November 6, 2015

Air Date: November 6, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

More Nuclear Power Plants Shutting Down

View the page for this story

The Entergy Corporation recently announced it would soon close two aging nuclear power plants in the US Northeast. Yet the Nuclear Regulatory Commission also granted the company a new license to operate a Tennessee reactor. Nuclear energy expert Arjun Makhijani discusses with host Steve Curwood the paradox and the viability of nuclear power in the current energy landscape. (13:50)

Shut-Down Nukes Still Worry Neighbors

View the page for this story

Massachusetts residents who live near Entergy Corporation’s Pilgrim Generating Station worry about threats from spent radioactive fuel that remain once the power plant closes. Host Steve Curwood reports. (03:15)

Sudden Deaths For Endangered Antelopes

View the page for this story

The saiga, tawny, bulbous-nosed antelopes, have roamed the Central Asian steppe since the days of the woolly mammoth, but they’re dying by the hundreds of thousands. Dr. Richard Kock of the Royal Veterinary College of London tells host Steve Curwood that bacteria reacting to the effects of climate change may be to blame for this catastrophic event. (13:50)

Man-Made Barriers to Pronghorn Migration

/ Clay ScottView the page for this story

For centuries, herds of pronghorn have traveled hundreds of miles across the west in the second longest land migration in North America. But now pronghorn often encounter barbed wire fences on private and public land that delay or halt their journey. Now, scientists and wildlife managers are developing fencing systems that allow the pronghorn to cross safely. Clay Scott reports from Montana. (06:55)

The Place Where You Live: Wyoming's Red Desert

/ Ann Stebner-SteeleView the page for this story

Ann Stebner Steele grew up in Wyoming, riding horses and hunting pronghorn. As part of our ongoing series in collaboration with Orion Magazine, she brings us this audio essay about food, family, and the Red Desert that she loves. (04:50)

BirdNote®: Whooping Cranes

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Whooping Cranes are the largest and most endangered of US wading birds. In the fall, small planes track their migration as they stop off at the Platte River in Nebraska, as Michael Stein reports for BirdNote. (02:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Arjun Makhijani, Mary Lampert, Meg Sheehan, Richard Kock, Ann Stebner Steele,

REPORTERS: Clay Scott, Michael Stein

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The mystery on the central Asian steppe. Something is killing off the critically endangered antelope called the saiga.

KOCK: It started with just a few, then gradually gained pace and over two or three days. I mean, the best description was, they were dying like flies. Eventually the landscape was completely littered with these mammals.

CURWOOD: The connection between the die-offs and microbes that climate disruption can make deadly. Also, the North American pronghorn at risk.

GILLESPIE: Well, I know when I was a kid it would be nothing to see three or four hundred antelope come down that migration trail that goes just east of my house, and we may have seen two or three herds a year. And they were everywhere, like we lived on them.

CURWOOD: But now pronghorn face new dangers in their migration. That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

More Nuclear Power Plants Shutting Down

The Three Mile Island disaster was contained because the concrete shell enclosing the reactor core was able to withstand a hydrogen explosion and fire. (Photo: Todd MacDonald, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Two of America’s aging nuclear power reactors are shutting down, thanks to safety concerns that have led to rising costs in the face of lower electric power revenues. Entergy’s Fitzpatrick nuclear power plant on Lake Ontario near Syracuse, New York, will close before the end of the decade, as will the same company’s Pilgrim Nuclear Power station near Boston, Massachusetts. In the face of growing safety problems, cheap natural gas and rising use of renewables, both plants lose money. To put the nuclear power landscape into perspective we turn to Arjun Makhijani, President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research, and former nuclear engineer.

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth, Arjun.

MAKHIJANI: Well thank you so much, Steve, for asking me back.

CURWOOD: Why is Entergy closing down these two plants within a month?

MAKHIJANI: Well these two plants have something in common. They're both single reactor sites. They're both very old which means it takes a fair amount of money to keep them going, repairing the reactors, replacing old parts, and the cost of power generally has been going down while the cost of operating these old reactors has been going up, and those lines have crossed and so these reactors are losing money and so Entergy's closing them down.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about Pilgrim here. It was considered, I understand, to be one of the three least safe nuclear power reactors in the US. Why did it become considered to be so dangerous?

MAKHIJANI: Well, first of all, the boiling water design is similar to Fukushima, and we're all aware of the vulnerabilities of that design. They don't have the kind of robust secondary containment that say Three Mile Island had, which is really what saved us from massive releases of radioactivity during that accident in 1979.

Entergy will close Pilgrim Nuclear Generating Station, on Cape Cod Bay, within four years. (Photo: Entergy Nuclear, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Wait, are you saying that if what happened at Three Mile Island happened at the Pilgrim reactor, the city of Boston would've been contaminated?

MAKHIJANI: Well, possibly, yes, because what happened at Fukushima was a hydrogen explosion that blew apart those buildings. There was also a hydrogen fire/explosion at Three Mile Island, but because it had that extremely robust thick concrete containment building, the fire was contained on the inside and the pressure increase was withstood by a containment building and there wasn't a massive release of radioactivity. The gases were released, but not the kind of release that occurred at Fukushima.

CURWOOD: Now, Entergy's also closing the Fitzpatrick nuclear power plant on Lake Ontario, it's near Syracuse. How safe is that plant?

MAKHIJANI: Well it's a similar design, and there are similar safety concerns at Fitzpatrick. Part of the problem is at these single reactor plants, the costs have been going up and the tendency to economize on maintenance is great, and so the safety margins in these reactors tend to decline and that creates problems.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, Governor Cuomo in New York says he'd rather see the Indian Point reactor near New York City closed down instead of the Fitzpatrick. What do you think of his reasoning?

The Fitzpatrick Nuclear Power Plant, which is on the shores of Lake Ontario in New York state, will close in about a year. (Photo: Entergy Nuclear, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MAKHIJANI: Well, you know Indian Point is very close to the biggest city in the United States, and so I think it's reasonable to see a faster closure to Indian Point, but I think Syracuse should not be less precious to the governor. I think the company has said it's losing money and wants to close it and I don't think the governor should be asking for the reactor to be open.

CURWOOD: Well, that plant has a lot of tax revenue. I saw a story saying it's worth north of $10, $15 million a year to the community nearby.

MAKHIJANI: Well this is the problem that is emerging, Steve, these plants do give tax revenue. They keep the schools and fire departments and police departments going, and they tend to be in rural communities and it's giving these companies leverage to basically ask for more and more subsidies. I think a two-prong remedy is necessary rather than keeping old clunky nuclear power plants going. One is we should have a community and worker protection fund, a small charge on nuclear electricity that can be used to protect workers from unemployment ,transition them into new employment. You know we give companies incentives to come, but they are to be a kind of a pension fund for communities when they die or leave. Another part of the solution of course is that this plant can and should be replaced by efficiency and renewable energy that can create a lot of tax revenues and jobs.

CURWOOD: Arjun, the Pilgrim nuclear generating station in Massachusetts provides 84 percent of the carbon free electricity in the state. Now, how significant will its closure be in terms of the state's production of low carbon electricity?

MAKHIJANI: Well you know it's true that like in Massachusetts and many areas nuclear is a significant part of the low carbon electricity, but it's also true that these plants are shutting down because they're very high cost. The highest cost nuclear plants cost more than $60 a megawatt hour to operate. Today you can buy wind power for $30 a megawatt hour and even after the tax credit expires you'll be able to buy it for $50 a megawatt hour. Why should we be spending $60 and $70 and $80 a megawatt hour for old power plants that are generating waste that we don't know what to do with instead of simply going to renewable energy? We should move more rapidly to anticipate that these old nuclear power plants are becoming costly, they've closed down and we should accelerate our renewable energy effort so we don't have these blips in carbon production when they do retire.

CURWOOD: The announcement that these two nuclear power plants will be closed, the announcement coming really in just the past month, what is that say about the viability of nuclear energy today?

Nuclear Regulatory Commission officials visit Reactor 4 at the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear complex. (Photo: TEPCO, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MAKHIJANI: A large part of the US nuclear fleet is becoming very high cost. According to the statistics of the Nuclear Energy Institute itself, the average costs of operating these reactors have increased by about 40 percent in the last eight years. That's a sign of aging and the need for some safety improvements. I think many of the reactors that are at single reactor sites or has had other features that are high-cost features are really on the way to not being competitive or already are not competitive. I don't see a very good prognosis for nuclear energy in this country.

CURWOOD: Now, just a few weeks ago the Nuclear Regulatory Commission granted a request to begin generating electricity at a nuclear reactor in Tennessee.

MAKHIJANI: Right.

CURWOOD: Now given that you told us that nuclear power really is on the way out because of competitive pressures, how is this possible?

MAKHIJANI: Well this is not a new reactor. This is a really old reactor whose construction was started more than 40 years ago in the 1970s and then its construction was abandoned more than 20 years after that in 1996, restarted in 2007 when we were promised that it would be finished for $1.5 billion if I'm recalling correctly and in four years, and it has taken eight years and $4.5 billion. This is one of the least safe pressurized water reactor designs that the NRC should never have licensed for operation in the 21st century. It has features that are different than the Three Mile Island plant we talked about which had that robust containment. This particular design, the Watts Bar 2, has been regarded as 100 times more likely to have an early containment failure compared to other pressurized water reactors like Three Mile Island. It should be a scandal that the NRC has allowed this design to be licensed at this time.

An NRC Resident Inspector observes modifications to the Watts Bar Unit 2 reactor, meant to prevent a disaster similar to what happened at Fukushima. (Photo: Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Arjun, how safe is the newest nuclear reactor technology? If somebody wanted to build one of these things with the best technology we know today, how safe would it be?

MAKHIJANI: They are much safer than the Watts Bar reactor overall. They have some vulnerabilities. The main problem with nuclear reactors is the design of the fuel that leads to meltdowns and hydrogen generation and the potential for explosions. I raised this question with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in the post-Fukushima discussions. Why have you not addressed the design of the fuel rods that creates this vulnerabilities of large amounts of hydrogen and hydrogen explosions?, and they said, “well it's a common vulnerability of all these designs and so we didn't address it”. I would've thought, if this is a common vulnerability, we should address it, and there are ways to address it, but there you are.

CURWOOD: In any event would the new style reactors be competitive in this particular energy price environment?

MAKHIJANI: They are not. We have four new reactors being built, two in South Carolina and two in Georgia. Wall Street refused to finance them. They are being built by laws that were passed by the states legislatures to require ratepayers to pay for their construction without any risk to the company. If the reactors are not finished then the ratepayers don't get their money back, and you know in the last phase of nuclear power, about 100 reactors were started or planned and not finished. If the reactors are finished even though the ratepayers finance them, they don't get to own a piece of it, and typical as the last go around, the costs have gone up and there have been significant delays.

CURWOOD: Someone listening to us will say, “what about the question of nuclear waste, Mr. Makhijani? New reactor, old reactor, they still generate this stuff, and we don't seem to have a solution for that. Why should we even be talking about nuclear power if we can't solve the waste problem?”

Nuclear waste being transported to a deep geologic repository near Carlsbad, NM. (Photo: Department of Energy, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MAKHIJANI: This is a very good question and the answer is that we shouldn't be talking about it. We should think of phasing them out and limiting the amount of nuclear waste and getting on with a nuclear repository program that makes sense. Now, it's not a good solution but it's the least bad solution. We cannot leave this nuclear waste lying around at more than 60 sites forever. Currently, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s position, however, bizarre it might sound is that we can leave these wastes at power plant sites forever, that it will be safe despite the fact that it has plutonium in it that lasts for tens of thousands of years. We're farther away from a sensible repository program than we were in 1982 when the Nuclear Waste Policy Act was passed.

CURWOOD: So Entergy says it's going to shut down the Pilgrim plant in Massachusetts, the Fitzpatrick plant in New York State. What exactly does “shutting down” that is “decommissioning” a nuclear power plant entail?

MAKHIJANI: Well this is a long tale. So, the spent fuel, the used nuclear fuel, which is highly radioactive, will remain in the pools. It may be moved to dry storage. Dry storage in some ways is safer but creates its own issues. There's nowhere to put it, of course, so the site cannot be decommissioned completely. Decommissioning is expensive because the reactors are highly radioactive, or parts of the reactors are very, very radioactive, so it takes a lot of time, effort and care to dismantle these machines. There are wastes generated from that, and so they'll have to work out a decommissioning plan. Some of these plants are just sitting around to be decommissioned later. I do think it is better to move on with decommissioning. You keep workers employed and there's some taxes that arise out of that.

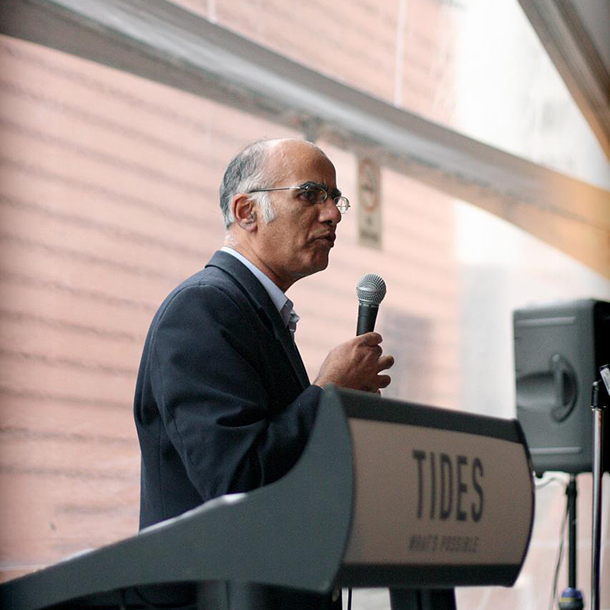

Arjun Makhijani is the President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research. (Photo: Francisco Martinez/Tides Momentum, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now my perception would be that even though decommissioning takes a long time, and there's a lot a radioactive material that stays on site, that nonetheless it lowers the risk for the surrounding public in comparison to an operating aging nuclear plant. How correct is my perception?

MAKHIJANI: You're absolutely right. There are mainly two different kinds of big risks associated with nuclear power. One of them, of course, we have seen dramatically in Fukushima is that operating nuclear reactor fails, has a meltdown and massive release of radioactivity. That is the risk that goes away when you shut down the nuclear reactor and remove the fuel. When you remove the fuel to the spent fuel pool where it is stored, you still have some risks because some of this fuel is still pretty hot and it needs to be cooled, so you can have a loss of coolant, and there are some risks of fires if you have a complete loss of coolant, but as the fuel gets older it cools down significantly and these risks do decline, and if you thin out these pools and have dry storage, the risks to the surrounding population become quite low.

CURWOOD: Arjun Makhijani is the President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research in Tacoma Park, Maryland. Arjun, thanks for taking the time with us today.

MAKHIJANI: Thank you so much, Steve, for asking me back.

Related links:

- The only nuclear plant in Massachusetts to close

- Entergy to Close Fitzpatrick Nuclear Power Plant in New York

- Say Hello to the First New U.S. Nuclear Plant in Almost 20 Years

- Half-death: Nuclear power emits no greenhouse gases, yet it is struggling in the rich world

- Nuclear power plants warn of closure crisis

- About Arjun Makhijani

- Carbon-Free and Nuclear-Free: A Roadmap for U.S. Energy Policy by Arjun Makhijani

[MUSIC: Norah Jones, Shoot the Moon, Come Away With Me, Blue Note]

CURWOOD: Just ahead...the views of the people who have lived in the shadow of the Pilgrim Plant for over 40 years. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Samite Mulondo, Nalubale, Emalasasa on Triloka, Artemis Records]

Shut-Down Nukes Still Worry Neighbors

Pilgrim Nuclear Generating Station will be shut down by 2019, but activists remain concerned about the plant’s spent fuel. (Photo: courtesy of Meg Sheehan)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. When the Nuclear Regulatory Commission found Pilgrim to be one of the three most dangerous nuclear power plants in the US, it was no surprise to some local residents as it has been the focus of protests for much of its 43-year history. Mary Lampert is the director of the citizen group Pilgrim Watch.

LAMPERT: My house is six miles across open water from the reactor. I can see it from my house, which is real motivation to get to work on the very serious issues that threaten our communities.

CURWOOD: Mary says that she and her fellow activists celebrated when they heard that Entergy had decided to close the plant, but their joy was short lived when they thought about the radioactive waste.

LAMPERT: The problem doesn’t go away. There’s no place to put that spent fuel.

Mary Lampert, director of Pilgrim Watch, testifies before the Joint Committee on Public Health at the State House on July 28th.

CURWOOD: Mary and her fellow activists are asking that the spent fuel at the least be removed from the storage pool and placed into dry casks on site. She says it’s the best they can hope for.

LAMPERT: My granddaughter will be my age and it will still be sitting on the shores of Cape Cod Bay because no state wants to be a permanent repository.

CURWOOD: Meg Sheehan is a local lawyer. Her family has lived in Plymouth for generations; she has taken the plant to court over the impact that she argues the nuclear facility has had on the local environment.

SHEEHAN: The site where Pilgrim is located was a beautiful sandy beach with a seasonal beach cottage community. Many generations of families spent summers there and we locals loved swimming and fishing and boating there. There was a vibrant fishery, a seaweed industry that provided livelihood for many families. The shellfish and marine life has been destroyed by Pilgrim’s discharge of pollutants and cooling water into the bay.

CURWOOD: Attorney Sheehan says public health has also been affected.

Meg Sheehan speaks to the Town Board of Selectmen. (Photo: courtesy of Meg Sheehan)

SHEEHAN: I have had close friends die of cancer that is linked to Pilgrim by leading epidemiologists. In fact the state’s Department of Public Health report shows a 400 percent increase in the types of cancers linked to the of manmade radiation that Pilgrim emits. And those of us who have lived there and whose families have lived there for many generations know this and we have seen our friends suffer and die of those types of cancer.

CURWOOD: And Mary Lampert says she does not want to leave supervision of the shut down and decommissioning to the federal government, which has yet to solve the waste problem. She wants the state and local governments to step in and ensure that decommissioning goes smoothly and safely.

LAMPERT: And it should be the continued responsible of Entergy to pay so that the state can ramp up and also continue its environmental monitoring to protect public health and safety. This is about public health and safety.

CURWOOD: Entergy Corporation says it has set aside nearly a billion dollars to decommission the plant and protect public health and safety.

Related links:

- Only nuclear plant in Massachusetts to close

- Pilgrim Nuclear Plant Safety Rating Downgraded

- Pilgrim Watch

- Cape Downwinders Cooperative is another group concerned about the Pilgrim plant

- About Meg Sheehan

[MUSIC: Dill Jones, In a Mist, Davenport Blues, Chiaroscuro]

Sudden Deaths For Endangered Antelopes

A mass saiga grave (Photo: Royal Veterinary College, Richard Kock)

CURWOOD: And now for a good news story at risk of going bad. With thousands of animals under threat around the world occasionally we hear of species being brought back from the brink. That includes the saiga, an antelope with a comical bulbous nose that once roamed by the millions across the vast grassland steppe from Central Europe to Mongolia. Hunters drove it to the edge of extinction before conservation efforts saved the tens of thousands left, and the population rebounded. But now the saiga are falling to a new mysterious disease that has already killed nearly 90 percent of some remaining populations. Experts recently gathered in Tashkent, Uzbekistan in an effort to solve this alarming puzzle, and Richard Kock, of the Royal Veterinary College in London was there. Dr Kock, Welcome to Living on Earth!

KOCK: It is a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: First, tell us a little bit about the Saiga. What does it look like?

KOCK: It's very unusual animal because it is a very ancient animal. It predates the mammoth. So, it's been wandering around in these large populations in the great steppe of Central Asia for tens of thousands of years and it is highly adapted to that very extreme environment where the temperatures range from minus 45 to plus 45 and it's sort of desert environment, desert steppe. So it's a tough life, and in order to survive they have to have certain adaptations. So, they're ruminants, probably one of the oldest ruminants on Earth actually, and that enables then to get the best out of the vegetation, and they have to filter the air very carefully because when it's so cold, it would freeze their lungs. So they have this extraordinary nose, a bit reminiscent of an elephant's trunk, and it sort of flaps, and it also helps with vocalization. It's a bit like the wildebeest, people will know the wildebeest sounds, it's a bit like [MIMICS SAIGA SOUND]. It's part of its way of communicating when it's migrating. They migrate over huge distances. The other characteristics, one of the fastest hoofed animals, it does up to 70 miles per hour.

Mother saiga and her calf (Photo: US Fish and Wildlife, Igor Shpilenok, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Whoa, that's a fast antelope.

KOCK: This is partly a predator avoidance. You would've had large wolf packs, not so much nowadays but in the past. I mean, they still have wolf predation, and there are a few other species they have to watch out for. So, they've adapted to that landscape, but they are definitely from pre-history and they look like it.

CURWOOD: So what was your reaction when you found out about this mass die-off of Saigas earlier this year?

KOCK: I'll give you the background. There actually was another die-off in 2010 in the Western population that's right next to Russia, and there was a second event in 2011, and I was asked to come and sort of do a retrospective assessment of what had happened, and so I went there to spend time, gathering evidence really around that die-off. Around 15,000 animals died in that event, and so that sort of started a train of events. We got to know the Kazaks a bit and we recommended that we do a monitoring program on an annual basis because these animals come together to calve; they aggregate, a bit like the wildebeest and others. They come and aggregate in quite large groups and produce their calves before they start running again on their migratory path. So, you have an opportunity every year to look at them closely, look at the mortality, and look at their reproduction and so on. So we were doing this every year since 2012, and so we were actually on site when this mortality started, and that was a unique opportunity to get good information and samples and so on for diagnostic purposes, and it was extremely shocking.

CURWOOD: What was it like to see all these animals dead on the landscape?

KOCK: Well, it was, you know, watching it from the beginning, animals start dying. So one or two is not unexpected. It started with just a few, and then gradually gathered pace and over two or three days—I mean, the best description is that they were dying like flies. Eventually the landscape was completely littered with these mammals. Very distressing, because from moving and eating normally to death was just a matter of hours. So it was hopeless. You wouldn't have had a chance of doing much to help individuals and then the calves sadly were dying after their mothers, so they...as their mothers died...these animals were very distressed. So they'd be running around bleating and not sure what to do. So, pretty distressing.

One living saiga with carcasses littering the landscape (Photo: Royal Veterinary College, Alexa Wolfs)

CURWOOD: With all of this, how many Saigas are now left?

KOCK: Well, you know we...sort of part of this ongoing activity there has been census work where they do an aerial count. That's a particular technique where you fly and then you do transects and you count and then you use a formula to estimate what the total population is. And so the population was growing nicely. From 2014 when I was there and we were so pleased to see a big population, maybe as many 300,000 animals going off into the sunset at the end of calving and it was most encouraging to see. And the count taking the death that would've taken place over winter in early May or late April was about 250,000 in that central population. There are other populations, smaller ones in the west of about 50,000, one in the south about 2,000, and one in Mongolia of about 14,000, and a small population in Russia of a few hundred. And the central population is the key population. And so we had 250,000 and then after the die-off, we monitored two sites, one of 60,000, one of 8,000 and then gradually became clear that they were about 15 die-off sites, these aggregations of animals, and the die-offs occurred at all those 15 sites, and the government agreed to do a census after this event to try and establish actually the mortality was, and using the method - there's always an error using aerial counts - so there the best survival number was 30,000 out of that 250,000. So we know roughly 220,000 the population had died, and in all those aggregations and the ones we monitored, the very surprising thing was it was 100 percent, I mean, both getting sick and dying, so that is very, very unique. I've worked in this field of infectious diseases for 35 years and I have never seen anything like that.

CURWOOD: So what are the leading notions about what happened to these animals?

KOCK: Yes, so from an epidemiological perspective, it was too quick to be an infectious disease. For transmission of an organism, like a cold virus or pathogen or something would take weeks if not months to move through a population of that size. So this whole event was more or less over in a matter of days. So we knew epidemiological this couldn't be a transmissible infection, an epidemic if you like in the conventional sense. And so we have to explore what else might be going on and we used various methods to sample and to culture and try to identify organisms that might be involved, and in all the cases we examined - we did 32 very in-depth postmortem examinations - and we were able to show this bacteria called Pasteurella multocida or a particular serotype that's associated with a disease call hemorrhagic septocemia.

Two healthy saiga sparring (Photo: US Fish and Wildlife, Richard Reading CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, wait a second. You're talking about a bacteria that generally is transmissible...

KOCK: Yeah, it can be, but in this case there wasn't time for that. So, what's characteristic about this bacteria is we call it a commensal parasite, which means that it can be latent. So in your intestine you have lots of bacteria which are your friends, basically, they help you to resist other bacteria, other pathogens, and they give balance and they help balance your immune system, and they're on your skin, too, you have many of these bacteria which are very helpful to you. Well this is not a helpful bacteria, but it can be a very neutral bacteria, so it can sit on the mucus membrane of your throat and not do anything, just live there, living off the nutrients that are available. And in that stage it's of no problem but, occasionally they can change and they have this ability to become virulent, and what I mean by that is it that they then can invade the body and cause a disease, and we've known this for many years in domestic animals and we also know of events caused by this organism in wildlife too. Even the North American bison actually, back in the '20s, they lost a lot related to this organism. So, we can confirm that that organism is involved.

CURWOOD: OK, so these microbes are there all the time. What you think set them off?

KOCK: Yeah, that's the big question. We have some evidence from these opportunist-type bacteria that they can be, for example, temperature sensitive. So if the temperature goes up in the environment where the bacteria live, then they can switch to virulence, and it sort happens through the genes actually melting, you get a sort of melting effect. If can you imagine sort of the DNA has structure, and with heat bends and changes and that enables it now to enter the cells more easily and contributes to its ability cause disease. So temperature is something that we are looking at and how that might have affected the bacteria. The other thing is stress of some kind. This disease in domestic animals has often been associated with things like transportation, if you put cattle in the truck and drive them across United States, quite often they get what is called transport fever and that was related to this Pasteurella type organism. So we know stress is involved, so the immune system is involved, and the question is what led to the immune system collapsing across a whole population. I think it's getting that idea that we talking about an area of 250,000 square kilometers. We're talking about 15 populations varying from a few thousand to 60,000 in each of those aggregations. We're talking about synchronicity in terms of the individuals as to their suddenly getting this disease. I mean it's the most extraordinary phenomenon. It's like somebody waved a wand.

Scientists standing over a saiga carcass. (Photo: Royal Veterinary College, Richard Kock)

CURWOOD: So how could say the weather and perhaps climate change have played a role here, do you think?

KOCK: Yes, so that's a good question because clearly we need to look at some overarching factors. Something in the environment that was affecting all the animals in the sense at the same time they developed this disease. So we did look for weather triggers, and just prior to the start, the temperatures had risen quite rapidly to levels of up to 37 degrees, so quite hot and then suddenly they dropped. So we had sort of a weather front come through and it caused extreme drop in temperature from around 37 down to minus 5 over about 24 hours, plus rain plus wind. You can imagine these animals which are at peak energy demand, they’ve just produced three young lambs, they are producing a lot of milk, it's a very stressful time for them, and then suddenly having lost their fur coats as well because they dropped the coat they have in winter for a summer coat, and so they have no insulation now. So they suddenly get this shock, and we know again with domestic animals it's often associated with that sort of shock, so that may affect the immune system, that may trigger the bacteria and that looks like the most likely factor.

CURWOOD: Let me just take a moment to remind some of our listeners who aren't as fluent in the metric system as most of the world is that we're talking about Fahrenheit nearly 90 degrees going down to in the 20s overnight.

KOCK: Correct. So it's very extreme and even though the animals are adapted this is a point in time when they're actually vulnerable to getting a hell of a chill. So we suspect that this is at the root of the main trigger, but there's something deeper in it because if we look now retrospectively we see that 10, 15 years ago the pattern of temperatures was in a lower range. So in these environments, the temperatures are rising. I think this is a climate change effect. With climate change we're seeing greater fluctuations and this is an example of it I think, where the temperatures are rising very high at a time of year when that would not normally happened and they are dropping very precipitously so the range of drop is much greater than would've happened maybe 200 years ago, 300 years ago. So, in a sense what we have here is a perfect storm and the thresholds for something like this to happen are reducing, and we can probably blame climate change for that.

Dr. Richard Kock is a wildlife veterinarian, researcher and conservationist. (Photo: Royal Veterinary College of London)

CURWOOD: In the meantime what are conservationists and scientists like you doing on the ground to try to save this creature?

KOCK: So we're going to continue to work closely. We have a team of international scientists from different disciplines who are going to look at a whole range of factors, and I think if we can understand this disease and the triggers and predict them, then we might be able to take measures to help them. It's not like the Serengeti where you have hundreds of different antelope and it's a very diverse system and if you lose one species I don't think most of the tourists would notice. You know, we're talking about the main mammal of this ecosystem system and everything else depends on it. So the wolves will go, a large number of species will go if this animal goes, and the steppe will become silent. That to me is why it's so important. We have to recognize this is a large area of the planet and it could go quiet and that it would be such a tragedy.

CURWOOD: Richard Kock is an expert on wildlife disease. He's at the Royal Veterinary College in London. Richard, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

KOCK: Great pleasure. Thank you.

Related links:

- Dr. Richard Kock teaches at the Royal Veterinary College of London

- More on the saiga and the investigation into their mysterious deaths

- Wildlife Disease Association

- Saiga Conservation Alliance

[MUSIC: Luminescent Ochestrii, Dreaming in Turkish, Neptune’s Daughter, NMR]

CURWOOD: Coming up...from a beast of the east to a beast of the west. They’re just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Izumi Suzuki, Home Home on the Range,]

Man-Made Barriers to Pronghorn Migration

Barbed-wire fences are obstacles for pronghorn along their migration routes south. Some pronghorn will risk injury trying to get under the wire, while others will look for a way around. (Photo: courtesy of The Nature Conservancy of Montana)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Well, the Americas have no true antelopes as classified by the zoologists, but just about everyone calls the indigenous pronghorn of North America an antelope as well. Pronghorn are graceful animals, smaller than deer, with distinctive white rumps and enormous eyes, found on sagebrush lands from northern Mexico to the southern edge of Alberta and Saskatchewan in Canada. The pronghorn are one of the fastest land animals on earth, reaching speeds close to sixty miles an hour, which helped them outrun ancient predators. But today the pronghorn has new challenges that its speed won’t help it overcome. Reporter Clay Scott has this story from the Montana-Saskatchewan border.

SCOTT: Pronghorn antelope are almost always on the move. If you watch a bunch of the stocky little gazelle-like animals long enough, you’ll see them fidget, and drift and mill about as they graze. They move longer distances as well. Some populations make annual migrations of 250 miles or more, as they trek from their fawning grounds in the north to their winter range, and back. The vast, open grasslands of the Canadian prairies mark the northernmost extent of that range. Don Gillespie is a cattle rancher in Saskatchewan, and he’s watched pronghorn his whole life.

GILLESPIE: Well I know when I was a kid it would be nothing to see three or four hundred antelope come down that migration trail that goes just east of my house, and we may have seen two or three herds a year. And they were everywhere, like we lived on ‘em, when I grew up, on antelope. That’s what we lived on.

A female pronghorn and her young look for a way under a barbed-wire fence. (Photo: courtesy of The Nature Conservancy of Montana)

SCOTT: Don says he no longer hunts pronghorn, but he still observes them closely. Every spring and fall, he says, they follow the same well-worn path through his ranch, a path they’ve probably followed for centuries. But now, several barbed wire fences cross that route. In Saskatchewan, ranchers traditionally use only two or three strands of wire, and the antelope can easily slip under the fence. But there are many more fences in Alberta, Montana and elsewhere in the animals’ range, and they’re typically built with five or even six strands of barbed wire. And that’s a problem, because for all their phenomenal speed, pronghorn do not like to jump.

JAKES: I think the idea of jumping over a fence is something that’s learned. I don’t think -- they absolutely can jump and jump high, but I think they would rather go underneath.

SCOTT: Andrew Jakes has studied pronghorn antelope and their migrations for years. He’s a postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Montana.

JAKES: It’s just they’ve adapted to the tallest things in their landscape being a sagebrush. You know, so they, you know, it’s not in their genes, if you will, to jump.

Mule deer can easily jump over fences, but this buck is curious about the fence modifications. (Photo: courtesy of The Nature Conservancy of Montana)

SCOTT: In the antelope populations Jakes has studied, – in Alberta, Montana and Saskatchewan – some individuals migrate and some stay put. He says that two-pronged strategy has helped the species survive. In their northern range, where the summers are fleeting and the winters harsh, the pronghorn need every advantage they can get. And that’s why the type of fencing the animals encounter on their migration is so critical. When a herd comes to a barbed wire fence with the lowest wire set too close to the ground, they’re forced to go along the fence – often for a mile or more – till they find a place where they can squeeze under it. The barbed wire tears their hair, exposing them to the cold. And those extra miles spent searching for a crossing add up over the course of a long migration. More miles equals more energy expended, and less time for eating. And on the northern prairies, that loss of valuable calories can be the difference between survival and starvation. Andrew Jakes has been looking for creative solutions to the fencing dilemma.

JAKES: There are thousands and thousands…hundreds of thousands of tons of fencing out on the landscape, so it’s really useful to try and identify priority areas to start doing conservation work, so we wanted to do something that was cost effective, that had buy-in from the landowners, and that would do the best by pronghorn.

Some pronghorn will walk for a mile or more, looking for a place to cross a barbed-wire fence. (Photo: courtesy of The Nature Conservancy of Montana)

SCOTT: On the Matador Ranch in north-central Montana, Andrew Jakes has an experiment already underway.

[DRIVING IN TRUCK]

SCOTT: On a windy afternoon on the Matador, biologist Brandon Nickerson drives me along a rutted dirt track through grasslands that extend for miles. He stops at a barbed wire fence. At first, it looks like any of the hundreds of similar fences in this country.

NICKERSON: For this modification it was randomly assigned a smooth wire. So basically all we’ve done is get this second-to-the-lowest wire moved up a bit to create space, and then put in this smooth wire here.

SCOTT: This innovative fence modification project was designed in part by Andrew Jakes, and carried out with the Alberta Conservation Association and the Nature Conservancy of Montana. The first step was to identify locations where pronghorn have historically crossed fences. Then researchers altered a 20 foot panel of fence adjacent to the crossing, in one of three ways: by replacing the bottom strand with smooth wire, by fixing the bottom two strands together with plastic piping, or simply by clipping the bottom strands together. The idea is to see if the pronghorn could be taught to use the modified crossings. At the Matador Ranch, Jakes and Nickerson have set up 16 such observation sites, monitored by cameras attached to fence posts.

NICKERSON: This up here is the illuminator, the infrared illuminator for at night. Then down here we have the motion sensor, and the camera lens is actually right here.

Some pronghorn face exhaustion and starvation while trying to find a way under or around a fence. (Photo: courtesy of The Nature Conservancy of Montana)

SCOTT: In the first few months of the Matador Ranch project, the cameras have produced thousands of shots: of owls perched on the fence posts, of mule deer jumping gracefully over the wires, of badgers and coyotes sliding under. Often the sensors have been triggered by nothing more than grass blowing in the nearly constant prairie wind. But the cameras have also captured many images of pronghorn antelope. Some of the animals seem to stare at the modified fence, unsure what to do. But others move easily under. The project is still in the data collection phase, and it’s far too early to draw any conclusions. Migration in pronghorn antelope, says Andrew Jakes, is a complex strategy. But knowledge of the migration routes, he says, is something that is learned and passed on from generation to generation. And he’s confident that the fence modification project can help this ancient and hardy North American animal learn new ways to negotiate the obstacles in its path, as it makes the annual trek through the prairies it’s inhabited for thousands of years.

For Living on Earth, I’m Clay Scott in northern Montana.

Related links:

- More about the pronghorn migration and wildlife friendly fences

- A study of Jakes’ on how fence location and density affect wildlife

- Jakes works with wildlife management to monitor pronghorn

- FWP removes fencing that blocked pronghorn migration near Nashua

[MUSIC: The Milk Carton Kids, Poison Tree, Monterey, Anti]

The Place Where You Live: Wyoming's Red Desert

Wyoming’s Red Desert (Photo: Ann Stebner Steele)

CURWOOD: We stay out on the vast western range now for another installment in the occasional Living on Earth/Orion Magazine series “The Place Where You Live.” Orion invites readers to submit essays to the magazine’s website and put their homes on a map, and we give some of them a voice.

[MUSIC: Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes “Home” from Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes (Rough Trade Records 2009)]

CURWOOD: Today’s essay evokes a time-honored ritual in a Wyoming landscape that Ann Stebner Steele and her family have ridden over and loved for decades.

(https://orionmagazine.org/place/wyomings-red-desert/)

STEELE: I am Wyoming born and raised, I’m the 4th generation of my family to grow up in Wyoming. Laramie, where I live is mostly basin and range kind of country, so we have the Snowy Range Mountains, and then really wide open plains with a lot of prairie type grass, and then the Red Desert which I write about in my essay is true high desert so it’s more sagebrush, a little bit hillier, and it breaks away into the Wind River Mountains. I am Ann Stebner Steele, and this is my essay about Wyoming’s Red Desert.

Sunset in Wyoming (Photo: Ann Stebner Steele)

[SOUNDS OF WIND, HORSES AND RUNNING WATER]

STEELE: First, the square that is Wyoming, the arbitrary lines that bisect geography. Then, just off center in the southern third of the state, the Red Desert, larger than the country of Wales, and within this high desert covered with sagebrush and grease-wood and scoured by wind and snow and sun, the Great Divide Basin opens. Note the Sweetwater River, a deep and surprising crack in a landscape of little water, too much wind, and dirt two-track roads that finger the ground like hairline fractures.

Ann and her husband (Photo: Ann Stebner Steele)

On the north side of the river, on a cooling fall evening, I kneel next to my brother, helping him field dress an antelope, the wind cutting sharp through the layers I wear, dark coming on fast as the sun sinks coral against the rough-edges of the sandstone and sage stretching away from us. We hurry to beat night and get back to camp and the fire’s orange heat, and I am wrist deep in the buck’s warm chest cavity before I realize that I have forgotten to put on gloves.

My brother and I were born in Rawlins, Wyoming, but we were raised in the Red Desert. These wide horizons, the sweep of sky against earth, are our home. My family has hunted antelope in this country for four generations, and the meat that we take ties us to the place as surely as the hours spent driving, walking, and studying its draws and valleys. In marrying me, my fiancé will also marry the desert, and in the years to come, he will join me in hunting, in dressing game in order to dress our table.

When he drives into camp tonight from his job in town, he will join my brother and me around the fire ring my parents built thirty years ago. Now, I feel with my thumb for my engagement ring, feel the metal encircling my finger. I hold my hand to the light. The three small diamonds and the gold band glint, muted by the richness of blood, the diamonds almost ruby in the failing light.

[MUSIC: Eddie Vedder“ Tuolumne”from Into the Wild soundtrack, (J Records, 2007)]

I grew up in a family that hunts. Both my mom’s father and my dad’s father loved hunting, it was a huge part of who they were and how they bonded with their children. And so it was through hunting and fishing as well that my grandparents first introduce my parents to the wild places. And then that kind of grew from there, and it started becoming about not just taking game, but really going into the place and forming a deep, deep connection to that place.

The view from atop Ann’s horse Tucker (Photo: Ann Stebner Steele)

Every time I’ve shot an antelope I have cried. And not in joy. Not because it was a big buck, or because of the thrill of the hunt, but because I’ve taken the life of something beautiful, and the finality of that act is unequivocal. You can’t get around it. And so for me hunting ties me more closely to that place because I am eating and animal that has lived and died at my hand in the place that I love.

Hunting is a family tradition (Photo: Ann Stebner Steele)

I think it is that kind of connection that I learned from my parents, from having a really deep map of place in Wyoming that drew my husband into our family in a really big way. He grew up as a vegetarian. When he was in high school his rebellious stage was to order a hamburger at McDonalds. So there’s this mixing of our family traditions, but they come from I think the same place, which is a reverence and respect for landscape and for the animals we share it with, and an awareness that we have to be responsible to that connection and acknowledge it, if we are going to live well on this earth.

[MUSIC: Eddie Vedder, “Tuolumne” from Into the Wild soundtrack (J Records, 2007)]

CURWOOD: That’s Ann Stebner Steele and her essay about the Red Desert in Wyoming – and you can tell us about "The Place Where You Live," if you like. There’s more about Orion Magazine and how to submit your essay at LOE dot org.

Related links:

- Read Ann’s Essay in Orion Magazine

- Orion magazine

- Ann Stebner Steele’s website

CURWOOD: You can hear our program any time on our website and get an audio download. The address is LOE.org. There you will also find pictures and more information about our stories. And we would like to hear from you. You can reach us at comments@loe.org. Our postal address is PO Box 990007 Boston, MA 02199. You can call our listener line at 800-218-9988.

BirdNote®: Whooping Cranes

Whooping Crane and Sandhills on the Platte (Photo: The Crane Trust©)

[MUX - BIRD NOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: As well as shorter days, migrating birds are a feature of this season, especially on the major routes that transit North America, like the Central Flyway from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada. Here's Michael Stein with our BirdNote®.

[WIND ON THE LAND PLUS WATER AT RIVER’S EDGE]

STEIN: We’re here this early November dawn on the Platte River in Central Nebraska. Out of the east, in the first light, flying low above the river’s braided channels comes a small aircraft.

[SOUND OF CESSNA 172 FOUR-SEATER AIRPLANE]

Whooping Cranes (© Claire Timm)

You could call it the Platte River Crane Plane. The pilot and two observers are searching for Whooping Cranes.

[BUGLING OF WHOOPING CRANES]

With a population of just 270, these birds are among the most endangered in North America. Breeding in Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada, the cranes fly south to winter along the coast of Texas. In Autumn, they pass through the Platte River Valley, typically during late October and early November.

[BUGLING OF WHOOPING CRANES]

Sandhills over the Platte (Photo: © J. Reed)

If cranes are spotted, a ground crew hurries to their location to monitor the birds’ behavior and document their choice of habitat. This careful observation is made possible by a precedent-setting court ruling giving endangered wildlife and their habitat legal standing in the use of the Platte River’s water.

Sandhill Crane (© Tom Grey)

Two planes fly every day between early October and early November. They fly at first light because the cranes, to protect themselves from predators, stand in the river’s shallow waters at night. One could do worse than to be, at dawn, an observer of cranes.

[BUGLING OF WHOOPING CRANES]

I’m Michael Stein.

http://birdnote.org/show/platte-river-crane-plane

Written by Todd Peterson

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Bugling call of Whooping Crane [WHCRguard] recorded by J. Huxmann.

Wind in reeds recorded by Gordon Hempton of QuietPlanet.com. Lapping of water recorded by C. Peterson.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2013/2015 Tune In to Nature.org November Narrator: Michael Stein

Data for Whooping Crane populations https://www.savingcranes.org/images/stories/site_images/conservation/whooping_crane/pdfs/historic_wc_numbers.pdf

CURWOOD: To see some photos of the whooping cranes, swoop on down to our website LOE.org

Related links:

- The Platte River Crane Plane

- More about Whooping Crane Migration

- The Platte River Recovery Implementation Program

- About Whooping Cranes

- Crane Trust—helping to protect cranes and their critical habitat

[MUSIC: Terje Rypdal, Byorn Kjellemyr, Audun Kleive, Ornen, ECM]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, President Obama rejects the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline as bad for America and the planet –

OBAMA: “Ultimately, if we are going prevent large parts of this Earth from becoming not only inhospitable but uninhabitable in our lifetimes, we are going to have to keep some fossil fuels in the ground rather than burn them.”

CURWOOD: What this means for US policy and the Paris climate summit, That’s next time on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation and brought to you from the campus of the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, and Jennifer Marquis. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jake Rego, Noel Flatt and John Jessoe. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Kendeda Fund and Trinity University Press, publisher of "Moral Ground: Ethical Action for a Planet in Peril". Eighty visionaries who agree with Pope Francis climate change is a moral issue for each of us. tupress.org. And Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth