrichment of waters, which corals receive can actually lower the temperature tolerance. The temperature threshold at which corals can start to bleach and start to suffer is actually lowered. So this is something very important because that also gives possibilities to really actively promote coral reefs to become more resilient towards temperature increases. If we managed to get the water quality right in coral reefs then they are actually are more resilient towards temperature stress.

CURWOOD: So, Jorg, what's the message here? What's the message that this new finding sends us about the future of coral reefs?

Jörg Wiedenmann is a professor of biological oceanography and head of the coral reef laboratory at the University of Southampton. (Photo: courtesy of Jörg Wiedenmann)

WIEDENMANN: So, what we can see is that coral reefs are by no way doomed, so corals try to fight back and they try to adjust to the changing environment and they have a higher capacity to do so then we had previously thought, but the important message is that this will not be enough. We need to support coral reef ecosystems in their struggle to adjust to higher temperatures and reduce the pollution of the waters, reduce overfishing and to keep them in natural and good health.

CURWOOD: Jorg Wiedenmann is a Professor of Biological Oceanography and head of the Coral Reef Laboratory at the University of Southampton. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

WIEDENMANN: Thank you very much for talking. It was great fun.

Related links:

- The paper in the journal Nature

- “Newly Discovered Algae Could Save World’s Coral From Climate Change”

- About Jörg Wiedenmann

- The Coral Reef Laboratory at the University of Southampton

Pond Scum May Be Associated With ALS and Alzheimer's

Blue green algae, or more accurately, cyanobacteria (Photo: Lake Improvement Association; Flickr CC 2.0)

CURWOOD: And now – algae’s bad and ugly side -- pond scum. It isn’t just a summer nuisance.

International research led from Canada suggests that blue green algal blooms are growing more widespread around the world and could threaten our health. Indeed, last August authorities in Toledo Ohio banned residents from drinking their water due to excess levels of a toxin produced by algae in Lake Erie. And some scientists are suggesting an association of the increase in blue green algae with diseases ranging from liver tumors to Alzheimer’s and other neurological disorders. Zophia Taranu is a biologist at the University of Montreal and the lead author of a paper in Ecology Letters.

TARANU: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: So, first off, what is blue-green algae?

TARANU: So, blue-green algae is actually a bacteria that produces a blue-green pigment. More recently, we called them cyanobacteria.

CURWOOD: Huh. So why did we think that they were algae?

TARANU: Because they have a lot of the similar characteristics as algae or phytoplankton, but what differs is that they don't have membrane bound organelles that would make them algae.

CURWOOD: So, you looked at this bacteria to see how it's doing around the world. Tell me about your study?

TARANU: So the motivation behind our study was that there has recently been an increased attention in the media and also people living around lakes that there was possibly an increased occurrence of these blue-green algae or cyanobacteria in lakes. But we didn't know whether or not it was a true increase or if people were just paying more attention, and there's also the suggestion that we, with global warming and changes to the land use that we are creating these opportune conditions for an increase in cyanobacteria. As so our study was really motivated to try and quantify whether or not cyanobacteria are increasing over time.

Cyanobacteria blooms like this one are on the rise around the world (Photo: Jukk_a; Flickr CC 2.0)

CURWOOD: And what did you find?

TARANU: So we found that over the past 200 years cyanobacteria have been increasing significantly, and that the increase was accentuated or accelerated since particularly the 1960s and this coincided with that changes in modern agricultures, so the application of fertilizers and also coincided with increases in the global temperature.

CURWOOD: Now, what you suppose is causing this global rise all around the world in blue-green algae or actually it's bacteria.

TARANU: So what we found in our study and has being shown at local scales as well is that the increase in fertilizer coming from the land into lakes is driving this increase so, cyanobacteria do really well when the concentration of phosphorus and nitrogen, these nutrients that we are applying on the land are high and they can outcompete phytoplankton during those conditions.

CURWOOD: Yes, I'm thinking the summer of 2014 Toledo, Ohio had to stop drinking water from Lake Erie because of a bloom like this. What happened there?

TARANU: That particular bay has a lot of agriculture land nearby so there is more of a loading of nutrients that happens. And typically cyanobacteria forms these blooms or these scums on the surface water, and what happened in Lake Erie in 2014 was that there were strong winds that recirculated the blooms towards the bottom waters which is where that filtration plants take their water supplies and so basically there was these toxic blooms that make their way into the water supply.

Biologist Zophia Taranu testing lake water. (Photo: Victoria Shaw)

CURWOOD: So what are some impacts of cyanobacteria on our health?

TARANU: Some of them not all cyanobacteria produce toxins, but when they do bloom there is a higher occurrence of toxins being produced, and so in some cases, for example, there's been instances where livestock and pets that consume lake water that had blooms that were toxic died as a result. Typically humans don't consume lake water that has blooms in them because it has a bad taste and odor problem, so there's no known report of deaths of humans, but there is still that toxic effect. When you have direct contact, you can have skin irritations or gastrointestinal discomforts, from swimming in the water and being in contact with the blooms. More long-term effects could potentially be related to the fact that the most common cyanobacteria produce these liver toxins so it can have liver tumors that produce over a longer-term scale, but this is still speculative. There have also been studies that have correlated whether or not residents who live close to a lake and the occurrence of certain neurodegenerative diseases. This latter link is still really controversial in the literature, and something that I think we need to look into more closely into future years. The truth is we don't actually know if that link is present or not.

CURWOOD: What kind of neurological disorders are suspect?

TARANU: So some studies have linked it to ALS for example, and they found that residents that live closer to lakes, there is a correlation or higher occurrence of ALS, but because it's a correlation, it doesn't imply causation, so there could be other factors, for example, living nearby agriculture fields that have fertilizer applications or being in a large city with other environmental issues that could be a play. So even though it's a correlation we don't actually know if it's a cause.

CURWOOD: So, ALS, what other disorders?

TARANU: There was one study, for example, in Guam, around 2003 that found a certain population that consumed bats that themselves consumed the trees that had a symbiotic relationship that produced cyanobacteria. And within these patients they found symptoms that they said were descriptive of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's, so the symptoms were comparable and in the cerebral tissues of the patient had died of these neurodegenerative diseases they found what they call a bioamplification of the cyanobacteria protein. But to the best of my knowledge that's the only known case of this amplification.

Cyanobacteria is a common pond scum. (Photo: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, CC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So what are the steps you think we need to take to reduce the amount of the cyanobacteria in our waterways?

TARANU: The two dominant factors that we found in our study: the most important one was the loading of nutrients from agricultural land or the concentration of nutrients in lakes. There's also climate warming. I think climate warming is a bit of a harder issue to tackle, and people are trying to work on this continuously. The overuse of fertilizers in the agricultural land is probably something that will be more easily tackled in future years because we're currently applying... in about 70 percent of croplands across the world we're applying phosphorous in excess of need and so the quota and the mitigation needs to be applied at that end as we saw that as the primary driver of cyanobacteria.

CURWOOD: Zophia Taranu is a Biologist at the University of Montréal. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Zophia.

TARANU: Thank you very much for having me.

Related link:

More about Zophia Taranu’s study

[MUSIC: Steve Winwood and Traffic--Low Spark of the High-Heeled Boys, The Swimming Hour]

CURWOOD: Coming up –Losing ground in Louisiana – and losing ice in the Pacific Northwest. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Coleman Hawkins; “Uptown Lullaby” from The Art of Jazz Saxophone: The Masters (Laserlight 1997)]

Louisiana's Moon Shot

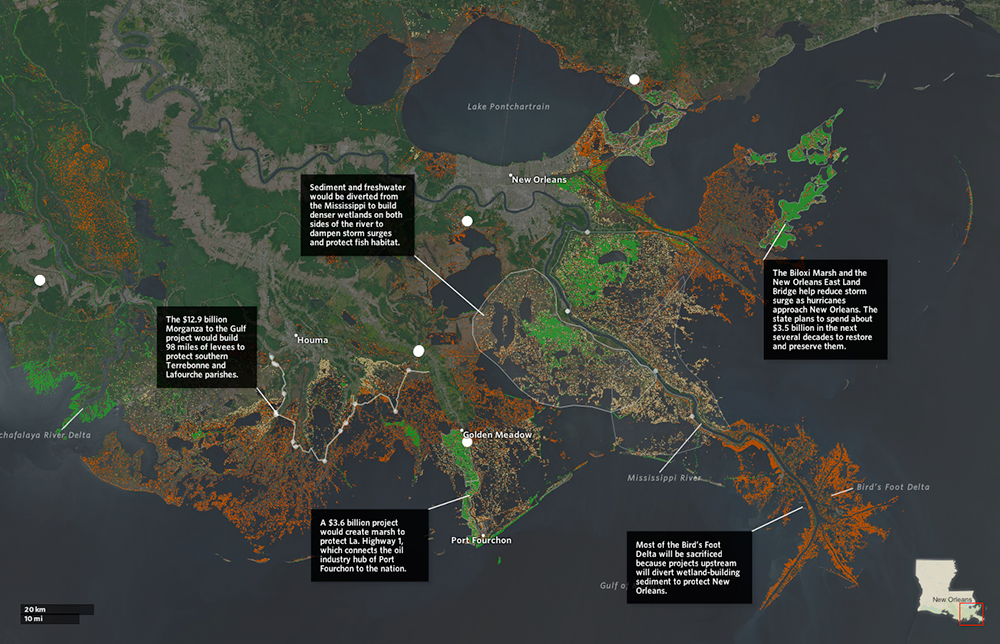

Louisiana’s Master Plan for the Coast includes projects like marsh creation, sediment diversion, levee, structural and shoreline protection, hydrologic restoration, and oyster reef restoration. The plan is ambitious and, if implemented on time, can restore and save some crucial wetland areas (in yellow and green), but some regions are sinking too quickly and will be sacrificed (in red). (Photo: Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, NASA/USGS)

CURWOOD: It's an encore edition of Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Louisiana is in trouble. The Mississippi River Delta is disappearing into the Gulf of Mexico at the rate of 16 square miles a year, some of the fastest land loss on the planet. These bayou lands are crucial to the nation's fisheries as well as regional oil and gas supplies and ironically, activity by the energy industry is helping to destroy its own infrastructure. As a response, industry and government have created an unprecedented plan to save and rebuild these wetlands over the next 50 years at an estimated cost of some 50 billion dollars. In a joint project with ProPublica, Bob Marshall, a reporter for the Lens, has co-authored an analysis of the plan called “Losing Ground”: Louisiana’s Moon Shot.

MARSHALL: What they're trying to do here has never been done before. They're trying to rebuild some of the wetlands that have been lost and then to maintain that against all these unknown variables such as subsidence and sea level rise and lack of funding. So in a very sense it is as ambitious in those two areas as going to the moon for the first time.

CURWOOD: So how do you rebuild wetlands? What are the methods that the engineering crowd is saying are possible to use?

MARSHALL: Well, the area was built by the river and that's the only chance to rebuild it is to get that settlement out of the river back into the sinking basins in this part of the state surrounding New Orleans. The problem is that there's only about half the sentiment of the river that it had when it built this area because of all the dams north of us. And the other problem is that the land is sinking at such a rapid rate, many of these areas are already too deep and too large to be rebuilt.

Lake Hermitage’s Marsh Creation project in September. (Photo: Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority)

CURWOOD: What are some of the specific projects associated with this plan?

MARSHALL: Well, marsh creation is the states term for what I call slurry pipelines. They dredge sediment out of the river; pump it into some of the sinking basins and just re-create these areas as a once were. Going forward they hope to do this in areas of 33,000 acres, and the diversions basically re-creating or mimicking the way the river built these deltas originally is the heart of this project because they can build land as long as the river is running, so that's why they're key. They're also doing lots of shoreline stabilization and they're rebuilding oyster reefs to help protect the shorelines from wave action. There are also different types of projects with levies. Half of this $50 billion is going to be spent on structural protection for hurricane storm surge and the cost of that has risen dramatically because the core of engineers discovered during Katrina that its design parameters for building levees didn't work, so they had to increase them and that's the cost up. They're also doing research on how different plants will be impacted - you have to have the plants to hold the soils together - what will happen to the fish and the wildlife and there are lots of variables and other concerns that they have to take into consideration such as leaving enough water in the river for shipping, not displacing communities that might be flooded by these projects and trying to tend to the concerns of fisherman and the oil gas industry.

CURWOOD: Now, what kind of time does it take to do these things?

Photos of Bay Denesse from 2004 and 2014. State and Federal governments noticed that the wetlands surrounding New Orleans were not accumulating sediment because of the fast flowing waters. In 2006, they cut into the riverbanks in order to slow waterflow and eventually sediment deposited, building 98 berms. (Photo: USGS, Digital Globe)

MARSHALL: Well, this plan is a $50 billion, 50-year plan. According to the computer projections, if everything works according to plan and is implemented on time they could actually be gaining more land then they're losing in aggregate by 2060. The problem is, they only have $50 billion. This has never been done before. In several other projections out there are big concerns such as sea level rise.

CURWOOD: So where are these projects taking place? Where exactly?

MARSHALL: New Orleans is about 90 miles from the mouth of the Mississippi River and most of these projects will be taking place in the stretch of river about 50 to 60 miles from New Orleans. The last 30 or 40 miles of the river delta is just being given up because it's sinking at such a fast rate, in some places five feet a century so there's no hope of really saving those areas, so they're trying to rebuild these wetlands that are close enough to the city and its suburbs and the smaller communities out there to provide some type of storm surge buffer as well as have a functional fishery. This is the most productive coastal fishery outside of Alaska in North America and it's based on these wetlands.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about some of the challenges that the planners and engineers expect in this project?

MARSHALL: Say locating the sediment diversion per se, first they have to find out how much settlement and the right types of sand and sediment that are going to be in the river at a certain location. And then of course can they get it to a basin that isn't already and deep and too wide to be treated. Then they have to figure out if it's in a stretch on the river or if they take water out of the river it won't cause shoaling to the south and disrupt shipping.

Louisiana’s Barataria Barrier Island Complex Project: Pelican Island and Pass La Mer to Chaland Pass Restoration (Photo: Coastal Wetlands Planning, Protection and Restoration Act; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, Bob, who's going to pay for this?

MARSHALL: So far the state hasn't got much help from the federal government except in the form of rebuilding the levees that they didn't build properly around New Orleans, and it collapsed during Katrina. Congress back in 2007 authorized about 27 projects that are part of this master plan, but they haven't funded any of them, and of course they haven't shown any willingness. They're waiting to see how much money the state can gain from the Deepwater Horizon settlements from BP. The state recently said they could maybe realize as much as $4 or $5 billion. If they don't find other revenue sources they figure they'll probably run up against a financial wall in about 10 years. So right now they really don't know. They're hoping that Congress will look at this and say, you know, this is an investment worth making because it pays for itself and its economic benefits to the country.

CURWOOD: And what about the oil and gas companies that make a lot of money with the infrastructure that's there? To what extent are they investing in protecting, well, their own infrastructure?

MARSHALL: Well, they will tell you they pay in excise taxes both to the federal government and to the state government. Those haven't been raised in some time, and the state will be getting a larger share of the offshore royalties that go exclusively to the federal government and get a larger slice beginning in 2017 to the tune of about $175 million a year depending on gas prices, of course, that fluctuates wildly, but the oil and gas companies have contributed things like PR campaigns and some individual projects, but as far as tapping into that financial resource to help pay for this, the state's political body, they want the oil and gas companies to willingly come to the conclusion that it's in their self-interest.

CURWOOD: Some would criticize this effort by saying, wait; we spend a lot of money to protect private profits with public dough.

Congress approved 27 projects in Louisiana’s Master Plan, including marsh creation around Highway 1, which is important for the oil industry, and sediment and freshwater diversions from the Mississippi to rebuild wetlands, protecting New Orleans from storm surge. (Photo: Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, NASA/USGS)

MARSHALL: It is a problem for the state. Other the states look here and say why should we help you if you won't help yourselves? The state's congressional delegation is also among the most aggressive in opposing climate legislation, carbon legislation, of course, this is one of the most endangered, in fact, NOAA says it's the most endangered large coastal landscape sea level rise in the country. So other states the same way to manage you know you're like someone with long cancer who wants us to help pay for the chemo but doesn't want to quit smoking. But down the road if this isn't the number one issue for the politicians in the state, I think they'll be a tremendous crisis here. There will be a storm eventually that will flood a bunch of these communities, knock out refineries. They'll expose or break lots of these pipelines and then the nation will have to deal with that. That's pretty much historically the way the country deals with these same things. We kind of move forward by crisis rather than doing proactive things.

CURWOOD: Now, the fishing industry is also big in this region so what's their role in evaluating and modifying the master restoration project plans?

MARSHALL: Well, the wetlands here, the marsh, that is really the engine that drives fish reproduction here, but, of course, you need to rebuild what you are losing because once that base of habitat gets so small, production will fall off a cliff. Problem is that the people who make money from fishing here - shrimp, finfish, crabs, oysters - have been making their fortunes on a system that has been gradually turning more saline, saltier, so the people who some of the fisherman, they don't like the idea of these big diversions being open because it will turn the water in their bays much fresher and it will displace many of their target species and so they say, "I may have to go a lot further to catch fish or oysters or crabs or there might not be any." So they're looking for ways maybe of finding funding to mitigate the economic cost to some of these people if, in fact, they would be really hurt. No one's really sure if they would be that severely impacted.

Bob Marshall is a reporter for The Lens. (Photo: Courtesy of The Lens)

CURWOOD: So, do the math for me as a projected cost of $50 billion. We know that these things end up costing a lot more the end of the day, but what is the potential loss if this does not succeed or does not even start?

MARSHALL: Well, that's hard to say, I think. You know, 50 percent of nation's refining capacities along this coast, 30 percent of its total energy supply comes in pipelines from these 4,000 rigs offshore. They would have to start looking for ways to either relay these pipelines, move the refineries, and so as this turns to open water, they have to go somewhere. They have to be rebuilt or reengineered at enormous expense, so it's quite the crisis that's fast approaching. People always ask me are you optimistic this will get done? I'm optimistic it could be done, but I think the human element is much more...and the political element is much more of a variable that could kill the effort than overcoming the science and engineering part of it. But if they don't succeed here then about a million people have to find new places to live and one of the nations key energy corridors could be disrupted, if not shut down, and the port that serves 31 states would be in serious trouble. So, you know the old cliché failure is not an option, and the other thing here is that there's a deadline. If they don't get this done and 50 to 60 years they can't get it done and it will just be this massive environmental evacuation, immigration from this part of the state north finding homes for people and industries.

CURWOOD: Bob Marshall is a reporter for The Lens. Thank you so much.

MARSHALL: Thank you.

Related links:

- ProPublica The Lens’ Losing Ground Part II: “Louisiana’s Moon Shot” includes interactives of current projects and possible outcomes

- Louisiana’s Comprehensive Master Plan for a Sustainable Coast

- Our previous interview with Bob Marshall regarding Louisiana’s disappearing coasts

- ProPublica The Lens’ Losing Ground Part I

[MUSIC: Marcus Roberts Trio & Wynton Marsalis, "New Orleans Blues" from Together Again: Live in Concert (J-Master Records 2013)

Climate Change & Pacific Northwest Glaciers

Erin Lowery is a fisheries biologist for Seattle City Light. His job is to figure out where salmon are spawning on the Skagit River and then make sure his employers’ dams release the right amount of water to allow the eggs to incubate safely. (Photo: Ryan Hasert/ EarthFix)

CURWOOD: Well, we stick with a watery theme – the frozen water this time, of the glaciers of Washington State. The Evergreen State has more glaciers than any other, except Alaska. These ice fields are breathtaking to look at, exciting to climb, and a vital part of the water supply in the Pacific Northwest. But these days they’re melting away. From the public media collaborative EarthFix, Ashley Ahearn has our story.

Jon Riedel, standing just below the Easton Glacier of Mount Baker. He has been monitoring glaciers for the National Park Service for more than 30 years. He's documented the rate at which glaciers in the North Cascades have been shrinking in recent years. (Photo: Ryan Hasert/ EarthFix)

AHEARN: Guess how many glaciers feed into the Skagit River? Just take a guess. Answer: 376. No joke.

[FOOTSTEPS IN NATURE]

AHEARN: Jon Riedel is hiking up to one of them, on the slope of Mount Baker in Washington’s North Cascades.

RIEDEL: We’re headed up along Rocky and Sulfur creeks and then we’re going to turn and follow Rocky creek up toward the terminus of Easton Glacier.

AHEARN: Riedel’s been studying glaciers with the National Park Service for more than 30 years. The sheer number of glaciers in this region sets us apart from the rest of the country, but it also makes us uniquely vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Glaciers are key contributors to drinking water supplies, hydropower generation and salmon survival in the Northwest.

Riedel pauses just shy of 4,000 feet elevation in the middle of a field of boulders. No glacier in sight.

RIEDEL: If you were here in 1907 you’d be looking right at the terminus of the glacier.

AHEARN (on tape): And now where is it?

RIEDEL: Now it’s around the corner. You can’t see it. The terminus is closer to 4,400 feet and probably at least a kilometer horizontal distance.

AHEARN: Photographs from the 1800s show this whole valley covered in ice. But that’s changing. Glaciers in the North Cascades have shrunk by 50 percent since 1900. Riedel says throughout history, glaciers have advanced and retreated over these mountains hundreds of times. But now it’s different.

RIEDEL: The glaciers now seem to have melted back up to positions they haven’t been in for 4,000 years or more so we’ve kind of gone beyond that natural scale of variability.

AHEARN: Glaciers provide billions of gallons of water to rivers in the Northwest. But it’s not just about the supply - that water arrives when demand is high.

RIEDEL: Having glaciers provides stability to our water supply. So, you get into the mid-late July and the snow is melted out of the mountains, if it weren’t for glaciers, our stream flow would drop pretty dramatically. So the glaciers are providing this meltwater at a time of year when we get no rain, when the snow’s gone, in other words, when we need it the most.

[BOAT ENGINE]

AHEARN: Perhaps no one understands that better than the people in charge of operating dams for hydropower.

RAYMOND: My name is Crystal Raymond and we are at the base of Ross Hydroelectric projects.

AHEARN: Ross dam towers 450 feet above us as we motor up Diablo Lake in Washington’s North Cascades. Raymond works for Seattle City Light. The utility operates three dams on the Skagit River that provide about a quarter of the power for the city of Seattle.

RAYMOND: So we are unique. There are not too many dams that operate in a place where some of the runoff for the project is coming from glaciers.

AHEARN: At the hottest, driest times of year, glaciers are the biggest source of water for some of the streams that feed this hydropower facility. It’s Raymond’s job to figure out what to do when the glaciers are gone. She says Seattle City Light will need to change how it stores water above the dams, maybe expanding the reservoirs to capture more rainwater and save it for those late summer months. Helping customers cut back on energy use is also going to be key. By the time millennials are retiring, summer hydropower production in the Northwest is expected to be down by roughly 15 percent. But Raymond is an optimist.

RAYMOND: It isn’t hopeless. There’s certainly a lot of uncertainty, but we know enough now to start getting prepared and with time we’ll know more, but the sooner we start the more likely we are to reduce the impacts. And there’s no time like the present.

[WATER SPLASHING]

AHEARN: Several miles downriver from Ross Dam, Erin Lowery scans the clear water for salmon nests or redds, as they’re called.

LOWERY: Right there you can see the dark shape, right there in the water. So it’s sort of near the edge of the redd. So that’s a Chinook salmon sitting on the redd.

AHEARN: Lowery is a fish biologist for Seattle City Light. The utility is required to manage its dams to protect spawning fish. Too much water released from the dams and the redds will get washed away. Too little, and they’ll be left high and dry. This mama Chinook’s tail is ragged and white where she’s used it to shovel away the gravelly riverbed to make room to lay her eggs. Now she’s guarding them.

LOWERY: She’ll sit on that redd and defend it until she loses energy and dies.

AHEARN: And Erin Lowery will do his best to defend her.

[CALLING OUT MEASUREMENTS]

AHEARN: He and his team record the location of the redd and how deep the water is there. Lowery says, glaciers aren’t just important because of the water they provide in the summer. It’s the temperature. Glacial melt flows into warming rivers like dropping an ice cube in a glass of lemonade. No glaciers means warmer rivers, and that’s bad news for salmon.

Erin Lowery is a fisheries biologist for Seattle City Light. His job is to figure out where salmon are spawning on the Skagit River and then make sure his employers’ dams release the right amount of water to allow the eggs to incubate safely. (Photo: Ryan Hasert/ EarthFix)

LOWERY: We start to affect, not only the fish themselves, but it can have a negative effect on their eggs, but in rivers that are dominated or have a glacial component to them, we see reduction in temperature, which is key to cold water fish like salmon.

AHEARN: Lowery says it hasn’t come down to a choice between fish or power yet. But he loses sleep thinking about that possibility some day.

LOWERY: I think as we move forward, I mean, it’s going to be a hard look at how we manage flows in the river with a changing climate, with a reduction in glaciers and snowpack because people are moving to the Puget Sound constantly and they’re all going to need electricity.

AHEARN: Scientists aren’t sure exactly when the glaciers will disappear. It could be within a few decades. It could be by the end of the century. But when they’re gone, they’ll be missed.

I’m Ashley Ahearn on the Skagit River.

[MUSIC: Cut Copy “Voices In The Quartz” from In Ghost Colors (Modular 2007)]

CURWOOD: Ashley reports for the public media collaborative, Earthfix. There are videos of glaciers, salmon and dams at our website, LOE.org.

Related link:

EarthFix's "What Climate Change Means For A Land Of Glaciers"

CURWOOD: Coming up: a trip to the Roof of the World, source of fresh water for more than a billion people. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Duke Ellington “Caravan” from Jazz Moods: Hot – Duke Ellington (Columbia 1937//2004)]

Meltdown in Tibet

China’s construction of dams on the Lancang (or Upper Mekong) threatens a complex ecosystem downstream that supports over 60 million people in Southeast Asia. Five megadams have already been built, eight are underway, and several more are being planned upstream in Tibet and Qinghai. In October 2012, International Rivers went to investigate the current status of dam building on the Lancang River. The 990MW Wunonlong Dam would displace several largely Tibetan villages. Two tunnels have been built to house power stations inside the mountain. (Photo: International Rivers; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Only the Arctic and the Antarctic have more ice than the glacial highlands of the Tibetan Plateau, earning it the nickname ‘the third pole’. The headwaters of some of the world's most powerful rivers -- the Yangtze, the Yellow, the Brahmaputra, the Irrawaddy, the Ganges, the Mekong - flow from the high altitude plateau into Asia, providing life-giving water for drinking, agriculture, fisheries -- and recently, hydropower. That’s the subject of a book from travel writer Michael Buckley, called “Meltdown in Tibet”, which focuses on China’s exploitation of the natural resources of the Tibetan plateau, especially water.

He joins us from Singapore.

BUCKLEY: Pleased to join you.

CURWOOD: So, you started off as a travel writer. How did you get into political polemics?

BUCKLEY: Well, it really started with a rafting trip. I was on the Drigung River, just out of Lhasa, and I'd never been on a river that powerful in my life. I was told this is just a pimple in terms of Tibetan rivers; this is nothing. But they're also talking about, the biggest problem with the kayaking and the rafting is dams, you know, because they can't get around them, get stopped by them, and I said, "Dams? Which dams?" And they said, "Well, they're all over the place." And I said, "Wait. I wrote a guidebook. I should know about this stuff. Can you tell me more?" So I starting listening to what they were saying, and they said, "Well, if you think about it, it's quite logical. There’re about 10 major rivers that come off the Tibetan Plateau that originate within China. The rivers are the most powerful in world. You've got the hugest hydro-potential ever because you’re starting in the Himalayas and dropping 3,000 or 4,000 meters." So then I started delving into it. That's where the thing got off the ground really.

CURWOOD: When did China begin building dams on these rivers?

Melting glaciers on the Tibetan Plateau feed into many of the regions’ rivers, which China is damming for hydropower. (Photo: ventdroit; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

BUCKLEY: Well, China's been gung-ho on dams ever since Mao Zedong came into power, but it was never on the Tibetan Plateau. It was always in the east, but the dam movement in China is expanding with no end in sight. See, they're really big on this green energy thing, and they're saying, "Well, you know, coal is bad;" they're expanding the use of that too. But they're looking upon hydropower as being clean. And so what they're doing, they want to double the amount of hydropower by 2020, and the way to do that is they're looking at the rivers of Tibet because the rivers of China are thoroughly dammed; you can't dam them anymore. China has more dams than the rest of the world put together, so they’re gradually working their way towards the Tibetan Plateau because they build dams in cascades. So they start off on the lower ground and as they build upwards; they use the power from other dams to complete the cascade because you need power to build more power.

CURWOOD: Overall, what would you say is the impact of all these dams on the rivers?

BUCKLEY: It's minimal for now, but it's going to get much, much worse because they've got some big dams coming up. We're not taking about small dams; we're talking about megadams, which are defined as over 15 meters in wall height for a certain size reservoir. These things, what they do...they stop the migration of fish. They stop the movement of fish, and they also stop the movement of silts. The silt carries rich nutrients to the countries downstream, and if you don't have those nutrients you’ve got to resort to fertilizers.

CURWOOD: So where is all the power going? What are the benefits to the Tibetans from all this?

A nomadic tent atop the Tibetan Plateau. (Photo: Nathan Bishop; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BUCKLEY: The Tibetans? These dams are not built for Tibetans at all. I mean, you've got a very low Tibetan population; it's always been low. And they're not involved in industry and everything; they're involved in agriculture or herding so they don't need power. They have their own source of power. For thousands of years they've used yak dung. That's all they need. You know, they stack up the yak dung, that's what they use for heating, that's what they use for cooking, that's what they use for everything because there is very little wood on the high plateau. The dams are not for them. The dams are for the Chinese, for their industry, for the military. It's very big for mining. They need dams to power mining, and mining has taken off on a very large scale now.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the mining projects that are going on there and the environmental impact of them.

BUCKLEY: Yeah basically this has picked up a lot. It used to be a small operations like gold miners, individuals, small groups, nothing major, and then along came the railway, which is from basically Xining to Lhasa. So what's happening now is that you're getting very large scale mining going on and Tibet has huge reserves of copper, lithium, gold, silver, you name it. It's got a lot of stuff that's never been touched because the Tibetans never mined anything. It's against their religious practices to dig up anything. They didn't like disturbing the ground.

CURWOOD: I gather that there've been a lot of land grabs for mining projects in Tibet.

BUCKLEY: Yes, and this is a practice that's not only in Tibet; it's across China. In the case of Tibet, they've taken over land in the grasslands especially, which traditionally is being grazed by the Tibetan nomads, and they've just ripped up any contracts that they've got with these people and told them, "Your 30 year lease is not worth anything now. Move along. Just go and get settled in the house over there."

In order to make the land grabs much more easy, they've declared these areas national parks, and this is the worst form of greenwashing you will ever come across. They declare a place to be a nature reserve and they go and inform the nomads, "You're in a nature reserve. You'll have to leave." And they say, "We've been here for thousands of years, hundreds of years." And they say, "Well, that doesn't matter."

China’s exploitation of Tibet’s natural resources is increasingly forcing the displacement of Tibetan nomads. (Photo: gill_penney; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

And as soon as they move out, they wait a little bit and along comes a mining company suddenly on the grasslands. The thing Tibetans really object is when they start mining at sacred mountain sites - a lot of villages have their own sacred mountains - and if you disturb the spirits, it's very bad karma for them. They really do not like mining at sacred grounds and mountains and there's a fair bit of that that goes on.

CURWOOD: Now what's the status of wildlife there in Tibet?

BUCKLEY: Unfortunately a lot of the wildlife has gone missing. There was a delegation from about 1980 from the Government-in-Exile, and they were shocked at the conditions the people were living under, but also, they were also shocked by the silence of the grasslands. They did not hear the herd of animals that they would normally hear: you know, the wild asses, the wild yaks, the thundering hooves, and even the birds were missing, and they started looking around. And they could not find any wildlife, and it was gone. It was just decimated. And we put this down to the military, the settlers—the Chinese settlers coming in. They would eat the wildlife for meat or export it back to China - it was considered a delicacy - but back in the 1930s the Tibetan Plateau was considered to be the Africa of Asia, you know, like the Savannas. It was lots and lots of wildlife up there, but it's all gone missing.

CURWOOD: How are the yaks doing?

BUCKLEY: Well, the yaks are doing poorly. You've got two kinds of yaks. You've got the wild yaks and then you've got the domestic ones. The wild yaks are almost double the size of a regular, domestic yak, but there's probably fewer than a thousand left in Tibet. Thousands of years ago, the wild yaks were domesticated—they were tamed by Tibetan nomads to become the beast of burden for the plateau. They get everything from the yaks. So their objective is to milk them, get the butter, cheese, whereas the Chinese attitude is a little bit different. They came up with this idea that they should make these yaks into meat where we can actually eat them.

It’s very alien to Tibetans, this idea; they don't like this idea at all. When the nomads are settled, in order to make it a non-reversible process, the Chinese will take away the yaks and send them to the slaughterhouse. If they don't have yaks, they can't survive. What you need to do with these nomads if you’re going to settle them is you have to retrain them because otherwise they have no skills. Their skill is survival on the grasslands. They know how to do that very well; they've done it for centuries. But as soon as they settle into these houses, suddenly they have to pay for water. They have to pay for electricity. They don't have a food source. So they become nobodies, like refugees in their own land.

Michael Buckley is the author of Meltdown in Tibet. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael Buckley)

CURWOOD: Michael, where do you see all this heading? I mean, what chance do Tibetans have at slowing down the damming of the rivers, the mining of their mountains, the displacement of their nomads?

BUCKLEY: Well, they're up against a military industrial complex that whatever they try to protest, it would just be squashed; people are imprisoned. People disappear. I mean, there have been a number of demonstrations against mining where Tibetans have been killed. The only chance that you might have for stopping some of this damming, which happened in the southeast, in Yunnan, Szechuan, is Chinese groups. They don't like those dams either, and they have mounted fierce protests in Szechuan and Yunnan, and they've had some successes. So I think the only chance of really stopping activity like this, lies with Chinese NGOs and Chinese groups for being very brave and manage to highlight the issues and manage to stop a few projects.

CURWOOD: Michael Buckley's new book is called “Meltdown in Tibet: China’s Reckless Destruction of Ecosystems of the Highlands of Tibet to the Deltas of Asia." Thank you so much.

BUCKLEY: OK. Well, good talking to you and thanks very much.

Related link:

Meltdown in Tibet by Michael Buckley

Harvesting "Himalayan Viagra"

Cleaning harvested yartsa gunbu prior to sale. (Photo: Courtesy of Geoff Childs)

CURWOOD: Among the many resources of Tibet is a fungus that Chinese medicine prizes as an aphrodisiac. It’s been the target of collectors and speculators, and the source of conflicts and even some deaths up in the fragile Himalayan grasslands. But one community in the highlands of Nepal has found a way to manage the harvest sustainably using cultural traditions, laws and consensus. Geoff Childs is an anthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis, who wrote in the journal Himalaya about the fungus – called yartsa gunbu.

Anthropologist Geoff Childs with Lama Gyatso (Photo: Courtesy of Geoff Childs)

CHILDS: Yartsa Gunbu in Tibetan means “summer grass winter worm”. It's actually a caterpillar of the ghost moth, which becomes infected by a fungus, and in the springtime, the fungus shoots a stoma out of the ground, which allows people to locate it in highland pastures. Generally it grows at 12,000 feet and above, and it's become very popular in Chinese herbal medicine for health, longevity, to boost the immune system. It's considered to be a libido enhancement, which is why some people like to call it the Himalayan Viagra.

CURWOOD: I gather it sells very well.

CHILDS: It's extremely popular in China now to the point where in many rural areas on the Tibetan Plateau, gathering it has become the primary source of income for rural dwellers, so people are basically suspending all other activities in the months of picking which generally come starting in late May and run through June. And the whole family moves up to the high pastures to gather it, so that it can be sold to middlemen who take it to China and that's where the market really takes off.

CURWOOD: So in general how has it been harvested in recent years?

CHILDS: People will basically crawl along the ground looking for it and when they find it they'll carefully dig it out with the spade or some digging implement and remove it from the soil because you want it intact: You want the caterpillar body and the fungal stoma as well. That's where it's got the value. If it's broken apart it doesn't have the same value so they dig it out very carefully and, you know, a good day somebody can maybe find 20 to 30 of these. Some people are adept and can find 100 or more.

CURWOOD: Wow. And each one of these is worth quite a bit.

Yartsa gunbu (Ophiocordyceps sinensis), also known as Himalayan Viagra. (Photo: Courtesy of Geoff Childs)

CHILDS: Yeah. Each one has gotten from middlemen about 500 rupees. If it's really good, maybe 750 rupees. So $5 to $7.50, which, in a place where there is very little income earning opportunities, that's a lot of money.

CURWOOD: What are the environmental impacts of all this harvesting? I mean, all these people running around the hillsides there in the mountainous Himalayas, some of that's pretty fragile stuff.

CHILDS: Yes, that's certainly going to have an impact, and especially in those areas were they allow a lot of people to gather. Number one, you're going to have people chopping down the juniper for fuelwood because they have to cook their food and keep warm, so there's going to be an environmental impact there. There is also a lot more people digging up the turf, which is fragile high-altitude alpine turf, so that we'll certainly have an impact.

CURWOOD: Now, you did much of your research in this small Tibetan area called Nubri and you say that they are doing things differently there. How so?

Rudimentary shelters inhabited by yartsa gunbu collectors. (Photo: Courtesy of Geoff Childs)

CHILDS: Yes, correct. Nubri is a valley in Gurkha district in the country of Nepal. The residents are ethnically Tibetan. They've been living there for about 700 or 800 years, so it's an indigenous population of Nepal. What they have done in contrast to other areas is they've limited the number of collectors to only residents of the villages, and so that keeps the number of collectors way down.

CURWOOD: Tell me how the community of Nubri got its regulations put in place.

CHILDS: What they've arrived at in Nubri is a combination of what they call “yultim” which we could translate as village regulations, secular regulations, and “chutim” which are religious regulations. On the religious side, there's a long tradition of protecting the landscape through these ceiling decrees. It's called a “shukya”. What they will do is, they will decree certain areas off-limits to human exploitation, and usually that's a sacred grove of trees, a certain slope of a mountain that a deity inhabits or something like that.

In terms of the village regulations the first one that I just mentioned is the exclusion of all outsiders. The second one is they've got a designated starting date, and they arrive at that by looking at the snow melt, looking at the conditions in the alpine pasture and figuring out what's going to be the likely time when it's best to gather it. And so for a couple weeks prior to the official starting date, every adult in the village has to check in four times daily to the village meetinghouse to prove that you're not collecting early. A third thing that they do is they tax it. For the first member of your household, the tax is very low; it's 100 rupees or approximately $1 dollar. For every additional household member, it's 4,500 rupees, so about $50 dollars, and they gather that tax and use it for communal purposes.

CURWOOD: So, how has Yartsa Gunbu harvest changed the economics of Nubri?

Mt. Manaslu (26,759ft.) in Nubri is the 8th highest mountain in the world. (Photo: Courtesy of Geoff Childs)

CHILDS: It's changed it tremendously. There's positives, and there's negatives. The positives are people suddenly have money that they can use for their children's education; a lot of people are using it to send their children to boarding schools. They can improve their housing. I've seen a lot of improvements in local housing, upgrading the conditions of their housing. They can buy food with it. They don't produce enough food locally; they’ve had to trade various products in the past to get enough food. Now they've got cash to purchase food. On the negative side, you can imagine that people who have never had this type of income, when they suddenly come into money, it can cause a lot of social problems, so gambling and drinking are way up. There's also friction within families. Younger members tend to take the income and go to the city and blow it all really quickly, whereas the older members want to conserve it and use it in a way that benefits the family. So it has certainly improved their livelihood and their standard of living, but of course it does come at a cost.

CURWOOD: So Jeff, looking at this from a broader resource management perspective, what are some lessons that we can take away from what's happening in Nubri?

Prayers inscribed on stones mark the trail to the high pastures where people collect yartsa gunbu. (Photo: Courtesy of Geoff Childs)

CHILDS: Trust indigenous people. Don't immediately assume that as outsiders with more education we can come in and devise a system that will work for them. I think, first of all, study what's in place. Study with an open mind and move from there.

CURWOOD: Jeff Childs is an Anthropology Professor at Washington University in St. Louis. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today Professor.

CHILDS: Thank you for talking with me. It's been a pleasure, Steve.

Related links:

- Child’s paper on sustainable harvesting and management of Yartsa Gunbu

- “Himalayan Viagra fuels caterpillar fungus gold rush” Press Release on how Tibetans devise a sustainable regulatory management plan

- Geoff Childs is an Associate Professor of Anthropology with Washington University in St. Louis

[MUSIC: Allen Toussaint “Yes We Can” from Our New Orleans (Nonesuch Records 2005)]

CURWOOD: Pollution detectives are finger-printing dirty water -

JACKSON: We use the isotopic signatures and the ratios of different elements to distinguish between conventional wastewater from oil and gas wells, and the newer hydraulically fractured wells.

CURWOOD: How forensic chemistry is helping solve fracking water mysteries, I'm Steve Curwood - and that's next time on Living on Earth from PRI.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Shannon Kelleher, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis, and John Duff. Our show was engineered by Jake Rego, with help from Tom Tiger, Noel Flatt and John Jessoe. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at L-O-E dot org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

CURWOOD: Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line anytime at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-99-88. Our e-mail address is comments at loe dot org – that’s comments at loe dot org. And visit our web page at Living on Earth dot org. That's Living on Earth dot org.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth