September 7, 2018

Air Date: September 7, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion Blocked

View the page for this story

Canada’s Federal Appeals Court has blocked the controversial Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion unless and until the Trudeau government properly consults with First Nations and studies impacts to southern resident killer whales, a process expected to push the project well past Canada’s elections in 2019. Rather than see the expansion project die for lack of private capital the Canadian government has purchased the Trans Mountain Pipeline for $4.5 billion. Host Steve Curwood spoke with reporter Laura Kane of The Canadian Press. (08:56)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells Host Steve Curwood that former Mass. Republican governor and Utah US Senate candidate Mitt Romney appears to have flipped – again – on how seriously he’s taking climate change. Then, they discuss a request by oil and gas companies in Texas for protection against sea level rise. Finally, they reflect on George H. W. Bush’s environmental legacy and the passing of Ed Marston, a founder of High Country News. (04:07)

Volunteers Test Drinking Water in Puerto Rico

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

When Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico, water utilities were shut down, making access to safe drinking water one of the most pressing issues across the island. Faced with water-borne diseases, a citizen science group in Rincón, Puerto Rico rallied to help test drinking water sources. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports. (08:09)

Crop Pests in a Warmer World

View the page for this story

Climate disruption poses significant threats to agricultural yields. Now, a new study examines how rising temperatures could lead to increased insect pest activity and dramatic crop loss. Host Steve Curwood spoke with Michelle Tigchelaar, a research associate at the University of Washington and one of the authors on the study. (07:06)

Eager: The Surprising Secret Life of Beavers

View the page for this story

The largest rodent in North America is sometimes seen as merely a pest, but a growing cohort of self-styled “beaver believers” is celebrating these toothy, dam-building creatures as a keystone species on which entire freshwater ecosystems depend. A 2018 book, Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter, takes readers up close and personal with their history, ecology and physiology. Author Ben Goldfarb spoke with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering about why some landowners are welcoming in beavers to help store water and revitalize streams in the increasingly arid American West. (17:28)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Laura Kane, Michelle Tigchelaar, Ben Goldfarb

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Bobby Bascomb

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. An appeals court has blocked the expansion of the Trans Mountain Pipeline, leaving taxpayers with the tab and roiling Canadian politics.

KANE: The government of Canada has now purchased the pipeline, so it's committed to getting this done. It believes it's in the national interest. But, we're not likely to see this redoing of the indigenous consultation and the environmental review done by the federal election in Fall 2019.

CURWOOD: Also, after Hurricane Maria most Puerto Ricans had no safe drinking water.

TOMAR: So you immediately had to resort to whatever your closest source of natural, what we call informal, source of water were: springs, wells or streams. For the vast majority of the island that was it and just hope for the best.

CURWOOD: Citizen scientists jumped into the breach. That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion Blocked

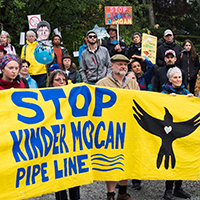

Protestors gather for a March to Stop Trans Mountain Oil Pipeline at the Kwekwexnewtxw Watch House and the Kinder Morgan Tank Farm in Burnaby, British Columbia in August 2018. The pipeline has been heavily protested by First Nations groups and their allies. (Photo: Sally T. Buck, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

For years activists have fought the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion Project in western Canada, a move that would triple the amount of carbon heavy oil sands crude it could carry. In recent months indigenous groups and their allies intensified their demonstrations, chanting, singing, and chaining themselves to a key entrance, as they faced arrest in droves. Pipeline owner Kinder Morgan finally yielded to the protests and moved to cancel the project. But then the Trudeau Administration stepped in to buy the pipeline for $4.5 billion Canadian dollars, vowing to move ahead with the expansion in the name of “the national interest” of creating jobs and boosting the economy. Now the Federal Court of Appeals has blocked construction, ruling that the Canadian government cut corners in its review of project plans. Reporter and editor Laura Kane writes about the pipeline for The Canadian Press. Welcome to Living on Earth!

KANE: Thank you so much for having me, Steve. I'm happy to be here.

CURWOOD: What are we talking about in terms of capacity? How important is this to the folks who are in the oil sands business?

KANE: It's very important to the industry, particularly in Alberta's oil sands which has been hit hard by lowering oil prices where a lot of workers have lost their jobs and been laid off in recent years. This project was really seen as a way to get some of those workers up and moving. It was also seen as a way to get more oil from Alberta's oil sands to tidewater, so that it could be shipped overseas to Asian markets. Currently a lot of Canadian oil is going to the US, and Canadian industry folk and political leaders argue that we're not getting as good a price as we could be with Asian markets that we are from American. And so this project was seen as crucial to get the oil to tidewater. It would expand the capacity of the pipeline threefold. So, it would go to about 890,000 barrels of oil a day from Alberta's oil sands and it would increase the number of tankers leaving Metro Vancouver’s port sevenfold. So, that goes from five per month to 34 tankers per month. So, it is a massive resource project that the government has really really wanted to get off the ground, that industry people have really wanted to get off the ground, but that environmental leaders and First Nations leaders in British Columbia have been very much opposed to.

CURWOOD: So, how significant is this court decision?

KANE: It is a game changer in terms of the likelihood of this project getting off the ground anytime soon. It found two fatal flaws in the government's review of the pipeline, which by the way has been going on for years. I mean, this pipeline was first proposed in 2012, it was approved by the government in late 2016, and now we're in 2018. So, this is a very extensive process that has now been sent back to the review phase.

The National Energy board must now consider the impacts of increased tanker traffic from the pipeline on the marine environment, especially the effects on endangered Southern Resident killer whales. (Photo: NOAA Fisheries West Coast, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, how much could the project be delayed by this court decision?

KANE: It could be delayed for years. The court ruling found that the government needs to go back and it needs to review the marine shipping effects, so the effects of the increased tanker traffic on the marine environment. We have a very endangered southern resident killer whale population off the coast of BC and Washington State, where there are only 75 of these whales left and the reproductive potential is quite low, so environmental leaders argue that this project would have a significant impact on these whales. So, going back, having to reopen the National Energy Board review and look at how it would impact the marine environment and the whales -- it's going to possibly require some changes to the design of the pipeline itself and the shipping route in order to avoid impact on the whales. So, that process could take a very long time.

CURWOOD: And what about the other part of their decision, I gather it involves First Nations, indigenous folks.

KANE: That's right. So, the very final phase of indigenous consultation was found to be flawed. The court said that the government essentially sent note takers to go out to the first nations that were opposed to the pipeline, record their concerns, take them back to the government. But they didn't do anything about those concerns. And they're pretty significant and specific concerns that could be addressed if the government was willing to do so. So, for example, there's a First Nation in central BC whose aquifer, its main source of drinking water, is crossed by the pipeline. So, they're very concerned about what could happen to their drinking water if something goes wrong with the pipeline. This is a concern that the government could have addressed and the court says should have addressed, but didn't. So now they need to redo all that consultation with all of the indigenous groups along the pipeline route and really do it in a meaningful way where they listen to the concerns and provide accommodations where necessary. So, that process could take a very long time.

CURWOOD: So, what is Prime Minister Justin Trudeau now saying about this decision and the way forward?

KANE: So, he has said that he's committed to building the pipeline project, that he wants to move forward in the right way, which is what suggests to me that he is going to follow the court's orders on this and redo the indigenous consultation and the part of the review that requires them to look at marine tanker traffic. It seems like he's trying to put on sort of um -- a brave face in light of how devastating this decision really is to the pipeline project. He's trying to reassure Canadians that the government's committed to this project moving forward, but he's in a very difficult spot. He partnered with the government of Alberta on this and the government of Alberta is furious that this project isn't moving ahead.

Following the Canadian federal appeals court ruling to strike down the approval of the Trans Mountain Pipeline, Alberta Premier Rachel Notley said the province will withdraw from the federal climate plan until Prime Minister Justin Trudeau can get the project back on track. (Photo: Premier of Alberta, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: What are the chances that this pipeline will eventually get built? I mean, you say there’s delays, probably another couple of years.

KANE: If it were a private company operating this pipeline, I think a lot of experts would say it's dead, it's over, it's not going to happen. In fact, Kinder Morgan wanted to walk away months ago because of that concern, but the government of Canada has now purchased the pipeline so it's committed to getting this done. It believes it's in the national interest. But we're not likely to see this process actually completed, this redoing of the indigenous consultation and the environmental review, done by the federal election in fall 2019, and who knows what the price of oil is going to be in 2020, 2022. I don't know how the government gets out of building it eventually, when they have purchased it for $4.5 billion dollars, not including construction costs. They're determined to see it done. It's going to hinge on who wins the next federal election, what the environment looks like in 2022, and if they're willing to kind of bulldoze through protests that are likely to continue for years to come.

CURWOOD: So, the elections are coming up. How does this decision affect what could happen with the elections?

KANE: I mean I think it could really hurt him. The Liberal government won in 2015 on a wave of actually indigenous voters, of people in British Columbia in particular who were willing to vote Liberal because he made a lot of promises around Indigenous reconciliation and environmentalism. So, I think a lot of people who voted Liberal in the last election have been very disappointed with his government's purchase of this pipeline and its failure to consult First Nations adequately on the pipeline. That said, are there people who are more conservative leaning who might be willing to vote Liberal? It's hard to say. We also have a conservative party in Canada that's more on the right of him. So, the Liberal Party in Canada is typically the centrist party. So, you really do need to gather people from both sides, and I don't see him being able to do that from the left.

CURWOOD: By the way, if this pipeline were to be expanded, to triple the sale of these oil sands into the world market, what does that do to Canada's commitment under the Paris Accord?

KANE: I don't see how they can meet it. They have said that their carbon pricing plan will offset, so they're trying to get carbon pricing in all provinces, but provinces have started to back away from the agreement. In fact, Alberta -- just last week after the court decision came down -- said we're not going to agree to a tax on carbon until you get this pipeline built. So, it looks like that plan is falling apart. The government continually says that they're trying to grow the economy while protecting the environment. But the reality is, if this pipeline project were to proceed, I think most experts agree that we could not meet our commitments under the Paris Agreement.

Laura Kane is a reporter and editor for The Canadian Press. (Photo: Laura Kane)

CURWOOD: To what extent are the First Nations people who had opposed this Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion celebrating this decision?

KANE: Certainly on the day the decision came down the indigenous groups who fought the project were so joyful. It was a really powerful moment. They stood on the banks of Burrard Inlet, which stands to see you know tanker traffic increase sevenfold if the project proceeds, and they said we're winning. And we fought this for all Canadians, we fought this for the world. We could have negotiated millions for support of this project and instead we protected the land and the water for you. So, that was certainly the mood last week and we'll just have to wait and see whether the project does in fact proceed at some point in the future.

CURWOOD: Laura Kane is an editor and reporter with The Canadian Press. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Laura.

KANE: Thank you so much for having me. I appreciate it.

Related links:

- The Star | “Trans Mountain expansion could be delayed for years by court decision: experts”

- From the LOE archives: “A Pipeline Eco Engineer Protests”

- Listen to another LOE interview: “Canada Buys Tar Sands Oil Pipeline”

- Global News | “Timeline: Key dates in the history of the Trans Mountain pipeline”

[MUSIC: Kavita Shah, “Little Green”]

Beyond the Headlines

Mitt Romney and his wife Ann at a recent rally in Orem, Utah. (Photo: Ben PL, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well it’s time now to take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter’s with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and DailyClimate.org. He’s on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia, where -- well, hey, we may be headed into fall but it sure feels like summer here.

DYKSTRA: Yeah here too, we’re still in the high 80s. But I want to start talking about your former Governor up there in Massachusetts, none other than Mitt Romney. In the early 2000s when he was Massachusetts Governor, he had one of the most forwarding-thinking climate actions plans of any of the 50 states. That’s a Republican, all over climate change! Not only calling for action but taking big steps on it. And then he ran for president and a funny thing happened.

CURWOOD: Hmm, he got a bit of amnesia you’re saying about climate change?

DYKSTRA: He did, and not only did he make fun of Barack Obama for talking about climate change, but Romney was expressing some serious doubts about it himself. Fast-forward to right now, 2018, Mitt’s back in Utah running for the Senate there and all of a sudden he’s talking climate change again in the face of huge wildfires, not only in Utah, but throughout the American West.

CURWOOD: So I guess there can be some situational ethics. What else do you have for us?

DYKSTRA: Well, big oil down in Texas is forwarding an unusual request via the state of Texas, who’s asked for 12 billion dollars in Federal aid for seawalls, floodgates, and other things to help protect oil refineries and petrochemical factories, and other oil facilities along the Texas coastline from the Louisiana border down to the Houston ship channel.

The Houston Ship Channel is a busy seaport lined with oil and natural gas infrastructure. (Photo: Ken Lund, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So I gather they’re worried about the storms and rising seas. I think the hurricane last year in Houston makes that pretty obvious there’s a risk. But Peter, wait a second, aren’t the oil companies putting out, helping us put out all that C02 that leads to climate disruption?

DYKSTRA: Yeah the oil companies are helping to make more intense storms and make higher seas through climate change, and now they want to be protected from something they themselves helped create.

CURWOOD: And they want the taxpayers to pay for it?

DYKSTRA: Now that’s irony!

CURWOOD: So hey, what do you have from the history vault this week?

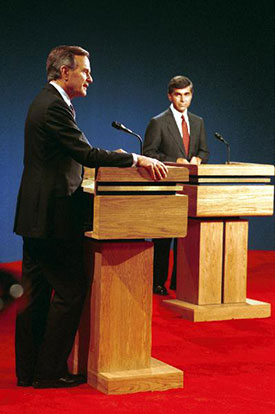

DYKSTRA: 30 years ago -- and it’s really hard to believe this was 30 years ago -- but on September 1st, 1988, George H. W. Bush, then Vice President and running against another Massachusetts Governor, Michael Dukakis, went after Dukakis because Boston Harbor was one of the most notoriously polluted places in the country.

CURWOOD: Oh yeah, you’ve got to love that dirty water, right?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, “Love That Dirty Water” is a theme song for Boston sports teams these days, but back then it was much more of a reality. Today we have headlines in recent weeks that there are humpback whales cavorting in Boston Harbor; that wasn’t the case in 1988, it really was dirty, and the Republican candidate, George H W. Bush, promised the nation he would be the environmental president. Let me repeat that -- the Republican candidate promised he’d be the environmental President.

CURWOOD: Well after all, he did go ahead and sign what would become the architecture for the Kyoto Protocol and I think the Clean Air Act as well.

Former President George H. W. Bush debates with Democratic Candidate Michael Dukakis in Los Angeles in October, 1988. (Photo: George Bush Presidential Library and Museum, public domain)

DYKSTRA: Yeah, strengthened the Clean Air Act, of course the Kyoto Protocol didn’t go anywhere as far as the United States was concerned, but if you compare papa Bush to the two most recent Republican presidents, his son George W. Bush and of course President Donald Trump, it was far from the hostility that we see today toward environmental laws and environmental regulations.

CURWOOD: Okay thanks Peter.

DYKSTRA: Well Steve, I’ve got one more note for you. Ed Marston, publisher of High Country News, passed away from last week from complications from West Nile disease, it’s a little bit of an unfortunate irony. But Ed and his wife Betsy helped grow High Country News into a must-read publication on the Western environment.

CURWOOD: And some call it the New Yorker for folks who live about 7,000 feet.

DYKSTRA: That’s sure what I call it!

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and DailyClimate.org. Thanks so much Peter.

DYKSTRA: Alright, thanks Steve, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Salt Lake Tribune | “Mitt Romney says that he’s a believer in climate change…”

- AP News | “Big oil asks government to protect it from climate change”

- High Country News | “Ed Marston, former publisher of High Country News, dies at 78”

- NYTimes | “Bush, in Enemy Waters, Says Rival Hindered Cleanup of Boston Harbor”

[MUSIC: The Standells, “Dirty Water” on Dirty Water, by Ed Cobb, Tower Records]

CURWOOD: Just ahead – How a warmer world means more insect trouble for farmers.

Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[MUSIC: Adrian Legg, “Mrs. Crowe’s Blue Waltz” on Wine, Women, & Waltz, Lativity Records]

Volunteers Test Drinking Water in Puerto Rico

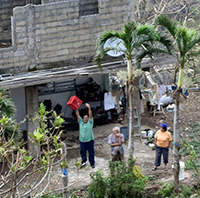

In 2017 Hurricane Maria knocked out so many trees and powerlines so that roads were blocked and supplies had to be air lifted into remote communities like this one near Utuado, Puerto Rico. (Photo: Coast Guard News, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. When the catastrophic Hurricane Maria made landfall on Puerto Rico in 2017 it knocked down trees and power lines, leaving roads impassable and communities isolated for weeks and months. Some remote communities in the mountains had to have supplies air lifted in to them by helicopter. Even towns in popular tourist areas found themselves cut off from the outside world and struggling to meet their most basic needs. Today we continue our series of stories from Puerto Rico with a report about how safe drinking water became one of the most immediate and pressing issues across the island, and also an important teachable moment. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb has our story.

[MARKET SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Rincón sits on the west coast of Puerto Rico. It’s a mecca for surfers and beach going tourists. The town has a quaint square with gourmet coffee shops and a lovely farmer’s market.

[MARKET SOUNDS]

CARLO: Cómo estás? Wow…

BASCOMB: Sonia Carlo has a farm stand at the market where she sells some salad greens, kale, and pineapple. She was on the farm with her husband and 3 children when hurricane Maria struck. She says one of the biggest challenges was just providing the essentials for her children during and after the storm.

CARLO: And you know, they were just so scared that they weren’t going to be able to drink water. You know, it's hard to tell a three year old “don’t drink all the water, we're going to run out” or “don't eat too much food”. Yeah…

BASCOMB: But when their bottled water ran out she found an alternative the kids liked even better.

CARLO: I had no choice but to give them soda. So they're -- you know they're innocent they said, “We like the hurricane! Mommy’s giving me soda and sweets!” Because, you know we had no choice, it was between letting them go thirsty or giving them, you know, soda, and which, they never tried soda before. So…

BASCOMB: Eventually the soda also ran out, and Rincón didn’t get reliable drinking water for several months. In that time the incidence of water borne disease increased greatly. There was a sharp rise in gastrointestinal issues, scabies, and leptospirosis, a bacterial infection caused by fresh water contaminated with rat urine.

TOMAR: It really put into focus this water quality issue.

BASCOMB: Steve Tomar is originally from Florida but he’s been living in Rincón for more than 40 years. He’s tall and lanky with long brown hair and a gray beard. He says getting drinking water was a problem for everyone after the hurricane.

Steve Tomar stands in front of Rincón’s only source of drinking water after Hurricane Maria. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

TOMAR: There’s no water authority water and the stores are closed because they don’t have generators. Or if they do have generators they sold out of water days ago. And you knew that was going to be like that for months. So, you immediately had to resort to whatever your closest source of natural, what we call informal, sources of water were… springs, wells or streams.

BASCOMB: So, you come down here, you dip your cup in the stream and hope for the best.

TOMAR: Yeah, that was literally, for the vast majority of the island, that was it. Just hope for the best.

BASCOMB: And that presented a whole host of other problems. No one had any idea if water from those streams and springs was safe or not. But that was a problem Steve could work on. He’s vice chairman of the Rincón chapter of the Surfrider Foundation and director of the Blue Water Task Force, which tests ocean water quality near the beaches.

TOMAR: So, immediately after the storm people were going hey, can you do something about checking the wells and springs and stuff? And we said, well, we’re not set up for it but yeah, yeah we can do this. Within 3 weeks we could get up and running after the hurricane, as opposed to the government agencies – it was like 3 months at the earliest before they started responding.

BASCOMB: The only tests they had on hand were for enterococcus, a hardy bacteria that can survive in a marine environment, so that’s what they began testing for. After they were able to get the right supplies, they began testing the water for other, more likely, contaminants, including bacteria from fecal matter.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: I met Steve at a park near a small stream. Little bubbles from an underground spring pop up every few seconds.

TOMAR: This literally after the hurricane was where everybody that lived in downtown Rincón had to come for their water. This was the only source they had.

BASCOMB: So, Steve and his team began their testing here and quickly branched out to include much of the surrounding area. They gave an expedited training course to Boy Scout groups and anyone interested in learning how to do water quality testing. Within a few months they tested most of the informal water sources within a 6 hour radius. After 6 hours a sample can no longer be accurately tested.

Today, Steve is testing this stream again. He repeats sampling every few weeks to monitor the bacteria count to be prepared for the next hurricane. He takes out a sterile 100 milliliter collection bag.

TOMAR: We very carefully remove the perforated top. And you do not throw your plastic into the environment. No, we have that problem already.

BASCOMB: He holds the bag by a yellow handle and dips it into the stream. Then he takes the sample to a bench under a shady tree.

Supplies for initial water testing at the spring. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

TOMAR: Here we are with our temporary lab set up at the site.

BASCOMB: He tests for ph, temperature, nitrates, chlorine and sediments and writes down the results on a data sheet. Then he’ll take the sample back to his lab in the Surfrider office and test for the things that can really make people sick, including coliform, enterococcus bacteria, and e-coli. This particular stream has levels of enterococcus at twice the federal standard, enough to close a beach if this were a marine sample. But after the hurricane it was drinking water so Steve’s team put up signs to notify people.

TOMAR: We had color-coded green, yellow and red signs. Boil for a minute, boil for 5 minutes, and boil for 20 minutes -- and quite frankly I wouldn’t be drinking it in the first place because if you’re finding that much bacteria you’re probably also going to have a lot of other, a whole suite of other problems that you wouldn’t want to use for potable water.

BASCOMB: Steve says in the past they were reluctant to take on testing drinking water.

TOMAR: Because of course you’re stepping on all sorts of toes with various government agencies and the public health services, and blah blah blah…. After the hurricane that became a moot issue. And it was just like of course you do it, because this is the community. These are your people so whatever you can do to keep them healthy and informed, you do it.

BASCOMB: Surfrider’s Blue Water Task Force to test ocean water quality is the largest citizen scientist program in Puerto Rico. And Steve says it was relatively easy to transition the skills volunteers developed for testing ocean water into testing drinking water. But he sees value in that beyond just water safety.

TOMAR: In a lot of ways I think the major benefit of these community based science programs is developing skill sets in the community. An educated populace is of course a populace that’s better able to take care of their own resources.

BASCOMB: Thay-Ling Perez is an intern with Surfrider and local to the area. She says that if there’s any silver lining here it’s the sense of community that came out of working together to get through the hurricane.

PEREZ: You also saw a lot of togetherness and community. People got to know their neighbors, which was a big deal here because a lot of people didn’t know their neighbors, they lived isolated in their world. So it’s still something beautiful that came out of it but it was also from a lot of pain.

BASCOMB: As climate change continues to warm the oceans and create optimal hurricane conditions, big devastating storms like Maria are likely to become more common in the future. Puerto Ricans have painfully learned that the government was not able to quickly respond after a hurricane, so they’re looking to each other instead. And across the island, Puerto Ricans are learning the skills they’ll need to ride out the storm together.

For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in Rincón, Puerto Rico.

Related link:

Rincón, Puerto Rico chapter of the Surfrider Foundation

[MUSIC: Natalie Merchant, “Carnival” on Tigerlilly, Elektra Entertainment Group]

Crop Pests in a Warmer World

A study published in the journal Science found that crop loss to insects is likely to increase with rising temperatures, which will make insects hungrier. Above, a maize weevil munches on an ear of corn. (Photo: US Department of Agriculture, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Climate disruption can be tough on agriculture. Research shows rising temperatures can reduce nutrient quality in staple grains and more droughts and flood can reduce yields. And now scientists are telling us global warming will also bug farmers… literally.

[SOUNDS OF INSECTS BUZZING]

CURWOOD: More heat in temperate zones means more insect pest activity and consequent crop loss. A team at the University of Washington has done the math and team member and research associate Michelle Tigchelaar joins us now to explain.

Welcome back to Living on Earth!

TIGCHELAAR: Thanks for having me again.

CURWOOD: So, what is it about climate disruption that's going to lead to more insect-caused crop loss?

TIGCHELAAR: There are really two components to why we will expect more insects in a warmer climate. The first one is that insects are ectotherms, so that means that as the global temperature raises their body temperatures rise and so they will eat more -- essentially their energy use goes up. And the second component is that as temperatures rise, more insects will survive through the winter and they will reproduce at faster rates. So we get more insects and they will be eating more.

CURWOOD: So, when this insect boom happens, which crops are most at risk?

TIGCHELAAR: All crops globally are affected by pest losses, but the ones that in terms of volume will be most impacted are our main staple crops, so corn, wheat, soy and especially wheat will see larger crop losses mostly because wheat is grown in temperate climates, and that's where we see the largest rises in numbers of insects.

CURWOOD: So, give me a number here please; how much warming leads to how much loss, roughly?

TIGCHELAAR: So, for wheat in particular we saw that two degrees of global warming - which is what we're aiming for with the Paris Agreement but are currently not yet on target for -- with two degrees of global warming we are expecting that in the mid-latitudes where wheat is grown, about 50 to 100 percent increase in how much is lost due to pests; what is currently lost is getting doubled. Our projections show that those crop losses could be in the order of several hundred million tons. But what I also want to emphasize is that these changes in insect pressure are going to happen alongside other climate change impacts on crops. So, this is on top of losses due to warming alone.

CURWOOD: So, the crops don't grow as well when it gets hot, and there are going to be more insects as it gets hotter. Sounds like a nightmare.

Increasing crop loss to hungry insects may encourage farmers to use more pesticides. (Photo: Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

TIGCHELAAR: It does, and on top of that our global population is growing and people are eating more and more Western diets which require more resources to grow. So we're kind of heading towards a crisis here where we need more food, but things being as they are, would be able to grow less of them.

CURWOOD: So, how important around the world would this loss be?

TIGCHELAAR: Combined with the other impacts of climate change on food production these impacts are tremendously important, especially for the more than four billion people on this planet who actually depend critically on staple crops for their sustenance, and households that spend the majority of their income on food, will be extremely vulnerable to price shifts.

CURWOOD: So, this could be a life-threatening issue for many people all over the world. How can we prevent or at least mitigate this massive crop loss?

TIGCHELAAR: Well, the first and foremost thing that we should do it is limit climate change as a whole, and there are several exciting and promising moves in that direction -- either through government intervention or clean energy innovation. But secondly there are also things that farmers and farm policy specialists could be thinking about, especially in the realm of pest management strategies and investments in crop developments, for crops that are more resilient against heat and pests.

CURWOOD: I imagine some would suggest genetically modified crops, so they are insect resistant. And you would say?

TIGCHELAAR: I would say that breeding strategies are going to be a really important part of a solution to climate change, but they're not going to be able to get us there alone. For instance, in terms of breeding for heat resistance, crop scientists have been trying this for several decades with little to no avail. So, that means that also farming practices and perhaps what we eat are going to have to change.

CURWOOD: Now, what about pesticides -- I mean if there are more insects that are trying to eat crops, I would think that farmers are going to roll out the chemicals to try to take out those pests.

TIGCHELAAR: Yes, also that. I am personally not an expert in the field of pesticide usage, but that seems like a logical outcome of an increase in the number of pests which is really concerning giving the detrimental effects of pesticides on the environment.

CURWOOD: How surprised were you by these results?

TIGCHELAAR: I was personally not necessarily surprised. I think our findings make intuitive and scientific sense in the sense that we understand that insects behave this way and are sensitive in this way to higher temperatures and warmth. The unique part of the study was that this was the first time we really quantified how big these impacts could be. And what's surprising about these results was that this is not an insignificant contribution to future crop losses. It is not going to be the dominant factor of how climate impacts crops, but it is not insignificant and will definitely aggravate the problem.

CURWOOD: So, you're saying that we're more likely to see the warming actually making it harder for the crops to grow as opposed to being attacked by more pests.

TIGCHELAAR: There's been a lot of work that already looks at just direct impact of heat on crop losses and together with some of the co-authors on this paper we published findings along those lines earlier this year, too, especially looking at corn, and we find there that two degrees of warming could lead to 20 percent reduction in crop yields. So, in that sense the pest component is smaller but not insignificant and will add to this problem.

Michelle Tigchelaar Ph.D. is a research associate at the University of Washington. (Photo: Courtesy of Michelle Tigchelaar)

CURWOOD: Tell me how much good news is there from this research, if any?

TIGCHELAAR: This may be a little bit speculative, but I think that the good news here is that a lot of these projected impacts are really interconnected, right, between how our society operates and our food is grown. And solving climate change and solving pest impacts and solving sort of the food crises that we're facing here in the United States might have common solutions around better land management practices, better public health policies, and if this kind of work can galvanize those kind of changes that would be a really positive impact.

CURWOOD: Michelle Tigchelaar is a research associate at the University of Washington and co-author of this paper on the projected impact of insects as the climate warms. Thanks so much for taking the time to talk with us today, Michele.

TIGCHELAAR: Thanks for your interest in our work.

Related links:

- New York Times | “The Bugs Are Coming, and They’ll Want More of Our Food”

- Science Magazine | “Increase in crop losses to insect pests in a warming climate”

- Listen to our previous LOE interview with Michele Tigchelaar

[MUSIC: Natalie Merchant, “Carnival” on Tigerlilly, Elektra Entertainment Group]

CURWOOD: Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line anytime at 617-287-4121. That's 617-287-4121. Our e-mail address is comments at loe dot org. - comments at loe dot org. And visit our web page at loe dot org. That's loe dot org.

Coming up – How some see the largest rodent in North America as an eager landscape architect and environmental hero. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth – keep listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at race to nine billion dot com. That’s race to nine billion dot com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[MUSIC: Adrian Legg, “Norah Handley’s Waltz” on Wine, Women & Waltz, Lativity Records]

Eager: The Surprising Secret Life of Beavers

Before Europeans showed up in North America, as many as 400 million beavers swam its streams. (Photo: Sandy Brown Jensen, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

We may be living in the Age of the Anthropocene, but we’re not the only creatures with impressive engineering skills. One stick at a time, beavers build dams and lodges, to hold back stream water and create safe havens from predators. All that dam-building can help scores of other creatures in the process, providing more habitat for fish, birds, insects, amphibians and even moose. Ben Goldfarb is a journalist and author of the book Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter, and he spoke with Living on Earth's Jenni Doering.

DOERING: So, Ben the first hit when I Googled your name was your website with the heading, your name -- Ben Goldfarb – “Environmental Journalist, Beaver Believer”.

GOLDFARB: [LAUGHS]

DOERING: So what does it mean to be a Beaver Believer?

GOLDFARB: Yes, so the Beaver Believers are this tribe of scientists and land managers and farmers and ranchers, really anyone who believes that restoring these little incredible ecosystem engineers -- the beaver, the North American beaver -- can help us deal with all kinds of environmental problems, that by building their dams and creating ponds and wetlands they help us store water for farms and ranches; they help filter out water pollution, improving water quality; they create habitat for the fish and wildlife that we care about. They slow down floods, they act as fire breaks, they provide all of these really valuable services for us. So, the Beaver Believers are people like me who have come to recognize that this is an incredibly important animal that we should cooperate with in landscape restoration.

A beaver dam in the Yukon Delta. These painstakingly built structures, which the rodents build to create a suitable habitat, act as “speed bumps”, slowing water down and connecting a stream with its floodplain. (Photo: Alaska Region U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: So, what convinced you to convert to this beaver belief?

GOLDFARB: [LAUGHS] I think like most people who love being in the outdoors, I had certainly been around beavers a fair amount. I was somewhat beaver savvy, but I didn't become a true Beaver Believer until a few years back, I was living in Washington and I met this guy named Kent Woodruff who was the director then of this group called the Methow Beaver Project in the Methow Valley in central Washington. And basically what the Methow project does is they live trap nuisance beavers, beavers that are clogging up road culverts or cutting down people's apple trees or flooding fields or what have you. And they relocate those beavers to high up in the headwaters of the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest in central Washington, where beavers can build dams away from people and keep water on the landscape in central Washington, which is this really this pretty dry place. So, it was being out there with Kent, this very skilled naturalist and was really good at interpreting for me just how profoundly beavers were changing this landscape. It was that experience that sort of awoke me to the incredible landscape-changing power of this rodent.

DOERING: Yeah, in the passage where you talk about Kent Woodruff and the Methow Beaver Project, you talk about this little love story between two beavers, Sandy and Chomper. What's their story?

Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter is Ben Goldfarb’s first book. (Image: courtesy of Chelsea Green Publishing)

GOLDFARB: Right. So, one of the challenges of beaver relocation is that ideally you want to move entire beaver families together, right? Beavers are these very family-oriented animals. They mate for life, and if you move one beaver by itself, you know, that beaver is just going to go wandering around looking for a partner and it's probably going to get eaten by a bear or a cougar or a coyote.

DOERING: Oh no!

GOLDFARB: [LAUGHS] Yeah, that's pretty sad. And predation is one of the biggest obstacles to beaver relocation in many parts of the American West. So, ideally you can move compatible beaver couples together, that way when you relocate them, they will immediately settle down, build a dam, create a lodge, and be safe from predators and start doing the valuable work that we want them to do. So, what the Methow Beaver Project does is they basically operate this sort of rodent love motel, kind of a beaver Tinder, where they match up males and females and create compatible couples, ideally, that they can move together. So, when I visited Kent and the Methow Beaver Project, Sandy and Chomper were these two beavers who had successfully been paired up in one of the little concrete huts that they build for them, and those two beavers were successfully relocated together.

DOERING: A happy ending to that love story.

GOLDFARB: Yeah, hopefully, they're still out there doing their thing. [LAUGHS]

DOERING: [LAUGHS]

GOLDFARB: I probably should go visit them some time.

“Half-Tail Dale” awaits a mate at the Methow Beaver Project’s rodent love motel. (Photo: Ben Goldfarb)

DOERING: Well, one of things you write about in your book, Ben, is how difficult it is to tell which is the male and which is the female.

GOLDFARB: Right, yeah, beavers make things pretty difficult. So, beavers as you can understand, male beavers don't have external genitalia, right? I mean, if you're an animal that spends its life sort of swimming around logjams, you don't want too many dangling appendages that you can get snagged on things, right? So, male beavers keep it nice and tucked up which means that unless the female is lactating, there's really no way to look at a beaver and determine whether it's a male or female. So, which of course makes paring up compatible beaver couples pretty difficult, right? So, the only way you can really reliably tell without doing a DNA test is actually by smelling the beaver. So, beavers are these very scent-oriented animals and they have these couple of different sets of scent secreting glands. And basically what you do is you have to express one of these scent glands with your fingers. You kind of push on the belly until the little gland, this little mound of pink flesh pops up, and then you squeeze out a dollop of this scent secretion, and if it smells like motor oil it's a male beaver, and if it smells like cheese it's a female beaver. When I sniffed beavers with those guys, I wasn't really able to differentiate very reliably, but if you're if you're an experienced beaver sexer, you can tell males from females with pretty much 100 percent accuracy.

DOERING: Wow. Well, it sounds like a very messy job.

GOLDFARB: Yes, definitely. I think one guidebook says that you should always do this process with goggles on and your mouth closed.

The telltale tooth marks of a beaver gnawing on a felled birch tree. (Photo: Travis, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: [LAUGHS] Oh my. It's very fun to talk about beavers. I think a lot of us understand they have big teeth, they have a big flat tail. What are some of their other amazing traits that they have?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, beavers are just so well adapted to this really unique semi-aquatic niche they occupy. They have these transparent second set of eyelids that they can close over their eyes that basically act as goggles when they're underwater. They have a second set of fur-lined lips they can close behind their teeth so they can chew and drag sticks underwater without drowning. Of course, the beaver’s tail is this amazing appendage. It kind of acts as a rudder while they're swimming, it's also a fat storage device, they actually put on fat for the winter in their tails and it acts as this sort of this thermo regulatory exchange system as well. The tail actually heats and cools them or helps regulate their body temperature. So they're just incredibly well adapted to this very unique lifestyle they have. Beavers actually have as many individual hairs on a single patch of skin the size of a postage stamp as we have in our entire head, so amazingly dense fur and, of course, that's part of what led to their downfall. You know, their fur made -- and still makes, in some places -- incredible hats, but in the end it was ultimately their demise.

DOERING: That's right. I mean, you talk about this story of how humans, white humans mostly, almost eradicated the beaver in North America. What exactly happened a couple of centuries ago when white people realized North America was just full of beavers?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, you know the first European fur traders and trappers showed up in the early 1600s and just set about trapping out beavers from every single stream, river, lake and pond they encountered. I mean, along with timber and cod that was really the most important natural resource in the new world were these amazing beaver pelts. When the first colonists arrived and the pilgrims showed up, they owed lots of money to their creditors back in Europe and the only way they could repay those debts was by shipping beaver pelts back across the Atlantic. So beavers made the Massachusetts Bay Colony possible from one standpoint. So, when Europeans first showed up there were as many as 400 million beavers in North America and by the year 1900, after three centuries of unabated trapping, their population was probably down to around 100,000 in all of North America, so just to a catastrophic collapse. Once we trapped out beavers all of those dams broke down and all of those ponds and wetlands basically drained. You read old trappers accounts and they're crossing places that we consider desert today like eastern Wyoming or parts of Utah and they're just finding ponds and wetlands and beavers everywhere, so it was once a much lusher landscape. We also drained lots of wetlands for agriculture, and of course climate change is fueling drought, so certainly trapping out beavers was certainly not the only thing contributing to drought in the American West. But we eliminated the animal that was keeping North America hydrated.

A beaver lodge in the Ruby Mountains of Nevada. (Photo: Ben Goldfarb)

DOERING: So, what do beaver ponds actually look like on the landscape, and what do they do for a stream?

GOLDFARB: In kind of a beaver rich stream, right, all of those beaver dams basically act as speed bumps: slowing the water down, spreading the water out and inundating the flood plain. I mean, connecting a stream with its floodplain is really really essential. We tend to think of streams as kind of these clear, straight, fast-moving, free-flowing channels, kind of the prototypical babbling brook. But, a system with its historic beaver population in it would look very different in a lot of respects, right? I mean, of course, beavers slow down water, they create these broad sluggish ponds and wetlands. There are dead and dying trees everywhere as rising water levels kill trees; the side channels twist all over the landscape. It looks kind of messy or chaotic. But of course, those kinds of chaotic seeming streams are in many cases healthier. Those dead trees, for example, are fantastic habitat for woodpeckers and owls and porcupines and all kinds of critters. Those inundated flood plains and meadows are great for moose and all kinds of other wild ungulates. It's a really really valuable landscape, and I think that we've forgotten that because our historical picture tends to omit beaver.

DOERING: A couple of decades ago, people were trying to bring back salmon and allow them to migrate back up to the streams where they spawn. and they looked at beaver dams and they said, whoa, how are they going to be able to navigate these structures, they’re impeding the fish from moving. How accurate is that assessment?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, you hear that a lot, that beavers create salmon barriers, and then there are places where there are environmental groups tearing out beaver dams to increase salmon passage. I mean, to me, from a common sense standpoint, clearly we once had millions or even hundreds of millions more beavers than we do today, we also had incredibly robust salmon runs. Obviously these two animals are somewhat co-adapted, right? And there's a bumper sticker that I love, which is that “beavers taught salmon to jump.” Salmon have all kinds of ways of getting around beaver dams. They can jump them, they can get swim around them during high water. Beaver dams are not like human-built concrete dams. They're not these impermeable obstacles. So, I think that fish have lots of ways of getting around beaver dams, and in fact we know that beaver dams create fantastic fish habitat. If you're a baby salmon, you don't want to live in some kind of fire hose-like main channel that's going to blow you downstream. You want some nice side channels and backwaters and pools. You want this really great diverse slow water habitat that beavers create.

DOERING: Obviously, you're a big fan of beavers, but not everyone is convinced that they are necessarily good for the landscape or that they should be entitled to live on private land and cause floods and cut down trees. What happens when beavers do that and how do the landowners respond?

GOLDFARB: Yeah. You know, look, I mean, even the most devout beaver believer is not naive about the problems that beavers can cause, right? I mean they're hard animals to live with. They're meddlers just like we are, and they do cut down valuable timber and they clog up road culverts. So, the kind of traditional response, if beavers are causing a problem, is to eliminate the beaver, right, trap the beaver out. And that can temporarily alleviate the problem, but there are kind of two issues with that approach, which is that first, I mean, of course you're eliminating the great pond and wetland habitat that beavers are creating, and second you’re really putting up a vacancy sign for the next family of beavers, right? As long as the habitat is good, the beavers will be back at some point. So, a lot of people I talked to in the book are advocates of these contraptions called flow devices which are basically these pipe and fence systems that you can use to pass water through a beaver dam or through a road culvert and kind of regulate the height of the pond that way, and sort of strike a compromise between human and rodent, where there's enough water for the beavers to persist but not so much that your road or backyard is totally submerged.

Skip Lisle does a spot of maintenance on one of his Beaver Deceivers, devices that protect roads from beaver-related flooding without having to kill the offending rodents. (Photo: Ben Goldfarb)

DOERING: And even some people who maybe initially were anti-beaver or thought, OK, if they're on my land they need to just be trapped out, like ranchers who need to grow a lot of grass for their cattle, the beavers might be flooding some of that land. You talk about some of them who actually convert from believing that they need to get rid of the beaver to saying, wait a minute, they're helping store water. Who are those people?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, that's, to me that's one of the most exciting directions in the beaver believer movement is the agricultural community, who historically has been very anti-beaver, as you say, because beavers, among other things, dam irrigation ditches and can be kind of a pain in the butt for that reason. In northeast Nevada, where one of the chapters of the book is set, there's this great cluster of ranchers where they were ranching in these very overgrazed ecosystems and they agreed to sort of reduce some of the grazing pressure and that that helped the vegetation like willow recover and that basically invited in the beavers. I think their first impulse was maybe to get rid of the beavers, but they let them stay, and beavers built dams and created these amazing ponds and wetlands and that had two great impacts. First, they're providing this great water source for cattle in this very arid northeast Nevada landscape. So, during times of drought when other ranchers actually had to truck water to their livestock because there was no water on the land, the guys, like this guy, John Griggs, had water on their landscape thanks to beavers. The other big impact is in a beaver pond there's all of the water that you can see, the visible surface water, but there's also water being forced into the ground, raising the water table and basically sub-irrigating all of these grasslands. There are ranchers who have seen fantastic grass production increases thanks to the return of beavers, and have become beaver believers for that reason as well, because if you're a rancher, grass is money.

DOERING: One complaint about beaver pond or dams in general is that all of that water that stagnant locks up and releases methane, which is a very potent greenhouse gas. What are the greenhouse gas impacts of beaver dams?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, so as you say, we do know that beaver dams, or beaver ponds, rather, release large amounts of methane. There's all of this decaying organic matter in a beaver pond, all of the leaves and sticks and insect bodies that get trapped in there, and as that stuff breaks down, we know that there is a release of methane. So, there have been studies sort of suggesting that beavers are, of course, a very minor contributor to climate change compared to all of the stuff that we humans do, but are maybe climate change contributors nonetheless, to a very small extent. However, of course, they're also sequestering lots of carbon, right? I mean, not all of that stuff is breaking down especially when the beaver pond is active and all of that organic matter is covered in water. They're actually sequestering huge amounts of carbon, and I think that one of the big findings from scientists who have studied this so far, which again is not many, is that beaver ponds, they're storing much more carbon when they're active, when the beavers are able to remain on the landscape doing their thing. What is sort of the net result of all of this carbon sequestration and methane release? We don't really know whether beavers are net positives or negatives, but there is certainly lots of research happening right now, and some of the studies I’ve seen, from places like the Colorado Rockies suggest that beavers could be pretty substantial carbon sequesters.

Ben Goldfarb is an environmental journalist, editor, and Beaver Believer. (Photo: Terray Sylvester)

DOERING: And, in fact, actually beavers might be able to help us cope with some of those consequences -- wildfires, heat waves, droughts. Can you talk a little bit about that?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, we know that beaver wetlands provide some degree of firebreak. There's this really wonderful pond in the Methow Valley that I visited. You know, again the Methow is this very dry place. It's been hammered with fire in the last several years, and one of the ponds there -- it was amazing -- you could see that one side of the pond had been totally scorched and the other side remained green. It was clear the fire had hit the pond and basically hadn't proceeded any further. The ability of beavers to act as firebreaks is again one of those things that hasn't really been quantified in any kind of meaningful way. As for drought, that's another thing. How much can beavers help us compensate for the loss of glacial melt and snow pack that are so important in the American West? We know that beavers can take these seasonal streams and turn them perennial. We know they're storing lots and lots of water, but how much of that water is reaching downstream users? To what extent can they compensate for some of these catastrophic climate impacts? We just don't know the answers to these questions yet. So, there's lots of beaver research happening right now all over the American West looking at beavers and climate change, and I think the next the next five to 10 years will hopefully have some really interesting results on the beavers as climate adaptation tool front.

DOERING: Ben Goldfarb is the author of "Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter". Thank you so much, Ben.

GOLDFARB: Thanks for having me. That was really fun.

CURWOOD: Author and journalist Ben Goldfarb, speaking with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Related links:

- About Ben Goldfarb and his book Eager

- Listen to our previous interview with the filmmaker of “The Beaver Believers”

- About the Methow Beaver Project

- Learn more about Skip Lisle’s “Beaver Deceiver” devices

- Science Magazine: “What Role Do Beavers Play in Climate Change?”

[MUSIC: Saturday Night Live Band, “Gotta Keep My Eyes On You”]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Thurston Briscoe, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I’m Steve Curwood -- Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong clean energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth