May 4, 2018

Air Date: May 4, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Late Spring Imperils Birds

View the page for this story

April 2018 was the coldest and snowiest April on record for much of North America. That spelled trouble for migrating birds who arrived in the north expecting to bulk up on the spring emergence of bugs and found 2 feet of snow instead. Host Steve Curwood talks with Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Andrew Farnsworth about climate volatility and how unseasonably cold spring weather challenges migrating birds. (07:53)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

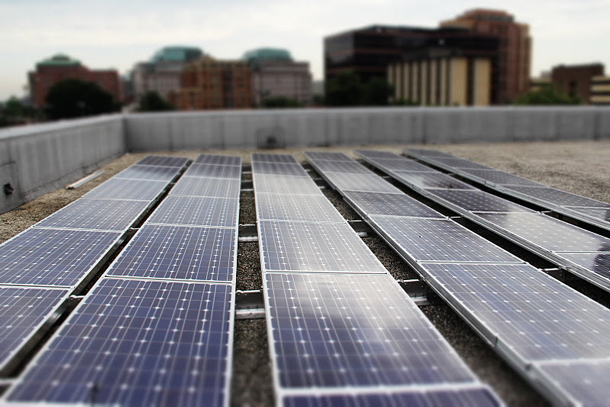

This week, Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood look Beyond the Headlines at rooftop solar power, embraced and encouraged in Hawaii but under negative pressure in South Carolina’s legislature. A look at history reminds that energy fights are nothing new, as the pair recall the 1977 protest at the construction site in NH of Seabrook Nuclear Plant. (03:49)

Champions for Children and Corals

View the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood continues our coverage of this year’s Goldman Environmental Prize with the winners from Europe and the Island Nations. Filipino Manny Calonzo took on the neurotoxin lead in paint, ubiquitous in his home islands, and won agreements to phase it out by 2020. And safe fishing activist Claire Nouvian of France launched a campaign to end coral-smashing deep-sea bottom trawling in the EU which achieved a ban of trawls below half a mile deep. (15:22)

BirdNote®: Whooping Cranes

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

The world’s remaining totally wild flock of critically endangered Whooping Cranes dances at its summer home in Canada’s Wood Buffalo National Park. Michael Stein takes us to there in today’s BirdNote®. (02:11)

Kerala’s Ambitious Organic Pledge

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

We kick off our series on the food and water challenges facing the tropical Indian state of Kerala. Rising rates of cancer there alarmed doctors and the public, and many blamed high levels of chemicals in food. So now there’s a government campaign to make Kerala’s food supply all organic by 2020. Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer takes a trip to Kerala to discover what’s involved. (17:48)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Andrew Farnsworth, Claire Nouvian, Manny Calonzo

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Michael Stein, Helen Palmer

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. “God’s Own Country.” That’s what they call the south Indian state of Kerala with its tropical climate and abundant harvests. But there’s a high incidence of cancer blamed on chemicals in food.

PRABAKHAR: We have found that lots of pesticide residue are there on vegetables, then antibiotics on meat and poultry, and the medical community agreed this is one of main reasons for the cancer. Kerala has a high incidence of cancer.

CURWOOD: The communist state government set an ambitious target to grow all its food locally and organically by 2020 – but there are naysayers.

VIJAYARAGHAVAN: No actually, I wouldn’t support total organic cultivation because once the disease occurs no bio control agents are going to be effective. So in such cases you have to resort to chemical pesticides.

CURWOOD: Fighting for healthy food – and at last it’s springtime for the birds. We have that and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Late Spring Imperils Birds

A migrating flock of snow geese. Snow geese travel more than three thousand miles from traditional breeding areas to their breeding grounds in Arctic tundra. (Photo: Steve Corey, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Migrating songbirds have finally found the springtime weather in North America they need to survive and thrive, but only a couple of weeks ago they had to fight unusual cold and deep snows in the Northern states. It’s all part of climate disruption, with many heightened gyrations of wet and dry, cold and warm around the world that worry bird experts like Andrew Farnsworth. He’s a research associate at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and says this Spring, most long-distance avian travelers felt the effects of extreme weather. That includes one of my favorite migrating birds, the Scarlet Tanager.

[SCARLET TANAGER SINGING – Cornell Lab of Ornithology All About Birds. New Jersey, May 8, 2011 (c) Benjamin M. Clock]

FARNSWORTH: So, Scarlet Tanager is a really cool, quite long-distance migrant. So, that's a bird that spends most of its life in the tropics. They're breeding in the US for a pretty short period of time, but this is a bird that's traveling one way, certainly several thousand kilometers. They're also flying across the Gulf of Mexico. They're one of these birds we call trans-Gulf migrants. Males are brilliant scarlet red with black wings, and certainly a bird that many many birders are hopeful to see every spring.

CURWOOD: So, how does this unusual cold and snowy spring...how has that affected migrating birds in those areas that have been fairly frosty?

FARNSWORTH: Birds, they're arriving to an area where the expectation is, “I’m going to be able to forage and find insects easily,” and to arrive at a place like that and find two and a half feet of snow obviously could pose major problems for finding food and sort of maintaining energy and fuel resources to continue migrating further.

CURWOOD: How fatal is this business of having snow on the ground in these places?

The scarlet tanager migrates across the Gulf of Mexico each year. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

FARNSWORTH: It can be quite fatal. It may be that perhaps if conditions are not so horrible that birds are able to bounce back and perhaps it just means a slight decrease in productivity, maybe not all individuals are able to produce young that year. But in severe cases like this year – or what seem like severe cases – where the cold is pervasive and the snow is pervasive, that could be a major hit to the population.

CURWOOD: Now I spend a fair amount of time in the Northeast where black flies are really annoying and mosquitoes are, you know, itch-provoking, and I have to remind myself that this is bird food so that I should be happy that these insects are there. Talk to me about the relationship between migrating birds and the spring insect emergence.

FARNSWORTH: The idea is that the timing of migration relative to that explosion of insects is going to have some direct connection to how successful you are as an individual. So, as an individual bird arriving to to some place where there are black flies everywhere, you can produce a lot of young and something about your timing of migration and where you go is genetic. Obviously producing more young that do the same thing, you're going to be able to take advantage in theory of that same flush of insects, assuming it happens at the same time every year.

Now, if it's changing, if it starts to shift because it's an extremely cold winter and the spring is cold and the ground is frozen and the black flies aren't emerging, then maybe you have a potential serious problem in terms of the timing of your arrival, in terms of when the insects actually come out. And the converse can be true too. If it's an extremely warm spring and the insects come out early before you arrive, well, maybe you're in trouble because all of the earlier arriving birds actually get the better territories. They produce more offspring, and then that sort of earlier arrival timing is something that – that is part of the gene pool, so to speak.

CURWOOD: With climate disruption we're seeing more climate volatility, I guess sort of in general Spring is coming earlier but there are these wide swings in Spring in a year like this one, Winter stays way too long. How are birds going to be able to adapt to that?

FARNSWORTH: One of the ways that birds can adapt to that is this thinking about is the population of individuals for a given species let's say large enough to have significant variation in the timing of arrival to where birds are going to breed. The population scale of hundreds, thousands, millions of individuals ... do you have enough variation there in that group to deal with these kinds of extremes? For some species that's certainly the case. The issue is, increasingly given all of these other kinds of insults or injuries to bird populations, in particular migrant populations, populations are declining so that variability is declining too, and when you have that kind of a situation with rapid fluctuations in climate, that's where you could potentially have real problems.

Bird feeders are helpful for migrating birds when they encounter snowy conditions (Photo: Thomas Kohler, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Looking at songbird populations in North America, how are they today compared to 20, 50 years ago?

FARNSWORTH: Populations of songbird migrants are generally quite challenged at the moment. There are some estimates out there for certain species that maybe you know 40, 50, 60, 80 percent or more of the population decline in the last several decades, and there are a number of reasons for this. Loss of habitat in North America when birds are breeding, loss of habitat in Central and South America and the Caribbean. Cats, collisions with buildings, collisions with cars and power lines and wind turbines. So, not only are these factors that are kind of responsible for mortality increasing and prevalent in many places along their journeys, but then obviously dealing with these rapid changes and in climate it sets up a really challenging scenario for migrating individuals and populations of birds that migrate.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, the Trump administration making changes to the American Migratory Bird Treaty Act, those changes are adding another hurdle for birds. Can you tell me about that?

FARNSWORTH: Yes, so this is the 100-year anniversary of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and one of the big issues now is the Trump administration basically removing a number of protections this act put in place to protect birds against some sources of mortality like open oil pits, various kinds of activities by the energy industry that in the past under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act were able to be held accountable for. So, basically there were some teeth in the Act that could allow for some sort of legal action. The Trump administration has effectively gutted the portion of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. In doing so, I think opened up these migratory populations to a potentially tremendous amount of additional hazard.

CURWOOD: So, what can people do who are concerned and want to help birds out?

Andrew Farnsworth is a research associate at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (Photo: Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

FARNSWORTH: In the case of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act you can be politically active and you can go out and vote. Even behaving locally, you can advocate to keep cats indoors, feeding birds, in particular, times like this, in the Midwest, for example, when there is so much snow left and not many insects around. There's no question that supplementing birds' food can help. There are tangible tractable things you can do every day and then there are kind of the grander human population level changes that both can happen.

CURWOOD: Andrew Farnsworth is a Research Associate at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Andrew thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

FARNSWORTH: Thank you so much for having me. Really appreciate the time.

Related links:

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- All About Birds: About the Scarlet Tanager

- The Wildlife Society: Migrating birds are getting more out of sync with the environment

[MUSIC: Trio Voronezh, “Argentine Dance” on Trio Voronezh, Angel Records 1999]

Beyond the Headlines

Hawaii is boosting government incentives for solar power while the South Carolina legislature killed a bill that would have encouraged more rooftop solar. And in Iowa, the legislature approved a measure to limit what state utilities could spend on renewable energy, making rooftop solar more expensive for homeowners. (Photo: Arlington County, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let’s turn now to Peter Dykstra, for a look Behind the Headlines. Peter’s an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. I think Peter’s on the line now from Atlanta. You there, Peter? Hello?

DYKSTRA: I’m here! And how you doing, Steve?

CURWOOD: Oh, good, and you?

DYKSTRA: I’m doing all right, and let’s talk about Hawaii. It’s an outlier, not just because it’s way offshore from the lower 48 states, but it’s an outlier because it still gets most of its electricity from the burning of fuel oil.

CURWOOD: Huh. Well, that sounds like Puerto Rico – they got most of their electricity from fuel oil – well, at least when they had electricity.

DYKSTRA: When they had electricity, right. But one of the things about fuel oil as your main power source is that it makes electric bills very volatile. When the price of oil goes up or down, the price of your electric bill goes up or down. And that spurred a huge growth in rooftop solar in Hawaii, to the point where it’s now estimated that one-third of the homes in the islands have rooftop solar.

The state of Hawaii passed legislation that adds incentives for renewable energy, including rooftop solar. Above, wind turbines climb a mountain ridge in Maui. (Photo: Kahunapule Michael Johnson, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Hm. And I imagine that number is going up?

DYKSTRA: It’s going up, and not only that, but there are other industrial-scale projects. A plan, for example, for 80,000 solar panels, a joint effort by the US Navy and the state’s biggest utility at the Pearl Harbor base. There’s also some action on the state government level. They’ve mandated that clean energy be at 100% of the state’s power generation by the year 2045, and that clean energy rewards be handed out in a system for utilities, to encourage them to get in on the action.

CURWOOD: So, it looks like solar is just going up, up, and up!

DYKSTRA: Well, in Hawaii, but maybe not elsewhere. Thousands of miles away, and maybe a universe away in terms of the way they’re thinking about the future, the South Carolina legislature killed the bill that would’ve encouraged rooftop solar. The state public utilities commission cut the price that was mandated for the state’s largest utility, to pay new large-scale solar farms, and solar farms had been a growth industry in the Carolinas. Maybe not now in South Carolina.

CURWOOD: So, it’s not such a sunny future, there, huh?

DYKSTRA: There have been efforts across the country to kneecap the solar industry from the state government level, public utilities commissions, and state legislatures in places like Kentucky, and Florida, and Nevada, and Arizona. And there’s a new one in Iowa. The state legislature in Iowa has limited what state utilities can spend on renewables, and they’ve also discouraged making rooftop solar easier and less costly.

CURWOOD: I wonder how they’ll look in history. Hey, Peter, speaking of history, what do we have this week from the history vault?

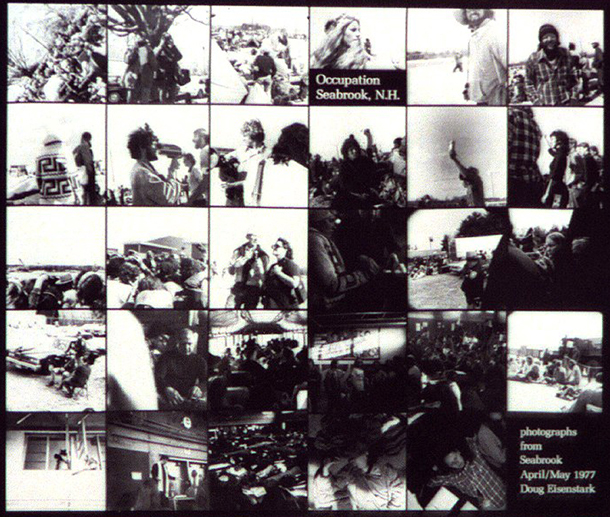

Images from the occupation by protestors of the construction of the Seabrook Nuclear Plant in 1977. (Photo: Doug Eisenstark, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

DYKSTRA: Let’s go to your neighborhood – the Seabrook Nuclear Power Station, along the New Hampshire seacoast. In 1977, this time of the year, early May, there was a huge protest at the Seabrook construction site. 1,414 people were arrested in a massive act of civil disobedience.

CURWOOD: Now, as I recall most of the charges were dropped, but a lot of people refused to raise bail, and they were held on the state tab for what, a couple of weeks?

DYKSTRA: They were held for almost a couple of weeks, the charges were dropped, but one of the two plants stuck. Two reactors were planned, one of them was abandoned for costs and controversy reasons, but the first plant was completed in 1986, and it went online in 1990.

CURWOOD: And there wouldn’t be another new nuclear power plant in this country until, what, some 25 or more years later, huh?

DYKSTRA: That’s correct.

CURWOOD: Hey, thanks, Peter! Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. And we’ll talk to you again real soon!

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot! Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- E&E News: “Hawaii upends utility model, adds incentives for solar”

- The State: “Solar resistance: SC officials again back SCE&G in fight with solar industry”

- Energy News: “Iowa governor may decide on bill to limit energy efficiency spending”

- Lane Memorial Library, Hampton, NH: “Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant”

[MUSIC: Trio Voronezh, “Gershwin Medley” on Trio Voronezh, by George Gershwin/arr.Trio Voronezh, Angel Records 1999]

Champions for Children and Corals

The 2018 Goldman Environmental Prize Recipients accept their awards. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: Today we continue our look at winners of the 2018 Goldman Environmental Prize. Last week we spoke with Liz McDaid and Makoma Lekalakala from South Africa. Other winners include Francia Márquez, who fought toxic gold mining in Colombia, LeeAnne Walters, who battled lead poisoning in Flint, Michigan and Khanh Nguy Thi who championed green energy in Vietnam. Now we turn to two more grassroots heroes who defended their environment against powerful industry. First here’s Claire Nouvian, a French marine life advocate who pushed relentlessly for a more sustainable fishing policy in the European Union. She joins us now, welcome to Living on Earth Claire!

NOUVIAN: Thank you.

CURWOOD: Now, for those who don't know, explain for us exactly why deep sea trawling is so destructive.

NOUVIAN: Well, deep sea bottom trawling is a fishing technique by which you have giant nets which are sent down to the very deep ocean and they're dragged along the sea floor and they're opened by huge doors, they’re metal doors that make sure that the net stays on the sea floor with ground rollers that take and crush much of life and they're absolutely not selective. They take and pick up anything in their wake. So, you can imagine that after deep sea bottom trawling has gone anywhere, there is pretty much nothing left.

CURWOOD: Yeah, what are some of the worst things that it does?

NOUVIAN: Well, it clear-cuts anything that's on the sea floor, and what's dramatic is that animals that live in the deep sea are really vulnerable to overexploitation. They're very slow growing. They reproduce late, very late. Later than human beings sometimes, you have to bear that in mind, right? And there are animals in the deep sea such as corals that can live thousands of years, and a single fishing net can come and destroy life that took thousands of years to grow. It makes absolutely no sense.

CURWOOD: So, by 2005, I understand that you had founded your own nonprofit organization called Bloom. What does Bloom stand for and what's the mission?

NOUVIAN: So, Bloom's logo is a little piglet squid. You really have to go check it out online. It's so cute, you would die for it.

[CURWOOD LAUGHS]

NOUVIAN: And Bloom was a name that was supposed to convey the message that the world is at a tipping point. If we do the right things, we should have very positive blooms in the ocean of nutrients that nourish life. But if you do the wrong things, if you overfish, then the blooms you get are algae, seaweed, you know, gelatinous things that will invade the ocean. And so, I thought bloom was a good tipping point name. You know, like OK, we've got a few years, we've got maybe a few decades, no more, to really fix the damage we've created, so let's see where that takes us.

CURWOOD: Now, you chose to focus on changing the fishing practices of the supermarket chain Intermarché. What did you focus on, and what was your approach?

Claire Nouvian is the 2018 European winner for her efforts to end deep-sea bottom trawling in the EU. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

NOUVIAN: Anything which has to do with fishing in Europe is decided at European level, but of course, because it's 28 member states – well soon 27 with the UK leaving the European Union, you've got a lot of member states to convince but some have more power than others, right, and so there's very important fishing nations. France is one of them, and France usually does a lot of harmful things when it comes to European decision making on fishing, and so France was completely blocking any discussion on a deep sea bottom trawl ban just because it was actually protecting its own industry which is not acceptable, right? And so we had to put a lot of, a lot of pressure on France and also on those that operate deep sea fishing.

Intermarché is a retailer, so of course, the public knows them so that was the only easy bit for us. We could just go on to campaigning right away instead of having to first establish a name. For example, Monsanto. Everybody knows Monsanto nowadays, right, but actually it's not a name that you see on the streets right? It took many years for campaigners to establish that Monsanto is a firm that is doing harmful things. So, we didn't have to go through that. That's the only thing that, at least, was easy. Everything else was difficult.

CURWOOD: So, what was your approach to Intermarché, this supermarket chain?

NOUVIAN: OK, our approach is always first try to cooperate. And so we tried that for two years with all deep sea fleets whether it be Intermarché or others. We really tried to share information. We thought, “’You know, they are ignorant. They don't know what's going on in the deep sea.”’ We need to tell them. That was a bit naive of me because I thought, you know, we need to educate them and once they're educated they will, of course, make the right decision. But of course they did not.

So, we had to become a little nastier, you know, after two years and we started to investigate their business model and that was really a really interesting bit because nobody had looked into their economic performance. And so we bought the financial accounts of all these deep sea fishing fleets and established ... we were so surprised, they were all pretty much unprofitable, despite receiving very large amounts of public money, public subsidies. So, you've got your own taxpayers' money going into feeding the destruction of the natural world. The most vulnerable marine ecosystems were destroyed because of our taxpayers' money.

CURWOOD: Now, how do France's fishing practices compare to the rest of the EU?

NOUVIAN: Well, France is is a very important fishing nation. So we are like the UK, like Spain. We've got large-scale actors that dominate the debate. They are...I don't even know what to call it. I mean is it collusion, is it complicity? I don't know what, they're so close to public authorities and all decision-making reflects the political representation of the large-scale sector. So, worldwide you'll see this is the same issue. Small-scale actors are not ideal, but they really are as close to good and sustainable as you can get, right, pretty sustainable fishing practices with very few discards. They don't need as much public money at all. These guys get trampled on.

CURWOOD: So, after an extensive campaign the led by your organization, Claire, France has now banned all deep sea trawling below a depth of 2,600 feet. That's a half a mile. How did that feel?

NOUVIAN: Well, that felt like a huge success, but it was a collective win. I have to say there is, the Pew Charitable Trusts really were very helpful, and there's a guy that really needs to be mentioned because he was my deep-sea buddy for all these years. There are two actually. There's a Professor Les Watling from the University of Hawaii who was instrumental in providing very good data and Matthew Gianni, a former commercial fisherman, American person, who just thought what we are doing to the ocean is absolutely gruesome, we should not accept that, and he came on this side of advocacy a long time ago and he made a big difference for the world's oceans. So, yes it was a collective win.

Claire at a fish market. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: So, what are your next goals for fishing reform in Europe?

NOUVIAN: OK, well, it's not just Europe. We really have an international important process right now. So, public money going into becoming a bait, like a financial incentive that really creates this overfishing problem at world scale. So, what we really need, we need all nations, which are a member of the World Trade Organization to come together and to start subsidies’ negotiations which they're doing right now.

But they have to come to a deal by 2019 because they have a year and a half where they need to sit down, agree on an international legally binding agreement that's going to make sure that harmful fisheries subsidies that fuel overfishing and overcapacity at a world scale, that needs to stop. I can only encourage media and citizens to really watch and put pressure on all governments. There will be no sustainable fishing, no way, no way ever if we still have the financial incentive. So we need to cut the bait.

CURWOOD: Excellent. Hey, before you go, Claire, how has this award affected your work? What's it meant for you at home in France and in the rest of the EU.

NOUVIAN: So, I can answer that question from a personal capacity because I can tell you what it does to me, but I don't know what it's going to do to my work arena. Will it create an impact? I have no idea. From a personal point of view, this is for me the biggest award ever. For me, it's the only one where corporate money actually really encourages true activists. There's no green-washing here. There's none of that going on. People here take risks, they name, they shame if need be. They have huge corporate enemies and still the Goldman money and the Goldman award goes to them! I mean if the financial sector were inspired by the Goldman Prize, can you imagine what it would do to the world? Imagine the financial sector, on its whole, dropped their bonuses for causes. Can you imagine it would fix the world's problems in 10 years. We would be celebrating in 10 years. So, yeah, maybe I hope that beyond just me, I hope that the corporate and financial sectors get seriously inspired by what happens and what the Goldman Environmental Prize does for people in real life.

CURWOOD: Claire Nouvian is the founder of the ocean advocacy group Bloom and one of this year's Goldman Prize winners. Claire, thanks so much for taking the time with us and again, congratulations.

NOUVIAN: Thank you very much.

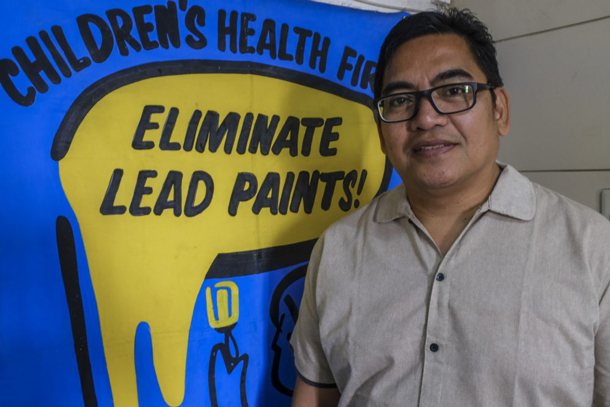

Manny Calonzo is the former director of the Ecowaste Coalition, which works to find sustainable solutions to toxic chemicals and other environmental hazards that impact local communities. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: For the Islands Nations category of the Goldman Environmental Prize, this year’s winner was Manny Calonzo, who spearheaded a campaign to eradicate lead paint from the Philippines. He also has his sights set on tackling the lead paint problem in other developing countries. He joins us now – welcome to Living on Earth Manny!

CALONZO: Hello, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, when you began this, how prevalent was lead paint in the Philippines?

CALONZO: Before we started our campaign, we had no understanding that paints being sold in the country contained high concentrations of lead. It was only after we conducted our first study that was way back in 2008 that we realized that it's a huge problem.

CURWOOD: So, what compelled you to become so involved in solving this issue?

CALONZO: In the Philippines the practice of conducting blood lead tests, especially children, is not that common, so it is very difficult to ascertain whether a child is contaminated with lead or not. Assuming all lead in paint has been banned in US since the late 70s, but in many developing countries lead in paint is still widely produced, distributed, sold and used. In the course of our work, we have read about studies and reports in US about kids being poisoned because of their exposure to lead from different sources. And I think there is no question that if lead is bad for American children, it must be bad for Filipino children as well.

CURWOOD: First, I want to understand the studies that you did with eco waste to get hard data on the scope of the lead paint issue. What did you find?

CALONZO: First, we went to the paint stores to conduct a brand survey. We determined which brands and which colors will be bought. We prepared the samples and sent the samples to the laboratory for analysis. In most cases brightly colored solvent-based paints contain high lead concentrations. This would be the yellows, the oranges, the reds and the greens. And especially before the policy was implemented, we saw high concentrations of lead content in most of these paints. We have found dangerous concentrations of lead sometimes above 10,000 to 100,000 parts per million, and when the threshold limit is only 90 parts per million. But the last study we conducted, Steve, was in 2017 and we were so relieved to find out that the percentage of paints containing high lead concentrations have significantly dropped.

CURWOOD: How were you able to persuade the paint industry to make changes?

CALONZO: Yeah, it was the result of our constructive relationship with all the stakeholders, coming from the government, the paint industry, the civil society, the health care sector and academia. With respect to the paint companies we have established a good rapport with the Philippine association of paint manufacturers. We managed to agree on several important points, and one of them is that lead has to be removed from paint formulations in order to protect children's health. I would like to add that our policy also requires the phase out of lead containing paints. We have already completed the three-year phase out period for lead containing paints use for homes, schools, daycare centers, playgrounds and the like. So, by 2020, we hope the Philippine market would be free of lead containing paints.

Because of Manny’s efforts, 85% of the paint market has been certified as lead safe in the Philippines, and schools now require lead safe paint. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: So, how is the rest of the, of the less developed world doing on the lead paint issue?

CALONZO: There is a global movement to eliminate lead in paint by 2020. The United Nations has developed this collaborative initiative in the form of the global alliance to eliminate lead in paint, which is comprised by governments, industry players, and government organizations and the like. But the movement has been has not been that fast as we have wanted. Since, 2011, a few countries have adopted lead paint regulations. I can name Sri Lanka, Nepal, India, Thailand, Philippines, and more recently Cameroon and Kenya. But we're talking here of hundreds of countries that have yet to adopt mandatory regulations that will ban lead in paint. So, there is a need for more work to be done and for paint makers as well as government regulators together with civil society to come together and agree on a policy that will protect children from lead exposure and phase out lead in paint at the soonest time possible.

CURWOOD: Manny Calonzo is the former president of Eco Waste and a 2018 Goldman Prize recipient. Congratulations, Manny. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

CALONZO: Thank you very much, Steve.

Related links:

- Our conversations with two other 2018 Goldman winners

- Claire Nouvian is the founder of the NGO Bloom

- More on Manny Calonzo and his Lead Paint Campaign

- Read about all the winners on the Goldman Prize website

[BIRDNOTE® THEME]

BirdNote®: Whooping Cranes

A Whooping Crane spreads its wings in the dewy grass. (Photo: IUCNweb CC)

CURWOOD: BirdNote today takes us to the second largest national park in the world. It’s over 17,000 square miles and is a UNESCO world heritage site. And as Michael Stein tells us it’s the summer home for America’s tallest bird.

.

BirdNote®

Wood Buffalo National Park – Birthplace of Whooping Cranes

[Calls of Whooping Cranes]

In the Canadian north, where Alberta meets The Northwest Territories, lies the huge Wood Buffalo National Park. Here the Peace and Athabasca Rivers run through fescue grasslands, boreal forests, and wetlands of international significance. Here one of the world’s most endangered birds, the Whooping Crane, comes to dance, nest, and raise its young.

[Calls of Whooping Cranes]

“I like to describe Wood Buffalo National Park as a place of superlatives,” says park superintendent Rob Kent. “Visitors can see pristine ecosystems, 5,000 bison, 150-pound wolves, the largest freshwater delta in North America, and fire and ice that shape things on a grand scale.”

[wolf howl followed by wetland]

Whooping Cranes nest in the largest freshwater delta in North America, located in Wood Buffalo National Park. (Photo: Drew Brayshaw, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

The world’s last completely wild flock of Whooping Cranes – about 275 – returns in spring to a vast mosaic of marshes and shallow ponds. In summer, with 20 hours of daylight, you can almost hear the explosive growth of plants and insects. [Insects] The insects become food for the dragonfly larvae that become food for the birds.

When summer ends and the juveniles are able to fly, the cranes fly 2,700 miles to winter on the Gulf Coast of Texas. I’m Michael Stein.

[Calls of Whooping Cranes]

###

Written by Chris Peterson with special thanks to Rob Kent, WBNP Superintendent

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Calls of Whooping Cranes [2748 and 2749] recorded by George Archibald; honeybee and other insects [60446] recorded by V.J. Ketner.

Nature SFX sounds recorded by Gordon Hempton of Quietplanet.com. #18 stream flowing, #63 coniferous forest with insects, ravens and other birds; wetland pond with morning birdsong #97

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2005-2018 Tune In to Nature.org April 2018 Narrator: Michael Stein

Reference: www.parkscanada.gc/woodbuffalo

https://www.birdnote.org/show/wood-buffalo-national-park-birthplace-whooping-cranes

CURWOOD: Dance on over to our website, loe dot org for pictures and to learn the Whooping crane two-step.

[CALLS OF WHOOPING CRANES]

Related links:

- “Wood Buffalo National Park – Birthplace of Whooping Cranes” on the BirdNote® website

- Canada’s Wood Buffalo National Park

CURWOOD: Coming up, why folks in Kerala, India, say homegrown food protects their health. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth, stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. And from a friend of Sailors for the Sea – working with Boaters to restore Ocean Health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joel Mabus, “Paper Doll-Glow Worm”]

Kerala’s Ambitious Organic Pledge

Most Kerala residents buy produce at large, open-air markets, where vegetables are typically grown using chemical fertilizers and pesticides. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Kerala could be Paradise. Tucked along the western side of the bottom tip of India, the state is always warm or hot, wet and luxuriant. Coconut palms fringe its beaches, and line its roads, crops grow year-round, and Keralans are among the best educated in the country, with a literacy rate of about 98%. It’s a traditional source of spices like cinnamon, nutmeg, pepper and cardamom, but today its biggest export is its people, who work in businesses and bureaucracies in the Middle East and remit money back home.

That cash has boosted Kerala’s financial economy, but it has also left it short of people to work the land. There is locally produced rice, but most of the food is imported and both rice and imports rely heavily on chemicals. Alarm at excess chemicals in food and rising cancer rates caused the Kerala government to pledge to go 100% organic by 2020. Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer took a trip there to check it out.

[MUSIC FROM GANESH TEMPLE IN TRIVANDRUM]

Helen Palmer visited Kerala’s capital Trivandrum during pilgrimage season. Devout Hindus travel long distances and walk barefoot in black dhothys to visit the Sri Padmanabhaswamy temple. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

PALMER: It’s pilgrimage season when I arrive in Kerala’s capital, Trivandrum. Streets are thronged with devout Hindus wearing black dhotis, the wide length of cotton cloth Indian men wear knotted round the waist. They trudge barefoot from the Central Railway station to the monumental Sri Padmanabhaswamy Temple, reputedly the richest in the world. To a visitor, it’s a reminder of the deep history and traditions still powerful in modern Kerala, which is actually dealing with a modern plague – rising rates of cancer widely blamed on pesticides and chemicals in food. Biju Prabakhar is director of Agricultural Development for Kerala.

PRABAKHAR: I was food safety commissioner of the state in 2010 to 2013 during which we have found that lots of pesticide residue are on vegetables, then antibiotics on meat and poultry. Or even some of the fish sellers or ice factory owners, they were keeping fish in formalin and ammonium sulphate and that kind of chemicals. So this was actually widely-publicized in the media that these kinds of spurious material are in our food and the medical community agreed this is one of main reasons for the cancer, because Kerala has a high incidence of cancer.

PALMER: In the three years up to 2016, cancer rates in Kerala rose over 10% faster than in most of the country, and two-thirds of cases prove fatal, due to a lack of specialized care. Biju Prabakhar says public anxiety, and the cancer link with pesticides in food, much of which is imported, is why there’s such urgency to become self-sufficient in local organic produce.

Pilgrims trade their black dhothys for plain white ones to enter the Vishnu Sri Padmanabhaswamy temple, reputedly the richest in the world with vaults full of gold and diamonds. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

PRABAKHAR: Now people are really aware about this and during last three to four years the production of vegetables has almost doubled, and we are trying to reach the target of nearly around 20 lakh, 200,000 tons of this vegetables to be produced over here – we are just short of that, 100,000. So this state is poised to convert itself to – not only vegetables, coconut, everything has to be certified without chemicals.

PALMER: Rice is the main local grain, and though Kerala traditionally grows 600 varieties, most commercial paddy fields are full of high yielding, hybrid strains grown with chemicals. Export crops – spices like black pepper, turmeric, and cardomom and commodities like rubber, coffee and coconuts, – occupy a third of the state’s agricultural land, and farmers favor them over labor intensive vegetables, partly because there’s a shortage of farm labor. That’s one result of Kerala’s low birth rate related to the high level of education, which also means there are better paying jobs to choose. And the state has other hurdles to boosting food production to meet its goal of going 100 organic by 2020. Kerala’s rice pot is a narrow, coastal plain sandwiched between the sea and the Western Ghats, thickly forested highlands in the west.

State Agricultural Development Director Biju Prabakhar is helping Kerala achieve 100% organic food by 2020. The rejection of chemicals in farming is in response to the perception that they are implicated in high rates of cancer. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

SHULAPANI: One major thing, which is needed, especially for the poor farmers, is land.

PALMER: Usha Shulapani, director of the sustainability non-profit, Thanal, says that shortage of agricultural land gets worse because fields are given as dowries when girls get married or is subdivided between the farmers’ sons – more than 92% of land holdings in the state are less than half an acre. So farms become too small to be economically viable, and since other jobs pay better, working on the land fell out of favor.

SHULAPANI: In last 10 to 20 years what is happening in Kerala is that because people were moving away from farming, most of the people who have land, they are into other occupations, so the land is lying fallow – so the people started seeing cheap land, so people with other interest come and buy.

Usha Shupalani is the Executive Director of Thanal, a non-profit organization that seeks to raise awareness about sustainability and the environment. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

PALMER: This view of land as commodity has led to speculation, and urbanization, and a real estate boom that caters to Keralans returning from abroad with cash and looking for larger houses. On top of that, says Usha, there’s a problem with the agricultural leases for landless farmers – they’re too brief.

SHULAPANI: We need a policy for leasing, where the farmers, the poor farmers need to get land on a long-term basis, for five to 10 years like that, not for one year.

PALMER: With a one-year lease farmers have little incentive to improve the quality of the soil. Agriculture Director Biju Prabakhar says there’s a plan to ensure that land doesn’t lie fallow if an absentee landlord isn’t using it.

PRABAKHAR: So absentee farmers we’ll not allow not even a single land parcel to remain without cultivation. We are formulating that kind of a law which will encourage the leasing of land to other farmers, or farmer collectives or otherwise we are planning to have some kind of a taxation on those who are idling on the land. Ultimately, land is not the property of an individual, it’s the property of the state.

PALMER: Taxing or taking over fallow land is all part of the Communist State Government’s comprehensive “Green Kerala” program that covers everything from planting vegetable gardens in schools to composting food waste to create bio-gas. To help generate more income for farmers, Green Kerala mounted an ambitious “agripreneurship fair” at the former Maharajah’s Kanakakkunnu Palace, to showcase ideas to add value to everything – from coconut fiber for shoes and handbags to root vegetables. Technical Officer Safiya Shanavas of the Central Tuber Crop Research Institute points proudly a pile of unfamiliar knobbly roots of all shapes, sizes and colors – taro, cassava, yams – and tells me there are endless ways to use them.

Kerala’s Agricultural University is responsible for providing the resources, skills, and technology required for the sustainable development of agriculture in Kerala. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

SHANAVAS: Whatever you can prepare with potato we are prepare with all tuber crops. Cassava chips we are having, sweet potato chips we are having, taro chips we are having, then we have noodles, then we have pasta.

PALMER: He tells me farmers can bring their crops to the Tuber Research Institute, which will use their fancy machines to turn them into jam and flour and snacks – cassava is gluten free, Shanavas tells me, and many of these roots are loaded with antioxidants. Indeed, that’s one thing I found most striking – every food, every spice anyone grows here seems to have some special health benefits – it fights cancer, it’s good for the heart. This focus resonates with the Indian tradition of Ayurvedic medicine – and some 30 years ago Kerala opened the world’s first Ayurvedic resort. Several stands at the fair celebrate “Jack, the wonder fruit.” It’s a massive spiky yellowish brown tree fruit – very fibrous, and versatile and very good, I’m told, for fighting diabetes.

JACK FRUIT VENDOR: From the seed we make cakes and the biscuits and from the spikes we make pickles, it’s very tasty and very spicy, OK, and we can make that wine. It’s actually banned in Kerala.

PALMER: No wine in Kerala?

VENDOR: No, there is wine, but it is illegal. From the pulp we can make juice, jams, squash a lot of things, halva.

PALMER: So jack fruit makes many many things?

VENDOR: Yes of course, around 3,000 products we can make it from jack fruit. :30

Advocates call it “Jack, the Wonder Fruit.” Jackfruit is an enormous, fibrous, versatile tree fruit that is used to make some 3,000 products, from cakes and jam to pickles and wine. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

PALMER: The palace is packed with curious Keralans keen to try free samples, and check out the displays of local fishes and biodiversity – one agriculture officer tells me it’s becoming very trendy now to be interested in growing food. But it’s no easy task to increase organic food production, and even the productivity of commercial rice is falling – partly due to problems with the soil itself.

Kerala’s earth is mostly acidic, so it needs lime. That tends to leach out with the heavy rainfall and feeding the soil properly is vital – but government subsidies don’t help the average farmer do that. Despite the ambitious long-term plans to help the switch to organic practices, the state’s yearly budgets are always squeezed. The subsidies only cover the cheapest form of nitrogen fertilizer, urea, and not the other major components of healthy soil that organic crops need, such as phosphorus and potassium. Thomas Anish Johnson is a soil survey officer who teaches at Kerala Agricultural University.

Government Soil Survey Officer Thomas Anish Johnson teaches at Kerala Agricultural University. He says crop yields are falling partly because poor farmers have difficulty improving Kerala’s acid soil and the state does not subsidize enough major nutrients. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

JOHNSON: The typical India Government subsidy is given for the major nutrients only, to the nitrogen fertilizers, that the urea is mainly subsidized and the other nutrients are being imported, so they are not given subsidy. Lime is also sometimes not given at a subsidized rate, so lime application is also not practiced mostly.

PALMER: Give me some idea of what the subsidized price for the fertilizer would be versus what has to be imported?

JOHNSON: So here the subsidized urea is given at around 5 rupees per Kg – while the other vital nutrients, that is phosphorus and potash around 20 – 25 rupees per kg – so that is 3 to 4 times the price of the urea.

PALMER: Without a thick layer of organic mulch to retain water, urea tends to make the soil MORE acidic, and not adding minerals – due to the cost -- helps create micronutrient deficiencies - lack of boron and magnesium, for example, affect crop quality and yield. Government figures show Kerala’s farmers are inefficient. More generous support could help them improve soil health, and the nutrient value of their produce, and that in turn could help public health, ultimately reducing the private and public expense of treating so many cancer cases.

There are many shrines on Trivandrum streets, and devout Hindus drape marigold garlands round those that honor Ganesha, one of the beloved Hindu deities. The elephant-headed god is known as the remover of obstacles, the patron of arts and sciences, and the ruler of intellect and wisdom. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

And Kerala’s Agricultural University is dealing with another headache that plagues farmers – a bumper crop of insects. The University’s a sprawling, leafy campus outside Thrissur, the cultural capital of Kerala, that’s dedicated to improving the state’s food, farmers’ methods and pest control.

Entomology professor Berin Pathrose, trim and bald with a moustache and glasses, tells me the state’s warm tropical climate means that harmful insects – literally – have a year-round field day. He shows off a bunch of them in a large display case in the hall outside his office.

PATHROSE: This section carries the pests of fruit crops – mango, banana, guava, jack, papaya, lychee, grapes etc etc. We have a major pest called mango stem borer –

PALMER: It’s very big – about an inch and a half!

PATHROSE: Yes more than that if you consider the length of its antennae. It can bore into the heavy trunk of mangos, it will kill the mango. In the citrus we have citrus butterflies – it's a very very good looking butterflies, then coming to the next section is the plantation crops, Kerala is known for several plantation crops – where we have coconut, cashew, coffee, areca nut, rubber, ginger etc.

PALMER: To combat all these harmful insects, Professor Pathrose specializes in bio-control agents, organic methods specific to each pest, but he tells me climate change and the insects’ ability to adapt, make it a constant cat and mouse game to keep up.

His plant pathologist colleague, Resmy Vijayaraghavan, a slim woman in a colorful sari, says the benefit of bio-control methods is that they not only build resistance in the plants, they help increase the harvest. Yet she doubts that Kerala can achieve its ambitious goals of totally organic food by 2020.

Entomology Professor Berin Pathrose specializes in bio-control agents at Kerala Agricultural University. But insects are masters at adapting to the changing tropical climate and Pathrose says it’s hard to keep pace. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

VIJAYARAGHAVAN: No actually, I wouldn’t support total organic cultivation because once the disease occurs no bio-contol agents are going to be effective. So in such cases you have to resort to chemical pesticides – so the halfway organic, halfway chemical pesticides, that is the only way out. If you go for organic cultivation, the farmers might strike with a big loss.

PALMER: She argues it’s particularly the main commercial crop, rice and spices like black pepper, nutmeg and cinnamon that need chemical treatments. But some traditional methods, such as intercropping, using locally adapted indigenous seeds and crop rotation, could help prevent infestations in the first place. Still, Kerala’s developed a whole cottage industry to make bio-control agents for the farm and home.

I drop in on the nerve center of one of the most energetic groups, headed by a cheerful determined woman in a brilliant blue and green tunic over bright green pants – who arrives on a motorbike.

[SOUND OF MOTORBIKE STOPPING]

RAJ: Helen?

PALMER: I am Helen. You are Asha Raj?

RAJ: Asha Raj.

PALMER: I am so pleased to meet you!

RAJ: Come on.

PALMER: She takes me to a Spartan, functional back room.

RAJ: I’m agricultural officer, I’m Asha Raj – my name is Asha Raj, and our Kerala government has sent me to national institute of plant health management, Hyderabad, for understanding about the various technique for on-farm production of biocontrol agents.

PALMER: Asha Raj brought that technical knowhow back from Hyderabad and now spearheads an SHG, a self-help group of women, many poor and barely educated, who make these bio-control mixtures at her office. It’s a modest, somewhat ramshackle building that doubles as a plant nursery. She says farmers might want to use fewer pesticides, but organic treatments still aren’t widely available and they cost too much, so she’s passing on what she’s learnt.

Plant pathologist Resmy Vijayaraghavan (right), with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer (left). Vijayaraghavan says biocontrol agents are crucial to build resistance in plants and increase harvests, but chemical pesticides are still vital in cases of severe insect infestation. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

RAJ: Here we are training the farmers in such a mode that they can to produce these on-farm bio-control agents in their farm itself.

PALMER: She shows me the treatments they make – some feature concentrated cow urine, which she tells me can both kill insects and improve soil. Then there are bottles of bio-repellants with garlic and neem oil for pests like thrips, fruit fly traps powered by pheromones to protect cucumbers, jars of pseudomonas and trichloderma fungi that control soil pathogens.

RAJ: shall we go upstairs?

[FOOTSTEPS ON STEPS]

PALMER: Oh I see all your seedlings there!

[FOOTSTEPS]

PALMER: There are rows and rows of pots of plants – rice, tomatoes, eggplants, and peppers on the terrace, and Asha Raj tells me they inoculate the roots with helpful fungi called VAM – vesicular arbuscular mycorrhiza – to produce a biofertilizer that helps plants take up nutrients.

PALMER: And these are rice are they?

RAJ: Yes it’s rice, because in the fibrous root system VAM, it’s very much good to grow.

PALMER: So basically, this is stuff that you grow and then you give to the farmers or sell to the farmers?

RAJ: Yeah, this is being produced by our SHG and it is supplied to the farmers in the whole Trivandrum district.

PALMER: Asha Raj says she’s already trained dozens of farmers and it’s paying off for them – their organic crops now sell for prices at least 50% higher than conventional ones. But making those higher prices the reality for every farmer is a steep hill to climb.

Agricultural Officer Asha Raj leads a group of women creating inexpensive homemade biocontrol agents, used to replace more toxic pesticides. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

Usha Shulapani of the non-profit Thanal says what financial help the government does offer needs to be firmly focused not on what’s being grown, but on the farmer.

SHULAPANI: Till now the whole policy was not farmer centric, it was crop-centric. Who needs to get the support is farmer, not the crop. We have to promote mix of cropping and also crop rotation for the farmers to become sustainable both economically and ecologically.

PALMER: Kerala’s Agriculture Director Biju Prabakhar is fine with supporting the farmers. But he says in the name of public health and their own health, people should be happy to pay higher prices for safe, nutritious food.

Above, one of the women Asha Raj has trained to produce bio-control agents: safer, organic and cheaper alternatives to industrial pesticides. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

PRABAKHAR: The farmers have to be subsidized, because they are the persons who are producing. The question is whether you’d like to pay more for foodstuffs, or whether you like to pay at least ten times in the hospital for treatment of some of the disease.

PALMER: And Usha Shulapani says another shift to make the organic goal a reality is reviving old indigenous varieties – they are more nutritious and can be a hedge against climate change – along with permaculture practices. I’m struck by how the solutions she says Kerala needs sound remarkably like the fixes organic enthusiasts recommend here in the US. Maybe in the end, since we have just one Earth, feeding and caring for the soil is the key to health and nutritious food for all of us, whether we pray to Vishnu or some other god.

[TEMPLE MUSIC, SINGING, PRECUSSION]

PALMER: For Living on Earth, I’m Helen Palmer in Trivandrum, Kerala.

Related links:

- The Government of Kerala, India

- Kerala Agricultural University

- Thanal: People, Planet, Sustainability

[MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q2ZnJiPQ3hM

Vayali Folklore Group, recorded live at the Sahaj Parab, 2015, published by Musiana]

CURWOOD: Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Jaime Kaiser, Hannah Loss, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Aynsley O’Neill, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari.

Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org – and like us, please, on our Facebook page – PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth