December 6, 2002

Air Date: December 6, 2002

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Israeli Water Crisis

/ Sarah ZabeidaView the page for this story

In Israel, political unrest and violence too often dominate the headlines. But there’s a looming crisis in that nation we don’t hear much about. As Sarah Zabeida reports, Israel’s water supply is threatened by drought and government mismanagement. (10:40)

Health Note/Mercury & Vaccines

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on a new study that shows children immunized with vaccines containing a mercury-based preservative end up with an insignificant and short-lived blood mercury level. (01:15)

Almanac/London Smog

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about London’s Great Smog. The worst “pea souper” in modern times occurred fifty years ago. (01:30)

Plundering Paradise

View the page for this story

The Galapagos Islands have been considered precious ecological gems by biologists and environmentalists ever since Charles Darwin made his historic landing more than 170 years ago. But author Michael D’Orso didn’t go to the islands for the wildlife. In his new book, “Plundering Paradise: The Hand of Man on the Galapagos Islands,” D’Orso explores the rich history of people and profit on the islands. (09:00)

Gap in Nature

View the page for this story

In the latest installment in this occasional series, we’ll hear how a single pet cat eradicated a species of bird. (03:00)

Unlikely Eco-campaigns

/ Bruce BarcottView the page for this story

Reviewer Bruce Barcott takes a look at some eco-friendly commercial crusades from two unlikely sources: Shell Oil Company and the Evangelical Environmental Network. (03:00)

Tech Note/Sticky Solution

/ Cynthia GraberView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Cynthia Graber reports on a new technique to deal with adhesives that clog up paper recycling. (01:20)

Auto-immune Disease Clusters

/ Rachel GotbaumView the page for this story

Two Boston neighborhoods are the focus of an unprecedented public health study. In these areas, the rates of scleroderma and lupus, both autoimmune diseases, are many times higher than normal. As Rachel Gotbaum reports, Massachusetts is investigating whether pollutants might be the cause. (08:45)

Regreening the Medina

/ Clark BoydView the page for this story

The medina, the old town of Marrakech, Morocco, was once known as “the garden city of North Africa.” Private homes had lush courtyards; orchards, grapevines and trees filled the city streets. But as the population grew, the gardens made way for shops and houses. But there’s a new movement to bring back the gardens of the medina. Clark Boyd reports. (06:15)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Laura KnoyREPORTERS: Sarah Zebaida, Rachel Gotbaum, Clark BoydCOMMENTATOR: Bruce BarcottGUESTS: Michael D’Orso, Tim FlanneryUPDATES: Diane Toomey, Cynthia Graber

[THEME MUSIC]

KNOY: From NPR, this is Living on Earth. I'm Laura Knoy. Most of us think of the world-renowned Galapagos Islands as Charles Darwin's Eden of evolution. But one author says the island's human inhabitants are just as interesting as its famed flora and fauna.

D’ORSO: Many of them are actually unaware and really could not care less about the Galapagos that we see on the Discovery Channel and National Geographic, the place that so entrances biologists and environmentalists.

KNOY: It's the other Galapagos, this week on Living on Earth. Also, the race is on to find out what's causing auto-immune disease among women in Boston and whether industrial chemicals are to blame.

LOMBARD: I never really felt a sense of urgency, but after the three deaths in 2001, I feel that sense of urgency; urgency to get some answers, before the rest of us are dead.

KNOY: Unraveling the cluster mystery, right after this.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

Israeli Water Crisis

[THEME MUSIC]

KNOY: Welcome to Living on Earth. I'm Laura Knoy sitting in for Steve Curwood.

Anyone listening to today's news from the Middle East would likely list religion and land as the main causes behind current conflicts. But there are some who say that in a few years it will be water that the region's inhabitants will be fighting over. Water is vital to any potential solution in the Middle East. For example, the existing peace treaty between Jordan and Israel eight years ago was built on condition that Israel supply water to its neighbors from scarce, but, nonetheless, shared supplies. But after five years of drought, the water situation in Israel is deteriorating rapidly. Experts say drinking water could run out this decade if immediate rationing measures aren't taken. A state of emergency was declared recently, after a governmental inquiry found that a shortage of rain wasn't the only problem. Sarah Zebaida has our report.

[WATER LAPPING ONTO SHORE]

ZEBAIDA: This is the freshwater lake where Christians believe Jesus walked on water, right here on the Sea of Galilee, known as the Kinneret by locals. It was also Israel's most important and faithful source of water until this year, supplying water for Israelis, Palestinians and Jordanians.

But there is trouble here. Today, the Sea of Galilee is almost 700 feet below sea level. That's well below the so-called “emergency red line,” the point that signals serious damage to this country's giant natural reservoir. The once sweet, fresh water is slowly turning salty as the sea literally shrinks. Healthy plankton and fish that naturally clean the lake are slowly being replaced with harmful blue algae.

Here at Kibbutz En Gev on the eastern shore of the Sea of Galilee, the water's edge is rapidly receding into the distance. Sophia is a waitress at a famous fish restaurant on the kibbutz.

[SOUND OF PEOPLE IN RESTAURANT]

SOPHIA: When I was little, we used to go ever summer to the Kinneret and on this exact place where I'm standing the shore just ran away. It was just beside me, and now I have to walk like two minutes, three minutes, in order to get into the water.

ZEBAIDA: People have been fishing in this region for millennia. Menachem Lev carries on that tradition. Every morning for the past 22 years, he's been fishing on the Sea of Galilee. Now, for the first time, he can see the bottom of the pier that juts out into the water.

[SOUND OF WATER LAPPING SHORE]

LEV: We didn't used to see the lake like this, and we feel very sad, like me. Once I see the harbor full and everything, but we carry on. We have to believe in God that he should bring us rain.

ZEBAIDA: Indeed, a common sight these days in the region is planeloads of orthodox rabbis flying over the sea reciting special prayers for rainfall. But it's not only the Sea of Galilee that's become depleted. For instance, the coastal aquifer under the city of Tel Aviv has been overdrawn and as a consequence, salt water is intruding from the Mediterranean Sea.

The Jewish National Fund, which receives the majority of its financial support from the Jewish community in America, has helped build hundreds of reservoirs under Israeli control. But the JNF's president, Ronald Lauder, feels that many Israelis are underestimating how grave the situation is.

LAUDER: When I travel throughout the United States when they do have a drought, I notice that in every bathroom there is a sign talking about saving water. There are fountains that are turned off. But at the same time, we have a much more acute water shortage in places in Israel. And to have people continue to wash their car and water the lawn, I believe, is nothing short of criminal.

ZEBAIDA: There are penalties on the books for wasting water. For example, the fine for watering lawns during the summer is close to $2,000, but enforcement is difficult. A new environmental police force was launched shortly before the latest violence broke out, but in the past two years, those green police have scarcely been seen. And despite the fact that Israel sits in the middle of an arid region, in many ways it has a western lifestyle, complete with western levels of water consumption. Gideon Witkin is the Director of Israel's Lands Authority, an agency that controls all state-owned land.

WITKIN: We see an increase of level of living and more house and gardens, more grass, more public gardening, beautification of the country and everything. This consumes a lot of water, and to cut down on that, it is really very, very, very difficult, because you are cutting down on quality of life.

ZEBAIDA: Conserving water is something the government tries to ingrain into Israeli consciousness from childhood. There are even public service announcements on radio and television urging Israelis not to waste a drop. In this one, a child scolds his mother for leaving the tap water on while brushing her teeth.

[YOUNG CHILD AND MAN SPEAKING HEBREW]

ZEBAIDA: Despite bombs and borders dominating the news, the water crisis managed to make the headlines recently. The government has just declared a two-year water emergency. That announcement came as part of a parliamentary inquiry into the water crisis. In the recently released report, officials reserved their harshest criticism not for the drought, but for endless bureaucracy that has delayed the construction of wastewater purification and desalination plants. But it seems that the Israeli public has some criticism of their own. They blame the water crisis on agriculture. Israel's legendary Jaffa oranges and Galia melons have been sold across Europe and America for more than 40 years. But these farmers buy their water at prices heavily subsidized by the government. So is too much of the nation's water supply being shipped out of the country in the form of fruit for too little gain? Philip Warburg is the director of Israel's Union of Environmental Defense.

WARBURG: The farm sector receives in excess of 50 percent of the water supply for he nation, and yet provides roughly, I think, two percent of the nation's GNP. So you're talking about allocation of a scarce resource to a not very productive sector, in a very inefficient manner.

ZEBAIDA: Under the crisis declaration, Israel will drastically increase the price of water for farmers, and expedite the plans for wastewater purification and desalination plants.

The Arab/Israeli conflict pervades every aspect of life in the Middle East, and water is no exception. The Israeli government controls the amount of water sent to the Palestinians living in the West Bank in Gaza, but those populations complain that their supplies are woefully inadequate. Indeed, the average Israeli uses four times as much water as the average Palestinian in the West Bank in Gaza.

Efrat Gamliel from Friends of the Earth Middle East heads a project called Good Water Neighbors which aims to foster cooperation between Israeli, Palestinian and Jordanian communities on water issues. She thinks Israel has yet to confront the issue of water equity.

GAMLIEL: For one year they studied the water crisis in Israel, and they issued a very detailed, long report. They only dealt with the water in Israel, like we're isolated on an island or something. They never mentioned that we have mutual water resources and that the Palestinians are part of them, and we must look at the picture like that. I think it's a big mistake to look at Israel as a separate unit. It's not.

ZEBAIDA: The battle for depleted water resources becomes even more fierce when the water quality itself is compromised. The many rivers that flow throughout Israel and the West Bank cannot be used as a water resource because of dangerously high levels of chemical waste and bacteria, such as E. coli. Many of these rivers originate in the Palestinian-controlled cities in the West Bank, where there is little infrastructure to treat wastewater. The strained and limited cooperation between the Palestinian authority and Israeli environment officials, coupled with the growing amounts of Palestinian industrial waste, muddies the waters even further.

Philip Warburg says that both Israel and the Palestinian authority have neglected water protection for too long, and neither side can afford to wait for peace before dealing with the crisis.

WARBURG: There is a tendency in the Middle East where security issues loom very large to regard environmental protection as a luxury that should be dealt with once the other problems are solved. And I think that the water issue is a very good issue to demonstrate that environmental protection can't wait.

ZEBAIDA: The search for solutions to the water crisis have led to an unorthodox proposal: to mine for water in the desert.

LAUDER: One of the areas that I believe there is great potential for is the Negev, which is the major desert in the center of Israel. There is the distinct possibility, almost a certainty, that there is fossilized water underneath the Negev.

ZEBAIDA: The Israeli public may be wary of using fossilized water, but Ron Lauder is undeterred. The Jewish National Fund has already spent millions of dollars to develop the special mining equipment to extract the estimated billions of cubic meters of water from nearly a mile underground.

LAUDER: Interestingly enough, water does not age. Although you have to clean up the water a little bit, it is really water, and this is part of the future.

ZEBAIDA: Critics say the project's huge costs cannot be justified since this is a non-renewable, once-only water source. But if this project proves successful, the Jewish National Fund plans to donate the technology to Syria and Jordan so they, too, can mine for their own fossilized water.

[SOUND OF CROWD OF PEOPLE NEAR WATER]

ZEBAIDA: The waste water and desalination plants are expected to be up and running by the end of next year. If successful, the Negev plan is also at least two years from reality. Meanwhile, vacationers here on the Sea of Galilee are getting used to dragging their beach chairs a few more feet each year to get to the water's edge. For Living on Earth, I'm Sarah Zebaida at En Gev Beach on the Sea of Galilee.

[SOUND OF CROWD OF PEOPLE NEAR WATER]

[MUSIC: Thomas Dolby, “The Flat Earth” THE FLAT EARTH (Capitol, 1994)]

Health Note/Mercury & Vaccines

KNOY: Just ahead, how human activity on the Galapagos could leave the islands a paradise plundered. First, this Environmental Health Note from Diane Toomey.

[THEME MUSIC]

TOOMEY: In recent years there has been growing concern that disorders such as autism may be linked to the cumulative effect of childhood vaccinations. That's because many vaccines use a mercury-based preservative known as thimerosal, and mercury is a known neurotoxin. Now, for the first time, researchers have completed a detailed analysis of blood mercury levels in infants immunized with vaccines containing thimerosal. In this small study, University of Rochester researchers took blood samples from about three dozen infants about a week to three weeks after vaccination. Researchers found that most children had blood mercury levels of one or two nanograms per milliliter. That's well below the EPA's safety limit of 5.8 nanograms, a threshold regulators believe that itself is a small fraction of the mercury concentration that would actually cause harm. In this study, the highest level of mercury found in an infant was 4.1 nanograms, still below the EPA limit.

Researchers also say it appears that mercury is excreted from infant's bodies much quicker than previously thought. Thimerosal has recently been phased out of U.S. vaccines, but it is still widely used in vaccines administered overseas. And that's this week's Environmental Health Note. I'm Diane Toomey.

KNOY: And you're listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Thomas Dolby, “The Flat Earth” THE FLAT EARTH (Capitol, 1994)]

Related links:

- University of Rochester press release

- Published in The Lancet, latest issue, Nov. 30

Almanac/London Smog

KNOY: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I'm Laura Knoy.

[MUSIC: Yehudi Menuhin & Stephane Grapelli, “Foggy Day in London Town” YEHUDI MENUHIN & STEPHANE GRAPELLI PLAY GERSHWIN (EMI, 1988)]

KNOY: England's climate has never been anything to crow about. But 50 years ago this week, the weather in London turned downright fatal. The city has always been known for its thick fogs, and the Industrial Revolution added air pollution to the mix, creating smog. The worst pea soup in modern times took place in 1952. November that year was nine degrees colder than average, and to keep warm, Londoners resorted to burning more coal than usual. The fires produced a thick smoke heavy with sulfur dioxide.

In early December, a high-pressure system settled over London and trapped the noxious fumes beneath low-lying clouds. The water vapor reacted with the smoke, turning the fog brown and creating toxic sulfuric acid. The air was so acidic that it burned skin, eyes, lungs and even iron work. With no wind, the city choked for five straight days. Visibility dropped to a few feet and emergency workers had to guide ambulances with flares. Health officials blamed the putrid air for thousands of deaths due to bronchitis, pneumonia, and heart attacks.

Thanks to the great smog of 1952, Parliament passed several acts that reduced domestic coal use and mandated taller chimneys on factories. The laws worked. But instead of choking on coal smoke, Londoners now gag on auto exhaust. Last year, London had only one air quality warning for sulfur dioxide, but 14 bad air days due to ozone pollution. For this week, that's the Living on Earth Almanac.

[MUSIC ENDS]

Plundering Paradise

KNOY: The Galapagos Islands have been described as a shower of stones scattered across the equator, just off the coast of Ecuador. And since Charles Darwin's historic landing there nearly 170 years ago, these scattered stones have been considered precious ecological gems.

But it wasn't the rare species of flora and fauna that drew author Michael D'Orso to the Galapagos; it was the people. His new book is called “Plundering Paradise: The Hand of Man on the Galapagos Islands”. It chronicles the history of this famous archipelago from its early Norwegian settlers, to the people who today make their living from a burgeoning eco-tourist industry. Michael, hi. Welcome.

D'ORSO: Thanks, nice to be here.

KNOY: Who lives on the Galapagos Islands?

D'ORSO: Well, I had no idea anyone lived there other than park rangers and maybe a few tour guides, until a friend came back from vacation there five years ago and made a reference to staying at the Hotel Galapagos. And my ears perked up at that point. I said, "There is a hotel in the Galapagos?" and came to find out, with a little bit of research, that there are close to 20,000 people who live in the Galapagos today. That 20,000 people-- about half of them are Ecuadorians and Ecuador is the nation that owns the Galapagos-- and that half of that 20,000 are Ecuadorians who have arrived there in the last ten years.

KNOY: What brought the Ecuadorians there?

D'ORSO: Well, the Galapagos has always been a tourist destination, but until ten years ago, the three percent of the Galapagos which are inhabited was still a pretty rough place to live. There was no fresh water to speak of. There was no electricity. But about ten years ago, there was a desalinization plant put in outside of the largest of the four villages. Electricity arrived and with that, many desperately poor Ecuadorians in the mainland, smelling the tourist dollar, headed out to the largest of the four villages, Puerto Ayora, looking for work. So, a large number of those people who came out to the Galapagos, many of them are actually unaware and really could not care less about the Galapagos that we see on the Discovery Channel and National Geographic, the place that so entrances biologists and environmentalists.

KNOY: Now, you said that about half of the people that live there now are from Ecuador. Where are the other half from?

D'ORSO: Well, the other half are the people that have--just an amazing mishmash of people who have settled in the Galapagos over the past century. And you're basically talking about a lot of expatriates from all over the world for one reason or another, people who have left the place where they lived to literally go to a desert island, to go to the end of the world. And understand, people have known about the Galapagos far back before Darwin's arrival in 1835, but they never stayed because it's a pretty harsh place. We're talking about volcanic islands right on the equator out in the Pacific.

The first permanent residents were Norwegians who came in the 1920's to escape the hardship in their own land, sailed there, and actually put down roots and stayed. And to this day, you still have some of the descendents of these Norwegians with names such as Hendrickson, and Lunt. Then you had Germans arriving in the 1930's, fleeing the rise of Hitler's Germany. So you have names like Engermeyer and Vitmer. Then you have just a whole variety of dreamers, utopians, con men, hustlers; people who want to get away for one reason or another, from the regular world.

KNOY: Let's talk about some of the other characters in your book. How about Jack Nelson, the hotel owner? He's got some very interesting and quite conflicted views about tourists.

D'ORSO: Jack is a pretty compelling figure. He's one of the older established residents on the island. Jack, in the late 1960's, got his draft notice to go to Vietnam and wasn't about to go there, and didn't want to go to Canada--it was a bit too cold for his tastes. But he had an errant father who had left the family in Southern California back in the 50's when there was virtually nothing there. In fact, his father set up a camp on a point of land where the Hotel Galapagos now sits. But in that time, the father had a couple of cots and a tent, and he'd make some food and give scientists and travelers a place to sleep for a couple of bucks. Pretty soon, he built one shelter, then another, and it grew into a pretty rustic hotel.

Well, when Jack got his draft notice, he had his dad down in the Galapagos, that's where he went. And today, Jack Nelson is the U.S. Consulate Representative for the Galapagos Islands, and is very, very involved in the development, and the responsible development of the tourism industry in the islands. He runs the hotel, and he's quite an activist; even helping to guide the writers of a lot of the legislation that protects the islands today. Of course when you say--

KNOY: Well how does he feel about the tourists? Because you know, clearly they have an impact on the island.

D'ORSO: Well that's, right, yes.

KNOY: And he's concerned about that, and yet he's also helping to bring them in because he runs a hotel.

D'ORSO: Well, his feelings, essentially, are in terms of the tourism itself, fatalistic. I mean, he makes the point that people are going to come. You can't keep people away. They're coming to Antarctica, every corner of the planet, people are going to come. If they're going to come, he says let's try to construct an edifice that allows them to come and have as little negative effect as possible.

What he's more concerned about, and what most of the people down there are most concerned about, is the threat to the islands, not from the tourism industry itself—although, occasionally, you'll have your derelict oil freighter for example, such as the one that broke apart and you had the pretty massive spill there in January of 2001. But those kinds of accidents aside, the real threat to the islands comes from both the onshore ancillary development that comes with the actual tourism out there among the boats.

You know, you are talking about waterfront. Darwin Avenue is lined with restaurants, discothèques, pool halls; it's a pretty developed place, and you've got problems with that kind of development outstripping the infrastructure, because the sewage system, electricity, and sanitation are all trying to keep up with the demands of all of those people.

KNOY: Let's talk about another character in your book who has very definite views about the tourists. He's Furio Valbonese. Who is Furio?

D'ORSO: Well Furio is the owner of the large resort hotel being built up on the slopes of the volcano above the town of Puerto Ayora. Furio has been living in the Galapagos quite a long time, and he's very unabashed about the fact that he tried to make a go of it the traditional way down in town. He ran a couple of tour boats that he said both tended to sink. He's tried his hand at a lot of businesses down in town and then opened up a restaurant up in the highlands that was pretty successful. And he now, with the backing of an international consortium of resort hotels, has opened a hotel in the highlands called the Royal Palm. And he's looking for very, very high-end guests. He's looking for the kind of people that actually can come in on their own cruise ship and can actually helicopter up with either their own aircraft, or he plans to have one or two of his own to go down and ferry them up to this quite lush place. We're talking about thatch roofed, luxury suites, if you will. They're almost individual homes up there, with whirlpools, Jacuzzis, observatory. They're looking to build a golf course, which will be very interesting to watch, because we're talking about jungle up there. It will be pretty hard to keep that jungle back. In any event, there is a lot of--

KNOY: A golf course? Are they going to let them do that?

D'ORSO: So far, yes. I mean, the place is already open for business. This is the Galapagos Islands we're talking about, and it's kind of controversial down there. A lot of people are debating is this what the Galapagos is supposed to be, and what does this bode for the future?

KNOY: How do you think most Galapagosians feel about tourists?

D'ORSO: Yeah. Well, the old timers, they basically have the same view as Jack Nelson: controlled tourism that respects the essence of what the Galapagos is. They are absolutely in favor of that. The newer arrivals, the second wave of Ecuadorians coming out and looking for work basically, their view is a view that is shared by many people in the Ecuadorian government. And again, there are good guys in the Ecuadorian government who are all for protecting the nature of the islands. There are others that want to throw open the waters to fishing, throw open the islands to development, build resort hotels on the sides of all of those volcanic cliffs, and make it like the Caribbean.

KNOY: Michael, the title of the book is “Plundering Paradise: The Hand of Man on the Galapagos Islands’. The word "paradise" is often used to describe the Galapagos. How much of this paradise do you think is left?

D'ORSO: When you get outside of the four communities on four of these islands where the people live, and you get out into that other 97 percent of these islands, the islands are no different from the place that Darwin stepped ashore in 1835, and you feel like you're just at the beginning of the planet. And it's easy to see why it's such a Mecca, such a trip of a lifetime, for so many people.

KNOY: Michael D'Orso is author of “Plundering Paradise: The Hand of Man on the Galapagos Islands”. Michael, thank you.

D'ORSO: Thank you.

Gap in Nature

KNOY: The most famous animal inhabitant of the Galapagos Islands is, of course, the tortoise. In fact, the name "Galapagos" is taken from the Spanish word for a kind of saddle that the tortoise's shells resemble, and Charles Darwin used the giant reptiles to help explain his theory of evolution.

Originally, there were 15 different species of Galapagos tortoise. Four of these are now extinct, and the rest are endangered. In our continuing series we call "A Gap in Nature," author Tim Flannery profiles another species we'll never see again.

[MUSIC: Roger Eno, “Aryis” SWIMMING (All Saints Records, 1996)]

FLANNERY: Very few species have been exterminated by a single individual, but such was the fate of the tiny Steven's Island Wren. The only known perching bird incapable of flight, the Steven's Island Wren was a subtly spotted bird once common throughout the New Zealand area. But before the arrival of Europeans, a rat brought by the Maori eliminated it from over 99 percent of its habitat.

(Illustration by Peter Schouten)

Its last refuge was the small rocky outcrop of Steven's Island. In 1894, the New Zealand government built a lighthouse there and the lonely lighthouse keeper decided that he must have a cat for company. Within a year or so, that solitary feline had caught every one of the island's tiny wrens. Tibbles then brought them one by one and very much dead, to David Lyle's door. Thinking them strange birds, Lyle sent 17 little bodies to a museum for identification. So this is the case of a species discovery and extinction all in one fell swoop.

Lyle was the only European ever to see the birds alive, and even he observed them just twice. He reported that they ran about like mice among the rocks. Twelve of Lyle's, or should we say, Tibble’s specimens, are still held in museum collections today.

KNOY: Tim Flannery is author of “A Gap in Nature: Discovering the World's Extinct Animals”. To see a picture of the Steven's Island Wren and other ex-animals go to our website loe.org. That's loe.org.

And coming soon to the Living on Earth website, award winning children's book author Lynne Cherry reads from her new release “How Groundhog's Garden Grew”. It's a story about how one little critter learns to grow his own food instead of stealing his neighbor's, and Cherry says there is a lesson for all kids.

CHERRY: There is really no problem getting out in nature even if you live in the city. You can take a magnifying glass and you can look at the plants growing in the crack of a sidewalk. In fact, E.O. Wilson got his start as a biologist as a child looking at ants coming out of the cracks in the sidewalk. So nature isn't something that's only out in the country, nature is everywhere.

KNOY: For illustrations and readings from Lynne Cherry's “How Groundhog's Garden Grew” and other works, visit the Living on Earth website, loe.org starting Monday, December 9th, that's loe.org.

You're listening to NPR's Living on Earth.

Related link:

“A Gap in Nature: Discovering the World’s Extinct Animals” by Tim Flannery

Unlikely Eco-campaigns

KNOY: The oil giant Royal Dutch Shell and a group called the Evangelical Environmental Network have something in common. They have recently started airing their own eco-friendly commercials. Both groups are trying to persuade the masses to go green. Bruce Barcott takes a look at these unlikely ad campaigns.

BARCOTT: I don't know much about oil, but I do know that I want to go camping with Damien Miller. Damien stars in a new TV ad designed to put an eco-friendly face on Shell, the world's third largest oil company. In the ad, we see Damien greet the sunrise on a remote desert highland and warm his coffee over a campfire. He's got a scruffy beard and flyaway hair. Damien defines earthy-crunchy.

[MUSIC]

MALE VOICE-OVER: He believes that almost half our energy could one day come from renewable sources like solar panels and sustainable forests. He's been called a dreamer, an oddball.

MILLER: I’ve been called a hippie.

MALE VOICE-OVER: And more recently, a project manager for Shell.

BARCOTT: You heard it. Over at Shell they're hiring hippies. Damien's 30 second spot is one of a flurry of new ads that have turned the space between TV shows into an environmental battleground. Shell's actually playing catch-up to BP, the world's second biggest oil company, which began pitching itself as your solar-friendly oil giant back in the late 90s.

As a conscientious gas junkie, these ads leave me torn. A new book by environmental analyst Jack Doyle, called “Riding the Dragon: Royal Dutch Shell and the Fossil Fire” chronicles the company's dismal history of environmental abuse.

But Shell is taking baby steps to improve its record. It's investing one billion dollars over the next five years in renewable energy projects, for instance. That's less than half the profit Shell made in the last three months alone. Still, it's a start.

For its part, BP has been lobbying to open up the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, and I don't think they mean for solar panels. Except just recently BP abandoned its ANWR effort as not worth the PR price. So, is it now worthy of my $20 fill-up?

Thankfully, there is a third ad campaign that clarifies the issue: The Evangelical Environmental Network, a coalition of holy-rollin’ tree huggers, recently unveiled a TV spot that puts our fossil fuel consumption in a religious context.

[MUSIC]

MALE VOICE-OVER: Too many of the cars, trucks, and SUV's that are made, that we choose to drive, are polluting our air, increasing global warming, changing the weather, and endangering our health, especially the health of our children. So if we love our neighbor, and we cherish God's creation, maybe we should ask, "What would Jesus drive?"

BARCOTT: What would Jesus drive? What I want to know is where would he gas up?

KNOY: Commentator Bruce Barcott writes about the environment for Outside Magazine.

[MUSIC: KB Jonstad, “Walken In” (ECM, 2000)]

Tech Note/Sticky Solution

KNOY: Just ahead, a new approach to explaining disease clusters. First, this Environmental Technology Note from Cynthia Graber.

[THEME MUSIC]

GRABER: The adhesives that binds magazine pages together and makes those address labels stick to envelopes can cause huge problems at the recycling plant. When the sticky stuff goes through the disassembling system, it can clog the screens used to clean the paper. And if any of the goop gets on newly pressed paper during the drying process, it can pull and rip the sheets.

Right now, the only way to get rid of the clumps of adhesive is to wash them away with chemical solvents that recyclers say are difficult to work with and can pollute the environment.

Now, a scientist from Buckman Laboratories in Tennessee says he has a solution. He's uncovered a biological enzyme that breaks down large sticky globules into smaller ones. This way, adhesives wash out of the system in the cleaning stage and don't gum up the works. Eventually, the enzyme breaks down and leaves no environmental pollution.

Right now, this enzyme costs a lot more to use than chemicals. The paper companies that have tested the enzyme say it has led to a significant increase in production, and scientists say they can easily grow the enzymes on an industrial scale. That's this week's Technology Note. I'm Cynthia Graber.

KNOY: And you're listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Thelonious Monk, “Sweet and Lovely” SOLO (CBS, 1958)]

Auto-immune Disease Clusters

KNOY: It's Living on Earth. I'm Laura Knoy. Coming up, getting the gardens of Marrakech to grow green again. First, auto-immune diseases are little understood by scientists. For most of these diseases, there is no known cure, nor do doctors know why people get them.

In two neighborhoods in Boston, public health officials have launched a new kind of study to help unravel the mystery. They're looking into why a high number of women are getting connective tissue auto-immune diseases, and wondering whether industrial chemicals are to blame. Rachel Gotbaum reports.

GOTBAUM: Six years ago at the age of 38, Liz Lombard was diagnosed with a rare auto-immune condition called scleroderma. Scleroderma is a connective tissue disease in which uncontrolled production of collagen hardens the skin and can eventually destroy a person's internal organs. Lombard pulls up her sleeve. Her right arm feels like it is made of stone.

LOMBARD: I'm like a mannequin. I'm like this table. I've described it as being a size six in a size four skin. It literally, I'm very hard, I've very tight. My mouth has shrunk. My hands don't function. You see I'm very shiny.

GOTBAUM: Since she was diagnosed, Lombard has lost about 40 pounds because eating has become difficult. Her hands are stiff and her fingers are gnarled. At first, the mother of five thought she was just unlucky. But soon she discovered that several other people who live in her South Boston neighborhood also had scleroderma.

LOMBARD: Ann MacAlly, she was number five. She was the fifth one I found out about, and it blew me out of the water. She grew up five doors away from me. Five doors, in little tiny South Boston. She's five doors away and we both have this rare disease, scleroderma.

GOTBAUM: Epidemiologists estimate that one in about 10,000 people, most of them women, will get scleroderma. In South Boston, a neighborhood of about 35,000, at least 26 people have been diagnosed with the disease, and three have already died. The rate of scleroderma in this neighborhood is seven times above normal.

The illness has no cure, and no one knows why people get it. But a few workplace studies suggest that exposure to solvents found in petroleum and other toxic chemicals could increase the incidence of scleroderma.

[SOUND OF TRAFFIC]

GOTBAUM: Liz Lombard stands in front of an oil refinery a few blocks from where she grew up. Because of leakage, the area has been designated a major hazardous waste site. Lombard points to a nearby beach where she swam as a child. She says there was always petroleum in the water here.

LOMBARD: Yeah, here's the beach. That's Boston Harbor. They call that the lagoon, and we used to swim there, of course, as kids. You didn't have to put on baby oil because you were so greasy when you got out of that water.

GOTBAUM: Lombard also worries about other toxic sites in South Boston, including two power plants on the same blocks. She suspected the incidence of scleroderma in her neighborhood was no coincidence so she decided to contact the Massachusetts Department of Public Health to get some answers.

Dr. Suzanne Condon researches disease clusters for the state. Once she heard Lombard's story, she decided to investigate.

CONDON: I think we know clearly the numbers are a lot higher than they should be. What's less clear is, is it something about the environment itself in South Boston, or is it something specific to the people who live in that environment?

GOTBAUM: Condon's office is tracking known hazardous waste sites in South Boston, and mapping where those sites are in relationship to the homes of people with scleroderma. They are also asking study participants about their occupational experiences, their daily habits, and family medical histories, and they will also interview 500 long-term but healthy residents as a comparison control group. But this isn't the only disease cluster in Boston.

DRAKE SAUCER: My name is Bobbie Drake Saucer. I'm 56 years old and I've been diagnosed with lupus.

GOTBAUM: Bobbie Drake Saucer lives across town from Liz Lombard in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston. Drake Saucer has had lupus for 15 years. Like scleroderma, lupus is an auto-immune disease in which connective tissues become inflamed and can eventually shut down internal organs.

It is estimated that the rate of lupus in Roxbury and surrounding neighborhoods is more than two and a half times higher than normal. When Drake Saucer heard about the women in South Boston, she wondered about women in her neighborhood.

DRAKE SAUCER: We felt we were having the same, or similar, kind of problem in Roxbury, Dorchester and Mattapan because of what we were feeling in terms of all the newly diagnosed cases. We're trying to find out if in fact there is an epidemic, and if there is an environmental link with all these toxic waste sites that are in the community.

GOTBAUM: The state Department of Public Health is also investigating the lupus cluster. The same workplace studies that link petroleum products to scleroderma link them to lupus as well. So researchers are investigating dozens of old gas stations in the area where oil has leaked from large tanks into the soil.

[SOUND OF TRAFFIC]

GOTBAUM: But gas stations aren't the only suspected problem. In the heart of the Roxbury neighborhood, a former electroplating factory has been deemed a state hazardous waste site. It's leaked petroleum and other toxic chemicals into the nearby soil.

Elaine Krueger is a toxicologist with the state Department of Public Health. There are more than 200 hazardous waste sites in the area, and she says proving any connection to disease will be difficult.

KRUEGER: Urban environments are actually quite complicated because you have a lot of electrical conduits and things like that. So that the pollution can go into those other conduits and go in a variety of different directions that aren't easy to predict. So it does complicate how people might actually ultimately be exposed to a site like this.

GOTBAUM: Lupus strikes black women about three times as often as non-blacks. Unlike scleroderma, scientists know that there is a strong hereditary component to lupus, but doctors say that doesn't explain why black women in industrialized countries are much more likely to get the disease than women in Africa. Dr. Patricia Fraser is a geneticist at Boston's Brigham and Women's Hospital who's working with state health officials on the lupus study.

FRASER: If we have a population at high risk for lupus because of inherited tendencies, and they're also exposed to certain hazardous wastes that we think may also trigger lupus, could this possibly cause an even higher rate of lupus in those individuals in those specific neighborhoods?

GOTBAUM: Fraser is trying to tease out the relationship between the environment and lupus susceptibility genes. To do that, she'll identify women in these neighborhoods who do have those genes, but who have not developed the disease. Fraser will then analyze where these women live compared to the women who are sick.

Only a handful of studies have ever shown an environmental link to a specific disease. Dr. Tim Aldrich should know. He's one of the few scientists who travel the country investigating disease clusters. The University of South Carolina epidemiologist says in his 20 years of work with agencies like the federal Centers for Disease Control, fewer than five cases have concluded that a specific environmental exposure was linked to an illness.

ALDRICH: The burden of proof is immense. To go into the public where you have people that, the general term is "are free living"--they eat what they want, they go where they want, they do what they want, and to try to exact some evidence that is so compelling as to meet the requirements for proof, borders on the impossible.

GOTBAUM: That's because disease clusters can also happen by chance. Think of throwing a handful of pennies onto the ground and having them fall into concentrated piles. But Aldrich says the studies can suggest an association between a disease and a specific environmental toxin. Those results can then help direct scientists to further research, like in the case of the two Boston studies.

Liz Lombard, the South Boston woman who spearheaded the scleroderma investigation, says she'll be happy if state health officials can provide her with some answers, but she knows that won't be easy.

LOMBARD: I feel like I started it with this letter. I'd like to see it through to the end, but I know it's going to take a long time, but I feel we don't have a lot of time. And I never really felt a sense of urgency, but after the three deaths in 2001, I feel that sense of urgency; urgency to get some answers before the rest of us are dead.

GOTBAUM: Both the scleroderma and the lupus studies are expected to be completed by next summer. For Living on Earth, I'm Rachel Gotbaum.

[MUSIC]

Regreening the Medina

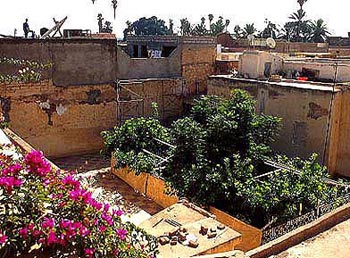

KNOY: Since its founding in the year 1071, the Moroccan city of Marrakech has been an oasis at the edge of the Sahara Desert, a place of rest and comfort for traders from across Africa and Europe. Traditionally the city's old town, known as the medina, has been filled with gardens, but in recent years the population of Marrakech has exploded, and its green spaces are disappearing. As Clark Boyd reports, a group of citizens have now banded together to re-green the medina of Marrakech.

(Photo: © Tor Eigeland)

[SOUND OF MUSIC AND VOICES]

BOYD: Walking through the Marrakech medina, it's hard to believe that this was once known as the “Garden City of North Africa.” Every inch of the old part of the city looks like it's covered in concrete and asphalt, and all of it is constantly buzzing with human activity.

[SOUND OF TRAFFIC]

BOYD: BMWs and horse carts jockey for position on the medina's narrow streets, while in the walkways through the markets, craftsmen busily prepare for the day's business.

[SOUND OF HAMMERING]

BOYD: Historically, a majority of the space inside the walls of the medina was devoted to what western city planners today would call "green space". Residents used the land to plant gardens, fruit orchards, and climbing vines. In the early 1900's, the medina supported a population of about 60,000 people. Now it's home to four times that many residents.

AL ALAWI: As you see, once we go through any of the gates, it really gets--

BOYD: Hicham Al Alawi is a tour guide and life long resident of the Marrakech medina. Alawi says that the population increase began when Moroccans started migrating to the cities a century ago.

AL ALAWI: A lot of people have immigrated from the countryside actually inside the medina because of the drought, because of the economic conditions that haven't been really at the ease of those people, and they were seeking of improving their ways of life.

BOYD: And as the population grew, the green spaces dwindled. In the inner courtyards at the medina's private homes, plants and trees were cut down to make space for shopkeepers. Vegetable gardens that once provided ample food for the people, were dug under when new housing was built on the land. Even the sultan's impressive Royal Gardens, once the pride of all the medina's residents, were left to whither away to dirt as water resources were taken over by the burgeoning population.

Residents like Mustafa, who makes clothing and who has been working in the medina since he was six, bemoan the loss.

[MUSTAFA SPEAKING ARABIC]

MALE VOICEOVER: I remember when there was a huge, shadowy olive tree in the spice market. But they cut it down, because they needed the space. They didn't realize that after they cut it down, they'd have to stand in the hot sun all day.

BOYD: Marrakech natives aren't the only ones who've noticed the decline of the city's gardens. Gary Martin is an ethnobotanist who has lived in Marrakech for 15 years. He fears that the decline of the gardens is affecting the ecological balance of the Marrakech area.

MARTIN: It is the point of botanical diversity, a place of great floristic diversity in North Africa. It's the most diverse area in the Mediterranean basin if you exclude Turkey, and the biological diversity in terms of plant and animal species that you certainly find here, is clearly matched by the cultural diversity.

BOYD: And so Martin decided to try to save the medina's green spaces. He started up a non-profit called the Global Diversity Foundation. With the goal of “re-greening” the Marrakech medina, Martin first turned to Mohammed El Faiz, author of two books on the gardens of Marrakech. El Faiz says that traditional Moroccan gardens weren't just pretty.

[EL FAIZ SPEAKING FRENCH]

MALE VOICEOVER: Sure these gardens were decorative, but they also helped the people by having vegetation: fruit trees, aromatic plants, medicinal plants. There was a functionality to the gardens.

Restoring a home courtyard garden.

(Photo: © Tor Eigeland)

BOYD: El Faiz's knowledge, along with input from residents, helped the Global Diversity Foundation's Gary Martin plan how best to bring back the medina's green spaces. The idea, says Martin, is to try to get people to use whatever space is left for greenery to refurbish the old royal gardens with plants, and to encourage homeowners to once again devote courtyard space to trees and vines.

MARTIN: Let's do re-greening with some of the historically resident species; the things that used to grow there, that grew there for centuries, things like carob trees, grape vines, olives, date palms. These are the things that we really associate with North African civilization in general, and particularly urban areas, and areas in the rural hinterland around cities. And these are the species that are really, if you could call it that, the North African suites of useful species.

BOYD: The municipality is working to insure that enough water flows into the medina so that all these efforts will succeed.

[SOUND OF BIRD CHIRPING, PEOPLE'S VOICES]

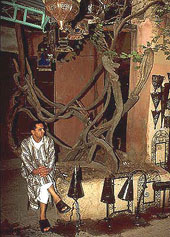

BOYD: In the wool market in the heart of the Marrakech medina a grape vine, or daliya, planted a year ago by the Global Diversity Foundation is now beginning to wind its way up a trellis. It's one of a number of small re-greening projects that are in the works here. The idea is to use small amounts of money to start the initial plantings, and then let the locals take over.

More than 400 women sell clothing here, and they fiercely guard and tend the vine, no one more so than 60 year old Fatima.

[FATIMA SPEAKING ARABIC]

FEMALE VOICEOVER: I water it every evening when the temperature cools off. I also make sure the vine is fertilized, and that the weeds are removed. I tell all the other ladies here to do the same.

BOYD: Fatima and the others say that they can't wait until the summer when they'll be able to sit in the shade under the vine, sipping a cool drink.

This ancient grapevine survives today in the Medina.

(Photo: © Tor Eigeland)

[SNAKE CHARMER MUSIC]

BOYD: They also plan on divvying up the grapes that they grow amongst themselves, a throwback to the old days when the medina's green spaces were shared equally among all. For Living on Earth, this is Clark Boyd in Marrakech, Morocco.

Related links:

- Global Diversity Foundation

- Sustaining the Marrakech Medina (Microsoft Word Document)">

KNOY: And for this week, that's Living on Earth.

Next week, we tour one of the nation's greenest buildings: the new Environmental Studies Center at Oberlin College, and talk with its designer David Orr.

ORR: Thoreau says that Walden, he went to Walden to drive some of the problems of living into a place where he could study them. We've done some of the same here with this building. It's designed to bring some of the problems of sustainability that students will have to wrestle with in the 21st century, here and in this particular place.

KNOY: Green buildings as educational tools, next time on Living on Earth.

And remember, that between now and then you can hear us any time and get the stories behind the news by going to loe.org, that's loe.org.

[LAUGHING GULLS CALLING]

KNOY: Before we go, we'd like to leave you laughing. Lang Elliot recorded this colony of laughing gulls on the southern coast of Maine. They were perched atop an old ship mast that washed ashore on Eastern Egg Rock. The birds obviously thought it was a pretty funny site.

[MUSIC: Earth Ear/Lang Elliot, “Laughing Gull Colony” SEABIRD ISLANDS (Nature Sound Studio, 1996)]

KNOY: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at www.loe.org.

Our staff includes Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Cynthia Graber, Maggie Villiger and Jennifer Chu along with Al Avery, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson, Jessica Penney and Liz Lempert. Special thanks to Ernie Silver. We had help this week from Andrew Strickler and Nicole Giese. Allison Dean composed our themes. Environmental sound courtesy of Earth Ear.

Our Technical Director is Chris Engles. Ingrid Lobet heads our western bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor. Chris Ballman is the senior producer, and Steve Curwood is the executive producer of Living on Earth. I'm Laura Knoy. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include: the National Science Foundation, supporting environmental education, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living on Earth's expanded Internet service, the Ford Foundation for reporting on U.S. Environment and Development issues, the W. Alton Jones Foundation, supporting efforts to sustain human well-being through biological diversity, and the Town Creek Foundation

ANNOUNCER 2: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth