March 20, 2015

Air Date: March 20, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Oil Train Safety Off Track

View the page for this story

In the past five weeks, there have been 5 oil train derailments resulting in large fireballs, and more oil was spilled in 2014 than in the last 38 years combined. Steve Kretzmann, Director and Founder of Oil Change International, and Sarah Feinberg, Acting Administrator of the Federal Railroad Administration, discuss rail safety with host Steve Curwood and offer different solutions to this multifaceted problem. (11:40)

Conservationists Help Workers Strike for Refinery Safety

View the page for this story

The United Steelworkers Union, representing oil refinery workers, reached an agreement with Shell Oil, ending a strike primarily about workplace safety. Joe Uehlein of the Labor For Sustainability Network tells host Steve Curwood why some environmental organizations joined the picket line in solidarity. (07:35)

One Woman Fought Shell Oil To Save Her Town

/ Reid FrazierView the page for this story

Norco, Louisiana is named after the New Orleans Refinery Company, which built a highly polluting refinery there in the early 20th century. The Allegheny Front’s Reid Frazier tells the story of Norco resident Margie Richard, who went all the way to the UN to protect her town’s public health. (08:00)

The Place Where You Live: Omaha, Nebraska

/ Patrick MainelliView the page for this story

In his essay for Orion Magazine, Patrick Mainelli, a writer and community college professor in Nebraska, describes his morning commute through the wilds of urban Omaha. (05:00)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about a global flatline in carbon emissions for 2014, increases in climate coverage by the media, and how beavers have flourished since the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone. (04:30)

How Beavers Help Save Water

View the page for this story

In the drought-ridden West, some people are partnering with beavers to restore watersheds, where, before trappers arrived, the large rodents once numbered in the millions. Film-maker Sarah Koenigsberg captures various efforts to reintroduce beavers to their former habitat in her documentary The Beaver Believers and tells host Steve Curwood why beavers are essential for a healthy ecosystem. (11:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Steve Kretzmann, Sarah Feinberg, Joe Uehlein, Patrick Mainelli, Sarah Koenigsberg

REPORTERS: Reid Frazier, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The six-week refinery workers strike saw environmental advocates and labor on the picket lines together, making common cause for better safety conditions and the transition away from fossil fuels.

UELHEIN: Even in an era where we know we have to dramatically reduce carbon emissions quickly, no worker, no coal miner, no fossil fuel worker should be the road kill along that path.

CURWOOD: A call for fair play for workers caught in the winds of climate change. Also how one woman’s fight for clean air got a whole town resettled.

And another visit to the place where you live – Omaha, Nebraska.

MAINELLI: “How nice,” we say here, and then returning to our work in the corn and soy and parking lot fields of Eastern Nebraska, go about our day.

CURWOOD: We’ll have that and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

Oil Train Safety Off Track

Five oil train derailments in five weeks--some with dangerous fiery consequences. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. At 12 million barrels a day, the US is the world’s leading oil producer, with much of the boost due to fracking technology. With pipelines at capacity the boom has led a 4,000 percent increase in the volume of crude oil that travels by rail, and that brought more accidents and more oil spills in 2014 than over the previous 38 years. Just these past five weeks brought five more derailments, with huge fires and polluted waterways, and some critics say new rail safety rules on the drawing boards won’t go far enough to protect the public or the environment. Steve Kretzmann is Executive Director and Founder of Oil Change International. Welcome to Living on Earth, Steve.

KRETZMANN: Thanks so much for having me here, Steve. It's great to be back.

CURWOOD: Now, what we are seeing is a lot of crashes and explosions. What's happening?

KRETZMANN: So we're seeing, unfortunately, a very visible result of the ‘all of above’ energy policy, playing out with great risks to our communities around North America on a whole. The Bakken oil is very light oil, and it's very explosive, it turns out, and people have known this, but it hasn't really stopped them from shipping it via rail. And it's also worth noting that because that oil is light oil, that's mixed in with tar sands to form diluted bitumen, which is usually the way tar sands get to market, we're also seeing tar sands trains now explode, and so they're just trying to get as much out as fast as they can and maximize their profit. And as we know, the oil market is flooded with crude now and effectively we're subsidizing that with our safety in our communities and our lives.

CURWOOD: Now, in Texas where there's a fair amount of fracking for oil, there are machines that remove the most volatile portion, the most explosive part of fracked oil before it is shipped, but in North Dakota it is not. Why this discrepancy? Why don't they make this safety precaution in North Dakota?

KRETZMANN: Well, it's about profit, it's about investment and infrastructure by the industry, so the production in Texas is very close to markets and so when they invest in the infrastructure to remove the lighter petroleum product - natural gas among other things - they can then sell that oil because they can put in the pipelines. On the other hand, North Dakota does not have those gas pipelines and the infrastructure is not there to capture it and so their options are burn it or try to force it into the tank car, which is what they're doing. There are new regulations that are supposed to take effect from North Dakota that will reduce the amount that they can squeeze in there on a regular basis, but it's not clear that the regulation is in line with what will actually create a safe car. It's just slightly less than they've been able to get away with.

Older DOT 111 cars usually do not fair well in crashes, even at low speeds. (Photo: Robert Taylor; Flickr Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the new tanker safety rules and how effective they might be in preventing the kind of explosions we've seen on oil train derailments.

KRETZMANN: So it's not clear what the new rules are going to be. There are the North Dakota rules which are a slight reduction in vapor pressure, and then there are the federal rules, which are under consideration by the Obama administration, and we're going to see another draft of those supposedly within the next month. But there are very different options that they can take. They could build thicker-walled oiled trains, they could require that, but the oil industry doesn't like that because it costs them more money. They could install electronically controlled pneumatic brakes on the railcars, but the rail industry doesn't like that because it costs them too much money. One of the most effective things they could do is introduce a very serious speed limit. The DOT 111s, the old cars, still make up the majority of the crude by rail fleet; they've been shown to explode at seven miles an hour. The 1232s, which are the newer supposedly safer cars, but are the ones that have been involved in each one of these accidents recently, have been shown to explode at 15 miles an hour. So, we say you should put in serious restrictions here: all new cars, speed limits at 15 or below, particularly in populated areas. You know the industry gets very upset about that and says, “oh my God, that would mean we would have to stop production”. And you know, the point is “yes”, maybe actually reducing some production in the name of public safety is worth it here.

Steve Kretzmann is the Founder and Executive Director of Oil Change International. (Photo: courtesy of Mr. Kretzmann)

CURWOOD: So you mentioned that communities are at risk from these crude oil trains. What ones come to mind for you?

KRETZMANN: So when you look at the map of where crude oil trains are going around the United States, it's very clear you start looking at the routes: Minneapolis, Chicago, St. Louis, New York, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Detroit. All these cities have crude by rail trains, these bomb trains running right through them. 25 million Americans live within the blast zone here and it's sadly not a question of if but when one of these explosions is going to result in a tremendous tragedy. We have the opportunity to slow this down and put a moratorium in place before this happens and we should take it.

CURWOOD: That was Steve Kretzmann of Oil Change International. Well, a moratorium on oil transport by rail is unlikely, and the Obama Administration has yet to issue new rules, even after two years of work. So in the face of the recent accidents it’s issued some emergency rules and here to explain is Sarah Feinberg the Acting Administrator for the Federal Railroad Administration. Welcome to the program.

FEINBERG: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So what do you have in place now in terms of emergency regulations then, emergency rules?

FEINBERG: Well, we have a lot. We have a requirement of railroads to share information about the product that's being transported with emergency responders in each state. We have an emergency order that's in place regarding testing and making sure that the right tank car and right packaging is being used for each product. Over the course of a year and a half that I've worked on this issue, we were enforcing against violations for not testing the product properly, not packing it in the right container, not handling it the right way, not sharing information about it. I'm not saying things are in a good place now, they certainly aren't. We've got a long way to go, but when I think back to where we were a year and a half ago, it's amazing to me we're actually having a conversation about testing then.

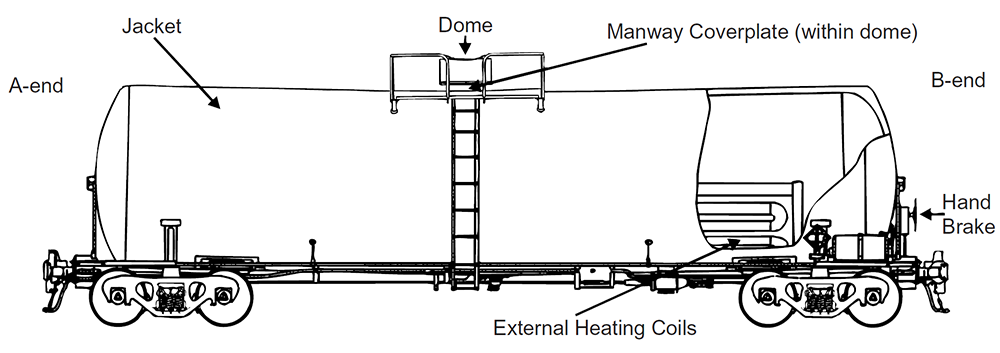

A DOT-111 tank car with an insulating jacket and external heating coils can hold 20,000 gallons of crude. (Photo: National Transportation Safety Board; Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Now, not long ago there was a dramatic explosive derailment in West Virginia that involved the new kinds of cars, the supposedly safer cars, and some folks are saying that apparently having those cars aren't safe enough. What you say?

FEINBERG: Well, it's really important to understand the different kinds of cars that are out there. The one we hear about a lot is the DOT 111. That is the older tank car; I think everyone agrees across the board that tank car is certainly outdated. It's not safe enough to hold this product or others. Industry on its own a few years ago came up with their own version of a tank car that's called the 1232. While it is a better tank car, and it's a newer version of a tank car, one person on my team once referred to the 1232 as the .111 with a five-mile per hour bumper on it. So it's a Pinto with a better bumper instead of just a Pinto. The other most important thing to think about is that all 1232s are not the same. They didn't have all the safety components that they could have had. They didn't have a jacket; they didn't have a thermal shield. These are important components to keep a tank car from basically experiencing the thermal events that create fireballs.

CURWOOD: No matter what kind of car it is, they're going off the rails. Some folks say that the trains are just simply traveling too fast.

FEINBERG: Look, I mean speed should be a factor, but the reality of is that in all of these derailments, they've been very low speed. In fact, the agreements that we have in place with the railroads limit speed at 40 miles an hour. We're now in a position where we've got railroads functioning below the maximum speed and we are still running into problems. There is not a tank car at this moment or even the new version of the tank car we've proposed that will survive a derailment above, say, 16 or 18 miles an hour. So that's one of the reasons why this issue is so complicated. There is literally not a silver bullet. It's not speed, it's not a particular tank car, its not the way the train is operated. It's all of the above and it needs to include, frankly, the product itself that's being placed in the transport, the product that's leaving the Bakken and heading to the refinery.

CURWOOD: How safe is it to allow such volatile fuel to be transported on rails?

Sarah Feinberg is the Acting Administrator of the Federal Railroad Administration. (Photo: FRA)

FEINBERG: I mean, if I have to be honest, I would prefer that none of this stuff be traveling by rail. I worry a lot about not just the folks who are working on the train and the passengers on the Amtrak that the train is going by, but I worry a lot about the people living in the towns and working in the towns that these trains are going through. Now, we have some routing protocols in place. There is a whole software system that the railroads use when they are trying to determine the right route for a substance like this, so it looks at things like city size, it looks at possible defects on rail, it looks at weather, it looks at speed, it looks at traffic, it looks at all of those factors and it basically spits out the best route for you to take.

CURWOOD: Industry a few days ago went over to the Office of Management and Budget, the folks who review the rule-making there inside of the OMB, and made a lot of complaints about the proposal to have this updated form of braking, they say it won't have more significant safety benefits, it won't have much in the way of business benefits and be extremely costly. Sounds like industry is pushing back against getting this stuff under control. Your take?

FEINBERG: Yeah, sure. And I expect that. Look, OMB meets with industry, yet the FRA is required to meet with all interested parties as well. So, as many meetings as I did with industry, I think we all did with the environmental community, small-town mayors, governors and interested members of Congress. So there are a whole lot of folks with a dog in this fight and they all want to talk to the regulator and they all want to talk to the Office of Management and Budget to affect the outcome of the rule. I think at the end of the day it's OMB's job and it's FRA's job to come up with the best possible rule that we can that will actually address the challenge. To be clear, that's not an easy thing to do right now. It's a bit amazing at this point you can take a common sense safety measure and watch the amount of time that it can actually take to turn into a regulation, but you know that's my frustration, that's our problem and our issue to deal with, and the main thing is we should just be keeping people safe.

CURWOOD: Sarah Feinberg is the Acting Administrator for the Federal Railroad Administration. Thanks so much for taking the time today.

FEINBERG: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: We asked the Association of American Railroads for comment on the proposed new regulations.

Spokesman Ed Greenberg’s reply is posted in full at our website, LOE.org.

It reads, in part: “America’s rail industry believes final regulations on new tank car standards by the federal government would provide certainty for the freight rail industry and shippers and chart a new course in the safe movement of crude oil by rail.”

Coming up...the power of labor allied with environmental activists. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

The Association of American Railroads comment:

“The safety of the nation’s 140,000-mile system is a priority of every railroad that moves the country's economy and the freight rail industry shares the public's concern over recent high-profile incidents involving crude oil. This is a complex issue and a shared responsibility with freight railroads and oil shippers, which are responsible for properly classifying tank car contents, working together at further advancing the safe movement of this product.

The fact is, safety is built into every aspect of the freight rail industry, it is embedded through-out train operations and a 24/7 focus for thousands of men & women railroaders. Billions of private dollars are spent on maintaining and modernizing the freight rail system in this country. Since 1980, $575 billion has been spent on safety enhancing rail infrastructure and equipment with another $29 billion, or $80 million a day, planned for 2015.

Railroads have done top-to-bottom operational reviews and voluntarily took a number of steps to further improve the safety of moving crude oil by rail. Actions have included implementing lower speeds, increasing track inspections and track-side safety technology, as well as stepping up outreach and training for first responders in communities along America's rail network.

Federal statistics show rail safety has dramatically improved over the last several decades with 2014 being the safest year in the history of the rail industry. More than 2 million trains move across our country every year hauling everything Americans want in their personal and business lives with 99.995 percent of cars containing crude oil arriving safely. That said, the freight rail industry recognizes more has to be done to make rail transportation even safer.

Freight railroads do not own or manufacture the tank cars carrying crude oil. Still, the freight rail system has long advocated for tougher federal tank car rules and believe that every tank car moving crude oil today should be phased out or built to a higher standard. We support an aggressive tank car retrofit or replacement program.

America’s rail industry believes final regulations on new tank car standards by the federal government would provide certainty for the freight rail industry and shippers and chart a new course in the safe movement of crude oil by rail.”

Related links:

- Interactive Map: North American Crude by Rail

- “Yet Another Oil Train Disaster”

- “U.S. DOT Announces Comprehensive Proposed Rulemaking for the Safe Transportation of Crude Oil, Flammable Materials”

- “U.S. DOT Takes New Emergency Actions as Part of Comprehensive Strategy to Keep Crude Oil Shipments Safe”

- PHMSA helped FRA prepare the railroad safety proposal to the White House

- “U.S. rail industry pushes White House to ease oil train safety rules”

- More on the DOT 111 cars

- The newer oil tank cars, CPC-1232s, were involved in each of the recent derailments

- The runaway crude train explosion in Lac-Mégantic

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Alberto Mesirca, Farewell to Stromness, British Guitar Music Paladino 2012]

Conservationists Help Workers Strike for Refinery Safety

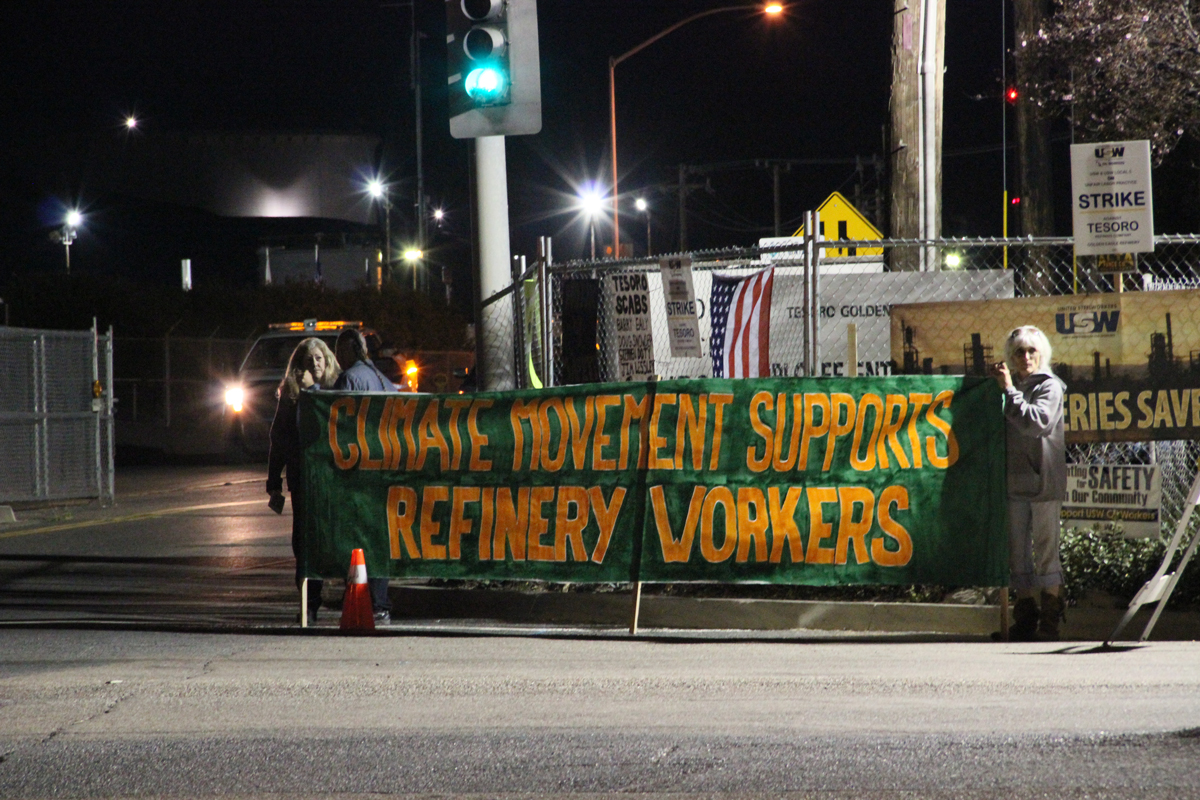

Eco-activists on the union picket line during the refinery workers strike in Texas (Photo: Elizabeth Brossa; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Oil refineries are inherently dangerous places to work – plagued by leaks and explosions – and safety conditions were at the heart of the six-week workers strike that was recently settled with a tentative agreement. The union workers on the picket line also won support from a number of environmental organizations, demonstrating an important alliance between those groups. To discuss these developments, we’re joined now by Joe Uehlein, Executive Director of the Labor Network for Sustainability. Welcome to Living on Earth, Joe.

UEHLEIN: Thanks.

CURWOOD: Now, your organization, the Labor Network for Sustainability, put out a call for environmental organizations to support this strike. Why did you do that?

UEHLEIN: Well, we did it because historically the big Shell strike in 1973 was a turning point in labor environmental engagement. We had just had Earth Day...1970 I think was the first Earth Day, and then '73 this big strike hits in the oil industry and there was a lot of support from the environment groups. They won the strike but then there was also this deeper level of engagement between labor and environmental movements, so whenever these kind of things happen in this case it was clear cut and we came out quickly with a call for support because we need to continue to deepen those relationships, especially in an era of really runaway global warming and climate change which no one was thinking about in 1973.

Steelworkers protest for safe refineries in downtown Houston. (Photo: Elizabeth Brossa; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now which organizations, which environmental organizations responded to the call this time?

UEHLEIN: Well, Oil Change International, Friends of the Earth, and the Sierra Club, they were all right there real quick with really good statements. Bill McKibben from 350.org, he was right there with a great statement, and there were others. Both local environmental groups in the areas where these refineries are, as well as statewide and national organizations.

CURWOOD: Even with this history we don't often hear stories about collaboration between labor and environmental communities. For example, in Appalachia you have the United Mine Workers union very concerned about the carbon regulation, environmental regulation, and a number of environmental groups who aren’t very interested in protecting coal-mining jobs. So, a history of tension here.

Workers march through Houston. (Photo: Elizabeth Brossa; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

UEHLEIN: Yeah. Even in an era where we know we have to have dramatically reduce carbon emissions quickly, no worker, no coal miner, no fossil fuel worker should be the roadkill along that path. We should be fighting for just transition programs and strategies to provide for those workers and communities that might be hurt by a transition to a clean renewable energy regime, and we're only going to win those if labor and environmentalists fight together for that, so we're always working with environmental organizations to get past what I call their well-earned reputation of being insensitive to working people's concerns, and you get past that by really trying to understand the primacy of work in people's lives – understanding it, honoring it, and then fighting to protect those who are going to be damaged by these transitions. We've seen it with globalization and the loss of our industrial base where tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of workers who had good paying jobs in major industry with healthcare and pensions lost it all. We need to change that past paradigm and provide a real sort of a G.I. Bill of Rights kind of program for working people and help them transition into something different. It doesn't have to be that they transition to renewable energy, it might be that, but the transition can be into other industries, they just have to be good ones that pay family supporting jobs. That's the fight and that's the linkage between environmental and climate activism and addressing income equality.

“Safe Refineries Save Lives” (Photo: Elizabeth Brossa; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So what are you guys doing to try to bring labor and the environmental movement closer together?

UEHLEIN: We're doing a lot. We talk a lot about all the industries that are in transition and how to do that in a just way. We're always talking to labor people about the importance of understanding the climate crisis and the impact it's going to have on labor. Climate change is the real job killer. If we don't address it, a lot of jobs are going to be lost.

CURWOOD: What are the jobs are going to be lost by climate change?

UEHLEIN: Well, think about in Maryland, we have thousands of miles of coastline, and the ports, those jobs are going to be lost. The agriculture in the southern part of the state, which is all very low-lying land, that's going to be lost. Most of our major airports are at sea level. They're all going to be impacted, all the roads to and from the ports, that's going to get shut down with more intense storms, more frequency of storms, and just rising sea level itself. So the job loss is going to be immense even as temperatures rise, productivity goes down in construction across the board. So on the flip side then, we're working on a study right now of how to create climate friendly jobs quickly and I say quickly because this study will not only identify the clean energy jobs - it will do that...solar, wind, geothermal and others - but we also have to create jobs that are like shovel ready now and put people to work and that gets to the other industries that are in transition that we need to be focusing on.

Environmentalists support the refinery worker strike at the Tesoro Refinery in Concord, California. (Photo: Peg Hunter; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: For example?

UEHLEIN: Well, for example agriculture and food. We live in a country with one of the most abundant food supplies on the planet, and it's hard to imagine a country that could mismanage it worse than we have. It all needs to be redone. Our whole way of agriculture and supplying food is in transition now and has been for a decade. If we think about Kentucky's history, hemp used to be the largest agricultural crop in the state. We're living in an era of legalization of the cannabis plant, which includes hemp. Let's get it back in there in Kentucky, and let's start to produce and put those miners to work with and hemp and hemp-related products.

Joe Uehline (Photo: Labor Network for Sustainability)

Think broadly is the point. Education. If you've got kids in school you know that if the class size is 25 you're lucky. There should be 10 kids in class. We should employ twice the number of teachers and pay them more and we can do it. What the opponents always say is we can't afford it. We could put solar panels on every residence in the United States for the cost of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. We have the money. We just need to redirect it and put our minds to using it in a better way.

CURWOOD: Joe Uehlein, Executive director of the Labor Network for Sustainability. Thanks for joining us, Joe.

UEHLEIN: My pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Related link:

Labor Network for Sustainability

One Woman Fought Shell Oil To Save Her Town

Margie Richard stands in what used to be her front yard, across the street from Shell's Norco, La. chemical plant. Richard pushed for the company to buy out the neighborhood and move residents. (Photo: Reid Frazier)

CURWOOD: Well, one town on the frontlines of the oil workers strike was Norco, Louisiana - home to a refinery and a Shell chemical plant. Pollution and safety concerns are hardly breaking news in Norco. Forty years ago, residents were complaining about fumes from the plant, and health problems, and eventually many residents were relocated, largely thanks to the efforts of a retired schoolteacher. But such worries aren’t obsolete. Shell plans a new chemical plant in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, to make plastics using the copious local supply of Marcellus shale oil. And as Reid Frazier of the Pennsylvania public radio program the Allegheny Front reports, the determination of one woman in Norco years ago has lessons for residents of Beaver County today.

FRAZIER: Margie Richard is walking on a street with no houses anymore, just lawns.

RICHARD: That’s the backyard of my mom and dad’s house, which was right there, and my mobile home, which was over here.

Looking out on the Mississippi River from Norco. Louisiana's Chemical Corridor, a 100-mile stretch of more than 100 chemical plants with about 27,000 jobs, provide about a quarter of the nation's petrochemicals. (Photo: Reid Frazier)

FRAZIER: This is Norco, Louisiana. We are about 300 yards from the Mississippi River, 20 miles or so upriver from New Orleans. Richard is a 71-year-old former schoolteacher. She points to a tree where her mom used to sit.

RICHARD: She liked to sit outside. But it got to the point she couldn’t sit outside because the fumes was always gas—she had to go inside.

FRAZIER: The fumes she’s talking about were coming from a petrochemical plant owned by Shell a few feet away.

Shell built a refinery here in 1916. The New Orleans Refining Company, or NORCO, ran the facility and eventually, the town adopted the name.

In the 1950s, Shell built a chemical plant nearby in an all-black part of Norco called Diamond. Richard grew up next to the plant. But years later, she would lead a fight to have the company relocate the neighborhood.

As a child, she grew up smelling foul odors from the plant that she likened to bleach. She remembers people in the town suffered health problems, which she blamed on those fumes.

RICHARD: Everybody within these two streets had breathing machines in their house.

FRAZIER: Then one day in 1973, a teenager named Leroy Jones started a lawnmower a few feet from a leaking pipeline, sparking an explosion. It killed an elderly woman who lived nearby. Her name was Helen Washington. Richard remembers the scene vividly.

RICHARD: There on the ground was Miss Helen who lived in the house, under a sheet. And you could smell her hair—it was just awful.

FRAZIER: This was a turning point both for the town and for Richard. She began taking stock of the health problems experienced by people in her neighborhood. Her sister contracted a rare inflammatory disease called sarcoidosis. But the symptoms were so common, her sister didn’t realize she had it until it was too late.

Margie Richard with a photo of her sister Naomi, who died at the age of 43 from a rare bacterial infection. Richard suspected emissions from Shell had something to do with making her sister sick. (Photo: Reid Frazier)

RICHARD: It’s like an allergy, you think you got sinus or whatever...certain times of the year – seasonal change.

FRAZIER: Though there’s disagreement over what causes the rare disease her sister had, some scientists think chemical exposures can trigger it. Richard suspects that was the case for her sister Naomi, who died at the age of 43.

In 1988, there was another explosion. This time it was at Shell’s oil refinery in Norco. The blast killed seven workers and damaged walls and buildings around the town. It was so strong it set off alarms in New Orleans, 25 miles away.

Richard decided to fight Shell, to get the company to relocate residents away from both plants. Richard helped bring in an environmental group that monitored air emissions with 5 gallon buckets.

RICHARD: We learned how to capture the air, how to have statistical reports.

FRAZIER: The group detected chemicals in the air that Shell had never reported to the state’s environmental agency. This caught the attention of the press, and regulators. Before long, Richard was being asked to share her findings. She spoke before the UN in the Netherlands, where she confronted a high-ranking Shell executive. She remembers the meeting, in which she brought a sample of air taken from Norco:

RICHARD: I stood before the United Nations, with my bag of polluted air

FRAZIER: And she asked the executive, would he like to breathe the air?

The gambit worked. A few weeks later, another executive from Shell knocked on the door of her trailer in Norco, wanting to talk. Soon, the company was offering to buy people’s houses near the chemical plant with a minimum offer of $80,000. More than 300 families took the buyout, including Richard’s.

Throughout the campaign Shell denied that its plant made people in Norco sick. And though it’s the subject of much debate, there’s no scientific proof that Louisiana's chemical industry has anything to do with the state’s high incidence of cancer - according to the CDC, Louisiana has the second highest cancer rate in the country. A Shell spokeswoman says the decision to buy out homes was in no way related to health concerns, but part of a longer-term effort to create a greenbelt around the chemical plant.

Lionel Brown chose to stay in Norco. He works at a Dow chemical plant and said emissions are lower than before. (Photo: Reid Frazier)

Still, even industry backers say big chemical plants in Louisiana are better neighbors these days than they were a generation ago, when Richard was fighting Shell.

JOHNSON: The industry recognized that it had to do a better job communicating with and listening to the citizens who lived in communities around them.

FRAZIER: Tim Johnson is a public affairs consultant to the petrochemical industry in Louisiana. He says experiences like Norco’s have been part of an evolution the industry has undergone in the past 25 years. Part of this had to do with companies simply wanting to do the right thing. But, he even admits, part of it was because they were forced to.

JOHNSON: You have to be honest to say …that a lot of the improvements they’ve made have been as a result of regulations.

FRAZIER: These improvements have cut toxic air releases in Louisiana by about half of what they were in the early 1990's.

The EPA now has a program to ensure black and other minority neighborhoods – like the Diamond section in Norco -- aren’t subjected to inordinate amounts of industrial pollution.

Ted Davis, a World War II vet and retired Shell Norco employee said the fumes and the smell of chemical production were part of the job. (Photo: Reid Frazier)

Today Diamond, the neighborhood where Margie Richard grew up, is quiet, except for the hum of Shell’s chemical plant. About 40 families stayed here. They received a home improvement grant from Shell. One who stayed behind is Lionel Brown. On a Saturday afternoon, Brown tinkers with his brother’s pickup truck in his driveway.

[BROWN’S DRIVEWAY]

BROWN: I saw no reason to move—I didn’t want to sell—first of all they didn’t give enough money for what I had.

FRAZIER: What he had was a house and four adjacent lots. Now that air monitors have been installed in the neighborhood, he’s also not so worried about pollution.

Brown works at a nearby chemical plant for Dow. That makes him feel safer about living next to the Shell plant, even though he knows the chemicals made at his job are dangerous.

BROWN: They make stuff that’ll kill you. [LAUGHS] But everything is contained.

FRAZIER: Margie Richard now lives in 15 minutes away from Norco. She thinks community leaders in Pennsylvania need to pay attention to what the company is considering for Beaver County.

RICHARD: You should have input in what is going on.

FRAZIER: She says it took decades, but Richard thinks the town and the company finally learned this lesson.

CURWOOD: That’s Reid Frazier of the Allegheny Front. This story was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Related links:

- Check out the original story on the Allegheny Front website

- And listen to more from Reid Frazier’s series “The Coming Chemical Boom”

- The New Orleans Refining Company (NORCO)

- Richard became involved with the Louisiana Bucket Brigade

[MUSIC: Air, Dirty Trip, The Virgin Suicides, 2000]

The Place Where You Live: Omaha, Nebraska

Winter Nebraska field (Photo: Patrick Mainelli)

CURWOOD: We head off to the Prairie now, for another installment in the occasional Living on Earth/Orion Magazine series “The Place Where You Live.” Orion invites readers to put their homes on the map and submit essays to the magazine’s website, and now we’re giving them a voice.

[MUSIC: Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes “Home” from Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes (Rough Trade Records 2009)]

Your special place doesn’t have to be exotic. It can be ordinary and workaday, but it’s still home.

[MUSIC: "Immigration" From the motion picture soundtrack "Nebraska" by director Alexander Payne and composer Mark Orton. (Milan Records 2013)]

MAINELLI: My name is Patrick Mainelli. I live in Omaha Nebraska. I've lived here for 30 years now. This is farmland and some of this was floodplain years ago. There are some hills and treed areas right along the river, but other than that it gets quite flat very fast. Omaha is a very urban area, so once upon a time there were farmers living around here, but most of them have moved farther west or further north. So people do the same thing in Omaha that they do all in all cities, which is drive to an office and sit in a chair.

Omaha sunset (Photo: Patrick Mainelli)

The essay kind of just chronicles a regular average Wednesday morning for me, which involved waking up decently early, drinking some coffee, regarding the morning and then driving to work. The part of town we live in, we're really attracted to. It's an older, lower-income part of the city, but we like especially that it's just so dynamic and there are so many different people here. Part of the essay captures that because as I drive down a few miles of road to the place where I work, I pass so many different businesses and so many different lives for me offers a kind of wildness to the place, or at least, some sort of dynamic that I can appreciate even though there's little natural things to be seem here.

Here's my essay about Omaha, Nebraska:

It’s Wednesday here, and when the sun comes up its rays lance the stubborn cloud and trace pastels over land so flat and featureless that to follow the light down any road, in any direction, is to find only more and more and more of a world that is inexorably the same. We can call it beautiful though—this lazy play among the groggy hours—just as you are prone to do, seeing the same early light come to fall among the mountains and oceans and prehistoric forests that perhaps you call home. “How nice,” we say here, and then returning to our work in the corn and soy and parking lot fields of Eastern Nebraska, go about our day.

A dusty road (Photo: Patrick Mainelli)

When humans were first humans on the grass plains of Africa, they enjoyed a bareness of land similar to ours here. Today there’s still a very old comfort to be had in waking up among the austerity of grass. We remember. Falling asleep with no trees to interrupt the stars. Moving easily in small bands across the open plain. Standing on hind legs, peeking above the seed heads, spying the lion a mile before she’d crept near enough to draw blood.

Driving to work on Wednesday morning I see—at thirty miles an hour—a few dozen Canada geese trimming a lake that was once the water hazard of a golf course, but is now—following certain economic declines—only a lake. Down Ames Avenue I pass Phil’s Foodway, Jim’s Rib Haven, Doc’s Lounge, YoungBlood’s Barber Shop, Mid-K Beauty Supply, and the rough-hewn faces of churches I will admire but never enter. Although I love these places, and love the fact that humanity has traveled halfway around the globe just to clean the floors and stock the shelves of B.J.’s Gas and Beer, I am lonely for the grass.

A hillside that Patrick Mainelli passes on his way to work in Omaha. (Photo: Patrick Mainelli)

At the community college where I work, I leave my car and pass the now frozen leaves of ancient landscaped trees. Today, just like yesterday before, everything has changed. If only we lived long enough to know the difference.

I think that to some extent we’re all attracted to absences. And when you live in the Midwest you get reminded of absence wherever you look, because the landscape has been changed so much by agriculture and by industry. As far as we know humans are the only animals capable of nostalgia. Sometimes it can feel like a drag to have been born in a time of such change and such depletion, but to some extent this is just a very human way of looking at things. Mountains and mayflies don’t have this problem; we live just long enough apparently.

Some parts of Omaha are still rolling fields. (Photo: Patrick Mainelli)

[MUSIC: "Immigration" From the motion picture soundtrack "Nebraska" by director Alexander Payne and composer Mark Orton. (Milan Records 2013)]

CURWOOD: That’s Patrick Mainelli, from Omaha, Nebraska – and you can tell us about the place where you live if you like. There’s more about Orion Magazine and how to submit your essay at LOE.org.

Coming up...how one of the world’s great natural engineers might help ease the drought in the west -

That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

Related links:

- Read Patrick’s original essay

- More Place Where you Live Essays

- Listen to other writers read their essays

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies, container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Steve Reich, Music for 18 Musicians 11, section 1, Nonesuch 2005]

Beyond the Headlines

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Time to head off to Conyers Georgia to check out the week beyond the headlines. Peter Dykstra with Environmental Health News, ehn dot org and the DailyClimate dot org, has been delving into that world, and he’s on the line now. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve, are you ready for a little good news? Spring’s starting, so we’re going to let hope spring eternally, at least just a little.

CURWOOD: Well, we’re always up for that, particularly after the record-breaking snows here in Boston.

DYKSTRA: Year after year, the amount of carbon we throw into the atmosphere tends to mirror the state of the global economy. Economic downturn, fewer carbon emissions. Economic boom times, carbon goes boom too, accelerating climate change impacts. But according to the International Energy Agency, in 2014 global carbon emissions flat-lined – pretty much the same as 2013, while the economy grew by three percent worldwide.

CURWOOD: Hmmm, so that flies against the conventional wisdom that some people hold, that you can’t protect the climate and grow the economy at the same time. What do you think is happening to cause this?

DYKSTRA: Well, a lot of things, Steve. Renewables like wind and solar still face some challenges, but the longtime predictions for a breakthrough seems finally to be arriving. And energy efficiency is scoring big, quiet victories in both industrialized and developing nations. One year of flatlining does not a trend or a solution make, but it’s a promising step.

CURWOOD: So, fingers crossed.

DYKSTRA: Exactly. On top of a little good news for carbon, I’m seeing good news … from the news. A couple of organizations with global influence are wide-awake on climate change – the Guardian, and the Washington Post. Over in the UK, the longtime editor of the Guardian, Alan Rusbridger, is about to step down, and that of course is time to think about one’s legacy. Rusbridger says he didn’t want to leave without seeing the Guardian go all-out to cover climate change.

CURWOOD: But hasn’t the Guardian always paid a lot of attention to climate and the environment?

In advance of his upcoming departure from the Guardian, longtime editor Alan Rusbridger is directing the publication to treat climate change as the most important story of our time. (Photo: International Journalism Festival; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: They have, but this is different. Alan Rusbridger says that climate is the most important story of our time, and for once, his newspaper - and website — are covering it like it is.

CURWOOD: And what about the Washington Post?

DYKSTRA: Y’know, I lived in Washington for 12 years and the Post was my hometown newspaper and it had a reputation for being very provincial about the Federal government. If you were an environment reporter, you didn’t cover the environment, you covered the EPA. But recently, the Post, under new ownership and new editors, is treating the world like it’s even bigger and rounder than the Capitol Beltway. A new energy and environment page on the website, and a strong, expanded team reporting globally on energy and environment. Even if newspapers are in decline, other news organizations still take their cues from big guys like the Post and the New York Times, and maybe the biggest cue of all came a couple of years ago, when the Post elevated a veteran environment writer, Juliet Eilperin, to the prestigious White House beat, suggesting that covering the environment isn’t a dead-end punishment for up-and-coming journalists.

CURWOOD: Well, some of us seem to enjoy that dead-end punishment, like you and me. And, you know, I've always thought climate was the biggest story – still is. Hey, what do you have from the history file this week?

DYKSTRA: Steve, 20 years ago this week, gray wolves were re-introduced to Yellowstone National Park in what has been described ever since as a classic success story of restoring an ecosystem. In some places, hunters and ranchers don’t like wolves because they can prey on game animals or livestock. But you know what animal likes wolves?

CURWOOD: Uh, let’s see, I’d say “other wolves” but that’s probably not the right answer.

DYKSTRA: No. Beavers.

CURWOOD: Beavers?

DYKSTRA: Beavers. In a place like the protected ecosystem of Yellowstone, wildlife experts say it works like this: wolves are a key predator to elk. No wolves in Yellowstone, the elk thrive, and when they thrive, they eat a lot of waterside vegetation including young willow and cottonwood trees. Beavers also like willow and cottonwood, but the elk outcompete the beavers. Add wolves back into the mix, there are fewer elk, so what do they do with all that surplus vegetation?

CURWOOD: They leave it to beavers.

DYKSTRA: Exactly. So 20 years later, wolves are thriving, elk are in balance, and beavers have come back too. Outside of Yellowstone, where there’s a thriving human population and a commercial stake in elk hunting, wolves aren’t widely popular. The state of Idaho just wrapped up a population control hunt in which nineteen wolves were shot from helicopters, and the legislature just approved $400,000 to do it again in 2016.

CURWOOD: Gee, Peter, after all that hope, thanks for leaving us on a low note. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News – that’s EHN.org – and the Daily Climate.org. Thanks so much, talk to you soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks, we’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE dot org.

Related links:

- Carbon emissions stop growing globally http://thehill.com/policy/energy-environment/235609-carbon-emissions-stop-growing-globally

- ‘Find a new way to tell the story’ – how the Guardian launched its climate change campaign

- The Washington Post’s Energy and Environment section

- Wolves at Yellowstone National Park

- Idaho lawmakers vote to renew wolf-kill program funds

- Idaho lawmakers get and spend money to kill and save wolves

[MUSIC: Randy Waldman, Leave it to Beaver, Unreel, Concord Records, 2001]

How Beavers Help Save Water

The Beaver Believers live-trapped a beaver family including this kit in Aurora, CO, and relocated them into the forest on a private ranch. (Photo courtesy of Sarah Koenigsberg)

CURWOOD: Well, if we were to leave it to beavers – some of the effects could be downright breathtaking. Out in the American West, beavers once numbered in the millions, before European fur trappers arrived. But by the end of the 19th century the beaver and their dams were all but gone, allowing the west to be won by farmers and ranchers. Now in places the beaver are being restored to their rightful habitat, and helping to restore watersheds in the drought-ridden West. Sarah Koenigsberg, a Washington-based filmmaker, has documented the efforts and successes of half a dozen “Beaver Believers”, who are working hard to bring the big tailed and bucktoothed rodents back. She took time from editing her video to talk about them.

KOENIGSBERG: Well, in our film "The Beaver Believers" we feature the stories of a biologist, a hydrologist, a botanist, and activist, a psychologist and a hairdresser. So these are all very different people who share the common passion of restoring beaver to the west. Some work within the federal agencies, the forest service, others are just average citizens who stumbled upon to the cause accidentally and have found a fulfilling life doing something that they believe in.

The Beaver Believers logo (Photo courtesy of Sarah Koenigsberg)

CURWOOD: You have a person who says she's a hairdresser and she says oh she's not any kind outdoorsy in person but yet she's out there live trapping and relocating beaver and saying that this is the most exciting and satisfying thing she's ever done.

KOENIGSBERG: Yup, that's Sherry Tippee. She is a hairdresser in Colorado, and it's true, her nails are done, her hair's done, she's got perfect makeup on when she comes to do her interview or give a speech but when it's beaver trapping time, she is waist deep in murky muddy messy water, she's slogging around and she's just picking the beavers up and cuddling them and loving on them and sharing the good work that they do.

She stumbled upon beaver totally by accident. She started out just as an animal lover. She heard of some beavers that were going to be killed simply because they were in an urban environment and she thought that was wrong, so she decided to do something about it. She's now the leading live trapper in all of Colorado. I think what she shows us is we don't need to have these rigid boundaries of outdoorsy person or environmentalist. We can all find a cause and get active on it.

CURWOOD: Why did you decide to make this film?

The Beaver Believers Kickstarter Trailer from Tensegrity Productions on Vimeo.

KOENIGSBERG: Well, in my own work I've been looking for new climate change narratives, ways that we can relate to it and actually feel like we are accomplishing something. Most of the climate change narratives that we hear about are very apocalyptic. You have these huge doom and gloom stories, and it seems like there's very little we can do as individuals. So what struck me with all of these beaver believers is that they are working on the problem of water, which is one of the biggest problems of climate change, but is very tangible. They're working at the level of their own watershed. And while they do work very hard, they're finding great joy and satisfaction in this work. So they're almost seeing climate change as an opportunity to act, to get involved, to fix problems we've actually had in our watersheds for several decades now. That just struck me is exactly the kind of inspiring climate change story that we really need to be telling.

CURWOOD: Now, there's a finite supply of water in the drought-ridden American west. Beaver can't increase that water supply. What can Beaver do to help the water situation?

A wildlife biologist assesses a dam on Paneum Creek, WA, for reestablished beavers. He measured the height, width, and amount of water storage that the beavers create. (Photo: Basin Project, Mid-Columbia Fisheries)

KOENIGSBERG: Yeah, you're correct. Beavers certainly don't make more water, but what they do is they redistribute the water that does fall down onto the landscape, so if you picture spring floods - all that water that comes rushing down in March or April just goes straight through the channels and out to the ocean - what beavers do is they almost act like another snowpack reserve, whether it's rain or snow runoff, all of that water can slow way down behind a beaver pond and then it slowly starts to sink into the ground. It stretches outward making a big recharge of the aquifer and then that water ever so slowly seeps back into the stream throughout the rest of the spring and summer as it's needed so that we end up with water in our stream systems in July and August when there is no longer rainfall in much of the west and when it's incredibly hot and our streams are beginning to run dry.

CURWOOD: I want a bit of a backstory here. When settlers arrived in North America a few hundred years ago there were well, zillions of beaver. What happened?

Beaver footprint in new mud. (Photo: courtesy of Sarah Koenigsberg)

KOENIGSBERG: Well, basically, well as the West was being developed there was a race to establish territory and beaver pelts were the currency at the time. So people began to realize if they turned it into a fur desert, if they eradicated every single beaver they would be removing the value in that land so people can come in and claim their stake. Unknowingly they begin to cause great ecological harm. There actually are records in some trapper's journals towards the end of that trapping heyday where they began to realize the mistake that they'd made as they did start to watch stream ecosystems start to crumble.

CURWOOD: So people were trying to eradicate the beaver, didn't quite happen, although I gather in the 1950s the Army Corps of Engineers was supposed to in fact completely finish off the beaver.

KOENIGSBERG: There was another campaign as we came in with our slightly off-kilter logic that the best thing to do would be to get the water from the mountains downstream to reservoirs as quickly as possible. So there was an effort by the Army Corps to straighten a lot of stream channels. That's the exact opposite of what beavers do. They're all about complexity and meanders and letting the water make its way down ever so slowly. So there was another campaign to try to get rid of the beavers, which were only seen as a nuisance to get the water down in the irrigation systems as quickly as possible.

Filming Beaver Believers’ US Forest Service Biologist, Kent Woodruff outside of Twisp, WA. Woodruff’s team relocates beaver to areas where they will help restore waterways and the local flora and fauna. (Photo: courtesy of Sarah Koenigsberg)

CURWOOD: So the landscape has really changed. How do they fit into today's landscape?

KOENIGSBERG: The landscape has changed. We have a lot of incised streams, that means that the bottom has cut down so the stream looks like it's caught in a canyon, and all those areas that means the water table has dropped that low. So when you have these areas with deep incised streams there's no water in that soil until you get all the way down as deep as the bottom of the streambed. So there's not any water for most of the vegetation on top. What beavers can do is even if they start building a dam way down at the bottom, slowly that dam will trap sediment and ever so slowly the bottom of the stream channel will rise back up and then the beavers have to build their dam higher and then it catches more sediment and rises up again. So there's areas where we’ve seen stream channels rise up two, three meters in just a couple of years.

CURWOOD: Beaver evolved side-by-side with other animals and plant life, that ecosystem there. How did this ability of a beaver to slow down the runoff of water affect other species? Salmon for example?

Large beaver lodge in Oregon’s Methow watershed, where beavers were reintroduced three years ago. A low dam across the stream and wetland trapped water in he area, creating a pond. (Photo: NOAA)

KOENIGSBERG: Ah, it's greatly beneficial. As you said, all of those species coevolved and so without the beavers the stream systems have become much more simple and simplicity is not what we want. We want complexity. We want a very rich, biodiverse habitat and suite of species. So with the beavers coming back instead of just a chute of water going straight down the stream, now we have pools and along the edges of the pools there's some really shallow slow-moving areas for amphibians, little froggies and insects, rushing cooler areas as the water comes spilling through the dam. There's a plunge pool at the base of the dam where the water has some force and it's scoured out a little bit of area at the bottom, so you have areas of rapid current, slow current, you have a great variation in temperatures from warm to cool, and it basically creates a much more varied habitat for many, many more animals to live on. There's a phrase "Beavers taught salmon how to jump", and it's quite true. It's amazing you'll see salmon jumping over dams. You'll see littler ones wiggling their way through it, somehow swimming right up through the middle in between the sticks. The dams can provide areas for juvenile fish to rest, they could be off to the side where there's less current, but they could be right at the edge of an area that does have insects so as insects or food sweep by, the fish can more easily stick out their little mouths and grab them. They have areas to hide from predators. Also then there's a lot more vegetation that can grow on the sides, so there's areas the fish can rest in the shade, not warm-up and overheat.

CURWOOD: Sarah, what does it mean to "think like a beaver"?

Two streams near Elko, NV: Trout Creek on the left and Cottonwood Ranch on the right, where beaver live. The ranch owner planned to kill the beavers because, “that’s what you do,” until he noticed that they diverted water into the region. (Photo: courtesy of Sarah Koenigsberg)

KOENIGSBERG: Yes one of the themes in my piece that I really love is called "Thinking like a beaver" and what means to us is learning to discover a way that we can live where we're actually doing good. In beavers keystone role in an ecosystem they're really being quite selfish when they build dams to make ponds. It's for their protection and so they have deep enough water they can hide from predators, they can have an underwater entrance to their lodge, but they are doing something that is very helpful and very good, and I think today we hear so many stories of humans just causing harm and being detrimental in everything we do to nature and the other creatures around us. So I really like this idea of learning to live in a way whereby taking care of ourselves we also take care of the nature around us. I love that we can still stumble upon other species that can surprise us and that we can learn from.

Filmmaker Sarah Koenigsberg is producing “The Beaver Believers.” Sarah holds one of the kits that her crew helped live trap in Aurora, Colorado. (Photo: courtesy of Sarah Koenigsberg)

Beavers are very social. They're monogamous. They're fabulous parents. You can see them teaching their children. They will have little babies on their backs. I've stumbled upon a few areas where you can see some really poor dam building off to the side of the real dam where perhaps the first-year kids were practicing, trying to imitate mom and dad. They're really lovely little critters. They have little personalities and they're very friendly. They're not aggressive or mean. They're a little bit shy. You can tell they'll slap their tail on the water if they get scared, but it's really fun to sneak out to a pond in the evening right before the sun sets and you'll see them come out of the lodge and start to swim around the pond and cut down little branches then POOF they slap down on the water and I almost drop my camera and they dive under, and hide out for a while.

CURWOOD: Sarah Koenigsberg and her team are producing the "Beaver Believers", it's a documentary about the work of six people to reestablish beaver in the American west, and we expect this film to be out sometime in 2015. Sarah, thanks so much.

KOENIGSBERG: Thank you.

Related links:

- “The Beaver Believers” website includes a trailer for the documentary.

- Beaver Believer, Kent Woodruff is a wildlife biologist in Washington.

- “Leave It to Beavers: Can they help us adapt to climate change?”

- PBS’s Nature documents the lives of beavers and how they restore water to dry areas.

- Beavers save a salmon population in California

- Video of the Methow Beaver Project, a effort to improve water storage in some of Washington’s creeks in the face of diminishing snowpack.

- “Ruining” the Rivers in the Snake Country: The Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fur Desert Policy

[MUSIC: Randy Waldman, Leave it to Beaver, Unreel, Concord Records, 2001]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, James Curwood, and Jennifer Marquis. Our show was engineered by Tom Tiger, with help from Jake Rego Noel Flatt and John Jessoe. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth