November 23, 2018

Air Date: November 23, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Keystone XL Blocked Again

View the page for this story

A year and a half after President Trump reversed an Obama Administration decision to block TransCanada’s Keystone XL pipeline, a federal judge has halted the project again, saying the environmental review of the project is insufficient. Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau tells Host Steve Curwood about the decision and what this means for the controversial pipeline’s future. They also discuss recent pre-trial developments in the Juliana v. U.S. case, brought by young plaintiffs who seek to compel the government to protect the climate of this planet they will inherit. (10:16)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood take stock of the climate preparedness of US naval bases before turning to a study about bees swarming an experimental hemp field. Then, the pair looks back to the 1970s, when the Environmental Protection Agency ordered lead out of gasoline. (03:53)

Emerging Science Note: Coral Reefs Wrecked By Rising Seas

/ Sarah RappaportView the page for this story

Research from the University of Exeter indicates warming waters and ocean acidification aren’t the only climate impacts coral reefs are facing: rising sea levels mean cloudier water that hinders coral reef growth. And as Sarah Rappaport reports in this week’s Note on Emerging Science, that’s bad news for fish that depend on coral reefs, and coastlines that benefit from their ability to protect the shore from waves. (01:59)

Fighting Climate Change, Naturally

/ Aynsley O'NeillView the page for this story

Climate mitigation often focuses on technical solutions. But experts say as much as one-fifth of the United States’ current carbon emissions could be offset through “natural climate solutions,” which manage and restore land. Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill reports. (03:29)

Let The Leaves Be And Feed The Birds

View the page for this story

Autumn brings fallen leaves in temperate zones, and the chore of raking all those leaves into piles. But it turns out that a lazy fall yard-work ethic can help native birds. Tod Winston of the Audubon Society explains to Host Steve Curwood why leaving fallen leaves and dead flowers helps insects that are food for birds. (07:51)

BirdNote®: How Much Do Birds Eat?

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Flying burns a lot of energy and in general, the smaller the bird, the more food it needs relative to its weight. Hummingbirds ingest about 100% of their body weight every day, while the food we humans eat each day adds up to just about 3% of ours. BirdNote®’s Mary McCann puts how much birds eat in the context of human fare. (02:01)

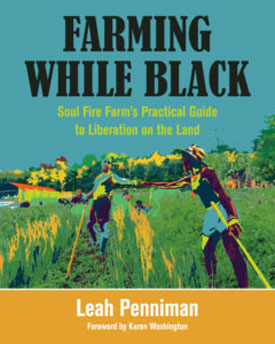

Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land

View the page for this story

Soul Fire Farm in upstate New York is dedicated to not only growing food, but also cultivating environmental, racial and food justice. Its ten black, brown and Jewish farmers aim to dismantle racism within the food system while reconnecting people of color to the earth. Leah Penniman is the co-founder of Soul Fire Farm and joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss her new book, Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land, and her journey as a woman of color reclaiming her space in the agricultural world. (16:32)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Pat Parenteau, Leah Penniman, Tod Winston

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Aynsley O’Neill, Mary McCann, Sarah Rappaport

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Good news for the lazy gardener. Leaving those fallen leaves on the ground and dead flowers standing helps feed the birds.

WINSTON: In a flower garden, leave the flower heads of beautiful flowers like sunflowers, black-eyed susans, coneflowers - those seed heads provide millions of seeds that last through the winter and provide a smorgasbord for birds to feast on all winter long.

CURWOOD: Also, a black woman’s journey to reclaim a lost part of her culture and take up farming.

PENNIMAN: Contrary to popular belief, black and brown folks do want to farm. And, this was something that just surprised me, cause I thought I was just a weirdo out here. I was going to start this farm with my family, grow food, you know, provide to those who need it the most in the community, and that was going to be it.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Keystone XL Blocked Again

A group of Keystone protestors from 2014. If the Trump Administration wants to see the Keystone XL Pipeline built, its approval will only come after a thorough review of its potential environmental impacts. (Photo: Joe Brusky, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

We have two major environmental cases on tap for our broadcast today. The US Supreme Court recently refused to block a trial for Juliana v the United States, a potentially monumental case brought by young people that seeks to require the federal government to provide a livable climate in the future. The way forward is still unclear for that case, and we’ll have more about it in a few minutes. But first we turn to a ruling by a federal district judge in Montana that blocks the Keystone XL pipeline unless and until a better environmental impact assessment is made. Here to discuss is Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau joining us from Ireland – Welcome to Living On Earth, Pat!

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Steve. Good to be here.

CURWOOD: So, tell me, exactly what did the judge decide in this ruling on Keystone XL?

PARENTEAU: Well, his main ruling was that the Trump administration completely disregarded the climate effects of building the Keystone pipeline. It's just another major infrastructure investment, of course, in fossil fuels. And the Trump administration dismissed the whole idea that it would be contributing to climate change with barely a paragraph in the decision document that they issued. And the judge said that's not good enough, you really do have to take account of the growing body of science that we all know. And you have to explain why it makes sense, given that, to authorize yet another major piece of infrastructure that will take 40 years to pay off.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, Pat, when the request was first put in for a Keystone XL, there were different economics than today, how did those play into the judge's decision?

PARENTEAU: Yes, in the earlier round - and this, of course, it was actually during the Obama administration - the state department concluded that one way or another, given the price of oil, Keystone Pipeline, the oil was going to get to the market one way or another, either through the pipeline or through rail transport. And therefore, the state department concluded it really doesn't matter whether we approve this pipeline or not, in terms of climate change. What's changed, of course, from that is that oil prices have declined significantly, have not rebounded. And now, the conclusion of marketers and economists is that without the pipeline, this heavy crude oil from Canada would not get to the markets.

CURWOOD: Now, to what extent, Pat, were you surprised by federal judge Brian Morris' decision in this case? What's his reputation?

PARENTEAU: Well, he's a former Supreme Court judge on the Montana Supreme Court. His profile is a very moderate judge, he's hardly a radical environmentalist. There are some judges on the federal bench who are more pro-environment. Judge Malloy, in Montana, has issued a number of very, I would say, favorable decisions from an environmental standpoint, but Judge Morris isn’t in that same category. He is definitely a moderate.

A group of the youth plaintiffs in the Juliana V. United States cheer earlier this year when the ninth court rejected the Trump Administration’s bid to dismiss the case before trial. (Photo: Robin Loznak)

CURWOOD: So, the Indigenous Rights Network and the other advocates who are plaintiffs in this case see this as good news. How bad is this news for Trans Canada, the company behind the construction of the pipeline?

PARENTEAU: You kind of wonder if it's true that the market for this oil has gotten really weak, you kind of wonder if maybe they aren't doing Trans Canada a favor by giving them a chance to rethink whether it makes sense to continue with this, at least at this point in time. I can't answer that question. I'm not an expert enough on the oil market to judge, but it's interesting that we haven't heard a huge outcry yet.

CURWOOD: So, in other words, you're saying that Trans Canada may have, may see this as a blessing in disguise, that instead of running up its debt tab to build this thing out, they can back away from it and tell their investors and friends, well, the court made us do it.

PARENTEAU: At least it gives them that opportunity to rethink this. I'm not speaking for them, obviously, they may go forward, but they've got a chance to rethink it.

CURWOOD: Now, along with the changing economics, I gather that the plaintiffs and both the judge cited other issues, such as the risk of spills. And of course, what would happen to cultural resources. What were the findings?

PARENTEAU: Yes, there's been so many episodes of spills of pipelines. And in fact, recently, a report came out showing all the explosions that have occurred at pipelines, over 100, within the last couple of years, I think, is the timeframe they were looking at. These kinds of infrastructure, you know, they have problems for sure. And the Indigenous Rights Network is concerned, because these pipelines run through, of course, a lot of what we call “Indian country” where native people still have a large number of burial sites, archaeological resources, cultural resources. And just like the DAPL case, the Dakota Access Pipeline, the tribes are insisting on greater respect, and higher level of security, and a higher level of maintenance monitoring on these pipelines, what kinds of contingency plans do you have in place to respond quickly to spills. They're pushing hard for much tighter regulation of the pipelines than historically we've seen.

CURWOOD: So what happens now? I mean, how long would the environmental impact statement take, do you think?

PARENTEAU: You know, typically, it takes a year, just because the wheels of government tend to move as slowly as they do. I suppose you could do it faster than that, if you put it on some kind of a fast track, but I think we're looking at least a year's worth of extra work before another supplemental EIS, environmental impact statement, is done, the public has given a chance to comment and then another decision is made. So, I think it's going to be a considerable period of time before we know what the fate of KXL really is.

CURWOOD: Pat, it's hard to overstate the symbolism of Keystone XL Pipeline for pipeline opponents. I mean, people went and marched at the White House, went to jail. To what extent do you think that that could be part of the reason that the Trump administration decided to resurrect this fight now?

PARENTEAU: Well, that's a good point. The Trump administration seems to like these high profile fights. They look for them. They seem to like giving the environmental community a black eye, and what they perceive to be, I suppose, is liberal democrats that have stated their opposition, including Nancy Pelosi has gone on record as opposed to Keystone Pipeline in the past. So, you know, this is the kind of fight that Trump seems to like, and so far, it's when he's not winning. But of course, that's never stopped him from claiming victory anyway.

CURWOOD: All right. Professor Parenteau, your crystal ball. Keystone XL ever gets built, do you think?

PARENTEAU: I don't think so. It just looks to me like we've been dealing with this issue now for how long, it seems like eight years or more. And it feels to me, and it’s just a feeling, that history is against this pipeline. It feels to me like it's a turning point. And so we'll see.

CURWOOD: Alright, Pat. Thanks. Now, let's talk about this other case. This is the Juliana v. the United States, where essentially kids are suing, saying that the government needs to move to help assure them a livable climate in the future years ahead. This case has been delayed by the federal government many, many times. How many times now has it gone up to the Supreme Court where the Supreme Court says no, no, no, you do have to let this go ahead.

Former EPA Regional Counsel Pat Parenteau is a professor of environmental law at Vermont Law School (Photo: courtesy of Vermont Law School)

PARENTEAU: Well, let's see, initially, Justice Kennedy, when he was still on the court denied a request to stay the case. Then the government went back to the Supreme Court and got Chief Justice Roberts to issue a temporary stay on the case. And then Justice Roberts convened the full court to decide whether they should continue the stay of the trial. And the full court voted actually 6 to 2 not to do that, but also suggested that the Ninth Circuit take another look at whether the case should proceed. So that's where the case is currently, back in front of the Ninth Circuit. By my count, this is actually four times that the government has asked the Ninth Circuit to stop the trial. And so we're all waiting to see what the Ninth Circuit does with this fourth, and I hope final round, of whether we're going to have a trial or not.

CURWOOD: Why is the plaintiff’s argument so groundbreaking?

PARENTEAU: Well, it's groundbreaking because no court has ever been asked to literally order the federal government to adopt a plan to achieve a science-based strategy for reducing carbon emissions that will stabilize the earth's climate. I mean, that’s just saying, it indicates how novel and extraordinary it is. It's an extraordinary remedy for an extraordinary problem is the way I like to put it. But the plaintiffs are saying to the courts, to the Supreme Court, the Ninth Circuit, let us build a record for you and give you the benefit of some really high-quality evidence. They've got an all-star cast of scientists and economists lined up ready to go, let us build a solid record and then you can make a decision, and if your decision, fully informed, is that we have no case and there is no remedy for the problems that we're presenting, so be it. But don't try to make a decision in the abstract.

CURWOOD: This case, Juliana v. the United States, was filed back in 2015. That was before we had Hurricanes Maria, Harvey, Irma. Before we had really, almost a firestorm in California that recently killed a record number of people, before the climate really started biting back in such a hard way. How might the news of climate disruption these days affect how this case moves forward?

PARENTEAU: It should. I mean, 2017, according to the latest data from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, was the most destructive hurricane season on record. It wasn't necessarily the most destructive hurricanes, but the economic damage was the highest ever in the history of the United States. And the fact that these storms are more intense that they're amplified by global warming and climate change is clear. So, therefore, for a court to say, even in the face of that kind of mounting evidence of clear, unmistakable, and even horrific damage and loss of life, to say that there's no remedy it strikes me that a thoughtful judge would hesitate to write an opinion like that. That's what the hope is, that the light will go on, in the court, and at least some type of decision that moves the needle in the direction it needs to go happens.

CURWOOD: Pat Parenteau is currently a Fulbright fellow and a Professor at Vermont Law School. Thanks, Pat, for taking the time today.

PARENTEAU: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- The Guardian | "Keystone XL pipeline: judge rules government 'jumped the gun' and orders halt"

- Our Children’s Trust (Juliana Plaintiffs) November 21, 2018 statement on pretrial maneuvers

- Pat Parenteau Faculty Bio

- Vox | “A major climate change lawsuit is on hold. Again.”

[MUSIC: Scott Alarik, “Colorado Trail” on All That Is True, by Carl Sandburg/Lee Hayes, MWorks Studios]

Beyond The Headlines

The littoral combat ship USS Fort Worth (LCS 3) provides a sea-going platform for UH-60A Black Hawks, seen here off the coast of Oahu, Hawaii. (Photo: U.S. Pacific Fleet, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Time now to take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter’s an Editor with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and DailyClimate.org, on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia – hey there, Peter, what’s going on?

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve. You know, there’s been a lot in recent years about climate change and sea level rise and their impact on the military. It has a particularly strong impact on the Navy because obviously, no brainer, all of the Navy’s facilities are at sea level.

CURWOOD: So which ones are most endangered, though, by the rising sea level?

DYKSTRA: Quite a few. But our friends at Inside Climate News just had a report on the four US Navy facilities that have dry docks that can accommodate nuclear vessels, aircraft carriers and submarines. Those four are in Hawaii, Washington state, the state of Maine and of course the huge naval complex in Norfolk, Virginia.

CURWOOD: Oh yeah I’ve been to Norfolk. There are a lot of houses on stilts, the place gets flooded pretty easily.

DYKSTRA: Right, and the navy base is already seeing some of the impacts of flooding. There’s a 21 billion dollar proposal to update and renovate navy bases. A good part of that is to make them more resilient to climate change and sea level rise.

CURWOOD: Hmm. Where else is the military at risk?

DYKSTRA: Well the Air Force, Marine training bases, the Army, a lot of their facilities are at, or near the coast as well. Just this Hurricane season we saw Tyndall Airforce base in the Florida Panhandle absolutely laid to ruin by Hurricane Michael. And another one not too far from there, MacDill air force base, just South of Tampa, is the headquarters for Centcom, the central command that governs all US military activity in the Middle East.

Hemp fields in Colorado have been attracting bees in the late season. (Photo: Maja Dumat, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So hey, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: I’m looking at the work of a student at Colorado State University named Colton O’Brien – some pioneering research when he noticed that fields, experimental hemp-growing fields, were drawing an unusual number of bees.

CURWOOD: Well, of course, I understand that beekeepers use smoke to handle their bees, but this is something else.

DYKSTRA: Different kind of smoke, different kind of buzz, because we’re talking about low THC, low hallucinogenic value hemp that’s used for fabric. He found 22 different varieties of bees flying, and buzzing, and collecting pollen in this experimental hemp field.

CURWOOD: And why was that? Why do the bees like hemp?

DYKSTRA: Well it was August and there are very few other flowering plants or crops that have flowers and pollen available in August so the bees were drawn to the hemp.

CURWOOD: So, let’s take a look back now in the history vault, and see what you see for us?

DYKSTRA: November 28th, 1973, 45 years ago this month, the EPA set its final rules on a phase-out of leaded gasoline after years of study saying that low IQs and slow brain development were the result of lead exposure among kids.

CURWOOD: So what’s happened since then?

DYKSTRA: What’s happened since then is that things have improved; blood-lead levels are a lot lower, IQs among kids have gotten higher, and it’s been a real victory for the environment and for human health.

CURWOOD: So, lead is outlawed in the United States – where’s it legal?

DYKSTRA: The United States. We still use it for leaded gasoline in general aviation, propeller planes. In a few countries it’s still completely legal for cars, countries like Iraq and North Korea, most of the world has outlawed it and seen the benefits of unleaded gasoline.

Propeller planes are some of the few remaining motorized crafts that can legally use leaded gasoline in the US. (Photo: jimflix! Flick CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra’s with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and DailyClimate.org. Thanks Peter, we’ll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, thanks Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website loe.org.

Related links:

- The Inside Climate News Report on Naval Bases and Climate Change

- Low THC Hemp Colorado Study

- EPA: Lead Laws and Regulations

[MUSIC: Christian McBride Trio, “Fried Pies” Live Studio Session

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dhsi_p-KSG4]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Looking to the trees and grasses for natural climate solutions. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Don’t go away!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Peace” on Spirit, by Horace Silver, Jazz Legacy Productions]

Emerging Science Note: Coral Reefs Wrecked By Rising Seas

A tropical coral reef. (Photo: Courtesy of NASA)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Just ahead, how natural climate solutions can be cheaper and easier than technology-driven ones. But first, this note on emerging science from Sarah Rappaport.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

RAPPAPORT: Coral reefs are known throughout the tropics for their vibrant colors, diverse formations, and the habitats they provide for a staggering 25 percent of all marine species. While they may look like colorful rocks, corals are actually made up of colonies of individual invertebrate animals, called polyps. Worldwide, coral polyps are threatened by warming waters, ocean acidification, and overfishing. New research indicates that sea level rise from climate change can also be added to the list. That’s according to a recent study published in the journal Nature.

Researchers from the University of Exeter found that coral reefs may not be able to grow fast enough to keep up with rising seas. That’s because sea level rise can lead to more erosion and sediment in the water.

Sediments cloud the water and make it difficult for symbiotic algae living on the coral to access enough sun to photosynthesize. Without algae producing food for the coral polyps the corals essentially starve and die. The team looked at about 200 coral reefs in the Caribbean and Indian Oceans. They used four different climate change prediction scenarios and they found that even under modest sea level rise, only three percent of Indian Ocean reefs would be able to grow enough to keep pace with rising seas.

That’s bad news for both marine species and coastal communities. Coral reefs protect coastal areas from storm damage by slowing down the impact of waves. They’re also a vital habitat for marine life and a nursery for thousands of species of juvenile fish.

Scientists say reducing greenhouse gas emissions is the best way to save the world’s corals and avoid permanent damage to one of the world’s most complex, and beloved, ecosystems.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Sarah Rappaport.

Related links:

- More on this coral research

- The Coral Reef Study

Fighting Climate Change, Naturally

Some of the most effective natural climate solutions include the restoration of forests, wetlands, grasslands and other ecosystems. (Photo: Pacific Southwest, Region 5, US Forest Service, USDA, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: A lot of talk about tackling climate change focuses on technical solutions, like fuel-efficient cars and solar panels. But, there are also so-called “natural climate solutions,” which focus on better management of our ecosystems. A study from the Nature Conservancy suggests how things like letting trees and grasses grow could have a huge impact. Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill has been looking into the study.

Hey there, Aynsley.

O’NEILL: Hi, Steve. So, in this report, The Nature Conservancy tried to quantify what improved management and restoration of the land could do to help stabilize the climate.

They looked at how much carbon could be sequestered by such things as leaving grasslands intact and not turning them into agricultural fields. They also looked at the impact of planting trees or restoring wetlands. In fact, there are some twenty-one different natural climate solutions that they investigated. Here’s Joe Fargione, lead author of the study.

FARGIONE: Our study shows natural climate solutions can help fight climate change with a potential benefit that's equivalent to one-fifth of our nation's current net emissions. And that's the same as if every car and truck in the country stopped polluting the climate.

O’NEILL: And Joe Fargione says that if we implement all twenty-one of these approaches, it could set us on the path to meeting our obligations for the Paris Climate Agreement.

FARGIONE: If you look at between now and 2030, if natural climate solutions were ramped up, that could address about 37% of the reduction in climate pollution needed to keep warming well below two degrees, which is, of course, the target that was agreed to at the Paris Agreement.

O’NEILL: One thing we could improve is the US Agriculture Department’s Conservation Reserve Program, where farmers get paid to take marginal land out of crop production, and replant it with native species. Joe Fargione says, since 2007, we’ve lost 13 million acres from that program.

FARGIONE: We estimate that if we put all of that land back into the Conservation Reserve Program, you would get about 9 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent stored per year, the same as taking 2 million cars off the road.

Natural climate solutions have the ability to offer 37% of the carbon mitigation needed through 2030, but only receive 0.8% of public and private climate financing globally. (Photo: Greenfleet Australia, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Wow, Aynsley, that’s huge. But how difficult would it be to actually put some of these into practice? It sounds kind of expensive.

O’NEILL: Well, some of these ideas are expensive. But the Nature Conservancy report details some low-cost strategies, like planting cover crops and improving how we manage animal waste. I spoke to Benton Taylor, a postdoc at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. He told me one of the easiest, cheapest, and most effective natural climate solutions is passive – just letting trees reforest themselves, which is practically free!

TAYLOR: When we look at sites that that have been passively versus actively reforested, we don't really see much of a difference in how quickly they get to the sort of old growth forest standard that we're looking for. So, it turns out that nature does a very good job of reforestation on its own. It is much less expensive to passively reforest.

O’NEILL: So, Steve, if we take away the incentives to cut down forests and let them regrow, we could save a lot of effort and money, which we could use to mitigate climate change in other ways.

CURWOOD: And of course, there are lots of benefits to reforestation other than carbon capture.

O’NEILL: Yeah, and Benton Taylor made that point to me as well.

TAYLOR: Reforestation is good for, sort of, counting beans when we're thinking about carbon, but it's also good for a lot of other things biodiversity, soil stability, that sort of thing.

CURWOOD: Alright, thanks, Aynsley, for that report.

O’NEILL: Sure thing, Steve.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill.

Related links:

- New York Times | “Part of the Answer to Climate Change May Be America’s Trees and Dirt, Scientists Say”

- Click here to read the study in Science Advances

- The Nature Conservancy

- Joe Fargione at The Nature Conservancy

- Benton Taylor’s Website

[MUSIC: David Mallet, “Garden Song” on David Mallet (1978), Neworld Media]

Let The Leaves Be And Feed The Birds

Many birds, like the Black-Capped Chickadee, rummage through the leaf litter in fall and winter in search of the seeds and bugs that may be hiding underneath. (Photo: Tom Murray; Flickr CC)

CURWOOD: It’s about that time when many homeowners get out the rake and pile up all those fallen leaves, that is, if their yard isn’t already covered in snow. But it turns out that a lazy fall yard-work ethic can actually be big help for native birds. The Audubon Society provides tips on how to use leaf litter to create helpful spaces for birds in your own back yard. Tod Winston is a Birding Guide and Research Assistant for the New York City Audubon Society, and joins me now.

WINSTON: Thank you so much, happy to be here.

CURWOOD: So tell me, why would keeping a messy fall yard be a benefit for birds?

WINSTON: Well, you know, in so many areas where people live, an aesthetic has taken over, over the past decades that is something like a pristine English estate, you know of lawn, and house, and not much more, a few ornamental shrubs. And that habitat is something that people feel comfortable with. But it's really not a habitat that's made for birds and wildlife. And something approximating more of a wild habitat can provide a much richer habitat for the wildlife and birds that so many of us love.

CURWOOD: Wait a second, though, I mean, this is such a wonderful thing to do in the fall, you get the family together, you all get out there raking and you do pruning and everything looks all neat and tidy afterwards. And it's a whole ritual.

WINSTON: So, I'm remembering lovely times, raking the leaves, I guess that you remember the good parts of it, it wasn't all lovely. But I remember raking the leaves with my father and grandfather, that was something we all did in the fall, it was something that was expected of us. But I guess what I would recommend though, is leave a space that is a happy place for birds and wildlife to spend the winter and you know, that's something that will reap benefits throughout the entire year, not just the wintertime.

CURWOOD: So Tod, what can you do to keep up what you call a messy yard?

It may be customary to rake leaves in the fall, but taking a break from the yard work may help the wildlife in your backyard by providing them food and shelter. (Photo: Jessica Quinn; Flickr CC)

WINSTON: So, you know, there are a number of things to think about, and one is certainly to leave the leaves on your property or rearrange them at least, so that they can provide a nice leafy rich understory for critters to overwinter in. Another is to, in a flower garden, leave the flower heads of beautiful flowers like sunflowers, black-eyed susans, cone flowers, those seed heads provided millions of seeds that last through the winter, and provide a smorgasbord for birds to feast on all winter long. Another way to provide a great habitat for birds is to create a brush pile of fallen branches or pruned branches. And you can do that by building a brush pile with larger branches underneath and smaller branches above; that creates an amazing shelter for all sorts of critters, including birds. And related to those dead branches is to leave dead branches where they fall and leave, if you can, snags or dead trees standing, which are great habitat for woodpeckers. Woodpeckers will excavate holes that, then, all sorts of birds like chickadees, and titmice, nuthatches will also nest in. So you know many of us in our desire to clean up our woods remove dead trees and those dead trees are really important for birds.

CURWOOD: Of course under leaves, one finds worms, right?

WINSTON: Right. So there are all sorts of critters that live under leaves, and some are good for birds, worms, and particularly moth pupae, you know, you see moths and butterflies and you don't often think about, a lot of us, I think, that all moths and butterflies are in cocoons, like a monarch butterfly on a plant. But actually, the vast majority of moth pupae are in the ground. Those moths, that caterpillars that are munching on leaves when they're ready to metamorphose they dropped to the ground. And so on a property without a rich ground habitat of leaves, those moths have nowhere to create their pupae and create a new generation of moths. And, come springtime many birds, forest birds depend on all the critters that live in the leaf litter - beetles, moth pupae, worms. As well, many creatures that are beneficial to the garden - praying mantises, lace wings, ladybugs, they all over winter in that leaf litter. So if you - you're actually doing your garden a service by leaving that leaf letter and providing habitat for critters that are beneficial to the garden.

CURWOOD: Tod, you must have some tips for folks who are really avid bird fans.

WINSTON: You know, a lot of folks who first get into birding are shocked when they just start to listen and open their eyes to see what lands in their, as birders say, patch. And that means just see what shows up where you live. An important thing to think about look to see what's growing there. You may have native plants that are really important for birds that are right there and you don't have to buy them, all you have to do is give them a chance to thrive in your yard.

CURWOOD: So, what specific varieties of plants do you recommend to encourage visitation from our feathered friends where I am, we have actually an invasive species an autumn olive that well the bird seem to like that.

WINSTON: Well, you know, like people like potato chips and Cheetos, birds like shrubs like the autumn olive. Autumn olive berries are kind of tasty, I kind of like them myself, but that really is part of the problem with non-native shrubs that have been planted and have escaped and spread all over the United States. Plants like autumn olive, multiflora rose, bitter sweet, Japanese honeysuckle, the list goes on and on. Those are plants, all of which have tasty berries that birds like, and birds eat those berries and then spread the seeds all over the place.

Tod Winston is a Research Associate with the NYC Audubon Society. (Photo: NYC Audubon Society)

But when it comes to the spring time, and birds need bugs to feed their babies, those non native plants don't have, host a rich insect life and do not provide the protein that, via insects, that birds need to feed their babies. That's really the problem. So when we're thinking about what to plant in our yards we should be thinking about what birds need all year round. There are many kinds of shrubs, service berry, and trees, black cherry, that are native to where we live, at least here in the in the northeast. And there are varieties and of those plants across the United States that can be great for birds.

CURWOOD: Tod, you live in New York City. Where do you live, a place where you have control over your yard?

WINSTON: I live in an apartment on the third floor of a little apartment building. But you know, even people who live in urban settings can put some native plants on their balcony or on their patio. And those plants could be useful both to breeding birds and to migratory birds that pass through the city.

CURWOOD: By the way, talk to me about the history of yard work. Why do people rake up the leaves in their yards to begin with?

WINSTON: You know, I honestly don't understand that, people are obsessed with being neat and tidy. You know. And that is a basic part of it, that people are afraid of the disorder, afraid of what's lurking in those leaves. And, you know, part of this effort to get people to connect to the nature in their backyards, to have positive impact for the nature in their backyards, is to connect them to what lives in that leaf litter. They're all sorts of fascinating creatures and beautiful creatures that depend on messiness, that depend on native plants. And, you know, just like new birdwatchers, people who are new to really observing what's in their gardens can be amazed by the variety of life that live there.

CURWOOD: Tod Winston, birding guide and research assistant for New York City's Audubon. Tod, thanks for taking the time with us today.

WINSTON: Thank you so much for having me on. It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Learn more about local birds in your neck of the woods

- Find out which plants are native to your neighborhood

BirdNote®: How Much Do Birds Eat?

A Black-Throated Blue Warbler with a fat, juicy berry. (Photo: Kenneth Cole Schneider, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

[BIRD NOTE THEME]

CURWOOD: You may still be digesting this year’s Thanksgiving feast, or

working it off at the gym. But as BirdNote®’s Mary McCann tells us, all that turkey, stuffing, and pie is nowhere near how much a bird eats relative to its weight.

MCCANN: There used to be a saying about somebody who doesn’t eat much — “she eats like a bird.” Just a little of this and a smidgen of that. But how much does a bird typically eat? And how much would you have to eat to match it? Well, depends on the bird.

As a rule of thumb, the smaller the bird, the more food it needs relative to its weight. A Cooper’s Hawk, a medium-sized bird that hunts other birds, eats around 12% of its weight per day. For you, if you weigh, say, 150 pounds, that’s 18 pounds of chow — roughly six extra-large pizzas.

[Calls of Cooper’s hawk [140257] recorded by Gerrit Vyn]

[Calls of Black-capped Chickadee http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/117803 :08 on]

That perky little chickadee flitting back and forth for sunflower seeds from your feeder eats the equivalent of 35% of its weight. You, as a 150-pound chickadee, will be munching 600 granola bars a day.

A Rufous Hummingbird sips on sugar water at a feeder. (Photo: © Mike Hamilton)

And a tiny hummingbird? It drinks about 100% of its body weight per day. That means you’ll be sipping 17 and a half gallons of milk. Prefer wine or beer? 18 gallons.

If it’s warm outside, you can probably get by on a bit less. But if it’s cold, you’ll need more, so you’d best stock up.

I’m Mary McCann.

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Call of the Pine Siskin provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. [44845] recorded by G.A. Keller, [140257] recorded by Gerrit Vyn, and [117803] recorded by S.R. Pantle.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

© 2005-2018 Tune In to Nature.org November 2018 Narrator: Mary McCann

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/how-much-do-birds-eat-each-day/

https://www.peregrinefund.org/explore-raptors-species/Cooper's_Hawk

https://www.birdnote.org/show/how-much-do-birds-eat

CURWOOD: For pictures, waddle on over to our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- This story on the BirdNote® website

- About the Black-capped Chickadee

- More on the Cooper’s Hawk

CURWOOD: Coming up – a new book, Farming While Black, the history and future of farming as a person of color. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. That’s racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Cercie Miller Quartet, “The Nearness Of You” on dedication, by H. Carmichael, Stash Records]

Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land

Run by a collective of Black, Brown and Jewish people, the mission of Soul Fire Farm is to end injustice within the food system. (Photo: Soul Fire Farm)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Leah Penniman is an activist working towards environmental, racial, and food justice through her work at Soul Fire Farm, a collective of ten Black, Brown, and Jewish farmers. Their goal is to dismantle racism within the food system while reconnecting people of color to the earth. Leah has a new book called, Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land. In it, she describes her journey as a woman of color reclaiming her space in the agricultural world, while providing a comprehensive guide for others who may want to follow her path. Welcome to the show, Leah!

PENNIMAN: Thanks so much for having me.

CURWOOD: Tell me a little bit about your journey falling in love with nature and farming, and how it has led you to create your book, “Farming While Black”.

PENNIMAN: Well, nature was my only solace and friends growing up in a rural white town. Our family was, you know, one of the only brown families, if not the only in the entire town. So, we were subjected to a lot of harassment and assault and abuse, and so, in absence of peer connection, I went to the forest and found a lot of support and love in nature. And so, when I became old enough to get a summer job, I was looking for something that kept alive that connection and was able to land a position at the Food Project in Boston, Massachusetts, where we grew vegetables to serve to folks without houses, to people experiencing domestic violence. And there was something so good about that elegant simplicity of planting, and harvesting, and providing for the community. That was the antidote I needed to all the confusion of the teenage years. So, I've been farming ever since.

CURWOOD: Now, that's interesting. A lot of people say when they connect with nature, they connect with creatures. You connected with plants, it sounds like.

PENNIMAN: Well, plants don't talk back, right?

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

PENNIMAN: No, I feel connected to the whole ecosystem, but the plants are incredible. They have these secret lives that we can't see, or even imagine. So take, for example, the trees of the forest, right? There's a underground network of mycelium that connects their roots, and they're able to pass messages and warnings. They pass sugars and minerals to each other through this underground network. And they collaborate across species, across family. And so, when we tune into that, I think we learn something about what it is to be a human being and how to live in community with each other in a way that if we're not connected to nature, we sort of lose that deeper sense of who we are, who were meant to be.

Leah Penniman is the author of Farming While Black and one of the co-founders of Soul Fire Farm. (Photo: Chelsea Green Publishing)

CURWOOD: Now, your book is not only a how-to guide for folks who are interested in pursuing a path similar to yours, but it also, well, it has some history, sociology, environmental lessons all wrapped up in this package. Why did you add those additional stories and information in with your guide, rather than it, well, having it be strictly a manual?

PENNIMAN: Well, I wrote this book for my younger self. So, after a few years of farming, I would go to these organic farming conferences, and all the presenters were white, you know, all the books were written by white folks, mostly white men. And so I started to feel this real crisis of faith in my choice to become an organic farmer, like wondering, as a brown-skinned woman, whether I had any place in this movement, if I was being a race traitor, and I should, you know, focus on housing issues, which are equally important, or some other issues. And so, in putting together this book, I was really thinking about myself as a 16-year-old and, all the other returning generation of black and brown farmers who need to see that we have a rightful place in the sustainable farming movement that isn't circumscribed by slavery, sharecropping, and land-based oppression, that we have a many, many thousand-year noble history of innovation and dignity on the land.

So, those anthropological pieces that uplift, you know, the raised beds of the Ovambo and the terraces of Kenya, and the community supported agriculture of Dr. Whatley, those are to remind us that, you know, we've been doing this all along, and we belong, and we're standing on the shoulders of our ancestors. We're not trying to create something new right now.

I mean, aside from writing it for my younger self, I'm a super nerd. And so, there was something that, you know, I had heard, for example, that Cleopatra was really into worms. And so casually, I'm telling this antidote to youth who come to our farm, right? I'm like, oh, yeah, these worms, Cleopatra was into them. She was like, into vermicomposting. But I wasn't super sure that that was true. And so in writing a book, you can't just write down anything you feel like writing, you know, you have to do research. And so this process of digging through the literature and finding and verifying these stories about our people just satisfied this academic itch that I had.

So, more importantly, though, than my personal need, we have waiting lists for our black and brown farmer training programs many years long. And so, I didn't want to be a gatekeeper any more to this really important practical knowledge, or the historical and psycho-spiritual knowledge. And so putting it in a book, just lets a lot more folks have access to the things we've learned in over a decade of practice at Soul Fire Farm.

CURWOOD: Wait a second, you have a waiting list of people who want to come to Soul Fire Farm and learn how to do this?

PENNIMAN: Right? Contrary to popular belief, black and brown folks do want to farm. And this was something that just surprised me because I thought I was just a weirdo out here, I was going to start this farm with my family, grow food, provide it to those who need it most in the community. And that was going to be it. And I got a call our first year from this woman, Kafi Dixon in Boston who said, you know, through tears, I just needed to hear your voice to know that it was possible for a woman like me to farm, and that I wasn't crazy, and that there's hope. Right? And that was the first of thousands and thousands of phone calls and emails to come of folks saying, “I need to learn to farm, I want to do it in a culturally relevant, safe, space. I want to learn from people who look like me.” And so we opened the training program and I posted on Facebook. It filled in 24 hours. So I posted another one and it filled. And that's just the way it's been. It seems that we have realized as a generation that we left something behind in the red clays of Georgia, and we want to get it back. And so we're doing our best to respond to that call at Soul Fire.

CURWOOD: Talk to me a little bit about how access, or the lack of access to healthy food can have an effect on a family, especially families of color.

PENNIMAN: So, we're living under a system that my mentor Karen Washington calls food apartheid. So, in contrast to a food desert as defined by the US Department of Agriculture, which is a high poverty zip code without supermarkets, right, a food apartheid is a human created system, not a natural system like a desert. It's a system of segregation that relegates certain people to food opulence, and others to scarcity. And there are consequences to that. We see in black and brown communities a very high disproportionate incidence of diabetes, heart disease, obesity, cancer, even some learning disabilities, and poor eyesight, and mental illness can be linked to having access to Hot Cheetos and Takis and Blue Drink, but not having access to those fresh healthy fruits and vegetables that we really need to be healthy and also to be part of democracy to do our civic duty. If I'm feeling sick, or my body is too heavy, or, you know, I'm trying to just find something to eat, I'm certainly not going to be going down to City Hall and talking about how we need fair wages for farm workers or anything like that. So food is right now a weapon in our country, when it really should be a basic human right.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about urban farming, and how that can alleviate the food apartheid situation for some families.

PENNIMAN: I'm all for urban farming, and I think we actually need to do more as a society to provide the technical support through the US Department of Agriculture and other agencies so that urban farmers can be taken more seriously and provide a greater benefit for their communities. Folks who are growing food in cities are meeting the USDA definition of $1,000 worth of products, are feeding their communities, are oftentimes doing that much more efficiently because there's no transportation hurdle to overcome. So, I think it's really unfortunate that we don't often consider urban growers as farmers.

CURWOOD: By the way, one of the most intriguing sections of your book “Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land” is this explanation of how you can clean up lead-contaminated soil, which you find in so many places in the urban environment. You have a very practical guide as to how you can use natural plants to chelate, that is, to remove lead from the soil, so that it's safe to grow food there. I don't think I've seen that anywhere else.

Soul Fire Farm is located in Grafton, New York and is active year-round. (Photo: Soul Fire Farm)

PENNIMAN: Well, that's deeply personal for me because in the same time period, when my husband Jonah and I, cleaning up soils, we would bring our newborn with us and we didn't know anything about lead in the soils at the time, and she got lead poisoning. When we went back and tested, we found around some people's homes 11,000 ppms. Now, the safe limit is 400 parts per million. So 11,000, that's a super toxic site. And these are people's yards, where children are playing. So, our daughter is fine. But we started a project called Toxic Soil Busters to clean up that lead. And there's an incredible plant, it's an African origin plant called Pelargonium or scented geranium, and it's a hyper accumulator. So, you can plant it, you acidify the soil, you plant it and it will suck the lead out and store the lead in its body. So, then you can dispose of that plant in a safe place. And over months or years, depending how bad your situation is, you have a healed soil. And that's so important because, you know, as black and brown folks, as poor folks, oftentimes we don't have access to prime bottom lands, soil. And so that doesn't mean actually giving up on the earth or giving up on self sufficiency. We have to be able to restore degraded and marginal lands.

CURWOOD: Sometimes the sciences, especially that love of nature and the environment and pursuing a career in those fields can seem, well, rather taboo for people of color. Why do you think that is? How do you think your book response to this?

PENNIMAN: It's heartbreaking for me, though, not surprising, because what it really speaks to is the depth of the inherited trauma from the centuries of slavery, sharecropping, and tenant farming to the point where just seeing a plant or seeing the soil is going to be a triggering experience for a lot of folks. Look at nature for really what it is, it's the scene of the crime. The nature is the scene of the crime, but she's not actually the crime. The way we try to address that is a couple of ways. One is to again, reach back beyond those 500 years to the 10,000 years of, of noble history on land and revive those stories and live into those stories. But it's also to confront the trauma head on.

CURWOOD: In your view, what have people of color lost by not having the farm as possible place of family refuge?

PENNIMAN: I was talking to an elder friend of mine, Donald Halfkenny, who is a civil rights veteran and was telling me stories about his time during Freedom Summer, registering people to vote in the south. And he was saying that they all stayed on black farms, all these activists, and they were protected. The farmers, to prevent Night Riders from coming and attacking the activists, would cut down trees and put barriers across the only road that got you out to these rural areas to slow down or to impede members of the Ku Klux Klan. All the meetings, if they you needed your shoes fixed, you needed a meal, it was the black farmers, and Mr. Halfkenny was saying that, you know, this was a clandestine network too, because then you'd see the same people that put you up in town the next day, and they act like they didn't know you because they also had to protect their own safety. And so I think about that a lot, that there really would be no civil rights movements without black farmers.

CURWOOD: And what do you think people of color lost when we lost contact with the land?

Farming While Black is not only a manual but a look into the history, sociology and science of farming. (Photo: Chelsea Green Publishing)

PENNIMAN: Certainly not all folks of color, right? Right now, about 85 percent of our food in this country is grown by brown skinned people who speak Spanish. And there's a whole history to why that is. But I would say, particularly for black folks, after the Great Migration, when six million of us fled the racial terrorism of the South, I think we did leave behind a little piece of ourselves. And, you know, it's a belief in West African cosmology that our ancestors exist below the earth and below the waters, and by having contact with the earth we've received their wisdom and guidance. And with the layers of pavement, and steel, and glass, and the skyscrapers, it’s harder to feel that contact, it's harder to have the generational wisdom. So, my personal belief is that many of us go around with this nagging sense of emptiness that we can't quite name. And when folks come to Soul Fire and get their feet back on the earth, what I hear time and again is, I'm remembering things I didn't know that I forgot.

When we own land, we also have power, we have autonomy, we have agency. When we depend on a system that hates us for our basic rights, our basic needs, we depend on a system that hates us for our food, our shelter, our meeting space, we're always in some way going to be beholden to that system. And so it limits our ability to resist. Folks, half joking, but maybe not, are always saying, well, thank God we have Soul Fire because when Armageddon comes, or when such and such, we have a place to go, and there will be food and there will be safety.

CURWOOD: Leah, how can farming and food be a healing and culturally restorative process for someone?

PENNIMAN: Hmm. You know, so often as black Americans we’re fed this myth that we don't have any culture, it was all lost in the transatlantic slave trade, we have no language, you know, we don't have a religion. So, we just need to try to emulate the ways of Europeans. And the better we get at it, you know, the higher status we gain. And in using food and land as tools, we reconnect to a different meter stick of success and belonging. And it's one that comes from our people. I mean, for example, just the other day, we're harvesting squash that we grew ourselves. Squash seed was a gift from the Taíno people to the enslaved black people of Haiti. In exchange for the seed that we brought over, hidden it in our braids, which was the cowpea, or the black-eyed pea. And so we took this squash seed as a gift from the native people and we grew it. And for many years, the ones who call themselves masters, the French did not even allow black people to eat this squash, we called it joumou, it was such a delicacy. It was a very tasty, and smooth, and sweet, so it was only prepared for white folks. After the successful revolution in 1804, we celebrated, our people celebrated by making the squash, the joumou soup, and every house made some. You go from house to house and sip it and taste all the different recipes. And that's been a tradition every January 1.

Soul Fire Farm offers trainings for People of Color to connect with the land and learn essential agricultural skills while also addressing the long and complicated history between people of color and nature. (Photo: Soul Fire Farm)

CURWOOD: How do you feel about organizations like your Soul Fire Farm? How do you feel they're doing it bridging this gap between people of color and reclaiming their birthright really?

PENNIMAN: How are we doing? I mean, I don't know if it's really for me to say because I feel like we're in service to our ancestors and to our community. And so everything we do is because we've been asked to do it. But I can say for sure that everyone who's gone through our program has talked in some way about this being what it would feel like if we were free, about this being a calling home to not settling anymore for being less than our full selves, for this being a healing repurposing. And we have, last time we did a survey, 86 percent of folks who graduated from our program have continued the work, so they're growing food, or they're organizing for food justice. And that means the world to me because I really want to be, not so much to expand and grow up as an organization, but really more like mycelium to grow out and figure out how to feed our alumni and other folks in the community who are doing projects that meet their local needs. And, you know, I think we're starting to see that, we're starting to see that resurgence.

CURWOOD: Leah Penniman’s book is called “Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land."

PENNIMAN: Thanks so much for having me.

Related links:

- Learn more about Soul Fire Farm

- The Farming While Black book website

- Leah Penniman speaking March 23, 2018 in Ithaca, NY: "Uprooting Racism in the Food System: A Legacy of Resistance"

- More about foreword Author Karen Washington

[MUSIC: Charles Mingus, “Jelly Roll” on ah um! by Charles Mingus, Not Now Records]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth.

ROBERT FROST: Something there is that doesn’t love a wall / that sends the frozen ground swell under it / And spills the upper boulders in the sun / and makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

CURWOOD: New England and its granite stone walls.

FROST: Good fences make good neighbors.

CURWOOD: That’s next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Joel Mabus, “Tiger Rag” on Parlor Guitar, by Nick La Rocca et al, Fossil Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org, iTunes and Google Play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. And you can find us on Instagram, @livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong clean energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth