November 15, 2002

Air Date: November 15, 2002

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Rivers South, Part 1

/ Clay ScottView the page for this story

Reporter Clay Scott takes us down the Chattahoochee River. The river begins in Northern Georgia and makes its way south to Florida where it ultimately empties into the Gulf of Mexico. Along the way, the Chattahoochee runs through Atlanta where a growing population, and the drought, are putting pressures on the river’s ecoystems and the livelihood of fishermen further downstream. (13:00)

The Rivers South, Part 2

/ Clay ScottView the page for this story

We continue our journey down the Chattahoochee, where the river changes names and character. Clay Scott reports. (13:30)

News Follow-up

View the page for this story

New developments in stories we’ve been following recently. (03:00)

Animal Note/Lizard Lounge

/ Maggie VilligerView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Maggie Villiger reports on a lizard species whose promiscuous females hold all the power in the mating game. (01:20)

Valles Caldera

/ Paul InglesView the page for this story

Two years ago, Congress bought 90,000 acres of scenic land in New Mexico and, in an unusual move, appointed an independent board to oversee it. As Paul Ingles reports, the board’s early decisions have made some environmental groups worried about what lies ahead. (07:30)

Fine Animal Gorilla

View the page for this story

A new music CD called "Fine Animal Gorilla" is based on the life of lowland gorilla Koko. She even contributed some of the lyrics using American sign language. Host Steve Curwood talks with Skip Haynes, one of the album's producers. (08:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodREPORTERS: Clay Scott, Paul InglesGUESTS: Skip HaynesUPDATES: Maggie Villiger

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR News, it’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The southeast is one of the wettest parts of the United States, so you might think people there have plenty of water. But population growth in Atlanta and its booming suburbs is putting so much pressure on the Chattahoochee River that folks are worried upstream and downstream.

GREEAR: Everybody lives on it. You have to think about the people below you and say, we’ve got some sort of obligation to send the water on and not to overuse and be selfish with it.

BLACKWELL: When it comes to people watering their lawns or a river surviving, it’s got to be the river survives, because that’s part of our world. And when you keep chipping away at our world, you’re just going to do away with people.

CURWOOD: The crunch on the Chattahoochee. And Koko the gorilla goes for a Grammy. That and more this week on Living on Earth, right after this.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

The Rivers South, Part 1

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The southeast part of the U.S. may be lush and green but it’s not exempt from growing demand for fresh water. And one place where water disputes are heating up involves the Chattahoochee River.

The Chattahoochee flows down from the mountains of north Georgia and through Atlanta. Along the way it provides water for drinking, crops, electricity and recreation. But development pressures in Atlanta are sucking the river dry and years of drought haven’t helped.

Politicians are struggling to find a way to share the water but they have yet to find easy answers. Producer Clay Scott begins our story at the source of the Chattahoochee in northern Georgia.

SCOTT: The Chattahoochee River rises in the mountains of north Georgia, in the southern end of the Appalachian range. I want to find its exact source but I need a bit of help. In the town of Helen, Georgia, I meet Delbert Greear, a 54-year-old math teacher and native of the mountains. He agrees to be my guide.

[TRUCK DRIVING OVER LAND]

SCOTT: A few miles north of town, Delbert eases his battered pickup onto a dirt road in the Chattahoochee National Forest. Leaving the truck at the trailhead, we begin to walk.

[WALKING THROUGH WOODS]

GREEAR: Cool little gap, isn’t it?

SCOTT: Oh yeah.

GREEAR: Blackberry bushes and the possible home of the old copperhead there ....

SCOTT: For an hour we climb the mountain known as Jack’s Knob. Delbert points out white and blackjack oak, sassafras and sourwood, poke bush and poplar. Stopping on a ridge top to catch our breath, a sudden mountain rain shower takes us by surprise.

[SOUND OF RAIN]

SCOTT: There’s no adequate shelter nearby but Delbert quickly builds a small fire.

[CHOPPING WOOD]

SCOTT: As we hunch over it for warmth, Delbert speaks of growing up in the headwaters of the Chattahoochee.

GREEAR: I have a specific liking for this neck of the woods. It’s in my bones and blood. Going down the river, you’ll see other people that see their particular neck of the woods as being the Garden of Eden or slightly removed, however slightly removed from it.

SCOTT: The narrow ridge we’re on divides the watersheds of the Chattahoochee and the Tennessee Rivers. Standing in a rainstorm in a forest of nearly tropical lushness, it’s difficult to remember a bitter conflict is being fought over the waters that originate here. Too many people, Delbert says, take that water for granted.

GREEAR: Everybody that lives on it, you have to think about the people below you and say, we got some sort of obligation to send the water on and not to overuse and be selfish with it.

SCOTT: Finally, the rain lets up. We make our way across a ravine to where a steady trickle of water flows from beneath a granite boulder.

[SOUND OF WATER FLOWING]

SCOTT: This is the spot where the Chattahoochee begins its 540-mile course. The water is cold, sweet and delicious with just a hint of mineral taste. We follow the flow down the mountain where the trickle comes together with another and another. Soon it’s become a full-fledged mountain stream, home to rare speckled trout. At this point, Delbert announces the Chattahoochee is a river.

[WATER FLOWING MORE FIERCELY]

SCOTT: Back in Helen, I meet Delbert’s father, Philip, a former farmer who late in life became a professor of ecology. After a supper of grilled steak and cornbread and beans, he invites me to the back porch to talk.

[CRICKETS CHIRPING AND A DOG BARKING IN THE DISTANCE]

SCOTT: Philip, who has lost his sight in recent years and much of his hearing, is passionate about the Chattahoochee, a love affair that started in 1936 when he and his brother decided to follow the river to the Gulf of Mexico.

GREEAR, P.: We wanted to go down the river. We had no purpose. We just wanted to go down the river. We had grown up here on it, it was our river and we knew that it went somewhere. So we built this pair of boats that became one boat. It’s two feet wide and 16 feet long, built out of one-inch thick, undressed lumber.

SCOTT: Fortified with canned pineapple juice, oatmeal and a slab of bacon, the Greear brothers set forth. They traveled at the speed the water flowed, about two miles an hour.

GREEAR, P.: The mathematicians will tell you that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. Our decision was that the longest distance between two points is a meandering river. [CHUCKLES]

SCOTT: That meandering river carried the two teenagers south for nearly 300 miles before exhausted, they abandoned their boat and hitchhiked home. Though the Chattahoochee was muddy, Philip said they fished and swam in its current, boiled its water for coffee and oatmeal, and helped themselves to watermelons growing on its banks. Today, the urban sprawl north of Atlanta has swallowed the watermelon fields and few people dare to swim in the river.

[BOAT ON THE RIVER]

BETHEA: You see trash, footballs, you see all kinds of other waste and debris that’s floated here off of the city streets and through the storm drains, right where we get our drinking water.

SCOTT: Sally Bethea is the director of the Upper Chattahoochee Riverkeeper, an organization that’s been leading the fight to clean up the river. She takes me on a boat tour through the heart of Atlanta. On our way, we pass three of the city’s over-taxed wastewater treatment plants, not far from where drinking water is being pumped out.

BETHEA: Just immediately downstream you can see Peachtree Creek. It’s one of the biggest tributaries to the Chattahoochee and also one of the most polluted.

SCOTT: The Chattahoochee below Peachtree Creek is one of the most polluted stretches of river in the country. Many of Atlanta’s antiquated sewer lines also carry stormwater, causing more than occasional overflows of the system.

In the 1990s the city paid $20 million in fines for improper treatment of sewage. Atlanta has been ordered to overhaul the system by 2007. But despite the bits of trash we see, I am struck by how isolated I feel in the middle of a city of four million. As we float past banks lined with sycamore and river birch, we startle wood ducks and mallards, kingfishers and blue herons. But there’s more to the Chattahoochee, says Sally Bethea, than meets the eye.

BETHEA: This river is still to me certainly a very beautiful river. It has many different kinds of faces. And the water doesn’t always look like there are problems with its quality. But I can tell you, after a heavy rainstorm, the e. coli level in this river is just off the charts. And it’s just an unacceptable level for a river that runs through a vibrant city like this. We’ve got to do better.

SCOTT: The pollution problem is critical, not only for the health of the river itself, but because Atlanta takes nearly all its drinking water from the Chattahoochee. It’s the smallest American river to supply so large a city. Atlanta sits on a hard bed of igneous rock without easy access to the underground aquifers that supply fresh water in many cities. And the city is growing by the day. In the past ten years, the population of greater Atlanta has jumped over 40%, from 2.9 to 4.2 million. Water consumption has kept pace, climbing from 320 million gallons a day ten years ago to well over 400 million. Within 30 years that number is expected to reach more than 700 million gallons per day, a figure, says Sally Bethea, that spells potential disaster for both the river and the city.

BETHEA: There is simply a limit to the amount of growth that can occur in metro Atlanta and be sustained by its rivers. This is a shallow river; it’s a river that can only provide so much drinking water and wastewater assimilation. The worst-case scenario is that in 30 years, where we’re sitting right now you’ll see nothing but a drainage ditch carrying away the waste of parking lots and sewer lines and sewer plants.

[SOUND OF CONSTRUCTION MACHINERY]

SCOTT: But Atlanta’s rampant growth shows no sign of slowing down. J.T. Williams has built thousands of homes in the greater Atlanta area. I interviewed him at the country club of one of his many gated communities.

[WATER SPRINKLERS TURNING]

WILLIAMS: Every decision we make about what property we buy and what property we develop is concerned with water. It has become the number one question that we have. There has to be adequate supply of water. Like the golf courses, we have to get the water in order to have the beautiful grasses.

SCOTT: Williams says it’s simplistic to blame developers for the area’s water shortage, saying they are only responding to consumer demand. But the country club-style developments that characterize much of Atlanta’s growth, others say, use far too much water. Jeff Rader, the president of the Greater Atlanta Home Builders Association, says the industry can help shape demand by educating the public about water conservation.

RADER: They like the luxury of a lot of water. And certainly we have been sort of sold on broad green lawns as a primary manifestation of the good life, particularly in suburban areas. But those are really sort of arbitrary aesthetic preferences and there can be a lot done to move us in the other direction. The key, I think, will be for not only the building industry to assume responsibility for that, but really our entire regional ethic has to change to recognize the scarcity and the value of water.

SCOTT: But even with the growing awareness of the scarcity of water, even with the type of conservation measures that Jeff Rader and others advocate, the water of the Chattahoochee is a finite resource. A recent study projects that the river will be tapped out by the year 2030. By other estimates, the Chattahoochee’s day of reckoning could come much sooner. Communities downstream from Atlanta take their share of water for agriculture and other uses, but by far the biggest strain is put on the river by Atlanta. I asked Bob Kerr of Georgia’s Department of Natural Resources if the city should be allowed to grow unchecked.

KERR: Unless we pass laws to keep people from moving here or we, in some way, curtail the growth through lack of jobs and those kind of things, Atlanta will grow. Now, should we say, all you people that were going to come to Atlanta, how about going down to Columbus and just take the water there? It’s the same water. If it’s not used in Atlanta and it’s used in Columbus, it’s the same water.

SCOTT: If continued growth is inevitable, says Bob Kerr, then ultimately, additional water sources must be explored. There’s talk of building new reservoirs for water storage, or even of piping in water from elsewhere. But some people, like Professor Bruce Ferguson of the University of Georgia, believe some partial solutions may be closer at hand.

FERGUSON: The amount of water that we’re throwing away from impervious services is enormous, and we can reclaim 50 percent of that anyway, very easily.

SCOTT: Ferguson is an expert in the field of storm water management. He believes that better management of rainwater could do much to alleviate water problems in the south and elsewhere in the U.S. He shows me half a dozen samples of porous concrete, which could replace conventional asphalt and concrete on streets and parking lots. The porous pavement would allow rainwater to pass through into the earth where it would slowly work its way into tributaries and rivers. This would not only cut down on floods and erosion, he says, but create a natural and efficient water storage system.

FERGUSON: That water belongs in the soil. That is where it went before we came along and it is a great gift that nature is able to work, if we’ll only let it.

SCOTT: In the meantime, as experts debate the best way to keep Atlanta supplied with water, communities farther down in the watershed, in South Georgia, Alabama and Florida, are staking their own claims to the precious resource. In 1998, the governors of the three states were entrusted by Congress with the task of working out an allocation formula. But more than a dozen deadlines have come and gone since then and the tri-state talks continue to plod on.

[BIRDS CHIRPING]

SCOTT: Back in Helen, Georgia, Dr. Philip Greear predicts those talks with ultimately be fruitless unless decision-makers look beyond regional interests and dare to take a broader view of the issue of water.

GREEAR, P.: Basically, to me there is in our culture and all human cultures the absence of respect for natural systems themselves, and that is particularly true about water. The water cannot be divided between Florida and Alabama and Georgia. I know they’ve been working, the politicians have been working on it for years and they can’t come to any agreement because they can’t answer the question about who owns the water. Because there’s no answer to that question. We don’t own it.

CURWOOD: In a moment, we’ll travel further down the Chattahoochee where the river changes names and character. You’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Kelly Joe Phelps, “I’ve Been Converted” LEAD ME ON (Burnside Record, 1994)]

Related link:

Upper Chattahoochee Riverkeeper

The Rivers South, Part 2

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The story of the Chattahoochee River doesn’t stop in Atlanta. Farther south, the river forms the border between Georgia and Alabama. At Lake Seminole on the Florida line, the Chattahoochee joins together with the Flint River to form the Apalachicola, which flows a hundred miles to the Gulf of Mexico.

The river changes character and supports different ecosystems along its course, from swamps and ravines and flood plains to the unique estuary at Apalachicola Bay.

The river provides a livelihood to people who fish and boat and it’s home to hundreds of species of fish, birds, plants and other animals, some of them found nowhere else. And all who live on the river are affected by decisions made hundreds of miles upstream.

Clay Scott continues his journey down the Chattahoochee and Apalachicola Rivers.

SCOTT: As it flows south along the Alabama-Georgia line, the Chattahoochee River passes through sleepy towns like Cottonton, Gordon and Holy Trinity. This is farmland: fields of cotton, soybeans and peanuts broken up by occasional patches of woods.

But below Lake Seminole, on the Florida-Georgia border, the Chattahoochee becomes the Apalachicola, a river with a markedly different character. Much of the land it flows through is a virtual wilderness, sparsely inhabited forest of pines and hardwoods with impenetrable swamps and ravines. Only a handful of people live in these north Florida woods, and their lives are defined by the river. One of them is Marilyn Blackwell.

BLACKWELL: I piddled in several different things; you know, crawfishing, deadhead logging, catfishing, just, you know, people, a lot of people in this area did things, you know, seasonally, you know, to make a living that is gone now.

SCOTT: The Apalachicola River has always provided Marilyn with at least a modest living, but it’s in the adjacent swamps with their tupelo and cypress trees that she feels most at home.

BLACKWELL: There’s rivers everywhere. But you haven’t got the river swamp everywhere. And it’s just a wonderland. And I spent a lot of time in it and learned a lot of things and it didn’t take long to see the changes going on in what was being done, you know.

SCOTT: Over the years Marilyn saw both the river and the swamps she depended on being degraded and destroyed. One fine day, she tells me, I just woke up angry. She takes me out in a 12-foot boat to show me the source of her anger.

[BOAT MOTOR]

BLACKWELL: That’s another sand deposit. See where the tree line is back in yonder? River used to be way over there. See all these trees here that’s fell in? That’s from where they had the barges tied up and they left them tied up. And you see the force of the water is coming around and hitting that bank and then roll under them barges and cut that bank, undercut it and make the trees fall in. Plus that sand deposit right there, it keeps pushing the river, the water, that way.

SCOTT: The piles of sand she points to are the results of dredging by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, mandated by Congress to keep the river open for commercial barges. The Corps maintains a channel nine feet deep and 100 feet wide, despite the fact that barge traffic in recent years has dwindled to almost nothing. Meanwhile, the silt and sand from the dredging plugs up the sloughs that connect the river to the swamps: vital spawning and breeding ground for countless fish, birds, mammals and other creatures.

BLACKWELL: It’s just like cutting arteries off in a body. The sloughs are where in the summertime during low water, you know, there is a whole, you know, world out there where the otter stayed in low water, you know, they had, you know, water places back in there. And the deer and the raccoon and the birds, there was, you know, the ibis and all had rookeries back there on the sloughs, and all that’s dried up, filled in.

SCOTT: Marilyn Blackwell’s observations are echoed by Jon Blanchard, a biologist from the Nature Conservancy in Florida. Along with the dredging, Blanchard says, the sudden release of water from upstream dams creates a scouring action along the riverbed, further cutting off the river from the swamp and floodplain.

[RUSHING RIVER]

BLANCHARD: And as that river lowers, it disconnects the streams that did feed into it. So, instead of having a connected stream that flows right into the river, what you have is a stream that has a waterfall before it gets to the river. That does at least one really bad thing, which is that it prevents species that live in the river from swimming back up these streams when they need to.

SCOTT: The number of species found here is staggering. The Apalachicola basin has the highest diversity of reptiles and amphibians in the United States and Canada, including the Barbour’s Map Turtle and the Apalachicola Kingsnake. One hundred and thirty species of fish live here, 57 species of mammals, including the threatened Florida Black Bear. Three hundred species of birds, 1,300 plant species. All of them depend, in one way or another, on the intricate balance between the river on the one hand, and the flood plain, swamps and ravines. And that balance is being threatened, both by dredging and by low and irregular flows of water.

BLANCHARD: The real concern that we have here is that we’ll lose the quality and variability of the flows of this river. If we lose the variability flows, that is the floodplain ceases to be flooded at the right time and in the right quantity and for the right duration, many of those fish species will diminish in number dramatically.

SCOTT: The impact of those irregular flows is felt all the way to the Gulf of Mexico, 90 miles downstream. Some ocean species migrate up the river to spawn. Others remain in the bay but depend on the flow of fresh water from the river and the nutrients it brings with it. Not only are the marine species affected but so are the people who depend on them for their living. And that includes almost everyone in Apalachicola, the town known to locals as “Apalach”.

GARRITY: My granddad used to come home with a five-gallon bucket full of bulldozers and shrimp and flounder or whatever, you know, he saved from the catch that day and that was our groceries for the week.

SCOTT: Violet Garrity is the descendent of four generations of fishermen. I met her at the ramshackle marina where she lives in a houseboat with her husband and their three sons, all of them fishermen.

GARRITY: To some people it might have seemed that we had a poor, hard life, but to me, I felt very rich. We had, ate wonderful seafood all the time. Every Friday night we took a bag of oysters out in the back of our yard and had a big fire and put them in it and roasted it.

SCOTT: Violet’s husband and one of her sons are at sea fishing for swordfish. With the dwindling productivity of Apalachicola Bay, fishermen like the Garritys are being forced farther out to sea to find good fishing grounds. Many are quitting altogether.

GARRITY: To me it’s like it’s ending. And I just hate it for the area because it’s so beautiful. And it just makes me sad, it really does. And we’re wondering if maybe it’s not time for us to leave this area too and find another place.

SCOTT: But it might not be easy to find another place like Apalachicola, at least like Apalachicola used to be. Until recently, this remote and beautiful stretch of coast had been miraculously untouched by developers. Now, condominiums and beachfront houses are starting to spring up where fishermen once launched their boats. Still, the biggest threat to this town’s traditional way of life comes from upriver. Woody Miley manages the Apalachicola National Estuarine Reserve. To have a healthy bay, he says, you need a healthy river.

MILEY: A major part of the driving force for productivity in Apalachicola Bay is the leaf litter that falls in the river swamp. This system has evolved dependent on floods, so that that nutrient source is washed from the floodplain and goes through the detrital food web in Apalachicola Bay. We’re not talking just the potential loss of the Apalachicola estuarine system. Collectively and synergistically in these kind of things along the Gulf Coast, we are talking the potential loss of the productivity of the Gulf of Mexico.

SCOTT: Some people in Apalachicola run shrimp boats, others are crabbers or hook-and-line fishermen. But more than anything, this bay has always been known for its famously delicate and delicious oysters. One in ten people here holds an oyster permit and many more work in the shucking houses. And it’s the oysters, says Woody Miley, that are most immediately affected by changes in the river.

MILEY: Apalachicola Bay needs an equitable allocation of fresh water to maintain the salinity gradient in the bay, in particular for the oysters. Because, with the exception of blue crabs, all parasites, predators and diseases of oysters require high salinity. So when the river flows down, there is more of an influence from the open gulf, salinity goes up, parasites, predators and diseases move in and can totally devastate the bars.

SCOTT: Not only are there fewer oysters, people here say, but the lack of fresh water in the bay has begun to affect both their taste and their appearance. The result is a product that is saltier, less distinctive, less appealing and less marketable. For the men and women who harvest oysters in Apalachicola, that has made a hard life even harder.

[SOUND OF DUMPING OYSTERS AND CLACKING OF OYSTER TONGS]

SCOTT; Wade and Diana Marks are one of many husband and wife teams who work the oyster bars together. They balance nonchalantly in an ancient 14-foot wooden boat as pelicans skim the waves nearby. Wade probes the bottom for oysters with a wooden pole, then, working the metal tongs, heaves them into the boat where he and his wife sort through the pile of mud and shells.

MARKS, W.: Well most of the days there’s a lot of shells, there’s a lot to go through to get a few oysters. Used to be like, you know, you could do good.

SCOTT: All this you gotta throw back?

MARKS, W.: Yes. It’s a lot, a lot of work is what it usually is. You just can’t make what you want. [LAUGHS] If you get in ‘em good you can make $60, $70, you know, just according.

SCOTT: $60 or $70 is a good day?

MARKS, W.: Yeah, usually. Yeah.

SCOTT: Is that enough to live on down here?

MARKS, W.: Well, I get by, I’ll put it that way. About all you can do is get by.

SCOTT: It’s hard, and sometimes dangerous, work to harvest these oysters, oysters that end up in the finest restaurants in America. Few oystermen here have savings or insurance. For Wade and Diana Marks, the reward is simply to stay on the water, to avoid, for another season at least, the dreaded alternative: a land job. But both of them acknowledge that day is coming.

MARKS, D.: I like working with my husband. It’s, you just gotta love the water to be on it. A lot better than land. Maybe next year we’ll have a land job, but not this year.

SCOTT: Many residents of Apalachicola blame Atlanta for the changes taking place. It’s the people of that faraway city, they feel, who are sucking their precious river dry with their swimming pools and lawns and fountains. But Atlanta is only a part of the equation, says Lindsay Thomas, who has been working on water issues for years.

THOMAS: This isn’t just about dividing gallons of water. A lot of people will like to think it’s that simple, but behind all of this there is the broader concern about water in the American southeast, as it is a global concern.

SCOTT: Until this fall, Thomas was the federal commissioner, coordinating 11 federal agencies and working with officials of Georgia, Alabama and Florida, trying to find an allocation formula for the waters of the Chattahoochee and Apalachicola Rivers. But a formula alone cannot alleviate the water shortage in the southeast, he says. Only strict conservation measures can.

THOMAS: If you just continue to grow and if you don’t conserve and you don’t manage and you don’t forecast growth and you don’t deal with all of those other issues that have an impact on water and natural resources, you could get in serious trouble. We do not manufacture water. We don’t create one ounce, not one gallon, not one pint, not one quart. The water is there that is provided by nature. That’s all we’ve got. It’s often said here in Georgia, all we’ve got is all we’ve got.

SCOTT: Back on the Apalachicola River, her boat drifting slowly with the current, Marilyn Blackwell couldn’t agree more.

BLACKWELL: When it comes to, you know, people watering their lawns or a river surviving, you know, it’s got to be the river survives, because that’s part of our world. And when you keep chipping away at our world, you’re going to sooner or later, you know, you’re just going to do away with people.

SCOTT: The current water crisis has been a wakeup call to people here in the southeast; a reminder that not even this lush region is immune to shortages, as water becomes an increasingly limited and precious resource all over the world.

For Living on Earth, I’m Clay Scott on the Apalachicola River.

[SOUND OF RIVER FLOWING]

[MUSIC: Kelly Joe Phelps, “Where Do I Go Now?” LEAD ME ON (Burnside Record, 1994)]

CURWOOD: You can learn more about life along the Apalachicola and Chattahoochee Rivers by going to loe.org. You’ll find images by nature photographers Joe and Monica Cook. You’ll hear ecologist Philip Greear talk about his lifelong love of the river. And you can listen to Clay Scott’s personal notebook about his journey. It’s a trip down the Chattahoochee and Apalachicola Rivers on the Living on Earth website, loe.org. That’s loe.org.

And you’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth.

|

An LOE Today Special Feature |

|

|

Philip Greear grew up on the Chattahoochee River. He is nearly blind now, and has lost much of his hearing, but he is still as passionate as ever about the river. Click the image to the left to take an illustrated tour along the river and hear Phillip Greear talk about his lifelong love of this place. (requires Macromedia Flash Player, click here to download if not already installed)

Click here for Clay Scott’s photo album.

News Follow-up[THEME MUSIC] CURWOOD: Time now to follow up on some of the news stories we’ve been tracking lately. Last week, we reported on moves to resume the international trade in ivory. The United States has opposed ivory trading since 1989. But in the latest round of discussions at the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species, the U.S. has reversed its longstanding opposition. It now supports a proposal to let the African nations of Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa make a one-time export of 60 tons of ivory. Theresa Telecky works with the Humane Society of the United States and opposes the sale. TELECKY: When we put legal ivory into international commercial trade it stimulates markets for ivory. This is going to lead to increased elephant poaching and increased illegal ivory trade. CURWOOD: International trade in ivory was banned in 1990 with U.S. support due to illegal poaching that wiped out more than half of Africa’s elephants. [MUSIC BUTTON] CURWOOD: This past May we reported that low levels of the herbicide atrazine caused significant sexual deformities in male frogs in the laboratory. Now, new research has found similar effects on frogs in the wild. Tyrone Hayes is author of the study at the University of California at Berkeley. He says atrazine contamination is widespread in the U.S. HAYES: You go into counties in Nebraska where they don’t use atrazine. It’s still there. You go into Iowa where they do use atrazine but you go into a wildlife refuge where there’s no direct application and you still find it. CURWOOD: Professor Hayes says atrazine could be a factor in the general decline of amphibian populations across the United States. [MUSIC BUTTON] CURWOOD: Even though the United States has refused to join the Kyoto Protocol, individual states are making their own commitments to reduce carbon emissions. So far, nine states have adopted plans to reduce their greenhouse gas contributions. Barry Rabe wrote a report on local climate action for the Pew Center on Global Climate Change. RABE: I don’t think anyone would have hypothesized two, three, four years ago that we would see such robust state activity at a time when the federal government in the U.S. has backed away and some European nations have even begun to back away from some of their Kyoto commitments. CURWOOD: To meet their target commitments, Wisconsin will implement carbon trading, Texas will increase renewable energy and Nebraska will promote farming practices that sequester carbon. [MUSIC BUTTON] CURWOOD: And finally, what would Jesus drive? That’s the slogan for a new evangelical television and radio campaign to encourage Christians to abstain from purchasing SUVs. In an effort to establish moral relationship for climate change, religious leaders preach that Christ himself would rather take the bus than drive a gas-guzzler. And that’s this week’s follow-up on the news from Living on Earth. [THEME MUSIC]

Animal Note/Lizard LoungeCURWOOD: Just ahead, an experiment in local control of federal lands. First, this page from the Animal Notebook with Maggie Villiger. [THEME MUSIC] VILLIGER: Out on the dating scene, some guys have all the luck. In the lizard world, the largest and most attractive males usually take over the best territory by brushing off their smaller competitors. The most desirable turf has lots of rocks for warming up in the sun and shaded nooks and crannies for cooling down. Researchers decided to spice up mating season for a territorial group of lizards in California. They moved the best rocks from the large males’ turf to smaller males’ territory areas, so now the smallest males had the swingingest bachelor pads. And the females responded. The ladies moved to set up housekeeping with the smaller guys.

One clutch of lizards can have multiple fathers, since the mother can mate several times and then later on select whose sperm will actually fertilize her eggs. Having two mates gives the female’s offspring the best of both genetic worlds: larger dads produce the best sons while smaller dads produce the best daughters. So, female lizards don’t waste their time looking for that one perfect guy. Playing the field is an advantage for them and their offspring. That’s this week’s Animal Note. I’m Maggie Villiger. CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth. [MUSIC: Chris Whitely, “Living with the Law” LIVING WITH THE LAW (Columbia, 1991)]

Valles CalderaCURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. In recent weeks, hikers have been paying as much as fifty dollars each to get an up-close look at the Valles Caldera National Preserve. It’s beautiful land at the site of a dormant volcano in northern New Mexico. Two years ago, the U.S. bought this 90,000-acre tract from private owners for about 100 million dollars. And instead of assigning the land to an existing federal agency, Congress broke precedent to set up a largely local, independent board of trustees to run it. The expensive hiking fees and other early decisions by that board have opened a new chapter in the debate over federal lands. Paul Ingles has our story. MARTIN: Now be honest here, now how many people is this the first legal crossing of the fence? INGLES: Craig Martin pushes down on the top of a barbed-wire fence and one by one a dozen hikers carefully step over, including Dave Clark and his wife Caroline Boyle. [WALKING THROUGH GRASS] CLARK: We’ve lived in the area for 15 years and we’ve hiked this area extensively. We’ve just never had an opportunity to cross the fence line into the-- BOYLE: Forbidden territory. CLARK: Yeah, the Valles Caldera area. So, we’re just real excited.  (Photo: Tristan Clum)

MARTIN: The uniqueness of the property stems from its geologic history. INGLES: Craig Martin, the guide for today’s hike, is writing a book on the history of this land. MARTIN: We’ve got a double caldera. A caldera is nothing more than a place where because of a volcanic eruption the surface of the ground drops down, maybe as much as 3,000 feet. And we’re right on the edge of that dropdown area right here. We want to stop here and take a look out towards this beautiful vista here to the southeast. INGLES: A few miles away, the yellowing fall grasses and the vast expanse known as the Valle Grande radiate in the early morning sun. Martin leads us down a steep and rocky incline-- it’s certainly not a finished trail-- that cuts through mixed conifer, aspen and pine trees filling the caldera rim. [ELK BUGLING IN THE DISTANCE] INGLES: Everyone stops short when we hear elk in the distance. Martin says it’s part of an overpopulated herd that was recently thinned out by a short hunting season allowed by the board. A couple of hours later, Martin takes us through the grasslands, past a gathering of other guests invited by the Valles Caldera board---cattle from local ranchers whose grazing allotments on other public lands were limited by the state’s severe drought. MARTIN: I was watching the first shipment come in and the cattle certainly looked like they were stressed from the drought. They were obviously living in a poor rangeland. These guys look pretty fat out here today. They look content. INGLES: The elk hunting and cattle grazing programs were set up by the preserve’s nine-member board of trustees much faster than the U.S. Forest Service, Park Service or Bureau of Land Management could ever have handled them. Those agencies wrestle with, as one park staff reported, tons of regulations and lengthy appeal periods on every decision, constraints that aren’t placed on the Valles Caldera board. Environmental historian William DeBuys is board chairman. DeBUYS: Every national forest is supposed to have a ten-year plan on the book to guide management over the ensuing ten years. And I don’t think there’s anybody in the Forest Service or out of the Forest Service who is familiar with that system who would say that it’s a very good or a very effective system. We want to pursue management adaptively, where we get information on the effects of last year’s work and we use that information to revise how we’re going to approach next year’s work. INGLES: Seven of the board members were appointed by President Bill Clinton. All are New Mexicans, each with an expertise in ranching, forestry, wildlife, conservation or local government. It’s the fact that they are local that concerns John Horning of Forest Guardians, a habitat protection advocacy group that would rather have seen the land run by the Parks Service. HORNING: We think that there is a broader public interest, and the more that lands de-evolve to local interests that the broader public interest in habitat protection and endangered species recovery and clean water and restored streams, those become subservient to the extractive interests. INGLES: Board members point out that all their decisions must still satisfy federal environmental and endangered species guidelines. But Horning considers the grazing program a step in the wrong direction, as rains take the cattle waste into the waterways here which, he says, have long violated water quality standards. The preserve’s executive director Gary Ziehe concedes that fact, but says the act of Congress that transformed what had been called the Baca Ranch into the National Preserve mandates that some ranch activities be maintained. Ziehe considers this first grazing program a cautious step by the board and says the land’s health is rebounding. ZIEHE: Under the previous ownership, grazing was at a level of about 4,000 to 5,000 steers. We’re right now grazing 700 head of cows. And I would emphasize that under the management of the previous owners the condition of the Baca location was improving. INGLES: Another unique goal of this experiment is to make the preserve financially self-sustaining within 15 years. Some environmentalists, like John Horning, worry that mandate might pressure a board to favor money-making extractive uses like logging, mining or more grazing. And with three board terms expiring in January 2003, they wonder how Bush administration appointees might alter policy. Both Ziehe and DeBuys are urging the administration not to make any board changes this time around. Meanwhile, the board’s current priority is getting the public into the property. But the high price of the hikes has drawn objections. ATENCIO: We live in a very poor state, in a very poor region of a poor state. A lot of folks I know would love to get up there but couldn’t possibly afford these hikes. INGLES: Ernie Atencio coordinates the Valles Caldera Coalition, representing 17 local and national organizations, many of which are calling for less expensive public access. But the company hired by the board to run the hikes says, so far, that’s not possible. The preserve gets five dollars from each $50 fee, ten goes to the guide and the rest, says Kimber Barber, owner of Valles Caldera Adventures, pays for shuttle vans, snacks and other business overhead. BARBER: Right now, I’m not breaking even yet, so it’s-- that’s the truth of the matter. So if there’s a way that we can do it for cheaper, we will, and I’d like to see that happen. INGLES: The Coalition’s Ernie Atencio offers some cost-cutting ideas, like staging areas closer to the preserve, using volunteer carpools instead of vans and volunteer guides instead of paid guides. The board says that lower-cost access mostly depends on creating infrastructure first: new parking, drinkable water, improved roads and trails, a visitor’s center, all things the board hopes to put in place without sacrificing the quiet beauty of this remarkable landscape. That’s just one of many challenges facing this unique board that, some say, has been mandated to be all things to all people. For Living on Earth from the Valles Caldera National Preserve, I’m Paul Ingles.

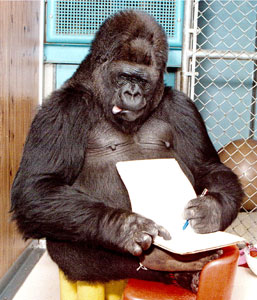

Fine Animal GorillaCURWOOD: Southern California is famous for its reclusive celebrities with finicky tastes, but consider for a moment a star named Koko. Koko lives in northern California at the Gorilla Foundation and she’s the world-famous lowland gorilla who has learned to communicate with humans using American Sign Language.  Koko (Photo: Ron Cohn/koko.org/The Gorilla Foundation)

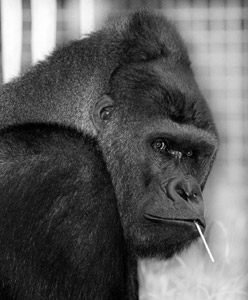

HAYNES: We asked them to send us any materials they had relating to Koko and the other gorillas at the foundation. And because she understands English and she communicates through a variant of American Sign Language, they talk to her every day and she has opinions about everything and they write down transcripts of these conversations. And we read the transcripts and we took certain phrases, for example, “Fine Animal Gorilla,” the name of the album, is Koko’s name for herself. And we took it from there. And all the lyrics on the album are taken from this material. It’s very specific to Koko. And when we play these songs for her, she recognizes this. MUSIC: Koko, “Fine Animal Gorilla” FINE ANIMAL GORILLA (Laurel Canyon Animal Company, 2002): CURWOOD: There’s a bit of an African beat to this, I gotta say. HAYNES: Yeah, it’s sort of a rap sort of beat. Although we stayed away from a lot of African stuff with Koko because she’s not African. She was born in San Francisco on the Fourth of July. CURWOOD: That makes her as American a gorilla as you can be, huh? HAYNES: You bet. CURWOOD: Koko is credited as being a producer on this CD. What was her creative input? HAYNES: Well, credited as being a producer, in one sense she actually is, because, for example, on “Fine Animal Gorilla” it was played for her, and there’s a line in it that I believe is a rhythmical answer. It wasn’t really lyrical content but it was a, “Do you think I’d lie?” And it was just an answering phrase. And when she heard it, she sang the word “shame,” so we took it out. CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] She scolded you, huh? HAYNES: Well, I wasn’t scolded, she just didn’t want to be represented as lying, you know, so she didn’t like that. CURWOOD: Tell me how this works exactly. Does Koko have someone sign the lyrics to her? HAYNES: She listens to the song. CURWOOD: Yeah? HAYNES: Oh yeah. CURWOOD: And she understands the story, huh? HAYNES: Absolutely. Totally sentient being. But she liked this song because her name is in it a lot. “Scary Alligator,” the second song, Koko has a scary alligator, it’s a plastic alligator, a toy alligator, and she kind of scares people with it and she calls it her scary alligator. And she liked the second version of that better because there was more stuff in it. MUSIC: Koko, “Scary Alligator” FINE ANIMAL GORILLA (Laurel Canyon Animal Company, 2002): CURWOOD: So “Scary Alligator,” how did Koko react to this song? HAYNES: Well apparently she liked it a lot because the Foundation told us she picked up her scary alligator and plunked out a melody on her keyboard. It inspired her, I hope. I hope that’s what it meant. But we’re trying to get that. Now we’re trying to get the melody she wrote from the Foundation. I don’t know if they recorded it or not. Because if we can, we’re going to try to write a song around it. So Koko actually contributed a melody. It would be great. I mean, because our original intent was at some point to actually see if she’d like to play in a band. CURWOOD: There’s a sad song on here called “Even Gorillas Get the Blues”. I understand this is about Koko’s companion, Michael, who died. Let’s take a listen to that now. MUSIC: Koko, “Even Gorillas Get the Blues” FINE ANIMAL GORILLA (Laurel Canyon Animal Company, 2002):  Michael (Photo: Ron Cohn/koko.org/The Gorilla Foundation)

And Michael also had about 500 words in American Sign Language-- not quite as much as Koko. But when they asked him what was wrong he told them-- because Michael came from the Cameroons. He was captured in the Cameroons when he was about three years old. And he told them he was having a nightmare about poachers killing his parents and capturing him, and I just, it just floored me. And when we heard that, we realized if you can tell people things like this, it makes them look at the animal in an entirely different light and hopefully, you know, look at human beings in an entirely different light, also. CURWOOD: What did your performers think of this Koko project? I mean, singing about a gorilla in a gorilla’s own words can’t exactly be a typical gig. HAYNES: Well, you know, one of the great things about what we’re doing here is that normally when you’re doing a record, everybody, record companies and everyone, are concerned with if you have a sound that you maintain that sound and don’t spread out, and this just allows us to do whatever we want and it’s really fun. I mean, there were literally almost 40 people involved in creating this album. Because one of the things that happened was Kelly Sullivan, who just sang “Fine Animal Gorilla,” her mother, Julie, teaches at a middle school, at Nimitz Middle School in Huntington Park, California. And she took the Koko album, the idea of Koko, to her class and her class just totally embraced it to the point where they made books for Koko and they went online and they attained a global awareness in about a week of all the horrible things that are happening in Africa about the gorillas and so forth. And they got so into it, we asked the kids if they would write a song for the album, and they did. They wrote “Koko and the Nimitz Kids”. And then we asked them if they would like to sing the song, and 21 kids showed up.  The Kids from Nimitz Middle School (Photo: Ron Cohn/koko.org/The Gorilla Foundation)

CURWOOD: A little Latin rhythm here in this song. HAYNES: Yeah, because most of the kids are Latino. So that’s another thing, we got to write bilingual, trilingual stuff now, I guess, if you count Koko. [LAUGHS] CURWOOD: Skip Haynes is one of the founders and the producer at the Laurel Canyon Animal Company, which just released the CD “Fine Animal Gorilla”. Thanks so much for taking this time with me today. HAYNES: Thank you very much. CURWOOD: And give our thanks to Koko, as well. HAYNES: I certainly will. Related links:

CURWOOD: And for this week, that’s Living on Earth. Next week, scientists say you may have been looking in the wrong places to see if chemicals cause certain cancers. New evidence suggests that early exposure to dioxin, for example, may lead to breast cancer much later in life. FEMALE: We’re raising the question, maybe the critical time of exposure was in the womb or during infancy or during puberty, long before the tumors ever develop. CURWOOD: New clues in the breast cancer mystery, next week on Living on Earth. [MUSIC: Earth Ear/David Dunn “Chaos and the Emergent Mind of the Pond” (Earth Ear, 2002)] CURWOOD: We leave you this week with “Chaos and the Emergent Mind of the Pond”. That’s the appropriate title David Dunn gave this mix of recordings of underwater insects who inhabit small ponds from Africa to New Mexico. [SOUND OF INSECTS IN WATER] CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at www.loe.org. Our staff includes Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Cynthia Graber and Jennifer Chu, along with Al Avery, Susan Shepherd, Jessica Penney and Carly Ferguson. Special thanks to Ernie Silver. We had help this week from James Curwood, Andrew Strickler and Nicole Giese. Allison Dean composed our themes. Environmental Sound Art courtesy of EarthEar. Our Technical Director is Chris Engles. Ingrid Lobet heads our western bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor. And Chris Ballman is the senior producer of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood, executive producer. Thanks for listening. ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include: the National Science Foundation, supporting environmental education, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living on Earth’s expanded internet service, the Ford Foundation for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues, the W. Alton Jones Foundation, supporting efforts to sustain human well-being through biological diversity, and the Oak Foundation, supporting coverage of marine issues. ANNOUNCER 2: This is NPR, National Public Radio. This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!Living on Earth Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth! NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

|