December 28, 2018

Air Date: December 28, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Rebuilding Puerto Rico’s Battered Farms

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Despite being a lush tropical island, Puerto Rico imports nearly all of its food. Hurricane Maria brought road closures and shuttered grocery stores, leaving many Puerto Ricans with no choice but to skip meals and live on shelf stable and canned food for weeks and months. But as Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports, volunteers and farmers are working together to rebuild Puerto Rico’s small and devastated farming sector. (11:43)

“Pa’lante”: Puerto Rican Resilience After Maria

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

On September 20, 2017 Hurricane Maria made landfall on Puerto Rico, taking roughly 3,000 lives. Most the morbidity came not from the wind and rain of the hurricane itself, but rather from the isolation that followed. Cut off from the outside world, many people died from such conditions as treatable infections, unsafe water and accidental electrocution. But as Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports, some communities are looking at Hurricane Maria as a call to organize and become more resilient for future storms. (18:53)

Volunteers Test Drinking Water in Puerto Rico

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

When Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico, water utilities were shut down, making access to safe drinking water one of the most pressing issues across the island. Faced with water-borne diseases, a citizen science group in Rincón, Puerto Rico rallied to help test drinking water sources. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports. (08:02)

.jpg)

Repairing Puerto Rico’s Corals

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Roughly 10 percent of Puerto Rico’s corals were broken and damaged by Hurricane Maria in 2017. Corals are a first line of defense against storm surges and a critical habitat for juvenile fish but face an uphill battle against warming seas, ocean acidification and ship groundings. As Host Bobby Bascomb reports, Puerto Ricans are finding ways to give corals a fighting chance by reattaching healthy fragments. (08:05)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bobby Bascomb

REPORTER: Bobby Bascomb

BASCOMB: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb, in for Steve Curwood. We’re taking a look back a series we featured earlier this year about recovery on Puerto Rico following Hurricane Maria.

NIEVES: It was like all the movies that you’ve seen of Armageddon, of destruction, of the end of days, it was like - this is done. And the fact that the communication collapsed meant that also we couldn’t hear the government, but we couldn’t hear each other. All we had was the people next to us.

BASCOMB: Many say the silver lining from Hurricane Maria is a renewed sense of community and self-empowerment.

CARLO: I'm working seven days a week. But I'm doing it with a smile on my face, because I know it's for the good of everything. And I know this is my journey in life and this is what we're going to be doing. No matter how many hurricanes come, we’ll still bounce back. Nothing is going to keep me out. Not even a category 5 hurricane.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Rebuilding Puerto Rico’s Battered Farms

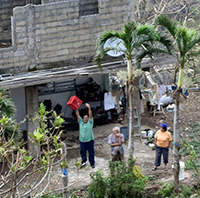

Farmers Domingo and Nilsa Romano are grateful for the physical and emotional support of the volunteers with the NGO El Departamento de la Comida. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb, in for Steve Curwood.

On September 20, 2017, Hurricane Maria made landfall on Puerto Rico with winds topping 155 miles per hour. The storm devastated nearly every aspect of life on the island – water, food, infrastructure, and of course the natural environment. Nine months after the storm, in June of 2018, I took a trip to Puerto Rico and reported a series of stories about recovery on the island.

In the next hour we’ll take a look back at those stories, starting with the farming sector. Even before hurricane Maria uprooted trees and people, Puerto Rico imported roughly 85% of its food. After the storm that number shot up to about 95% imported food -- if you could get it. Many people were forced to skip meals and eat shelf-stable and canned food for months.

[MARKET SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Nine months after the storm one of the only places to find locally grown food on the island is farmer’s markets like the Saturday market in Rincon on Puerto Rico’s west coast.

MAN: Do you have kale?

CARLO: Yes, we have kale. You want baby kale or dinosaur kale?

MAN: Dinosaur kale? How’s that?

BASCOMB: Sonia Carlo’s nearby farm is slowly recovering from the storm. Today she’s brought pineapple, papaya, mushrooms, and the kale she’s explaining to a customer.

The Puerto Rican and American flags painted on the corner of a building in Rincon, Puerto Rico. The Puerto Rican dependence on imported food can be attributed, in part, to US economic incentives. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CARLO: …. They’re two for five, so if you want both of them…

MAN: I like kale. What’s a single go for?

CARLO: Three, or two for five.

MAN: You got change?

CARLO: Yeah.

MAN: I’ll take…I’ll take both. Why not?

CARLO: Alright. One and one? Thank you.

BASCOMB: Sonia’s bright smile makes her a natural salesperson.

CARLO: It's a good time to be at the market right now.

BASCOMB: Sonia says things are just starting to turn around for her family and the farm. They are finally harvesting again and her farm to table restaurant, Sana, opened just a few weeks ago. But Hurricane Maria was devastating for them. The storm destroyed her home. She had to send her 3 children to Florida to live with family while she and her husband, living in their car, rebuilt the battered farm.

CARLO: We got really trashed. All of our production for years of tropical trees like mango trees and passionfruit trees, they all died and they all were blown away. We had trees that were a hundred years old and you know, totally perished. Since the hurricane was a cyclone, it brought some salt water and some sand with it, so everything that was in its path, it looks like you threw herbicide.

BASCOMB: Across the island tall fruit trees were the most heavily damaged food crop. Root vegetables that could hide underground did ok. Ground plants like pineapples were among the first to recover, and fast growing vegetables like salad greens were easy enough. After the hurricane, visitors came to Puerto Rico with their suitcases full of seeds to donate to farmers. Sonia says they actually could have started growing again relatively quickly.

CARLO: But since we didn't have any electricity, we couldn't pump water out and we didn't have any gas, so we were unable to grow food because we don't have gas to pull out the water from the water pump. You know, it was just - you know trying to scrape up anything. Waiting ten hours for gas, just to grow food. It was very uncertain.

[SFX LATIN MUSIC IN GROCERY STORE]

BASCOMB: Grocery stores are open again on the island. But visit a grocery store on Puerto Rico and you’ll be hard pressed to find anything supplied by local farmers. I went shopping at an Amigo chain grocery store, which is owned by Walmart.

[SFX GROCERY STORE SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Let’s see, there’s pineapple from Costa Rica, coconuts from the Dominican Republic. Honeydew melon from Guatemala. Over here there’s more watermelon, chopped up – [gasp]. Aha! I found some watermelon from Puerto Rico. These are watermelon already cut up into pieces. The whole watermelon came from someplace else.

[GROCERY SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: To understand why this lush tropical island with year round sunshine and rain imports nearly all of its food, you need to go back to the 1940s and a US initiative called Operation Bootstrap.

MARICHAL: With the colonization of the US there was a movement to get people out of their farms and into the cities.

El Departamento de la Comida volunteers travel to farms in a bus, locally known as a guagua, which carries all the equipment they will need for their work. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Adnelly Marichal is the documentarian for the Resilience Fund in Puerto Rico. She says Operation Bootstrap transformed Puerto Rico from a largely agrarian economy to one based on manufacturing and tourism. They did that with a patchwork of government tax incentives and access to US markets. The farming that remained was not on the household level but on a larger, industrial scale.

MARICHAL: Now suddenly, it’s about making money so therefore you need to grow things like sugar and coffee. And that’s great, but those are not things that people can eat.

BASCOMB: And the food that is imported to Puerto Rico is on average 20% more expensive than in the US. That can be attributed at least in part to the Jones Act of 1920, which says any item imported to Puerto Rico must be carried on a US vessel. So, if Puerto Rico wants to import let’s say tomatoes from its neighbor, the Dominican Republic, those tomatoes must first go to the US mainland more than 800 miles away. They get put on a US boat, and then travel back those same 800 plus miles to Puerto Rico.

MARICHAL: So, it both makes the food more expensive and less nutritious by the time it gets here; it’s been on a boat much longer than it has to be. It just creates a much longer timeline.

Volunteers eating lunch before they get back to work fixing the Romano’s roof. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: One of the few agricultural areas of Puerto Rico is called Las Marias. The region is known for growing oranges for orange juice. I drove to Las Marias to meet with a small scale orange farmer.

[DRIVING SOUNDS]

Las Marias is way up in the mountains on the western half of the island. My drive is 13 miles but it took more than an hour on narrow, twisty, nausea-inducing mountain roads. My GPS signal failed and I got wildly lost. It’s difficult to get here on a good day. After the hurricane it was impossible. Las Marias was cut off from the rest of the island for 2 months and had to have supplies airlifted in by helicopter.

[CHICKEN SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Farmer Domingo Antonio Romano is 75 years old and has a small farm here with his wife, Nilsa. He walks past his chicken coop and stops in front of his only orange tree that survived the hurricane.

ROMANO: Only one, tenemos una sola.

BASCOMB: He used to have 20. Before the hurricane most of Domingo’s farm was made up of coffee, mango, and orange trees. The very crops most impacted by the storm.

ROMANO: (SPANISH) 90% of our farm was destroyed but it was really like 100% because with the hurricane no one could come here to harvest.

BASCOMB: Near the one surviving orange tree, amid debris of tree limbs and weeds, is a small patch of vining plants.

ROMANO: (SPANISH) This is a purple yam, they are very good.

BASCOMB: Root vegetables like yams were really the only food crops that didn’t get torn away by the 155 mile an hour winds of hurricane Maria. They were one of the only food crops the Romanos could still harvest and eat after the storm. But animals in the area were also struggling to find food. Wild pigs quickly discovered the purple yams and ate most of them.

ROMANO: (ENGLISH) Before Maria, we have many. But we have nothing.

BASCOMB: Domingo and his neighbors still had months to go before the roads would be cleared or the electricity restored. He says in that time they came to rely on each other for help.

ROMANO: (SPANISH) Before Maria, there was forest everywhere. And then, after Maria, the trees came down and we could see our neighbors and we got to know each other. After the hurricane, there was a lot of empathy between the people, and everybody helped each other. And the bees! We got to feed them. After the hurricane there were no flowers so we put out sugar water for them.

BASCOMB: His crops were destroyed and the roof torn off his house. They were without running water or electricity for months. Domingo says it would have been impossible for him to rebuild alone. But he’s not alone.

[CONSTRUCTION SOUNDS]

The Romano’s one remaining orange tree. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: 5 volunteers from a grassroots non-profit group called El Departamento de la Comida, the Food Department, are here to camp out on the farm for a week and do any work that needs to be done: clear land, plant crops, fix fences and repair the roof.

[CONSTRUCTION SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: The volunteer Food Department is organized into groups called brigades and are dispatched all over the island. As many as 20 people at a time descend on a farm for a week, bringing with them seeds, tools, building supplies, and the man power to get a farm back up and running. Edan Freytes is the leader of this brigade. He says they do this work because farmers are crucial for Puerto Rico going forward.

FREYTES: The farmer is the… the agriculture is like the espina.

BASCOMB: The backbone.

FREYTES: The backbone of the country. And it’s the most damaged sector. I think it’s the sector we need more to help, because it got the worse loss.

[COOKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Farmer Domingo’s wife, Nilsa, is in the kitchen cooking lunch for the volunteers… cassava root, sliced tomatoes, rice and beans. She lifts the top off a pot of soup she’s been working on since this morning.

N. ROMANO: (SPANISH) This has pork, bread fruit, green banana, onion, pepper, cilantro, and garlic.

BASCOMB: Nilsa says she’s happy to have the volunteers here. The work they are doing in a week would have taken her and her husband months. But beyond the physical help she is grateful for the emotional support and encouragement the volunteers bring.

N. DOMINGO: (SPANISH) It’s very emotional for me because I was very depressed. It was a very traumatic experience. For months we were without water, electricity and a roof. And we were alone. With this group here I’m just so grateful for the support. So grateful.

BASCOMB: The volunteer Food Department has set a goal to send brigades like this to 200 farms across Puerto Rico, large and small, organic and commercial. They simply want to support domestic agriculture in any form.

[MARKET SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Sonia Carlo from the Rincon Farmer’s market says she had similar support, not from an organized group but from friends, neighbors, and strangers volunteering their time to help her rebuild.

CARLO: What really got us through everything was the community. This, you know, we had a commitment to our community, especially in Rincon, people just said “what do you need, I’ll help you. What do you need, you need hands?” And we said “yeah, we need people.” “I’ll help you”. You know, and that gave us strength to keep growing and producing.

Volunteers with El Departamento de la Comida camp out in tents on a farm for up to a week to help farmers rebuild their farms. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: And Sonia says that outpouring of support has given her a new sense of purpose to keep on farming.

CARLO: Granted, you see me standing here, I'm working seven days a week. But I'm doing it with a smile on my face, because I know it's for good. You know, it's for the good of everything. And I know this is my journey in life and this is what we're going to be doing. No matter how many hurricanes come, we’ll still bounce back. Nothing is going to keep me out. Not even a category 5 hurricane.

Related links:

- El Departamento de la Comida

- El Fondo de Resiliencia

[MUSIC: Sierra Maestra on Sonando Ya, by Erden Hernandez, World Village Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – The personal story of living through Maria, and rebuilding for resilience. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana, helping boaters race clean, sail green, and protect the seas they love. More information at Sailors for the Sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Paco De Lucia, “Entre Dos Aguas (Instrumental)” on Vicky Cristina Barcelona, Universal Music Spain, S.L.]

“Pa’lante”: Puerto Rican Resilience After Maria

Gloria Vasquez points towards the broken and battered trees behind her house. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb. Some 3,000 people died on Puerto Rico as a result of Hurricane Maria. But most of those deaths were not from the wind and rain of the hurricane. It was the isolation that followed the storm that proved most deadly. The slow aid response after the hurricane left vulnerable people stranded for weeks and months. Many died from treatable infections, contaminated water, or electrocution from downed powerlines.

Nine months after Maria I found people that were looking to each other, not the government, to create more resilient communities and prepare for the next storm.

[DRIVING SOUNDS, GPS DIRECTIONS ‘IN HALF A MILE…’]

BASCOMB: To get to Humacao, Puerto Rico you can take highway 53, past McDonalds, grocery stores, and car dealerships. Except for the palm trees, it feels like you could be anywhere in the US. But turn up the narrow, twisty mountain road toward Humacao and it’s a different story. Electrical poles stick out of the ground at awkward angles. Electrical wires hang casually over the road, swaying in a light breeze.

NIEVES: There’s a lot of posts that look like they’re about to fall on people. Trees near highways that look like they are about to fall on cars. And that actually happened.

BASCOMB: Christine Nieves is director of Proyecto Apoyo Mutuo, the Mutual Aid Project, based in a community center at the very top of the mountain in Humacao. Christine says downed power lines and unstable trees are now common here.

Christine Nieves is director of Proyecto Apoyo Mutuo, the Mutual Aid Project, founded after Hurricane Maria to help her community recover from the storm. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

NIEVES: There was a tragedy not too long ago of a young man dying from having a tree collapse on top of him. So you’re still seeing that.

BASCOMB: Christine is petit with wavy black hair and a bright smile. She wears a flowy pink top and long earrings. She left Puerto Rico to go to college at Penn State and then got her master’s degree at Oxford in England. She came back to Puerto Rico 6 months before Maria hit the island and settled here in Humacao, where the hurricane actually made landfall.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Christine leads the way across a large parking lot to the edge of the mountain and points to a wide green valley below us.

NIEVES: So this is where the eye of the hurricane entered.

BASCOMB: Through this valley?

NIEVES: Yes. It actually made landfall first in this community and all of these mountains.

BASCOMB: Just to describe this area where we are. So right there is the ocean, so that’s obviously where the hurricane came in and just traveled up this little valley in between us here, between the mountain that we’re standing on and that mountain over there and hit these homes right in front of us.

Hurricane Maria travelled up this wide green valley to the interior of Puerto Rico. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

NIEVES: Mmhm, absolutely.

BASCOMB: Were you here during the hurricane?

NIEVES: I was, yeah. My house is actually not too far from here.

BASCOMB: So what did it feel like?

NIEVES: It was chaotic. We prepared so well because we had basically a two-week heads-up. We were prepared from Irma already. We had storm shutters were up. We got water you know, a few days before the hurricane and we filled our cistern. But the actual hurricane, because we were so close we started feeling it on the 19th. One in the morning, we wake up - we start feeling, and hearing, the sounds, and it’s just loud and you can barely hear each other. And that’s when we started noticing that the water was coming in, through all the windows.

These homes in Humacao were some of the very first in Puerto Rico to feel the impacts of the Hurricane. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Into your house?

NIEVES: Yeah, through all the windows. Through the storm shutters, it didn’t matter. It was just coming through. And at first we were actually trying to figure out if we could dry the water and like address that. And then we also started noticing, we have all of our doors, our glass sliding doors, and we noticed that the glass was bending inward, so to try to keep it from being pushed into the house, we took all of our furniture and backed it up from the door to the wall, like in a chain. It was like, the table, and the chair, and the bookshelf - and everything supported each other all the way to the nearest column.

But that didn’t help. And it was around 4 in the morning that the skylights exploded in, and then the window exploded in as well. So there was glass flying. So at that point we actually got into the safest spot, which was a bathroom under the staircase that had no… other than the door, there was no way of getting in or out. We got in -- dog, cat, three adults, in this tiny bathroom, and just waited. And then we started seeing the water coming in from under the door. It’s just like coming in, and coming in, and we’re just like, what do we do? So we just put everything we had and basically everything that got wet we had to toss away.

And it was just, the hurricane came in. So… it was not just water, it was leaves. And then the painting from inside the walls was stripped… scraped off from the pressure. It was like a pressure washer had come into the house and just scraped… not only outside, but inside.

BASCOMB: The paint came right off your walls?

NIEVES: Mm hm.

BASCOMB: That sounds really scary.

NIEVES: Oh yeah. I mean, it was… Luis is a musician, so he was playing - my partner - he was playing the guitar. His cousin is also, you know, his entire family plays some sort of instrument, so he was playing the drums, or the percussion. So we were dealing with it by singing. And we spent the entire hurricane like that. And then once we actually got into the bathroom there was not a lot of space, so we kind of took a nap, sometime in the middle of the night, because you’re so exhausted, and there’s nothing you can do, you know, everything’s getting destroyed. And when we came out at 7 in the morning, we noticed that the, our 2,000 gallon cistern - something had come off, so the entire cistern was getting, was emptying out. And that was just at the moment when the wind was changing directions. So we never felt the calm of the storm, we were kind of… it was basically the wall of the eye, we never got the actual eye.

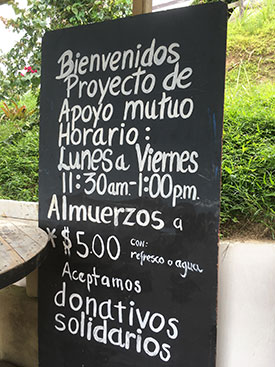

A sign advertises that the Mutual Aid Project accepts $5 “solidarity donations” for lunch Monday through Friday. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

So this was like, that wall of the eye just passed right through us. And we got, because of our altitude, we also got the strongest winds, and some of the storm shutters were actually pulled off from the wall. It was like, it was something so massive that you can’t quite understand it and comprehend it, when you see that something that’s designed to withstand storms didn’t, that’s when you realize, ok, we’re dealing with something that’s beyond the scales that we’re used to.

BASCOMB: So this forest right in front of us, I mean, you can see that it used to be a forest, and it still is to some degree, but there are no leaves really on the side of the trees and all of the tops are cut off at the same length, at the same height.

NIEVES: Mm hm, mhm. Yeah, so, all of these trees that you see here, they were massive. You couldn’t see beyond them. It was so thick, you couldn’t see the houses even. It looks much better eight months later, because nature is so wonderful and it can bounce back so much faster than human beings can in many ways. But that was actually one of the first things I noticed, that even before FEMA had arrived to Mariana, we were seeing the trees bouncing back. So the trees were faster in their response, than FEMA even.

BASCOMB: Yeah, it looks like just a big chainsaw went through and just cut the tops off everything and stripped the sides off the trees.

NIEVES: Yeah. It was like a bomb exploded. And it was also… if you had come here the days after, it looked just like sticks, like matchsticks, just like sticking up, everything looked grey, and it was actually one of the hardest things, because people who live here, obviously, love nature, and it’s one of the reasons why I moved back, and it was very hard to see the amount of destruction.

BASCOMB: When you came out here the day or two after the hurricane and you looked out here, how did it make you feel to see it look so different, to see the trees just denuded?

NIEVES: Well, when we walked out of the bathroom and went to one of the windows in the house, we were on the bottom part of the house… oh my god, I - Luis, actually, my partner, he started crying, because those were the trees that he grew up with. And it was just a complete feeling of… it was like all the movies that you’ve seen of Armageddon, of destruction, of the end of days, it was like - this is done. And the fact that the communication collapsed meant that also we couldn’t hear the government, but we couldn’t hear each other. All we had was the people next to us.

Eight months after the storm Puerto Ricans were still being injured and killed by falling trees and electrical poles. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: In my two and a half weeks reporting in Puerto Rico I heard this same sentiment over and over again. Communities were isolated, FEMA and the government were slow to respond, so people turned to their neighbors for help. In many cases the dense forest before the hurricane had blocked their view of each other. People might not know there was a house across the street or down the way a bit, but after Maria turned the lush forest into matchsticks, neighbors could see each other for the first time and came to rely on one another for help.

NIEVES: The people in this area that are starting to understand that the government is not going to respond and save them, it’s actually going to be their neighbors -- having, you know, the machetes ready. Knowing how to disinfect a wound. That’s one of the things that they saw the most, was wounds that could have been disinfected ended up in amputations. So they had to cut so many feet off because people were in flip-flops in standing water that had infections and they just couldn’t, they didn’t have something like iodine or something that could be easily over-the-counter, anyone can have, disinfecting the wound at the right time. So, it’s that kind of education and preparedness and it’s also community organizing, to prepare for the next hurricane.

BASCOMB: Most of the residents of Humacao are older, retirees who live alone and have been without electricity since the hurricane. Christine takes me to meet one of them.

NIEVES: So, let’s go find Gloria.

BASCOMB: So, I’ll just follow you guys in my car.

NIEVES: Yeah.

[CAR SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: I follow Christine down the mountain to meet Gloria Vasquez at her house a few miles away. A downed electrical wire grazes the top of a car parked in front of her house. She’s standing on her porch watering a potted pepper plant.

Gloria Vasquez standing in her living room. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Buenas!

VASQUEZ: Hello, buenas!

BASCOMB: Como estás?

VASQUEZ: Bien, bien. Gloria.

BASCOMB: Ah, Gloria, mucho gusto. Bobby.

VASQUEZ: Entónces… (In English) Let me show her something I am planting.

BASCOMB: Of course.

BASCOMB: Gloria is 70 years old. She wears an oversized red t-shirt and her hair slicked back in a small ponytail. Her house sits on the side of the mountain overlooking the valley. She can see clear to the ocean some 40 miles away. Before the hurricane Gloria says she could only see the dense forest in her yard and an avocado tree taller than her house.

VASQUEZ: The tree, it was so big, tall. It feel me very, very bad. And I cry like crazy. Because I don’t think that Puerto Rico is going to be like that, you know.

BASCOMB: You didn’t think it could look like that.

VASQUEZ: No, no, no. No, I don’t think it’s going to be like that. And still I hurt. I feel, you know, about what happened to Puerto Rico.

BASCOMB: Gloria has accepted her lost trees and the broken landscape, but she’s still struggling to deal with the day to day life, living alone without electricity.

VASQUEZ: It’s hard. Sometime I sit there and I cry because the light, I need the light, you know? I don’t have no fridge, to cool my stuff, because I got diabetes and I need to put my insulin in the fridge.

BASCOMB: So what do you do?

VASQUEZ: What I do? Sometime I take it the lady in my neighborhood, Sandra, and then Sandra let me, give me a key to put them inside the refrigerator. She got a generator.

BASCOMB: So what do you do, how do you manage it at nighttime?

Each week a group of volunteers gathers to cook for the community. Feeding their neighbors is a type of therapy. The ladies get out of their lonely dark homes for the day and connect with friends. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

VASQUEZ: By 6:30 it’s starting getting darker, so I lock the gate and I lock the door and I stay inside the house, ‘cause you don’t know, you know. There’s a lot of thief here.

BASCOMB: A lot of theft.

VASQUEZ: Yeah. They ask me, oh are you there by yourself? - no, I’m not by myself. I got a husband. My husband is the police and he is working.

BASCOMB: Gloria lived most of her life in the Bronx. She moved there as a teenager with her family and worked for 50 years, mostly as a hair dresser. She saved her money all those years to retire in her native Puerto Rico where she bought this 3 bedroom cement house.

VASQUEZ: You want to come inside the house?

BASCOMB: Yeah.

VASQUEZ: This is the living room over here. This is my dining room, and the kitchen. You see, it’s dark. Let me get the flashlight.

BASCOMB: Gloria shows me around her dark house. She pauses at a crèche and a statue of the Virgin Mary given to her by her mother.

VASQUEZ: She gave me this one and this one here. They always here with me. Those are the ones that take care of me.

BASCOMB: She points out framed pictures of her grandchildren and her three sons.

VASQUEZ: That’s my baby boy here, when he graduate.

BASCOMB: How old is he now?

VASQUEZ: He’s going to be 40. And that’s me when I graduate from beauty school. Midway Beauty School in New York.

BASCOMB: In her tidy kitchen, Gloria has a few vegetables on the counter, a gas stove, a refrigerator empty but for a bottle of maple syrup, and a small red cooler on the floor where she keeps perishables like milk.

VASQUEZ: But I don’t buy no meat, because meat is getting worse quick.

BASCOMB: It goes bad quickly.

VASQUEZ: Yeah.

BASCOMB: What do you eat then?

VASQUEZ: If I want to eat something, I go into the store right there, I buy whatever I want to eat, and then I bring it. Today I’m gonna eat verdura.

BASCOMB: Vegetables.

VASQUEZ: Yeah. This is my dinner for today.

BASCOMB: Eggplant and plantain.

VASQUEZ: Eggplant, banana, and potato. That’s my dinner and my lunch, is going to be today. And this, hamonia.

BASCOMB: That’s like spam.

Maria cooks up chunks of pork for lunch at the community center in Humacao. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

VASQUEZ: Yeah, spam. And then I cook it and eat half, and I leave the other half for later. That’s the life here. Hard, hard. But what I gonna do?

BASCOMB: That’s the life for most of the residents in Humacao. The majority of people here are elderly, living alone, and without power. That isolation can be depressing and deadly. But since Maria hit, locals are looking to each other for solace and sustenance.

[DRIVING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: The next day I drove the twisty road back to the mountaintop community center in Humacao. Half a dozen older women have gathered today to cook for their neighbors, as they do each week, Monday through Friday.

There’s a sign out front that indicates when they’ll be cooking and says ‘aceptamos donativos solidarios’ – ‘we accept solidarity donations’. For five dollars anyone can buy a homemade lunch of rice, beans, and meat. Maybe some fruit if one of the ladies has extra papaya or pineapple coming up at home. Today a woman, ironically named Maria, is cooking up chunks of pork.

[SIZZLING SOUNDS]

MARIA: I like to make the meat soft and nice and tender. Would you like a bite?

BASCOMB: It’s very good.

MARIA: It is, it is. Rice and beans… oh gosh we’re eating good here.

BASCOMB: Maria says coming here to feed the community is a type of therapy for her. She gets out of her lonely dark house for the day and cooks with her friends. They chat about family and argue like sisters. Life feels normal again.

This theme of working together and resilience is everywhere in post-Maria Puerto Rico.

Lunch is served! For $5, anyone can buy a lunch of rice, beans, and meat. Beyond food, community members can connect with one another and feel less alone. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

About 9 months after the storm a local musician named Hurray for the Riff Raff produced a song in part about recovery on the island. The music video shows scenes of a hurricane-ravaged community, and tells the story of a young family trying to work through it.

[MUSIC: Hurray For The Riff Raff, “Pa'lante” on The Navigator]

SINGER: From El Barrio to Arecibo,

Pa’lante…

From Marble Hill to the ghost of Emmett Till,

Pa’lante…

BASCOMB: Pa’lante is truncated from the Spanish phrase para adelante, which literally means move forward, but Humacao community organizer Christine Nieves says it means much more than that now.

NIEVES: So, ‘pa’lante’ means we’re going to keep moving forward, we’re going to keep rising, and we’re going to keep fighting. And I think it also means, for me it’s about connecting with the root. We’ll look back at this moment in history and I think it’ll have a huge fork in the road in what it does to the Puerto Rican psyche. The conclusion at the end of this disaster that we’re still living in is that it’s us, we were the ones that could respond. We were the ones that had to and that were capable of saving lives, and it was community members that were capable of doing it. So, pa’lante. We keep building, we keep building.

[MUSIC: Hurray For The Riff Raff, “Pa'lante” on The Navigator]

BASCOMB: If there’s any silver lining to the devastation that Maria brought here it might be this: a renewed sense of community, Puerto Rican pride, and resiliency that people hope will keep them moving forward to rebuild and meet the next challenge together.

[MUSIC: Hurray For The Riff Raff, “Pa'lante” on The Navigator]

Related links:

- Proyecto Apoyo Mutuo

- Hurray for the Riff Raff

BASCOMB: Coming up – Puerto Rico’s coral reefs took a beating from Hurricane Maria.

LOREANO: The first time we went to there after Maria, the reef was like destroyed, like we see big coral colonies upside down and a lot of dead coral.

BASCOMB: But there’s still hope for their recovery. Keep listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Gipsy Kings, “Valse gitante” on Rare & Unplugged, Newsound 2000]

Volunteers Test Drinking Water in Puerto Rico

In 2017 Hurricane Maria knocked out so many trees and powerlines so that roads were blocked and supplies had to be air lifted into remote communities like this one near Utuado, Puerto Rico. (Photo: Coast Guard News, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb. When Hurricane Maria made landfall, it knocked down trees and power lines, leaving roads impassable and communities isolated for weeks and months. Even towns in popular tourist areas found themselves cut off from the outside world and struggling to meet their most basic needs. Safe drinking water became one of the most immediate and pressing issues across the island, and also an important teachable moment.

[MARKET SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Rincón sits on the west coast of Puerto Rico. It’s a mecca for surfers and beachgoing tourists. The town has a quaint square with gourmet coffee shops and a lovely farmer’s market.

[MARKET SOUNDS]

CARLO: Cómo estás? Wow…

BASCOMB: Sonia Carlo has a farm stand at the market where she sells some salad greens, kale, and pineapple. She was on the farm with her husband and 3 children when Hurricane Maria struck. She says one of the biggest challenges was just providing the essentials for her children during and after the storm.

CARLO: And you know, they were just so scared that they weren’t going to be able to drink water. You know, it's hard to tell a three year old “don’t drink all the water, we're going to run out” or “don't eat too much food”. Yeah…

BASCOMB: But when their bottled water ran out, she found an alternative the kids liked even better.

CARLO: I had no choice but to give them soda. So they're -- you know, they're innocent, they said, “We like the hurricane! Mommy’s giving me soda and sweets!” Because, you know we had no choice, it was between letting them go thirsty or giving them, you know, soda -- which, they had never tried soda before. So…

BASCOMB: Eventually the soda also ran out, and Rincón didn’t get reliable drinking water for several months. In that time the incidence of water borne disease increased greatly. There was a sharp rise in gastrointestinal issues, scabies, and leptospirosis, a bacterial infection caused by fresh water contaminated with rat urine.

TOMAR: It really put into focus this water quality issue.

BASCOMB: Steve Tomar is originally from Florida but he’s been living in Rincón for more than 40 years. He’s tall and lanky with long brown hair and a gray beard. He says getting drinking water was a problem for everyone after the hurricane.

Steve Tomar stands in front of Rincón’s only source of drinking water after Hurricane Maria. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

TOMAR: There is no water authority water, and the stores are closed because they don’t have generators. Or if they do have generators they sold out of water days ago. And you knew that it was going to be like that for months. So, you immediately had to resort to whatever your closest source of natural, what we call informal, sources of water were… springs, wells or streams.

BASCOMB: So, you come down here, you dip your cup in the stream and hope for the best.

TOMAR: Yeah, that was literally, for the vast majority of the island, that was it. Just hope for the best.

BASCOMB: And that presented a whole host of other problems. No one had any idea if water from those streams and springs was safe or not. But that was a problem Steve could work on. He’s vice chairman of the Rincón chapter of the Surfrider Foundation and director of the Blue Water Task Force, which tests ocean water quality near the beaches.

TOMAR: So, immediately after the storm people were going hey, can you do something about checking the wells and springs and stuff? And we said, well, we’re not set up for it but yeah, yeah we can do this. Within 3 weeks we could get up and running after the hurricane, as opposed to the government agencies – it was like 3 months at the earliest before they started responding.

BASCOMB: The only tests they had on hand were for enterococcus, a hardy bacteria that can survive in a marine environment, so that’s what they began testing for. After they were able to get the right supplies, they began testing the water for other, more likely, contaminants, including bacteria from fecal matter.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: I met Steve at a park near a small stream. Little bubbles from an underground spring pop up every few seconds.

TOMAR:This literally after the hurricane was where everybody that lived in downtown Rincón had to come for their water. This was the only source they had.

BASCOMB: So, Steve and his team began their testing here and quickly branched out to include much of the surrounding area. They gave an expedited training course to Boy Scout groups and anyone interested in learning how to do water quality testing. Within a few months they tested most of the informal water sources within a 6 hour radius. After 6 hours, a sample can no longer be accurately tested.

Today, Steve is testing this stream again. He repeats sampling every few weeks to monitor the bacteria count to be prepared for the next hurricane. He takes out a sterile 100 milliliter collection bag.

TOMAR: We very carefully remove the perforated top. And you do not throw your plastic into the environment. No, we have that problem already.

BASCOMB: He holds the bag by a yellow handle and dips it into the stream. Then he takes the sample to a bench under a shady tree.

Supplies for initial water testing at the spring. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

TOMAR: Here we are with our temporary lab set up at the site.

BASCOMB: He tests for ph, temperature, nitrates, chlorine and sediments, and writes down the results on a data sheet.

[WRITING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Then he’ll take the sample back to his lab in the Surfrider office and test for the things that can really make people sick, including coliform, enterococcus bacteria, and E. coli. This particular stream has levels of enterococcus at twice the federal standard, enough to close a beach if this were a marine sample. But after the hurricane it was drinking water, so Steve’s team put up signs to notify people.

TOMAR: We had color-coded green, yellow and red signs. Boil for a minute, boil for 5 minutes, and boil for 20 minutes -- and quite frankly I wouldn’t be drinking it in the first place because if you’re finding that much bacteria you’re probably also going to have a lot of other, a whole suite of other problems that you wouldn’t want to use for potable water.

BASCOMB: Steve says in the past, they were reluctant to take on testing drinking water.

TOMAR: Because of course you’re stepping on all sorts of toes with various government agencies and the public health services, and blah blah blah…. After the hurricane that became a moot issue. And it was just like of course you do it, because this is the community. These are your people so whatever you can do to keep them healthy and informed, you do it.

BASCOMB: Surfrider’s Blue Water Task Force to test ocean water quality is the largest citizen science program in Puerto Rico. And Steve says it was relatively easy to transition the skills volunteers developed for testing ocean water into testing drinking water. But he sees value beyond just water safety.

TOMAR: In a lot of ways I think the major benefit of these community-based science programs is developing skill sets in the community. An educated populace is of course a populace that’s better able to take care of their own resources.

BASCOMB: Thay-Ling Perez is an intern with Surfrider and local to the area. She says that if there’s any silver lining here it’s the sense of community that came out of working together to get through the hurricane.

PEREZ: You also saw a lot of togetherness and community. People got to know their neighbors, which was a big deal here because a lot of people didn’t know their neighbors, they lived isolated in their world. So it’s still something beautiful that came out of it but it was also from a lot of pain.

BASCOMB: As climate change continues to warm the oceans and create optimal hurricane conditions, big devastating storms like Maria are likely to become more common in the future. Puerto Ricans have painfully learned that the government was not able to quickly respond after a hurricane, so they’re looking to each other instead. And across the island, Puerto Ricans are learning the skills they’ll need to ride out the storm together.

BASCOMB: Since this story originally aired, studies have found elevated levels of nitrates in Puerto Rico’s waterways, likely a result of decomposed leaves and branches from the damaged forests. Nitrates serve as a fertilizer which can lead to algae blooms and fish die offs.

Related link:

Rincón, Puerto Rico chapter of the Surfrider Foundation

[MUSIC: Sierra Maestra, La vida sin ti, on Sonando Ya, by Rafael Fernandez, World Village Records]

Repairing Puerto Rico’s Corals

Grupo Vidas workers have used zip ties to reattach hundreds of coral fragments to the reef near Vega Baja. (Photo: Ricardo Loreano)

BASCOMB: In the tropics, coral reefs are a first line of defense against devastating storms like Hurricane Maria. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA, estimates that roughly 10 percent of corals in Puerto Rico were damaged in the storm. Chunks of coral were broken off by rough seas and ocean swells. But I discovered there’s still hope for thousands of battered bits of coral lying around the sea floor.

[WAVE SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: I’m standing on a tall dune near Vega Baja on Puerto Rico’s north coast. The ocean stretches out in shades of dark blue, turquoise, and pale aquamarine.

But interspersed among the usual colors of a tropical ocean are patches of brownish orange – elkhorn coral. Salvador Loreano is a worker with the environmental NGO Grupo V.I.D.A.S. Their main task is coral restoration.

S. LOREANO: Our goal right now is to plant coral fragments here because you know that Maria, Hurricane Maria, came here and devastated the island. This caused great damage to the coral reef because the first time we went to there after Maria, the reef was like destroyed, like we’d see big coral colonies upside down and a lot of dead coral.

The Grupo Vidas crew taking a break from their coral restoration work. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: As long as they remain submerged under water, these coral, which are colonies of tiny invertebrate animals, have a 20 percent chance of survival. But that increases to more than 90 percent if they are attached to a larger structure, not getting banged around by the surf or smothered with sand.

If a piece of coral is at least 2 inches long and 80 percent healthy, it can actually be reattached to an existing reef. Salvador points towards the water…

S. LOREANO: Over there is my sister and that’s one of my friends that work here. They’re preparing to enter to the Arrecife El Eco.

BASCOMB: Can we go see what they’re doing?

S. LOREANO: Yes.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Mariola Loreano is standing on the shore in about a foot of water.

S. LOREANO: Mariola!

Ernesto Vélez Gandía stands on the beach getting ready to reattach bits of coral broken off the reef by Hurricane Maria. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: She’s wearing a rash guard to protect from the hot tropical sun.

A mask is perched on her forehead, a snorkel dangling off it. She’s holding a white milk crate with all the tools the crew will need for their morning’s work.

M. LOREANO: Yeah, basically what we have in there is a sledge hammer; a slate where we write our tallies, basically, which is all of the fragments that we’ve successfully planted; a bag for any trash that we find inside the ocean; a buoy so it floats.

BASCOMB: So, should I put on my fins then and we head in?

S. LOREANO: if you’re using flippers, I recommend that you either walk sideways or back because, you know, if you use flippers walking front, it’s going to be rather difficult.

BASCOMB: I’m going to fall on my face.

S. LOREANO: Most… mostly. [LAUGHS] I can help you enter the reef, because, well, it’s all rocky, but there are a lot of sea urchins there.

BASCOMB: Oh, so it’s spiny.

S. LOREANO: Yeah, but it’s not that big of a deal because they’re really deep inside the crevices so they won’t sting you.

BASCOMB: So, is there any other advice I need before we go in?

S. LOREANO: One thing you got to be careful of, it’s not that big of an issue, but scorpion fish have also appeared here. You know how they camouflage very well?

BASCOMB: I don’t actually.

The beach near Vega Baja, Puerto Rico. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

S. LOREANO: They rely on their camouflage. And sometimes their camouflage is really good. [LAUGHS] So it’s best to keep an eye out where you put your hand and everything.

BASCOMB: I’m not going to touch anything.

S. LOREANO: I know, I know! – just in case.

[SOUNDS OF WATER SPLASHING]

BASCOMB: We put on our mask, snorkel, and fins and walk backwards into the bath-warm water, stepping over the sharp black sea urchins.

[SPLASHING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Once the water is knee-deep, we splash in and swim about 500 feet to the reef.

[UNDERWATER BREATHING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: A rainbow of fish greets us – green fish with florescent blue heads, black fish with yellow stripes, green fish with pink stripes. They’re all juvenile fish, and the reef is a critical habitat for them. Bulbous brain coral dot the sea floor, and orange elkhorn coral stick out at awkward angles, much like its namesake.

[SCRAPING SOUND]

BASCOMB: A worker named Ernesto is already hard at work.

He uses a wire brush to scrape algae off a piece of coral the size of a ping pong paddle and does the same to a suitable spot on the reef. Just like gluing two objects together, you need to start with a clean surface on both sides. Then he pulls a plastic zip tie out of his sleeve and uses it to attach the coral in place.

A piece of dead brain coral washed up on the beach. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

He uses pliers with a florescent pink handle to pull the zip tie tight and cut off the excess plastic, which he sticks into his other sleeve. This piece of coral is now one of hundreds just like it pinned to the reef with zip ties. And in two to three weeks, it will grow onto the reef enough to stay put on its own.

[WAVE SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Roughly 15 percent of the coral here at Vega Baja was broken off by hurricane Maria. But these corals evolved with hurricanes. If hurricane damage was the only issue, this work wouldn’t be necessary. But much like the world’s coral reefs in general, this reef has a lot of challenges.

Grupo V.I.D.A.S. worker Ernesto says one of the biggest problems is algae blooms from sewage runoff. In many places the coral is essentially smothered, leaving it a ghostly gray color.

VÉLEZ GANDÍA: Yeah, those… they look like zombies, right there.

BASCOMB: They look like zombies, like Day of the Dead.

VÉLEZ GANDÍA: Yeahh, it’s like Day of the Dead but under the water.

BASCOMB: There is a very large dead coral at the entrance to the reef in the shallowest, warmest water. Ernesto believes that one died not from algae blooms but from stress of a warming ocean.

VÉLEZ GANDÍA: The water is getting warmer. Every year it’s getting warmer.

BASCOMB: Standing on the dune in a light blue rash guard and smoking a cigarette, Ernesto talks about the death of that coral as one might talk about a member of the family passing away.

VÉLEZ GANDÍA: And we got a lot of love for him. We saw him alive, very alive. He is one of the oldest in our reef. But he start dying, we saw the process of his death. So, we just admire him and remember him. It’s very sentimental, I don’t know, but it’s deep in the heart.

BASCOMB: Adding to the warming water and algae blooms, ship groundings break off large chunks of coral each year; collectors intentionally break it off to sell for home aquariums; and spear fishermen damage it with their equipment.

Elk horn coral are part of a vital reef ecosystem that provide habitat for fish. (Photo: Sean Nash)

Ocean acidification and coral bleaching are also huge problems for the world’s corals, and Puerto Rico is no exception. The team admits it’s an uphill battle to save this reef, but Salvador says they’re already seeing results.

S. LOREANO: Our work has given us results like species that we thought we’d never see again started to return, like moray eels, scorpion fish, sea cucumbers, puffer fish, sand dollars, which are a species of flat sea urchin, and also there’s like a spotted eagle ray hanging around over there.

BASCOMB: Projects like this have actually been going on for nearly 20 years on a small scale. But one million dollars of post-Maria funding allowed scientists from NOAA, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, and independent NGOs to speed up their efforts. Workers have been able reattach roughly 15,000 pieces of coral to the reefs surrounding Puerto Rico.

Related links:

- Índice | Lifeguards of Our Reefs

- Grupo V.I.D.A.S.

- NOAA page on Corals

[MUSIC: Gipsy Kings, “Valse gitante” on Rare and Unplugged, Newsound 2000]

BASCOMB: There’s one more story from Puerto Rico that we couldn’t fit into this week’s broadcast. It’s about how Puerto Rico’s forests were affected by the hurricane.

It’s on our website, LOE dot org.

[MUSIC: Gipsy Kings, “Obsesion De Amor” on Compas, by T. Baliardo, Nonesuch Records]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. See us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Steve Curwood will be back next week. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth