February 7, 2014

Air Date: February 7, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

.jpg)

Oil Addiction Boosts Odds For Keystone

View the page for this story

Environmental activists have drawn a line in the sand over the proposed Keystone XL pipeline, saying its approval would be a disaster for the planet because of the climate disrupting emissions it would enable. Former White House Energy analyst Bob McNally tells host Steve Curwood that Canadian tar Sands oil will come to market whatever the final decision on the pipeline. (08:40)

West Coast Drought

View the page for this story

A lingering high pressure system off the west coast of the US is linked to California’s third consecutive year of drought. NOAA research meteorologist Martin Hoerling explains to host Steve Curwood that the weather pattern causing drought in California is also bringing snow and cold temperatures to the Great Plains and the Northeast. (04:00)

Drought Squeezes California Farmers

View the page for this story

Agriculture in California is a $45 billion a year industry that specializes in crops like almonds, grapes, milk, and tomatoes. USDA meteorologist Brad Rippey tells host Steve Curwood that the state's third consecutive year of drought means farmers will have to make tough choices about what crops to grow and it may cost us at the supermarket. (04:20)

Water 4.0

View the page for this story

Increasing population density and changing weather patterns stress our cities’ water supply, but developing technologies offer positive changes and investments to conserve this most vital resource in coming years. UC Berkeley professor David Sedlak, author of Water 4.0: The Past, Present, and Future of the World’s Most Valuable Resource, discusses future water infrastructure with host Steve Curwood. (07:50)

Rain Tax

/ Julie GrantView the page for this story

The EPA wants to limit the storm water run-off going into rivers and streams to help clean up the Chesapeake Bay. Some towns are charging citizens a fee to upgrade storm drains. As Julie Grant of the Allegheny Front reports, locals call it a "rain tax". (06:15)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Alligators and amphetamines in the Sewers: In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about scientists tracking drug-use via waste water, and reveals the origin of classic urban myth. (04:20)

Eagle Cam

View the page for this story

When a pair of eagles set up house between a parking lot and the athletic center of Berry College in Georgia, school officials set up an eagle cam to keep watch on the nest. Host Steve Curwood talks eagles with Berry College biology professor Renee Carlton. (07:50)

How to eat a Geoduck

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

The Geoduck clam of the Pacific north-west is prized in China, but imports were recently banned after a sample showed high levels of arsenic. Now Seattle restaurants are trying to get locals to eat the huge clam, as Ashley Ahearn reports. (05:25)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Bob McNally, Martin Hoerling, Brad Rippey, David Sedlak, Renee Carleton

REPORTERS: Julie Grant, Peter Dykstra, Ashley Ahearn

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. The state department argues that Keystone XL pipeline or not - dirty tar-sands oil will get to market.

MCNALLY: Oil demand's going to rise by about a third globally and by well over two-thirds in the developing part of the world so we're about to see one of the largest booms in oil consumption ever in coming decades, and Canada has one of the world's largest supplies.

CURWOOD: Some analysts say it's a simple matter of supply and demand. Also, learning to love and eat the geoduck - a huge west coast clam with an unusual appearance.

GIFFORD: This is going to get a little raunchy. It's a very phallic looking animal. So what you do is we bring 'em in, and we let them kind of relax a little bit, let them go down and get out to its natural length.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

Oil Addiction Boosts Odds For Keystone

The proposed Keystone XL Pipeline would carry Alberta tar sands oil to refineries on the US Gulf Coast (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The US State Department's latest Environmental Impact Statement brings approval of the controversial Keystone XL pipeline one step closer. President Obama promised to veto the project to bring over 800,000 barrels of tar sands oil every day from Canada to the US gulf coast if it would contribute significantly to global warming. Now the State Department's confirmed its finding that the oil will reach markets with or without the pipeline, thus approval would have minimal impact on the climate. Environmental activists vehemently disagree, calling tar sands oil a major threat to climate stability. But Bob McNally, who served as an energy and national security expert in the George W. Bush White House, says the State Department has it right. Bob McNally, welcome to Living on Earth.

MCNALLY: Good to be with you. Thank you.

CURWOOD: So there’s been so much tension and controversy over this pipeline project. You’re an energy analyst, why do we need this oil up there in the Alberta tar sands?

MCNALLY: Well, the oil sands in Alberta are the world’s third largest source of oil after Venezuela and Saudi Arabia, and analysts and government officials who’ve looked at forecasts and generated forecasts predict that oil demand’s going to rise about a third globally, and about by well over two-thirds in the developing part of the world so we're about to see one of the largest booms in oil consumption ever in coming decades, and Canada has one of the world's largest supplies. So, it’s basic supply and demand. Those new consumers are going to want to get that Canadian oil, and one way or another, analysts agree, and State Department agrees, that oil is going to get produced and shipped to consumers.

Analysts say that if Keystone XL pipeline doesn’t get built, Canada would likely ship oil from Alberta by rail (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: So the analysis of the State Department says that the oil coming out of Alberta is about 17 percent more carbon intensive than traditional crude oil, what do you think about the Keystone’s impact on climate change?

MCNALLY: Well, the State Department also concluded that the oil in Canada will get produced with or without the permit. If the Keystone permit is rejected, and the pipeline is not built, the oil sands will come to market via other pipelines and rail, which emit more than the Keystone pipeline would. So that’s why I think the State Department concluded, despite the increase in carbon emissions from oil sands relative to conventional oil, that since the oil in the oil sands is going to be consumed anyway, the cleanest way to get it out was to put it through the Keystone Pipeline.

CURWOOD: So you’re saying that, say, putting it in trucks or putting it on rail would be 20 percent more emissions related to this source of crude?

Analysts say that demand for oil will increase until we convert to alternative fuels for transportation. (Photo: bigstockphoto.com)

MCNALLY: Right. The State Department concluded that for other pipelines and rail transport options compared to the Keystone Pipeline.

CURWOOD: How viable are those options though? We’ve seen all kinds of problems with trains, a number of deadly derailment accidents, and as far as an alternative pipeline going through British Columbia, there seems to be all kinds of problems there - local politics and treaty rights with first nation groups.

MCNALLY: Well, I think there’s no question in Canada and the United States, we’ve seen concern about the costs and risks associated with energy production and transport, and those are going to be addressed. But even taking on board the regulatory changes that will be coming, the view of the State Department and most energy analysts that I’m aware of is that at the end of the day, that oil will still flow. Canada is already working on other options, mainly pipelines from the west out to the east to the maritime provinces, possibly pipelines to the west coast and then to Asia and other rail and pipeline options if the Keystone XL Pipeline is rejected.

.jpg)

Keystone protesters outside the White House (photo: Josh Lopez, Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, some scientists like former NOAA scientist James Hansen say if the carbon in the Alberta tar sands gets into the atmosphere, it’s game over for the climate. What would it take for the Alberta tar sands to become the first major fossil fuel reserve in history to be left in the ground?

MCNALLY: I think in order to imagine a scenario in which the oil sands in Alberta was not produced in the coming years, I think the most likely scenario would be a global recession and a huge drop in the price of oil below the cost of what it would take to invest and produce in Canadian oil. So were we to have a worldwide recession, which would, of course, create other problems, then I could imagine a delay in investment in both the production and transport options for that oil. Second, it’s, I guess, possible that global concern about global warming will rise strongly enough in Canada and other countries to block the production of that resource. But I think that’s very unlikely. When I look around the world and look at Europe and look at Australia and look at Japan, I see areas that have been at the forefront of carbon policies and climate change policies pulling back and stepping back as they’ve encountered economic difficulties, not the least of which are high energy prices, particularly in Europe and Japan. So I don’t see any sign of the kind of resurgence and concern about global warming that would translate into public policies that would block the oil sands from being developed in the next few years.

CURWOOD: Now, by your estimates, you say that the world is going to consume a third more oil in the years ahead. What about concerns by those who talk about what’s happening with the climate that we really can’t afford to do that, and that’s the basis of their opposition to Keystone - that we really can’t amp up our burning of oil.

MCNALLY: Right. I think you’ve stated the opposition correctly. The problem is we have a tension here between concerns about the climate implications of burning that much oil, and then, of course, coal and gas would be burned on top of that, on the one hand, and on the other hand we have to realize that oil is the lifeblood of modern civilization. So far, a billion people on the Earth in the rich countries have dominated oil consumption, and we have forgotten how miraculous and wonderful motorization and getting into cars is. If you think about the ’50s and ’60s, every movie, cultural hero, and every other rock n’ roll song was about getting in a car or doing something in a car, and we’ve kind of forgotten that.

But right now, what we have to realize is there are two to three billion people who are just starting to appreciate the joys of mobility - of driving and flying and the other energy services and goods that come from oil. So it’s the strong desire to have what we have, mainly outside the United States, outside of Canada in the developing world, which can only be quenched by oil because, whereas in electricity production, there are alternative sources of generating electricity - natural gas, coal, renewables, nuclear. In transportation, we only really have oil. There is no large-scale substitute for oil in transportation.

Bob McNally, president of the Rapidan Group (photo: Rapidan Group)

CURWOOD: Now, you lay out a business and technical rationale for approving Keystone...what about the politics of this? There’s been tremendous public opposition - people handcuffing themselves to White House gates and that sort thing, going to jail to protest this - politically, what are the risks that President Obama takes if he goes ahead and approves this?

MCNALLY: Well, we have to remember that this is a Congressional election year and the Democrats stand to lose the Senate. Were he to approve the Keystone Pipeline, the environmental groups will be very angry. But the environmental groups want to protect against a Republican Senate just as much as President Obama does. So I think it’s unlikely that environmental groups will withhold political support, financial support, for Democratic candidates this November even if the President approves the Keystone pipeline.

If the President rejects the pipeline, he risks some vulnerable members of the Senate in his own party, such as Senator Begich in Alaska, Senator Landrieu in Louisiana. So the way I look at the politics anyway, the President will be better served if he were to approve it this year. He will take a hit from environmentalists, but that hit will be less harmful and painful this year than it would have been, say, perhaps in 2012 when he was running for reelection.

CURWOOD: Bob McNally is a former Presidential advisor and founder of the Rapidan group. That’s so much, Bob.

MCNALLY: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- Read the State Department Environmental Impact Statement on Keystone

- Read an Analysis of the Statement from InsideClimateNews

- Rapidan Group website

West Coast Drought

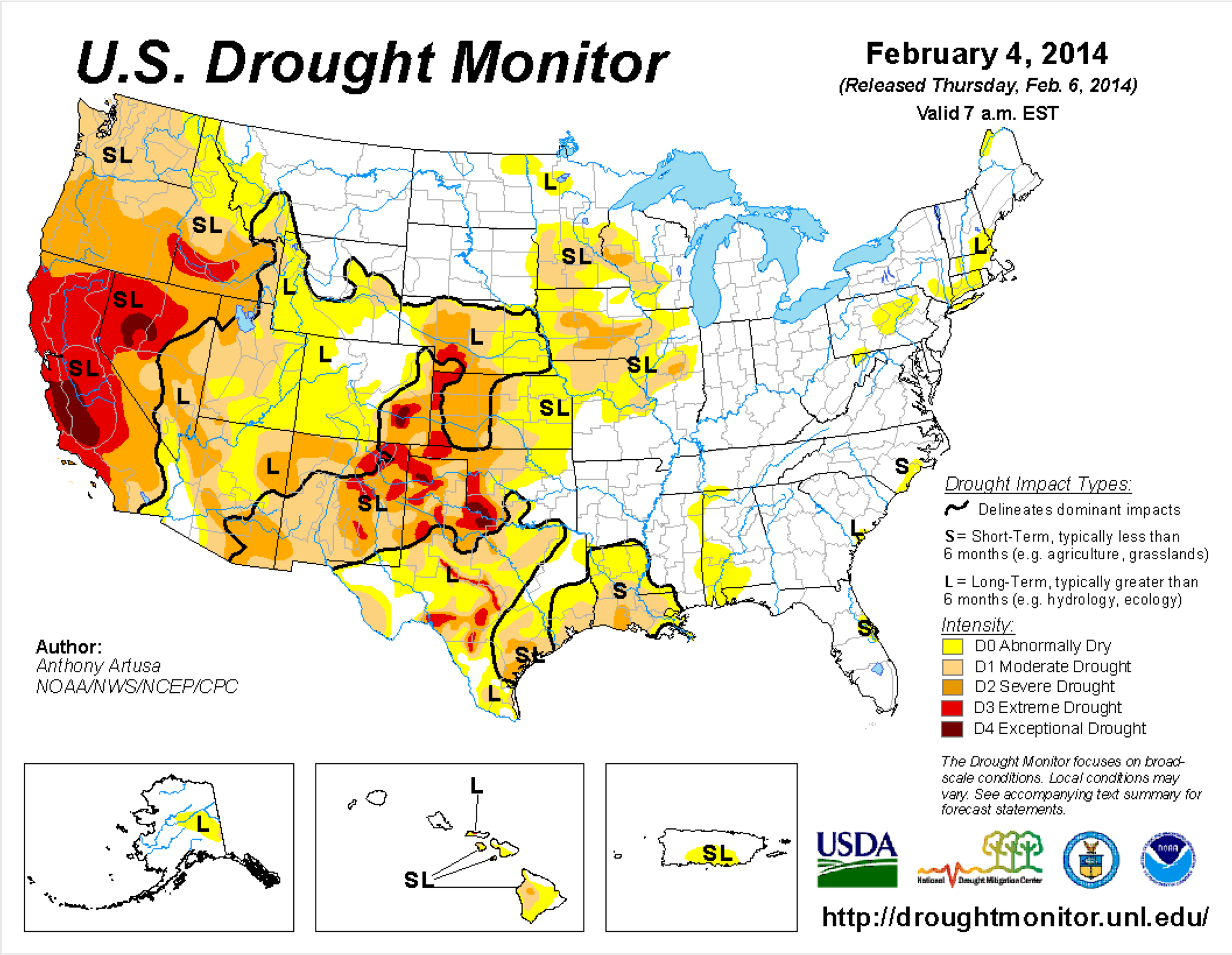

US drought monitor for 2/4/14 (USDA)

CURWOOD: For three consecutive years California has been gripped by severe drought. Governor Jerry Brown recently declared a drought emergency, and restaurants can't even give diners water unless they ask for it. To figure out what's going on, we called Martin Hoerling, a research meteorologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Welcome to Living on Earth.

HOERLING: Pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: So, just how bad is the California drought? How wide an area is being affected?

HOERLING: Well, it’s been quite dry along the Pacific Northwest coast; so basically from Seattle south to San Diego. The drought, which is really in its third year now is at its worst right now. Last year was, of course, also very severe, but it’s been drier this year than last year.

CURWOOD: Can you give me some examples of places that have been particularly affect by this drought?

HOERLING: A station - this is a bellwether station for the accumulation of snowpack in the northern Sierras, which is a very important water supply source for southern California - the station’s name is Blue Canyon, it’s on interstate 80 before you ascend to Donner Summit. Beautiful place. Normally about this time of year, they would have picked up about 30 inches of precipitation. They’ve had closer to about five or six inches. So they’ve gotten into a deep hole. It’s going to be tough to come out of for the rest of this rainy season.

CURWOOD: So at this point, what’s causing the drought?

HOERLING: Well, the immediate cause is that there is a pattern of circulation in the atmosphere, a high pressure. Some call it a ridge. It blocks the typical storms that like to move from west to east across the Pacific Ocean. These storms have not found their way into California this year. They didn’t do that very well last year either except for December. The storms are finding their way into the Pacific Northwest, far northwest, British Columbia. There’s been landslides of snow, in fact, if I can call it that, avalanches in Valdez and places along the Alaskan coast, abundant storms as far as the north, but not in California.

The American side of Niagara Falls froze during the polar vortex. The resilient ridge in the Pacific Ocean causing drought in California may also be a factor in colder than average temperatures in the Northeast. (NASA/ Michael Muraz)

CURWOOD: It always seems like we’re hearing about drought out west. How does this year’s drought compare to what’s been going on in the past?

HOERLING: Well, drought is no stranger to this area. The drought this year has been severe, very severe, no doubt about it. But the season isn’t over yet, so we’re a bit premature to sort of log this one in the books. There are two consecutive years that stand out in memory that go back only about 35 years that most people will remember, 1976-77 winter and 1977-78 winter. Those two back-to-back rainy seasons were the driest consecutive two years on the record for the statewide average of California.

History has indicated it may be dry for a consecutive string of four, five maybe even six years and then suddenly pop out into a wet regime. The key here is that the time series does not show a trend of precipitation - either upwards or downwards - over the last 117 years. So cycles of fluctuations that are really quite severe from time to time are the norm in the state. And this is probably another one of these natural cycles that come and go.

CURWOOD: In other words, it’s just...tough weather.

HOERLING: It’s just tough weather, tough love from nature. And it’s also interesting that the drought situation in the west, in California, is linked with the very cold conditions in the east. The weather pattern itself is not just a local pattern sitting off the west coast and affecting only California. As that high pressure has been anchored off the west coast, there’s low pressure around the Hudson Bay region that has been diving southward bringing very cold air into the northeast. So these patterns have been linked. In 1976 and 1977-78, those were very cold winters in the US, they still rank among the coldest winters on record. And again, that was a linkage between the cold in the US in those years and the drought in California. And here we are again, it’s a weather pattern that comes and goes from time to time, and we’re back to a situation we saw about 38 years ago.

CURWOOD: Ah, when there was a great blizzard in Boston in ’78.

HOERLING: Oh, that’s right. Very good. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: Marty Heurling is a research meteorologist for NOAA in Boulder, Colorado. Marty, thanks so much.

HOERLING: Hey, thank you for having me.

Related link:

NOAA on the California Drought

[MUSIC: Nguyen Le’ “Yielding Water” from Walking On The Tiger’s Tail (ACT Music2005)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...feeling the California drought at the check-out counter. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Michael Bloomfield/Al Kooper: “Albert’s Shuffle” from From His Head To His Heart To His Hands (Columbia Legacy records 2014)]

Drought Squeezes California Farmers

Fields for annual row crops such as lettuce and corn may lay fallow in California this year if the drought persists. (USDA)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. The deep drought in California is likely to cut agricultural output this year, and Americans may soon notice, especially in the produce aisle.

Ag is a 45 billion dollars a year industry in California, and Brad Rippey, an agricultural meteorologist at USDA, says California grows a lot more than you might think.

RIPPEY: It's a really interesting list. If you look at the top 10, milk is on top, perhaps surprisingly, if you think about all the other crops. But number two is grapes, we have almonds, nursery plants, cattle and calves, and then the second half of the top ten: strawberries, lettuce, walnuts, hay and tomatoes. And because we have very little snow in the mountains, this is a third year of drought, there are expectations of significant cutbacks in water allocations and supplies for the summer of 2014.

The first to fall will be field crops because that’s an annual crop, you can obviously withhold the water in the field and it would just lie fallow. For some of the more perennial-type crops, fruits and nuts, vines and so forth, you have to water those in the summer to keep them alive so they would receive water but some of the field crops, those fields are going to lie fallow in the summer coming up.

CURWOOD: Now what’s the split of water between people use and agricultural in California?

If water supplies are tight farmers will likely choose to water perennial crops such as grape vines and almond trees over annuals such as tomatoes or lettuce. (bigstockphoto.com)

RIPPEY: As much of 80 percent of California’s water usage is agricultural, and that leaves the other slice of that for a lot of competing interests, including, of course, municipal water, as well as hydro-electric generation, environmental concerns, and then recreational use as well as lake and river levels that need to be maintained for tourism.

CURWOOD: So if 80 percent of the water is used for agriculture, some parts of agriculture use a lot of water. To what extent might California start to rethink its mix of agriculture given the water constraints?

RIPPEY: At this point, some of the more water intensive crops, such as rice, are the obvious ones to be cut back and to move to more either drought-tolerant or lower water use crops.

CURWOOD: California has a well developed system of reservoirs for storing water in times of drought like this. Can you describe that for me a bit?

RIPPEY: Sure, water management has certainly improved in California, but looking at the 154 intrastate reservoirs in California, it’s a tremendous amount of water. A lot of that comes from the Sierra Nevada. Those reservoirs, back during the drought of the 1970s, dipped to less than 50 percent of the average storage. Now, at the end of 2013, California’s sitting in a little bit better position - 70 percent of average storage. However, it’s worth noting that at the beginning of this drought, reservoirs were literally brimming over with about 130 percent of average storage. So in just over two short years we’ve seen that storage drop significantly on the order of 25, 30 percent storage per year. And we could easily see reservoir levels dipping to levels that had not been seen since the 1970s.

CURWOOD: So, Brad, if this drought persists, and farmers in California are forced to grow less, what does that mean for the rest of us who, well, you know, like to eat every day?

RIPPEY: Honestly, for some of these crops California is the primary source. In some cases, like citrus, we can go to Florida, to a lesser degree, Arizona or Texas, but fortunately because the overall US economic engine is pretty well buffered against crises such as drought, the Chief Economist of USDA is indicating that the western drought could have some impact on food prices, particularly fruits and vegetables. But the impact is, at least for 2014, expected to be relatively small. Just to put it in a little bit of perspective, food inflation for 2013 in the US, for all food, was only 1.4 percent. Now looking ahead to 2014, early expectations show food inflation expected to be 2.5 to 3.5 percent, which is pretty much in the range of historical values since the early 1990s.

CURWOOD: Brad Rippey is an Agricultural Meteorologist at US Department of Agriculture. Brad, thank you so much for taking the time with us.

RIPPEY: Thanks for inviting me to join you.

Related link:

USDA on California Drought

Water 4.0

Potable water (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

CURWOOD: Agriculture. Cities. Hydroelectricity. Tourism. Wildlife. There are many competing demands on the scarce water in California. That drought has focussed attention on how we should manage our water supply as populations grow and the planet warms. And a very timely book called Water 4.0 has just been published by David Sedlak, a UC Berkeley Professor of Civil Engineering and Co-director of the Berkeley Water Center.

SEDLAK: I wrote this book because I work in the technical aspects of water supply and water treatment and I would have lots of conversations with people in cities that were contemplating new kinds of water systems, and I was surprised at how little they understood about this hidden system that delivers their water, treats it to make it safe to drink, and disposes or recycles it after they’re done using it.

Water faucet outside of home (Photo: Quinn Dombroski; Creative Commons)

CURWOOD: Professor Sedlak writes over the centuries there was water 1.0, when Rome built aqueducts and disposed of waste. Water 2.0 saw 19th century Europeans chlorinate and filter drinking water; followed by our present system, water 3.0, that treats sewage as well. But David Sedlak say now is time to update to water 4.0.

SEDLAK: Well we're all familiar with one of the first tenets of water 4.0 and that’s water conservation. So, quietly over the last 10 or 20 years, we’ve seen indoor plumbing change as people are switching out their top-loading washing machines for front-loading washing machines, and we’ve saved a lot of water that way. We can do better and we will do better. The other part of water 4.0 involves the creation of local sources of water, and the recycling of water. So those local sources of water are things like capturing urban stormwater runoff. We can also build seawater desalination plants, and those desalination plants can be a new local supply of water. And finally we can start recycling our water, either recycling it close to the home with something like greywater, or we can recycle the sewage after it’s been treated and put it back into the water supply.

CURWOOD: We use perfectly good drinkable water in our toilets. How should we change that system going ahead with what you call water 4.0?

Wastewater treatment plant (Photo: Hasan Zulic; Creative Commons)

SEDLAK: The reason that we put perfectly good water into our toilets is that it’s hard to have two separate types of water coming into the home. So once we built our homes with only one kind of pipe coming into it, and then we got this idea, well, maybe we should put a second kind of water into the house, a recycled water, or a water of lower quality, it became very difficult to re-plumb and rebuild everyone’s houses with a second distribution system. And so, an alternative would be to find a way to get rid of our wastes without using so much water. So the modern flush toilet that many of us have in our homes, uses about 1.5 gallons per flush. It’s possible to reduce that with a vacuum toilet, the kinds of toilets that we’re familiar with on airplanes. So you could reduce the amount of water that the toilet uses to a little less than half a liter if you went to a vacuum toilet. The water savings associated with that isn’t huge, so it may not be a good economic investment. But over time, we may be able to actually get away from putting drinking water into our toilets.

CURWOOD: Now, talk to me about the present drought that is going on in California. With your understanding of what we would need to do to move forward with water, how can we respond to these drought situations?

Rural area water pipes (Photo: Dave Ferguson, Creative Commons)

SEDLAK: The drought that we’re experiencing in California is the worst drought in many decades, but it’s not the only drought. We’ve had a drought in the Colorado River Basin since about 1999, and we recently experienced a pretty severe drought in Texas. I think the drought that is the most instructive to us is the drought in Australia that occurred about a decade ago, and that long drought was cause for major change in the way Australia provided drinking water to people. So the first stage of the drought looks a lot like the first stage of the drought that we see in the western United States. People call for water rationing and voluntary cutbacks and water use, and that gets you through a year or two. But we have to think of something more than just rationing and voluntary cutbacks. We have to start planning for this next generation of water.

CURWOOD: You talk about local water supplies as a way to respond to the threat of drought. Explain more for me.

SEDLAK: It’s nearly impossible to build a reservoir in the middle of a city, but many cities have a reservoir underneath them. They have the local groundwater supply. So, for example, Los Angeles has some wonderful urban aquifers that serve as a source of water supply for the city. So those urban aquifers are like reservoirs within a city, and if we can recycle water and put it back into the ground, we create a local water supply that we can draw upon even during times of drought.

CURWOOD: What do you make of the social and cultural attitude towards water supply innovation. How prepared are we?

Airplane toilet flush, a solution? (Photo: Creative Commons)

SEDLAK: If the system remains hidden underground and people just turn on the faucet and don’t think about all the effort that goes into getting the water to them, we can’t have an intelligent discussion about water supply. And the idea of seeing water as going through a series of revolutions should comfort us a little bit. That is, throughout history, we’ve had problems with our water supply. They’ve seemed difficult and intractable. There have been unfamiliar technologies we’ve had to adopt, and ultimately, we figure it out and we become comfortable with water that’s treated, or having sewage that’s treated, or having water that’s imported. So a lot of the discussions that you hear now and the resistance to new sources of water supply should be expected, by people who are unfamiliar with where their water comes from and why they need to think about something more than the existing system.

CURWOOD: So what do you think it will take for ordinary citizens to realize that a change is needed?

Prof. David Sedlak (Photo: UC Berkeley)

SEDLAK: There’s nothing like a good crisis to bring about change, whether it’s a public health crisis and people dying from typhoid fever and cholera, whether it’s rivers catching on fire and the Great Lakes dying, all of these things prepare the public for the investments and the discussions and the decisions that have to be made about going to a new way of supplying and treating water.

CURWOOD: By the way, I hear reports that the current drought in California’s making the outlook for wine production a little dimmer, and maybe that will galvanize people into action.

SEDLAK: Or might force them to experiment with Argentinian and Australian wines.

CURWOOD: David Sedlak is author of Water 4.0: The Past, Present and Future of the World’s Most Vital Resource. He teaches at UC Berkeley. Thank you so much, Sir.

SEDLAK: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- Check out David Sedlak’s book and video presentation

- David Sedlak discusses the California drought for the San Francisco Chronicle

- More about David Sedlak

[MUSIC: Madrid “Tierra Del Fuego” from Warm Waters ( Aporia Records 2003)]

Rain Tax

Chesapeake Bay (Photo: Craig Strachan)

CURWOOD: Part of the new thinking about water handling involves a decision by the federal government to restrict how much storm water runs directly off hard surfaces into the waterways. For many cities, it’s proving expensive especially in older communities, where culverts are in need of repair. To fix those systems, local governments are starting to charge residents a stormwater utility fee - what some call a rain tax. Julie Grant of the public radio program the Allegheny Front has our story.

GRANT: There’s a big hole in the street in the small downtown of Meadville, 40 miles south of Erie. More than seventy years ago, much of the city was built over the top of streams, which are enclosed in concrete tunnels, called culverts. Assistant City Manager Andy Walker says last summer, when Meadville got hit with a huge rain storm, one of the major tunnels clogged.

WALKER: Essentially, the culvert became nearly completely plugged, with sediment and debris, rocks, branches. Some from the storm itself, and frankly some from prior events where we haven’t done proper maintenance.

GRANT: A third of the downtown streets flooded. Cars couldn’t get through. The water gushed over and under the roads with so much force, iron manhole covers were pushed up more than six feet off the ground. Six months later, Meadville is still recovering.

Walker stands by the hole on Market Street. He says the city had to dig up the street, to get to the underground tunnel. Then they had to figure out how to remove the branches and rocks that were plugging it up.

WALKER: This is where we had opened it up to literally drag out the debris. And we had a pulley system, and dragging a bucket, so we can get it to this hole, and then scoop it up with a traditional backhoe, and then load it out.

GRANT: The $150,000 price tag may not sound bad, but for a small city like Meadville, it’s a significant portion of the budget. Thankfully, Walker says, they don’t have to spend money from the general fund. Last year, Meadville started charging residents a stormwater utility fee, to pay for maintenance, and for projects like this. Many call it a ‘rain tax,’ but Walker doesn’t like that term.

WALKER: And, in fact, we try not to call it a ‘tax increase,’ because in fact it is a user fee.

GRANT: Walker says like any other utility water or sewer people are billed by how much they use it. In the case of a stormwater fee, property owners are charged based on the footage of impervious surfaces, such as parking lots and rooftops, on their property. He says rainwater runs off of those surfaces into the public stormwater system.

WALKER: Depending on the size of your parcel, that’s your billing unit, that’s your impact, that’s your usage of the system, and you’re billed accordingly then.

GRANT: Last January, the average homeowner started paying a new fee, about $90 per year in Meadville. Cities such as Philadelphia, and Mt. Lebanon, south of Pittsburgh, have started charging similar fees.

More Pittsburgharea municipalities are expected to start considering a stormwater fee this year. We asked a few residents about it at a drug store on the East End. Matt Marquette is lawyer, and a homeowner on the east end.

MARQUETTE: I would support any measure that helps develop the infrastructure and limits any sort of pollution that goes into the river waters, which I think are a great local resource.

GRANT: But others we asked don’t want a stormwater fee. In the greeting card aisle, Cheryl Fuller stopped to disparage the idea.

FULLER: We don’t need another bill, we have enough. As homeowners, gas, light, water, sewage. And now a sewer fee? No. No. It’s time to become a renter.

GRANT: The state of Maryland recently passed the country’s first statewide stormwater fee. It’s expected to cost the average homeowner around $175 dollars a year.

[FOX NEWS THEME MUSIC ON TV]

WILLIS: Taxing rainwater. I know it sounds crazy, but that’s exactly what the state of Maryland is doing, creating a flood of outrage.

GRANT: That’s Gerry Willis on Fox News. Her guest is a county executive from Maryland, Laura Neuman.

WILLIS: So essentially the amount of rainwater that is outplaced by my structure, my building, my house, I get taxed for that. Is that the way it works?

NEUMAN: That’s the idea. They’re thinking the amount of impervious surface on your property, meaning your roof, your driveway, your home will determine the amount of tax that you pay.

WILLIS: I’m telling you, that’s sounds like a ton of dough.

NEUMAN: It is. WILLIS: What kind of money can they raise with this? Boy, they get hooked on that money, they’re going to want even more.

GRANT: Neuman says the stormwater fee is expected to raise $14 billion dollars by 2025 in Maryland. It won’t raise near that much in Meadville, PA. But it’s still a lot of money for some businesses and large property owners to pay.

Cliff Willis is director of the physical plant at hilly Allegheny College. Its stormwater utility bill was more than $70,000 last year. He says not everyone understands why they’re being forced to pay for runoff from their parking lots and rooftops.

WILLIS: In any community, particularly a small community, you’ll have folks grumbling about additional fees, and saying: “Well, we’re just going to move outside of the city limits then.”

GRANT: Willis says there is significant development in a nearby township, outside the Meadville city limits. He says township residents don’t pay for police, fire...or stormwater services. But, as a former municipal engineer, himself, Willis supports the new fee.

WILLIS: I’ve been here about 5.5 years, and on at least 2 occasions, I’ve seen water running down Main Street that is deeper than 6 inches. Yes, there certainly is a need for stormwater management.

GRANT: Meadville has already spent some of the money mapping its stormwater lines. And when a sinkhole appeared in one homeowner’s backyard because of an old line, the city had the $60,000 it needed to build a new one.

Meadville’s Andy Walker says even with money from the fee, they can’t fix all the problems. He says when two inches of rain fell in less than 2 hours last summer, some people wanted the city to clean up water in their homes.

WALKER: And were sort of demanding action, now that they’re paying the stormwater fee. And I had to explain to them, for a storm of that size, no matter what we did you almost can’t throw enough money at the problem to fix and prepare for that size event.

GRANT: Pennsylvania already has a lot of rain and snow, and climate scientists predict larger storms in the coming years. Walker says, even with the new fee, fixing the overloaded stormwater system is going to take decades.

CURWOOD: Julie Grant's story is part of the documentary series, Think Outside the Pipes, supported by the Park Foundation and Penn State Public Media.

[MUSIC: Joe Sample “Rainy Day In Monterey” from Carmel (UMG Records 1979)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...checking in on the eagles that went to college. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Various Artists/Havana Swingsters: Mzala” from Mandela: A Long Walk To Freedom (Original Soundtrack)(Decca Records 2013)]

Beyond the Headlines

According to urban legend, the New York City subways are teeming with Alligators.

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Now let's dig beyond the headlines to find out what else is going on in the world. Peter Dykstra joins us in the studio. He's Editor of the Daily Climate.org and Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org. Hi, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. Thanks.

CURWOOD: So what’ve you got for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, we’ve seen a lot in the news over the past few years about about finding pharmaceuticals in our waterways – that’s everything from caffeine to Prozac – and the reason we find them is that sewage treatment plants are designed to treat living things like bacteria. They’re not designed to treat the chemicals that we might ingest and then get rid of. So some scientists have figured out if you can find legal drugs in sewage, why not trace illegal drugs through sewage. Our EHN reporter Brian Bienkowski put together some data from about 20 studies on this. My favorite one is a chemistry professor at Puget Sound University in Washington State who studied his own campus’s sewage output.

CURWOOD: Now, wait a second. Pot is legal in Washington State.

DYKSTRA: But a lot of things aren’t. Here’s what Professor Sewage found. There’s a huge spike every exam week on campus in amphetamine levels in the sewage. That’s probably not a big surprise for a lot of people who are familiar with college. And the technology to detect even tiny traces of chemicals has gotten so much better in recent years. There have been a lot of studies on illegal drugs traced through sewage in Europe: meth, cocaine, heroin, ecstasy in varying amounts, but one of the constants is it’s usually heavier on the weekends.

CURWOOD: OK, Peter. What about the right-to-privacy here?

DYKSTRA: Well, it’s only a privacy issue if the technology were good enough, and it isn’t, to figure out which home or which individual were donating his or her sewage to science.

CURWOOD: So what else do you have?

DYKSTRA: Well, Steve, you have to feel for the poor town of Valdez, Alaska. It’s been 25 years, 25 years ago, Valdez became synonymous with one of the most notorious oil spills in history. 25 years before that, Valdez was wiped out by an earthquake and tsunami. It was rebuilt up the hill a little further away and out of danger.

CURWOOD: Oy Valdez, huh? So we got the big earthquake in 1964, the Exxon Valdez oil spill almost exactly almost 25 years later in 1989, so it’s almost 25 years again, what is it this time?

DYKSTRA: Avalanches. The Richardson Highway is the only way in and out of town, two weeks starting in late January, following absurdly warm temperatures in the 60s – that’s right the 60s, in January, in Alaska – led to two avalanches. They cut off Richardson Highway, the only road access to Valdez. For two weeks, no cars or trucks in and out of town. But the crisis spawned the obligatory heartwarming story. It was about a couple who risked everything to get their sick cat to a vet in Valdez. They hiked, with the cat, over the two avalanches.

CURWOOD: And I’m hoping the story has a happy ending, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Well, it does have a happy ending, but it had kind of an unhappy middle. Their names are Kristina Clark and Donney Carlson. They got arrested trying to save their cat by hiking over the avalanches. They locked them up, even the cat was locked up in a shelter, but the humans got out, the vet got the cat out, the vet healed the cat and all three are doing just fine.

CURWOOD: So, no catastrophe I guess. So, Peter, what do you got for us on the calendar this week?

DYKSTRA: This is one of my favorites, 79 years ago this week, in 1935, the source is no less an authority than the New York Times, they helped start the urban myth about alligators thriving in New York City’s sewer system – you know what an urban myth is, right?

CURWOOD: Yea, it’s a mythtake.

DYKSTRA: Ow! Well, yes, an urban myth is something from a city that’s not true and this is definitely not true. The story goes back, it was reported the next day by the Times that some kids were shoveling snow in a street in upper Manhattan. They put the snow in a sewer - we’re back to the sewers - and they said they spotted a seven-foot alligator living in the sewer where they dumped the snow. They also said they killed the alligator. They cut it up and burned it before anyone got to see it, but somehow this made it into the New York Times the next day and it’s made it into folklore forever.

CURWOOD: Yes, I guess an alligator’s mostly “tail” so that’s makes a good story.

DYKSTRA: Yes, there you go.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is the publisher of editor Environmental Health News and the Daily Climate.org. Thanks for visiting us here in Boston, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Thanks, Steve, it’s great to see you.

Related links:

- Read the full story of the Alaskan cat rescue

- Follow Peter Dykstra on Twitter

Eagle Cam

A Berry College eagle incubating eggs in its nest. (Berry College Eagle Cam)

CURWOOD: We usually think about having an eagle eye, but in this case we're going to talk about having an eye on the eagle.

CARLETON: That's right!

CURWOOD: At Berry College, in Mount Berry Georgia, they have a pair of eagles nesting on campus and because of the event, the college has installed an “eagle cam” to allow people to watch a live stream of this nest located between the parking lot and the entrance to the athletic center. And joining us today to discuss this is Dr. Renee Carleton, she's Associate Professor of Biology at Berry College. Welcome to Living on Earth, Renee.

(Photo: Eddie Elsberry)

CARLETON: Well, thank you very much and thank you for having me talk about my favorite subject, our eagles.

CURWOOD: So when did you first notice the eagles in the nest?

CARLETON: Well, back in 2012, I had a student come and tell me that he had found an eagle nest on campus. And I immediately thought it was up on our mountain campus. We have a reservoir up there. So I said: “where around the reservoir is it?” And he said: “it’s not there, it’s behind the athletics center.” So I went out and located the tree that the nest was in, and within a couple of weeks started seeing the eagles, and it was very obvious that they were building a nest right here on campus.

CURWOOD: So why did you decide to install a camera?

(Photo: Eddie Elsberry)

CARLETON: Well, eagles are such iconic birds. Everybody loves watching them. The first year when they were nesting, we had crowds of people come to watch, and we initially installed a camera that was pointed at the nest tree, but you couldn’t really see what was going on inside the nest. So, we, with the help of Sony and Georgia Power, installed this nest cam which actually points down into the nest, so everybody can have the eagle eye view of what’s going on.

CURWOOD: So I have the eagle cam up right now. Now if someone wants to look along while we’re talking, go to berry.edu, that’s b-e-r-r-y.edu/eaglecam. She’s sitting on the nest, do I have that right?

CARLETON: That’s correct. She’s incubating two eggs right now.

CURWOOD: And...this is so cool. I can see she’s looking around, and her feathers ruffling just a little bit.

(Photo: Eddie Elsberry)

CARLETON: It is a little breezy today so the ruffling of the feathers is because of the breeze.

CURWOOD: So where’s dad? What’s he doing?

CARLETON: He’s probably off hunting. She stays pretty close to the nest. She’s on it almost 24 hours a day. So he’ll go off and hunt and bring something back for her.

CURWOOD: I imagine you have some rather careless squirrels on campus as well.

CARLETON: Yes. We do have a lot squirrels. We have also a very large White-tailed deer population, although I don’t think the eagles are going to try to tackle one of those guys.

CURWOOD: Now, you originally thought this was out at the reservoir. I mean, how unusual is it for eagles to start camping out right next to where people are living and working?

Dr. Renee Carleton, Associate Professor of Biology at Berry College. Credit: Jon Carleton.

CARLETON: Well, eagles do prefer to be around water. They are primarily aquatic type predators. They like to catch water fowl and fish. This particular location is really equidistant between the reservoir on the mountain campus. There is a river fairly close by. Also, there’s an old rock quarry on campus, and a pair of lakes that aren’t too far from us. So really, this to them, I suppose, seemed to be the ideal place, to be equidistant between all these hunting grounds.

CURWOOD: As I understand it, eagles aren’t all that common in your part of Georgia. Why is that?

CARLETON: Because of DDT, the pesticide, eagles became endangered, and in fact, in the ’70s there were no nesting eagles recorded in Georgia at all. After the Endangered Species Act, and the banning of DDT, the populations were able to rebound. Initially eagles were found primarily along the coast, but because they’ve been able to reproduce successfully, the population numbers have increased and eagles have started to move inland to areas that can support them. And our particular area, this region is very, very diverse in terms of biodiversity. So really, it’s made a very good place for eagles to come. And in fact, this particular nest is the first one that’s documented in our particular county. So it’s really a success story.

CURWOOD: Now as I understand it, these eagles are quite good planners.

CARLETON: So they’ll start tending to the nest in September, come around more and more in October and November. And then they actually start their breeding activities in December. This particular pair had two eaglets last year. We think the first egg was laid right around Christmastime, and then the eaglet hatched in late January and fledged in April. This year, they’re a little bit later. The first egg was laid on January 14, and the second egg was laid on the 17th. So we’re expecting the hatch to occur right around Valentine’s Day.

CURWOOD: Now tell me what happens. Hopefully these eggs will hatch soon...Valentine’s Day you’re projecting. What stages will the hatchlings go through that people can see on the eagle cam?

CARLETON: After they hatch, we’ll probably only get some very brief glances of them because at first, young eaglets don’t have the ability to maintain their own body temperature. So they’re going to rely on mom to keep them warm, and she’s going to nestle down right on top of them and keep them comfortable for about a week to 10 days. And then as their feathers start to come out more and they’re able to control their body temperatures, both adults will go and find prey items to feed the eaglets. I think what most people will really enjoy watching is when parents are feeding the eaglets because they’re really very careful. You can imagine this big large bird with the talons and the bill. They will actually fold their talons into the foot, so when they come in for landing at the nest, they don’t accidentally spear one of the eaglets. And then they’ll very carefully pick off small pieces of meat to feed the babies. So they’re really excellent parents, and I think people will really enjoy watching that.

CURWOOD: Renee, what do you hope people will gain from this camera?

CARLETON: I think it will give everybody some real insight into what goes on in eagle life, especially how fast they grow and what kind of steps parents have to do to insure that the eaglets get enough food in order to survive. And what it’s like to be up in a tree that sometimes is swaying quite a bit with the wind. But it’s just a real unique chance to get to get personal with our national symbol, and I think one of the most beautiful birds on Earth.

CURWOOD: Well, Renee, I want to thank you for taking this time today, and for looking after these eagles.

CARLETON: Well, it’s my pleasure to be able to give you some information about them. I hope everybody will check out the cam and get a chance to see the eagles in action and enjoy what almost what has become commonplace for us.

CURWOOD: Dr. Renee Carleton is an Associate Professor of Biology at Berry College in Mount Berry, Georgia. Thank you so much.

CARLETON: Thank you.

Related link:

Berry College Eagle Cam

[MUSIC: Eric T “Fly Like And Eagle” from The Love You Wanted (Steel Dog Records 2007)]

How to eat a Geoduck

Geoduck crudo is on the menu in Seattle. (Photo: Ashley Ahearn)

CURWOOD: Back in December, China banned shellfish imports from most of the US West coast over health concerns, including a high level of arsenic in one sample. The ban has hit folks who harvest the geoduck especially hard. These giant long-necked clams can live more than 150 years and are a delicacy in China‚ but in America, not so much. And with the export market on hold, clam diggers are looking for customers closer to home. In Seattle, Ashley Ahearn from the public media collaborative Earthfix, headed to a popular local restaurant that’s promoting the geoduck.

[INSIDE RESTAURANT KITCHEN]

GIFFORD: My name is Michael Gifford we are at How To Cook a Wolf in Seattle, Washington.

AHEARN (on tape): And what are you doing right now?

GIFFORD: Cooking geoduck.

AHEARN: Gifford lines up the fist-sized clams on a shelf above the sink. Their necks drape down a foot or so over the edge, a yellowy-brown sheath maybe an inch or two thick.

GIFFORD: This is going to get a little raunchy. It’s a very phallic looking animal. So what we do is we bring them in, let them relax a little bit, let them go down and get out to its natural length.

AHEARN: Ahem. Natural length for a geoduck is usually around three feet. Gifford drops a clam into a pot of boiling water for a few seconds and then...

A 6.53-pound Geoduck nicknamed Moby was dug up near Discovery Bay. (Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife)

[ICE SCOOPING SOUNDS]

GIFFORD: Into the ice water. Let that cool down. We don't want to overcook it.

AHEARN: The clam visibly tenses up when Gifford drops it into the ice water. You can see the shriveled skin start to separate from the rigid neck of the clam.

GIFFORD: There we are (peeling off skin) almost like a snake when you find a snakeskin. It’s like wow – is it really that long? But there you go.

AHEARN: The skin of every single clam had amounts of arsenic above China’s safe levels.

The rest of the clam's body parts, like the neck, the mantle and the gut ball, were OK, except for one sample.

DEWEY: First step is always to remove the skin so we haven’t found any recipes or any suggestions that eating the skin is appropriate.

AHEARN: Bill Dewey is a spokesman for Taylor Shellfish. They're one of the largest shellfish company in the country, based here in Washington. He says the company has had more testing done on several different kinds of shellfish it sells. The levels of metals are all very low and some of them are naturally occurring, but they're there.

DEWEY: You will see arsenic, cadmium, selenium, all sorts of different metals some good for you some not good for you in all your shellfish.

AHEARN: The Department of Health rigorously tests shellfish for biotoxins and bacteria, but it doesn't regularly test for metals. Past tests from the DOH have shown metals in shellfish at levels below public health concerns. But as with all things, it’s a question of how much shellfish you eat, and some Indian tribes and Asian immigrant communities eat considerably more shellfish than the rest of the population.

[CHOPPING]

Michael Gifford slices delicate strips of geoduck flesh off the neck of the clam.

[CHOPPING]

Now he's finely mincing Fresno chilis and celery. Then he smears a green stripe of avocado puree across the plate. Gifford arranges the geoduck in pearly ruffles atop the avocado green and sprinkles some olive oil.

GIFFORD: A little bit of lemon. We use fleur de sel, a very nice sea salt. And then we'll get to eating. So, for your first one. For your first time. Please.

AHEARN: Gifford hands me a forkful of geoduck.

AHEARN (on tape): Wow.

GIFFORD: Like clams on the half shell. The texture, it's tender but there’s chew to it.

AHEARN (on tape): I was kind of expecting rubbery, looking at them from the outside. It's a lot more subtle.

GIFFORD: It's not full of brine, but you're getting that saltwater, you're getting the ocean.

AHEARN: Gifford remembers his first experience with geoduck. He had it at a sushi restaurant soon after he moved to Seattle from New Jersey.

GIFFORD: It was a great introduction, I was like - wow, I've never seen this before. It's really unique. We're very fortunate here to have this product.

AHEARN: But people didn't always feel this way about geoducks, says Bill Dewey.

DEWEY: In the ’50s, you'd be hard pressed to find geoduck on a menu, maybe on the Hood canal in the Geoduck Tavern, but in Seattle restaurants probably not too much.

AHEARN: Dewey says Taylor Shellfish has been actively promoting geoduck to restaurants around the Northwest. There are now close to 20 restaurants in Seattle with geoduck on the menu.

But the domestic market isn't making up for the industry's losses abroad. Geoduck can sell for close to $100 per pound in China. Seattle restaurants pay around $20 per pound, and as the ban drags on, Dewey says Taylor Shellfish and others have had to make some tough cuts.

DEWEY: We did our best through the holidays to keep people employed, shifting them to other jobs, doing maintenance work on the farms and so on, but ultimately it's gone on long enough that we've had to lay some people off here a couple weeks ago.

AHEARN: Taylor laid off 14 people and estimates its losses at upwards of a million dollars. Geoduck harvesters with the Suquamish and other tribes are slowly getting back to work, selling clams to other Asian countries. The Department of Natural Resources is out close to $1 million in revenue from geoduck harvested in state waters. Dewey says he's optimistic that China might lift the ban soon. But the federal government said there is no timeframe for that, and they have not had an official response from China.

For now, Geoduck may still be a tough sell for Northwest foodies, but if more chefs like Michael Gifford have their way with this quirky clam, the future might look a little more delicious.

I'm Ashley Ahearn in Seattle.

Related link:

Earth Fix

[MUSIC: Third World “Jah Glory” from 96 Degrees In The Shade (Island Records 1977)

R.I.P. William “Bunny Rugs” Clarke 02/06/1948 – 02/06/2014]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Clairissa Baker, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Catalina Pire-Schmidt, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of The Nation, where you can read such environmental writers as Wen Stevenson, Bill McKibben, Mark Hurtsgaard and others at TheNation.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth