December 11, 2015

Air Date: December 11, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Historic Climate Agreement Reached in Paris

View the page for this story

After working arduously for two weeks, COP21 delegates have adopted the ambitious Paris Agreement. Secretary of State John Kerry, White House Science Advisor John Holdren and Greenpeace International Executive Director Kumi Naidoo weigh in on the importance of these climate commitments and of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, rather than the earlier target of 2 degrees. Host Steve Curwood speaks with World Resources Institute Global Climate Director Jennifer Morgan about the contents of the final Paris Agreement. (12:33)

Indigenous Peoples Fight for Their Rights at COP21

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

Indigenous nations and peoples from across the globe converged on Paris for the climate negotiations to demand climate justice and inclusion in the COP21 text. Climate change disproportionately affects indigenous people, and they believe that some climate solutions undermine their livelihoods and violate their rights. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald reports on indigenous demonstrations at the COP21 in Paris. (09:02)

Financing Forests to Cut Down on Carbon

View the page for this story

The REDD program aims to restore tropical forests to offset carbon emissions and buy time for humanity to green economies. REDD has seen some limited small scale implementation, but it’s still unclear whether REDD reforms will incentivize climate innovation and achieve meaningful emissions reductions or deliver vital cashflow to small farmers and indigenous people. Host Steve Curwood reports on this lingering uncertainty. (09:20)

Canada’s Bottom-up Approach to Cutting Carbon

View the page for this story

One promising carrot-and-stick method to cutting emissions is to put a price on them with a carbon tax or cap-and-trade system. Following the recent change of government, Canada is increasingly adopting carbon pricing within and beyond its borders. Host Steve Curwood talks with Quebec Environment Minister David Huertel about the provinces’ and country’s growing carbon policies. (09:40)

Poetic Plea for the Marshall Islands

/ Kathy Jetnil-KijinerView the page for this story

The Marshall Islands are extremely vulnerable to the effects of climate change, but some still call it home. Poet Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner describes life on the island and the rising seas that threaten it, and performs her poem “Tell Them”. (06:08)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

GUESTS: Jennifer Morgan, Dan Nepstad, Abdon Nababan, David Heurtel, Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner

REPORTERS: Emmett Fitzgerald

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Negotiations on the new climate accord went down to the wire with delegates working all night sessions. But the Paris Agreement is ambitious and aims to keep global temperature rise below two degrees Celsius.

HOLDREN: The fact is that it is already a great challenge to achieve two degrees. There's been a lot of conversation at this meeting about one and a half. I would say most science and technology experts would say that one and a half is close to impossible at this point unless we can find a way to turn emissions negative.

CURWOOD: Also, indigenous peoples are uniting for climate justice and their rights as part of any deal.

FOYTLIN: The shift has been incredible and it's just going to continue. Everybody needs to jump in line and be on the right side of history because history is happening and we will win.

CURWOOD: That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In a Beautiful Place Out in the Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

[THEME]

Historic Climate Agreement Reached in Paris

Adoption of the Paris Agreement on December 12, 2015. (Photo: UNFCCC, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From the climate summit in Paris, France and PRI, this is Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: Now that delegates here have accepted the Paris Agreement it’s clear that we are in a new era for international climate diplomacy. The logjams that bedeviled international cooperation on global warming for decades have been broken. China and other major greenhouse gas emitters in the developing world will now stand alongside rich developed countries to lower emissions. And the United States is no longer opposing UN climate action. And while the pledges to cut emissions are voluntary, countries will be legally bound to verify the progress that they do make. Secretary of State John Kerry explained why this is so important for the US.

KERRY: We spent $126 billion undoing the damage from eight storms of greater intensity than we have ever seen before. That’s what we did here in the United States. I was in the Philippines and I went to the place where the typhoon came through, and it just was staggering to see the wood splintered all across the mountain, water that came up above the control tower of the airport, homes destroyed in massive numbers. And that’s the future, folks, unless we tame this monster. So this is a moment.

CURWOOD: For vulnerable countries, such extreme weather is an existential threat. That fact and many demanding voices helped delegates settle on one of the more ambitious innovations in this compact — to call for a limit in atmospheric warming to just 1.5 degrees, down from the goal of two degrees Celsius set six years ago.

[CROWD CHANTING "1.5 to stay alive, 1.5 to stay alive..."]

CURWOOD: Of course, greenhouse gases already released to the atmosphere ensure that this is an aspirational goal, rather than an achievable one. White House science advisor John Holdren.

HOLDREN: The fact is that it is already a great challenge to achieve two degrees. There’s been a lot of conversation at this meeting about one and a half. I would say most science and technology experts would say that one and a half is close to impossible at this point unless and until we can find a way to turn emissions negative. Just to get to two degrees we need to get emissions to zero in the later part of this century. And if you understand that getting to two requires zero emissions then it becomes clear that that getting to 1.5 requires negative emissions in the last part of this century. The way you get negative emissions is you have to figure out how to pull large quantities of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and sequester it in the earth. That’s very hard.

CURWOOD: Still, the science advisor thinks it’s a good thing this new figure is in the agreement.

Secretary Kerry Speaks at the UN-Sponosored "Caring for Climate" Event at COP21 in Paris. U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, joined by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, speaks at the UN-sponsored "Caring for Climate" event at the COP21 climate change summit venue at Le Bourget in Paris, France, on December 8, 2015. (Photo: State Department photo/ Public Domain)

HOLDREN: You know I think it’s valuable to talk about one and a half in part so that people understand that two is not safe. It is just the best that governments thought they could manage to achieve. We're going to see rising sea level continuing, even if we could limit to one and a half. We’re going to see more torrential down pours, more wildfires, more droughts, more of the most powerful storms. The fact is we are already seeing dangerous human interference in the climate system at .9. The goal of avoiding dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system, that’s gone. We’re already experiencing it. The question is not can we avoid dangerous. The question is, can we avoid catastrophic?

CURWOOD: Jennifer Morgan, Global Climate Director for the World Resources Institute, is a long time veteran of these talks.

MORGAN: I'm very excited about the results of the Paris Agreement. I think that countries have had a breakthrough here. The tectonic plates have shifted. This is an agreement for all countries and a common framework. It moves away from the division between developed and developing countries; still differentiates and is fair so that the countries with less capability have to do less, but everybody is on the same page, to really deal with the climate crisis.

CURWOOD: Where is science in this deal?

Francois Hollande, President of France, Laurent Fabius, President of COP21/CMP11 and UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon open the Comité de Paris meeting in the morning of 12 December. (Photo: UNFCCC, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MORGAN: Science is at the core of it, which is one of the reasons that I'm so excited. So you have not only the below 2 degrees target, that's been there a long time, but basically a decision or an understanding that that's too dangerous, based on science. And then you have a long-term goal for the agreement, which is formulated quite scientifically about a balance between human emissions and human sinks -- forests; and that those have to get down to net zero in the second half of the century.

CURWOOD: If you do the math, the commitments that the countries have put forward here would at best keep the warming from going above, say, 2.7 degrees Centigrade, and yet this agreement calls for us aiming for 1.5. How do you bridge that gap?

MORGAN: Well, I think in the real world, it means a transformation of our energy systems; it means a shift into renewables, it means more sustainable transportation systems. And the agreement itself has mechanisms in it to help drive that. The long-term goal, hopefully, will get banks to shift their funding away from high-carbon infrastructure into these clean, renewable sets of infrastructure and do much more actually than what the agreement even looks like it will do today.

CURWOOD: And what about adaptation -- that is, providing money to folks to deal with the fact that the sea levels are rising, that there are more storms, that there's more desertification -- that infrastructure will have to be changed to deal with these problems?

As the COP21 drew to a close, a demonstration near the Arc de Triomphe sought to draw attention to the red line we cannot cross if we are to maintain a “just and livable planet.” (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

MORGAN: Adaptation was a major priority for Africa and other countries here; they wanted it to have political parity with emissions reductions, because they're dealing with impacts now. The agreement has a strong adaptation component, a long-term goal to build resilience in communities and different ecosystems; it requires adaptation planning for all countries; it has a stock-take every five years to see how countries are doing on this adaptation, how much support is being provided; and also a balance on the funding will go between mitigation and adaptation. So I think it's a pretty robust adaptation approach here.

CURWOOD: So there's some new language in this I hadn't seen before. We're talking about loss and damage for the first time. What's that all about?

MORGAN: Well, there are impacts happening now around the world, and some of them are going to continue and cause damages -- irreplaceable damages, permanent damages. And the poorest countries and the most vulnerable countries wanted some assurances and mechanisms and insurance mechanisms to work with them to deal with these long-onslaught damages. And so that's a new approach -- it's an unfortunate one, because it basically means that the impacts are happening so fast that you can't adapt to everything. So you need to be thinking about these permanent damages.

CURWOOD: How do you feel about fairness, how do you feel about equity? Are the nations of the world leaving Paris feeling that there's a fair deal here?

MORGAN: In my conversations with the small islands, with the least-developed countries, my sense is that they think that it is a good step towards fairness, that the provisions here for loss and damage, for adaptation, for finance, starts to get us there. And the inclusion of the 1.5 degree temperature goal, in a way, keeps them still in existence. It's clear that there's so much more to do for them in order for this to be fair. But I think it's a good shift, it's a good start. And we just need to keep at it.

CURWOOD: How did this agreement come together? This has been very difficult to do; we saw Copenhagen go up in smoke, we saw the deal in the Hague go up in smoke; Kyoto was just sort of gaveled through with a fair amount of objection. How was this meeting of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change able to reach an agreement here in Paris that really does have everyone engaged?

MORGAN: There were so many different factors, but I think a number particularly come to mind. First was the commitment of leaders. President Obama himself spent tremendous time and energy engaging with other heads of state, working with China, working with Chancellor Merkel, Prime Minister Modi from India; that was quite different. But the other thing that just has struck me throughout this whole year is the French. The presidency of these COPs makes a big difference, and the French diplomatic approach was sophisticated, it was caring, it built trust, and at the end, I think, it has been the best-run COP I have ever been to.

CURWOOD: A number of folks from what you might call civil society aren't so pleased with this. What's your response?

MORGAN: Well, I think it's clear that this is one piece, that we are in a transformation that is going to take time; and that it means that tomorrow we have to get up and keep going. We have to keep going and shifting away from dirty fossil fuels, in building out renewable energy. But I think Paris has accelerated that pace of that shift, and I think that's a good contribution to the fight against climate change.

CURWOOD: There's no mention in this agreement about, as some would say, keeping fossil fuels in the ground. And there's some concern by folks in civil society about that. Your response?

MORGAN: If you want to get to net zero by the second half of this century, you have to leave a lot of fossil fuels in the ground.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Morgan is Global Climate Director for the World Resources Institute. Thanks so much, Jennifer!

MORGAN: Thank you.

CURWOOD: Maybe I should say congratulations.

MORGAN: Yeah, I think so! [LAUGHS]

Kumi Naidoo is Greenpeace’s International Executive Director. (Photo: UNclimatechange, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Climate justice activists took to the streets again as the Paris Agreement came together. More than ten thousand people gathered near the iconic Arc de Triomphe in downtown Paris to stretch a giant red banner symbolizing a red line that they say we cannot cross if we are to maintain a “just and livable planet.” They argue the Paris agreement does not go far enough, and the world needs to totally decarbonize its economy as quickly as possible and keep fossil fuels in the ground.

[CHANTING: Hey hey, ho ho, fossil fuels have got to go . . . hey hey, ho ho, fossil fuels have got to go . . .]

CURWOOD: Kumi Naidoo, Executive Director of Greenpeace International, says this kind of challenge is not new.

NAIDOO: If history teaches us anything, when humanity has faced a major challenge or a major injustice, those struggles only move forward when decent men and women stood up and said, “enough is enough and no more. We’re prepared to put our lives on the line, we’re prepared to go to prison if necessary.” And given that many of the most powerful leaders on our planet seem to be all having a similar health problem, which is they all sadly having a problem with hearing the appeals of their citizens, we know that civil disobedience is something that gets them to sit up and take notice.

CURWOOD: Greenpeace International Executive Director, Kumi Naidoo. And you’ll find more at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Paris climate talks: With a final deal elusive, a push for compromise

- The latest developments from COP21 as the UN climate summit enters its penultimate day

- Aggregation of News and commentary on the Paris Climate Talks from Nature

- Chasing a Climate Deal in Paris, updates from NYT

- Once Ignored, 1.5°C Climate Goal Gains Momentum

- With France still on edge, climate negotiators search for consensus

- Arc de Triomphe: the best- and worst-case outcomes for the Paris climate talks

- Moments from the COP21

- Read the draft Paris Agreement text

- Nations Approve Landmark Climate Accord in Paris

- Protesters hold 'red line' climate demo

[MUSIC: Gato Barbieri, “Last Tango In Paris: Jazz Waltz,” comp. Gato Barbieri, Last Tango In Paris: Original MGM Motion Picture Soundtrack (Rykodisc 1998)]

CURWOOD: Just ahead indigenous activists take to the water for climate justice -- stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Gato Barbieri, “Last Tango In Paris: Jazz Waltz,” comp. Gato Barbieri, Last Tango In Paris: Original MGM Motion Picture Soundtrack (Rykodisc 1998)]

Indigenous Peoples Fight for Their Rights at COP21

A flotilla of indigenous peoples demonstrate to be heard. (Photo: Joe Soloman, Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood in Paris. Indigenous peoples from around the world had a strong presence at COP21, with press conferences, panels, and protests demanding that indigenous rights be protected in any climate agreement. One unique display of indigenous unity and solidarity took place nowhere near the conference center where the talks were held. Living on Earth’s Emmett Fitzgerald has our story.

FITZGERALD: On a quiet Sunday morning in the heart of Paris, indigenous activists descended on the Bassin De La Villette, an artificial lake connected to the city’s canal system.

[CHANTING AND SOUND OF PADDLES]

FITZGERALD: About 50 people stood on a green footbridge bridge above the water, draping banners over the side that read “Indigenous Peoples Defending Mother Earth,” and “Defend the Sacred, Protect the Water.”

[SINGING AND HORN SOUNDS]

FITZGERALD: A green canoe led a flotilla of kayaks across the lake and under the bridge. Men beat drums from the bows of canoes. One blew on a horn, and the sounds floated out across the placid water.

[HORN SOUNDS]

FITZGERALD: The term ‘kayaktivist’ was coined this summer when protesters in kayaks blocked a Shell oil rig heading to the Arctic from Seattle. Some of those activists were from the Lummi nation in Washington State, and there were Lummi paddlers on the water in Paris as well.

MAN: We come from a great canoe nation. The water is our home. We came many miles to share our traditions of keeping our environment, our home, mother earth, keeping her alive and healthy. She is alive, she keeps us alive.

[CHEERS]

FITZGERALD: But it wasn’t just the Lummi who traveled great distances to be here. Indigenous activists came to Paris from New Zealand, the Amazon and the Arctic as well.

GOLDTOOTH: It’s key that we are here as indigenous peoples because we are the frontline communities. Our communities are the first ones to feel the effects of climate change.

FITZGERALD: Dallas Goldtooth is an organizer with the Indigenous Environmental Network in the United States. He says that indigenous peoples are nature’s best stewards, and they deserve an integral place in any climate deal.

GOLDTOOTH: People have come to Paris to discuss the solutions to climate change, not aware that the solutions to climate change are right here.

FITZGERALD: When the kayaks reached the shore, indigenous leaders in traditional clothes crammed into the hull of a canal barge, where they spoke about the impacts of climate change on their homes and the need for native peoples to stand together against fossil fuel extraction. The Sarayaku people have been fighting oil drilling in the rain forests of Ecuador. Sarayaku leader Felix Santi presented a proposal he called the “The Living Forest” demanding recognition of their territory as sacred land, protected from oil, mineral, and timber extraction.

Indigenous peoples fight for climate justice in solidarity. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

SANTI: [SPEAKING SPANISH]

[TRANSLATION] And this proposal respects all the living beings and helps achieve the balance of the planet and Mother Earth. Indigenous peoples live with this wisdom, live in harmony with these living beings, and we’re here to protect the lagoons and water and the trees and the mountains.

FITZGERALD: Faith Gemmill wants to protect her sacred land too. She’s a Native Alaskan organizer with REDOIL, Resisting Environmental Destruction on Indigenous Lands.

GEMMILL: We’re calling for a full phase out on fossil fuel development.

[CROWD:YES!]

GEMMILL: And a moratorium. Keep it in the ground.

[CROWD: YES!]

GEMMILL: No more new fossil fuel development.

FITZGERALD: Faith and her people celebrated a victory earlier this year when Shell abandoned its plans to drill offshore in the Arctic.

GEMMILL: But immediately following that our state and our Congressional representatives called for drilling in the last five percent of America’s only Arctic coast, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, which is sacred to my people.

FITZGERALD: Faith says that indigenous people are doubly impacted by fossil fuels. The extraction often occurs on their land, and then they experience the worst effects of climate change.

GEMMILL: Climate change impacts our traditional livelihood and our ability to access our foods. The ground we walk on is literally melting beneath us. Whole communities are at threat of being climate refugees as they are being forced to relocate.

FITZGERALD: Here in Europe, indigenous peoples of the north face similar challenges. Jannie Staffansson is Saami.

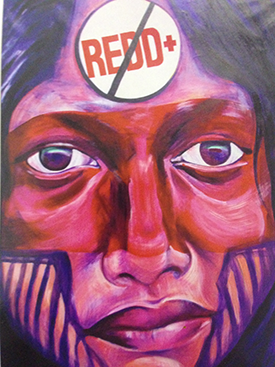

Many REDD/REDD+ climate solutions ignore the needs of indigenous peoples, their lifestyles and use of the land. (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

STAFFANSSON: The Saami are the indigenous peoples of the north, colonized by Norway, Finland, Sweden, and Russia. Our traditional livelihood is nomadic following the reindeer migration patterns.

FITZGERALD: Climate change has brought new species and strange weather to northern Europe, and it’s hindering the herders’ ability to follow the reindeer.

STAFFANSSON: My friend he couldn’t gather the herd because the lakes are not freezing and the rivers are still open. He can’t get over to the herd and the herd can’t come to him.

FITZGERALD: The Saami spend a lot of time out on the frozen lakes, and Jannie says the strange weather makes it difficult for them to predict how solid the ice will be at any given time.

STAFFANSSON: During the spring I hate when the phone rings because I’m afraid it’s bad news, somebody gone through the ice.

FITZGERALD: Jannie told her story many times here in Paris, but she says she didn’t feel like people inside the UN summit really heard her call to protect her people.

STAFFANSSON: When you’re young, you think that grownup peoples, they are the ones to protect you and they are right and they have all the answers and they will act rightly upon them, but when you notice that they do not want the best for you and they have all this information and not acting upon them, makes you very angry.

FITZGERALD: Indigenous activists in Paris want ambitious efforts to tackle global warming, but they’re concerned that some projects designed to rein in carbon pollution are being implemented without their permission, and violate their rights and undermine their livelihoods. The UN program REDD, Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation, is intended to harness the carbon-sucking power of trees in the fight against climate change. But Berenice Sanchez, a food expert from Mexico, says that too often projects ignore the important role indigenous peoples play as stewards of the forest. She’s particularly concerned that some carbon sequestration projects are making it impossible for her people to live as they have for generations.

SANCHEZ: [SPEAKING SPANISH]

[TRANSLATION:] The implementation plans aren’t respecting traditional knowledge, or the methods people have used to care for these places. In Oaxaca, for example, what traditionally has been done is people harvest firewood to use in their homes. This is an activity that you can’t do anymore. It’s not our forest anymore.

FITZGERALD: Back at the water, a sign on the bridge reads NO REDD in bright crimson paint. Casey Camp Horinec of the Ponca nation in Oklahoma says you can’t put a dollar figure on a forest.

HORINEC: We do not buy and sell the air, we do not buy and sell the water, we do not buy and sell the earth, we do not buy and sell the fire.

FITZGERALD: Indigenous activists lobbied hard in Paris for a strict requirement that countries protect the rights of indigenous people in any efforts to address climate change, but as of recording this, that language was removed from the binding text.

GOLDTOOTH: You know the nations of the world are concerned about legal liabilities, if they’re held accountable to recognize the rights of indigenous peoples, and so they would rather cut that put than put that in.

FITZGERALD: Dallas Goldtooth says they will keep pushing for climate solutions that protect indigenous ways of life.

GOLDTOOTH: We’re on the edge here. We’re on the brink of extinction. It does not matter whether you are indigenous or not indigenous, we all stand on common ground literally. We need to protect it at all costs. The only way that we can keep the temperature from rising is to keep fossil fuels in the ground.

FITZGERALD: But that wasn’t on the table in Paris. The final climate deal won’t satisfy all the activists on the water, but Cheri Foytlin, a Cherokee Dene writer from Louisiana, says her spirits are still high.

FOYTLIN: You know what the best part about this is...just seeing all these amazing people stand up and say they’re going to take back their world.

FITZGERALD: Cherri says that indigenous people from across the globe paddling together through the center of Paris sends a powerful message that the movement for climate justice is growing.

FOYTLIN: The shift has been incredible and its just going to continue. Everybody needs to jump in line and get on the right side of history because history is happening and we will win.]

[CHANTING]

FITZGERALD: For Living on Earth this is Emmett FitzGerald in Paris.

Related links:

- UN-REDD Programme

- About REDD+

- Indigenous Peoples’ Caucus Focuses on Setbacks at COP21 as Agreement Moves to Final Negotiations

- UN promoting potentially genocidal policy at World Climate Summit

- NO REDD in Africa Network

- Some REDD climate projects in the Americas

- Documents involving REDD/REDD+

Financing Forests to Cut Down on Carbon

Deforestation in the state of Acre, Brazil (Photo: Kate Evans/Center for International Forestry Research, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Whatever the indigenous communities may want for their forests, we cannot survive without the world’s trees. How to save and rebuild tropical forests prompted a lot of discussion here at COP21. The Amazon alone has enough forest carbon to equal more than a decade of present fossil fuel emissions, and Central Africa and South East Asia are nearly as carbon rich. New analysis shows that the tropics could theoretically save a whopping four to six gigatons of carbon a year if deforestation is halted and the trees are allowed to grow back, says Richard Houghton of the Woods Hole Research Center. That would be like cutting a third of the world’s annual industrial CO2 emissions..

HOUGHTON: ...which is enough to stabilize the concentration of carbon dioxide now and keep it stable as we come off of fossil fuels.

CUTWOOD: But to make such sharp carbon cuts, Houghton says, the world would need to stop cutting virgin forests, restore them, and at the same time drastically reduce the logging of plantation trees used for pulp and paper. He also says small farmers who repeatedly slash and burn small areas of forest to enhance crop production would have to rethink their methods.

The idea of saving tropical forests to buy time for humanity to convert from fossil fuels led to the concept known as REDD, reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. It’s been around for a decade and got more encouragement at COP21. But making this forest protection concept a reality has been tough, to say the least, as Mariano Cenamo of the Institute for Conservation and Sustainable Development of the Amazon noted at a COP21 side event.

CENAMO: The first main challenge is to reduce deforestation at the same time they promote social and economic development. As we know, the main driver of deforestation in most these regions come from the need for economic development, from agriculture, cattle ranching, mining and other illegal logging. And therefore to substitute these activities that generate revenue for another land use activity we need investments, this is what we need now, this is what is not in place on the needed scale so far.

CURWOOD: At COP13 in 2007 in Bali, REDD proponents won strong support for financing those needed investments out of the global carbon markets. Countries that reduced emissions by saving forests would have been paid for that performance with credits exchangeable for cash. Companies wanting to offset their carbon pollution could buy those REDD credits. But two years later, when COP15 in Copenhagen failed to reach a broad mandatory international cap and trade agreement, REDD’s future became uncertain.

NEPSTAD: Coming out that sort of disappointment in Copenhagen in 2009 that left space for sort of the voluntary markets to start to move forward. The whole generation of carbon cowboys came out, that is sort of speculators that someday carbon from forests and from reductions of deforestation would take on some value.

CURWOOD: That’s Dan Nepstad, a tropical biologist and REDD expert who heads the Earth Innovation Institute in San Francisco. Without international standards and with no clear regulations he says a good concept at times became a bad practice.

NEPSTAD: A lot of people went around signing off contracts with getting indigenous people to sign off contracts sort of giving away their forests in a way. That was a phase of REDD that continues at some level that got a lot of bad press and it should have gotten a lot of bad press. I think that is unfortunate. I think that Chiapas, for example, it’s been assumed that somehow California is putting money into a project that is taking land away from Lacondon Maya Indigenous group and is simply not true. So there was also a lot of misinformation out there.

CURWOOD: But there have been some good news stories, based on bilateral deals, even though a broad multinational system has yet to be implemented. For instance, Brazil has avoided some four billion tons of carbon emissions since REDD came along. In recognition, Norway has given Brazil more than $130 million to cover some of the costs of implementing REDD, though it’s unclear how much of that has trickled down to small farming and tribal communities.

Now, here in Paris, the notion of tradable carbon offsets for REDD performance was mostly not on the table. Brazil in particular objects to the idea that REDD credits could help dirty industries continue carbon pollution. Instead, COP21 promoted bilateral deals between nations and even provinces as new workable REDD mechanisms that mesh with the diverse INDC system of carbon reduction pledges.

About 20 percent of the world’s tropical forests are in indigenous territories, and many of these lands have changed little in hundreds if not thousands of years, even though the communities there are now developing and farming. But indigenous people seldom hold title to those lands that mainstream courts recognize, and the REDD discussion has brought about some welcome clarity. Again, Dan Nepstad.

Reforestation in Burkina Faso (Photo: Atamari, Wikimedia Commons)

NEPSTAD: It was in the context of the development REDD program in Indonesia that the constitutional court decided customary land rights, that is the rights of Dyak communities, other ethnic groups who have been there forever but never formally recognized because its government land need to be ceded back to those communities. That is a mind-boggling decision by the court. It has to be implemented and that’s a big step, but the context for that was the REDD debate. And how can we get benefits to people who don’t have clear claims to their land.

CURWOOD: Global indigenous leaders say there are other basic elements beyond land rights that their communities need to participate in REDD, and those include free, prior informed consent, and financing for land protection. They also say they need an end to the criminalization of human rights activism and recognition of the contribution of indigenous peoples in the fight against climate change. I caught up with Abdon Nababan of Indonesia, Secretary General of Indigenous Peoples' Alliance of the Archipelago for his assessment.

NABABAN: I think nothing wrong with REDD. If the implementations put indigenous peoples' rights as a precondition. We have the same goals with REDD+ to reduce deforestation and forest degradation, but if they put that in a market scenario, if they put REDD into the hands of corporations, the REDD + will colonize our territory.

CURWOOD: For a moment, let's pretend we are in the forest looking around at the various trees and other plants, what would we see?

NABABAN: Now, there is mixed situations in our forest in my homeland. You can see the very good forest with the agroforestry systems in our land, but at the same time, there is a new industrial forestry came to our land that converted this agroforestry systems for pulp and paper, so now we see the two. We see how the indigenous keep the forest but also we will see how the system will become treated by the industrial timber industry. I hope that the governments, and also the academics work to produce the knowledge systems that this monoculture systems will destroy our indigenous systems.

CURWOOD: The fires burning now in Indonesia, why are they a sign that indigenous rights are not being respected?

NABABAN: Because now most of our forests are already granted to the corporations and they want to dry the rainforest and also the peat lands to become plantations for oil palm. That's why there is opposition for indigenous peoples' rights from the extraction industry.

CURWOOD: What will it take to wake up the world to this solution to forest loss and degradation? In other words, recognition to indigenous rights?

NABABAN: I think the solution for right now is to bring all kinds of low-carbon lifestyle to be in the front lines of this fight, and indigenous peoples is one of them. Of course, not only indigenous peoples, they are also local communities that's also already developed their own system to be more organic, for example, organic farming and so on. That would be the solution for what are facing right now that we call climate change.

CURWOOD: And by the way, if you’re not familiar with Abdon Nababan’s term of agroforestry, it mixes trees and shrubs with crops and pasture to make food production more diverse, more sustainable and even more profitable — and can eliminate the need to cut down many trees.

As the delegations headed home from Paris, it’s still uncertain whether this time the money will truly flow to keep and restore this resource that can help control global warming— tropical forests, the lungs of our planet.

Related links:

- About REDD+

- The incredible plan to make money grow on trees

- Climate talks: rich countries should pay to keep tropical forests standing

- Tropical forest losses outpace UN estimates

- What’s the best way to protect forests? That’s a big question at the Paris climate talks

- “Forest Management: An Interim Strategy to Transition Away from Fossil Fuels,” by Richard Houghton

- About Dan Nepstad

[MUSIC: Francis Lai, “Un homme et une femme,” comp. Francis Lai, Un homme et une femme (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) (Les Films 13 2012)]

Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line anytime at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-99-88. Our e-mail address is comments@LOE.org. That's comments@LOE.org. And visit our webpage at LOE.org. That's LOE.org.

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Coming up...a voice from the heart of an endangered Pacific island. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provide building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Gato Barbieri, “Jeanne,” comp. Gato Barbieri, Last Tango In Paris: Original MGM Motion Picture Soundtrack (Rykodisc 1998)]

Canada’s Bottom-up Approach to Cutting Carbon

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at COP21 (Photo: Province of British Columbia, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood at the climate summit in Paris. In the crucial lead-up to these talks, countries were asked to prepare emission cutting plans or INDCS, and that focused negotiations much earlier than in previous rounds. The question now becomes, how do countries actually hit the targets they have set, which will only “ratchet up” in the coming years. One answer is a sort of bottom-up approach, with individual cities, states, and provinces making the changes necessary to help their nations meet the goals—and even reach across international borders. A good example of this is Canada.

Newly elected Prime Minister Justin Trudeau came to Paris to say that Canada is now backing federal and provincial climate protection, after a decade under conservative leader Stephen Harper who pulled out of the Kyoto Accord and championed oil sands development.

TRUDEAU: A lot of you may have noticed that over the past ten years of so Canada has been, perhaps less enthusiastic than some about addressing climate change and its impacts. But even though at the federal level we haven’t necessarily been strong and active at the subnational level our provinces have stepped up. We have four different provinces that represent about 86% of the Canadian economy that have actually moved towards putting a price on carbon.

CURWOOD: Trudeau pointed to renewable energy development and energy efficiency as engines of growth.

TRUDEAU: We are now in a race to see who can be the most efficient. Who can create the best technology for renewable energy for moving forward in a way that understands there is no longer a choice to be made between what’s good for the economy and what’s good for the environment.

CURWOOD: And a key stimulant of green energy development, Trudeau says, is putting a price on carbon, which is well underway in several Canadian provinces. Quebec has been a leading Canadian province on carbon pricing, working with other provinces and even US states. To explain how this all works we turn to David Hertel, the Minister of Sustainable Development, the environment, and the fight against climate change for the Province of Québec.

HEURTEL: So we’ve set up a carbon market, which we've successfully linked to the one set up in California, creating the largest carbon market in North America, and we've been very successful at raising revenues. First of all, the carbon market has allowed us to raise close to a billion dollars in revenues on our way to our target of $3 billion by 2020, and that money is entirely reinvested in Québec's green fund which funds different adaptation and mitigation measures, for example, public transit, electrification of transportation, investment and renewable energy, energy efficiency research also and climate change impacts in Québec, and also the development of the whole clean tech sector so it's important to know that while we're fighting climate change with the carbon market because our carbon market is directly linked with our emissions reduction targets, this current market allows us to achieve those reductions but also is a tool for economic development to transition out of a fossil fuel-based economy to a cleaner economy.

CURWOOD: Without getting into too much detail, how does this work? If I'm in Québec, how am I being charged for the price of the carbon I use?

HEURTEL: If you emit...let's say you're the CEO of a major industrial company which emits more than 25,000 tons of CO2 per year, you are automatically by law integrated into the carbon market, and so if you want to continue to operate anything over 25,000 tons you have to acquire, you have to buy, carbon credits.

CURWOOD: And how much are those?

HEURTEL: The last auction, the price was set ultimately at $17 Canadian a ton, which is about $12, $13 US, and what's very interesting is that the price has been progressing. It started in 2013 at closer to $10 Canadian so now it's actually progressing and that's the basis of a successful carbon market because it creates the incentive for the private sector to change their ways because if a company buys carbon credits, and then invests in cleaner technologies then it can sell the unused credits on the open market and actually make money, and also it doesn't have to buy as many credits as it would've normally it had continued on the old way of doing business.

CURWOOD: So how does your subnational system, that is the provincial system, mesh with the others? You have a deal with California but at the same time there's a tax in British Columbia, I believe Manitoba is getting involved in this, Ontario I believe is also getting involved in this, and I imagine that the systems and the numbers aren't all exactly the same. How do you put that together?

HEURTEL: Well, we work at it, quite honestly. With California, it took several years, but we were able to harmonize our regulations and have a completely regulated system, which works and now Ontario has indicated not only that he wants to set up its own carbon market but it wants to link up with the Québec California model, so it's going to be one whole integrated system. Same thing with Manitoba. So were talking about one block.

The key here is that we first need all to establish a price on carbon to effectively fight climate change. I mean, we're here at the COP. I think it's something that enjoys a broad consensus. We need to establish a price on carbon, and what is interesting is that now while maybe five, six, 10 years ago, nobody was talking about carbon pricing in Canada, now you have five provinces looking at carbon pricing, representing over 80 percent of its population. So we're moving in the right direction, but I think also provinces have to put in place the right system for their economies, and for their population, for their particularities. And we can work together from that basis.

CURWOOD: You've looked over the border to the U.S. and California, what about the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative in the east coast of United States?

HEURTEL: So obviously that's very interesting market as well, nine US states all in the Northeast, including all the four border states with Québec. We've had very interesting exchanges, Premier Couillard has met several times with the governor Shumlin of Vermont, we're very cited by Gov. Cuomo in New York state in the recent announcement, I think it was in October and he announces intent of broadening the scope of RGGI and maybe eventually even looking, he specifically mentioned the Québec California market and looking if there wouldn't be any possibilities of linking up or collaborating. And there have been exchanges between WCI which is the entity which governs the Québec California market and RGGI to see if there could be some preliminary ways of aligning both markets, so that's very exciting news as well. Same thing on the west coast, Washington state and Oregon have taken significant steps and are interested in looking at establishing carbon pricing and eventually maybe carbon markets that could be linked with the Québec California model. Mexico has also showed interest. There was a MOU that was signed by Premier Couillard with the Mexican president on October 12 of this year which says specifically at both Québec and California will explore with Mexico the possibility of linking Mexico's carbon market which should be online by 2017 with the Québec California model. So as you can see, there's a lot of momentum, there’s a lot of things going on in the right direction, so it's pretty exciting time right now.

CURWOOD: What advice would you give to the United States based on your experience with carbon trading? People tend to say, OK, well right now it's unlikely a Republican Congress will do this, but times do change as you found yourself in Québec, so how would you advise the United States to proceed with dealing with the price of carbon if you were asked?

HEURTEL: Well, that's a pretty tall order. I think what we need to look at and if I can speak to the Canadian experience, I think if you look at the infranational level, so that's the state and local level, that's where the main jurisdictions are, the main powers are to affect real change, and we’ve seen it in Canada. It's the provinces, it's the territories and the cities that have forced the real change and put in place the real measures that we see now are working. So you don't necessarily have to wait for your national government to move.

CURWOOD: There are some who criticize carbon pricing as leaving the door open to burning more carbon. They said we should just shut it off. What you say response of those criticism?

HEURTEL: That has not been our experience. Quite the contrary, the setting up of the cap and trade system in Québec has helped us effectively reduce remissions and has effectively also help business transition out of fossil fuel-based technologies and develop new technologies. They factored in the cost and they see that there's actually opportunities for growth. Our economy now is positioning itself to be a leader in exporting these new technologies around the world.

CURWOOD: David Heurtel is the Minister of…

HEURTEL: Minister of Sustainable Development for the environment and the fight against climate change of Québec.

CURWOOD: Thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

HEURTEL: Great to speak with you. Thank you so much.

CURWOOD: And by the way, New York governor Andrew Cuomo has said that he would like to work with the Canadian provinces and California to develop a broad North American carbon market, using cap and trade. And for New York State to go beyond exchanging credits related to RGGI, it would have to create a state or regional cap and trade system itself.

Related links:

- Canada pushes role of carbon markets in reducing emissions at climate summit

- About carbon pricing

- The carbon tax, an idea with appeal

- Cap and Trade vs. Carbon Tax

- Gov. Cuomo aims to link U.S. Northeast’s carbon market with California’s

- Justin Trudeau tells Paris climate summit Canada ready to do more

- About the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI)

[MUSIC: Louis Armstrong, “All That Meat and No Potatoes”, comp. Ed Kirkeby/Fats Waller, Satch Plays Fats (Columbia/Legacy 2000)]

Poetic Plea for the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands are threatened by rising seas. (Photo: BermudaMike, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: For observers, the flurry of high level negotiations and proposals and agreements and pledges from business and individual nations were overwhelming. But there were alternative moments of calm. Artists converged on Paris as well, to express their climate truths and try to reach the 40,000 people gathered at the conference center, and the millions of Parisians.

Among them were some writers and we caught up with one from the Marshall Islands, who performed her poem “Tell Them” and talked about her home.

JETNIL-KIJINER: My name is Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner, I’m from the Marshall Islands. The Marshall Islands is in the Northern Pacific Ocean and it's in an area called Micronesia. It's a small country, it's not very developed. You know, there's just one road, like just one main road, running through the entire island. There's no traffic lights, no malls, no Burger King, none of that happens there. It's very very flat, there's no mountains at all, it’s just ocean all around you, which I heard people say that kind of scares them.

[SOUND OF GENTLE WAVES]

It freaks them out when they're first there, like everywhere you turn you see the ocean. And there's coconut trees. Some parts are really lush and beautiful, some parts are not. Our people were known to be canoe navigators, we're also known to be fine mat weavers. And there's just kids everywhere.

[SOUNDS OF KIDS PLAYING AND WAVES]

You just see kids running around all over the place. Basically, Marshall Islands is only one meter above sea level and so we're extremely vulnerable to the rising sea level. We have these things called the sea walls, which we built to keep the ocean out of their homes, and recently we've been having multiple floodings. Just within this year alone, we've had four breaches...water being so high that it would crash into our homes, destroy, completely obliterate and destroy homes, like completely level it out.

I was out two weekends ago running errands, and I saw these women and children fundraising with a car wash and BBQ plates, and so I went to buy a BBQ plate. And I said, "What are you fundraising for?" And the women, said, “our sea walls are broken”, and I was like, "Oh, from the recent flooding?" And they said, yes, just the recent one. "It broke all of our sea walls." It was a whole community of houses whose sea walls were broken. And they sent me all of these photos of these completely messed up sea walls, parts of their houses just totally messed up. And you know, they're not rich, these people. They're having to figure out ways to fix their sea walls, raise funds. Our minimum wage is $2 an hour. And so we're already struggling as it is, as a people, as a country. But then, we have climate change on top of it and it just exacerbates the situation.

I'm a poet and performer. I'm actually here with the Global Call for Climate Action. GCCA brought me and four other poets out here for the Spoken Word for the World project to raise awareness on various issues on climate change. Our poetry is meant to bring the humanity back into the issues that we're discussing.

TELL THEM

I prepared the package

for my friends in the States

First, the dangling earrings woven

into half-moons black pearls glinting

like an eye in the storm of tight spirals

Second, the baskets

sturdy, also woven

brown cowrie shell shiny

intricate mandalas

shaped by calloused fingers

Inside the basket

I write a message:

wear these earrings

to parties

to classes and meetings

to the corner store, the grocery store

or while riding the bus

Store jewelry, incense, copper coins

and curling letters like this one

in this basket

And when others ask you

where you got this

you tell them

they're from the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands are comprised of 1,156 islands and islets. (Photo: Keith Polya, CC BY 2.0)

show them where it is on a map

tell them we are a proud people

toasted dark brown as the carved ribs

of a tree stump

tell them we are descendants

of the finest navigators in the world

tell them our islands were dropped

from a basket

carried by a giant

tell them we are the hollow hulls

of canoes as fast as the wind

slicing through the Pacific sea

we are wood shavings

and drying Pandanus leaves

and sticky bwiros at kemems

tell them we are sweet harmonies

of mothers, aunties, sisters

songs late into night

tell them we are whispered prayers

the breath of God

a crown of fuchsia flowers encircling

Auntie Mary’s white sea-foam hair

tell them we are styrofoam cups of Kool-Aid red

waiting patiently for the ilomij

we are papaya-golden sunsets bleeding

into a glittering, open sea

we are skies uncluttered

majestic and sweeping in their landscape

tell them we are dusty rubber slippers

swiped

from concrete doorsteps

we are the ripped seams

and the broken door handles of taxis

we are sweaty hands shaking another sweaty hand in heat

tell them

we are days

and nights hotter

than anything you can imagine

tell them we are little girls with braids

cartwheeling beneath the rain

tell them we are shards of broken beer bottles

burrowed beneath fine white sand

we are children flinging

like rubber bands

across a road clogged with chugging cars

tell them

we only have one road

Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner is a Marshallese poet, writer, performance artist, and journalist. (Photo: Simon Ruf/UN Social Media Team, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

and after all this

you tell them about the water

tell them how you have seen it rising

flooding across our cemeteries

gushing over our seawalls

and crashing against our homes

tell them what it's like

to see the entire ocean level with the land

tell them

we are afraid

tell them we don't know

of the politics

or the science

but we see

what's in our own backyard

tell them some of us

are old fishermen who believe that God

made us a promise

tell them some of us

are a little more skeptical

but most importantly you tell them

that we don't want to leave

that we've never wanted to leave

and that we

are nothing without our islands.

CURWOOD: Marshall Islands poet Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner with her poem, "Tell them".

Related links:

- More spoken word poetry by Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner

- Pacific Island Poets Use Art, Stories to Urge Climate Action at UN Conference

- The Marshall Islands Are Disappearing

- How Coral Atolls Form

[MUSIC: Dan Romer, Benh Zeitlin, “The Thing That Made You,” comp. Dan Romer, Benh Zeitlin, Beasts of the Southern Wild (Music from the Motion Picture) (Cinereach Music 2012)]

Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation and brought to you with support from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, Amber Rodriguez, and Jennifer Marquis. Thanks this week to Jennifer Stevens-Curwood. Jake Rego engineered our show, with help from Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us please on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from Trinity University Press, publisher of Moral Ground; Ethical Action for a Planet in Peril, 80 visionaries who agree with Pope Francis, climate change is a moral issue for each of us. TU Press.org, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth