April 5, 2002

Air Date: April 5, 2002

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Global Reporting Initiative

/ Cynthia GraberView the page for this story

There are standard measurements that explain a company’s financial performance. Now, a new system, sponsored in part by the United Nations, will standardize the reporting of such non-financial information as pollution emissions and labor practices. Cynthia Graber reports. (05:00)

Drop-Dead Gorgeous

View the page for this story

Cosmetics shelves are crammed with products for shiny hair and flawless skin. Cosmetic labels are crammed with chemicals and artificial preservatives. Guest host Pippin Ross talks with Kim Erickson, author of the book "Drop-Dead Gorgeous: Protecting Yourself Against the Hidden Dangers of Cosmetics." (06:00)

Animal Note: New Insect Order

/ Maggie VilligerView the page for this story

Living on Earth's Maggie Villiger reports on the discovery of six new species of insect, so different from all other known bugs that a new classification order had to be created for them. (01:20)

Almanac: Nuclear Tourism

View the page for this story

This week we have facts about an atomic tourist attraction. April marks the start of tours to a nuclear bunker in West Virginia, once meant to house the U.S. Congress in case of nuclear attack. (01:30)

Gorillas in Their Midst

/ Vicki CrokeView the page for this story

Think of mountain gorillas and the name Dian Fossey is probably not far behind. But others have devoted their lives to studying and protecting the rare primates. Now, husband and wife researchers have written of their years in the Rwandan mountains, working with, and sometimes in spite of Dian Fossey. Vicki Croke speaks with the authors of In the "Kingdom of Gorillas." (09:30)

Moss

/ Sy MontgomeryView the page for this story

When they arrive each spring they’re called the first mercies of the earth. Commentator Sy Montgomery explains the mysteries of moss. (03:00)

Rock Climbing Wrongs

View the page for this story

A new study suggests that rock climbers may damage the plants growing on cliffs. Guest host Pippin Ross speaks with researcher Michele McMillan. (03:00)

Health Note: Spain Poisoning

/ Jessica PenneyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Jessica Penney reports on a massive poisoning incident in Spain twenty years ago. (01:15)

Listener Letters

View the page for this story

This week we dip into the Living on Earth mailbag to hear what listeners have to say. (02:30)

Everglades Restoration

/ Pippin RossView the page for this story

Guest host Pippin Ross takes a look at the early planning for the congressionally mandated restoration of the Florida Everglades. The linchpin of the plan is a massive series of underground water storage tanks. (11:00)

**WEB EXTRA**

Aquifer Storage and Recovery

View the page for this story

One of the most controversial aspects of the Everglades Restoration Plan is a technology called Aquifer Storage and Recovery. Guest host Pippin Ross talks with William Logan of the National Research Council about how engineers plan to bank surface water by sending it deep underground. ()

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Pippin Ross

REPORTERS: Cynthia Graber, Lester Graham, Vicki Croke, Bob Carty

GUESTS: Kim Erickson, Michele McMillan

COMMENTATORS: Sy Montgomery

UPDATES: Maggie Villiger, Jessica Penney

[INTRO THEME MUSIC]

ROSS: From National Public Radio, this is Living on Earth. I'm Pippin Ross. A new standard for corporations with a conscience. The Global Reporting Initiative is unveiled in the shadow of Wall Street.

EITEL: The more transparency we have, the more open we are as a company, the more consumers can make their own decision.

ROSS: Also, how rock climbing can be hard on the mountainside.... A new order of insect enters the arena. All hail the Gladiator... And the nation's biggest environmental restoration project gets underway in South Florida. It's the $8 billion deal to restore the Everglades, sort of.

RICE: You can never make this system what it used to be. So, you have to figure out, how can you go back and make the system function as naturally as you can. And the only way you can do that is by engineering a system that will allow that to happen.

ROSS: Those stories this week on Living on Earth, right after this.

[NPR NEWS]

Global Reporting Initiative

ROSS: Welcome to Living on Earth. I'm Pippin Ross, sitting in for Steve Curwood. Multinational corporations have been in the spotlight in recent years. Clothing and shoemakers have been charged with doing business with sweatshops. And oil companies accused of human rights and environmental abuses. Some firms have tried to demonstrate their corporate responsibility by publishing reports detailing their social and ecological good deeds. But, there's been no standard for this reporting-until now. Living on Earth's Cynthia Graber explains.

PITYANA: There is now no great debate about the ethical duties that attach to trade and business.

GRABER: Nyameko Barney Pityana is chair of the Commission of South African Human Rights. He recently addressed a United Nations meeting of more than 250 business, finance and NGO representatives. The event: the official launch of the Global Reporting Initiative, a new set of guidelines to help quantify a company's level of social responsibility.

PITYANA: We now understand that the reckless exploitation of the natural resources, is neither political nor morally acceptable. More importantly there is now a body of opinion which affirms that such activities, ultimately, do not make business sense.

GRABER: This project was born of a partnership between the United Nations and the nonprofit group, the Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies, or CERES. The effort is touted as a standard guide for companies to use when reporting data not included in financial reports--things like energy use, pollution emissions, and compliance with international human rights standards. Robert Massie, director of CERES, says companies have become increasingly aware that their end product isn't the only thing of concern to customers and investors. For instance, the state of California now restricts its pension system from investing in countries with weak human rights records. And it's not the only one.

MASSIE: You have the city of New York pension system, a huge system, which has now and is increasingly involved in advocating that companies take steps to address climate change, and address other issues because they're concerned about the long term values.

GRABER: The report asks companies to detail such things as the amount of carbon dioxide emitted annually. Companies can list efforts to improve energy efficiency. And, there are questions about wage and labor standards. Participation in the Global Reporting Initiative is voluntary. But if a company chooses not to answer any particular question, it must explain why. The initiative is the result of input from hundreds of organizations, including activist groups like Greenpeace, financial organizations such as PriceWaterhouseCoopers, and companies such as Ford, Dow Chemical, and Nike.

EITEL: We, as a company, have learned a lot on these issues because we've been at the center of a lot of the criticism.

GRABER: Maria Eitel is vice president of Corporate Responsibility at Nike, a company that came under fire in recent years for working with overseas sweatshops. Nike admits past wrongdoing but sees its participation in the initiative as a way to demonstrate improvements.

EITEL: We have engaged in a very extensive and in-depth program to improve our labor practices and the work we do around environmental sustainability. So, the more transparency we have, the more open we are as a company, the more consumers can make their own decision.

GRABER: One thing to remember, though: this report passes no judgement on the data collected. Again, CERES director Robert Massie.

MASSIE: The sense of whether this is appropriate behavior or inappropriate behavior will be decided outside in the full-fledged sort of marketplace of debate. But it will be based on common definitions and core indicators that give you comparable information.

GRABER: But not everyone thinks the Global Reporting Initiative is an unqualified success--yet. Oxfam International, a humanitarian organization, is supporting the initiative, but it wants the process to include a way to verify a company's self-reported information. Jeremy Hobbs, Oxfam's executive director, stressed this in a speech at the lunch.

HOBBS: Whilst we have voluntary codes, we also believe that verification is a major issue which needs more work. It's fine to have voluntary codes, but if we can't see whether they're actually making a difference, then they're not terribly helpful.

GRABER: Committees are currently working out the details of how to verify a company's data. Organizers of the Global Reporting Initiative say this system is part of an ongoing process. Right now, the second draft of the guidelines is on the web for public comment and will be released in July. In addition to verification procedures, participants are also wrestling with the question of company borders. With corporations connected to so many operations around the world, how do you define where one company's responsibility ends and another's begins? For Living on Earth, I'm Cynthia Graber.

[MUSIC: Steve Roden "cycle (re-)" IN BETWEEN NOISE (Inverted Tree Projects-1993)]

Drop-Dead Gorgeous

ROSS: Lotions, gels, powders and creams can be found on cosmetic shelves all over the world. These concoctions promise to smooth wrinkles, repair damaged skin, and shave away years with a dab here, and a spritz there. But, just what's in those bottles, jars and tubes is a mystery to many consumers.

Kim Erickson is a journalist from Las Vegas, Nevada, and has written a book called "Drop-Dead Gorgeous: Protecting Yourself from the Hidden Dangers of Cosmetics." She says there are many potential hazards in the pursuit of beauty.

ERICKSON: There are number of ingredients in our cosmetics and personal care products that can cause cancer, damage your reproductive system, affect your brain, irritate your skin, or cause an allergic reaction. In fact, a number of the chemicals used in cosmetics have been labeled as hazardous by the EPA.

ROSS: This is not good news.

ERICKSON: No it's not.

ROSS: It's especially not good news because I have brought into the studio some things that I use. (Unzips makeup bag) Let's start with lipstick, something most women use. What do you have to say about lipstick?

ERICKSON: Well, surprisingly, over the course of her lifetime, a woman will eat four pounds of lipstick, which is particularly a concern since many of the artificial colors used in lipsticks, and other cosmetics, have never been tested for safety. A tiny tube of lipstick contains more artificial colors than any other cosmetics. Artificial colors are derived from coal tar, which can contain a number of nasty chemicals like benzene, naphthalene, and phenol. So, it can definitely impact your long-term health.

ROSS: Now, I have also some nail polish. I found out in your book you're not crazy about nail polish.

ERICKSON: No. You know, I've still not found a really good, safe nail polish. Conventional nail polishes, quite often, contain two chemicals which are very dubious: toluene, which is a solvent in nail polish. It's currently regulated under California's Proposition 65 as a developmental toxin. And, animal studies have shown that this chemical can cause spontaneous abortion, and can cause delayed development of the spine, learning and behavioral deficiencies in fetuses.

ROSS: So, it's not really a matter of it suffocating your living, breathing finger nail. It's really being absorbed.

ERICKSON: It is definitely being absorbed. And it systemically ends up in your bloodstream. Another chemical that's often found is formaldehyde, which is not only a suspected carcinogen and neurotoxin, but it can damage your DNA.

ROSS: In your book, you talk quite a bit about these anti-microbial soaps, which you feel are very unhealthy, which is interesting seeing as they're marketed as a health maintenance device.

ERICKSON: Yes. These anti-bacterial products have become hugely popular. But they contain biocides such as triclosan, which is a kissing cousin to a common pesticide. Animal tests have shown this chemical to be toxic to the blood, liver and kidneys. And it's also a prevalent contaminant to the environment.

ROSS: Okay. Now let's shift the conversation a little bit here to the cosmetics industry. I mean, this is sounding a little bit like the tobacco industry.

ERICKSON: There are a number of similarities. Most people believe that the U.S. FDA insures the safety of cosmetics. But they actually don't have the authority to require safety testing before a product appears on the store shelves. What's more, manufacturers aren't required to report cosmetic-related injuries, or submit safety data on the ingredients used in their products.

ROSS: Right. They just have a little warning saying it may cause a rash, or discontinue use if such and such happens. And that's all they need to do?

ERICKSON: Actually, they don't even need to do that. Some manufacturers do that because they test for short-term problems such as allergic reactions or irritations. But, by and large, manufacturers do not test for long-term health risks such as hormone disruption or cancer.

ROSS: Okay. So, what are we going to do? What do we do to be clean and pretty, and not hurt ourselves?

ERICKSON: Fortunately, there are a number of cosmetic companies out there who have become responsible. They use natural ingredients to create their products. These can be found in health food stores and online.

ROSS: And you've got some of these things with you?

ERICKSON: Yes, I do.

ROSS: Tell me what you've got.

ERICKSON: Actually, I have an anti-bacterial, waterless hand wash. And, instead of triclosan, it relies on tea tree oil, which is an essential oil, to kill bacteria and microbes. I also have a lipstick which, surprisingly, uses no FD&C colors at all. It's based on hemp and herbs.

ROSS: Now, you have some amazing recipes in your book for making things like skin smoothers and even perfume. Do you have any recipes that are for extremely busy people?

ERICKSON: Actually, there are some recipes which are extremely easy and quick to make. One of them is a gentle exfoliant for your face. It's an oatmeal and honey mask. All you do is you mix a half a cup of oatmeal with two tablespoons of honey, slather it on, put your feet up, rinse it after about 20 minutes with warm water, and you have a glowing complexion.

ROSS: Hey, rinse it. Let your dog lick it off.

ERICKSON: That's true. It certainly wouldn't hurt the dog.

ROSS: Kim Erickson is a freelance environmental journalist in Las Vegas, Nevada, and author of "Drop Dead Gorgeous: Protecting Yourself from the Hidden Dangers of Cosmetics." Kim, thanks for talking with me today.

ERICKSON: It's my pleasure, Pippin.

Related link:

Drop-Dead Gorgeous from Amazon.com.">

Animal Note: New Insect Order

ROSS: Coming up, two wide-eyed biologists venture into the kingdom of the mountain gorillas. First, this page from the Animal Notebook with Maggie Villiger.

[THEME MUSIC]

VILLIGER: Entomologists may be smiling, but entomophobics are cringing. That's because scientists have announced the discovery of several brand new species of bugs that are so unusual, a new insect order had to be created to classify them. The order is called Mantophasmatodea. And the first representative is a 40 million year old fossil encased in amber.

"The Gladiator"

"The Gladiator" (Photo: Piotr Naskrecki)

But researchers have also located members of five more Mantophasmatodea species that are actually creeping and crawling this very day in the remote Brandberg Mountains of Namibia in Southern Africa. Scientists call the discovery analogous to finding a living saber tooth tiger, or a woolly mammoth roaming some remote region. Entomologists say these newfound bugs are a sort of cross between a praying mantis and a walking stick, with powerful spiny legs that they use to grab and crush their prey. The carnivores are so voracious, some captured bugs were eaten by their companions on a trip back to Germany with the scientists. That might explain why the bugs have been nicknamed "gladiators."

The "gladiator" insect was found in the

The "gladiator" insect was found in theBrandberg Mountains of central Namibia.

(Photo: Piotr Naskrecki)

Researchers are setting up colonies in captivity to observe the way these insects feed, breed and develop. And conservationists hope to set aside the insect habitat as a protected biosphere reserve. That's this week's Animal Note. I'm Maggie Villiger.

ROSS: And you're listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Jali Kunda "Spring Waterfall" GRIOTS OF WEST AFRICA & BEYOND (ellypsis- 1996)]

Almanac: Nuclear Tourism

ROSS: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I'm Pippin Ross.

[MUSIC: Vera Lynn "We'll Meet Again" DR. STRANGELOVE]

ROSS: It's finally April when spring really begins. More daylight, less cold. The start of baseball. The end of March madness. And of course, the kickoff of atomic tourism season. It all takes place 700 feet below the swanky Greenbrier Resort in White Sulfur Springs, West Virginia, behind 25 ton doors, past miles of concrete corridors, in a bunker created to house the U.S. Congress in case of nuclear war. Dubbed "Project Casper," the bunker was built for 14 million dollars in the 1950's and remained hush-hush until The Washington Post exposed the hideaway in a 1992 article.

(Photo courtesy of The Greenbrier)

(Photo courtesy of The Greenbrier)Though the Greenbrier is a five-star resort, the bunker is no paradise. It's equipped with decontamination showers, an isolation chamber, and a pathological waste incinerator. The facility also contains mini-replicas of the House and Senate Chambers, even down to the oil paintings of the founding fathers on the walls. And, to communicate with the outside world, a television studio complete with a faux Washington, D.C. backdrop.

(Photo courtesy of The Greenbrier)

(Photo courtesy of The Greenbrier)Today, the bunker is rented for tours and special events. James Bond parties, we're told, are a favorite theme. About 20 such gatherings happen each year in the subterranean wonderland, featuring 1950's costumes, big bands, dancing and cocktails. Care for another martini, Dr. Strangelove? I'll take mine shaken, not stirred. And for this week, that's the Living on Earth Almanac.

[MUSIC FADES]

Gorillas in Their Midst

ROSS: In 1978, Peace Corps volunteers Bill Weber and Amy Vedder took off on, what they thought would be, the adventure of a lifetime. The two biologists were headed for the Volcanoes National Park in Rwanda to study mountain gorillas with, none other than, Dian Fossey, the world's most famous gorilla expert.

But when Weber and Vedder reached Rwanda, they found a gorilla population in trouble. And an even more troubled Dian Fossey. Their experiences are chronicled in the book "In the Kingdom of Gorillas." Vicky Croke spoke with the authors and prepared this report.

CROKE: For Amy Vedder, learning "gorilla" has been pretty easy. Almost from the beginning of her time in the Rwandan rainforest, she found she could mimic the massive animals who are, in general, very quiet. There is the deep and deeply happy belch of contentment, for instance.

VEDDER: And it goes [gorilla sounds].

CROKE: And the irritated, cough-like bark that serves as a warning.

VEDDER: [gorilla sounds].

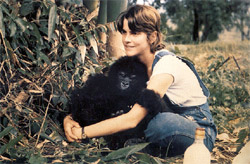

Amy and Mweza. (Photo: WCS/Amy Vedder)

Amy and Mweza. (Photo: WCS/Amy Vedder)CROKE: Moments spent with the gorillas in the field were idyllic, but all too short. Whether they were rescuing the sick and orphaned, or carving out a safe place for all mountain gorillas, Vedder and Weber have truly battled the odds, finding opposition in some surprising places.

One of the first cases they took on was that of little Mweza who, in February of 1978, was taken from her family group by poachers. By the time the biologists reached the emaciated four year old gorilla, the wound from a wire noose around her ankle had turned gangrenous. They moved her to camp, and for eight days, nursed her round the clock.

VEDDER: We were just incredibly frustrated by the fact that there was no adequate treatment for an ill gorilla. There was help waiting down the mountain in the form of human doctors. But that help was being refused by Dian. And it was a terribly, terribly frustrating situation, to know there was a gorilla that might be able to be saved and there was no way to do it. And we watched her die a horrible death. And that, I think, was a really galvanizing point in our life, feeling that research was one thing, but we had to move as quickly as we could to action to try to save these animals.

CROKE: Vedder and Weber were seeing a deeply troubled Fossey, a woman far different than the one gracing the airwaves through National Geographic specials; a far darker personality than that eventually brought to life in the movie, Gorillas in the Mist.

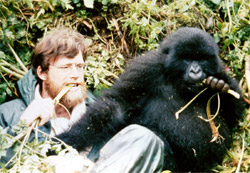

Both Bill and his gorilla companion enjoy celery.

Both Bill and his gorilla companion enjoy celery.(Photo: WCS/Amy Vedder)

WEBER: By the time we came to know Dian, in the late '70s, she was probably a very different person than the woman who first came to Rwanda in 1967. And, I think a lot of alcohol, isolation, perhaps difficulty dealing with the fame that had been dropped on her, I think pushed her into mental illness. And I think it's difficult to sit back and judge someone and say "they're wrong, they're bad," when in fact what you're looking at is someone who is sick.

CROKE: The couple began to look at the big picture of conservation. But Fossey would have none of it, ultimately rejecting every proposal the two young field biologists brought forward. Primatologist Michele Goldsmith, a National Geographic scientist and a professor at the Tufts University Vet School, has also pondered Fossey's decline.

GOLDSMITH: I think that she was a perfectionist, and that this got in the way of her efforts and her daily frustration in trying to save the gorillas. I'm not sure if that's what led her to be an alcoholic. And I'm not sure what effect being an alcoholic actually had.

CROKE: But the effects were clear to Amy Vedder and Bill Weber. They realized they were on their own. Vedder was studying gorilla ecology to better understand what these animals ate, and how much of it they needed to survive. And Bill Weber was intrigued by the human part of the equation. How do you get desperately poor local people to care about the conservation of these wild animals?

WEBER: To be truly effective, you also have to learn about local culture, politics, economics. You have to go out and become a bio-diplomat, an advocate for their protection. And to do that often means leaving the park, going out and working with local villagers, getting to know government officials, whatever you may think of them, and trying to influence their thinking and their decision making so that they take actions in favor of conservation. In this case, to protect the gorillas.

CROKE: So, armed with some basic knowledge, the couple hatched a plan. Though the word "eco-tourism" hadn't yet been coined, the two biologists plumbed the concept in a bid to stave off government plans to make commercial use of the park for cattle ranching. Vedder and Weber claim they had a way to earn more money for the park. But, how could they be so confident that it would work?

WEBER: We invented the numbers. We knew how much they were estimating for revenue for the cattle project. And we came up with a higher number--3000 tourists, 25 dollars a day, apiece. That's 75,000 dollars. Bingo, we win.

CROKE: Wild gorillas have a tendency to run from the sight of human beings, even eco-tourists with deep pockets. So, Bill Weber hustled to habituate a group, training the gorillas to tolerate the visits from paying strangers. And, they had to habituate humans to the presence of gorillas. Here, in a scene from a National Geographic documentary, Amy Vedder quietly instructs a group of tourists about the etiquette of entering gorilla society.

[SOUND OF LEAVES AND BIRDS CHIRPING ON TAPE]

VEDDER: [Whispering] No real problem today. But we should stay close together. And we should speak quietly. And make sure--you're going to be excited--but be careful. Carry your sticks close to your bodies.

CROKE: When the couple first came to the park, visitors brought in a meager $7,000 annually. But by 1989, with the Mountain Gorilla Project in full swing, the park was making a million dollars a year. However, Tufts primatologist Michelle Goldsmith says, eco-tourism has been a double-edge sword for gorillas. They can catch human diseases. And, habituated gorillas tend to leave the safety of their park. But Goldsmith has no doubt about one thing.

GOLDSMITH: About 20 years ago, this population was being devastated by poachers and habitat disturbance. And, without the creation of tourism at that time, I think that we probably would have lost the entire population.

CROKE: In the late '80s, with the future of gorillas seemingly assured, Bill Weber and Amy Vedder returned to the United States where they're now both directors of the Wildlife Conservation Society. The rescue of this fragile population would be a sweet ending to the couple's shared story with gorillas. But history has added a few more unexpected chapters. As Amy Vedder continued to visit Rwanda in the early '90s, she saw signs of, what eventually would become, the brutal genocide of the Tutsi minority there.

VEDDER: We saw a downward spiral. But never expected the kind of explosion that took place in 1994 when the genocide and the cataclysmic war broke out.

CROKE: In the course of 100 days, perhaps 800,000 Tutsi were killed.

WEBER: Turning those numbers into something personal was difficult. There are many people we worked with who are lost or disappeared. The one probably closest to us was Clementine.

CROKE: The nanny to their two children, a woman they considered a close friend, disappeared during the genocide. Amy Vedder again returned to Rwanda and tried to find her. The emotion of that time is still raw.

VEDDER: When I returned, I did look up her house and her family. I showed a picture of Clementine to her sister, who thought that that meant she was alive.

CROKE: Despite the fact that Clementine has never been heard from, Vedder and Weber find solace in one astonishing fact.

WEBER: The gorilla numbers have actually continued to increase from a low of 260 twenty years ago. The latest numbers from those working in the park, and particularly the guards who, at considerable risk, are going out and monitoring the gorillas, have come up with their best guess of around 355 gorillas.

CROKE: Gorillas are slow breeders. And a net increase of 95 over two decades is fantastic, especially considering the turmoil churning around these animals. Tourists weren't rushing back. But Amy Vedder felt compelled to. With the loss of so many of her friends, there will always be, for her, an unspeakable agony associated with her beloved land. And yet, there is also joy. When Vedder returned to Africa last year, one miraculous reunion awaited her.

VEDDER: I went back to see Pablo who, when I had left the research group, group five, he was the juvenile delinquent, four and a half year old who was always getting in trouble, pulling on our backpacks, causing all sorts of problems. And here he was a huge silverback. A massive animal. Still a little slack-jawed, like he used to be. He's still slightly crossed eyes, like he used to have. But here he was--the dominant silverback in a group of 44 animals in his family, the largest group ever known for gorillas. So, it was a really optimistic moment for me to see him in charge of this new family.

[GORILLA SOUNDS AND FOREST NOISES: Bernie Krause "Dian's Family" DREAMS OF GAIA/AFRICAN ADVENTURES (EarthEar-1999)]

CROKE: The mountain gorillas of Rwanda survive in their tender and tenuous Eden, a place blessed by the hard work of two idealistic and tireless conservationists, and the commitment of the Rwandan people. For Living on Earth, I'm Vicky Croke.

[GORILLA SOUNDS FADE]

Related link:

In the Kingdom of Gorillas from Amazon.com.">

Moss

ROSS: The 18th century British art critic, John Ruskin, called them the "first mercy of the earth." He was talking about mosses. And commentator Sy Montgomery urges you to explore their velvet tapestries for the first signs of spring, and to see in them how humility mingles with strength.

MONTGOMERY: They bask in frigid snowmelt, like a sunbather soaks up rays on a beach. Before the ferns uncoil, before the tree buds burst, before the jack in the pulpit thrusts through the ice, tiny mosses glow green.

Mosses fulfill the prophecy that the meek shall inherit the earth. At the first stroke of spring, the world is theirs. Yet, those of us who don't know better pass by these lovely plants. Maybe that's because mosses are small. Most grow only one-sixteenth of an inch to a few inches tall. And they tend to hide in humble places, between the cracks in sidewalks, in the crevices of tree bark, on the underside of rocks.

Their common name suggests their staggering variety of forms. The humpbacked elves, for instance, are mushroom-like, greenish-black mosses. Knight's plume has light yellow-green feather-like leaves that clothe decaying logs. Names are fanciful. But mosses are disarmingly simple. They're a bunch of tiny, leafy stems, growing so closely together, they form velvety cushions. That's it. They have no roots. They have no flowers. They don't make seeds, but reproduce by spores.

But because their needs are simple, mosses can grow in alpine and arctic wastes, on bare cliffs, on Main Street, in jungles, in backyards, in bogs. Some grow on bones, on feces, on corpses. One species, naturally luminous, glows in the dark of caves. As one writer observed, "They serve as pioneers, carrying life where it could not otherwise be."

This ability to colonize areas too difficult for other plants suggests mosses may have been among the earliest creatures to venture from water to land. They don't fossilize well. So, no one really knows how or when mosses evolved. But one feels something primal about them, a connection to the creation.

Surely, the landscapers of Japan's Buddhist temples knew the value of mosses for soothing the human spirit. There's a temple in Kyoto famous for its five acre garden, filled with too many varieties of mosses to mention here. What better aid to meditation than this simple, ancient, lush blessing. Inviting us to look closely, think deeply, and remember that earth's meekest creatures promise us spring.

[MUSIC: Rolling Stones "Waiting On a Friend"]

ROSS: Commentator Sy Montgomery is author of the new book "Encantado: Pink Dolphin of the Amazon." You're listening to NPR's Living on Earth.

Rock Climbing Wrongs

ROSS: A new report says rock climbers have a big impact on the plant life that grows on the cliffs they climb. Michele McMillan is a graduate student at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, who did the research. Michele, how did you figure this all out?

McMILLAN: I actually looked at 25 climbing routes and 25 unclimbed areas. And I would actually tie on at the top of the cliff, and I would lower myself over the edge. And then I would dangle from the rope for, sometimes, hours at a time.

ROSS: And you found?

McMILLAN: Well, I looked at the number of plants that were present in climbed versus unclimbed areas, and I found that much lower numbers were present in climbed areas than in unclimbed areas. And, I also found that there was actually a change in the types of species that were present. So I had 81 percent of all of the plants that I found in climbed areas where alien species to Ontario were only 27 percent of the plants in the unclimbed areas were aliens.

ROSS: So, what does that mean? I mean, how are these non-native species getting in there?

McMILLAN: Well, a couple of things need to happen for the alien species to get into an area. And the one is that there has to be room for them. So, climbers are making room for the alien species simply by reducing the numbers of plants that are present. And then, the second thing that needs to happen is there needs to be some sort of seed or propagule from the plant introduced to the area. And, a good way for that to happen is in the soil on climbers' shoes, or attached to climbers' coats or gear. Or, they can come in on the wind.

ROSS: Now, have you found yourself kind of scowling at climbers?

McMILLAN: Not at all. I want to make it clear that I am not anti-climbing, and I am not anti-climbers at all. I think that climbing can definitely occur in an area with as little impact as possible.

ROSS: And so, that would kind of imply that rock climbers have some responsibility to do what?

McMILLAN: One thing that I suggest rock climbers do is that they stick to currently established climbing routes rather than establishing new routes.

ROSS: Oh, they hate that.

McMILLAN: I know. Climbers do love to be the first one to ascend a climb. But I would ask that climbers just climb where there's already climbing occurring. And there's a couple of other things. There are trees that are hundreds of years old. And some have been found that are over a thousand years old. Obviously, I would ask that climbers don't cut down branches to improve a climb. Another thing that climbers do sometimes, especially when they're establishing a new climb, is that they wire brush or blowtorch mosses and lichens off the rock.

ROSS: No.

McMILLAN: Yeah. It is true. So, I would ask that you just avoid using those finger or toeholds if you find them too slippery, and just try to look for another one.

ROSS: Michelle McMillan is a graduate student at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada. Thank you very much, Michelle. And keep up the good work.

McMILLAN: Thank you very much. Take care.

[MUSIC: Neil Diamond "Love On the Rocks"]

Health Note: Spain Poisoning

ROSS: Just ahead, your letters and comments. First, this Environmental Health Note from Jessica Penney.

[THEME MUSIC]

PENNEY: In 1981, thousands of people near Madrid came down with severe cases of debilitating muscle pain, rashes and respiratory failure. More than 20,000 people fell ill to the mysterious syndrome and nearly 500 died. Some people thought the disease may have come from pesticides on tomatoes. Others believed cats and dogs spread it. And many people killed their pets as a result.

But, a just released report from the World Health Organization confirms the cause of the disease to be an industrial lubricant made from rapeseeds that was illegally sold as olive oil. The disease is now known as Toxic Oil Syndrome.

The WHO report on the incident says that up to 80% of the victims are still crippled by lung problems, muscle pain, and hardening of the joints and skin. It also suggests that a unique set of circumstances led to the epidemic. The researchers believe that the lethal oil contains a particular toxin that formed during the refining process. And they think the poison causes its victims immune systems to attack their own bodies.

None of the makers of the oil had to pay fines for their actions. But five years ago, the Spanish government was found guilty of lax regulation. And victims were awarded about $2 billion in compensation. That's this week's Health Note. I'm Jessica Penney.

ROSS: And you're listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: David Rothenberg "In the Rainforest" SUDDEN MUSIC (Mysterious Mountain Music-2002)]

Listener Letters

ROSS: It's Living on Earth. I'm Pippin Ross. How to make the River of Grass flow once more. The restoration of The Everglades is just ahead. But first:

[THEME MUSIC]

ROSS: Time for comments from our listeners. New Hampshire Public Radio listener Charles Terry heard our story about geocaching enthusiasts, who zero in on mini- treasure troves with the help of handheld Global Positioning System units.

"Geocaching was not born after Clinton lifted the GPS ban, as your story stated, " Mr. Terry writes. "It has been popular in Great Britain for quite some time now. Only there, it's called 'letter boxing,' an orienteering sport done with a hand compass and a topographic map. The prize is not some trinket, but the privilege to stamp your logo in a book kept in a metal tube as a sign to other seekers that you found the cache. Walking around trinket trading with a device that tells you exactly where you are is a no-brainer, and just seems so, well, American."

Our story about dilute amounts of pharmaceuticals and personal care products detected in waterways left some listeners with a lingering question. "Your report ended with, 'don't dispose of unwanted drugs down the drain or toilet,'" wrote WBEZ listener Vic Banks in Chicago. "Hey, finish up reporting by telling us what to do with the stuff."

Okay. Here's some suggestions from the folks at the U.S. Geological Survey. They say to discard old drugs as hazardous waste. Most communities designate times when they'll accept things like old paint and cleaning products for disposal. And your local pharmacy may accept expired or unwanted drugs for incineration.

And finally, about our EarthEar recording of migrating geese on a stopover in North Dakota, "Did you check their passports?", asked KQED listener Marc Spear from San Francisco. "I'm curious to know how you were able to tell that the geese, whose vocalizations you broadcast, were Canadian. They could have been American geese traveling to Canada for the summer. Nationality aside, I think you meant to refer to the species 'Canada Geese.'" Mr. Spear is right. The birds, of course, were Canada geese.

We'll take your corrections or kudos on our Listener Line any time at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-9988. Or write to us at 8 Story Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138. Our email address is letters@loe.org. Again, that's letters@loe.org. And, visit our web page at www.loe.org. That's www.loe.org.

Everglades Restoration

[ENGINE STARTING]

ROSS: The only way to really see Florida's Everglades is aboard an airboat. These flat bottomed sardine cans slice through naturally formed canals, flanked by waving sawgrass, and peppered with little islands. There's no place like it in the world.

[SOUND OF BIRDS]

ROSS: The Everglades used to function as a nearly perfect system to store, filter and distribute water throughout South Florida. It was a system able to readily adjust to the region's dry and wet seasons. But, today's Everglades are nothing like the place Miccosukee Tribal Elder, Buffalo Turtle, says he grew up in.

TURTLE: If you're going to find a fish, you will find them. Because you can look down, and you can see the bottom. The water is very clean. And all those that birds used to be around. It's gone. Everything, it changed so quickly. Just seems like it's overnight.

ROSS: Well, not quite overnight. The reshaping of the Everglades began in the late fifties. The architect was Napoleon Bonaparte Broward. He was Florida's Governor at the time. And his plan was to drain the four million acre swamp.

[SOUND FROM WATERS OF DESTINY]

MAN: Foot by foot, mile by mile, the work went on. Drilling, blasting, digging, bite by bite. Five to eight cubic yards per mouthful. Slowly, persistently, gouging the bottom to build up the top.

ROSS: This archival film, Waters of Destiny, documents the efforts to dry up the Everglades. The Army Corps of Engineers built 1,800 miles of levies and canals to keep new housing developments and farmland from being flooded. The water was diverted to people and crops.

MAN: Water that once ran wild, water that ruined the rich terrain, water that took lives and land, put disaster in the headlines, and death upon the soil. Now, it just waits there, calm, peaceful, ready to do the bidding of man and his machine.

ROSS: It was a huge engineering success. But it left the Everglades crisscrossed with roads and canals, and no longer able to serve as the region's giant water filter. Terry Rice used to command the Army Corps of Engineers in Florida.

RICE: You can look at the EPA records. They republish a report every two years on water bodies in Florida. Almost all of them are degrading in water quality, year by year. People don't understand that. People don't know that. I mean, we know it because that's our job to know it.

ROSS: The decline of the Everglades so upset the Miccosukee Tribe, it filed suit after suit, blaming the state of Florida for the deteriorating water quality. Tribal chairman, Billy Cypress.

CYPRESS: I make it short and simple. And I hope it's sweet. And I hope people will listen, think about it twice: commitment. Get it going. And I hope we have enough attorneys that will sue and sue and sue and sue until we get it corrected.

ROSS: So, the Miccosukees sued. Environmental groups lobbied, and eventually, Congress passed what's called "The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan." With an eight billion dollar price tag, it's the biggest government funded environmental project in history. But, Army Corps of Engineers, Colonel Terry Rice, now an advisor to the Miccosukee Tribe, says "restoration" is a bit of a misnomer.

RICE: You can never make this system what it used to be. So, you have to figure out, how can you go back and make the system function as naturally as you can? And the only way you can do that is by engineering a system that will allow that to happen.

ROSS: One step is to undo some of what was done in the '50s, like taking out canals, tearing up roads, and letting rains once again flood the land. The goal is to recreate a hundred mile path of undisturbed water flow from Lake Okeechobee to the Florida Keys. But, the deconstruction project will take decades. And, it doesn't include the thousands of acres of Everglades already destroyed, or now inhabited by people and farms.

ZEBUTH: There is a saying that there are three things wrong with the Everglades' system. We need more storage. We need more storage. And we need more storage. Because that is what we have primarily destroyed.

ROSS: Herb Zebuth is a water specialist with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. He stands at the shore of Lake Okeechobee. This lake used to feed tons of fresh water into the ecosystem. And when it was healthy, the Everglades acted like a sponge, mopping up the lake's overflow in the rainy season and holding water during the dry season.

But, right now, the Everglades can't soak up the overflow. When the rains come and the lake floods, the Glades drown in polluted runoff. And the water it can no longer hold flows out to sea. In the dry season, Lake Okeechobee water goes to people and farms, and the Everglades goes dry.

ZEBUTH: Now, because we drained off half of the Everglades, and we've lowered our water table so a cheap development could come in, we are dependent more and more and more on Lake Okeechobee as a water supply when, naturally, it didn't have to meet those needs. And that's why we're finding that, more and more often, we're falling short.

ROSS: The quick fix is a two billion dollar project to install more than 300 deep wells near Lake Okeechobee to capture and store water during the rainy season and send most of it to the Everglades during the dry season. It's a controversial idea. But, Zebuth says, the only other option is to build massive above-ground reservoirs, flooding now valuable land.

ZEBUTH: So, putting it underground eliminates those pressures. I mean, you don't have to scrounge around trying to find land that's too politically hot to buy. Plus, you won't lose some of that water through evaporation, which is a great part of our loss here in Florida.

ROSS: Deep well technology is used in other parts of the country. But, the one plan for the Everglades is 20 times the size of the largest existing system. And, some South Floridians worry that too many hopes are being hung on a technology that's never operated at such a massive scale.

Scientists, appointed by Congress to inspect the restoration project, agree the wells are still too experimental to play such a critical role in restoring the ecosystem. Meanwhile, environmental activists like Alan Fargo of Florida's Sierra Club worry about the long-term effects.

FARGO: I believe the technologies like aquifer storage and recovery are going to come back to haunt us, and could render parts of South Florida uninhabitable. And for the people who live in areas effected by contaminated water, we're talking about a new misery quotient for life in Florida.

ROSS: To avoid contaminating the aquifer, officials say water will be filtered before it's pumped into the ground. But even that precaution isn't fail-safe. William Logan is on the Water Science and Technology Board of The National Research Council, and has worked on pilot projects underway in Florida. He says when you store water underground in oxygen depleted environments, you can change its composition. And when you bring that water back to the surface, it may return with some unwanted chemicals.

LOGAN: Whether we're talking about mercury, or whether we're talking about arsenic or heavy metals, it's something that has to be tested. I think that is the argument that many people would be making here.

ROSS: Even proponents of the storage wells admit there are risks. But, Broward County Water Management District Director Roy Reynolds, says if the deep well system can restore water flow to the Everglades, it'll be the environmental coup of the century.

REYNOLDS: But there are some major questions, major questions about what may happen when we put water under the ground on such a large scale. That's why we need to move forward rapidly with the pilot projects, especially the pilot projects around Lake Okeechobee.

[LOUD SPEAKER]

ROSS: Reynolds is attending a strategy session of the South Florida Water Management Board. Representatives from some 500 divergent groups are here trying to reach consensus on a 68-part plan to revive the Everglades quickly. The group is made up of natural adversaries: the sugar industry, trying to hold on to its acreage; developers, who want more land; and, environmentalists who would like as much of the Everglades restored as possible. Reynolds says, the money is available. The crisis is real. And, dickering is simply no longer an option.

REYNOLDS: We've never all come together in agreeing 100 percent, 100 percent of the time. But I think we all realize that if we don't get it right, we're all going to suffer. If it goes wrong for one side, it's likely to go wrong for all of us. And there's a lot of folks sitting around this table that recognize that.

ROSS: Roy Rogers is senior vice president of the Arvida Corporation, one of Florida's biggest developers. He's standing at the edge of a vast bird-filled swamp, smack dab in the middle of an upscale housing development.

ROGERS: Some people would look at this, and think it's an unmade bed. It just doesn't look right. It's not tailored.

ROSS: Under pressure from environmental groups, The Arvida Corporation set aside thousands of acres of wetlands inside its 10,000 acre development that abuts the Everglades. Rogers says it turns out the wetlands improve the development's water supply, and attract wildlife. In the end, he says, Everglades preservation is a smart business policy.

ROGERS: The doomsday situation is that we don't have enough water, that we kill the Everglades, that we spoil the estuary system that rings our waters, that the coral reefs snuff out, that it's a loathsome place for tourists to come to. The economy takes a tubing. And no one wants to live here because it's a place of horror. You've taken a paradise and turned it into a horror. We can't allow that to happen.

ROSS: The entire Everglades restoration project could take as many as 30 years to complete. By that time, Florida's population, and the demands on the state's water supply, is expected to double.

[MUSIC: TUU "Pan American" ONE THOUSAND YEARS (WaveForm-2001)]

**WEB EXTRA**

Aquifer Storage and Recovery

(Audio Only)

ROSS: And for this week, that's Living on Earth. Coming up next week, what makes us human? Repeated breakthroughs in medical technology are revolutionizing medicine. But, are they changing who we are as human beings? Living on Earth's five-part series Generation Next: Remaking the Human Race explores this subject, starting next week. And its producer Bob Carty joins me now from San Diego. Hi, Bob.

CARTY: Hi, Pippin.

ROSS: What inspired you to take on this series?

CARTY: Well, it's because there's a number of new technologies that have the potential to change how we evolve as a species; how we design our babies, for example; how we might change our intellectual or physical capacities; how we can put animal parts inside our bodies; or how we might be able to meld our minds with computers and machines, become cyborgs. These are, in a sense, exciting but also terrifying technologies that deserve really serious examination.

ROSS: What sorts of technologies are we going to be hearing about?

CARTY: Well, the series looks at the cloning debate, both the therapeutic cloning and the reproductive cloning issues. We're going to look at genetic therapy. But also, that kind of gene therapy that's called "germ line manipulation," which could change generations to come. And, we'll look at the issue of marriages between machines and human beings, cyborgs, if you want. And, the series begins, though, with this look at xeno-transplantation technology.

ROSS: Xeno-transplantation. Can you explain that?

CARTY: Well, xeno is the Greek work for "foreign," of course. And what it means is, basically, putting foreign species into our bodies. In many cases, they're thinking of using pig cells, or pig organs. And, that has great potential, Pippin, because it could end the tragedy of so many people who die on waiting lists, as they're waiting for human organ transplants. Unfortunately, though, the technology, though it has great promise, also has some great risks.

ROSS: What exactly are those risks?

CARTY: Well, the risks that most experts have pointed to is the fear that transplanting a pig organ, or cell, into a human being could transfer some of the pig diseases to humans and, actually, set off a whole new pandemic, a contagion around the world. And that's a concern that one of my guests raises. He's Robin Weiss. I have a little bit of tape from him. He's a virologist at the University College of London, England. And here's what he has to say about the risks of xeno-transplantation.

WEISS: The worst case scenario is that we'd set off something like a new AIDS epidemic. That a pig virus would become established in a human population, be a killer virus, and would start to spread.

CARTY: And, that was Robin Weiss of University College of England, Pippin.

ROSS: Well, thank you, Bob. And, I'm looking forward to hearing it.

CARTY: Okay. You're welcome.

ROSS: Bob Carty is a producer with CBC Radio's The Sunday Edition, and his series Generation Next starts next week on Living on Earth, and will air once a month through August.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

ROSS: We leave you this week with a serenade featuring creatures of the Everglades. Among them, a tufted titmouse, a white-eyed vireo, a northern cardinal, a red-bellied woodpecker, and an American crow, supported by a backup chorus of cicadas and frogs. Lang Elliott was there with his recording equipment as the sun rose above the Big Cypress Preserve.

[BIRDS]

ROSS: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. Our staff includes Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Jennifer Chu, Gernot Wagner, along with Peter Shaw, Leah Brown, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson, and Milisa Muñiz. Special thanks to Ernie Silver. We had help this week from Rachel Girshik and Jessie Fenn. Alison Dean composed our themes. Environmental Sound Art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our technical director is Dennis Foley. Ingrid Lobet heads our western bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor. Chris Ballman is the senior producer. And Steve Curwood is the executive producer of Living on Earth.

I'm Pippin Ross. Thanks for listening.

FEMALE ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation for coverage of western issues, The National Science Foundation, supporting environmental education, and The Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living on Earth's expanded internet service.

MALE ANNOUNCER: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth