May 3, 2002

Air Date: May 3, 2002

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Farm Bill

/ Anna Solomon-GreenbaumView the page for this story

As Congress puts the final touches on a new Farm Bill, some lawmakers are calling it a victory for conservation. Living on Earth’s Anna Solomon-Greenbaum talks with host Steve Curwood about why small farmers and environmental groups disagree. (05:30)

Wing Dams

/ Lester GrahamView the page for this story

The Great Lakes Radio Consortium’s Lester Graham reports on a study that raises questions about the Army Corps of Engineers’ use of so-called wing dams to control rising waters during floods. (06:00)

Department A/Tech Note

/ Cynthia GraberView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Cynthia Graber reports on a new technique to control rats from afar with possible future use in search and rescue missions. (01:20)

The Living on Earth Almanac

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about refrigeration. In 1851, a doctor gave up his medical career and received a patent for a prototype of mechanical refrigeration. (01:30)

Myopia

View the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood speaks with evolutionary biologist Loren Cordain. Cordain's recent paper suggests that diets high in starchy food may lead to near-sightedness. (04:40)

Listener Letters

View the page for this story

This week we dip into the Living on Earth mailbag to hear what listeners have to say. (02:00)

Life With Abbey

/ Paul InglesView the page for this story

Author Jack Loeffler chronicles his friendship with the late writer Edward Abbey in the book "Adventures with Ed: A Portrait of Abbey." Paul Ingles reports. (06:30)

News Follow-up

View the page for this story

New developments in stories we’ve been following recently. (03:00)

Department B/Health Note

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on the use of satellite technology to predict disease outbreaks in Africa. (01:15)

Fish Out of Water

/ Nancy CohenView the page for this story

According to the Palmer Drought Index, one-quarter of the nation is in a severe drought. Some states are asking citizens to curb their water use. And in the west, many states are on fire-alert. All over the country, rivers and lakes are at abnormally low levels. As Nancy Cohen reports from Connecticut, both fish--and those who catch them--are affected by the dry conditions. (06:15)

The Elusive Eel

View the page for this story

Author Richard Schweid traveled the world in search of the mysterious and much-sought-after delicacy of the eel. Host Steve Curwood talks with Schweid about the fruits of this search, and about his new book, "Consider the Eel". (08:45)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

REPORTERS: Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Lester Graham, Paul Ingles, Nancy Cohen

GUESTS: Loren Cordain, Richard Schweid

UPDATES: Cynthia Graber, Diane Toomey

[INTRO THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From National Public Radio, it’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. One of the most important environmental laws to come out of the U.S. Congress this year is the farm bill. Folks are divided about the impact.

HARKIN: We have increased conservation more than any farm bill in history, almost an 80 percent increase in our conservation programs.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: The new commodity title in this farm bill alone could be considered one of the biggest anti-environmental bills passed in recent years.

CURWOOD: The environment and the farm bill. Also, fish out of water: how drought can affect aquatic populations. And the mysteries, the markets, and the savory morsels of that most snake-like of fish, the eel.

SCHWEID: They’re quite tasty, like a slightly grainy pasta, with a tiny crunch from the backbone, and a faint after-taste of fish and garlic.

CURWOOD: Mm, good. We consider the eel and more this week on Living on Earth, right after this.

(NPR NEWSCAST)

[THEME MUSIC]

Farm Bill

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Congress is putting the final touches on a new farm bill. The last bill was crafted in 1996 and was dubbed "Freedom to Farm." It was designed to wean farmers off government payments, but low crop prices resulted in emergency bailouts and sent lawmakers back to the drawing board. What they came up with looks pretty much like the pre-reform, subsidy-laden farm bill, but it also contains some increases for conservation programs. Living on Earth’s Anna Solomon-Greenbaum joins me now from Washington. Anna, lawmakers were promising that this new farm bill could be the first major piece of environmental legislation of the 21st century. How did it turn out?

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Well Steve, many of those lawmakers are still calling it that. This bill takes more land out of production and it adds acres for wildlife habitat. It increases payments to help farmers deal with pollution, and it also adds two new conservation programs: one that would protect grassland, another that pays farmers for good stewardship on land that’s still in production. This plan came from the chair of the Senate Ag Committee, Tom Harkin of Iowa. Here he is touting the bill at a recent press conference:

HARKIN: In this bill we have increased conservation more than any farm bill in history, almost an 80 percent increase in our conservation programs.

CURWOOD: So, based on what Senator Harkin is saying, I’m assuming that environmental groups are pleased with how this bill turned out.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Well, you might think that but they say the money that’s going into conservation is still far below what’s needed to reach all the farmers who want to do conservation work on their land. There’s a huge backlog for these programs. Particularly small farmers and those who don’t grow the kinds of crops that entitle them to subsidies; often, conservation money is the only help they can get from the federal government. Meanwhile, the vast majority of the money in this bill is still going to the biggest, wealthiest growers of staple crops. These are commodity crops like corn, cotton, sugar, wheat. Suzanne Fleek, with the Environmental Working Group, told me the new commodity title alone could be considered one of the biggest anti-environmental bills passed in recent years.

FLEEK: By eliminating key reforms to reduce subsidy payments to the largest agri-business, and still allowing farmers to crop new land, will mean that acres and acres of wildlife habitat, grasslands and wetlands will be converted to commodity crop production, increased use of fertilizers and herbicides that eventually will get into everyone’s rivers, lakes, and drinking water.

CURWOOD: Anna, I need you to clarify something here. I thought there was one program in the bill that’s meant to deal with water pollution problems. What happened to that?

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Well, you’re right, and I think you’re talking about the Environmental Quality Incentives Program, or EQUIP. The worry there, again, is that the program seems to have been co-opted by some of the biggest corporate livestock producers. A lot of the small farmers and environmental groups say the payment limit’s been set so high in this bill— it’s going from $50,000 in the current bill to $450,000 in the new one— that companies like Smithfield and Cargill are going to be able to use this program to help them comply with laws like the Clean Water Act that some people argue that they should be able to meet on their own. Industry argues that conservation money shouldn’t be available for some and not for others. This is Dave Salmonsen. He’s with the American Farm Bureau, which supported the higher EQUIP limits.

SALMONSEN: I think across the range— larger farms, smaller farms— with this what we’ve done, which is significantly increase the funding, we could address a whole range of projects we couldn’t even seek to address before.

CURWOOD: Anna, what do farmers make of this bill?

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Well, I won’t even try to speak for the hundreds of thousands of farmers across the country, but I think their response is pretty predictable. Farmers who grow corn and cotton and other staple crops, for them this bill’s good news. For farmers who grow fruits and vegetables and specialty crops, there’s not that much in it for them.

I also called some of the ranchers I met when I was out in South Dakota last summer. These are people who have been watching a lot of the grassland in their state get plowed up and planted into corn and soybeans for the government subsidies, and their feeling is, even with the couple hundred million dollars in this bill that are going to protect grasslands, compared with the 50 billion that are going into crops, they think they’re going to see more land be dug up. This is Jack Freeman. He’s a rancher in Faith, South Dakota.

FREEMAN: We did get a list off the Internet of who the big winners in this area were, you know, that were collecting in the $600,000 and the $100,000 range. And you can tell it when you drive by their machinery reserves; it’s pretty evident who’s making it work for them.

CURWOOD: Anna, before you go, there is one aspect of the bill that hasn’t got much attention I’d like you to tell us about. Those are the incentives that are in it to help farmers produce renewable energy and become more energy-efficient.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: That’s right. You’re talking about the energy title, and it’s the first time there’s been an energy title in a farm bill. I think that’s partly due to the politics of national security right now. I also think it’s due to the growing power of the ethanol lobby here in Washington. Ethanol got a big boost, you might remember, in the Senate energy bill a couple weeks ago. It gets another one in this farm bill. And there’s also some money to help farmers increase their use of wind and solar power. Overall, it’s not a lot of money. In total, there’s about $400 million for these energy programs.

But for the people who worked to get in here, it’s a huge step. They point out that only 20 years ago there was no conservation title in the farm bill. Now, as you’ve seen, it’s a regular part of the debate, and there’s $17 billion for it.

CURWOOD: Anna Solomon-Greenbaum covers Washington for Living on Earth. Thanks, Anna.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: You’re welcome.

[MUSIC]

Wing Dams

CURWOOD: The flood control projects of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers have changed some of the biggest rivers in America and prevented a lot of flood damage. But on April 30th the Army Corps announced that it was suspending work on as many as 150 water-related projects to assess their economic and environmental value. A recent study by the National Academy of Sciences found that some Corps projects are destructive to certain river ecosystems. And two researchers at Washington University in St. Louis say that some Corps projects may serve to make major floods worse.

They say that wing dams—structures that jut out into rivers—could cause waters to rise higher during floods than they otherwise would. Lester Graham, of the Great Lakes Radio Consortium, reports.

[SOUND OF BARGE AND RIVER]

GRAHAM: The Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers are two of the major arteries for barge transportation in America. Millions of tons of grain and raw materials are ported up and down the rivers each year. It’s the Army Corps of Engineers’ job to keep the rivers open to barge traffic. The Corps has been doing their job for the past 150 years. But since the 1930’s that effort has taken on immense proportions. Huge dams hold back the rivers, keeping the water high enough for the barges to travel up and downstream. Big earthen dikes called "levies" wall in the rivers, keeping them from flooding farms and towns, but also keeping the water from reaching the natural flood plains.

Robert Criss and Everett Shock study flood levels and the effects of the Corps of Engineers’ projects. Criss says those dams and levies alone might be enough to disrupt the flow of the river and cause flood stages to be higher.

CRISS: The other component is these structures called "wing dams," which are jetties of rock that project out perpendicularly into the channel. For high flow conditions these act something like scale in a pipe: they impede the flow, restricting the channel. That slows the velocity of the water down and that also makes the flood stages higher.

GRAHAM: The purpose of wing dams is to force the current to the middle of the river to scour out the navigation channel to keep it open for barges. Researcher Everett Shock.

SHOCK: So they do the job they’re intended to do. It seems that there’s a, perhaps, unintended consequence of all these constructions along the river that shows up when we have a big flood and makes it—on the basis of our study—makes these big floods worse.

GRAHAM: Criss and Shock say their study finds that since these flood control projects have been erected there have been more big floods, such as the one in 1993 that flooded the Mississippi and some of its tributaries for most of the summer. Robert Criss:

CRISS: The fact is, before World War II a flood stage of 38 feet is very rare and now it happens every five years.

GRAHAM: But not everyone agrees with the methodology used by the researchers. The Corps of Engineers dismisses the researcher’s study, saying they used flawed data. Corps officials point to a study at the University of Missouri-Rolla. That study compared the 19th century method of measuring the river’s flow by timing how fast floats moved in the current to the methods used today. Dave Busse is a scientist with the Army Corps of Engineers. He says the original stream flow measurements, the ones Criss and Shock used, were inaccurate:

BUSSE: The flows were over-estimated by 30 percent using these float measurements, rather than the measurements that we use today.

GRAHAM: Criss and Shock are skeptical of the new numbers the Corps prefers, saying it seems awfully convenient for the Corps because changing the numbers makes the historic floods look smaller and, therefore, makes the 1993 flood look unprecedented. Criss and Shock say based on the original record there was as much water in past floods as in the 1993 flood, but lower water levels. Criss and Shock say the difference between then and now is that the Corps’ dams, levies and wing dams constrict the river’s flow and make floods higher.

The Corps, however, has other criticism of the Criss and Shock study. Dave Busse says the researchers ignored the role of the Corps’ reservoirs in the rivers’ watersheds. Busse says reservoirs hold back water that would otherwise be part of a flood. And Busse says another flaw is the researchers’ conclusions about wing dams. The Corps says the wing dams force the water to deepen the channel and that increases the flow of the river.

BUSSE: It’s a reshaped river, but its carrying capacity is actually higher now. We can actually carry more water at the same stage. After we put wing dams in, the river got deeper. Therefore, this conclusion that they’ve made is wrong.

GRAHAM: The Corps says there’s more to managing the river than the researchers have considered. Criss and Shock, meanwhile, say their study is not the first to be dismissed by the Corps of Engineers. They say other studies have found similar results, but the Corps dismissed them, as well. Environmentalists have been arguing for decades that levies and dams keep flood waters from spreading out on the natural flood plains and, as a result, cause higher flood levels.

The Criss and Shock study adds to their arsenal of arguments to change the way the rivers are managed. But most environmentalists concede that we’ve become somewhat dependent on the Corps’ flood control projects. Chad Smith, with the environmental group American Rivers:

SMITH: In most ways, both of these camps are right. The Corps is right that putting some of this structure in has helped to reduce the kind of annual flood events that always happen on a big river like this. But what they unfortunately have done is to exacerbate what happens when you have bigger floods and the wing dams and the levies and the dams themselves all are a part of that.

GRAHAM: The Army Corps of Engineers says it’s reviewing its way of managing rivers in the light of the 1993 flood, but it also notes that while flood stages might be higher more often than they were in the nineteenth century, most of the time those flood waters remain behind the flood walls and levies, protecting communities from high water. And the Corps says in the end that’s the only fact that really matters. For Living on Earth, this is Lester Graham.

[MUSIC: Rachel’s, "Good Bye," SELENOGRAPHY (Quarter Stick – 1999)]

Department A/Tech Note

CURWOOD: Coming up, why sugary cereal and other sweets and grains may cause children to become near-sighted. First, this Environmental Technology Note from Cynthia Graber:

[THEME MUSIC]

GRABER: Scientists at the State University of New York in Brooklyn are developing a new tool to use in search and rescue operations and land mine detection: remote- controlled rats. While trying to build a prosthesis that can simulate the sense of touch, researchers discovered that when they applied electrical impulses to certain areas of a rat’s brain they could make the rat think its whiskers were being gently touched. Rats use their whiskers to help them navigate in and around tight places, especially in the dark. So the rats were suited up with a small backpack carrying a remote-controlled charging device and trained to respond to simulated whisker touches by turning either left or right.

Eventually, scientists were able to navigate the rodents around a room, even though the rats did the actual work themselves, figuring out how to climb over objects in their path and crawling into tight spots. One day, researchers hope this technology will allow the use of rats in search and rescue missions, especially in places too small even for dogs to access and places too dangerous for humans to go, like mine fields. As for whether this technology could one day be applied to people, the researches say that the complexity of the human brain would make mind control practically impossible. That’s this week’s Technology Note. I’m Cynthia Graber.

[THEME MUSIC OUT]

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Mighty Flashlight, "Thick Light," LIE (Quarter Stick – 1999)]

The Living on Earth Almanac

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: Ike Smith, "Mabel’s Dream," CRUMB (sndtrk) (Ryko – 1995)]

CURWOOD: As the weather warms up, you can head to the fridge for a tall glass of iced tea or a frosty mug of lemonade, all thanks to what happened in a sick room in Florida 160 years ago. That’s when Dr. John Gorrie got the idea for, what would become the precursor to, the modern refrigerator. 1842 was an especially hot, humid summer in the gulf-port town of Apalachicola, Florida and yellow fever had broken out in the town. So, Dr. Gorrie designed a mechanical ice-making machine to cool his patients down. He eventually got so caught up in the idea that he quit his medical practice, went to work in his lab and won the first U.S. patent for mechanical refrigeration in May 1851.

Before the refrigerator, people often used water, cool or frozen, to chill their food. The Greeks dug huge pits insulated with wood and straw and filled them with snow. Romans stored their food in clay pots, surrounded by water and fanned by slaves. And centuries ago, the English wrapped blocks of ice in flannel, packed them in salt, and buried them underground. But ordinary ice goes pretty fast in the middle of an August heatwave, so everyone who enjoys a quick and easy cold one during the hottest months might want to stop and lift a glass to Dr. John Gorrie. Hear, hear!

[SOUND OF BOTTLE OPENING AND LIQUID POURING]

CURWOOD: And for this week, that’s the Living on Earth Almanac.

Myopia

CURWOOD: Cereal, bread and sugar. These foods are staples of most diets. But a new theory suggests that eating them as a child can make you near-sighted. According to Loren Cordain, sugars and grains kick off a series of events in the body that can affect eye growth and lead to myopia. Dr. Cordain is an evolutionary biologist at Colorado State University. He studies paleo-diets—in other words, how ancient people used to eat. He’s also the author of a just-published paper that explains his theory about near-sightedness. Hello, sir.

CORDAIN: Hello.

CURWOOD: So, let’s get to your theory. I’m a child and I’m eating lots of white bread and candy. What could happen to my body that might lead to myopia?

CORDAIN: Well, we believe that when you eat lots of white bread and candy, these are what are called high-glycemic foods and they tend to elevate your blood sugar and your insulin levels. The elevation in insulin also causes an elevation of other hormones that regulate growth. And remember, myopia is a situation of uncontrolled growth.

CURWOOD: What’s the problem with the eye growing? You would expect an eye to grow as the child develops.

CORDAIN: You need to match the power of the cornea and the lens—which actually focus vision on the retina—you need to match the power of the cornea and lens to a growing eyeball. And so there has to be this dance; there has to be this coordination between the length of the eyeball and the focal power of the cornea and the lens. The hormonal signal that causes that is a substance called retinoic acid, and this chronically elevated level of insulin disrupts the retinoic acid signals.

CURWOOD: Let me be sure I understand what you’re saying here. The culprit here is not just sugar, but starchy food, in general, anything that raises insulin levels in the body?

CORDAIN: That’s right. Nutritionists have come up with a scheme of things which we call the glycemic index and we can rate how much a certain food elevates your blood sugar level. The higher the glycemic index, the more it raises blood insulin levels. Cereal grains. Virtually all cereal grains tend to have a high glycemic index.

CURWOOD: Now, it’s generally accepted that genetics and looking at things up close causes myopia. Your paper even mentions a study that shows that people began to get

myopia—that is, near-sightedness—after they started learning to read at an early age. How correct is this assessment of the problem of myopia?

CORDAIN: I think the thing is, when you look at reading, per se, is if reading should cause myopia, then the percentage of myopia in all populations that read ought to be somewhat similar. But the problem is, is that rural people— and there’s been a study done of rural people in a Pacific island— people don’t eat refined carbohydrates. They don’t have access to them. Yet, they have mandatory schooling. The children are required to read eight hours a day. These children, again, do not develop myopia— a less than two percent incidence rate— however, they’re reading for eight hours a day.

CURWOOD: Now, certainly lots of people who eat starchy diets have perfectly fine sight. Tell me, how significant a role do you think diet does play in myopia?

CORDAIN: Well, myopia results from the interaction of the environment and the genes. And there is no single gene that is responsible for myopia, there are multiple genes. And what we believe is that people who are genetically susceptible to insulin resistance are those that are most likely to develop myopia.

CURWOOD: Your paper isn’t new research, in the sense that you’ve gone out and conducted your own studies. Rather, it’s a review of other studies that have been published. And we spent some time talking with an ophthalmologist, who was recommended to us by the American Academy of Ophthalmology, and he found your study intriguing, but he said he wanted to see more original research. How do you respond to that?

CORDAIN: Well, I would agree with him entirely. I mean, what our group has done that is original research is we’ve put together all the pieces of the puzzle and that’s probably why you’re interviewing me now. How in the world can diet have anything to do with myopia? Because most people don’t have a clue of this entire metabolic cascade. That kind of information’s only been out there for a very short period of time and the idea that retinoic acid is the chemical messenger for myopia is only about a year or two old, as well.

CURWOOD: Loren Cordain is a biologist at Colorado State University. Thanks for taking this time with us.

CORDAIN: Well thank you. It’s been my pleasure.

CURWOOD: For more information on Loren Cordain’s research and for a discussion about his book on the dangers of high starch diets, visit our website at www.loe.org. That’s www.loe.org.

[THEME MUSIC]

Related link:

For more on starchy diets see our on-line version of this story">

Listener Letters

CURWOOD: Time for comments from you, our listeners. Phil Getty from Philadelphia, who hears us on WHYY, e-mailed in with a concern. "Your shows are informative," he writes," but the information can be overwhelming to listeners, who often are hearing bad news. For example, monarch butterfly habitat is being cut down. Attempts are being made to try to stop this, but it’s still being cut down. And you end with ’This year’s frost kill may be an indication of more permanent things to come.’ Why don’t you try putting an enabling statement at the end of each segment? After you capture the interest and heart of a listener, it is hard being left with a feeling that the world is going to hell."

Well, Mr. Getty, we understand how you feel, but we’re not here to promote causes or give out stamps of approval. But if you use the information we present to take action yourself, that’s fine, and that’s why we have a free press.

Indeed, KOPB listener Gerry Scheerens in Portland, Oregon, was inspired to call us with her solution to the monarch butterfly crisis.

SCHEERENS: I was thinking that maybe either the people that live there, or volunteers, could gather up the butterflies and either put them in contact paper and have, like, a sign saying "Buy me. Save a tree," and maybe we could sell them, and get people to understand what’s going on in Mexico. And that money, the proceeds from that, could go back to those people or to compensate them for the fact that they’re not being able to sell the trees.

CURWOOD: Thanks for the suggestion, Ms. Scheerens. And if you have one for us, call our Llstener line any time at 800 -218-9988. That’s 800-218-9988. Or write to us at Eight Story Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02138. Our e-mail address is: letters@loe.org. Once again: letters@loe.org. And visit our web page at www.loe.org. That’s www.loe.org.

[THEME MUSIC OUT]

Life With Abbey

CURWOOD: This year marks the 75th anniversary of the birth of the late Edward Abbey. Abbey was author of several classics of southwest literature and an inspiration for many people. A new profile of Edward Abbey has just been published. It’s written by a man who came to know Abbey from the hours the two spent around campfires, on hiking trails and driving all over the southwest in their beat-up pick-up trucks. Paul Ingles has our story.

[SOUND OF WIND]

LOEFFLER: This is my truck, the 1977 Chevy truck that Ed and I trailed around in a lot.

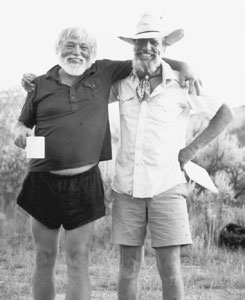

INGLES: 62-year-old Jack Loeffler resembles a summertime southwestern Santa Claus in shorts, t-shirt and neck bandanna. He stands outside his home on the outskirts of Santa Fe, resting his hand proudly on the road-weary chocolate brown pick-up that’s an active character in his new book, "Adventures with Ed: A Portrait of Abbey."

LOEFFLER: And actually, Ed’s last night above ground was spent right there in the bed of that truck.

INGLES: On March 14th, 1989, Ed Abbey died surrounded by family and friends in his Tucson cabin. Loeffler zipped Abbey’s body up in a sleeping bag, set it in a box of dry ice in the truck bed, and with the help of other Abbey friends, headed to a secret, remote site in the Sonoran Desert to bury him. As Loeffler quotes in his book, Abbey himself had spelled out the funeral instructions in a 1981 journal entry when his health began to fail.

LOEFFLER: "No undertakers wanted. No embalming, for God’s sake. No coffin. Just a plain pine box hammered together by a friend or an old sleeping bag or tarp will do. I want my body to help fertilize the growth of a cactus or a cliff rose or sagebrush."

Ed & Jack, circa 1985

(Photo: Katherine Loeffler)

INGLES: An appropriate last wish for a man whose writing often championed the cause of the environment. Abbey’s burial is the last of the "Adventures with Ed" that Loeffler chronicles in the book. Both Loeffler and Abbey moved west from different points in the rural east. They often took seasonal work as fire lookouts that put them close to the wilderness they both passionately wanted to protect. When the two finally met in the late ’60’s they shared much in common and became best friends.

Abbey went on to gain fame as a writer of essays and novels like "Desert Solitaire," "Black Sun," "The Brave Cowboy," and his most famous, "The Monkeywrench Gang," whose characters engaged in industrial sabotage, battling man-made developments that were overtaking the wild. Loeffler says Abbey didn’t just write about eco-shenanigans:

LOEFFLER: He was an activist. He did—we called it "night work."

INGLES: Details of Abbey’s, or Loeffler’s own, night work are purposely scant in the book to protect both his friend and himself. There are some tales of cutting down billboards and hints at disabling land-clearing bulldozers and coal-toting trains and trucks that Abbey saw as the tools of man’s environmental degradation. And there are several references to a recurring Abbey fantasy:

LOEFFLER: His great thought— and this is not something I’m suggesting here— but many’s the time that he considered taking out the Glen Canyon Dam. He saw the Glen Canyon before it filled up and became Lake Powell or Lake Foul, as Ed called it. That led to so many various other dire consequences for the southwest that it was, from his point, pretty hopeless and futile.

INGLES: Abbey called for divine intervention, at one point, on the dam. Loeffler reads from his book:

LOEFFLER: "In 1970 we stood on the bridge that spans the canyon immediately south of Glenn Canyon Dam. ’Are you a praying man, Loeffler?’ ’Not particularly.’ ’Are you willing to join me in prayer?’ ’What prayer?’ ’For an earthquake to shake that dam loose once and for all.’ ’I’ll pray for that,’ I said. Abbey and I got down on our knees and prayed as hard as we could. Ed prayed aloud, while I chanted. After several minutes, we gave it up."

INGLES: Can you still visualize that?

LOEFFLER: Oh yeah, can I ever. There were a lot of people there, including a ranger. They thought we were a couple of nuts. And who knows? Probably we were.

INGLES: Abbey bristled at detractors who labeled his night work "sabotage," "eco-terrorism."

LOEFFLER: The distinction is quite clear and simple.

INGLES: Loeffler reads from one of his interviews with Ed Abbey:

LOEFFLER: "Sabotage is an act of force or violence against material objects, machinery, in which life is not endangered, or should not be. Terrorism, on the other hand, is violence against living things: human beings and other living things."

ABBEY: I consider myself almost an absolute egalitarian.

INGLES: Edward Abbey, recorded by Loeffler in 1983.

ABBEY: I think that all human beings deserve equal regard or consideration. And I’m saying that that respect should be extended to each living thing on the planet: the mountain lions and the rattlesnakes and the coyotes, and plant life. I think a tree, a shrub, deserves respect, and sympathy as a living thing.

INGLES: Is it still emotional for you to hear his voice again?

LOEFFLER: Well, it’s interesting, Paul, because when I’m hiking, I still hear Ed talking to me when I’m walking down a familiar trail that we’ve both gone through or gone down. Ed was my best friend and fortunately, I’ve got enough of Ed scattered around here that I can refer to it. So to me, he’s dead, but he’s also very much alive.

INGLES: While Loeffler’s book is mostly a celebration of their friendship, he allows Ed Abbey’s contradictions to seep through. Although against over-population, Abbey married five times and had five children. And despite his defense of the environment, in one of the book’s episodes he’s tossing empty beer bottles out the truck window.

LOEFFLER: He, himself, was a human with the human foibles that many of us have and was not a perfect being. But I will say this: he was a man of great honor and he really did pursue the truth. And the truth, as he saw it, was that we’re in deep trouble on this planet and it’s up to all of us to turn that around, if it’s even possible.

[MUSIC: Craig Armstrong, "Finding Beauty," AS IF NOTHING (Virgin – 2002)]

INGLES: Jack Loeffler’s "Adventures with Ed: A Portrait of Abbey" is published by the University of New Mexico Press. For Living on Earth I’m Paul Ingles.

CURWOOD: You’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth.

[THEME MUSIC]

Related link:

"Adventures with Ed: A Portrait of Abbey" published by University of New Mexico Press">

News Follow-up

CURWOOD: Time now to follow up on some of the news stories we’ve been tracking lately. In January we reported about longwall mining. This underground mining technique can cause land on top of the mine to collapse, resulting in damage to landscapes, homes, and businesses. Recently, a federal district court banned longwall mining under national parks, homes, buildings, and roads. The home of Laurine Williams, on the National Historic Registry just outside Waynesburg, Pennsylvania, was damaged by mining last year.

WILLIAMS: When they went under our house, the first thing that happened was the front of the house went out about an inch-and-a-half. Our engineers had told us that if it had gone out two inches the house could have caved in on itself.

CURWOOD: According to the U.S. Interior Department, the new ruling protects Ms. Williams’ home and 30,000 others, along with more than 15,000 acres of parks and open lands, mostly in Appalachia.

To aid in the recovery of fish populations in the North Atlantic, a federal judge recently restricted the number of days New England fishermen can work and the areas they can work in. Priscilla Brooks, director of the Marine Resources Project at the Conservation Law Foundation says the harsh measures are needed.

BROOKS: Many of our fish stocks are only a quarter of what they could be. We have a long way to go to rebuild these fish stocks. The situation’s very serious out there and I think the judge’s order reflects the severity of the situation.

CURWOOD: But many fishermen say the new rules will force them out of business.

Recently, we reported on a dispute between the Bus Riders’ Union in Los Angeles and the L.A. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. The riders want more buses and more routes to serve poorer communities. At the time of the report, Chief MTA spokesman Mark Littman said in total, the public agency had spent about one million dollars fighting the Bus Riders’ Union suits all the way to the Supreme Court. But, in fact, a request by Living on Earth under California’s Open Records Law reveals that the agency spent nearly ten times that amount: $9.4 million dollars. We asked Mr. Littman about the discrepancy.

LITTMAN: I can only give you the information that I had. I was under the impression that it’s just a little over a million dollars.

CURWOOD: The L.A. MTA is buying new cleaner running natural gas buses now, but the Bus Riders’ Union says overcrowding on many routes remains a problem.

And finally, in Great Britain, scares over e-coli and salmonella poisoning have some restaurant owners worried about legal liability. So they’re making customers who prefer their meat rare sign a disclaimer absolving the restaurant of responsibility. And that’s this week’s follow-up on the news from Living on Earth.

Department B/Health Note

Just ahead: The impact of the eastern drought on fish. First, this Environmental Health Note from Diane Toomey:

[THEME MUSIC]

TOOMEY: Rift Valley fever is a mosquito-borne illness that infects both livestock and people living in eastern and southern Africa. In humans, rift valley fever can cause brain inflammation and lesions of the retina that can lead to partial vision loss, and there’s no effective treatment for the fever. Disease-laden mosquito populations can be controlled with insecticide, but outbreaks are unpredictable so it’s been difficult for public health officials to use those insecticides efficiently. Now, they’re getting some help from NASA satellites.

Researchers have discovered that outbreaks of Rift Valley fever follow sudden floods triggered by the El Nino factor in the Pacific and a similar phenomenon in the Indian Ocean. Both produce a warming of sea surface temperatures that can lead to alterations in rainfall patterns. Researchers say they can now predict Rift Valley fever outbreaks up to five months in advance by using these weather satellite data. To pinpoint the most vulnerable areas, forecasters also use the satellites to produce a greenness index. The greener the region, the greater the rainfall and, therefore, the more mosquitoes.

Researchers say the technology could also help predict another disease that’s rainfall-dependent: hanta virus outbreaks in the American southwest. That’s this week’s Health Note. I’m Diane Toomey.

[THEME MUSIC OUT]

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Euphone, "Destroyed the 80’s," LOCATION IS EVERYTHING (Jade Tree – 2002)]

Fish Out of Water

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. And coming up: some people find them icky, and some people find them yummy. The eel is next. But first, many parts of the United States are experiencing abnormally dry or drought conditions. In the East, New Hampshire has declared a drought emergency and in Maryland, stream levels are the lowest ever recorded. Many states, including Connecticut, are asking citizens to conserve water voluntarily. But as Nancy Cohen reports from Connecticut, it isn’t only people who are affected by the shortage of water. It’s absolutely vital for fish.

[SOUND OF RUNNING WATER]

COHEN: Imagine for a moment that you’re a fresh water fish. You’re covered with scales, breathing through gills, and, in a typical spring, your home would be brimming with chilly, deep water. Not this year.

HYATT: The water levels that are currently confined to a relatively small channel should be nearly twice as wide and, at least, a couple feet higher.

COHEN: Bill Hyatt of Connecticut’s Department of Environmental Protection is sitting on dry rocks that hug the edge of Salmon Brook in Glastonbury, a spot that, he says, would normally be covered with two feet of rushing, ice-cold water.

(Photo: courtesy of Marla Blair)

HYATT: What we’re looking at now are water levels that are far more typical for the very end of spring, the beginning of summer.

COHEN: Hyatt says if water levels continue to drop on brooks like this, fish may become more crowded and exposed. There will be fewer riffles in the water. Those are the places where the water tumbles over rocks, creating white water, bubbles, and oxygen—a good place for fish to hide from birds of prey lurking above, such as heron or osprey.

HYATT: Overhead cover, turbulent flow, are all types of habitat that provide protection from predators. And those will diminish greatly as the summer goes on and, in the case of a severe drought, will be almost non-existent.

COHEN: Less water also means higher water temperatures, and water temperature is critical for fish. Unlike mammals, who have a relatively constant body temperature, a fish’s body temperature is regulated by the cold or warmth of its surroundings.

HYATT: When the water temperature rises to a higher level than it normally is their body temperature goes up and their metabolism goes up, as well, and that requires them to start feeding and to remain active for longer periods of the day.

COHEN: Right now, the warmer temperatures are making fish hungrier and making them easier for fishermen to catch.

[SOUND OF CROW CALLING AND WATER]

COHEN: One of the best places in Connecticut to catch trout is the Farmington River. What makes this river so special is the constant flow of water from two reservoirs upstream. In a normal year the water is cold, making the river ideal for trout. David Goulet, owner of the Classic and Custom Fly Shop right on the Farmington is worried that come summer the drought could make the water flowing into this river too warm for trout.

GOULET: The reservoir won’t have sufficient depth to make the cold water. Instead of being 43 degrees it could be 50 degrees. So then, we have the natural warming. When we get into the warm weather we get these stretches of 80, 90 degrees. Evenings, we don’t get a cooling off period. So that heat starts to stay in the river, and we’ve never had that here. So we don’t know how our fish are going to react.

COHEN: Goulet pays close attention to fish behavior and especially to what they eat. Not only does he sell hand-tied flies to fly fishermen; he tracks the hatching of real aquatic flies, which make up much of a trout’s diet. This year, the flies are hatching early.

GOULET: We have one particular bug that’s seven weeks ahead of schedule. The problem comes when everything accelerates and we’re into June, when this bug should have came out, and is now in, out, gone. What happens in June?

COHEN: With all the flies hatching ahead of schedule, Goulet is afraid there won’t be enough food for the trout after June. And even if there are flies, the water could get so warm, trout stop eating. This could be an even bigger problem on rivers and streams that aren’t fed by reservoirs, were fish depend only on natural flows from rain, surface run-off, and ground water. If the water gets too warm, fish will live off their body fat and even their eggs, which could hurt reproduction.

GOULET: When you start getting up into the 70 degree range they become lethargic. It’s overwhelming their body, it’s taxing their body. They probably don’t want to feed. They don’t feed, they’re getting skinny. They get skinny, they’re losing body weight, they’re getting themselves in trouble. When you get up to 80, it’s lethal. They die.

COHEN: But right now, fishing is good. Conditions are typical of those later in the season.

[SOUND OF BIRDS AND WATER]

COHEN: On a recent evening, a handful of people dressed in waders tested their skill against the fish. Standing waist deep in the Farmington River, they flexed their fishing rods back and forth overhead. Their lines dance in the air and land gently on the water. Jon Vaughn hooks a fish and slowly reels it in before letting it go. He’s one of the many fishermen who enjoys the sport of fishing, but doesn’t take home his catch.

BLAIR: What did you get?

[SOUND OF FISH SPLASHING]

VAUGHN: It’s a rainbow trout. Pretty good looking fish, nice and healthy. Still got some energy in it.

COHEN: Just upstream, fishing guide Marla Blair describes fishing on this river as heaven on earth, but she’s worried the season could be cut short this year.

BLAIR: My joy is to see people catch fish. I may not be able to make that happen. If this water warms up to the point where the fish will get stressed if my clients fish them, I can’t have them on the river.

COHEN: For now, though, the fish are jumping. But many share Blair’s concerns. Some biologists predict that if we don’t get a heavy dose of spring rain this could be a tough summer for fresh water species. For Living on Earth, I’m Nancy Cohen on the Farmington River.

[SOUND OF WATER FLOWING AND FISH SPLASHING]

Related link:

U.S. Drought Monitor">

The Elusive Eel

CURWOOD: Some people travel the world for adventure, for fine food, or just the thrill of it. Author Richard Schweid found all three when he hit the road in pursuit of something most people would rather avoid: the eel. From the Sargasso Sea to the rivers of Spain and beyond, Mr. Schweid follows the slithery fish and writes about his experiences in his new book, "Consider the Eel." He says his discoveries about this humblest of creatures have inspired a sense of wonder and mystery and also made for some really great eating along the way. Richard Schweid, welcome to Living on Earth.

SCHWEID: Hi Steve.

CURWOOD: Why did you yourself decide to consider the eel? What was the experience that, pardon me, hooked you?

SCHWEID: It trapped me, actually. I was out with a guy in sort of an inland, marshy lake down below Valencia, and the guy trapped some eels as part of the way he made his living. And he trapped one the morning I was out with him in his boat. And he took us back to a cafe in town and went in the kitchen and cleaned the eel—which was nice of him to do—and cooked it for us. And when he served it to us he said, "You know, it’s an amazing thing. An eel is just an incredible animal." And we said, "Well, it tastes pretty good. What else is so amazing about it?"

And he told us the story of how all eels come from the Sargasso Sea, that very deep sea in the Atlantic Ocean between Bermuda and the Azores, and he told us the story of how they all came thousands of miles and then came into the rivers of Europe. And I thought to myself, "This is one of the most gullible people I’ve ever met in my life. This is the most ridiculous story I’ve ever heard," and we went on about our business. And later I found that he had it exactly right.

CURWOOD: What’s the biggest mystery you found about eels?

SCHWEID: Well, the biggest mystery is, without a doubt, how does an eel maintain such an odd lifestyle? All those eels are born in the Sargasso Sea and there the currents carry them either to the rivers of North America or the rivers of Europe. And then some 15, 20, 25 years later they turn around at some signal that nobody knows what it is, and go back to the sea, and they stop eating once they hit saltwater. They go down the river and they jettison their entire digestive apparatus, and their eyes open up so that they can see down in the depths of the sea. And they go through all these changes and then they swim down to the Sargasso, where, theoretically, they mate and they die.

CURWOOD: We don’t know how they replicate themselves?

SCHWEID: The scientific theory that eels reproduce at depths in the Sargasso Sea is— the only evidence we have for that is that the larvae that have been found on the surface of the Sargasso are so small, so infinitesimally small—five millimeters—that they had to have been born close by. And, of course, we have observed eels coming back down the river and going into the sea. But what happens to them once they get into the sea, no one’s ever seen and no one’s ever been able to track them. A considerable amount of money has been spent with sophisticated sonar-equipped ships trying to track adult eels as they head out into the open Atlantic and, to date, no one’s ever been able to even get close. They lose them about as soon as they get them.

CURWOOD: By the way, the eels we’re talking about are fresh water eels.

SCHWEID: These are fresh water eels.

CURWOOD: These aren’t the big guys, the morays and the electric fellows that you can find deep in the ocean?

SCHWEID: No, these are the eels that you might—many a fisherman living fairly close to the east coast might think that they’d gotten a good fish when they get a pull on their line and they reel it in. And much to their horror, it’s an eel. This is the kind of eel we’re talking about. It might live in a lake or a pond or a river near you.

CURWOOD: Now, I’m wondering. You’ve been studying the life cycle of eels for quite awhile. What observations or comparisons might you make between eels and us humans?

SCHWEID: I’d say eels have got all the good. We had all the bad. It’s much better to be an eel, Steve.

CURWOOD: Really?

SCHWEID: I think so because, look at it this way. We have a pretty monotonous life. We keep the same form. Although we grow we keep, more or less, the same form for our whole lives, whereas an eel begins as a larva, a tiny little leaf out in the middle of the great Atlantic Ocean. So it finds fresh water and its body transforms into a thin, transparent ribbon which then grows over the course of years into, what we know as, an eel. So anyhow, that’s my general take on it. I think humans have got kind of a raw deal, really. I think the eel got all the best of the evolutionary process.

CURWOOD: One of the things that you key into your book is that the eel population is declining. What are the threats to eels and why are they particularly vulnerable?

SCHWEID: Changes in oceanographic temperature may be having some effect on the number of eels that hatch out and the number of viable eels that manage to make their way across the ocean to fresh water. And then again, there are some places in Europe, for instance, where there is a certain market for the elvers— for the very tiny eels that are just coming from the saltwater into the fresh water—and they can be sold to Japan directly or they can be sold to China because the Chinese are investing heavily in raising eels to marketable size to sell to the Japanese. So that there are years in which when the Japanese eel recruitment is down the Chinese buy their eels from the Europeans— their little babies. And there are years in which tiny eels have been worth more per kilo, say, than heroin.

CURWOOD: Now, all this to consider the eel. If you ask most Americans to eat eels, well, they probably wouldn’t— right? But what about the eel market in other parts of the world? Who really likes these creatures?

SCHWEID: Almost everybody else likes them. Everywhere that they appear, they’re eaten with great avidity. It’s only in the United States where eel is not consumed so much and that was one of the reasons that I really wanted to consider the eel myself. And many, many people in the United States ate eel right up until the mid-nineteenth century. And after the Civil War it began to decline until the consumption of eel has essentially evaporated and disappeared.

(Photo: courtesy of UNC Press)

CURWOOD: You write that in Spain, chefs there prepare baby eels called elvers, or I guess in Spain the word is "angulas," in a special way. Can you read a little from this, please?

SCHWEID: Sure. Glad to. "No one is certain just who is the first to stop throwing the angulas to the pigs and begin tossing them in a frying pan instead. Angulas a la Vizcaina are elvers flash-fried in cold-pressed, extra virgin olive oil, and served in an earthenware bowl with minced garlic and a pepper with a mild sting called a "guindilla." They’re served while sizzling hot and are eaten with a wooden fork, because a metal utensil might burn the diner’s lips. On the menus of San Sebastian’s Restaurants, the price of one can reach $70 or $80 a serving during the season, each serving a quarter of a pound. They’re quite tasty, like a slightly grainy pasta with a tiny crunch in the backbone and a faint aftertaste of fish and garlic, along with the guindilla’s light bite."

CURWOOD: Seventy, eighty bucks a serving!

SCHWEID: Well, I have to say that I tasted them all in the line of duty, you know. I tasted them and the chef insisted that I have it and that he wasn’t going to charge me for it.

CURWOOD: What’s your favorite way to prepare eel?

SCHWEID: Well, I tend to go along with the Dutch and German. Smoked ell, to me, is just delicious. I like eel sushi. And I like all kinds of eel, really. I’ve never eaten eel that I didn’t like at all. My least favorite was probably jellied ell, which is something they still eat in great quantity in London, which is simply chunks of eel in gelatin, served usually in a styrofoam paper cup like you’d get a cup of coffee-to-go in, and then you put either regular vinegar or hot vinegar on top of that. The English love it, particularly in London’s East End. It used to be one of the favorite foods. But I didn’t find it particularly tasty.

CURWOOD: Richard, tell me, what surprised you most doing the research about eels for this book?

SCHWEID: Well, I think the biggest surprise to me was the fact that so many people have spent so much time and so much money trying to understand, what seems to be, such a humble and basic animal. And with all of that effort and energy and expenditure, people still know next to nothing about the eel.

CURWOOD: Richard Schweid is a journalist and author of "Consider the Eel." He spoke to us today from Barcelona, where he’s senior editor of Barcelona Metropolitan, a magazine. Richard, thanks so much for taking this time with me today.

SCHWEID: Thanks very much for having me. It’s been a pleasure.

[Ocio, "Quasar," IN OUR LIFETIME (Fenway Records – 2002)]

Related link:

"Consider the Eel" by Richard Schweid">

CURWOOD: And for this week, that’s Living on Earth. Next week: the controversy over human cloning. Advocates say it will give us better control over human health and reproduction, but critics say cloning is unethical and could change human values.

WOMAN: Many of the technologies that we’re talking about do turn having a child into something akin to buying a car, picking the extras and so forth. And I’m worried about the effect on relationships, the effect on society, if we do look at children that way.

CURWOOD: The human cloning debate is the topic when our series, "Generation Next: Remaking the Human Race" continues next week on Living on Earth.

[SOUND OF DOLPHINS]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week with the Blue Men of the Minch. We’re not sure exactly what that means, but that’s the title of this underwater recording featuring roaring seals and the distinctive navigating clicks and whistles of blue-nosed dolphins. The chorus was captured by Chris Watson on Scotland’s Moray Firth.

[Chris Watson, "Blue Men of Minch," STEPPING INTO THE DARK" (EarthEar – 2002)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us anytime at www.loe.org. Our staff includes Jennifer Chu, Maggie Villiger, Jessica Penny and Al Avery, along with Peter Shaw, Leah Brown, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson and Milisa Muniz. Special thanks to Ernie Silver. We had help this week from Rachel Girshick and Jessie Fenn. Allison Dean composed our themes. Environmental sound art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our technical director is Dennis Foley. Ingrid Lobet heads our western bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor. And Chris Ballman is the senior producer of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood, executive producer. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER #1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include the Educational Foundation of America, for coverage of energy and climate change; the Ford Foundation for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues; the Oak Foundation, supporting coverage of marine issues; and the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation, supporting efforts to better understand environmental change.

ANNOUNCER #2: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth