January 26, 2018

Air Date: January 26, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Extreme Weather Likely to Increase

View the page for this story

2017 brought devastating storms and wildfires to the U.S., costing lives and a record $306 billion. Penn State University climate expert Michael Mann tells host Steve Curwood that global warming is making powerful storms and drought driven wildfires more likely. But Professor Mann says this is not a “new normal,” because the planet has not reached a new climate stability. Instead humanity is now facing an ever-increasing threat of unpredictable and extreme weather. (12:34)

Extreme Weather an Extreme Risk

View the page for this story

The Global Economic Forum at Davos unveiled its list of major risks facing humanity in 2018. Since extreme weather events are seen as the most likely global risks, former US Vice President Al Gore and Papua New Guinea Prime Minister Peter O’Neill urged world leaders to act to curb greenhouse gas emissions. (01:32)

Credit-Worthiness in a Changing Climate

View the page for this story

The credit rating agency Moody’s Investor Services issued a company memo that outlines its plans to quantify the increasing risks posed by climate change. They’re part of a growing segment within the business world that wants to address global warming disruption in a more substantive way. Host Steve Curwood spoke with Andrew Teras, an analyst at Breckinridge Capital Advisors who rates communities’ credit worthiness, to find out how cities can address global warming and avoid a downgrade. (07:48)

Poetic Plea for the Marshall Islands

View the page for this story

The Marshall Islands’ thousands of residents are extremely vulnerable to climate change. Poet Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner describes life on the island and the threat from rising seas, and performs her poem “Tell Them.” (06:14)

Atomic Bomb Waste Could Leak into the Sea

View the page for this story

The U.S. military conducted nuclear weapons tests in the Marshall Islands in the 1940s and 50s, leaving a legacy of radioactive waste could be washed into rising seas. Australian Broadcasting Corporation reporter Mark Willacy tells host Steve Curwood that sea water is infiltrating the Runit Dome, an atomic bomb waste repository on a remote Marshall Island atoll. This poses a potential risk of radiation exposure for the small local population, though US experts insist its plutonium contamination levels aren’t dangerous. (15:18)

Pelicans at Pismo Beach

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Resident Explorer Mark Seth Lender watches the Brown Pelicans that gather at Pismo Beach in California to fish and preen, and finds them oddly graceful. (02:34)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Michael Mann, Andrew Teras, Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner, Mark Willacy

REPORTERS: Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Global leaders in Davos heard the most likely major risks this year will come from extreme weather events amplified by global warming.

MANN: The cost of inaction is already far greater than the cost of action. Imposing a price on carbon emissions is a much cheaper option than not doing anything and experiencing more of these devastating 300 billion dollar or greater annual tolls from climate change.

CURWOOD: It’s poor low-lying countries that have done the least to create global climate change that so far suffer the most.

JETNIL-KIJINER: Marshall Islands is only one meter above sea level and so we're extremely vulnerable to the rising sea level, and recently we've been having multiple floodings. Just within this year alone we've had four breaches.

CURWOOD: Leaders at Davos want rich countries to act quickly and fairly. That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Extreme Weather Likely to Increase

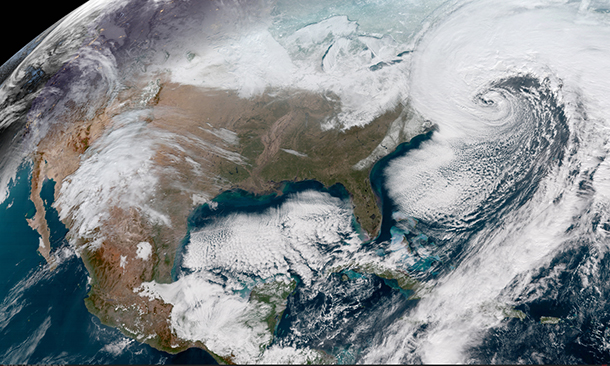

This January 4th Geocolor image from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) GOES-16 satellite captured the record ‘bomb cyclone’ nor’easter that battered the East Coast of the United States in January 2018. (Photo: NOAA)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Extreme weather events are the most likely major threats in 2018, and second only to weapons of mass destruction as risks with the potential of catastrophic impacts. That’s according to a study by the World Economic Forum, released at this year’s conclave in Davos, Switzerland, which, by the way, was disrupted by a record-breaking blizzard. We’ll have more on climate-related risk assessment later in the show, but first for a look at the science behind the dire weather predictions, we turn now to Penn State professor and atmospheric scientist Michael Mann. Michael, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MANN: Thanks. Great to be with you, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, what a lot of people want to know, including me, is: this past year we saw a lot of extreme weather that seems to be connected to the added effects of climate disruption – three killer hurricanes, there were these monster fires, the massive landslides. So, how much of what we saw this past year was just a perfect storm or how close are we to some sort of a new normal, do you think?

MANN: Yeah, well we probably won't be facing a new normal in the sense that a new normal implies that we reach some new sort of equilibrium and that's where things stay, whereas what we're looking at is an ever-shifting baseline. If we continue to emit these warming gases, greenhouse gases, into the atmosphere then the heat waves will become more frequent and more intense – droughts, wildfires, floods. We are seeing a taste of what's in store and there's no question in my mind that in the unprecedented extreme weather that we've seen over the past year, we can see the fingerprint of human influence on our climate.

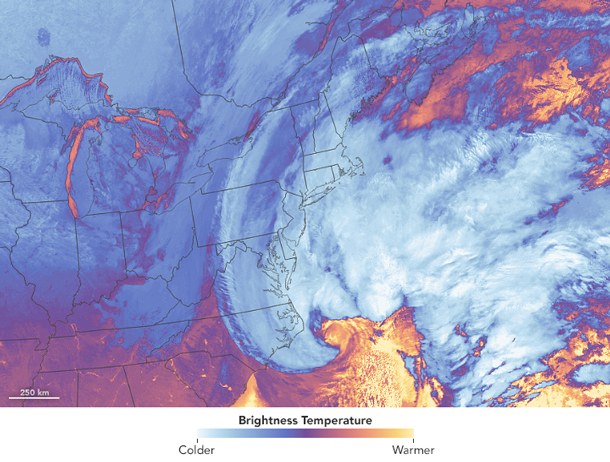

A January 4th NASA image of the record ’bomb cyclone’ nor’easter, showing infrared signals known as brightness temperature. This storm was fueled by warm, moist air rising from the Atlantic crashing into frigid Arctic air. (Photo: Joshua Stevens / NASA)

CURWOOD: I know you're a climate guy and not a weather guy, but looking ahead at 2018, what are the odds that we'll see as many of these really intense events as we saw last year do you think?

MANN: Yeah, sometimes it is difficult to really say where we go from weather to climate because climate change after all is changing the statistics of the weather. It's giving us more of these extreme events and we have every reason to expect that we will see more of that. We long predicted that as the Earth continued to warm, as the oceans warm, there's more energy to intensify hurricanes and to killer storms, there's more moisture in the atmosphere so when it rains it rains harder and you get more of those Harvey-like floods and the floods that California was dealing with just within the past couple weeks – it seems almost paradoxical. But even though the rainfall events become more intense, they become fewer and farther between and so you get more widespread drought, and California is still dealing with an ongoing drought despite the fact that they've had a few very heavy rainfall events.

The wildfires that we've seen on the west coast, again, you bring together extreme heat, extreme drought, you add Pine Bark beetles, which can live through the warmer winters and weaken the forests. All those things come together and to use the term you used previously a "perfect storm" of consequences for wildfire. So, the impacts of climate change are no longer subtle. We are seeing them play out now in the form of these unprecedented events.

CURWOOD: So, I keep wanting to ask you questions outside of your discipline. One is actually an economic one, professor. We saw this last year that there was an enormous amount of financial damage ascribed to these storms. It was north of $300 billion dollars, $306 billion dollars, which is more than the federal government spends on health care and education combined. Looking ahead at this year, I mean, what are the odds we might get hit with a tab like that again do you think?

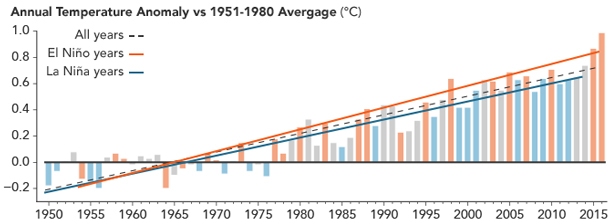

El Niño years tend to be warmer than other years, and global average temperatures are rising overall. (Image: NASA Earth Observatory chart by Joshua Stevens, using data from the Goddard Institute for Space Studies)

MANN: Well, unfortunately, you know, what we're doing is we're loading the dice so that we're favoring those odds, more of those extremely expensive $300 billion dollar seasons are going to occur. Think of them as sixes on the die, and we're seeing more and more of those sixes, and climate change is weighting the die towards those very damaging hurricane seasons, wildfire seasons and it's really important to realize that in the economic toll that climate change is taking – and no, I'm not an economist but some of my best friends are economists and I talk to them – and there is a lot of communication between these different communities – the climate research community, the economics community – because the problems that we deal with, the impacts of climate change and adaptations and the threat of climate change requires us to understand not just the science but the sociology, the economics, the ethics and everything else. And when you look at the economics of climate change, if you talk to the leading economists who study climate change mitigation, they will tell you that the cost of inaction is already far greater than the cost of action, which is to say doing something about the problem, imposing a price on carbon emissions, is a much cheaper option than the option of not doing anything and experiencing more of these devastating $300 billion dollar or greater annual tolls from climate change.

CURWOOD: Right now, how would you characterize the weather conditions in North America. I mean, to what extent is weather acting normal or kind of weird for wintertime?

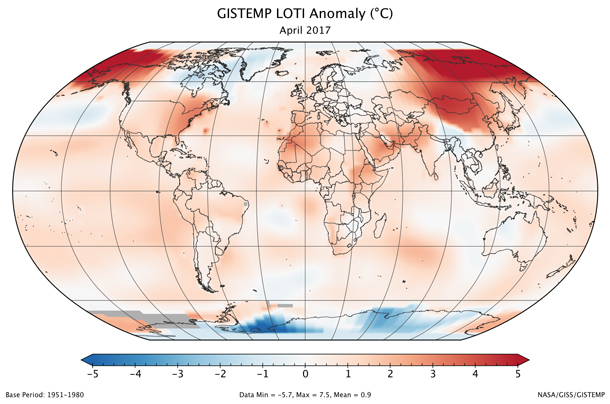

MANN: Yeah, well we're sort of experiencing weather whiplash right now where we're alternating here in the eastern United States between extreme cold and extreme warmth. Some people look at that, they see the unusual cold and they say, “Well how can there be global warming if we're experiencing unusually cold winter conditions?”, and the fact is that the science is actually pretty nuanced on this point, and even though we expect an overall warming in just about every region of the globe, that doesn't negate the possibility that when we do see these cold waves striking the US that in certain places we could see them strike even harder.

A couple weeks ago we had this unprecedented nor'easter, the strongest nor'easter on record now. It had a central pressure that ranked with many hurricanes in terms of the strength of this storm, but it's not a hurricane, it's an extra tropical storm. Unlike most extra tropical storms, though, these nor'easters gain a lot of their energy from the warmth of the ocean. Even in the winter, the ocean is relatively warm compared to the land, and also all that evaporation and relatively warm ocean water means there's a lot of moisture in those storms and that moisture is converted into massive snowfalls.

So, there's now some emerging science that suggests that warmer oceans like we've seen this season, a very warm Atlantic, when those cold air masses strike the warm oceans and you get those very large differences in temperature and you get all that evaporation from the warm ocean, that, as with a hurricane, leads to in a very intense storm. The more intense that storm, the stronger it's going to be spinning around, and where it's spinning around it's either bringing warm air up on one side or cold air down. The stronger these nor'easters become the more likely it is that we get these episodes of very cold air from the north crashing down into the interior of the United States. Yes, giving us increased cold extremes. So, it is indeed possible that we can see zero overall warming, but bigger extremes on both sides.

CURWOOD: Let's look at last year for a moment. How might those extreme weather events in 2017 have been related to the El Niño, La Niña cycle, if at all?

MANN: Part of what we're seeing, the wacky weather that we're seeing, stronger nor'easters, climate change is probably favoring those patterns in giving us some of the wacky weather that we're seeing, but on top of that the wildcard is of course, El Niño and La Niña, a natural oscillation in the climate system that also influences North American weather patterns in the winter. And detangling all of that is difficult because we think that the impact of El Niño on North America in the winter may itself be changing because of climate change, becoming less predictable.

So, in an El Niño year you would normally see a relatively wet Southwestern US, a dry Pacific Northwest, a relatively warm northern United States and a cool and potentially wet Southeastern United States. And a La Niña year, which is what we're sort of in this year, a weak La Niña, tends to be dry on the west coast, tends to be actually warm in the southeastern US. Well, that doesn't really fit the pattern of what we're seeing this winter. So, El Niño and La Niña may be having an impact, but that impact may be becoming more and more irregular and it sits on top of these other impacts that we think climate change is having.

CURWOOD: You scientists have talked about other oscillations in the weather system. I've heard about the Pacific decadal oscillation, oscillation as a weather flipping back and forth over the course of a decade. What's the thinking about that phenomenon these days?

Global temperature anomaly compared to 1951-1980 base period. (Photo: NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies)

MANN: So, there's still a fair amount of debate about this phenomenon, the so-called Pacific decadal oscillation. We already talked about El Niño, and El Niño is sort of this interannual oscillation. It takes place in time scales of three, four, five years. Well, there is sort of a longer term oscillation in that same system, the tropical Pacific Ocean and atmosphere can also interact on timescales that are a decade or longer. And that means you can have longer term regimes where the climate is more El Niño-like and longer term regimes a decade or more where it's relatively La Niña-like. In fact, we think that some of why the globe didn't warm as much as we expected during the first decade of this century, the 2000 to 2010 or so, it's sometimes been called the “pause” in warming or the “hiatus.” Well, that isn't really a good description as global warming continued. But what is true is the tropical Pacific sort of went into a cool phase for a little while, part of that Pacific decadal oscillation that did offset some of the global warming during that period.

The problem with an oscillation is if you live by the oscillation, you die by the oscillation. Now we may be seeing the flip side of that with an even greater rate of warming over this decade as that phenomenon maybe has flipped into a different phase. But it's really difficult to determine how much of that variation is just a simple internal oscillation in the system and how much of it has to do with the fact that there is an irregular pattern of volcanic eruptions and solar output varies on sort of the decadal time scale as well, and there are human impacts, greenhouse gases, but also pollutants that can have a cooling impact in some regions. All of this is happening at the same time. It's very difficult to detangle it all.

CURWOOD: Michael, this is a time when there's been a lot of pressure on federal research into climate disruption, the science side as well as taking action on the political side. What kind of risk does this put us at if we don't understand this more scientifically, if we don't address it politically?

Michael Mann is Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science at Penn State University. (Photo: Penn State University)

MANN: Well, the risk simply mounts as we continue to not act to the extent that we need to and there's some progress taking place, and the Paris Accord was a major step forward, but right now here in the United States, we don't have sort of the support at the executive level that we'd like to see for climate action and the risks are clear. They're not subtle any more. We're seeing them play out, $300 billion dollars in extreme weather and climate-related damage this last year that had the fingerprint of human impact on climate.

It doesn't stop there. If we continue not to act then the damages accrue. Pretty soon we commit to the melting of much of the Greenland ice sheet and the West Antarctic Ice Sheet and sea level that thus far had been limited to less than a foot starts to become measured in feet and then pretty soon in meters and yards. So, there isn't a new normal. Things get continually worse if we go down this highway. What we need to do is to take the earliest exit ramp that we can in the form of decreasing our emissions, transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann is a Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science and Director of the Earth Systems Science Center at Penn State University. Thanks so much, professor, for taking the time with us today.

MANN: Thank you, Steve, always a pleasure.

Related links:

- The Washington Post: “Extreme hurricanes and wildfires made 2017 the most costly U.S. disaster year on record”

- Scientific Reports journal article by Michael Mann on how extreme weather can be linked to climate change

- About Michael Mann

[MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nn5Px_GXstQ

Claude Hopkins, “Stormy Weather” on Swing Time, composed by Ted Koehler/Harold Arlen, Prestige Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up, why state and local governments could find it harder to borrow money if they don’t address climate risks. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth, keep listening!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Snorre Kirk, “Pastorale” on Stunt Records Compilation Vol. 25, 2017, Stunt Records/Sundance Music]

Extreme Weather an Extreme Risk

Former US Vice President Al Gore, center, talks about extreme weather risks related to climate change next to Papua New Guinea Prime Minister Peter O’Neill (left) and moderator Bronwyn Nielsen (right). (Photo: Screenshot from World Economic Forum video)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Snow is normal in Switzerland in January, but on January 22nd, a 20 year record breaking blizzard blanketed Davos, disrupting travel for people heading to the annual World Economic Forum. Appropriate, then, that the category of “extreme weather events” takes the number one spot on a list made by the forum of the most likely major global risks in 2018, ahead of “natural disasters,” “failure of climate change mitigation and adaptation,” and “water crises.” And the majority of those risks are related to climate disruption. A Davos panel called “Responding To Extreme Environmental Risk” featured former US Vice President Al Gore and the Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea, Peter O’Neill – and addressed the potential of climate to derail economies, communities, and the future.

The World Economic Forum’s “Responding to Extreme Environmental Risks” session took place on Wednesday, January 24th, 2018. (L-R Philipp Hildebrand, vice-chair, BlackRock;Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, Co-Chair Indigenous Peoples Forum on Climate Change; Papua New Guinea Prime Minister Peter O'Neill; Former US Vice-President Al Gore)(Photo: screenshot from World Economic Forum video)

O’NEILL: The world seems to think that they’ve got time on hand. They forget to realize that there are real communities out there who are suffering as a result of these change in weather conditions. And it affects the most poorest first, and those who cannot speak. And this is the unfortunate thing about climate change, is that the most exposed are the countries with the smallest population, the smallest budgets, and the poorest families.

GORE: It is getting worse. We still have the ability to take back control of our destiny as a species, but we do not have time to waste. We need to get moving on it.

CURWOOD: Former US Vice President Al Gore, along with Papua New Gunea Prime Minister, Peter O’Neill.

Credit-Worthiness in a Changing Climate

A waterfront view of Miami, Florida. (Photo: Matthew Hurst, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Climate-related disasters can cost a lot of money. The monster hurricanes, huge fires, floods, and droughts of 2017 cost more than $300 billion in damages in the US alone, stressing state and local government budgets, as well as the Trump Administration. And now the agencies that rate the ability of states and communities to pay back money borrowed in the form of bonds are beginning to consider how well those jurisdictions are prepared for climate extremes and instability. Moody’s Investor Services recently unveiled standards they plan to use to integrate climate risks into their ratings for bond issues. To discuss how this could affect communities we turn now to fixed income expert Andrew Teras of Breckenridge Capital Advisors in Boston. Welcome to Living on Earth Andrew!

TERAS: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you guys look at climate disruption in your own analyses?

TERAS: We've been integrating what's called ESGs, so environmental, social and governance factors, into our traditional credit analysis for about six or seven years now. What I mean by that, so traditional credit analysis would be when you're looking at, you know, the riskiness of a borrower. You might look at their financial statements, so how much cash do they have in the bank? You might look at their debt. How much debt do they have relative to the resource base, so the tax base? What we do here is sort of take those traditional credit metrics and then we layer on top of that this concept of ESG, and so we're looking at a broader spectrum of risk.

CURWOOD: So here we are near Boston Harbor, also not too far from our studios. How safe are we here, the fourth floor of this building?

TERAS: Certainly, this is an area that is subject to the risk of coastal flood events, but what we would do is say, “Looking at the city of Boston as a whole, what portions of the city relative to the total size of the tax base are exposed?” And so the answer is for Boston right now, this is absolutely at risk, but when you look at Boston versus some other communities, maybe that might be a little smaller, maybe have less in terms of the resource base, Boston has more resources to be able to manage this type of problem.

CURWOOD: Why would a credit agency like Moody's care about climate risk?

TERAS: They would care about it because these types of risk can have direct impact on the ability for a city to pay its bonds, pay its, you know, its credit holders. And so, in a lot of cases when a city issues bonds, what it's pledging you, what they're saying they're going to pay you back from, is from your property tax base, and property tax base is obviously a function of property values. To the extent that property values continue to decline, or, you know, start to decline or decline more rapidly, that can have huge implications for a budget and the less money that's available for essential services, so police and fire, the less money there's going to be available to pay back investors. Now, of course the issue that I think a lot of folks are having to sort of grapple with is, you know, not necessarily that climate change doesn't exist, but how fast is it going to impact and then even if it does come fairly fast, how severe are these problems going to be and what parts of the country are going to be impacted more than others.

A poor credit rating from a major firm like Moody’s Investor Services could affect a state or local government’s ability to borrow money for infrastructure projects. (Photo: Isaac Wedin, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, what kind of signal is Moody's sending to municipalities, coastal towns, places vulnerable to tornadoes or wildfires. What are they suggesting could happen?

TERAS: They're sending a pretty significant message, and we welcome it. As investors, we definitely appreciate this because the more attention paid to these types of issues, the more likely that meaningful actions are going to be taken to mitigate some of these risks, and there are a lot of ... in many places across the country, a credit rating is an important thing. It allows them to access the capital markets or borrow for infrastructure projects at a reasonable interest rate. What the rating agencies are sort of telling us here is that we are starting to move to a point where we may take action, rating actions, so lower your credit rating, if you are not attuned to these risks. So, this could be pretty pretty significant going forward.

CURWOOD: Now, Moody's has come up with this report. What about the other credit rating agencies – Standard and Poor's, Fitch – how have Moody's competitors responded to this if at all?

TERAS: All three of them have responded for sure. The Moody's piece was a little bit different in that it actually was presenting sort of quantitative measures of how we can evaluate the risk. The other two rating agencies, at least from our perspective, it was a little lacking. It was highlighting the risks, but not telegraphing specific metrics that they're going to use to measure the risk, which is a little less helpful to the market. At the same time, it's a good sign because it means that behind the scenes they're thinking about this stuff, and we are moving light years from where we were even two, three years ago on this issue.

CURWOOD: So, what are you seeing change in the attitudes of cities and states regarding the issue of global warming over these past few decades?

TERAS: There are many communities across the country that really are not thinking about this risk at all. But there are a lot that are starting to think about it, and to the extent that cities, to the contrary, they're not attuned to this risk, you're going to get a lot of questions from a lot of people, investors included, about why you aren't factoring in these risks into your planning or what you're doing about these risks, and if investors don't get answers in terms of at least you're thinking about them, they could demand higher interest rates to lend you money.

CURWOOD: So, in the Moody's report, they don't point to any particular place that has faced a downgrade as a function of climate change. So, how ... what's your thoughts about how far this report goes? Is it far enough for municipalities to get the signal they better start doing something about that or are they going to have to see either a real downgrade or a direct threat of a downgrade to take action?

Andrew Teras is a Senior Research Analyst at Breckinridge Capital Advisors. (Photo: Breckinridge Capital Advisors)

TERAS: I think this might put this on the radar of more communities across the country, but you're not going to see significant action, I don't think, until the rating agencies start paying attention a little bit more in terms of actually saying, “We are lowering your rating because of these risks,” but there's other ways in which, you know, we think that communities – their ears could perk up – outside of what the rating agencies are doing in terms of like borrowing costs. You see this in some parts of the country: To the extent that the insurers there are no longer willing to provide reasonable premiums. Well, that can have a huge impact on the property values.

CURWOOD: So, what else needs to happen on a policy level beyond credit for the municipalities to really start preparing for climate disruption do you think?

TERAS: I think buy-in from all levels of the government and so that starts from the top. So, the mayor or the city administrator. If those folks are not buying in that this is a material thing that needs to be addressed, you're really not going to have success. So, or maybe the city council, for example, needs to need to have buy-in there. So, I think it has to happen from the top down and it needs to pervade really everything that goes on, and the other thing I think is that those folks need to promote this issue amongst their constituents, amongst the business community where they live.

CURWOOD: Andrew Teras is a Research Analyst at Breckenridge Capital Advisors in Boston. Andrew, thanks so much for taking the time today.

TERAS: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Bloomberg: “Moody’s Warns Cities to Address Climate Risks or Face Downgrades”

- Breckinridge Capital Advisors

- Andrew Teras Company Profile

[MUSIC: SambaDa, “Casa de Mainha” on Gente!, Cali-Bahia Records]

Poetic Plea for the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands are threatened by rising seas. (Photo: BermudaMike, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: For some nations, climate disruption poses an existential threat right now. Topping that list are low-lying countries already losing acres to rising seas such as Bangladesh and the many small island states, including the Maldives and Marshall Islands. These islands have long demanded action to curb global warming gas emissions at the United Nations, perhaps most prominently at the December 2015 Climate Conference when the Paris Agreement was forged. And the words spoken in Paris by a Marshall Island poet still resonate.

JETNIL-KIJINER: My name is Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner, I’m from the Marshall Islands. The Marshall Islands is in the Northern Pacific Ocean and it's in an area called Micronesia. It's a small country, it's not very developed. You know, there's just one road, like just one main road, running through the entire island. There's no traffic lights, there’s no malls, there’s no Burger King, MacDonald’s, none of that happens there. It's very very flat, there's no mountains at all, it’s just ocean all around you, which I heard people say that kind of scares them.

[SOUND OF GENTLE WAVES]

It freaks them out when they're first there, like everywhere you turn you see the ocean. And there's coconut trees. Some parts are really lush and beautiful, some parts are not. Our people were known to be canoe navigators, we're also known to be really fine mat weavers. And there's just kids everywhere.

[SOUNDS OF KIDS PLAYING AND WAVES]

You just see kids running around all over the place. Basically, Marshall Islands is only one meter above sea level and so we're extremely vulnerable to the rising sea level. And so we’re extremely vulnerable to the rising sea level. We have these things called, like, sea walls, which are walls we built to keep the ocean out of their homes, and recently we've been having multiple floodings. Just within this year alone, we've had four breaches ... water being so high that it would crash into our homes, destroy, completely obliterate and destroy homes, like completely level it out.

I was out two weekends ago, you know, running errands, and I saw these women and children fundraising with a car wash and BBQ plates, and so I went to buy a BBQ plate. And I said, "What are you fundraising for?" And the women, said, “Our sea walls are broken,” and I was like, "Oh, from the recent flooding?" And they said, “Yes, just the recent one. It broke all of our sea walls." It was a whole community of houses whose sea walls were broken. And they sent me all of these photos, you know, of these completely messed up sea walls, parts of their houses just like totally messed up. And you know, they're not rich, these people. They're having to figure out ways to fix their sea walls, raise funds. Our minimum wage is $2 dollars an hour. And so we're already struggling as it is, as a people, you know, as a country. But then, we have climate change on top of this and it just exacerbates the situation.

I'm a poet and a performer. I'm actually here with the Global Call for Climate Action. GCCA brought me and four other poets out here for the Spoken Word for the World project to raise awareness on various issues on climate change. Our poetry is meant to bring the humanity back into the issues that we're discussing.

TELL THEM

I prepared the package

for my friends in the States

First, the dangling earrings woven

into half-moons, black pearls glinting

like an eye in the storm of tight spirals

Second, the baskets

sturdy, also woven

brown cowrie shell shiny

intricate mandalas

shaped by calloused fingers

Inside the basket

I write a message:

wear these earrings

to parties

to classes and meetings

to the corner store, the grocery store

or while riding the bus

Store jewelry, incense, copper coins

and curling letters like this one

in this basket

And when others ask you

where you got this

you tell them

they're from the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands are comprised of 1,156 islands and islets. (Photo: Keith Polya, CC BY 2.0)

show them where it is on a map

tell them we are a proud people

toasted dark brown as the carved ribs

of a tree stump

tell them we are descendants

of the finest navigators in the world

tell them our islands were dropped

from a basket

carried by a giant

tell them we are the hollow hulls

of canoes as fast as the wind

slicing through the Pacific sea

we are wood shavings

and drying Pandanus leaves

and sticky bwiros at kemems

tell them we are sweet harmonies

of mothers, aunties, sisters

songs late into night

tell them we are whispered prayers

the breath of God

a crown of fuchsia flowers encircling

Auntie Mary’s white sea-foam hair

tell them we are styrofoam cups of Kool-Aid red

waiting patiently for the ilomij

we are papaya-golden sunsets bleeding

into a glittering, open sea

we are skies uncluttered

majestic and sweeping in their landscape

tell them we are dusty rubber slippers

swiped

from concrete doorsteps

we are the ripped seams

and the broken door handles of taxis

we are sweaty hands shaking another sweaty hand in heat

tell them

we are days

and nights hotter

than anything you can imagine

tell them we are little girls with braids

cartwheeling beneath the rain

tell them we are shards of broken beer bottles

burrowed beneath fine white sand

we are children flinging

like rubber bands

across a road clogged with chugging cars

tell them

we only have one road

Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner is a Marshallese poet, writer, performance artist, and journalist. (Photo: Simon Ruf/UN Social Media Team, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

and after all this

you tell them about the water

tell them how you have seen it rising

flooding across our cemeteries

gushing over our seawalls

and crashing against our homes

tell them what it's like

to see the entire ocean level with the land

tell them

we are afraid

tell them we don't know

of the politics

or the science

but we see

what's in our own backyard

tell them some of us

are old fishermen who believe that God

made us a promise

tell them some of us

are a little bit more skeptical

but most importantly you tell them

that we don't want to leave

that we've never wanted to leave

and that we

are nothing without our islands.

CURWOOD: Marshall Islands poet Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner with her poem, "Tell them," recorded at the 2015 Paris Climate Conference. President Trump has moved to leave the Paris Climate Agreement, making the US the only nation outside the compact, though that will take until 2020.

Related links:

- More spoken word poetry by Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner

- NBC: Pacific Islander Poets Use Art, Stories to Urge Climate Action at UN Conference

- The New York Times: The Marshall Islands Are Disappearing

- LiveScience: Was Darwin Wrong About Coral Atolls?

[MUSIC: Jan Johansson, “Visa fran Utanmyra” on Jazz Pa Svenska, Heptagon Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up, how a changing climate and a nuclear legacy are combining to put the Marshall Islands in jeopardy. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth, stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies – combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning in to the Race to 9 Billion podcast, hosted by UTC’s Chief Sustainability Officer. Listen at raceto9billion.com. That’s raceto9billion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jan Johansson, “Visa fran Utanmyra” on Jazz Pa Svenska, Heptagon Records]

Atomic Bomb Waste Could Leak into the Sea

The Runit Dome on Enewetak Atoll contains chunks of plutonium from misfired atomic weapons, radioactive soil, and other debris from the nuclear testing that took place there between 1946 and 1958. (Photo: Greg Nelson)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. “We are nothing without our islands,” wrote poet Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner but, the Marshall Islands face uncertainties beyond the rising seas. In the 1940s and ’50s, these remote coral atolls were ground zero for atomic weapons testing, and now the sea is infiltrating a nuclear waste dump. Islanders evacuated from Enewetak Atoll were allowed to return in the 1980s, but as Mark Willacy of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation documented, the encroaching ocean is raising concerns about contamination from nuclear weapons waste. He joins me now from Brisbane – Mark, welcome to Living on Earth!

WILLACY: Thanks, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, where is the atoll? And what is it like?

WILLACY: Well, the atoll is in the central Pacific, basically in the Marshall Islands. And obviously the Marshall Islands is this huge expanse. It's over a 1,000 islands spread over 2,000 square kilometers so, it's in one of the even most remote parts of the Marshall Islands in the far west of the country, and to get there is a feat in itself, Steve, put it that way. We had to hire an old prop plane and fly across a 1,000 kilometers of open ocean and land on an old US military air strip. And it's a beautiful place, it's just extremely remote, extremely isolated.

CURWOOD: So, what are we talking about in terms of people who live there or near there?

Willacy describes the concrete cap over nuclear waste as looking like an extra-terrestrial flying saucer. (Photo: Greg Nelson)

WILLACY: Well, before we got there, we were told that there’s a population of about 600, but when we arrived it appeared that the population was no more than 200, and we did ask around about what had happened to the population. A lot of people do move away for work. There is no work on the island, and so there’s a very small population there and they do feel quite isolated given that the air services are not regular, the barge that brings over their supplies is not regular. You really do feel like you're on the – at the end of the Earth.

CURWOOD: So, what happened on Enewetak during the nuclear testing?

WILLACY: Well, obviously Bikini Atoll is probably the most famous site of the US nuclear testing. Now, Bikini is about 300 kilometers to the east of Enewetak, but in fact, at Enewetak there were more nuclear tests than Bikini, in fact, nearly double the amount of nuclear tests between 1946 and 1958. There were actually 43 nuclear detonations during that period, including some of the largest bombs ever detonated, some thermonuclear devices, some so big they vaporized entire islands. So they were extremely toxic. In fact, we found an old NBC report from the ’70s during the cleanup of those islands, and it made the point that it was the most toxic place on Earth.

CURWOOD: Mark, why is there a dome filled with nuclear waste on this low lying Pacific atoll?

WILLACY: Well, it's a good question. Before the nuclear testing started in 1946, the US military moved all the people off in Enewetak like they did at Bikini Atoll. Now, they detonated all these nuclear devices, and over the period, the people wanted to return, and so the United States decided in the 1970s that it would launch a cleanup of parts of the atoll, so they could at least get some of the people back on some of the islands. So, in 1977, about 4,000 US servicemen was sent in to clean up as many of the islands as they could, essentially. And one of the ideas that they had was to throw a lot of this old radioactive debris, soil, bits of plutonium, in fact, from a misfired bomb, into a crater caused by one of the detonations, and so that's what they did. In over a three to four year period, they basically put, I think it was 85,000 cubic meters of radioactive soil and debris into this all crater and then they decided to cap it. Now, to cap it they put about a foot and a half thick concrete dome over the top, and if you look at this thing from the air it looks like one of those 1950s flying saucers that crash-landed on this remote Pacific atoll.

The Runit Dome, itself built on top of a detonation crater, lies next to another one of about the same size. (Photo: Greg Nelson)

CURWOOD: Now, you mentioned plutonium. So, plutonium isn't hyper radioactive. You could be shielded from it, but, boy, if the tiniest amount gets into water or into people, into living things, that's it. It's really highly toxic.

WILLACY: That's right it has a radioactive half-life of about 24,000 years. So, this plutonium was actually created or spread around the atoll in the northern islands by the misfiring of a bomb. So, in other words this nuclear device did not detonate the way it was supposed to detonate, and there were 400 chunks of this plutonium spread across the island, and again, in the 1970s when these US servicemen were sent there to clean it up, they told stories of having to go and put it into plastic bags and then they threw these plastic bags into this bomb crater that was then capped with the dome. So, it is highly toxic. I believe about a one millionth of a gram is enough to kill a human being, so it's something that you certainly do not want to be exposed to.

CURWOOD: No, you certainly no want to inhale it or touch it. So, of course, the atoll is at sea level. So, how much have sea levels risen at Enewetak and why is there now concern about water infiltrating that dome that's capping the nuclear waste?

WILLACY: Yeah, the Marshall Islands, one of the most low-lying countries on the planet. They have an average height of six feet above sea level, so you're talking about a country that is at the forefront at the fight against climate change, and we've seen big storm surge events, other types of flooding in the Marshall Islands, that has seen water, sea water, come clean across some certain atolls. Now, at Enewetak when they built this dome in the late 1970s, it was obviously no factoring in climate change and sea level rise is caused by climate change. So, it was built right next to the shore on the ocean side of this island in Enewetak and seawater is penetrating the underside of the dome because when they threw all this material into the old bomb crater they didn't line the old bomb crater with anything. They were supposed to line it with concrete, but that never happened because of cost considerations.

So, as the sea level has risen, the groundwater level has risen and therefore you have groundwater penetrating inside the dome because a lot of this atoll is obviously sand, it's coral, it's permeable material. Not only that, the United States itself in a 2013 report, a government report, warned that this dome could smash apart because of the increased ferocity of typhoons and other big storm events, not that the Marshall Islands is the recipient of too many of these typhoons, but they do get the odd typhoon that causes trouble, so the dome is really very vulnerable to climate change, and this is something the Marshall Islanders themselves have been really trying to reinforce for years, and to try and get lawmakers in the United States to take up their call.

Enewetak Atoll is a collection of 40 islands in a ring atop an extinct, sunken volcano in the Pacific Ocean. (Photo: NASA/USGS)

CURWOOD: So, if a typhoon did hit Enewetak, what would happen to all that contaminated material inside the dome?

WILLACY: Well, if it was to be breached or there were some sort of catastrophic failure of the dome ... there have been written warnings, again, this government report in 2013 that that could see radioactive material sort of leeching out in large quantities. Having said that, the United States government has also said, “Look, if there was this catastrophic breach of the dome, and this material was to wash out, we do not believe that it would cause any greater environmental damage to the outside environment that has already being caused by the bomb tests.” In fact, the lagoon formed by the Enewetak atoll, the second largest ocean lagoon in the world, has a lot of plutonium in the sediment, in the bottom of it, and the United States government is saying, well, look the dome, yes, it serves a purpose, but if it was to be breached, we doubt it would create much more damage. Now, you talk to Marshall Islanders and they say, Well, why build the dome in the first place ... it's obviously got plutonium in it, it's highly toxic, we do need that contained and if that was to spill out, well, we're the people who would have to be evacuated once again from Enewetak which is our island home.

CURWOOD: So, who has checked into the US government's claim that if the dome breaks up there won't be a contamination problem there at Enewetak?

WILLACY: We've got the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory based out of California. They have been doing groundwater-monitoring tests at Enewetak. They have installed in recent years a number of monitoring facilities, and you can see these pipes that come out of the dome and outside of the dome, but in terms of dealing with the structural issues of the dome itself, there's been no moves to try and reinforce the dome, to try and make sure that the concrete can withstand a big typhoon or a big storm event. Now, that's going to cost potentially hundreds of millions of dollars, and for the Marshall Islanders to do it themselves would be impossible. This is a small Pacific nation, quite impoverished by Western standards. So, it really is not just an environmental problem, it's a political stalemate as well.

CURWOOD: So, how has all this radioactivity affected the health and livelihoods of the people who live there?

WILLACY: The health impacts were largely mitigated by the fact that the people were taken off the island ahead of the nuclear testing. I think the Marshall Islanders who were most affected by the nuclear testing weren't the people on Bikini or Enewetak where the testing was taking place because they were taken off the island. You did have some very severe health impacts from islanders who were downwind of a couple of the biggest bomb tests, including the largest nuclear detonation the United States ever carried out, and that was a bomb called Castle Bravo that was detonated at Bikini. The wind calculations were wrong and the wind blew over an island called Rongelap, and the people were there for four or five days before the United States military evacuated them, and a lot of people became very ill. After that, there were cancers detected. There are even reports of birth defects among the children.

Nuclear weapon test of “Mike,” the first hydrogen bomb ever tested, on Enewetak Atoll. (Photo: National Nuclear Security Administration /Nevada Site office)

But in terms of the people of Enewetak where we were visiting, there was no great evidence or examples of problems with health. Having said that, the islanders did introduce us to a couple of the children who they say have some sort of disabilities that are associated with exposure to radiation through soil and food. Now, we're not scientists and we're definitely not trained in radioactivity and contamination, but on the island itself of Enewetak, I suppose to give you an example of the fact that people are being monitored, is a laboratory set up by the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory. And it has a whole of body count radiation machine there that if you do go to one of these contaminated northern islands, you are supposed to come back, you are supposed to get checked through this body counter machine. However, while we were there there was a problem with the hard drive and it hadn't been operating for some weeks as far as the locals were telling me.

CURWOOD: So, of course, there's various kinds of radiation there, but much of it will be around literally for thousands of years, so it's not like ignoring this means that it'll go away. So, what could be done at this point about this leaking dome?

WILLACY: Well, what the Marshall Islands government would like to see is the United States take responsibility for what it sees as a United States problem. Now, the United States in 1986 did a deal with the Marshall Islands, that the Marshall Islands would take over the running of its own affairs. It paid the Marshall Islands about $150 million dollars, and said, “Right, all deals are done, there's no more claiming of compensation or anything like that.” So, from the perspective of some in the United States government, there is no obligation of the United States to – to come back and clean up this dome or to fix it up. So, I think we're at a political stalemate, as I said before, Steve, and that's the problem.

The Marshall Islands as a nation has very little clout in any international forum at all, let alone when it's dealing with one of the most powerful nations on Earth. They have tried through a number of lawmakers in the Congress to get bills put forward. I believe they have been unsuccessful. So, I think we're just at a situation where the Marshallese are warning, look, right, well just wait for this thing to crack open or to smashed totally apart, and then, I suppose we'll go in and we have to evacuate the people of Enewetak again. Look, there's only a few hundred of them. Why would the world care?” Unfortunately, this is a nation where its nuclear legacy is colliding directly with the climate change future and that dome is the intersection of all of that, and they've got young activists in the Marshall Islands trying to take up the fight and they're saying, “Look, it's amazing. I'd rather live on a nuclear contaminated island than no island at all.” The Runit dome, as it's called, is already very much in the firing line of these rising seas.

The Marshall Islands’ entire territory lies within a few feet of current sea level, and projected sea level rise under the most likely climate change scenarios will inundate the island nation. (Photo: Stefan Lins, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: What do Marshall Island attorneys, what do the lawyers say might be recourse against the United States at this point?

WILLACY: Well, that's a good question. We did actually go to the nuclear claims tribunals in the capital Majuro while we were there, and that has basically run out of funding. Now, that funds victims of the testing, that of people who have lost their homes, who have health claims to put against the United States government. It made $2.3 billion dollars worth of claims, however, only a few million dollars was ever handed out. So, if they can't even get justice for the health issues and for losing their homes, then I doubt that they're even going to try and launch any sort of suit against the United States government for some sort of redress or some sort of compensation or some sort of monies to try and reinforce the dome. I think the Marshall Islanders know they've lost, and you go into the nuclear claims tribunals there in Majuro the capital and there's just boxes and boxes and boxes of claims just gathering dust that will never be acted upon, and I think that's a great visual symbol of where the United States is in terms of how it fulfills its obligations.

CURWOOD: Some might say this is criminal.

WILLACY: Some Marshallese certainly say it's criminal, but again the United States said, look, we did a deal in 1986 with the Marshall Islands government to basically grant them independence and they gave them a check for $150 million dollars and said, right, that's it, deal is done, we'll leave it at that.

CURWOOD: Sounds like they were tricked because if they were still a territory of the United States they would be in a much stronger position.

WILLACY: That's exactly right, and they point to – to the United States itself, and they point to the downwinders, those people in places like Nevada who were exposed to nuclear fallout from the atomic testing program on domestic soil, and the fact that those people in Nevada – and I believe other places like Arizona even – were swiftly compensated and compensated much more generously than the Marshall Islands people. So they do feel like second class citizens, they do feel like the Americans took care of their own, and just left them dangling, if you like, and to deal with this toxic legacy.

CURWOOD: Mark Willacy is a reporter with The Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Mark, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

WILLACY: Many thanks, Steve!

CURWOOD: We contacted the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Livermore Labs, which has assessed the structural soundness of the nuclear dome along with independent experts. The lab says external cracks don’t affect the solidity of the protective cover but will be repaired during 2018.

Related links:

- “The Dome,” the documentary Mark Willacy did reporting for

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation: “A poison in our island”

- The 2013 Lawrence Livermore report describing the state of the Runit Dome

- U.S. Department of State: U.S. Relations With Marshall Islands

[MUSIC: Rokia Traore, “The Man I Love” on Tchamantche, composed by George & Ira Gershwin, Nonesuch Records]

Pelicans at Pismo Beach

Living on Earth’s Resident Explorer, Mark Seth Lender, writes about an encounter with one of the animal kingdom’s most skilled fishermen: the Brown Pelican. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: From the gentle lapping of waves on the Marshall Islands in the South Pacific we head now to the California coast, between San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara. That’s where our explorer in residence Mark Seth Lender watched some remarkable birds on the beach as the sun set.

A Brown Pelican stretches its neck, showing off its throat pouch, which it uses to capture fish. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Pelicans at Pismo Beach

Brown Pelicans

© 2017 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

LENDER: On a narrow stab of Pismo Beach the waves come in a palm-flat wash, all gold in the tops, where the green sea meets a dazzle of sand. Over the long swell, low as a breeze brown pelicans arrive as is their custom. They land running on their feet. They turn into the wind. And then begin their evening preening.

Screening their feathers for the least unkempt, the slight misalignment that might deflect their path of flight. When it matters most. That tight control, wings in an origami fold as they plunge, headlong, into the wide-ranging ocean; when whitecaps are torn free and they disappear into the foaming; or the calm so flat it shatters into shards. Oh the little fishes pooling beneath, drawn into a tangled ball to confuse what upwells from the blind deep; they had no idea how easy it would be for pelicans to unwind the Gordian knot of them, sharply from above.

A Brown Pelican heads towards a safe roosting spot, out of view from the shore. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

The sun is lower now, and lower still. Pelicans blink in the horizontal light. They stretch each disparate part:

- Legs as long as ballerinas and even the toes of their webbed feet pointing.

- Wings like awnings cranked out as far as they will go.

Pelicans preen themselves on the beach. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

- Their mouths agape like inflatable funhouse doors, yawning, the strange translucent pouch slung from the hard lower bill stiff as the gaff on some imaginary sailing ship, one that sails on air…

Now the short takeoff into the wind. Brown pelicans, low over water, as the night settles in like wetted silk. Sure as a binnacle compass they will find a safe roosting place, a shoal of rocks, somewhere out, that cannot be seen from the high point of the shore.

[MUSIC: Pete Siers Trio, “Mood Indigo” on Those Who Choose To Swing, composed by Duke Ellington, PKO Records]

CURWOOD: That’s our explorer in residence, Mark Seth Lender. And for his photos, glide on over to our website – loe dot org.

[MUSIC: Pete Siers Trio, “Louisiana” on Those Who Choose To Swing, composed by Ned Miller/Jule Styne/Bennie Krueger, PKO Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari and we welcome Hannah Loss aboard as a new intern this week. Special thanks to Shore Cliff Hotel, Pismo Beach.

Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org – and like us, please, on our Facebook page – it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth