September 11, 2015

Air Date: September 11, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Undoing Deregulation to Keep Coal Alive

View the page for this story

Natural gas and renewable energy are out-competing coal and nuclear but an Ohio-based power company isn’t ready to give up. Bloomberg Businessweek senior writer Paul Barrett tells host Steve Curwood about FirstEnergy’s efforts to get regulators to force customers to subsidize its aging coal and nuclear power plants and how deregulation — once favored by FirstEnergy — now threatens the company's survival. (06:30)

Beyond the Headlines

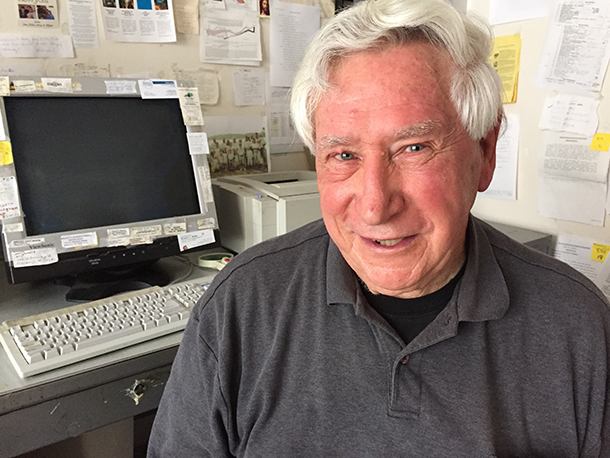

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about FOIA revelations on GMO and organic research funding, the li¬fting of the evacuation order for a town near Fukushima, and a moment in history when nuclear energy seemed likely to mushroom. (04:25)

Global Warming Linked to Syrian Refugee Crisis

View the page for this story

As refugees from the civil war in Syria pour into Europe, we take a look at the role climate change is playing in that crisis as well as the exodus from North Africa across the Mediterranean. Host Steve Curwood speaks with Marc Levy, deputy director of the Center for International Earth Science Information Network at Columbia University about the current refugee crisis and the future of climate-related conflicts and migrations. (14:15)

Fighting Today's Invaders In Boston Harbor

/ Olivia PowersView the page for this story

Boston’s Harbor Islands offer a scenic retreat from the bustle of the city, but they’re vulnerable to inundation by invasive plant species. Living on Earth’s Olivia Powers visited Grape Island on a “Stewardship Saturday” to watch volunteers both young and old help root out invasive buckthorn and other alien plants. (07:10)

A Prayer to Share Earth as a Commons

View the page for this story

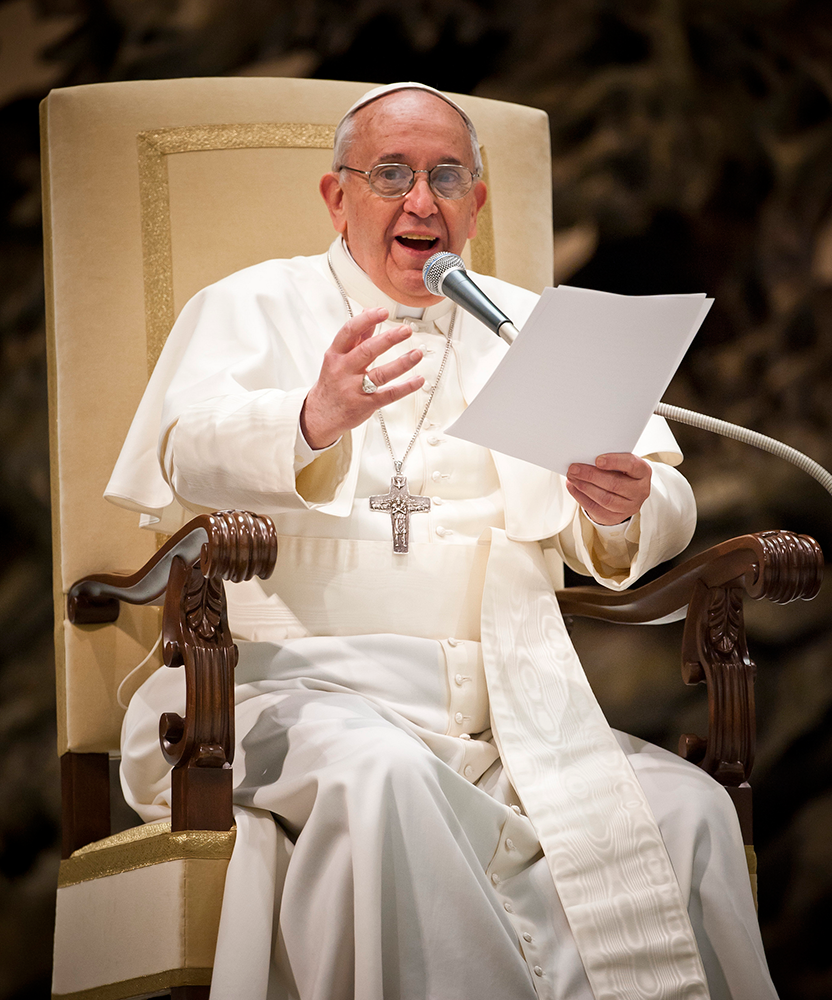

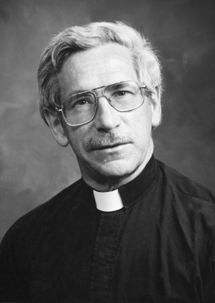

Jesuit Priest Albert Fritsch has long called for “Earth Healing” through his website and work with advocacy groups in both Washington DC and rural Kentucky. Now, Father Fritsch speaks with host Steve Curwood about how he’s using his chemistry background to lead his parish in discussions about Pope Francis’s environmental encyclical, emphasizing the moral and religious relevance of protecting the Earth’s resources for all people. (14:45)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Paul Barrett, Albert Fritsch, Mark Levy

REPORTERS: Olivia Powers, Peter Dykstra

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Refugees are flooding across the Mediterranean and up through the Baltics, driven by drought and civil war, linked to global warming.

LEVY: Whether or not the Mediterranean crisis is a harbinger of more generalized global insecurity triggered by climate change is a question that we have an ability to shape the answer to. The security consequences of climate stress are always preventable.

CURWOOD: Also, 240 years after the Boston Tea Party, today’s volunteers head out to the Harbor Islands to fight plant invaders.

ALBERT: We end up with sort of the same mix of invasive species here in the Boston Harbor Islands that you might find in a park outside of Philadelphia or even further to the west and south of here.

CURWOOD: We’ll have those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable, place to live.

[THEME]

Undoing Deregulation to Keep Coal Alive

Construction of new pollution control equipment on FirstEnergy’s W.H. Sammis Power Plant in Stratton, Ohio. Under the power purchase agreement, three of FirstEnergy’s utilities would be required to buy all the power from this and 3 other coal plants for the next 15 years. (Photo: Sidi762, Flickr Public Domain)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. A major test case is underway in Ohio where a utility company is trying to walk back deregulation in an attempt to keep expensive and aging coal and nuclear plants online. FirstEnergy pushed hard for deregulation back in 2008 and got a $6 billion payout from ratepayers to cover stranded assets at the time. Now it wants to be guaranteed revenues from expensive coal and nuclear power generation, a move that critics say could cost consumers billions. The Ohio Public Utilities Commission is expected to rule on the matter by the end of this year. Joining us from his New York City newsroom is Paul Barrett, a senior writer at Bloomberg Businessweek. Welcome to the program.

BARRETT: Glad to be here. Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: Paul, tell us a bit about FirstEnergy. When deregulation came along, how did FirstEnergy come out ahead in terms of getting a subsidy from customers?

BARRETT: It was more a question of the company had substantial holdings in coal-fired generating plants, which in the early 2000s for a significant period of time were by far the cheapest way to generate electricity. So in a deregulated environment you can use that electricity not only to supply your own customers, you can also sell it on the regional grid and make a fine profit. So that's why a company like FirstEnergy was enthusiastic, at least at first, about deregulation.

CURWOOD: Then what happened? I gather things sort of turned upside down.

(Photo: Stepshep, Wikimedia Commons public domain) BARRETT: Sure, well the marketplace is complex. In more recent years, we've had a revolution in terms of supply of low-price and very plentiful natural gas, which has pretty much undercut all other energy sources, and plants that had been generating healthy profit margins are now not economical - in other words they do not compete on the deregulated energy supply grid - and for that reason those plants are threatened with being shut down. CURWOOD: Shutting down plants is one thing. The viability of the whole business is another. FirstEnergy says it's at risk of going out of business. Why? BARRETT: FirstEnergy's argument is really two-fold. One, that coal-fired plants should be preserved and to some degree, updated because they can provide a steady reliable base-load source of energy; you can run coal-fired plants continually, it's not like a solar or wind operation. The second argument is that FirstEnergy says well, natural gas prices won't always be low, in years out in the future and at that point you'll be thanking us for keeping open coal plants, nuclear operations that today may not be economical but tomorrow will be. CURWOOD: So what is it that FirstEnergy is proposing? What's their plan that it wants in order to stay in business and how would that work? BARRETT: They are proposing, and the Ohio Public Service Commission is actively considering right now, a plan that would basically oblige the utilities that FirstEnergy owns to take all of the output from certain coal-fired plants and one large nuclear plant, no matter what the cost. So it is in effect a return to a more traditional regulatory scheme where the public commission says that ratepayers will bear the risk of the fluctuation in the cost, the company will not bear the risk. FirstEnergy defends this by saying you will guarantee the continued operation of these reliable plants and they project out into the future that eventually this will actually make economic sense, whereas critics of the plan say, “wait a second, this is just a subsidy in effect”. And in fact, calculations have been done that say over the 15-year duration of the plant, consumers of electricity might end up subsidizing FirstEnergy to the tune of some $3 billion so it's not an insubstantial sum of money. The Davis-Besse Nuclear Power Station located on Lake Erie has a history of safety problems and violations. (Photo: Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Public Domain) CURWOOD: Wait a second here. It sounds to me like in this case deregulation didn't work and they want to go back to the old days. BARRETT: That is exactly what FirstEnergy is saying. They wouldn't, I don't think, appreciate saying the regulation didn't work because that would suggest that they made bad predictions and were not able to operate in a competitive environment that they once actually advocated themselves, and to look at it from a slightly different perspective, maybe deregulation did work and revealed that coal is not, under current circumstances and possibly future circumstances, the best economical choice. We know it's not the best environmental choice, in fact it almost certainly is the worst environmental choice, and also solar and wind are becoming more cost-efficient pretty steadily over time and therefore if you're an environmentalist you might say, “hey let's let the marketplace steer us to other sources of energy, so that would be a more positive spin to put on this unexpected development with deregulation. CURWOOD: By the way, how is FirstEnergy handling the EPA's new clean power plant rules? BARRETT: They haven't really engaged with that yet and it's not clear at all that Ohio would be able to comply with the new clean power plant proposals if these coal plants are kept open, because really one of the whole motivations of the Clean Power Plant is to create incentives, economic forces that will shut down the coal plants and shift our energy usage over to cleaner sources and sources that don't contribute as much carbon dioxide. There is a tension right now in Ohio, a conflict over whether the state will use government power to move toward cleaner lower carbon energy sources or whether it will seek to postpone for as long as possible a transition to a greater efficiency, use of cleaner energy and ultimately, the shutting down of coal plants. CURWOOD: Paul Barrett is a senior writer at Bloomberg BusinessWeek and he joined us from his newsroom in New York. Paul, thanks for taking the time with us today. BARRETT: My pleasure. Thanks for having me. Related links: The New York Times filed FOIA requests and found that Dr. Kevin Folta of the University of Florida had promised Monsanto “a solid return on the investment” of a $25,000 grant for GMO communications. (Photo: Seanpanderson, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0) CURWOOD: We’ll take a look beyond the headlines now. Peter Dykstra of Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org has the scoop, and joins us on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hello, Peter. DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. A week ago, we talked about a political activist, a climate denier, who uses the Federal Freedom of Information Act to file huge information requests from climate scientists who receive government funding – that’s a case where the good intentions of FOIA can become a nuisance to scientists who’d rather do their research than collect paperwork. But the New York Times filed a blockbuster story, based on what they learned from the Freedom of Information Act about scientists jumping into the political deep end of the debate over genetically modified crops. CURWOOD: Hmmm, GMO science is one of the few things that can get people as worked up as climate science. So what did they find? DYKSTRA: The Times found that that big biotech companies are pouring money into University research programs. That may raise concerns, but it’s certainly not illegal or unethical, but get this: Emails obtained by the Times show some scientists at those universities jumped into the industry’s PR push in a very un-science-ey way. At the center of all this, Dr. Kevin Folta of the University of Florida, who got a $25,000 grant for GMO communications from Monsanto and emailed his thanks, saying the company would “get a solid return on the investment.” That’s not how science funding is supposed to work, Steve. On his blog, Folta said the Times “Cherry-picked” his emails, and that he’s donating the 25 grand to a food pantry. The web has blown up over this from both GMO supporters and opponents, and I suggest you don’t read the comments on Dr. Folta’s blog unless you’re wearing a gas mask. But the story doesn’t end there….. CURWOOD: No? What else? The Japanese government says that residents of Naraha—one of seven towns in the evacuation zone surrounding the Fukushima nuclear plant—can now return to their homes. (Photo: Wizkid, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0) DYKSTRA: The organic foods industry, which lines up against the biotech industry on issues like labeling GMO foods, appeared to have its own captive academic. Charles Benbrook, who was with Washington State University until recently, came into the post from an organic industry-funded advocacy group. But there’s no evidence that “Big Organic” is steering millions of dollars to universities. All in all, it’s a tribute to the value of the Freedom of Information Act as a means to try to keep us all honest. CURWOOD: And, like so many things, there’s still potential for abuse with FOIA as a harassment tool. Let’s hear another tale from beyond the headlines now. DYKSTRA: How about a little good news from Fukushima? Well, it’s kind of, sort of, maybe good news. The evacuation order has been lifted for one of the seven towns nearest the site of the nuclear disaster over four years ago. The Japanese government says radiation levels in Naraha, twelve miles from the Fukushima nuclear complex, are in the safe zone, and they’ve told the town’s residents they can come home. CURWOOD: Well, that’s maybe a little good news in an awful situation. Are the people of Naraha coming back? DYKSTRA: Some of them say they will. But a recent government poll found that 53 percent of the people in the contamination zone say they’re not ready to return – either they’ve found jobs elsewhere, or they’re still wary about the radiation, or both. And about a hundred thousand people live – or used to live – in those other six towns near Fukushima that are still under an evacuation order. CURWOOD: A nuclear story to be continued. What do you have for us on the history calendar for this week? In September 1954, the Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, Lewis Strauss (seen here with President Eisenhower in March of that year) told science journalists that nuclear energy would become “too cheap to meter.” (Photo: Fastfission~commonswiki, Wikimedia Commons CC government work) DYKSTRA: More nuclear. On September 17, 1954, the Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, Lewis Strauss, put some words about nuclear power in a speech that are still causing arguments today. Strauss was a successful businessman and an ardent cheerleader for all things nuclear. Remember that this was the height of the Cold War, the dawn of the Nuclear Age, and people were talking about using atomic bombs to do things like dredging harbors. And Strauss told a conference of science journalists that nuclear energy would become “too cheap to meter.” CURWOOD: Well, last time I checked, Peter, nuclear’s still about 20 percent of the power supply, and utilities still send a bill every month. DYKSTRA: They do indeed. Strauss was a big booster of nuclear fission – which powers plants across the US, not to mention Fukushima when it was operating – but he also was a huge fan of research on nuclear fusion – the Holy Grail for atomic advocates. And there’s still a debate about whether Strauss was talking about fission, fusion, or all of the above. Nuclear fission plants are aging and struggling to compete in the energy marketplace, we still don’t know how to deal with the waste. And sixty-one years after “too cheap to meter” went supercritical, nuclear fusion is still a technological dream. CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News - that’s EHN.org - and the DailyClimate.org. Talk to you next time, Peter! DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot, we’ll talk to you soon. Related links: CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org. [MUSIC: Mongo Santamaria, La Tumba, Ole Ola (Concord Picante 1989)] Syrian women and children at a Budapest train station in Hungary on September 4th, 2015. (Photo: Mstyslav Chernov, CC BY-SA 4.0) CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. As the humanitarian crisis linked to the civil war in Syria unfolds, millions of refugees are stuck in bleak camps in the Middle East, with hundreds of thousands battering at the gates of Europe. Thousands more displaced by drought in Africa are also risking death to find new homes and new lives. President Obama is among those who see links between climate disruption and these disasters. He addressed the Coast Guard Academy in May. OBAMA: (I) understand, climate change did not cause the conflicts we see around the world. Yet what we also know is that severe drought helped to create the instability in Nigeria that was exploited by the terrorist group Boko Haram. It’s now believed that drought and crop failures and high food prices helped fuel the early unrest in Syria, which descended into civil war in the heart of the Middle East. CURWOOD: It's a contentious claim that strikes a chord with Mark Levy, a national security consultant who teaches at Columbia University. I asked him what grade he’d give the President for his statement. LEVY: I would probably give it an A minus. I think to categorically say that we cannot assign causality to climate change for any of the conflicts that we see is a misrepresentation. I think a more accurate portrayal would be that the evidence is now overwhelming that climate change is responsible for a significant amount of the political violence that's taking place around the world, however there's uncertainty about the exact relative magnitude of that contribution in combination with other causes, and there is uncertainty about which of the cases of conflict have an ironclad causal link to climate change. A lot of people have a hard time accepting the fact that our ability to maintain order is dependent in part on the weather. We would like to think that we are more civilized than that and whether or not we start killing and hurting each other doesn't depend on the temperature and the rain, but the scientific evidence is that it does depend in part on those things. A refugee camp in Turkey. (Photo: Fabio Penna, CC-BY-ND 2.0) CURWOOD: Mark Levy says the problems of refugees, violence and global warming form a complicated nexus that have profound impacts on national security. And in his view, the US intelligence agencies woefully underestimated how powerful an effect the changing climate could have on political stability in Syria. LEVY: We have known for some time that the eastern Mediterranean is a region that is at high risk from climate change. In this particular case in the last decade what's happened is you've had a combination of elevated temperatures and lower precipitation and river flow that have combined to destroy crops and kill livestock and make it difficult for cities and villages to get drinking water. These effects compound over time; if you lose a bunch of your crops one year and next year you also lose a bunch or the same thing with livestock, then you push societies closer to critical thresholds where they can get to the point where they feel like they cannot survive where they are and they have to move. And this is what happened in Syria. We had large numbers of people desperate enough that they took up and relocated and this contributed directly to the grievances, the challenges maintaining order, and combined with the virtual complete lack of responsiveness on the part of the government, led many people to feel they have no choice but to rise up against the government. CURWOOD: Mark, obviously the immediate violence of a brutal civil war is the primary driver of people leaving their homes. Of course, they are also economic issues involved, so how fair is it to raise the question of climate change in this context? LEVY: This is a question that gets debated quite a bit. It has applications for how you assign responsibility within the international community because we have a treaty that governs obligations towards refugees fleeing for reasons of political persecution; we don't have treaties in place for people fleeing for economic reasons. The massive exodus from Syria occurred after the regime dramatically escalated the persecution of people who were peacefully protesting, and that led to an escalation towards a civil war. So in the present case, there's no question about the nature of the obligation of the international community has. This is a case of refugees fleeing the circumstances of political violence in which they have a well-founded fear for their lives. That doesn't mean that climate change is off the hook because climate change did play a major role in creating the conditions that made that war more likely. Two Syrian children at a refugee camp in Iraq. (Photo: European Commission DG ECHO, CC BY-ND 2.0) CURWOOD: Now, where else in the world are we seeing climate change forcing migration? What about the Sahel region of Africa for example? LEVY: The question of where climate migration is taking place is a very sensitive topic, but there was a big round of drought and famine in the Sahel in the 70s and 80s. One place that was hit really hard was Mali and it's very clear that you had disruptions to the migration patterns in Mali as a consequence of those droughts, and some of those migrants were nomadic communities that went into Libya and were trained as mercenaries by the Gaddafi regime. Many of those people ended up coming back into Mali in the last decade and were part of the coalition that overthrew the government. If you mismanage climate stress politically and socially you have dangers that could show up in complicated ways and sort of as a boomerang, you know when it finally comes back and hits you, it may be both surprising and catastrophic. CURWOOD: What about right here in the United States? I'm thinking of people getting displaced by storms like Hurricane Katrina? LEVY: Yeah, we know that extreme events - storms, droughts, fires and so on - they displace people, that's one reason that we worry about them. Katrina displaced a lot of people. Superstorm Sandy displaced a lot of people. So within the US, when people do assessments of what does climate change mean for Americans, this effect is a very large one because we have a well established long-standing sense that people should not be forced to leave their homes involuntarily under such circumstances and when they do it's a clear sign of failure. When I was working with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change a few years ago following a decision by the IPCC to take a look at the security implications of climate change, something that they have never done before, I was surprised to discover that some of the clearest cases where climate change is triggering loss of human security right now in ways we can see were within the US, and that was in the Arctic communities that were facing major disruption in their habitats including to the point where you have entire towns facing the need to relocate because the permafrost was thawing and the local environment was becoming uninhabitable. Syrian refugees sleeping on the floor of a railway station in Budapest (Photo: Mstyslav Chernov, CC BY-SA 4.0) CURWOOD: So the science suggests that climate disruption is only going to get more intense in the decades ahead. So what impact will that have on migration and refugee issues do you think? LEVY: Well, in the course of a decade or two we don't actually know what lies ahead. There's natural variation around a long-term trend, and there are global cycles that could put us into a period of more normal climate for a little while. That's a possible future, we can't rule that out, but when you look at the trends over the last 10 years, what I see and when I think many people are experiencing intuitively is the exact opposite of that best case scenario. We seem to be in the middle of the combination of trends that are worse than we ever imagined, and so if those trends continue we are going to be in for really alarming conditions in the next decade. And politically and economically and socially, the trends are also very bad. We have for the first time since 1990 an increase in the number of internal wars going on globally. This uptick started about five years ago and it caught a lot of people by surprise. People had been thinking we were reaping this peace dividend. People like Stephen Pinker were writing books about how we've licked this problem of massive organized political violence and now what we're seeing is that optimism was premature or misplaced and we have the largest number of refugees ever since World War II, over 50 million, the first time we've crossed that threshold, renewed concerns about international warfare with Russia and Ukraine. So the world is looking more dangerous not less dangerous and so if we adopt the metaphor that many people are using of climate as a threat multiplier, then what you got going on is that the baseline that you're multiplying against is also going up, and so then the product is quite scary. Syrian refugees striking on the platform of Budapest Keleti railway station in Hungary on September 4th, 2015. (Photo: Mstyslav Chernov, CC BY-SA 4.0) CURWOOD: Mark, what needs to be done here in United States and around the world to prepare better for increased displacement linked to climate change? LEVY: The acknowledgement that we face a new kind of threat is necessary, but by itself it accomplishes nothing. So what we need to do is start putting in place the processes that will enable us to anticipate these kinds of risks and therefore be able to prepare for those kinds of risks and either prevent them from getting bad, or when they erupt, dampen how badly they can escalate. It requires getting all the agencies of the US government, just to take the US case, working together and it requires connecting all the dots, the agriculture, the economics, the demographics, the climate, the water, the energy and so on. So somebody has to be regularly putting these pieces together and looking for potential danger zones, and then the final key piece which has been dramatically underinvested in, is that we have to do deep dives into places that look like they might be very dangerous, and to do what in the financial world they called stress testing where we imagine an extreme risk and we ask, “how will the society respond?” So in the Syria case what we should've been doing is imagining an unprecedented drought and then thinking through how society would respond, how the Assad regime would respond and where things would go from there, and nobody in any position of authority was either doing that or asking other people to do that. CURWOOD: Mark, to what extent do you see what's happening now in the Mediterranean as a turning point? Marc Levy is deputy director of the Center for International Earth Science Information Network at Columbia University. (Photo: Columbia University) LEVY: I hope it is a turning point. People hoped that the Darfur genocide was going to be a turning point, and it wasn't. We need to acknowledge that something new is happening and that we need to change the way we anticipate and respond to these kinds of problems. Whether or not the Mediterranean crisis is a harbinger of more generalized global insecurity triggered by climate change is a question that we have the ability to shape the answer to. The security consequences of climate stress are always preventable, they are not inevitable. There are certain things that climate change will do that we can't prevent. If the oceans acidify, a lot of the coral will die and there's probably nothing we can do about that, but refugee situations, civil wars, displacement, deprivation...these things are all preventable. This could easily be a turning point in a positive direction in which we knowledge the threat and rise to the occasion or it could be a place where we moved away from peace and prosperity and descended into a period of insecurity and deprivation. CURWOOD: Mark Levy is the Deputy Director of the Center for Earth, Science and Information Network at Columbia University. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today. LEVY: Thank you. Related links: [MUSIC: Luminescent Orchestrii, “La Tarde”, Neptune’s Daughter (Nine Mile Records 2009)] The docks at Grape Island (Photo: Devin Ford; Flickr CC BY 2.0) POWERS: It’s 9 a.m. on a Saturday, but the sun is already hot over the Boston Harbor Islands. A dozen or so volunteers clamber off a boat onto Grape Island. It’s one of the least developed of the harbor islands, with lush vegetation, hiking trails, and campsites, infamously called Tick Island by locals. The park rangers break out heavy-duty cans of bug spray and pass them around as volunteers tuck their pants into their socks. [SOUNDS OF BUG SPRAY] Mark Albert rips out some pepper weed (Photo: Olivia Powers) POWERS: They’re preparing for a full day of hard work with the National Park Service Stewardship Saturday program. ALBERT: The Stewardship Saturday program got started about 10 years ago now. POWERS: That’s Marc Albert, the director of the program. ALBERT: Other park managers and I wanted to offer the public an opportunity to sort of be hands on with helping to take care of the park. POWERS: The program ferries volunteers out to a different island each Saturday to pull up the invasive species that are crowding out native vegetation. ALBERT: There’s a lot of invasive species that have changed the ecosystems in a way that we end up with sort of the same mix of invasive species here in the Boston Harbor Islands that you might find in a park outside of Philadelphia or even further to the west and south of here. POWERS: Albert says that when invasive species move in they threaten ecosystems and destroy biodiversity. And that’s not all that’s lost. ALBERT: Part of what we’re responsible to do in the National Park Service is to preserve the connections to the past, to help tell the stories of people and how they’ve interacted with places overtime. Probably our signature native species here is staghorn sumac. Native Americans utilized staghorn sumac for millennia here in the harbor islands. And without the staghorn sumac being present it’s hard to feel and understand the deep history of this place. Volunteer Bob Walsh rips out invasive buckthorn. (Photo: Olivia Powers) POWERS: Historically, Native Americans soaked the plant’s fuzzy red berries to make a lemon-flavored tea, and dried its leaves to extend their tobacco. Albert says that pulling out the plants that have taken over will help the staghorn sumac return to the islands. ALBERT: On Grape Island in particular we’ve been working on removing invasive species that are threatening some of the wetland habitats there, and some of the species that occur really throughout the park, such as glossy buckthorn, honeysuckle, and multiflora rose. POWERS: Today, the focus on the buckthorn, a viciously persistent shrub with small fruits and dark, oblong leaves. Meg is one of the volunteers. MEG: The easy thing about the buckthorn that we’re pulling today is that the stem is very recognizable. So if you notice the brown stem with the white spots first, then you can double-check the leaves, make sure they’ve got the big veins. And then it’s a matter of tugging on it, trying to find where the root is, and then if you can team up with somebody to try to pull it out and try not to get all of the other plants that are in the area. POWERS: It’s hard work, but rewarding. Here’s volunteer Ray Watkins. WATKINS: The little area that we’re standing in right now, we look around us today and we see a little bit of bare ground, and we see a lot of bayberry, which is a native plant to our island plus some berries. And we see we basically cleared this corridor, if you would, down to the water so that visitors to the island walking the path can actually see the water and see down, see what it may have looked like many, many years ago. POWERS: A few of the volunteers are here for the first time, but most are old-timers like Ray, who return week after week to take care of the islands. Volunteer Bob Walsh drags away buckthorn branches. (Photo: Olivia Powers) RAY: I started about nine years ago volunteering with the National Park Service, doing habitat restoration as we’re doing today. There’s a few of us who come out here every week and we strongly believe that we are making a difference. POWERS: Nancy Faye is another regular. She says she’s lost count of how many times she’s been out on a Stewardship Saturday, but remembers what the islands looked like before volunteer restoration efforts began. FAYE: I’ve been coming out here since I was a child. It was a way to get away from your parents and just go away for the day and do some adventure, because nobody was out here. It was just raw; it was empty. You would never see another person on any of the islands. POWERS: The islands aren’t so empty now, but they still offer a refuge from Boston’s teeming streets and looming skyscrapers. And Nancy explains that introducing the city’s youngsters to this world on the harbor’s horizon is another of the program’s goals. FAYE: I love the educational programs that they do for the kids to expose them to something new. It’s just, it’s so close to Boston and these kids never have an experience to do that. POWERS: Today, some students from the New England Aquarium’s Live Blue Ambassador program join Nancy and the other volunteers. Here’s Hereesa, one of the high schoolers. HEREESA: What we do is we focus on habitat restoration and also invasive monitoring. We distinguish, like, an invasive plant, we monitor where they’re growing, what sites they do, and kind of promote the native species to grow and flourish. POWERS: After lunch, Hereesa and her fellow ambassadors head down to the shore to collect data on the marine life that lives on the ropes that hang off the docks. They’re led by Edgar, one of the park’s staff. [SOUND OF WAVES] Volunteers on Grape Island (Photo: Olivia Powers) EDGAR: We have some ropes here, we’re gonna pull 'em up. These invasive species that we’re looking at are sessile invertebrates, so once they land after their larval form they stay where they are for life so we’ll be able to see if they’re present or not. [STUDENTS TALKING ABOUT THEIR DISCOVERIES] POWERS: The rope is covered in slimy sea creatures. The kids pluck them off and drop them in a small bucket. They pull out laminated charts and get to work identifying the different species. The information they gather is passed on to the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management, and will be used to help protect the harbor’s marine resources. Soon, the boat back to Boston pulls up to the dock. The students scramble to grab hold of the railing as the waves hit the dock. After a long day they are exhausted, but giddy, talking about next Saturday when they head to neighboring Bumpkin Island – and what it means to be part of a program working to protect their home. Here’s Hereesa again. HEREESA: When I grow up I want to you know set an example, and also get out there. I don’t want to be just another person that’s walking on the Earth. I want to make a difference; I want to leave a mark. POWERS: At least for now, Hereesa will leave her mark, if only on the Boston Harbor Islands, as the work of the Saturday Stewards becomes a new piece of the history that the landscape tells. For Living on Earth, I’m Olivia Powers in the Boston Harbor. Related link: [MUSIC: Pamelia Kurstin, “Lush Life,” comp. Billy Strayhorn, performed during TED Talk: The Untouchable Music of the Theremin, 2002] CURWOOD: Coming up, with Pope Francis due to visit the US later this month, we meet a Jesuit priest who helped inspire the Pope’s environmental encyclical. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned. ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provides building technologies and supplies, container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International. [CUTAWAY MUSIC: Pamelia Kurstin, “Lush Life,” comp. Billy Strayhorn, performed during TED Talk: The Untouchable Music of the Theremin, 2002] Father Al Fritsch, S.J. is the Director of Earth Healing, a website dedicated to providing daily reflections on simple living and matters of faith. (Photo: Steve Curwood) CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Pope Francis, the charismatic leader of the Roman Catholic Church, is coming to the US later this month for an eagerly awaited visit. The Pope’s recent encyclical Laudato Si frames climate change as an urgent and moral issue and is driving conversations in and out of the church. The Pope’s environmental concerns go back a long way, according to the web manager for EarthHealing.info. Earth Healing focuses on Catholic care for creation, and the manager says the pontiff visited the website before his election as Pope. And the website’s creator, Father Albert Fritsch like the Pope, is a Jesuit priest with training in chemistry. I spoke with Father Albert at the rectory of the Parish of Saint Elizabeth’s in Ravenna Kentucky, which is in one of the poorest counties in the US, not far from where he grew up on a farm. FRITSCH: Well, my father was an extremely good farmer, and we took these very poor farms and turned them into very productive landscape, even crushing our limestone rock which was there and spreading it out, and of course we had rotation of crops, tobacco which was the normal crop along with mixed corn, hay and wheat. And that's what we grew on our farm along with vegetables and fruits and therefore we were mostly self-sufficient, and we never sent anything outside the farm as waste. We fed foodstuffs that were left over to the hogs and the chickens, everything was used up in our own area, what we had. CURWOOD: So you decided to leave the farm. Where did you go? FRITSCH: I went to college, went to Xavier in Cincinnati. It was a very good school. I got a undergrad and masters degree there in chemistry. Father Fritsch grew up on a farm in rural Kentucky where his family grew tobacco, corn, hay, and wheat, along with vegetables and fruits. (Photo: Todd Shoemake, Flickr CC BY 2.0) CURWOOD: And you got a doctorate as well in Chemistry. FRITSCH: Yes, I did, at Fordham, and went on to do a post-doctorate at the University of Texas. CURWOOD: So what got you interested in the priesthood? FRITSCH: Well, I saw people I really liked very much who were Jesuits. I also had a great problem with what chemistry usually involves and that is to go to a commercial institution, work for a company. I didn't like the idea of that. Academics - well that was good but I was hoping to do something that would apply the great gifts that we have with chemistry for the betterment of society especially for the poor. CURWOOD: So what was the draw of the priesthood? Now you have a doctorate in chemistry, you're concerned about how people use chemistry, and you feel yourself being drawn to the priesthood and the Jesuit priesthood at that. A coal train rolls by a few blocks from Father Fritsch’s parish in Ravenna, KY. Father Fritsch’s concern for the effects of coal mining on the landscape where he was raised eventually brought him back to rural Kentucky. (Photo: Steve Curwood) FRITSCH: Well, it was to save our own souls, of course, is the first thing that we do it for, but also immediately it is to help all other people in some way, and I didn't see that a lot of the people who were connected to career jobs and trying to make a lot of profit in the work which they did, I didn't see that that was really the calling for what I was doing myself or for the field itself. I felt that science, if you look back upon it, a lot of people over a long period of history had contributed a lot to making chemistry what it was, and in seeing this it struck me that here is a Commons that we all have, but suddenly it's been picked up by some and used and made a fortune out. And why should it, because was part of a Commons that we all had. CURWOOD: Now, you finish up your doctorate and you decide that you're going to, well, help people, and you start to do some rather practical environmental things. What kinds of things did you do? FRITSCH: Well, I began the work after my studies and I was still at University of Texas, met a young fellow in a march that we were on, and he was going to work with Ralph Nader as one of his hot shots for the summer, and I asked him, "Well,” I said “I've been looking for something that would be more of a public interest field. Would you ask Ralph if he needed somebody like that." So he did, came back the next week and said, "Yes, go and have a connection with him and see if you can work out something." We started there at the Center for the Study of Responsive Law in 1970 and the next year we set up the Center for Science of Public Interest, with two other scientists who were working with Nader, and that field I stayed with in Washington for seven years and then decided that we really needed a branch that came closer to the poor of the country and so I had a Appalachia Science of the Public Interest which exists to this day, and so Ralph Nader has been very helpful to us in helping us get donations and things even to this day and so we've been friends ever since. A strong supporter of Pope Francis’s encyclical on the environment, Father Fritsch hosts a series of discussions with his parishioners on its teachings. (Photo: Catholic Church England and Wales, Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) CURWOOD: So you decided when you were in Washington that you would come back to Appalachia where you were born and raised, to have a ministry here. Why? FRITSCH: Why did I come back? Well, one of the first grants that we had received was from Jay Rockefeller who then the treasurer over at West Virginia and he asked us to work on some surface mine issues for the state of Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Kentucky, the different regulations related to them. And so from the beginning I began to see that strip mining was really affecting parts of Kentucky where I was from and we did that type of work in Washington for a period of time, but we moved back because Washington DC is surrounded by seven of the wealthier counties of the country and yet if were going to make a simple lifestyle that people have to go to and live, we better go back to where the poor people are and see if the challenge can’t be done there first. That's why I came back. CURWOOD: So what was it like to come back here? FRITSCH: Well people were interested in the fact that we were trying to do a simple place and therefore we set up an appropriate technology center in south central Kentucky. There we had compost toilets and we started growing intensive gardens, organic ones, quite concerned about the forest itself making sure it was being taken care of well, and I got into some coal issues at the beginning but moved on into solar. We had the first complete solar house in America. We were saying that it isn't that we were just attacking what was being done wrong, but we have to look forward to a new economy that would be a renewable energy one, and so for 25 years I ran that center and I thought that was enough time, so I've come to doing more pastoral work in two of the small parishes. CURWOOD: Why do you consider caring for the Earth to be a moral and religious issue? Father Fritsch and Pope Francis are both members of the Society of Jesus; Pope Francis is the first Jesuit Pope. St. Ignatius of Loyola, depicted here in a painting by Peter Paul Rubens, founded the Society in 1534. (Photo: mark6mauno, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0) FRITSCH: Because if we don't care for it, the vitality of the earth will be destroyed. This is the deepest of the pro-life issues, for if we don't have a living Earth, we cannot live on it ourselves, and so it's also got tremendous theological implications because we believe that Christ came to save the world, and what we have never considered is that we as part of his body are now asked to save the Earth. He is our redeemer. We enter into the very act of redemption. CURWOOD: Why should Catholics in particular care about environmental stewardship? FRITSCH: Well, not just Catholic but Christian people in general have been baptized in the Lord and that means that just as Christ loved the whole of creation, we are people who are like him in every way and therefore we imitate the Lord and our love for nature and for God's creation comes from the very part of our following that we commit ourselves to. CURWOOD: Talk to me a bit about why this perspective of the Earth is important? FRITSCH: It's very important because even though in the Acts of the Apostles, some of the very first communities brought together people who shared everything in need, the big trouble was in the last few centuries we have had Marxism, which took some of the same ideas really and imposed it with an atheist background to it, but in all actuality the world is a Commons. God created it for all of us. We have found in the course of history that more of us working together can take care of it better than individuals can, and so now when we move to a society in which an immense amount of wealth can come to a few in a very short period of time, it becomes imperative for us to bring again the idea that this is a Commons and we cannot have billionaires and destitute people at the same time. It's a poorer community because Commons means that we share together and if people can't share but instead they sequester, they take everything to themselves and hold onto it, while others don't have enough, this destroys our society. CURWOOD: How did you feel when you heard about the Pope's encylical on the environment? On September 24th, 2015, Pope Francis will become the first Pope to address a joint session of the U.S. Congress. (Photo: NASA HQ PHOTO, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) FRITSCH: At first, to be honest with you, I was nervous thinking that, well, he might not say enough. You know the Pope is a very busy man. How could you write a 100 page, 40,000 word document when you're doing everything that he's doing, but really when I look at his philosophy it's exactly the same as mine. I read that encyclical and I would not disagree with a single point on it. I may have arranged it a little differently because it's a very long document, longest encyclical ever written, but at the same time I think that everything that it says is good. But it also adds a burden. We've now got a duty to spread the word as much as we can. This is talking about the needs that we have on Earth and that we have a good tradition in his second chapter from our biblical tradition that we should do something about it and it's been misinterpreted, especially by those who want to make a little fortune in thinking that we could subjugate other people, you know. But the fact is that the time has come for us to share as a people in the world, not to look at ourselves as elite or different from others but that we are together with others. CURWOOD: Tell me about your own parish's response to the Pope's encyclical. FRITSCH: Well, they all liked the idea. In fact the person that called me a Communist and walked out one time and not only do he come back but he was one that asked that we do something about this, and my feeling is that a lot of people who are climate change deniers are really honest and good people. They don't realize what is happening, and therefore I feel like a special attention must be given with a certain amount of mercy we might say and care for those who have a difficult feeling that we have to change the status quo which they've gotten some good out of the past. If we combine a sense of mercy and pastoral care with a sense that we got to change together, I think we could do more and I think this applies not only here but I really think most of my writing is directed because, see, I'm a social conservative and I am a fiscal conservative, but on political matters I guess but I believe I call myself a true conservative because I believe it goes back beyond the capitalistic system and it has to include things which are far more sharing in our past than what we have today, and therefore if I can bring that point out to people, that they can break from their politicization, you might say the partisanization of these issues, which, when I started to work, the Republicans and Democrats were all together in 1970 to 1980, I'd like to get back to that and get away from the idea that this is a political issue. This is something far deeper than that. It is a moral issue of which we all share. Father Fritsch earned a Ph.D. in Chemistry before embarking on the path to priesthood. (Photo: Ed Uthman, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0) CURWOOD: Let's see here. You give me a bit of a handout describing each of the chapters of the Pope's encyclical. I gather you're sharing this with your congregation. FRITSCH: Yes. CURWOOD: This is quite detailed and you have at one point, 10 American applications of the encyclical. So let's just briefly describe them. The first one is to read the encyclical... FRITSCH: ...second the need for personal and domestic conversion. And conversion is a second big point. We have to convert ourselves from what we've been thinking in order to save our Earth. We just cannot save it by some of the ways that we've had in the past. The third is to organize and attend meetings and church gatherings and, of course, that's why we're setting up one, and this is a doctrine that I'm sending out on our website. Climate change deniers hold that well, it's still a battle going on, there's still people that deny it. Well, our answer is that that is a situation they are trying to set up in order to prolong the profit motivation that is accomplishing for the big energies that is the fossil fuel ones, profits that will last just like they did in the past on the tobacco issue. Tobacco areas were really scientifically concluded back in the 60s that there was something really wrong with smoking tobacco and what happened in between almost 40 years it was always saying that there was some denial occurring. The merchants were denying it and therefore they were holding back from having regulations. We are having the same thing happening with fossil fuel. The differences is there it shortened the lives of about three million people. But here we're talking about the vitality of the Earth itself. Father Fritsch’s work with the Center for Science in the Public Interest and Appalachia—Science in the Public Interest spanned more than thirty years. (Photo: courtesy of Father Al Fritsch) CURWOOD: So this is the fourth point, to talk to people, those who regard themselves as climate change deniers. Now, what about your last call here? FRITSCH: The last call is the fact that not every Catholic likes what the Pope wrote and we don't know how many there are out there, but the possibility is half of them in this country. We have far more deniers, climate change deniers in this country than they have in another parts of the world. The great possibility is many of them will do what some of our presidential candidates who are Catholic say and that is that this is beyond the Pope's expertise, but the answer is, “oh, no, this is a moral issue and that's exactly where he needs to be and must stand there”. And we have to face the fact that we have to convert and have to proselytize you might say our own people to listen to what the Pope has to say, and not just dismiss it, because it's extremely important and they've got to talk about it within their family, within their church communities and we are hoping that other parishes begin to talk among themselves in an honest way about how we all have got to change our lives in order to save our Earth. CURWOOD: Father Albert Fritsch is the Rector of St. Elizabeth's here in Ravenna, Kentucky. Thanks so much for taking the time. FRITSCH: Thank you. Related links: [MUSIC: John Lennon, et al, “Imagine”, unreleased recording owned by EMI Records Ltd./Apple, 1971]

- Barrett’s “Ohio Coal Plants Want Regulators to Keep Them Alive”

- More about the problems surrounding FirstEnergy’s proposal

- FirstEnergy’s 15-year power purchase agreement via The Public Utilities Commission of Ohio

- FirstEnergy was involved with freezing some of Ohio’s renewable energy policies that saved millions of dollars

- Ohio’s renewable energy portfolio standards

- About FirstEnergy

- Bloomberg Businessweek senior writer Paul Barrett and his workBeyond the Headlines

- Food Industry Enlisted Academics in G.M.O. Lobbying War, Emails Show

- Dr. Kevin Folta’s blog response to the New York Times’ criticism

- Fukushima: Japan allows residents of Naraha to return four years after disaster

- Nuclear “Too Cheap to Meter”?Global Warming Linked to Syrian Refugee Crisis

- Syria’s climate-fueled conflict explained in a comic strip

- Marc Levy is deputy director of Center for International Earth Science Information Network at Columbia UniversityFighting Today's Invaders In Boston Harbor

Boston Harbor IslandsA Prayer to Share Earth as a Commons

- Father Albert Fritsch’s website, Earth Healing

- The Catholic Climate Covenant

- U.S. Catholic Bishops’ letter to Congress on the encyclical

- Center for Science in the Public Interest

- Appalachia -- Science in the Public Interest

- Pope Francis’ Encyclical

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation and brought to you from the campus of the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, and Jennifer Marquis. Jake Rego engineered our show, with help from Noel Flatt and John Jessoe. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more; www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth