February 27, 2015

Air Date: February 27, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Presidential Hopefuls and Climate Change

View the page for this story

As the planet heats up, so does the race for the 2016 presidential election. The National Journal’s energy reporter Clare Foran talks with host Steve Curwood about leading Republican contenders and their views on climate change and how that could impact their viability as candidates. (10:20)

Harvard Divestment Case In Court

/ John DuffView the page for this story

On February 20th, 2015, Harvard students got their chance in court to plead their case for the university to dump its fossil fuel investments. University of Massachusetts Environmental Law professor and Living on Earth’s Fellow John Duff was in court, and tells host Steve Curwood about the hearing and the broader context of the case. (04:40)

Stewardship Saturdays in Boston Harbor

/ Olivia PowersView the page for this story

Boston’s Harbor Islands offer a scenic retreat from the bustle of the city, but they’re vulnerable to invasive plant species that displace native flora. Living on Earth’s Olivia Powers visited Grape Island on a “Stewardship Saturday” to watch young conservationists get rid of invasive buckthorn. (07:05)

The Federal Animal Killing Program

View the page for this story

For more than a century, a US federal program called Wildlife Services has been operating in the shadows. It’s funded by private interests and taxpayer money, and now kills millions of animals — some inhumanely. As the Center for Biological Diversity’s Amy Atwood explains to host Steve Curwood, this slaughter is too often not in service of the animals or ecosystem, and has little regulation, transparency or accountability. (06:45)

Ancient Wheat and the Rise of Agriculture

View the page for this story

The discovery of 8000-year-old wheat DNA off the coast of the UK has archaeologists rethinking their theories about the rise of agriculture in western Europe. University of Warwick professor Robin Allaby tells host Steve Curwood that Britain’s hunter-gatherers were not isolated as had been thought, but probably interacted and perhaps traded with European farmers. (13:30)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about a climate denial funding scandal and the 104th anniversary of the Weeks Act. (04:55)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: STEVE CURWOOD

GUESTS: Clare Foran, Amy Atwood, Robin Allaby

REPORTERS: Olivia Powers, Peter Dykstra, John Duff

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The majority of the American public wants government action on climate change, but likely presidential candidates vary across the political spectrum.

FORAN: Most Republicans will say that the climate is changing right now, but that's about as far as they'll go. When you start asking whether or not human activity contributes to climate change and if we should do anything about that, most Republicans right now are sort of sidestepping or dodging that question.

CURWOOD: Also, the volunteers who grub out invasives that are displacing native plants on Boston’s harbor islands – as a way to reconnect with the past.

ALBERT: Native Americans utilized staghorn sumac for millennia here in the harbor islands. And without the staghorn sumac being present, it’s hard to feel and understand the deep history of this place.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

[THEME]

Presidential Hopefuls and Climate Change

In an interview with ABC TV in 2014, Senator Marco Rubio said he doesn’t believe human activity is contributing to climate change, and said he doesn’t believe there are actions that should be taken now to address it, though he does see value in alternative energy and energy conservation. (Photo: Gage Skidmore; Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. As the 2016 race for the White House begins to click into gear, one issue that sets members of the crowded Republican field apart from one another is climate change. Recent polls show that the majority of Americans think climate change is happening, humans are playing a role, and the government should do something about it. But few of the Republican presidential hopefuls say the government should take action. To assess where the likely contenders stand, we turn now to National Journal energy reporter, Clare Foran, who looked at the records and statements of the field, and recently wrote an article called the "Guide to Republicans and Climate Change." Clare, welcome to Living on Earth.

FORAN: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: Now, Clare, you're familiar with the polls that shows the majority of the public would like to see their public officials taking action on climate change in one way or another. How does this perspective of the general public compare to the positions that various politicians and candidates have been taking on the issue?

Last month, Senator Ted Cruz voted against an amendment that stated human activity contributes to climate change. (Photo: Gage Skidmore; Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0)

FORAN: Well, there really is sort of a drastic gulf between where the majority of American voters are and also the majority of Republican voters and where their elected officials are on this issue. Now, there is of course a marked split between Democrats and the Republicans in office right now when it comes to their stance on climate change and with likely Democratic presidential contenders like Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, on the Democratic side there seems to be unanimous belief that climate change is real, human activity is contributing and we need to do something about it.

CURWOOD: And what about the Republican side?

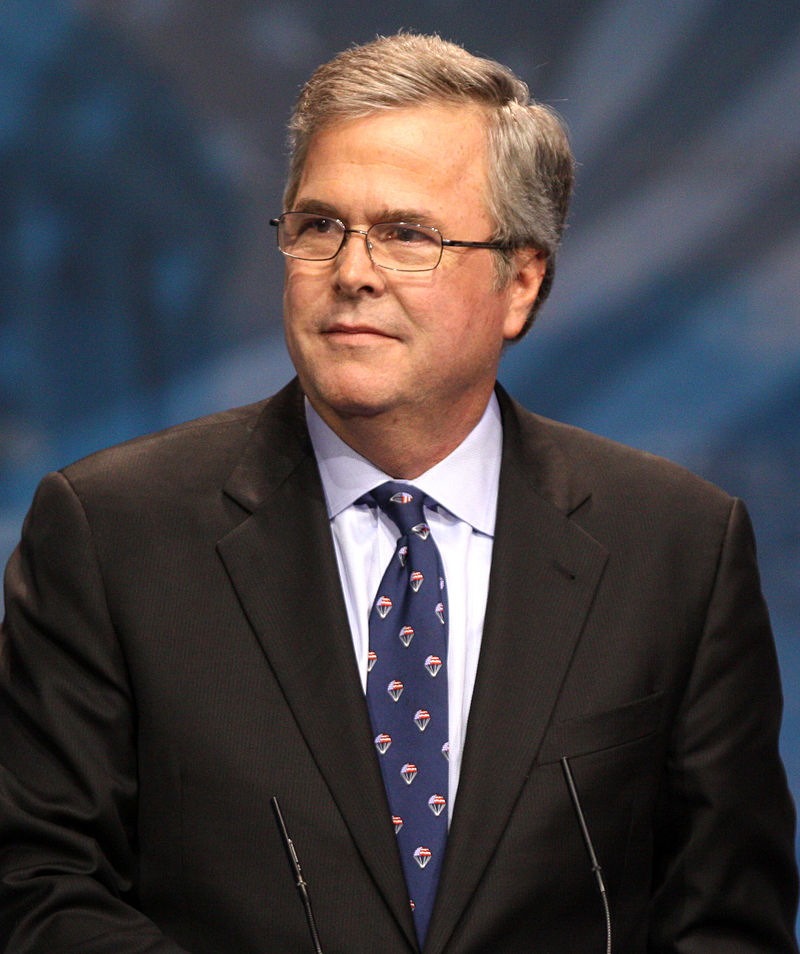

FORAN: It's a completely different scenario. Most Republicans will say that the climate is changing right now, but that's about as far as they'll go. When you start asking whether or not human activity contributes to climate change and if we should do anything about that, most Republicans right now are sort of sidestepping or dodging that question. A lot of high-profile Republicans - so including people like Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz, Jeb Bush - they'll sort of say, "We don't really know if human activity is contributing," or, "I'm not sure," or, "That's an open question".

CURWOOD: Which of the Republican field is adamant that this is a hoax?

Senator Rand Paul says climate change is real, but is unclear what he would about it. While he is not opposed to environmental regulations that protect air and water quality, he sees the Obama administration’s power plant emissions caps as damaging to the economy. (Photo: Gage Skidmore; Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

FORAN: You're really not seeing many Republicans saying that climate change is a hoax, which is a marked change from about a year ago. People are less willing to say that it's a hoax, but when you ask them what causes it that's where they start to dodge.

CURWOOD: Now, from your work, which of the Republican candidates for president, wanna-be or likely, are saying that we should do something about climate change?

FORAN: So there are several prominent Republicans that do say we should do something about it, but that being said, nobody has really offered a concrete policy proposal. But when we talk about Republicans who say we should act on climate change you're going to see people like Lindsey Graham, a Republican senator who said he's exploring a 2016 bid, Bobby Jindal has also talked about how we should do something to cut carbon emissions, and finally Chris Christie said that it's unequivocal human activity contributes. Sen. Rand Paul has also talked about how we need to cut pollution, but has been less definitive in what he means by that.

Bobby Jindal has said that we should do something to cut carbon emissions – but exactly what he thinks should be done is unclear. (Photo: Gage Skidmore; Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: So that's an interesting group of candidates there. We've got Bobby Jindal. Of course, Louisiana went through Katrina, and then Chris Christie that suffered through Superstorm Sandy and Lindsey Graham, of course, who had signed on to the cap and trade legislation with John Kerry when they were both back in the senate in 2009. So it's kind obvious why those folks would agree, but Kentucky's Rand Paul? Why was he jumping into this, do you think?

FORAN: Well, I think Senator Rand Paul is opposed to the Obama administration's efforts to rein in air pollution from power plants, but he's also made statements saying that he's not universally opposed to environmental regulations. He thinks that environmental regulations have dramatically made air and water cleaner in the United States, but he just doesn't want to see a policy that kills jobs. So it's sort of unclear whether or not he would support any environmental regulation to cut carbon omissions in the future, or whether he wouldn't, because he would say it would be job killing.

CURWOOD: It's very interesting that he is even talking about it because of course Kentucky mines a lot of coal.

Chris Christie has stated that it’s unequivocal that human activity contributes to climate change and agrees action is needed. (Photo: Gage Skidmore; Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

FORAN: That's true, and if Rand Paul were to stake out a position on this issue it could erode support for him in Kentucky where he faces reelection to the Senate in 2016, but on the other hand he's shown that he's willing to buck sort of the establishment Republican line on other issues like national security and drug policy and it's possible that he might do the same on climate change - it just remains to be seen. If he were to sort of eke out a position on climate change that is not hostile to government action to address it that might be a way for him to win over younger voters or even independents who polling suggests strongly would back a candidate who says we need to do something about climate change.

CURWOOD: Now, what about those Republicans who say they are unclear about the cause of climate change, and if anything should be done about it? Who is in that camp?

FORAN: Well there's a number of Republicans who fall into that camp. Marco Rubio, last year he made comments in an interview with ABC where he said he did not believe that human activity was contributing, but then not long afterwards he somewhat walked back those comments by saying that he thinks that it's an open question if human activity is contributing. Ted Cruz has also been skeptical that human activity contributes and, in fact, last month in the Senate there was a series of votes asking senators is climate change real...does human activity contribute? And there was a noticeable split between Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz and Rand Paul where Rand Paul voted for an amendment that said human activity contributes to climate change, and Rubio and Cruz voted against that same amendment.

Rick Santorum has taken one of the most vocal positions against doing anything about climate change. (Photo: Gage Skidmore; Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: What about some of the other candidates like Scott Walker and Rick Santorum?

FORAN: Scott Walker has really not put himself on record at this point on whether or not human activity contributes to climate change and if we should do anything, but if you look at other actions he's taking, he's promised to fight tooth and nail against the president's regulations to curb air pollution and that the rule is going to have a devastating impact on Wisconsin. Then when you look at somebody like Rick Santorum, he's taken one of the most vocal positions against doing anything about climate change on the Republican side of the field. When asked by CNN should the United States do anything about climate change, Santorum replied clearly “no”, going on to say that action by the US is not going to make a dent when we have nations like China and India just belching out coal and air pollution.

CURWOOD: What about Rick Perry? I'm not sure he's getting into the race this time, but he has made some noises.

FORAN: Last year he said that he did not think that carbon dioxide should be called a pollutant. Perry also said last year that he's not a scientist, but in the short term he's substantially more concerned about national security issues than he is with climate change.

Jeb Bush’s position on action to deal with climate change is unclear at this point of the campaign, though he has stated it is real. (Photo: Gage Skidmore; Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Clare, of course, you are a journalist, but just imagine for a moment that you are a political adviser to these Republican candidates. How would you suggest that they position themselves on the issue of climate to not only get through the primary process, but also be in a position to win the general election?

FORAN: So if they were to have a strong record on climate change saying that they support action to address it, in the general election that might be something that would help some ward off criticism from the Democratic contender, but for the primary it's a completely different landscape. Right now it's shaping up to be a very crowded Republican primary field. Strategists that I've spoken with that have said it's very likely that the different contenders will be looking for anything that they can attack other Republicans on, and if a candidate has started to eke out a record on climate change that that could really sort of land a target on their back.

CURWOOD: How much do you think at the end of the day voters care about climate in comparison the others issues that they might be voting about?

FORAN: It's a very kind of broad and intangible concept and it's the type of thing where when a pollster asks an American one-on-one, “do you care about climate change?" We do see that a majority of Americans are likely to say, "Yes, that is an important issue, and yes I'd like to support a candidate who wants to take action on it." But when you put that consideration up against a number of other priorities like jobs and the economy, it just really falls to the bottom of the list.

Clare Foran is an energy reporter at National Journal and co-author (with Andrew McGill) of “The Guide to Republicans and Climate Change.” (Photo: courtesy of Clare Foran)

CURWOOD: Which of the Republican candidates, if any, are touting the economic advantages of having new energy regime?

FORAN: It kind of becomes a question of how do you frame the issue. If you ask Republicans if climate change and acting on climate change will hurt the economy, they're likely to say, “yes,” but if you take climate change out of the equation, just talk to them some about renewable energy, they're going to be a lot more likely to support that.

CURWOOD: What about the national security argument when it comes to climate change? The Pentagon has done some research showing that there's going to be some tough national security issues with climate disruption.

FORAN: The military has been saying for years that climate change could pose a significant national security threat, and at least in Congress, Republicans have really not jumped at the chance to fund research or really any kind of programs run by the military that would look into addressing climate change.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think the unwillingness of Capitol Hill to address climate disruption contributes to public skepticism and lack of trust from members of Congress?

FORAN: I think that it does play a role. In the most recent New York Times poll, one of the questions that was asked was whether or not they trust the statements that Republicans in Congress make about global warming, and only eight percent of Republican voters said that they really trusted Republican lawmakers in Congress when it comes time to talk about global warming.

CURWOOD: Clare Foran is an energy reporter with the National Journal in Washington. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

FORAN: Thanks so much for having me.

Related links:

- “The Guide to Republicans and Climate Change”

- “Most Republicans Say They Back Climate Action, Poll Finds”

- “New Congress Has Slightly Higher Ratings, Still Unpopular”

[MUSIC: Andrew Bird, Why? The Swimming Hour Rykodisc, 2001]

CURWOOD: Coming up...the campus fossil fuel divestment movement gets its first day in court. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Alberto Mesirca, Farewell to Stromness, British Guitar Music, Paladino 2012]

Harvard Divestment Case In Court

Harvard law students and plaintiffs Joseph Hamilton and Alice Cherry outside a Suffolk Superior Courtroom for their hearing on motions to dismiss, filed by Harvard Corporation and MA Attorney General's Office against Harvard Climate Justice Coalition and student plaintiffs. (Photo: John Duff)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. As promised, President Obama has vetoed the Keystone XL Pipeline bill, saying it conflicts with established executive branch procedures that allow full consideration of national interest issues such as security, safety and the environment. The massive demonstrations against this pipeline to bring Canadian tar sands crude across the heartland and down to Gulf Coast refineries has helped make the decision both high stakes and high profile. In that, it joins another part of the climate action movement that demands endowments and pension funds get rid of fossil fuel investments.

Another battle line has opened in that confrontation...Harvard students, represented by students at the Law School, have taken the University to court. Their suit claims Harvard’s holdings of fossil fuels violate the University’s mission to educate and advance the well-being of youth, and will bring harm to current students and future generations. The case got its first hearing on February 20 when the University asked a state court judge to throw out the suit on procedural grounds. Living on Earth fellow John Duff is an Environmental Law Professor at UMass Boston and was in the courtroom for the hearing. John, what went down?

DUFF: Well, there were three parties in the courtroom, Steve. The Harvard students were there. They filed a complaint back in November seeking to get a court order to force Harvard to divest of its fossil fuel holdings. Harvard management was there, represented by its attorney, saying that it's up Harvard to make its decision about investments. And the Massachusetts Attorney General's office was there. Their role is to regulate public charities in the state.

CURWOOD: So was there any argument about whether or not climate change is a problem?

DUFF: No, it's really interesting, Steve. All three of the parties and the courtroom agree on some really important things. They all agree that climate change is real. They all acknowledge that it's the result of human activities, and they've all made very public statements saying that something has to be done. In fact, it was the Massachusetts Attorney General's office back in 2007 that led the charge to force EPA to consider greenhouse gases as pollutants because they pose a harm to public welfare.

CURWOOD: So if they all agree that climate change is a problem, what's left argue about?

DUFF: Well, basically the university doesn't want to be told how to make its investment decisions, and the students were also arguing that they should have a right to represent future generations under what they're calling a new wrongdoing, something they call “intentional investment in abnormally dangerous activities”.

CURWOOD: So how did the Harvard administration push back against the student claims?

DUFF: Well, Harvard said that as long as its investment decisions are legal, no one should be allowed to tell them to do otherwise.

CURWOOD: Now, what about the future generations argument?

DUFF: The Harvard students wanted to be recognized as the representatives of future generations, but the fact is they have no legal status and haven't gone to any preliminary steps to be recognized as the guardians or representatives of future generations and the court had a hard time with this because ordinarily to argue on behalf of someone else you first have to be legally recognized. They were trying to do it all in one piece, and the judge was really not amenable to that.

CURWOOD: And the attorney general's office?

DUFF: The attorney general's office said it's their exclusive role to regulate public charities, but the judge mentioned there's an exception to that rule, and the Harvard students took advantage of that exception. They said that they get such a special relationship with the university and that they are going to suffer harm different from the general public that they ought to have a right to bring a case to court.

CURWOOD: So how did the students do when they argued their case?

DUFF: The students had an easier time highlighting their special relationship with Harvard—they are Harvard students after all. But they had a harder time differentiating what harm they may suffer compared to the general public. They were fighting against some longstanding general legal principles. Getting a court to recognize this new wrongdoing doesn't take place at a lower court level. Usually you have to make a claim like that, lose, and get it all the way up to the state high court before you can get a new law recognized.

CURWOOD: So in other words, the students are arguing that it's time for the law itself to change?

DUFF: That's right; they say climate change is a new and different threat and it's time for the law to catch up.

CURWOOD: So if the law is indeed slow and evolving, John, does that mean that the divestment effort is just doomed in the courts?

DUFF: No, there's a long history of the way that the law evolves and usually social movements progress when there is a combination of court action, public demonstrations, and other efforts to shift the cultural landscape. Remember, in 1961, James Meredith had to sue just to get into a university at the University of Mississippi, and he did that as part of a broader context to advance the civil rights movement. And the students are arguing that, like the civil rights era, climate change is something that needs to be addressed on a universal level, and it has to be done now.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth's John Duff is an Environmental Law Professor at UMass Boston. Thanks so much, John.

DUFF: You’re welcome, Steve.

Related links:

- Our coverage of the Harvard Student Plaintiffs’ argument for divestment

- The Missing Campus Climate Debate

- Harvard’s The Crimson covers the divestment hearing

[MUSIC: Leon Redbone, Baby Won’t You Please Come Home. Broadwalk Empire Vol 2 Music from HBO Series. ABCO 2013]

Stewardship Saturdays in Boston Harbor

The docks at Grape Island (Photo: Devin Ford; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s hard to think of summer when there is still so much snow and cold gripping much of North America, and icebreakers have been called in to keep Boston Harbor and other waterways open to boat traffic. We’re dying for a glimpse of green. We’d even take that ubiquitous Japanese knotweed or stinky garlic mustard. But soon enough, we’ll be cursing these invasives, and tugging them out for all we’re worth, including right in Boston Harbor. Living on Earth Olivia Powers has our report.

POWERS: It’s 9 a.m. on a Saturday, but the sun is already hot over the Boston Harbor Islands. A dozen or so volunteers clamber off a boat onto Grape Island. It’s one of the least developed of the harbor islands, with lush vegetation, hiking trails, and campsites, infamously called Tick Island by locals. The park rangers break out heavy-duty cans of bug spray and pass them around as volunteers tuck their pants into their socks.

[SOUNDS OF BUG SPRAY]

Mark Albert rips out some pepper weed (Photo: Olivia Powers)

POWERS: They’re preparing for a full day of hard work with the National Park Service Stewardship Saturday program.

ALBERT: The Stewardship Saturday program got started about 10 years ago now.

POWERS: That’s Marc Albert, the director of the program.

ALBERT: Other park managers and I wanted to offer the public an opportunity to sort of be hands on with helping to take care of the park.

POWERS: The program ferries volunteers out to a different island each Saturday to pull up the invasive species that are crowding out native vegetation.

ALBERT: There’s a lot of invasive species that have changed the ecosystems in a way that we end up with sort of the same mix of invasive species here in the Boston Harbor Islands that you might find in a park outside of Philadelphia or even further to the west and south of here.

POWERS: Albert says that when invasive species move in they threaten ecosystems and destroy biodiversity. And that’s not all that’s lost.

ALBERT: Part of what we’re responsible to do in the National Park Service is to preserve the connections to the past, to help tell the stories of people and how they’ve interacted with places overtime. Probably our signature native species here is staghorn sumac. Native Americans utilized staghorn sumac for millennia here in the harbor islands. And without the staghorn sumac being present it’s hard to feel and understand the deep history of this place.

Volunteer Bob Walsh rips out invasive buckthorn. (Photo: Olivia Powers)

POWERS: Historically, Native Americans soaked the plant’s fuzzy red berries to make a lemon-flavored tea, and dried its leaves to extend their tobacco. Albert says that pulling out the plants that have taken over will help the staghorn sumac return to the islands.

ALBERT: On Grape Island in particular we’ve been working on removing invasive species that are threatening some of the wetland habitats there, and some of the species that occur really throughout the park, such as glossy buckthorn, honeysuckle, and multiflora rose.

POWERS: Today, the focus on the buckthorn, a viciously persistent shrub with small fruits and dark, oblong leaves. Meg is one of the volunteers.

MEG: The easy thing about the buckthorn that we’re pulling today is that the stem is very recognizable. So if you notice the brown stem with the white spots first, then you can double-check the leaves, make sure they’ve got the big veins. And then it’s a matter of tugging on it, trying to find where the root is, and then if you can team up with somebody to try to pull it out and try not to get all of the other plants that are in the area.

POWERS: It’s hard work, but rewarding. Here’s volunteer Ray Watkins.

WATKINS: The little area that we’re standing in right now, we look around us today and we see a little bit of bare ground, and we see a lot of bayberry, which is a native plant to our island plus some berries. And we see we basically cleared this corridor, if you would, down to the water so that visitors to the island walking the path can actually see the water and see down, see what it may have looked like many, many years ago.

POWERS: A few of the volunteers are here for the first time, but most are old-timers like Ray, who return week after week to take care of the islands.

Volunteer Bob Walsh drags away buckthorn branches. (Photo: Olivia Powers)

RAY: I started about nine years ago volunteering with the National Park Service, doing habitat restoration as we’re doing today. There’s a few of us who come out here every week and we strongly believe that we are making a difference.

POWERS: Nancy Faye is another regular. She says she’s lost count of how many times she’s been out on a Stewardship Saturday, but remembers what the islands looked like before volunteer restoration efforts began.

FAYE: I’ve been coming out here since I was a child. It was a way to get away from your parents and just go away for the day and do some adventure, because nobody was out here. It was just raw; it was empty. You would never see another person on any of the islands.

POWERS: The islands aren’t so empty now, but they still offer a refuge from Boston’s teeming streets and looming skyscrapers. And Nancy explains that introducing the city’s youngsters to this world on the harbor’s horizon is another of the program’s goals.

FAYE: I love the educational programs that they do for the kids to expose them to something new. It’s just, it’s so close to Boston and these kids never have an experience to do that.

POWERS: Today, some students from the New England Aquarium’s Live Blue Ambassador program join Nancy and the other volunteers. Here’s Hereesa, one of the high schoolers.

HEREESA: What we do is we focus on habitat restoration and also invasive monitoring. We distinguish, like, an invasive plant, we monitor where they’re growing, what sites they do, and kind of promote the native species to grow and flourish.

POWERS: After lunch, Hereesa and her fellow ambassadors head down to the shore to collect data on the marine life that lives on the ropes that hang off the docks. They’re led by Edgar, one of the park’s staff.

[SOUND OF WAVES]

Volunteers on Grape Island (Photo: Olivia Powers)

EDGAR: We have some ropes here, we’re gonna pull 'em up. These invasive species that we’re looking at are sessile invertebrates, so once they land after their larval form they stay where they are for life so we’ll be able to see if they’re present or not.

[STUDENTS TALKING ABOUT THEIR DISCOVERIES]

POWERS: The rope is covered in slimy sea creatures. The kids pluck them off and drop them in a small bucket. They pull out laminated charts and get to work identifying the different species. The information they gather is passed on to the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management, and will be used to help protect the harbor’s marine resources. Soon, the boat back to Boston pulls up to the dock. The students scramble to grab hold of the railing as the waves hit the dock. After a long day they are exhausted, but giddy, talking about next Saturday when they head to neighboring Bumpkin Island – and what it means to be part of a program working to protect their home. Here’s Hereesa again.

HEREESA: When I grow up I want to you know set an example, and also get out there. I don’t want to be just another person that’s walking on the Earth. I want to make a difference; I want to leave a mark.

POWERS: At least for now, Hereesa will leave her mark, if only on the Boston Harbor Islands, as the work of the Saturday Stewards becomes a new piece of the history that the landscape tells.

For Living on Earth, I’m Olivia Powers in the Boston Harbor.

Related link:

Boston Harbor Islands

The Federal Animal Killing Program

Dogs of Wildlife Services trapper Jamie Olson cornering a coyote caught in a trap. (Photo: Jamie Olson, while working for APHIS-Wildlife Services; courtesy of Amy Atwood)

CURWOOD: Balancing native and non-native species’ involvement in ecosystems is an ever-evolving struggle. But unlike the Stewardship Saturdays in Boston Harbor National Park that operate out in the open, Wildlife Services is a little-known federal program that works in the shadows, culling millions of animals, allegedly with little oversight and regard for humane practices and updated science. Amy Atwood is the Endangered Species Legal Director for the Center for Biological Diversity, which has sued the Wildlife Services Program seeking more regulation, transparency and accountability. Welcome to Living on Earth, Amy.

ATWOOD: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So, first, what is the Wildlife Services Agency?

ATWOOD: Well, what is currently known as Wildlife Services, a name that is very similar to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, an agency of US Department of Interior, is a program that is run by APHIS, which is the Animal Plant Health Inspection Service. APHIS is an agency of the US Department of Agriculture.

CURWOOD: Now, what is the stated mission of the Wildlife Services agency? What services are they supposed to be providing?

ATWOOD: Wildlife Services conducts programs of research, technical assistance and applied management to resolve problems that occur when human activity and wildlife conflict with one another.

CURWOOD: What are the actual services that they are truly providing?

Many traps, poisons and other animal killing apparatuses are placed near and in neighborhoods without the knowledge of the community, thanks for the opacity of Wildlife Services’ codes of operation. (Photo: courtesy of Amy Atwood)

ATWOOD: Wildlife Services is working on behalf of private or specific interests usually from what are known as “cooperators” which can be other federal agencies, state agencies or private agribusinesses to eradicate animals that those industries considered to be pests, so from eradicating carnivore species in order to reduce the amount of predation on sheep or cattle to poisoning or trapping or shooting various species of birds because they consume grain or they damage crops, all the way through to aerial gunning of wolves in remote areas of Idaho.

CURWOOD: So how many animals has the Wildlife Services agency killed? And what kind?

ATWOOD: Wildlife Services reports that it kills millions of animals in the United States every year. In fiscal year 2013 the agency reported that it killed four million animals, two million of those are considered to be native wildlife and the rest are considered to be invasive or non-native. Just to give you a sense, it killed about 25,000 beavers, 300,000 red-winged blackbirds, a thousand bobcats, 20,000 double crested cormorants, 75,000 coyotes. Coyotes actually are the most frequently targeted animal of Wildlife Services with the program reporting that it kills an average of about 400 coyotes every week. Bald and Golden Eagles, black bears, 300 to 500, gray wolves and the list goes on and on from there.

CURWOOD: Wait a second, you said Bald Eagles?

ATWOOD: I did. Now, here we start to encounter the problem with relying on Wildlife Services’ data. The data that the program reports is not even a fraction of the total number of animals that are actually killed. We know that from prior agency employees. And so when we talk about these numbers we have to keep in mind that they are inherently unreliable.

Those employed by Wildlife Services are supposed to check traps like this frequently, but it is known that some individuals will let several months pass before they are checked again, during which time, an animal, if caught, will likely suffer an inhumane death. (Photo: courtesy of Amy Atwood)

CURWOOD: Amy, talk to me about how this agency is funded and your concerns about the conflicts of interest here.

ATWOOD: The total budget for Wildlife Services totals about $115 million a year. About $59 million of that, or a little over half, comes from cooperative funding, and as a result of that there's an inherent incentive for Wildlife Services to be driven in its priorities by the directives of these cooperators. The activities that Wildlife Services carries out are not necessarily what's best for the American public at large or for ecosystems or biodiversity or wildlife in this country.

CURWOOD: You're an attorney with the Center of Biological Diversity. What are you seeking to do?

Many traps, poisons and other animal killing apparatuses are placed near and in neighborhoods without the knowledge of the community, thanks for the opacity of Wildlife Services’ codes of operation. (Photo: courtesy of Amy Atwood)

ATWOOD: Our mission is to protect biodiversity, so in the case of Wildlife Services, we've recognized that although this agency has been around for roughly a century, it has no binding regulatory framework, and so we see a very sort of old outdated way of looking at the role of these animals on the landscape, not to mention entire other federal programs in which the American people are investing millions of more dollars in order to try to protect and recover these animals to their native range on the landscape. And we are demanding that the USDA conduct what's called a federal rule-making to develop a regulatory framework that would bind this program's activities, and we would like to see a fundamental shift in the mindset and the culture of the agency in many areas whether it's from refocusing its efforts away from eradicating incredibly important species from the landscape to eradicating incredibly detrimental species from the landscape. Bullfrogs in the American Southwest are a tremendous threat to the survival of many endangered reptiles and amphibians and they're an invasive species, and while their services is not prioritizing eradication of bullfrogs from the American Southwest, and so where better to redirect the activities of the program like this then toward dealing with problems like that that really threatened to jeopardize and undermine the very fabric of some of the most iconic places in this country?

CURWOOD: How is the US Department of Agriculture senior management responding to your concerns and your call for new rules of procedures to be adopted?

ATWOOD: Well, we have received an official denial from the administrator of APHIS and we are evaluating our options at this point including litigation.

CURWOOD: Amy Atwood is the Endangered Species Legal Director for the Center for Biological Diversity. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

ATWOOD: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Petition to the USDA’s APHIS for Wildlife Services Rulemaking

- Wildlife Services is housed in USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service

- More on Wildlife Services

- Wildlife Services’ directives

- Investigative reporting on the Wildlife Services’ practices

- Lawsuit against Idaho’s large-scale wildlife killing involving Wildlife Services

- Lawsuit Filed Against Mendocino County Over Contract With Rogue Federal Predator Control Program

- An abridged history of the Wildlife Service

[MUSIC: Sting, Fields Of Gold, Ten Summoners Tales UMG 1993]

CURWOOD: Coming up...the surprising discovery of cultivated wheat in the British Isles – two thousand years earlier than anybody imagined. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies, container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Steve Reich Ensemble, Music for 18 Musicians 11, section 1 Nonesuch 2005]

Ancient Wheat and the Rise of Agriculture

Archaeologist Robin Allaby examines wheat. (Photo: courtesy of the University of Warwick)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. The history of agriculture is pretty well established – it was first developed and adopted in the fertile crescent, the part of the middle east that curves from the Persian Gulf across modern Israel and Syria into Egypt. From there it gradually spread across Asia and Europe – reaching the far west and Britain about 6,000 years ago. But a recent discovery of ancient wheat DNA in ocean sediments off the British coast suggests that the grain arrived earlier, about 2,000 years before people began farming it there. Robin Allaby, who studies the evolution of plant domestication at the University of Warwick, was part of the team that made the discovery.

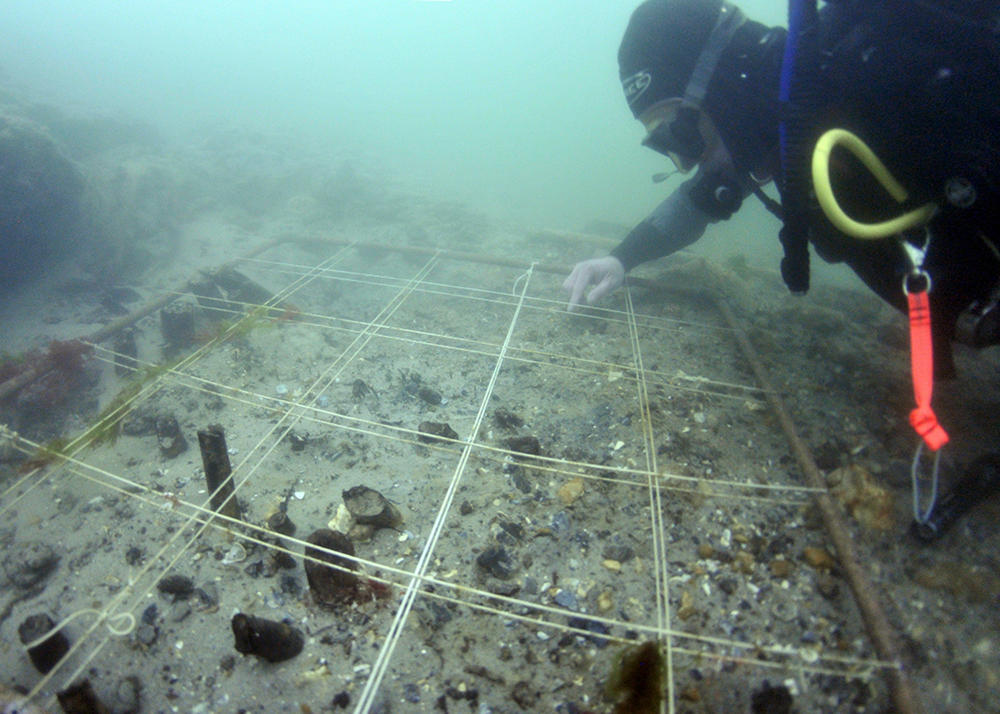

ALLABY: We examined 8,000-year-old soil, paleosoil we call it. That is about 11 meters under the sea off the coast of Britain and it represents the old land surface that existed during a time when sea levels were rising and what we found there was presence of wheat DNA amongst other things, which was incredibly surprising because that's about 2,000 years earlier than one would expect compared to the mainland UK. So, that tells us that Britain at that time was not the insular cut off island that it's conventionally reinterpreted as being, but, in fact, somehow was in contact with the early farmers that were present in Europe and at that time they would've been around about sort of south of France kind of area.

CURWOOD: Now, I understand you isolated this DNA from an underwater archaeological site. How and why did archaeologists zero in on that particular place?

.png)

Divers found traces of 8,000 year-old wheat DNA. (Photo: The Maritime Trust, Roland Brookes)

ALLABY: Well, that's a really good question. We were interested at this site, which is called Bouldnor Cliff, which is just off the coast of the isle of Wight in the Solent estuary. And what the archaeologists have found there is a boat building yard 5,000 years ago. So it's not a settlement where people lived at. They were building boats there. And the technology that they were using to build those boats was actually about 2,000 years ahead of its time, so they were splitting large timbers to produce their boats, and also they had flint technologies and shapes that will more akin to northern France than you see on the mainland UK. So the site itself seemed to be pointing towards Europe with these hints of early technology. So we were looking for a site in which to explore whether we could retrieve environmental DNA, so-called environmental DNA that's sort of free and living in sediments, and what we found is that submarine environments are actually incredibly good preservers of DNA. It's a constant four degrees down there, and the preservation was incredible. So it's like nature's fridge.

CURWOOD: How new is this technique of gathering and analyzing DNA from ocean sediments?

ALLABY: So this was a fairly new approach to looking at environmental DNA, so I think it's only the first or second application of marine sediment DNA analysis, but it's a real breakthrough. It's opened doors to a really exciting avenue of research, not least of which is that it releases latitudinal constraint on where one can do ancient DNA studies from quite considerable time depths because that four degrees, that nature's fridge, is constant all around the world. So we can go down into the tropics where it's notoriously difficult to have preservation of archaeological artifacts for biological DNA for more than a few thousand years, but you can go to the Red Sea for instance and go back tens of thousands of years.

.png)

Robin Allaby says that the cool temperatures of ocean make it great for preserving environmental DNA. (Photo: The Maritime Trust, Roland Brookes)

CURWOOD: So the ocean has more secrets than just its own flora and fauna down there. It keeps some of our secrets as well.

ALLABY: That's absolutely the case, yes. What's become clear from this study is that if you want to understand this process of neolithization, the change to farming in northern Europe, then probably the answers are under the sea, because these events were taking place on areas of land that were subsequently immersed in marine melt water from the glaciers.

CURWOOD: So, for folks who don't have atop of mind the archaeological history of the UK, what were people doing there some 8,000 years ago?

ALLABY: So 8,000 years ago people were living an existence that we describe as hunter gathering, which is how we define what we call the Mesolithic period. So they were hunting game, deer, Aurochs which are giant precursors of cows - grouse - they were gathering plant materials - things like hazelnut and berries and the like. And the difference between that and the emerging Neolithic peoples is that the Neolithic is defined by the growing of plants, so that arable agriculture, wheat and barley in particular.

CURWOOD: Now, how long will it be before people in Britain would start farming themselves?

Underwater archaeologists diving at Bouldnor Cliff off the coast of Britain (Photo: The Maritime Trust, Roland Brookes)

ALLABY: So, we don't see farming on British mainland until about 6,000 years ago, so that's some 2,000 years after the people we were examining at this site at Bouldnor Cliff.

CURWOOD: So this just raises all kinds of questions, this 2,000-year gap. First of all, why might it have taken so long for farming to catch on in Britain?

ALLABY: [LAUGHS] So that's the million-dollar question. The previous conventional thinking about why the Neolithic was late in the UK relative to Europe is that it was thought that Britain was cut off - it was an island. We've established that was not the case 8,000 years ago, and indeed, they were culturally connected. So we have the situation where we have a Mesolithic culture co-existing next to this Neolithic existence and that continues; they maintain their integrity for 2,000 years and the same kind of thing is actually being found in molecular anthropology as well at the moment, so the people that look at the human DNA from various skeletons, they're finding the same thing, that these two cultures are existing side-by-side. So the big question is why didn't the Mesolithic people switch over to a farming economy and there are basically two possibilities: either they didn't want to or they couldn't. And you can find arguments to both of those.

So the surprising thing about the arrival of farming is that it's associated with an absolute crash in health. So we have a lot of our diseases associated with the rise of farming as we come in close proximity to lots of animals, particularly. We're also very malnourished, so skeletons take a crash in size, and we get the development of bad teeth. So it's not hard to see that a person living with Mesolithic would rather stay with their higher calorific lifestyle. The alternative is that actually farming couldn't progress that far north simply because there was a limit to how well the component plants of the agricultural economy could adapt in that latitude as they moved further north. They would have liked to have grown wheat up there but they simply couldn't grow it. It just wasn't ready to be grown as far north as England. And I guess these are the questions to answer now.

Archaeologists diving at Bouldnor Cliff off the coast of Britain (Photo: The Maritime Trust, Roland Brookes)

CURWOOD: So it looks like this wheat that you found there in Britain came from some sort of contact with the south of France at about the same time, but as I understand it the scientific community has been split on whether migrating farmers from the east displaced the hunter gatherers in Britain rapidly or more gradually. What's your view now on the basis of this discovery? What kind of insight does it give you on the transition from hunting and gathering to farming in Europe and the UK?

ALLABY: So what this study shows is that unlike our previous assumptions the Mesolithic people had a contribution to the development of agriculture. They were using the products of the Neolithic technologies, products of farming, therefore, they were cognizant of farming and they knew how to apply its products, so to what extent were they instigators contributing to the rise of agriculture where previously we assumed that either the Neolithic people actually had physically replaced them genetically, so the Mesolithic peoples had died out, were replaced by farmers, or that very quickly the Mesolithic people just took off with the idea of farming. And we know, actually, we know both of those things are wrong. We know from genetic studies of human DNA that European people are actually a mix of Mesolithic and Neolithic, near east in origin DNA, and now we know the Mesolithic people were actually interacting with these Neolithic people, so there was a communication. So, somehow, together the development of farming and therefore, civilization after that occurred.

CURWOOD: One of the things that happens in this transition, you say, though, is there are crashes in the populations, it's not really healthy for humans to shift from hunting and gathering to what we would call modern agriculture. Why do you suppose that is?

Diving at Bouldnor Cliff off the coast of Britain, archaeologists found wheat DNA. (Photo: The Maritime Trust, Roland Brookes)

ALLABY: Probably because with switching from this highly proteinaceous diet to a high starch diet without actually being adapted to obtaining your nutrition and your energy from that particular source. So we know from the human genome that we are evolving to deal with the high starch diet. So, one can look at things like amylase genes, the genes that are responsible for breaking down starch. We have many copies of those genes so we produce more of that enzyme. When you compare it to either a chimpanzee or societies that have always been hunter-gatherers and they have much lower copies of those genes. So we are in a process of adapting to agriculture still, and one really should think of the interactions with humans and plants as a co-evolutionary process. So obviously when we first switched over to that economy it would've been a shock to our system. So we shouldn't be entirely surprised that it wasn't terribly good for us. The big mystery is why we did it, and that's another million-dollar question.

CURWOOD: OK. So let's ask that million-dollar question if it wasn't healthy for us why do we do it?

ALLABY: Well it does permit us to live high population densities. So the difference between a Mesolithic economy and this sedentary Neolithic economy is for one you need a large amount of space and the other one you don't. So it's quite easy or probably inevitable that those that take up this sedentary space - if you've only got a small amount of space - you have to go to an agricultural economy. And as that will naturally spread and that will spread encroaching into a sort of a Mesolithic sort of territory, so it may well have been the case that the Mesolithic peoples of Europe really did not want to switch to an agricultural economy, but at some point they would have had to switch as their own hunter-gatherer economy would have ceased to be viable as they lose more land to this encroaching advancement of arable agriculture.

CURWOOD: So at the end of the day maybe civilization is bad for us.

ALLABY: It could be the case, couldn't it? Clearly it paved the way for sort of this next step in our social evolution. I don't think anybody's going to argue that the rise of cities and civilizations in nation states was bad for us, but it has this sort of interesting contradictive or counterintuitive dynamic that we have to go through, a suboptimal existence. But the fact of the matter is, an agricultural economy worked and we might be less healthy but it can outcompete a hunter-gatherer economy albeit with sickly people than it's going to win out.

CURWOOD: So what comes next for you in terms of research and not only yourself but your team?

ALLABY: So where we would really like to look is the area known as Doggerland. This is the area which is under the North Sea now between Britain and Denmark and Germany which 8,000, 9,000 years ago was Dogger island and then Doggerland, so very fertile land which for the past 100 years or so fishermen have been pulling up the remains of mammoths and bones of giant elk and humans, so we know that there was human occupation of those sites. So those very early stages of the development of the Neolithic probably were occurring out in those regions so where we would really like to go is to look at our stuff to better understand how farming came to Europe and Britain.

CURWOOD: Robin Allaby is a Professor at the School of Life Sciences at the University of Warwick in the UK. Thanks for taking the time to speak with us today, Robin.

ALLABY: It was as an absolute pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Study: Sedimentary DNA from a submerged site reveals wheat in the British Isles 8000 years ago

- Archaeologist Robin Allaby is a professor at the University of Warwick

[MUSIC: Martyn Bennett, Tongues of Kali (edit), 15 from Rykodisc Sampler, Rykodisc 1998]

Beyond the Headlines

Funded in part by ExxonMobil, the American Petroleum Institute and the Charles Koch Foundation, Willie Soon published papers disputing the seriousness of climate change, including one that blamed climate change on the sun, without disclosing the conflicts of interest related to his funding sources. (Photo: Giuliano Maiolini; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Time now to look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. He’s with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org, and he’s on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. It was bound to happen sooner or later. For years, climate deniers have alleged that climate scientists are engaged in a vast cabal to make stuff up in pursuit of money, that what’s disguised as ‘real science’ is actually just a craven and greedy attempt to cash in on all that scientific grant money. Well now, for the first time, a smoking gun, a scientist caught red-handed gaming the system for a seven-figure payday.

CURWOOD: Yeah, that’s been a big story this past week, but of course, there’s a wrinkle.

DYKSTRA: And that wrinkle is a big one because Willie Soon of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics is a go-to guy for climate denial. His work is cited by pundits, and on the Senate floor as solid-gold evidence that climate change isn’t human caused, isn’t a big deal, the Arctic’s fine and that there are enough polar bears up there that you could walk on their backs from Ottawa to Moscow. Or until one of them ate you.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] OK. So walk us through the details.

DYKSTRA: Because of Dr. Soon’s Smithsonian connection, he’s a government guy, and as a government guy, his work and correspondence are subject to the Freedom of Information Act. A group called the Climate Investigations Center, along with Greenpeace, filed a request for Soon’s correspondence, and when the documents were returned they revealed $1.2 million dollars in funding from oil, gas, and coal producers and their affiliates. But there’s more.

CURWOOD: Keep going…

DYKSTRA: Dr. Soon didn’t disclose this apparent conflict of interest on many of the papers he published where he disputed the seriousness of climate change. In many institutions and science venues, it’s OK to take money from someone who may have a stake in the results you report, but you have to be up-front and disclose when you’re cashing checks from an interested party. But there’s still more.

CURWOOD: OK. I'm still here.

DYKSTRA: When corresponding with potential funders, Soon used terms that to me sound a little more appropriate for a used-car lot than for peer-reviewed science. He told an executive for Southern Company - that’s the biggest electric utility here in the Southeast - that he could expect a “super-duper” paper blaming any climate change on the sun, rather than on fossil fuels. And he used the word “deliverables” in describing what other funders, like Exxon-Mobil, the American Petroleum Institute, and the Charles Koch Foundation could expect for their money, and Steve, as many congressional climate deniers have said lately, “I am not a scientist,” but I know that’s not the way that honest science is carried out.

CURWOOD: Well, Willie Soon throwing the sun under the bus as a major cause of climate change is a theory that's been pretty well refuted, so I guess to follow this particular story means you’ve got to follow the money.

DYKSTRA: And the irony in all this, of course, is that one of the attack weapons used against legitimate climate scientists is that they’re getting rich off their work, that they’re only in it for the money. I put together a piece for The Daily Climate last week with ten such quotes, from people like Rush Limbaugh to Senator Inhofe of Oklahoma, the “sooner” state, to Ralph Hall, the former Chair of the House Science Committee.

CURWOOD: And you sent us a piece of tape from another one. Here it is.

CORBYN: They're on a gravy train for heaven's sake. They make trillions of pounds traded every year on carbon trading and doing silly things like building windmills, which achieve nothing. I mean, there's money in it and that has corrupted science.

DYKSTRA: That was Piers Corbyn of the Weather Action Center in the UK.

DYKSTRA: The bottom line is that for all the conventional wisdom out there among climate deniers that climate scientists are corrupted by grant money, and all the efforts made to discredit them, we’re seeing more and more on-the-ground validation that what the vast majority of climate scientists have been telling us for 25 years or more is coming true, and the consequences could be enormous. And we’ve seen no evidence out there that climate scientists are doing their research on gold-plated computers aboard their yachts. But on the other hand, Willie Soon may have a lot to answer for.

CURWOOD: Oh yeah – and that train wreck of money and politics and science and ideology is always so fascinating, isn't it, Peter? Hey, what do you have on the history calendar for us this week?

March 1st marks the 104th anniversary of the Weeks Act, which authorized the federal government to purchase private lands and maintain them as national forests. (Photo: US Forest Service)

DYKSTRA: Well, we’re celebrating the 104th anniversary of one of the first and most important forest protection acts became law. The Weeks Act, sponsored by Congressman and later Senator John Weeks, was a response to rampant logging and the threat it posed to both forests and streams by restricting the cuts and placing sensitive areas off-limits for logging. It was signed into law by a President, who wouldn’t cop out when there was danger all about.

CURWOOD: Taft!

DYKSTRA: Can you dig it? William Howard Taft didn’t have the conservation profile of his predecessor and mentor, Teddy Roosevelt, but he did take this big first step in forest protection.

CURWOOD: So, thanks to President Taft and thanks to you, Peter Dykstra, you're with the Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org. Talk to you next time.

DYKSTRA: Alright, Steve. Thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on our website at LOE.org, and check us out sooner rather than later.

[MUSIC: Theme to Shaft, Isaac Hayes]

Related links:

- “Deeper Ties to Corporate Cash for Doubtful Climate Researcher”

- "Documents Reveal Fossil Fuel Fingerprints on Contrarian Climate Research"

- “At last, proof of a climate scientist getting rich peddling science.”

- The Weeks Act

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, James Curwood, and Jennifer Marquis. Our show was engineered by Tom Tiger, with help from Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more; www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth