November 30, 2018

Air Date: November 30, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Trump Climate Change Report

View the page for this story

The latest National Climate Assessment, assembled by 13 federal agencies, brings the most serious warning yet about the climate impacts that are already happening in the US, and the likely scenarios in decades to come. The Trump White House downplayed the dire findings as it continues to pursue rollbacks of climate protection regulations. Former President Obama’s Science and Technology Adviser John Holdren joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the report and the options for the new Democratic-majority House Of Representatives to push for climate action. (10:50)

Saving The Sumatran Rhino

View the page for this story

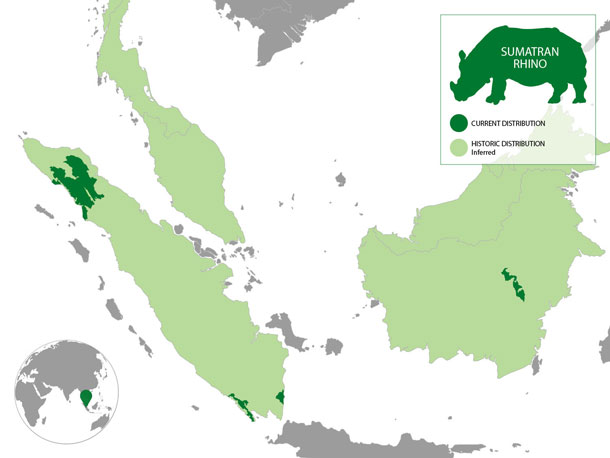

There are fewer than 80 Sumatran Rhinos left in the wild. They live in isolated island habitats, fragmented by agricultural development. Back in the 1980s scientists tried to breed captive rhinos to save the species, with limited success. But a new coalition is hoping to learn from past mistakes and renew the breeding program. Freelance journalist Jeremy Hance has reported about attempts to save the Sumatran Rhino from extinction, and talks with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb. (11:30)

Climate Dangers of Palm Oil

View the page for this story

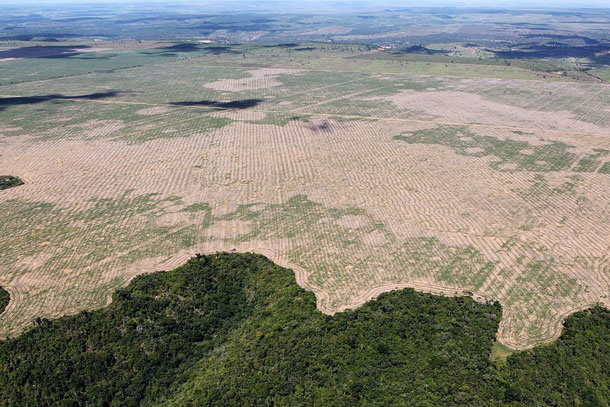

The palm oil industry is booming in Indonesia, resulting in the destruction of carbon-rich, tropical peatlands to make way for the cultivation of palms on a massive scale. And scientists say this crop has resulted in a net increase in carbon emissions, despite hopes for biodiesel to become a carbon-friendly replacement for fossil fuels. ProPublica Reporter Abrahm Lustgarten spoke with Host Steve Curwood about his investigative reporting into the hidden forces shaping the global demand for plant-based fuel. (08:40)

BirdNote®: Long-Lived Wisdom, The Albatross

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

In 1956, a pioneering bird biologist was banding Laysan Albatrosses on Midway Island. 46 years later, he rediscovered one of the same females, who at nearly 70 years of age has raised dozens of chicks and is still going strong today. BirdNote’s Mary McCann has the story on the long-lived albatross, aptly named Wisdom. (01:50)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood look at rising deforestation rates in the Amazon and its future under Brazil’s President-Elect Jair Bolsonaro. Plus, the duo discuss how sea level rise could promote a wave of gentrification in the US. Looking back in the history books, Peter reminds us to celebrate the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s upcoming 30th birthday. (03:30)

New England's Stone Walls

View the page for this story

New England’s first farmers of European descent found themselves plowing soil strewn with rocks left behind by glaciers. So, stone by stone, they stacked the rocks into waist-high walls. Some say these walls helped win the American Revolution, and they later inspired Robert Frost’s poem “Mending Wall.” Host Steve Curwood goes for a walk in the woods of New Hampshire with stone wall expert Robert Thorson, the author of Stone by Stone: The Magnificent History in New England’s Stone Walls. (10:40)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jeremy Hance, John Holdren, Abrahm Lustgarten, Robert Thorson

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Climate change is a growing wrecking ball for the US economy, says a new government report. There are more floods, drought, fires and storms, but little federal action.

HOLDREN: Today something like 70% of the American people agree that climate change is real, it's caused by humans, it's damaging; and believe the federal government should do more about it. But there is still not the sense of urgency, which would compel action.

CURWOOD: Also, demand for palm oil is driving tropical deforestation and massive carbon emissions.

LUSTGARTEN: Tropical peatland habitat in Indonesia and other places like Indonesia is a full 20 percent, 1/5 of all the carbon stock on the land on the planet. Ignoring that large chunk is really sort of a perilous game.

CURWOOD: And endangered species are also paying the price. We have that and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Trump Climate Change Report

A US Air National Guard C-130J drops fire retardant on the Thomas Fire that raged in Southern California in 2017. The latest National Climate Assessment found that climate change has already doubled the devastation from wildfires in the Southwest. (Photo: Staff Sgt. Nieko Carzis / U.S. Air National Guard, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. The day after Thanksgiving, the Trump Administration released the government’s 4th and latest National Climate Assessment mandated by Congress. It was the result of a deep dive into the impacts of climate disruption on the US ranging from public health, the land and infrastructure.

And it finds climate change could shrink the US economy and cost taxpayers around a half trillion dollars a year by the end of the century. Despite President Trump’s stated skepticism of climate change, unlike the Bush White House, the Trump White House did not try to water down the conclusions of this report. Harvard professor John Holdren was the chief science advisor to President Obama and oversaw the work behind the 4th climate assessment until President Trump came into office.

HOLDREN: This was a report in which 13 federal government agencies participated. All of the members of the US Global Change Research Program, which was created by Congress in 1990, and has existed and functioned effectively ever since. All 13 agencies contributed to this report with their top experts on climate change and its impacts. Many senior outside experts were also engaged. The thing was reviewed by the National Academy of Sciences. It was reviewed by all 13 agencies that participated and in none of those agency reviews were any changes requested. And again, I think that was a very conscious decision, and it's to be admired that they elected not to try to change the content.

CURWOOD: So, with the Trump administration continuing to roll back policies that address climate change, looking to roll back regulations such as the Clean Power Plan and the like, to what extent do you think that this report could affect those policies and perhaps change them a bit?

HOLDREN: Well, I don't think that any single report is going to overturn the Trump administration's inclination to minimize climate change and to try to back away from the regulations that we had had in place to deal with it. I think what's happening, rather, is that each additional report is a weakening of the administration's position, and ultimately it's going to have to topple. There's going to come a tipping point where the public's demand for action is going to become irresistible. I don't know exactly when that tipping point is going to happen. But what we're seeing is report after report, each one more dire than the last about what climate change is already doing and what it will do. And at the same time, those reports are reinforced by what people are experiencing.

The people in Texas and across the Southeast who have experienced unprecedented flooding, the people in the West who've experienced unprecedented wildfires, the people across the Southwest who've experienced enormous and very damaging droughts, the people in the Northeast who've experienced more heavy downpours and more flooding. What people are experiencing and what they're seeing on their TV screens and on their computer screens and on their iPads all are converging to send the message that this is real, it's damaging, it's going to keep getting worse until we take very serious action to address that, and ultimately those convergences and the fact that many of the solutions are actually getting cheaper, wind is getting cheaper, solar energy is getting cheaper, energy efficiency is getting cheaper. The fact that the incentives to act are getting bigger and the remedies are getting cheaper is ultimately going to produce a tipping point. This report was important. The immediate past report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in October of this year, looking at 1.5 degrees and two degrees and finding that 1.5 is much worse than the one degree Celsius that we have today. That two degree Celsius would be much worse than that. And that the only way to avoid going beyond two is to take very early and very aggressive action to reduce emissions. Then we have this new report laying out in unprecedented detail what the effects are in 10 different geographic regions of the United States across many different sectors of the economy. It just adds up and we are going to reach a tipping point.

CURWOOD: So, there has been report after report, each one seemingly more dire than the one before about the dark side of disrupting the planet’s climate; and yet not so much seems to have been done. Certainly not enough has been done to adequately meet the challenge. How do you feel about that?

The new Democratic-majority U.S. House of Representatives should prioritize passing carbon tax legislation and funding renewable energy technology, Prof. Holdren says. (Photo: Ron Cogswell, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

HOLDREN: Well, I feel terrible about it. I wrote my first articles about climate change in 1969. I think at that time, it was already becoming apparent that we were headed in a very dangerous direction. There were many others pointing out early on how dangerous the additions of greenhouse gases, of heat trapping gases to the atmosphere would become. We've known about this for a long time. Scientists have known about it for a long time. But there has been until recently, very little action. I mean, President Obama took more action, took more leadership in this domain than any president before had done, and now unfortunately, President Trump is doing his best to unravel, to roll back everything that President Obama put in place. Everything he put in place about emissions reductions, everything he put in place about adaptation, preparedness and resilience, Trump is trying to reverse, and we are losing time that we cannot afford to lose. This is really inexcusable what the Trump administration is doing.

When the Paris Agreements were reached in 2015, many people asked me, aren't you overjoyed that the Paris Agreements were so comprehensive and that 195 countries participated and agreed to their own contributions to reduce emissions? And I said, yes, I'm very, very happy, but I would have been happier if we had reached this point in 1990, 25 years earlier, when we already knew enough to embrace the kinds of measures which were finally agreed in Paris. We lost a quarter of a century and we lost it in substantial measure because of the voices of denial, the voices of waffling, the voices that said, well, we're not sure, maybe humans aren't doing it, maybe it won't do much harm, we have a lot of time to act, technology will get better so let's wait for better technology before we do anything. All of those voices together cost us 25 years and we can't make it up. We're now so far down the track toward truly disastrous climate change. And it's going to take Herculean efforts to avoid catastrophe. The good news is, I think, America's Pledge. Twenty-two states, hundreds of cities, hundreds of universities, more than 1,000 businesses, many civil society organizations, pledging that we're still in. That at all of these levels, in all these organizations across all these sectors, Americans are determined to take the measures needed to meet the commitments we made in Paris. The federal government may be out, but much of American society is still in and that at least is cause for some optimism.

CURWOOD: So, there's a new Democratic majority coming to the House in January. If they were to call you for advice, what would be the first thing that you would have the House do in terms of addressing climate disruption?

HOLDREN: Well, I think there are three major things that are needed. One is a price on carbon. I think the House should pass legislation that would create a substantial tax on carbon, which would escalate over time. The second thing that the House should do is they should pass a very large increase in funds for research and development and demonstration of advanced energy technologies, which down the road can help us reduce our emissions more deeply as is required.

The third thing that the Congress should do is pass a variety of measures making adaptation, preparedness and resilience mandatory across the government's departments and agencies. President Obama issued various executive orders that made it a requirement that every department and agency in the federal government had to take climate change adaptation, preparedness and resilience into account in every program, every project every budget; Trump has rolled all that back. Congress should put it back again.

Harvard Prof. John Holdren served as President Obama’s Science Advisor and Director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy during all eight years of Obama’s presidency. (Photo: courtesy of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University)

And another thing that Congress should do - which we, again, were doing with executive authority in the Obama administration - is boost efforts at climate change education. We need a public that understands more thoroughly than today's public does, how serious this problem is. Today, something like 70 percent of the American people agree that climate change is real. It's caused by humans. It's damaging. Something in the range of 70 to 80 percent believe the federal government should do more about it. But there is still not the sense of urgency which would compel action.

And we were working in the Obama administration with schools, we were working with colleges and universities. We were working with medical schools and nursing schools and schools of public health on the public health impacts of climate change, so that every student studying medicine, studying nursing, studying public health will have to take a course in the impacts of climate change on health. We were working with the National Park Service to provide materials on what climate change is doing to the national parks, so that when people go to the parks, they can actually see what's happening and understand what's happening. We should be doing all that and more to educate the public. And the Congress could insist that that needs to happen. Of course, there are many other things on the Congress’s agenda, a lot of other crazy stuff that this administration has been doing that needs to be stopped and reversed. But I certainly hope that the new Congress will give serious attention to the challenges of climate change, which are so big and coming so fast that really our only sensible option is to begin to take it much more seriously.

CURWOOD: Harvard professor John Holdren is a former Science Advisor to President Obama and Senior Advisor to the Woods Hole Research Center presidency. John, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

HOLDREN: It's been my pleasure. Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- The Fourth National Climate Assessment (Vol. II)

- The New York Times: “Trump Administration’s Strategy on Climate: Try to Bury Its Own Scientific Report”

- CNN: “Fact-checking the White House push back on climate assessment”

- Politico: “EPA chief: Trump administration may intervene in next climate study”

- About John Holdren

[MUSIC: Richard Stoltzman, “In the Morning” on New York Counterpoint, by Charles Ives, RCA]

CURWOOD: Coming up – How a US policy to encourage biodiesel is making climate change worse and destroying key habitats in Indonesia. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Richard Stoltzman, “In the Morning” on New York Counterpoint, by Charles Ives, RCA]

Saving The Sumatran Rhino

Sumatran Rhinos have a reddish hue with long shaggy hair. (Photo: World Wildlife Fund)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Indonesia’s Sumatran Rhino is one of the most critically endangered species in the world with less than 80 individuals left in the wild. Back in the 1980s scientists hatched a plan to save the Sumatran Rhino with a captive breeding program. Nearly everything that could go wrong did go wrong with that program, but now a coalition of conservation organizations, including National Geographic, is hoping to learn from early mistakes and start a new initiative to breed the Sumatran Rhino. Freelance writer Jeremy Hance wrote a series about the plan for the online magazine Mongabay, and he joins me now. Jeremy Hance, welcome back to Living on Earth.

HANCE: Thanks so much for having me today.

BASCOMB: So what got you started with Sumatran Rhino? Why do this series?

HANCE: I first met my first Sumatran Rhino in 2009; I was in Sabah in Borneo. And I went and met a rhino named Tam. And I was told before I met Tam that he was a very sweet and kind of like a giant cat. And I was kind of like, that's ridiculous. Rhinos have this reputation of being very aggressive and grumpy animals, but it's a misplaced reputation. And so I get there, and he is. He's like, he's rubbing up against the bars next to me. He's in this beautiful sanctuary in the rainforest. He's snorting at me, he's whistling at me, and spending time with this animal face to face, I just kind of fell in love and I've been following this story obsessively ever since.

BASCOMB: Well, what does it look like? How is it similar and dissimilar to its African cousins, the White rhino and the Black rhino?

HANCE: Sumatran rhinos are the oldest rhinos on earth. And they're the weirdest. They are the smallest, they have hair, and they're distant related to the Woolly Rhino. And they are the last Rhino in their particular genus. But I think what's really unique about it is just that has this, kind of this flank of reddish hair. Especially when it gets... it loves spending time in the mud. It's a rainforest animal. And then it's just, it's the most vocal of rhinos. And so it will sing to you, and the researchers compare the voices, the sounds that it makes to whales and dolphins.

BASCOMB: We actually have some sounds of the Sumatran Rhino. Let's have a listen.

[RHINO CALL]

BASCOMB: [LAUGHS] So, how many Sumatran Rhinos still exist in the world today? And why are they so critically endangered?

HANCE: Sure. So, the short answer is, no one actually knows for sure how many exist. There are some new numbers that just came out last week from a new program that's been launched, and the numbers were basically under 80. And the reason why they're so endangered is obviously they've been hunted for tens of thousands of years by humans. They're still being poached in the wild for their horns for sham medicine. They've also lost a lot of their habitat to deforestation, but at the most critical reason may just be that there are so few left that they're not mating in the wild and they're not having babies. So, basically, the population gets so small that even though there's some habitat left, they're just not enough there to really replenish the population.

BASCOMB: Right, and as the name indicates, they are from Sumatra in Indonesia, which is, you know, an archipelago of islands, so they're separated geographically. They can't find each other.

HANCE: Yeah.

BASCOMB: Well, so the story you wrote for Mongabay was really about this botched effort to try and save this Sumatran Rhino from extinction. What was the thinking back in the 80s about the best way to do that?

HANCE: Yeah, so in the 80s you had a really interesting development where several of the rhino experts got together in 1984 and they decided...they knew that the rhino was disappearing, they knew that there was a chance of extinction, even then, especially the ones who are really forward thinking and they said, you know, we need to get this animal in captivity. And at that time, they had already successfully done captivity for White rhinos, Black rhinos and Indian rhinos. So, they thought, oh, we can do this. And so they decided to catch a bunch of rhinos, and then put them in various facilities in Malaysia, and Indonesia, in the US and the UK. And what happened from that was a total disaster for about two decades, until they finally achieved some success.

BASCOMB: So, this was ostensibly a plan to breed captured rhinos and save the species, but plenty of them actually died while trying to capture them. And then even more died in captivity. What went wrong?

HANCE: Yeah, a lot of things went wrong. I mean, conservation is complicated, it's messy. You're dealing with animals that at the time no one knew anything about. So, what went wrong is there was mistakes made. Rhinos died in traps. People didn't know exactly how the best ways to catch them, or there was just mistakes...life happened. But then when we got them into captivity for a long time, people were feeding them as if they were a Black rhino or White rhino. They weren't feeding them correctly, so animals would just sort of slowly die in captivity because they weren't getting the right food. They weren't getting the right nutrients.

Fewer than 80 Sumatran Rhinos exist in the wild. They live in fragmented habitats on Indonesian islands of Borneo and Sumatra. (Photo: World Wildlife Fund)

There were also accidents, there was disease. And basically, it took scientists and zookeepers and conservationists about 10, 20 years to really figure out how to feed them right, how to care for them, what diseases were cropping up. And so you have this series of just tragedy, tragedy, tragedy. At the same time, in some ways, even worse, is the whole premise of this idea was to produce rhino babies, right? They were going to get a bunch of rhinos in captivity, they were going to mate like crazy, and they were going to have all these little baby rhinos running around. That didn't happen. They could not get the females to get pregnant. So, for the first 17 years, there was no babies. And then finally, a woman named Terry Roth at the Cincinnati Zoo was able to crack what was going on and was able to produce the first baby.

BASCOMB: And what did she learn? What did she do differently?

HANCE: Yeah, she's a scientist, she works at the Cincinnati Zoo. And she's still there. And she's a really incredible individual. But she basically she knew the history, she was brought into sort of take these two rhinos and get them, you know, last chance to do this. And she basically put the rhinos together. She knew that something was going on with the female ovulation. So, she would do ultrasounds all the time to see why the females weren't ovulating. And they just did this for 40 days. They put the male and the female together and watch what happened. And then she took measurements to see what was going on with the female. And eventually, what she discovered is that a Sumatran Rhino is actually an induced ovulator. And what that means is that there needs to be something to kick off the ovulation in a female, otherwise, they just don't ovulate. So, once she was able to crack that code, then all of a sudden, she was able to actually get pregnancies. And then through time, they were actually able to get a live baby on the ground in 2001.

BASCOMB: Wow, well, so from what I read your article, breeding pairs were captured in these so called doomed habitats. Those were areas that were slated for clear cutting, but after that, a lot of money went in to capturing them, moving them housing them, breeding them, taking care of them for years and years. Wouldn't have been cheaper and more effective just to protect their habitat?

HANCE: Yeah, and that debate was going on at the time, and there was a lot of very well known renowned scientists making that argument, and there was a lot of struggle. And basically, after the captive breeding program went so bad the debate shifted into we need to protect the habitat, we need to set more habitat aside. The problem that we've run into now is, there are so few left that we have basically one of two choices, we can either kind of watch them slowly go extinct, potentially - there might be one or two potential viable populations - or we can catch a few more rhinos and keep trying to keep this captive breeding alive. And neither option is great. It's not an easy situation, but I do think what the captive breeding population has done is they have proven they can do it, and they have given us a chance at ensuring that this animal can survive in the future. Even if it goes extinct in the wild. We might be able to still have Sumatran rhinos in captivity that could then maybe be released in the wild someday.

BASCOMB: So, now conservationists and biologists have a new plan to save Sumatran Rhino. Can you tell me about this Sumatran Rhino rescue project and how is this plan different from what they attempted before?

HANCE: The plan, Sumatran Rhino Rescue, is, it’s a consortium of various conservation groups. National Geographic in involved global wildlife conservation, the International Rhino Foundation, and their plan is to basically do what we did in the 1980s and 90s. Their plan is to go out and catch some more rhinos again. And the reason that they're doing this is because we have only nine rhinos in captivity, only two proven breeders. And we don't have enough genetics to really make sure that this captive population survives. And the rhino is still disappearing from the wild. So, the idea is, if we can go into the field, capture a few healthy females especially, maybe a couple more males, we can supplement the captive breeding program and really make that a success and then ensure that the species doesn't go extinct.

BASCOMB: Well, I have to play devil's advocate just a little bit here. Several millions of dollars...I can't say how many millions of dollars has been spent trying to save the Sumatran rhino. And I mean, there's only less than 80 individuals, they seem somewhat doomed. Why not instead invest that money into anti-poaching units and conservation units and things for the 22,000 African rhinos that are left that maybe have a better shot at avoiding extinction?

HANCE: Sure, and I think so I would say a couple of different things to that. The African rhinos, both the White and Black rhino have a good established breeding population in captivity already. So, if we did happen to lose them, which I don't think we're anywhere close to losing the White rhino right now even as bad as a poaching is and that is a human tragedy and a tragedy on a large scale. So, I'm not trying to diminish that.

A baby Sumatran Rhino. Sumatran Rhinos are smaller than their African cousins with long shaggy hair. (Photo: Cincinnati Zoo)

The other thing I would say is that the Sumatran rhino represents this distinct genus, this wonderfully weird throwback that a lot of people have probably never even. Look it up. Look at this animal. It's weird, it's wonderful, it's googly-eyed. I think that every species in our planet that we have somehow inherited deserves a chance, and I think that the rhino probably plays an ecological role that we don't even realize in the rainforest. Beyond all of that we have a moral obligation, we have a moral obligation not to allow species to go extinct if we have any chance of saving them. And a few million dollars here or there isn't that much money in the grand scheme of things to save a species that has somehow survived tens of thousands of years of humans hunting, and now we have a group of humans who are actually trying to prevent its extinction. So, I think the moral obligation speaks wider than pretty much any other argument I can give.

BASCOMB: Well, how confident are you that this new effort will be any more successful?

HANCE: I'm cautiously optimistic. I'm cautiously optimistic because I know the individuals involved and I know what they're striving for. I wish that this had happened 10 years ago. I wish that we had more rhinos, in captivity. You can do all the wishes in the world, but I wish that the situation was somewhat different. But I do think that the challenges are huge. And another reason I guess I would say, I'm cautiously optimistic is that we've done this before. The European bison went extinct in the wild, down to 12 animals, and they brought it back and now there's 4,000 in Europe. So, we can do this. This is not impossible. We just need the money, the support and collaboration, I think. Things are going to go wrong. It's not going to go perfect. I'm sure that there will still be tragedies to go. But I do think that having met some of these baby animals, when I visited the sanctuary in Indonesia, and met the people who take care of them every day. That's what makes me optimistic.

BASCOMB: Jeremy Hance is a freelance reporter and senior correspondent for Mongabay. Thanks so much for talking with me Jeremy.

HANCE: Thank you so much for having me. You have a good day.

Related links:

- Mongabay Series on the Sumatran Rhino

- National Geographic | "First wild Sumatran rhino captured in urgent bid to save species"

[MUSIC: Waves of Sumatra, “Shakudawning” Half Loop Records 2015]

Climate Dangers of Palm Oil

A truck carries freshly-harvested palm fruit through a plantation in Indonesia. (Photo: Ashley Gilbertson, special to ProPublica)

CURWOOD: One of the biggest drivers of extinction for the Sumatran Rhino is habitat loss, namely the conversion of tropical forest land into palm oil plantations. And demand for palm oil is booming. It’s a common ingredient found in a wide variety of foods and household products, from cookies, bread, and chocolate to soap and shampoo. And, it turns out, a US mandate for biofuels has an unintended consequence of causing a spike in demand for palm oil and thus even more deforestation in Indonesia. Here to explain is ProPublica Reporter Abrahm Lustgarten. Welcome back to Living on Earth!

LUSTGARTEN: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Yeah, so talk to me about the act of Congress that was signed in 2007 by President Bush that transformed the demand for biofuel in the United States. What exactly was this law and how does it relate to the palm oil industry in Indonesia?

LUSTGARTEN: Yes, so in 2007, Congress passed the Energy Independence and Security Act, and it was meant to decrease the United States reliance on petroleum on oil. And it did a couple of things for the environment. It increased the fuel efficiency standards of automobiles, but it also mandated that we use biofuels, that we replace a certain amount of gasoline with ethanol from corn and sugar and replace a certain amount of diesel with vegetable oils from namely from soybean oil. And this was supposed to help American farmers. What ended up happening is that Indonesian farmers who grow palm oil also contributed to the biodiesel supply, but also as the soybean oil supplies around the world were used up to support biodiesel in the United States, the food industry which uses vegetable oils for lots of different purposes, went to palm oil instead. And basically palm oil demand increased dramatically as the soybean oil on the market disappeared and was used for biodiesel.

CURWOOD: Explain for our listeners what a plot of land looks like after it's been cleared for palm oil tree plantations, the sorts of things that you saw.

A Dayak elder, part of a group of native people in Borneo, works to control a slash-and-burn fire used to clear land in West Kalimantan. This fall, authorities instituted a shoot-to-kill order for anyone using slash-and-burn techniques to clear land. (Photo: Ashley Gilbertson, special to ProPublica)

LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, I mean it's total devastation. You take a forest and what looks like greenery and natural soil and you don't really see the ground when there's a forest on it. It’s laid bare in neat rows that can stretch on for half to a full mile of basically long puddles. In between the puddles, where you might see like rows of a soil in a tilled farm in the United States, you see mounds of mud separated from just long streams of exposed water and that water is basically groundwater that comes up through the peatland soil. It's a marsh, basically. It's just a huge expanse of brown mud.

CURWOOD: If there's a lot of water there that's covering the peat, obviously when those trees are cut and the peat starts to dry out, that must release enormous amounts of carbon?

LUSTGARTEN: Yes. So, the peatland is a huge carbon bank, and as soon as it's cleared it begins to release its carbon, and as it dries out at that release increases, and if it's burned, which often happens after it's dried out, then that release increases exponentially. One of the pieces of data that we reported on our story is that the clearing of the peatland so far in Indonesia was the equivalent of operating 70 new coal fired power plants. It's a regular source of emissions and it lasts for many months, many years, even a century depending on the piece of land and the exact habitat that we're talking about.

CURWOOD: How do these methods compare to burning fossil fuels in terms of the carbon map?

LUSTGARTEN: When you look at palm oil used for biodiesel and analysis of that life cycle done, whether by U.S. researchers or European researchers, they unanimously agree that it's worse than burning petroleum diesel. So, the debate is really about how much worse and those estimates range from three times to five times worse. But when you calculate in that constant emissions source from exposed or burned peatland, it's significantly worse than just burning oil.

CURWOOD: Now, what kind of calculations have been done on the impact that the palm oil industry in Indonesia has had on native plants and animals?

LUSTGARTEN: So, there's enormous ecological and biodiversity impacts to palm oil. I mean, you're taking one of the most robust and diverse natural environments on the planet and replacing it with a monoculture crop, a single crop that is expansive and basically displaces everything that used to be there. And then, you're using fertilizer and chemicals on top of that to support that crop and it's really devastating. So there's many, many species that are impacted, but among them famously is the orangutan, whose habitat is right in the middle of the palm oil plantation areas that we were in, in Borneo. And that's the most vivid example of the loss of species.

The monoculture palm oil crop has encroached upon the habitats of many native plants and animals, most notably the orangutans. (Photo: Ashley Gilbertson, special to ProPublica)

CURWOOD: When you talk to some of the people there how did they tell you they felt about this burgeoning industry and the effect that it's had on their landscape?

LUSTGARTEN: When you talk to rural people, their response is overwhelmingly negative. There was a hope that the industry would bring economic change, and everybody wants to improve their livelihood to some degree. But for the most part, everyone felt taken advantage of by the companies that come in with immense power. They negotiate in air quotes. So, what you have is an environment that used to support what the people needed off of that land for free, whether it was clean water, or vegetables, or crops or whatever, and you replace it with an economy and they might have some employment, but then they need to use all of the money they earned through that employment to purchase those same resources that the land used to provide for them. And people are realizing that this has not been a bargain that's worked out to their advantage.

CURWOOD: But now how do they respond in the city?

LUSTGARTEN: Well, in the city, there's clearly a more nuanced reaction. I mean, the wealth that palm oil and resource industries have brought to Indonesia is enormous. And so, if you are employed in one of those large corporations or benefit tangentially in some way, then palm oil is really the money machine. So, there is an appreciation I found for the environmental concerns, but not necessarily that direct in personal impact for how it's changed the household or people's specific families.

CURWOOD: And tell me about Indonesia's own perspective on this in terms of its commitments under the Paris Climate accord.

LUSTGARTEN: So, Indonesia also has carbon reduction commitments that it's made under Paris. And at least by lip service, they're concerned about their own climate emissions and about climate change in general. Ironically, they're pushing their own biofuel mandates, making themselves their largest customer for palm oil based biodiesel. And they argue that that is going to be one of the strategies for meeting their commitments in Paris to cut their carbon emissions, so they don't accept the measures that say that palm based biodiesel is worse for the climate worse for carbon output than just burning petroleum. So, they're on a path that's going to lead in the opposite direction despite their professed concern for the climate that’s shared with us.

CURWOOD: So, what has the United States done to answer for the role that we have played in the accelerated destruction of Indonesia's habitats and the accompanying rising costs?

Abrahm Lustgarten is a senior environmental reporter with ProPublica. (Photo: ProPublica)

LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, I mean, very little. The United States has kept its distance. With regards to palm oil, specifically, the US is a large market for palm oil used for the food industry. For biofuels, palm oil is not actually eligible for the US biodiesel mandate. So the impact is indirect, and legislators, industry groups, even to some extent, environmental groups use that distance as kind of an excuse to say things like, “well, you know, the biodiesel for the United States is coming from our soy fields, or it's coming from South America. And so, if South America then draws its palm oil from Indonesia indirectly - which is one of the phenomenons that happens - that's their responsibility and not ours.” And so there's a sort of a disempowering or lack of responsibility assumed by Americans that I talk with because they don't see this as a direct effect, it's more of a ripple effect. And that responsibility is often passed off.

CURWOOD: There's just one planet with one atmosphere that's getting all this carbon put in it. What's the risks to all of us from this carbon that's coming off of the palm oil plantations?

LUSTGARTEN: The risk is enormous. I mean, typically, I'll report on a on a problem that has to do with, say, a coal plant or two, which is really kind of a drop in the global bucket. Here for the first time, and I was looking at an issue, tropical peatland habitat in Indonesia and other places like Indonesia that is a full 20 percent, one-fifth, of all the carbon stock on the land on the planet. And when you have the United Nations and other institutions warning that we have about a decade left to get control over our global emissions patterns, our global emissions rates of increase, looking at or ignoring that large chunk that one fifth of planetary supply of carbon that is happening now in Indonesia is really sort of a perilous game.

CURWOOD: Abrahm Lustgarten is a senior reporter at ProPublica. Thanks for taking the time with us today, Abrahm.

LUSTGARTEN: Thank you for your interest. I appreciate it.

Related links:

- Read Abrahm’s full feature story here

- Summary of the Energy Independence and Security Act

- World Resources Institute: The latest Science on Tropical Forests And Climate Change

- Abrahm Lustgarten ProPublica Page

BirdNote®: Long-Lived Wisdom, The Albatross

Wisdom with one of her chicks. As of 2018, she is believed to have hatched as many as 35, despite the fact her 67 years of age makes her quite old for her species. (Photo: Kiah Walker, USFWS, CC)

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BASCOMB: November marks the start of the courtship season for the Laysan

albatross. These seafaring birds can soar hundreds of miles per day with barely

a wingbeat, and they mate for life. BirdNote®’s Mary McCann tells us about an enduring matriarch of the species.

[Laysan Albatross calls]

MCCANN: In 1956, pioneering bird biologist Chandler Robbins was fastening ID bands to the legs of Laysan Albatrosses. His work took place on tiny Midway Island way out in the Pacific Ocean, where roughly one million albatrosses nest each year.

Little did Robbins suspect he would re-find, in 2002, one of the same females he had banded 46 years earlier! In honor of her unprecedented history, another researcher named the long-lived albatross “Wisdom.”

Since then, scientists have been checking in on Wisdom. And each year she has not only nested but laid eggs and raised chicks successfully! She’s set records for endurance and longevity — as well as fertility.

Wisdom is the oldest confirmed wild bird in the world, and since she was tagged in 1956, she is also the world’s oldest banded bird. (Photo: Naomi Blinick, USFWS, CC)

[Laysan Albatross calls]

And it must not have been easy for her, with all the plastic rubbish, fishing lines, and nets that plague these elegant seabirds. At nearly 70, Wisdom is the oldest known banded bird in the wild. It’s not known with certainty how many years an albatross might live. One thing we do know for certain: Wisdom has fans all over the world, rooting for her to return to Midway this November.

I’m Mary McCann.

Written by Bob Sundstrom. Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. BirdNote’s theme composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler. Producer: John Kessler. Managing Producer: Jason Saul. Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

© 2018 Tune In to Nature.org, November 2018. Narrator: Mary McCann

References:

https://www.google.com/amp/s/relay.nationalgeographic.com/proxy/distribution/public/amp/2018/01/birds-animals-oceans-parents-albatross

https://www.fws.gov/refuge/Midway_Atoll/wildlife_and_habitat/Wisdom_Profile.html

https://www.birdnote.org/show/long-lived-wisdom-albatross

Related links:

- Learn more on the BirdNote website

- Read Wisdom the Albatross’ profile

- Wisdom has hatched a chick every year since 2006, most recently in early 2018

[MUSIC: Snore Kirk, “Pastorale” on Stunt Records 2017, by S.Kirk, Sundance Music]

CURWOOD: Coming up- The stone walls of New England, where they say “Good fences make good neighbors.” That’s ahead here on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Snore Kirk, “Pastorale” on Stunt Records 2017, by S.Kirk, Sundance Music]

Beyond The Headlines

The Amazon Rainforest, a haven for multitudes of diverse species, has been subjected to aggressive deforestation for decades. (Photo: Ibama, Wikimedia Commons CC)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Let’s take a look now beyond the headlines now with Peter Dykstra. Peter’s an editor for Environmental Health News, that’s EHN dot org and Daily Climate dot org and is on the line from Atlanta. Hey Peter, how are you doing?

DYKSTRA: Doing alright Steve, I want to talk about the Amazon rush since we're getting on toward Christmas time. But no, we're not talking about Amazon.com. We're talking about the original, only true Amazon, the world's biggest rain forest. And in the past year, from August of 2017 to July of 2018, there was an alarming rate of deforestation in the Amazon about 3000 square miles. To put that into perspective, that's about three times the size of the state of Rhode Island, or about a billion trees.

US coastal cities like New York City are highly susceptible to complications due to sea level rise. (Photo: JJ, Flickr CC)

CURWOOD: And a number of years ago, deforestation was decreasing in the Amazon. But this is turned around huh?

DYKSTRA: It was but it seems to be having backup in the coming years. It may have upwards dramatically even more. And of course, Jair Bolsonaro, the president-elect of Brazil as a campaign promise said he wanted to turn the Amazon into an even bigger agricultural juggernaut, which of course means removing all of those annoying trees.

CURWOOD: Oh, boy. Hey, so what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: A little speculation about how sea level rise could cause a big wave of gentrification in the United States…

CURWOOD: Gentrification from sea level rise? What are you talking about?

DYKSTRA: Well, think of the coastal communities that are going to be displaced if all of the projections about sea level rise hold true. You've got poor communities like Liberty City in Miami, neighborhoods in Brooklyn, small towns along the Louisiana coast, but you've also got filthy rich communities with million or multimillion dollar homes around New York City, the Jersey Shore, the New England coast and of course down in Florida, beautiful Mar a Lago.

CURWOOD: So you're saying that when the waters rise, those rich people are going to be competing with the poor people for new places to be?

DYKSTRA: Right. And the real estate market if it's rich people versus poor people, guess who gets the best land. So you'll have inland gentrification as everyone moves away from the coastline. Again, it's only speculation, there's no data to back it up. But it's something to think about. And something that prepared before as one more unintended consequence of sea level rise and climate change.

CURWOOD: And it's not just sea level rise, Peter; what about places that have really been blasted out by these intense forest fires? Those folks are looking for new homes as well.

DYKSTRA: That's right.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was founded 30 years ago. (Photo: IPCC)

CURWOOD: Hey, what do you have from the history vault for us this week?

DYKSTRA: We have a 30th birthday party, December 6, 1988, the birth of the IPCC, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the UN body of scientists, that's considered to be the gold standard of climate science

CURWOOD: 30 years old? Boy, that happens fast.

DYKSTRA: Right, 30 years old, entering middle age. Remember, of course, that in 2007 the IPCC was 19 years old. The IPCC was a teenager when they shared the Nobel Peace Prize with Al Gore. They've been so effective that climate deniers have set up a shadow IPCC called the Non-governmental International Panel on Climate Change, or N-I-P-C-C to try and bamboozle a few more people into thinking the climate change isn't the problem that scientists say it is.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Peter’s an editor with environmental health news, that's ehn.org and daily climate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right Steve thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at our website loe.org.

Related links:

- BBC | “Amazon rainforest deforestation 'worst in 10 years', says Brazil”

- WBUR | “What the Brazilian Presidential Election Means for the Amazon Rainforest”

- Our previous segment: “Brazil to Increase Amazon Deforestation”

- Huffington Post | “'Climate Gentrification' Will Deepen Urban Inequality”

- Learn More About the IPCC

[MUSIC: The Blue Dahlia, “I See Trees Differently” on La Tradition Americaine, self-published]

New England's Stone Walls

Many of New England’s stone walls, like this one in New Hampshire, are going back to nature as they fall into disrepair and become overgrown with moss. (Photo: mwms1916, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: The colonists in New England faced an uphill battle in turning the region’s vast forests into farmland. They had to fell massive trees and contend with rocks strewn throughout the soil they aimed to plow. So, stone by stone, they stacked the rocks left over from glaciers into waist-high walls. Each year frost heaves pushed still more stones to the surface, which some of those early farmers said was the work of the devil.

Generations later, farmers returned time and again to repair the walls as the years went by. That’s the subject of Robert Frost’s famous poem, The Mending Wall, read here by the poet himself.

FROST: Mending Wall

Something there is that doesn't love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun;

And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

The work of hunters is another thing:

I have come after them and made repair

Where they have left not one stone on a stone,

But they would have the rabbit out of hiding,

To please the yelping dogs. The gaps I mean,

No one has seen them made or heard them made,

But at spring mending-time we find them there.

I let my neighbour know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

And some are loaves and some so nearly balls

We have to use a spell to make them balance:

"Stay where you are until our backs are turned!"

We wear our fingers rough with handling them.

Oh, just another kind of out-door game,

One on a side. It comes to little more:

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, "Good fences make good neighbours."

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

"Why do they make good neighbours? Isn't it

Where there are cows? But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I'd ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offence.

Something there is that doesn't love a wall,

That wants it down." I could say "Elves" to him,

But it's not elves exactly, and I'd rather

He said it for himself. I see him there

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me,

Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not go behind his father's saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, "Good fences make good neighbours."

A New Hampshire stone wall in winter. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: Those stone walls of Robert Frost’s verse still exist in Southern New Hampshire, as do thousands like it across New England. Made mostly of granite, these walls serve as windows into the geological and cultural history of the region. I went for a walk through an old farmstead with a stone wall expert to learn more.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: So, we're here in Nottingham, New Hampshire, at a 1755 farmhouse. It's surrounded by stone walls, and we're joined now by Robert Thorson. He's a professor of geology at the University of Connecticut. And he's author of “Stone by Stone: The Magnificent History in New England's Stone Walls”. Welcome to Living on Earth, Professor.

THORSON: Thank you. It's a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: So, how did you first get involved studying stones?

THORSON: Well, I moved here from Alaska, and I had grown up in the sort of Scandinavian Midwestern upper Midwest heritage where you don't see any stone walls whatsoever and I moved here from Alaska in 1984. And I thought, well, I'm hired as a landscape archaeologist and a geologist and a scientist to teach. And I thought, I better go get myself a look at stone walls. And so I went to the Natchaug State forest, which is nearby in eastern Connecticut where I was working. And I just started walking a traverse. And I was going up over one after another, and another and another stone walls, and it just struck me that day. What are these things? Why are they the size they are, the color they are, the mass they are, the continuity they are, the pattern they are... all those questions that a trained scientists would ask about them.

CURWOOD: So, stone walls are all over the region. Who made these walls?

THORSON: If you're talking about the abandoned field farm landscape of the 19th and 18th century, then almost entirely, it's the people who own the land and were using money from the land to do things. If you're talking about the Gilded Age or 1920s or Edwardian or even late Victorian, when you get past the zenith of New England's agriculture, then most of the walls are being built by immigrant work parties for very low pay, but the money came from somewhere else. And so you end up with a nice, tidy, long, uniform degree of construction that an architect might recognize. The walls that I like are the ones built by the people on the land, because there's an ecological component to them, a human ecological component.

Robert Frost (1874 – 1963) was a prolific American poet whose work included, “The Road Not Taken,” “Fire And Ice,” and “Mending Wall.” (Photo: Walter Albertin, Wikimedia Commons via U.S. Library of Congress)

CURWOOD: Let's go up the wall a little further, because I want to ask you about the ecology of what's in these walls today.

[SOUNDS OF FOOTSTEPS]

CURWOOD: So, many of these stone walls obviously were abandoned. This farm stopped farming livestock probably a century and a half ago. But you say that these are important parts of our ecosystem. What makes them so important in the ecosystem?

THORSON: Well, if you look at the stone wall right in front of us, you don't see any surface moisture, and you never will, unless it's raining or you're getting snow melt. These are very, very dry. They're effectively deserts. They're hollow, open spaces that animals can live that don't exist on the woodland floor. It's also a corridor. If you wanted to move along your territory and you were a fox, or you were a squirrel, or you were a cat, a bobcat or a fisher cat, you could cruise along the top of the wall and see more. You would be more exposed if you were a predator. If you were prey, you'd likely scurry along beneath the edge of the wall, and you get cover. So, as boundaries, as corridors, and as habitat, stone walls have a life all their own.

CURWOOD: And the geologic story here?

THORSON: Well, if you accept that human beings are geologic agents - which I do, being the strongest one - then they're part of that geologic story. If you were to just say, OK, what happened here since glaciation, we're about it. I mean, glaciation and then human activity, those are the two dominant events that have happened here on the landscape to shape and change the landscape. It's not to say that other people didn't live here for a long time, but these are the main shapers, and one is glacial in origin, climatically driven, and one is human in origin, economically driven.

CURWOOD: Thor, talk to me about the famous stone walls here in New England.

THORSON: I think the most famous one is Robert Frost’s Mending Wall, because people in Iowa know about that wall. People in Florida know about that wall, and it's one of New England's real treasures, that poem. And I've been to Derry a number of times, and I've talked there and explored and investigated the mending wall. It turns out the Mending Wall is a combination of two different walls. That poem was written when Frost was in England. It was one of his earliest ones and he's writing it from memory. And he garbled together two things, whether intentionally or not, that are really important to the New England psyche. One of the ideas, the maintenance, structure, order, you know, keeping stone on stone, mending the wall, and the other, of course, is territorialism, the fences that we erect between ourselves in our communities and otherwise. And he really dwells nicely on both of those. The Mending Wall, the poem, has both the boundary wall and the precarious stones as round as balls are loaves, but the actual walls on that property are very distinct. One is a boundary and one is a place where you can hardly stack a stone, and they don't map on top of each other.

CURWOOD: Philosophically, what do you think if his point that there's something that doesn't like a wall?

THORSON: That something is all of nature itself that doesn't like a wall, because a wall is created with intent by human beings. For whatever reason, it's going to come down, and to me, that's nice. I love the old, abandoned, lichen-crusted closed canopy forested walls in the age of the Anthropocene because they tell us that in some places, the Anthropocene impact is already being re-healed. And the wildness seeking person in me likes seeing that.

Robert Thorson (left) and Host Steve Curwood examine a rock from a wall in New Hampshire. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: So some would say that stone walls helped win the American Revolution. Why would they say that?

THORSON: The number one reason that they would say that would be because the colonists, the ragtag Minutemen, used the walls for cover, and they were very hard to pick off by the British marching in columns down the road. On a deeper level, you could argue that the walls are expedient parts of the farms that gave the beef and the butter and the bacon and the bread that fed those armies. We know that armies don't march on an empty stomach. Also, I think there's a territorial boundary element. I think that just seeing a stone wall, makes you feel more secure, it makes you feel enclosed. It makes you feel contained. It makes you feel separate. So, you could say that, at a psychological bedrock level, they helped with the idea of separateness.

CURWOOD: Robert Thorson is a professor of geology at the University of Connecticut. Thor, thanks so much for taking the time with us.

THORSON: It's been a pleasure. What could be nicer than being in the woods with surrounded by stone walls?

Related links:

- Stone by Stone: The Magnificent History in New England’s Stone Walls

- “Mending Wall” by Robert Frost

- About Robert Thorson

[MUSIC: Szymon Nehring, “Etude in A Flat Major Op. 25 No. 1” by Chopin, The Fryderyk Chopin Institute, Polish Television TVP]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

And we say goodbye this week to Sarah Rappaport. Thanks for all your hard work, Sarah! You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong clean energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth