May 31, 2002

Air Date: May 31, 2002

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Powder River Gas Drilling

/ Eric WhitneyView the page for this story

The Bush administration is poised to drill tens of thousands of coalbed methane wells in the Powder River basin area of Montana and Wyoming, but critics, including the EPA, are charging that the federal environmental impact studies for the proposed gas drilling are inadequate. (06:15)

9/11 Contrails

View the page for this story

When the FAA shut down commercial air traffic for three days last September, researchers were able to test their theories about how jet contrails can influence weather. Host Steve Curwood talks with atmospheric scientist David Travis about his study. (05:00)

Health Note: Brains on Estrogen

/ Jessica PenneyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Jessica Penney reports on research that suggests estrogen may play a role in problem-solving abilities. (01:15)

Almanac: Yard Sales

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about yard sales. The world’s longest yard sale stretches 450 miles across three states, and is guaranteed to have something for everyone. (01:30)

Southwest Drought

/ Ken ShulmanView the page for this story

New Mexico, like most of the southwest, is suffering its third year of drought. And people are fighting over who owns the rights to the water. But as Ken Shulman reports, the thirst for water is nothing new in this arid state. (07:40)

Picky Pig

/ Sy MontgomeryView the page for this story

Commentator Sy Montgomery laments the good old days when her 750-pound pig Christopher Hogwood used to eat regular old slops. Ever since a big storm knocked out electric power and neighbors brought over all their melting ice cream the pig has been spoiled rotten. (04:30)

Traditional Medicines

View the page for this story

The World Health Organization has released the first global strategy to document and protect traditional and alternative medicines. Host Steve Curwood spoke to the W.H.O.’s Jonathon Quick about the project. (03:00)

Tech Note: Virtual Help for Parkinson’s

/ Cynthia GraberView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Cynthia Graber reports on a new virtual reality device to help Parkinson’s patients walk more easily. (01:20)

Listener Letters

View the page for this story

This week we dip into the Living on Earth mailbag to hear what listeners have to say. (02:00)

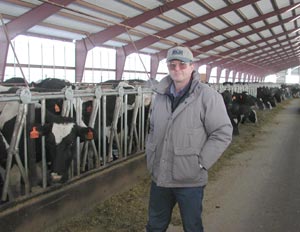

New Dairies

/ Guy HandView the page for this story

Producer Guy Hand reports on the migration of dairies from California. Dairy farmers are looking to escape urban sprawl and strict environmental regulations and many have re-settled in Idaho’s Magic Valley. Dairy farmers and long-time state residents say the explosion has been a mixed blessing. (14:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

REPORTERS: Eric Whitney, Ken Shulman, Sy Montgomery, Guy Hand

GUESTS: David Travis, Jonathan Quick

UPDATES: Jessica Penney, Cynthia Graber

[INTRO THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From National Public Radio, it’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. It used to be the potato was the agricultural symbol of Idaho. No more. Milk is now the state’s number one farm product. And it’s given local economies a much-needed shot in the arm.

LEDBETTER: It’s just incredible. As you start adding up the businesses in this little town that are there because the dairies are here, it’s a huge economic impact.

CURWOOD: But for some, prosperity has come with a price.

MIDKIFF: The problem here is you’ve got just too many cows in one place.

CURWOOD: Factory farm dairy herds are coming in from heavily regulated states like California. And some folks don’t like it.

MIDKIFF: They’re pollution shopping. They’re looking for places where they can get away with contaminating the air and water, fouling the land and running family farmers out of business. I mean, that’s really what this is all about.

CURWOOD: The dairy dilemma in Idaho, this week, on Living on Earth coming up right after this.

[THEME MUSIC]

Powder River Gas Drilling

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The Powder River flows north from Wyoming into the Yellowstone in Montana. The region is popular with tourists who come to take in the breathtaking views of the Bighorn Mountains. But these days, the Powder River Basin also attracts drillers who want to tap one of the nation’s largest natural gas reservoirs.

The federal Bureau of Land Management holds the rights to these deposits and is set to let industry begin drilling tens of thousands of methane wells there. But critics, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, say the BLM is ignoring the project’s long-term consequences. Eric Whitney of High Plains News reports.

[SOUND OF DRILLING MACHINERY]

WHITNEY: Another natural gas well is being drilled into the scrubby tan soil of the Powder River Basin in Wyoming. These drillers are using a relatively new technique to harvest gas. It’s been known for decades that the massive, shallow coal deposits here contain a lot of methane, a form of natural gas. That gas is trapped in the coal beds by groundwater.

In the late 1980s, drillers discovered that pumping the water out freed the gas, which they could then collect and sell to an energy hungry public.

[SOUND OF WATER TRICKLING]

WHITNEY: The Bureau of Land Management is endorsing a plan for 80,000 wells in the Basin that would, over the next two decades, pump up close to three trillion gallons of groundwater. That’s enough water to cover Connecticut and Rhode Island a foot deep.

[SOUND OF IRRIGATION SYSTEM]

WHITNEY: Roger Mugli is a farmer and feed processor near Mile City, Montana. He also runs this local irrigation system.

MUGLI: So when you open those head gates, the water comes over the top of that, and passed in there. Well, right ahead of that wall is an outlet that takes the sand and dumps it into the river.

WHITNEY: Irrigators, like Mugli and environmentalists, say the BLM doesn’t know the long-term consequences of coalbed methane wells bringing so much water to the surface. And, ironically, even in the middle of the worst drought in decades, farmers think disposing the excess water in local rivers and streams is dangerous.

MUGLI: It’s so laden with salts, sodium bicarbonate mainly, and that just does not work to irrigate crops. And pretty quick, the soil will start to collapse and then you don’t grow anything. No water will get into it, and no air and, therefore, no plant growth whatsoever.

WHITNEY: At this point, just over 200 coalbed methane wells are discharging wastewater into one Montana river. If government plans for development go through, more than 18,000 wells would discharge into three more. Mugli thinks that would be the end of irrigated agriculture in this part of the state. He’s already seen changes in the soil he tills.

MUGLI: You see the cracking? As it dries out, the moisture evaporates, and the salt isn’t going to evaporate. So there you have it. It turns that white.

[SOUND OF BIRDS SINGING]

WHITNEY: A couple of hundred miles south, in Wyoming, the water is less salty. But ranchers here are already seeing prime grazing land flooded. Looking for help, farmers and ranchers took the unusual step of joining with environmental groups to ask the BLM to slow the pace of drilling until the environmental effects could be better addressed.

Tom Darin is the staff attorney for the Wyoming Outdoor Council. He says it’s not just water quality that will be affected.

DARIN: The wells in the Powder River Basin are going to require, in this eight million acre area, 17,000 miles of new roads, 20,000 miles of pipelines, 5,300 miles of overhead power lines.

WHITNEY: The coalition told the BLM it wants water treatment made mandatory in sensitive watersheds. It’s also calling for drilling techniques that would minimize impacts to the environment, ones endorsed by President Bush’s own energy plan. But Darin says his group’s input was ignored when the BLM released two environmental impact statements a couple of months ago.

DARIN: BLM can study this if it wants. But, if it does a poor study, then it really hasn’t done its job.

WHITNEY: The Environmental Protection Agency agreed. The Agency told the BLM that its environmental analyses of drilling projects, on both the Montana and Wyoming sides of the basin, are insufficient and make unsupportable conclusions. The EPA urges BLM to do significantly more study, and to rewrite its analyses.

Gary Davis is the President of a local coalbed methane company. He says industry can be trusted to develop responsibly and feels that drillers are being held to an impossible standard.

DAVIS: We can’t have the kind of development, the engine for our economy, the ability for people to build large new houses, and heat and light them, and drive vehicles, and have no impact at all. As long as we’re dependent on the fossil fuels for those things, there will be a price that we have to pay.

WHITNEY: But Wyoming Outdoor Council’s Tom Darin says that unless BLM rewrites its environmental studies to be more realistic about development’s price, it’s leaving itself open to legal challenges. That’s already happened. In April, a federal appeals board revoked three drilling leases issued by the BLM, saying the agency had failed to adequately study their impacts.

DARIN: They’re sitting on a time bomb of when and at what point will someone come into federal court to try to invalidate their leases.

WHITNEY: The BLM says it’s working with the EPA to address that agency’s criticisms. But, the BLM is under pressure to open new methane gas production here this fall. Industry is already complaining of delays. So a major rewrite of the environmental impact statements appears unlikely.

[SOUND OF MACHINERY]

WHITNEY: Whether or not drilling in the Powder River Basin turns into a federal legal battle, what happens here will reverberate up and down the Rocky Mountains. Proposals to drill tens of thousands more similar wells are pending in New Mexico, Colorado and Utah as well. For Living on Earth, I’m Eric Whitney in Gillette, Wyoming.

Related link:

Powder River Coalbed Methane Information Council

Powder River Basin.org">

9/11 Contrails

CURWOOD: You probably remember the eerily quiet and clear skies of September 11th. For three days following 9/11, all commercial air traffic in the United States was grounded. And except for military flights, the sky was free of airplane contrails.

Contrails are those long white cloud-like plumes that jet engines leave behind. David Travis joins me. He’s an atmospheric scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, who studies contrails and how they affect weather.

So Mr. Travis, as horrible as the events of September 11th were, they did give you a chance to check your contrail theories in the real world.

TRAVIS: You know, it’s not the way we wanted this opportunity to come about, obviously. And, I was even a bit hesitant to get into it initially. But, we figured this was the only time, we hope this will be the only time, this sort of thing ever happens.

And, it’s also sort of a convenient coincidence for us that we had rather fast weather patterns across the country during those few days. We had periods of clear skies. September 11th, for instance, was really unusually clear. And then following September 11th, we had increasing cloud coverage and moisture on the 12th and the 13th across the east. And this allows us to take out the argument that changes in the temperature range were simply a function of the weather patterns occurring. There was no persistent one type of weather pattern, either completely sunny or completely cloudy for three days. And that really helped.

CURWOOD: Now, how did you use this aircraft shutdown to figure out how contrails affect our everyday weather patterns?

TRAVIS: Well, what we’ve been doing for the last ten years or so is publishing a series of papers, and doing a series of research projects, and investigating the effects of contrails in a variety of ways. There have been studies that have done modeling types of analyses where we go and we look at contrails, and try to predict what kind of affect they would have. We’ve also used a variety of other circumstantial evidence types of arguments to basically point out that we believe that jet contrails, especially as their coverage increases, could be affecting the temperature range, just like what natural clouds do.

Basically, natural clouds, during the daytime block out sunlight. And at night, they trap the outgoing radiation. So they keep it cooler during the day, and they keep it a little warmer at night. And we’ve been arguing for a while now that jet contrails are enhancing that effect.

CURWOOD: So what did you find when you looked at the weather records for those three days in September?

TRAVIS: Well, we first started looking at satellite imagery to confirm our suspicions that there was a notable decrease in cloud coverage. And, we began initially studying that. But we decided to turn our attention more directly to the surface temperature observations. And we looked at about 4000 weather stations around the United States. And, we found, immediately, that we noticed an increase in the daytime temperature, most notably, for those three days across the country and a slight decrease in the nighttime temperature.

So in essence, we did see that there was an unusual increase in the temperature range. And we compared that to see how unusual it really was. Because of course, we get random variations in weather patterns all the time. And it could have easily been explained by that. We found that, indeed, the temperature range was the largest during those three days than we had seen in the past 30 years.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about some of the regional differences you must have seen.

TRAVIS: We speculated that, if jet contrails were really having an impact, we would see these changes the greatest in places where aircraft coverage is most frequent and specifically where contrails are most prevalent. And that’s places like the Midwest, the Northeast, and even the Pacific Northwest. These are areas where we get a lot of air traffic. But, the airplanes are not necessarily flying in and out of hubs a lot. They’re actually at cruising altitude above these areas where they’re a lot more likely to produce contrails. And what we found was, indeed, the temperature range increase was more than twice as large in these areas as it was for the rest of the country.

CURWOOD: Now, what difference does a degree or two make, do you think?

TRAVIS: Well, I know to the average person, and even myself, sometimes when I’m dealing with this data, and I see that there are changes of a magnitude of only 1 degree Celsius, or 2 degrees Celsius, in various studies I’ve done, initially, it sounds like it’s not very much.

But you have to remember a couple of things. One is that we’re looking at a change against 30 years worth of data. So, we’re not looking at simply a change that happened over those couple days, but we’re comparing it to the average over the past 30 years. And we’re also looking across a very large expanse. We’re looking across the entire United States. And so, a 1 to 2 degree Celsius change, which is basically the average of what we found in the temperature range, is actually quite substantial. And so, there are a variety of affects out there where we see reducing the temperature range as being a negative thing on natural ecosystems.

If you look at a lot of the global warming modeling studies that have been done, and those that are predicting huge increases in global temperature, and the ramifications that these increases are going to have on sea level rises, and so on, most of them are projecting just a few degrees increase in Celsius. So we’re not too far off in that effect.

[MUSIC: L’ALTRA, "Traffic," IN THE AFTERNOON (Aesthetic – 2002)]

CURWOOD: David Travis is an atmospheric scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater. Thanks for taking this time with us today.

TRAVIS: My pleasure.

Related link:

Dr. Travis’ webpage with a link to the research paper

A contrail page from NASA">

Health Note: Brains on Estrogen

CURWOOD: Coming up, why dealing with drought is a perennial problem in the U.S. Southwest. First, this environmental Health Note from Jessica Penney.

[THEME MUSIC]

PENNY: A new study suggests that as women age, their brains might be developing different ways of thinking. That’s because researchers at the University of Illinois say that estrogen, or the lack thereof, may dictate what strategy the brain uses to solve problems.

The scientists took young female rats and removed their ovaries so they would produce no estrogen of their own. They gave half of these rats estrogen injections, and left the others estrogen-free. Then they compared the two groups’ abilities to find food in two different mazes.

In maze one, the food was always in the same place. But the rat started at different points in the maze each time, so they had to travel in different directions to find the reward. In maze two, the food moved around, but the rats always had to make a right turn to find it. The rats with no estrogen did better in this maze. But the rats with estrogen were much better in the maze where the food was always in the same place.

The scientists think the hormone may alter particular regions of the brain, giving an edge to some ways of problem solving, while hindering others. If this study is applicable to women going through menopause, it may show that while some of their problem solving abilities can deteriorate, other abilities may be strengthened. That this week’s Health Note. I’m Jessica Penney.

[MUSIC UNDER]

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Air, "Playground Love," VIRGIN SUICIDES (sndtrk) (Astralwerks – 2000)]

Related link:

Press Release on this research">

Almanac: Yard Sales

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: Stuart Crombie & Dennis Berry, "Bargains Galore," MUSIC FOR T.V. DINNERS (Scampe/Caroline – 1997)]

CURWOOD: Summer is a comin’ in. And that means yard sales are sprouting up like wild daisies along the roadside, as all those extra widgets and knickknacks make their way out of dusty attics and onto freshly mowed lawns. If you go, make sure to take lots of water and towels to clean off potential buys.

That advice comes from Jeffrey Hood, who’s been bargain hunting for the past 13 years and has furnished his entire house with yard sale finds.

HOOD: My house has been described as a cross between an Egyptian temple and Pee Wee’s Playhouse. It’s a real mixture of things from various eras. But, a lot of them are one-of-a-kind pieces and they were just right on the side of the road.

CURWOOD: Mr. Hood says he found most of his collection at the world’s longest yard sale.

HOOD: It’s like my Christmas. You live for it all year long.

CURWOOD: That’s right. Down south, come August 15th, there will be some 3000 vendors offering treasures and trash along a 450-mile stretch of Highway 127, between Covington, Kentucky and Gadsden, Alabama. There will be tents and tables packed with everything from tractors to church windows, to brass beds.

One year, there was even an entire row of used kitchen sinks. So, go ahead and hit the road. And if you look long enough, veteran yard saler Jeffrey Hood says you might find your own Holy Grail of hand-me-downs.

HOOD: Somebody is going to come across that one thing that’s really, you know, the masterpiece out there, just waiting to be found. So, that’s part of the allure.

CURWOOD: And, for this week, that’s the Living on Earth Almanac.

[MUSIC UNDER]

Related link:

450-mile-long Highway 127 yard sale">

Southwest Drought

CURWOOD: Whiskey is for drinking, and water is for fighting. Or so the saying goes in the American West; especially in periods of drought like today’s. Three years of subnormal snow and rainfall in the Southwest have turned cities, states, and advocacy groups into bitter contenders, scrapping over a shrinking water supply. Ken Shulman has this report from New Mexico.

[SOUND OF TRACTOR]

SHULMAN: Corky Herkenhoff rides on the back of a tractor as a worker seeds one of his fields. Herkenhoff is a third-generation farmer in San Acacia, New Mexico, a desert region about 60 miles south of Albuquerque. His 700-acre property looks like a fuzzy green carpet sample, sewn onto a stretch of dusty burlap. Herkenhoff’s primary crop is alfalfa that he sells to local dairies.

HERKENHOFF: A stand of alfalfa can last you anywhere from about six to ten years. But it also costs about $200 an acre to establish a stand of alfalfa. And if we were to plant it now and to run out of water in 30 or so days and lose that investment, it’d be a little hard to get back.

SHULMAN: Herkenhoff’s water worries are very real. He gets his irrigation water from this 1938 diversion dam on a section of the Rio Grande that borders his property.

HERKENHOFF: Welcome to the mighty Rio Grande. It’s not very mighty right now.

Corky Herkenhoff farms in San Acacia, New Mexico.

SHULMAN: The tan, trim, 61-year-old farmer smirks beneath his baseball cap, then turns and gestures towards the bare mountains to the north. It’s been a bad winter for skiers, he says. And that means a bad summer for farmers.

[SOUND OF RIVER]

HERKENHOFF: Normally, we’d have, at this time of the year, probably 3000 cubic feet per second going by the dam here. And right now, I’d guess we’ve got less than 100.

SHULMAN: And as New Mexico water dwindles, the number of people using it continues to grow. There were fewer than 200,000 people living in New Mexico when Herkenhoff’s ancestors moved to San Acacia at the turn of the 20th century. Today, the state counts nearly two million inhabitants. Right now, 85% of New Mexico’s water goes to agriculture. But most New Mexicans don’t farm these days. They live in cities like Santa Fe, or in suburban developments, drawn by the climate, by cheap real estate and by the abundant rainfalls of the 1980s and ‘90s.

[SOUND OF BIRDS, CAR DRIVING]

But take a walk along the Santa Fe River in downtown Santa Fe, where the only audible flow is the flow of traffic. Residents of the city are trying to conserve water by putting bricks in their toilets. They watch as their lawns turn from green to brown.

Tom Turney is state engineer for New Mexico. He says that the current drought shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone.

TURNEY: A lot of people thought that it was just unlimited amounts of water. There were a lot of people that came here from out of the state and they didn’t realize that this state is basically a semi-arid state.

SHULMAN: Historians, geologists and scientists will tell you that drought is a natural and recurring phenomenon in the Southwest. So too, it appears, is migration. And there’s evidence of this just 20 minutes south of Santa Fe.

[SOUND OF HIGHWAY]

SHULMAN: San Cristobal Pueblo is an abandoned settlement in the Galisteo Basin, just off the old Las Vegas Highway. In the 13th century, a severe drought to the north drove the Tano Indians here. For the next 300 years, an unusually favorable climate allowed the Tano to plant corn. Then, the rains failed.

Today, San Cristobal Pueblo is little more than three unexcavated mounds straddling a dry arroyo. Rock faces on the nearby hill bear carved images of corn plants, farm animals and the sacred Tano water serpent.

Eric Blinman is an archaeologist with the Museum of New Mexico. He says these Tano petroglyphs were meant to bring rain.

BLINMAN: In one particular almost poignant case, a corn plant has been carved into the rock face directly above a sandstone pool that collects and holds water after every rain and can hold water for weeks.

SHULMAN: Neither the Tano petroglyphs, nor the Tano faith, could keep the Galisteo waters from drying up. Weakened by drought and famine, the Tano were left exposed and vulnerable when the Spanish conquered the area in the 16th century.

Dam on the Rio Grande.

Blinman acknowledges that modern technologies, like dams and reservoirs, provide cities like Santa Fe a survival buffer that the pueblo dwellers didn’t have. But he worries that contemporary New Mexicans may be just as vulnerable to a period of extended drought as the Tano were.

BLINMAN: In fact, when you look at Santa Fe’s history in a contemporary landscape, there was more stability laid out in front of us a millennium ago than there is in Santa Fe today.

SHULMAN: One thing the Tano didn’t have to worry about was lawsuits. Courts in the Southwest are jammed with water litigation: suits between farmers and municipalities, suits between New Mexico and Texas, suits between the United States and Mexico and suits between environmental groups and the U.S. government.

One of these suits, Minnow vs. Martinez, could force New Mexico to release stored water to help preserve the endangered Rio Grande Silvery Minnow. If this happens, municipalities, industry and especially agriculture will suffer.

Stephen Farris is director of the Environmental Enforcement Division for the New Mexico Attorney General. He says water is the fastest lawsuit in the West right now.

FARRIS: When I first became a water lawyer, nobody, even in New Mexico, they didn’t really know what it was. Now everybody knows what a water lawyer is, and it seems like every lawyer claims to be one. But it’s because of its increasing economic importance, I think. And that has come about because there’s increasing demands, both human demands and environmental demands. But there’s no more water.

[SOUND OF BALE LIFTER]

SHULMAN: Back at San Acacia, Corky Herkenhoff operates a diesel-powered bale lifter, hoisting eight bales of alfalfa hay onto a customer’s flatbed truck. Like most farmers, Herkenhoff has senior water rights. When water is in short supply, these rights give him priority over other users. And he’s not willing to give up those rights, to anyone, for anything.

HERKENHOFF: For somebody to come and say, "Well, we’re taking your water because we need it for the minnow, or we need it through the municipalities," they can’t do that in this state. And it would be no different than somebody coming up to you, Ken, and saying, "We’re going to take your car because we think we have a better use for it." But they can’t do that.

SHULMAN: It’s possible, but not very likely, that New Mexicans will have to choose between farming, fauna and flushing. More likely is that state authorities will have to be increasingly creative in managing their water. They’ll also have to be more vigilant. Until now, no one has ever monitored the amount of water that farmers like Herkenhoff draw from the Rio Grande. Unless it rains, and rains heavy, they’ll probably start counting every drop. For Living on Earth, I’m Ken Shulman in San Acacia, New Mexico.

[MUSIC: Marc Ribot, "Aurora En Pekin," MARC RIBOT Y LOS CUBANOS POSTIZOS (Atlantic – 1998)]

Picky Pig

CURWOOD: Many families with 12-year-olds are beset with finicky eaters. And so is our commentator, Sy Montgomery. Although, you might say her problem is of behemoth proportions.

MONTGOMERY: I have an embarrassing and, you might say, oxymoronic dilemma. I have a picky pig.

[SOUND OF PIG GRUNTING AND BIRDS]

MONTGOMERY: Meet Christopher Hogwood, named in honor of the famous conductor. Twelve years ago, when I carried Christopher home from the piggery in a shoebox, he weighed seven pounds. Today, he weighs 750 pounds. And a 750-pound pig eats as much as he can. Satisfying such an appetite is hard enough in normal times. But, recently, Christopher’s palate has gone particular.

These days, he demands only the finest puff pastries, imported cheeses and homemade pasta. It didn’t used to be this way. Once, just like other pigs, Christopher Hogwood relished rotting pumpkins and green pepper innards. He would plunge, with abandon, into heaps of deliquescing produce, delighting equally in spoiling bananas, decaying broccoli stems, carrot peelings and melon rinds.

When visitors would ask, "Can we bring anything?" I’d say, "Sure, your garbage." But that was before the ice storm of 1998. Much as been written about the destruction brought on northern New England by that mighty tempest. It knocked the electricity out for days in my little town. And the melting contents of Hancock, New Hampshire’s best-stocked refrigerators and freezers made their way towards his sty.

Day after day, the bounty mounted. Sure, we still got banana peels and celery stalks. But now, people were bringing melting pints of Ben and Jerry’s ice cream, raspberries in syrup, brie and camembert wrapped in filo dough, entire lasagnas, sourly chocolate cakes, slabs of smoked fish and tubs of crème fraiche.

Christopher Hogwood exercising his discriminating palate.

Soon, Christopher Hogwood was in hog heaven. And before long, he was literally spoiled rotten. He had more pig junk food than he could eat. He knew it. And now everybody in the barnyard knows it, too. The chickens, who he used to chase away from his food with a grunt and a swipe of his tusks, now freely forage his bowl for food scraps, like mushroom stems, once relished, now disdained. Formerly cherished cabbage heads are now tossed to the dog like toy balls. And when friends and neighbors drop off a bucket of old leek tops or a bushel of overripe corn, we don’t have the heart to tell them it all goes straight to the compost heap now. Christopher Hogwood won’t even look at cornhusks anymore. These days, our picky pig prefers his corn buttered. So, thank God for Fiddleheads Cafe.

[SOUND OF CAFÉ]

MONTGOMERY: The gourmet eatery on Main Street saves their leftovers for Christopher. And I pick them up on their back porch -- daily, of course. It must be fresh. Lift the lid from one of their five-gallon plastic slop buckets and out wafts the scent of balsamic vinegar. Today, a homemade pasta salad with imported olives and cheeses, bathing in marinade, will grace our pig’s plate.

[SOUND OF PIG EATING]

MONTGOMERY: On Sunday afternoons, we get all the leftover pastries, poppy seed and blueberry muffins, cinnamon rolls and lemon danish. My husband and I go to weddings and receptions in town, only to realize that our pig and we are eating off the same menu. Except for the pig, the presentation is slightly ajar. The spanakopita triangles are floating in the dip. And the strawberries are piled on top, perhaps capped with a stale bagel.

But, our picky porcine doesn’t mind. He’s made his desires known. We simply obey. And for that, he rewards us with the jolly and uplifting spectacle of behemoth greed, satisfied, at least for now.

[SOUND OF PIG EATING]

CURWOOD: Oh my. Christopher Hogwood dines at his sty in Hancock, New Hampshire where he lives with our commentator Sy Montgomery, her husband Howard, Tess the dog and chickens that have no names.

[MUSIC: Glenn Miller & Tex Beneke, "Booglie Wooglie Piggly," (TEXAS TEX)]

Traditional Medicines

CURWOOD: You’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth. The World Health Organization has just released the first global strategy to monitor and protect traditional and herbal medicines. The Organization plans to catalogue thousands of treatments and evaluate how well they work. Joining me is Dr. Jonathan Quick, the director of Essential Drugs and Medicines Policy at the W.H.O. Dr. Quick, tell me, why the focus on traditional and herbal medicines now?

QUICK: It’s really a response to the trend of this increasing use in herbal products. And then, globalization has brought concerns about the heritage of traditional knowledge in medicinal plants with some of the traditional healers growing old. And if they’re not passing on their knowledge, it can be lost.

CURWOOD: As part of your strategy, as I understand it, you’re going to catalogue. You’re going to compile information on these various traditional and herbal treatments. How do you go about evaluating the efficacy of these treatments?

QUICK: Well, for many of these treatments, there exists a long history. But there also exists quite a bit of published research, and it varies greatly. So where the data exists, we want to bring it together and make it available for people. Where the evidence doesn’t exist, then we want to try to stimulate research.

CURWOOD: You’ve expressed some concern that traditional knowledge might be lost. How does the World Health Organization plan to respond to these concerns?

QUICK: One is on the medicinal plants themselves, developing good agricultural practices so that there are standards and guidelines on how to preserve the plants. The second is in the area of making the knowledge available on the different alternatives that countries have for protecting the knowledge. There has been so-called bio-piracy where companies have come in and patented a plant. So what some countries are doing -- India, for example -- is establish a traditional knowledge digital library. They put the information in the public domain. And that makes it effectively unpatentable and keeps it available for people.

CURWOOD: What kind of opposition, if any, have you run into in trying to deal with traditional healing and medicine?

QUICK: The enthusiasts basically believe that natural therapies are invariably safe and effective. And, the skeptics basically believe nothing but modern medicine works. Not surprisingly, the reality is somewhere in between. And that’s really what we’re trying to bridge, is this gap between the enthusiasts and the skeptics.

CURWOOD: Dr. Jonathan Quick is director of Essential Drugs and Medicines Policy at the World Health Organization. Thanks for taking this time with us today.

QUICK: Pleasure to be with you. Thank you.

[MUSIC: In Be Tween Noise (Steve Roden), "Etarpoave," HUMMING ENDLESSLY IN THE HUSH (New Planet Music – 1995)]

Related link:

Press Release on W.H.O. project">

Tech Note: Virtual Help for Parkinson’s

CURWOOD: Just ahead, your letters. First, this environmental Technology Note from Cynthia Graber.

[THEME MUSIC]

GRABER: People who suffer from Parkinson’s disease tend to hesitate and stumble when they walk. Now, a new virtual reality device may help them move more easily through their environment. Previous research revealed that Parkinson’s patients walk better on tiled floors. That’s because the sharp edges and lines are easy to see. Tiles also encourage patients to stretch their legs further, and pick them up to reach the next block.

So Dr. Yoram Baram, at Israel’s Technion University, used this information to design a virtual tiled floor. He took a pair of eyeglasses and attached a tiny computer screen to the rim so that it hangs in front of one lens. A computer displays an image of a tiled floor to the screen. When a person takes a step, sensors in the glasses pick up the movement and the virtual tiles on the screen move as if the person were actually walking along a real tiled floor.

The virtual image is small enough that it doesn’t impede the patient’s overall vision. Dr. Baram conducted a study with 40 patients. He found that their speed and the length and stability of their stride improved by an average of 25 to 30%. That’s this week’s Technology Note. I’m Cynthia Graber.

[MUSIC UNDER]

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Earnest Woodall, "128 Details from a Picture," PICTURES IN MIND (Zephyrwood Music – 2002)]

Related link:

Article about the virtual tiles">

Listener Letters

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. And coming up, some smell cow manure, others smell money, as the dairy business booms in Idaho. But first –

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Time for comments from you, our listeners.

WAMU listener Michael Colopy called us from McLean, Virginia with praise for our story on the environmental hazards of fish farming.

COLOPY: I thought Cheryl Colopy, who, by the way, is no known relative of mine, did a superb job. And, I think this particular topic, the threat to native fish in our rivers, is one that was very well featured. And I’m hoping that you’ll do more stories of this kind.

CURWOOD: Well, Mr. Colopy, we certainly will. Bob Carty’s Generation Next series about science influencing human evolution has been generating plenty of listener interest. Ike Sanderson hears Living on Earth on KLCC in Eugene, Oregon and writes that he loves the series.

"I teach Biology at a public school in Eugene and used the Xenotransplantation episode as a focus during one day’s activities. The piece stimulated a lot of thoughtful discussion. And kids had their preconceptions challenged. Great job."

Many listeners appreciated our report about Germany’s new laws governing living conditions for egg-laying hens. Maine Public Radio listener, Bob Lodato, praised Michael Muhlberger’s report. He writes, "Your story was unbiased and objective, two reasons it’s going to be effective at arming the average person’s intellect for combating this very dark aspect of the animal food industry. I have always enjoyed your show. And now I am teaming with admiration and good wishes."

Well, we’ll take your kudos anytime on our listener line. The number is (800) 218-9988. Our email address is letters@loe.org. And, visit our web page at www.loe.org. That’s www.loe.org.

[MUSIC UNDER]

New Dairies

CURWOOD: Urban sprawl is often blamed for pushing the family farmer off the land. City folk move in, then suddenly realize their pastoral dreams don’t jive with how their noses respond to farm animals. Tempers flare, regulations multiply and, more times than not, farmers move on. Many dairy farmers have left California, and come to the Magic Valley of southern Idaho. They hope there will be fewer headaches from neighbors in this sparsely populated patch of high desert. But as producer Guy Hand has found, attitude and size make all the difference when it comes to cows and people sharing the land.

HAND: Dairyman, Dean Swager, remembers what it was like growing up in the Chino Valley, 40 miles east of L.A.

SWAGER: You could count the cars that went by on two hands everyday. But now, anymore, it’s very, very busy. There is a dairy every thousand yards. So, our fence line bordered another dairy fence line which had cows. The cows could touch each other between property lines.

HAND: Hemmed in by development, Chino Valley dairymen found themselves trapped on a shrinking agricultural island. That part of California now contains the highest concentration of cattle in the world. And with that comes problems.

SWAGER: Well now they’re putting all these new rules down and nobody can comply. And it’s getting very hard in order to get rid of your waste. You end up trucking it wherever you can find a place to put it. It’s becoming very difficult.

HAND: So Swager and his young family pack their bags and join the dairy exodus to Idaho. In October of 2000, they settled in the Magic Valley. Despite the name, it’s a dry, treeless plain that was passed on by early pioneers. Irrigation brought a smattering of small farms and ranches. But today, it’s still a place where Swager can count the cars that go by on two hands.

[SOUND OF COW MOOING]

HAND: But the dairymen who blazed the trail from L.A. to Idaho a decade ago are finding that their problems followed them to the Magic Valley. Former Californian Andrew Jarvis manages a dairy of about 2.400 animals just west of the small town of Buhl.

JARVIS: So, when we first moved here ten years ago, there wasn’t a whole lot of real negative publicity against dairies. But, it started about two years after we moved here.

HAND: As the dairies in southern Idaho multiplied, people began complaining about odors, water pollution, traffic, blaring lights and more, just like California.

JARVIS: It’s a little bit frustrating. It seems like we’re always in the corner getting knocked down. And it’s unfortunate because everybody needs to eat.

HAND: Like many transplanted dairymen, Jarvis thinks those complaining just don’t understand what it takes to make food.

[SOUND OF PEOPLE TALKING]

HAND: But that’s where the story gets complicated. Many Idahoans know all about what it takes to make food.

HOKE: My grandfather was a dairyman. My uncles are dairymen.

HAND: Idaho native Marilyn Hoke, her husband and a few neighbors are standing in her front yard, just downwind from two newly-transplanted California dairies.

HOKE: I grew up on a dairy. I’m not afraid of the smell of cow manure.

HAND: But these new dairies aren’t like anything she’d seen or smelled before. Not the two- or three-hundred-head operations she grew up with, these dairies contained well over 10,000 cows. She says they’re factories, not dairies. And they’ve made the neighborhood unlivable. Marilyn’s husband, Robert.

ROBERT HOKE: The smell here, sometimes -- well, it used to be I’d sleep with my windows open at night. You can’t anymore. Because you wake up in the middle of the night nauseated.

HAND: Former neighbor, Sena McKnight, who has since moved to get away from the dairies.

McKNIGHT: We used to sit on the front porch step and watch the sunset go down. And we quit because we would just be swarmed by odors, flies, dust from the cows, dust from the traffic.

LYMAN: I’ve actually come out of my house and gagged and turned around and went right back in because it’s so bad.

HAND: Neighbor Bob Lyman.

LYMAN: People shouldn’t have to live like this.

HAND: After nearly a thousand complaints were recorded in the summer and fall of 2001, on one dairy alone, Idaho’s regulatory agencies began to take notice. The Idaho Department of Environmental Quality started measuring the amount of hydrogen sulfide emanating from local dairies. Tim Teater is the Air Toxic Program analyst for the agency.

TEATER: And at the levels that we’re seeing, they would generally lead to eye irritation, throat irritation, coughing, difficulty breathing. If you have reactive airway disease like, for instance, if you’re an asthmatic like I am, a lot of times if you have elevated levels of hydrogen sulfide that can cause your asthma to worsen.

HAND: Readings taken by the department at one dairy property line registered 33 times the hydrogen sulfide levels suggested as safe by a recent study.

TEATER: It’s an interesting phenomenon that the complaints that we receive oftentimes come from people that lived in the areas for many, many years that have been farmers and ranchers and come from farming and ranching communities.

HAND: What’s fueled this trend towards factory farming in southern Idaho is, in part, the very urban encroachment on family farms that we’ve all heard about. As property values rose in places like Chino, California to $70 or $80,000 an acre, dairymen cashed out, and moved to far cheaper, less regulated land. In Idaho, it’s allowed them to build much larger dairies. So in the Magic Valley, it’s not suburbia that’s pushing hard against traditional, rural life. It’s this new, super-sized agriculture.

LEDBETTER: If we could all wave our wands and go back to everybody being able to make a living off of 160 acres, it would be wonderful. But, I mean, that’s just not reality anymore.

HAND: Greg Ledbetter is a California veterinarian turned Idaho dairyman.

[SOUND OF MACHINERY]

Greg Ledbetter is a large dairy operator who believes that technology can solve the industry’s problems.

LEDBETTER: When people say, "Well gee, why are you milking so many cows?" I ask them, "How many of you would want to go back to milking 100 cows? And you’re going to milk those cows twice a day, 365 days a year, for $20,000." And the answer is, nobody in their right mind would do it.

HAND: Ledbetter puts his faith not in a return to smaller farms but into better management and more sophisticated technology. And that means dealing with manure. Since the dairy boom, some Magic Valley counties have seen close to 150 percent increase in animal waste. Still, Ledbetter is optimistic. He’s seen the Idaho dairy industry solve big problems before.

LEDBETTER: Seven years ago, there was nearly 50% of the dairies in this state that were discharging daily to various rivers and streams. Within three years, we had virtually 100% of those dairies cleaned up.

HAND: To stop animal waste from polluting rivers and streams, Idaho dairies built lagoons to hold manure until it could be composted or sprayed on cropland as organic fertilizer. Yet, their attempts to solve one problem led to another.

LEDBETTER: As soon as you start storing organic waste, and large volumes of it, you’re going to have bacterial breakdown that’s going to produce the odors. Our responsibility is to eliminate those odors. Anaerobic digestion may be one answer. Ozone treatment may be an answer. There may be other technologies out there that we don’t know yet. But we’ve got to find them. And we’ve got to find them quickly, in my opinion, if we’re going to continue to exist here in this state.

HAND: Ledbetter’s sense of urgency is understandable. Angry Magic Valley residents have filled town halls and legislative hearing rooms, demanding tighter restrictions on existing dairies, and moratoriums on building new ones.

Despite this opposition, Ledbetter is quick to point out that big dairies are a big boon to Idaho’s economy. Milk has replaced the famous Idaho potato as the state’s number one agricultural commodity.

LEDBETTER: It’s just incredible. As you start adding up the businesses in this little town that are there because the dairies are here, it’s a huge economic impact. These towns are vibrant again because the dairy industry’s been here.

HAND: Yet, a recent nationwide study of factory farms found they actually generate less state and local revenue per animal than do smaller operations.

Bill Stolzfuz sees other advantages in staying small. So, how many head of cattle do you have here?

STOLZFUZ: There’s about 85 milk cows, milking and dry.

HAND: A dairyman who fled Pennsylvania’s urban growth, Stolzfuz didn’t expand his dairy after settling in the Magic Valley.

[SOUND OF MACHINERY]

STOLZFUZ: They all have names.

HAND: Your milk cows have names?

STOLZFUZ: Oh, yeah. Everybody has a name. And they’re all individuals.

HAND: Stolzfuz introduces me to his Holsteins.

STOLZFUZ: Well, the first one is Bobbi and the second one is Sassy and the third one is Muffin.

HAND: Because he has a small herd and lets them graze on pasture in the summer, he has few waste problems. And he doesn’t push his cows to the limits of production like big operators. As a result, they live far longer than the average of three or four years for cows in the mega-dairies.

[SOUND OF WALKING]

STOLZFUZ: This cow is, Mindy is her name. She’s 12-years-old right now. And in a few months, she’ll go over 300,000 pounds of milk, lifetime. And still working away.

HAND: Despite, or maybe because of, his close relationship to his cows, Bill makes a comfortable living. And he’s had no complaints from neighbors about odors or anything else.

STOLZFUZ: I think we have an efficiency that some of the big operations can’t match, as far as our individual attention to details. And I have no problem with large operations, if they’re run well and managed well. But big just for the sake of big is not good.

MIDKIFF: I got almost 3,000 miles on my car since I left home.

HAND: Ken Midkiff does have a problem with large agricultural operations.

MIDKIFF: The problem here is you’ve got just too many cows in one place.

HAND: He’s the Sierra Club’s national expert on factory farms. He’s seen manure lagoons and other agricultural fixes fail all over the country, flooding into rivers and wetlands, seeping into groundwater.

With help from local activists Lynn Miracle and Bert Redfern he’s touring the Magic Valley, looking for federal clean water violations.

[SOUND OF TALKING, BIRDS SINGING]

HAND: As the group passes dairy after dairy, Midkiff sees in southern Idaho what he’s seen in industrial dairy, hog and chicken farms all over America.

[SOUND OF DRIVING]

An anti-big dairy bumper sticker in the Magic Valley.

MIDKIFF: This really has nothing whatsoever to do with providing milk, or meat, or whatever we’re talking about, to a hungry world. What this is about is market control. It’s the attempts of a few big companies to control the meat, milk and egg markets.

HAND: Midkiff sees a very different story here than one of displaced farmers merely escaping urban sprawl.

MIDKIFF: A lot of them had to leave the Chino Basin because the California Water Quality Board really cracked down on them. And they were subjected to a bunch of regulations. So they’re really out looking for places where the regulations are either nonexistent or unenforced, such as in the Snake River Plains of Idaho. They’re pollution shopping. They’re looking for places where they can get away with contaminating the air and water, fouling the land and running family farmers out of business. I mean, that’s really what this is all about.

HAND: Lynn Miracle taps on the window, pointing to a vacant house they’re passing by.

MIRACLE: Here’s my son’s place that they bought out. The dairymen sent him a check from Chino, sight unseen, and essentially to get rid of him.

HAND: Some dairymen have simply bought out their most vocal critics. But as real estate prices plummet around large dairies, most homeowners are left trapped in houses no one will buy. In fact, many of the Valley dairymen themselves choose to live outside the area.

MIDKIFF: I mean, at some point, it just reaches a size where it’s impossible to manage in a way that’s not offensive. Either we’re going to have odor, flies or they’re going to foul the waters.

[SOUND OF TALKING]

HAND: Soon, we find a source for all three. We pull off the road and get out of the car and walk toward what looks like a small mountain perched above the creek. Lynn Miracle.

[SOUND OF WATER FLOWING]

MIRACLE: Well, you’re seeing a huge pile of dairy manure, poised on the very bank of Deep Creek, which is one of our major drainages here. And it’s all going to be all in Snake River in another five or six miles, or less.

HAND: Nitrate levels in the Valley’s water supply are rising, although government regulators are reluctant to blame the dairy industry. Still, it’s another worry angry locals add to a growing list. Bert Redfern.

REDFERN: When we moved to the country 30 years ago, we thought it was the most clean, wholesome, healthy lifestyle. Twenty years later, we have to purify our water. Talk to a large dairyman, and he’ll tell you that we’re just overly sensitive and that we’re urbanites that have moved in on them. But, that’s not what’s happening here.

[SOUND OF WATER FLOWING]

HAND: American agriculture has long teetered between two distinct and often contradictory ideologies. The first is pastoral, embodied by Thomas Jefferson and a land dotted with small family farms. The second is industrial, embodied by Henry Ford, the assembly line, high technology and economies of scale. This divide is the one that separates organic farming from genetic engineering and a dairy of 50 cows from a dairy of 5,000.

Here, on the banks of Deep Creek, you only have to sniff the air to tell which way the agricultural wind is blowing.

MIDKIFF: That smells like cow manure to me. But a dairy person would say that smells like money.

HAND: For Living on Earth, I’m Guy Hand in Idaho’s Magic Valley.

[MUSIC: Earnest Woodall, "Bohemia Lies by the Sea," PICTURES IN MIND (Zephyrwood Music – 2002)]

Related link:

University of Iowa study on the environmental and cultural effects of factory livestock farms

Idaho's Dairy Initiative">

CURWOOD: And for this week, that’s Living on Earth. Next week, the cyborg society. Many futurists say computers and technology will someday be able to outthink and outperform humans. So some scientists are trying to stay a step ahead by slowing turning the body into a machine, using chip implants and high tech mechanical parts.

MAN: I don’t want to be a human anymore. I would like to be a cyborg. I would like to have extra capabilities. And the research we’re doing is pushing in that direction, upgrading humanity.

CURWOOD: It’s the marriage of man and machine, when our series "Generation Next: Remaking the Human Race" continues, next week on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC UNDER, SOUNDS OF RAIN, BIRDS AND STAGS]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week with a hard rain falling on the edge of a forest in Glenn Affric, Scotland. In the distance, listen for the mournful croon of stags. It’s an appropriate sound for this early October recording by Chris Watson, entitled "The Forest Path."

[Chris Watson, "The Forest Path (Stags)," STEPPING INTO THE DARK (EarthEar – 2002)]

Living on Earth is produced by The World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at www.loe.org. Our staff includes Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Maggie Villiger, Jennifer Chu, and Al Avery, along with Peter Shaw, Leah Brown, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson and Milisa Muniz.

Special thanks to Ernie Silver. We had help this week from Rachel Girshick and bid a fond farewell and bon voyage to our globetrotting intern, Jessica Fenn. Thanks, Jessie. Allison Dean composed our themes. Environmental sound art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our technical director is Dennis Foley. Ingrid Lobet heads our western bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor. And Chris Ballman is the senior producer of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood, executive producer. Thanks for listening.

WOMAN: Funding for Living on Earth comes from The World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, for coverage of Western issues; The National Science Foundation, supporting environmental education; and, The Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living on Earth’s expanded internet service.

MAN: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth