February 14, 2003

Air Date: February 14, 2003

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Climate Change Lawsuit

View the page for this story

Several cities, along with conservation groups, are suing the Export-Import Bank of the United States and the Overseas Private Investment Corporation. The plaintiffs allege that these federal agencies are violating the National Environmental Policy Act by not filing information on how the projects they fund contribute to climate change. Host Steve Curwood talks with Pat Parenteau of the Vermont Law School about the case. (06:00)

Rising Tides

View the page for this story

Jesse Williford is a plaintiff in the climate change lawsuit. He’s concerned that rising sea levels and increased intensity of storms will add substantial costs to building his retirement home on Emerald Isle in North Carolina. In a sound portrait, we travel to Emerald Isle and listen to Mr. Williford’s concerns. (05:00)

Health Note/Chemo-Prevention

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on a new drug derived from Vitamin A that may help former smokers ward off lung cancer. (01:15)

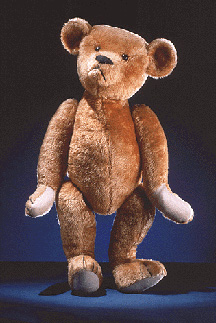

Almanac/Teddy’s Bear

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about the first Teddy Bear. It was one hundred years ago that hunting enthusiast President Teddy Roosevelt lent his name to the stuffed animal. (01:30)

High Dose/Low Dose

View the page for this story

Living On Earth’s Steve Curwood speaks with toxicology professor Edward Calabrese about a paradigm shift that may be brewing in the toxicological field. The concept of hormesis may explain how our bodies react to very small amounts of toxins. (05:00)

Natural Drains

/ Gordon BlackView the page for this story

All over the country dirty storm water is piped directly into creeks and lakes. In Seattle, a novel alternative is instead using storm water for landscaping and as a result, beautifying the neighborhood. Gordon Black from KUOW reports. (05:30)

Cold Comfort

/ Gussie FauntelroyView the page for this story

Layers, layers and more layers. That, and a philosophy of conservation, is how commentator Gussie Fauntelroy stays comfortable working indoors without heat in the winter. (03:00)

Emerging Science Note/Snow White

/ Jennifer ChuView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Jennifer Chu reports on new weather technology able to detect high-level clouds previously undetected by the average weather balloon. (01:20)

Toxic Sprays on Bouquets

/ Clay ScottView the page for this story

America’s love affair with perfect flowers may come at a cost: the toxic chemicals used to keep the flowers flawless may be harmful to workers’ health and consumers, as well. Clay Scott reports. (08:45)

The Biology of Love

View the page for this story

Just in time for St. Valentine's Day, Steve Curwood interviews German ethnobotanist Christian Rätsch about his new book called "Plants of Love: The History of Aphrodisiacs and a Guide to their Identification and Use." Dr. Rätsch's volume details the historical and often successful search for substances that can enhance sexual pleasure and provoke both love and fertility. (05:45)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodGUESTS: Pat Parenteau, Jesse Williford, Edward Calabrese, Dr. Christian RatschREPORTERS: Gordon Black, Clay ScottCOMMENTATOR: Gussie FauntleroyNOTES: Diane Toomey, Jennifer Chu

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. If you went looking for organic flowers for Valentine’s Day, chances are your local florist didn’t have any.

OLIVEIRA: I haven’t had a customer come in asking for organic, non-pesticides, to tell you the truth.

CURWOOD: That’s because most of us want the flawless flower.

MILLS: No water stains, no fertilizer marks, no dead leaves, yellow leaves, anything. It has to be perfect.

CURWOOD: On the other hand, we’ll gladly take certain flowers and plants, even if they’re not so pretty. They’re called aphrodisiacs, and they’re prized as nature’s little libido boosters.

RATSCH: It’s like a sexual arousal from the bottom of your body, and that goes like electricity up your spinal cord, until it reaches your brain.

CURWOOD: The love plants and more, this week on Living On Earth, coming up right after this.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living On Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and HeritageAfrica.com.

[THEME MUSIC]

Climate Change Lawsuit

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Three U.S. cities are going to court to force the Bush administration’s hand on its climate change policy, and they’re using an unusual legal strategy. Boulder, Colorado, and Arcata and Oakland, California, along with the environmental groups Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace, have filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court in northern California.

Their suit alleges that the Overseas Private Investment Corporation and the Export-Import Bank of the United States, don’t follow the rules when they fund coal and other fossil fuel projects abroad that emit greenhouse gases. Under the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA, the government must conduct environmental assessments of its activities if they might harm the environment. The cities say there’s ample evidence that burning fossil fuel is changing the climate and adversely effecting their local environments. And they claim the government has failed to assess the impact of climate change from its lending programs.

The U.S. Justice Department isn’t talking about the case while it’s pending. But I did speak with Pat Parenteau, professor at Vermont Law School, who’s been following the case. He says the plaintiffs hope to bring greater scrutiny to federal energy policy.

PARENTEAU: It’s kind of a double whammy. I think the political point that these cases are making is it’s bad enough that we’re not getting our own house in order, but when you take taxpayer money and invest in polluting facilities in the rest of the world, you really have to ask the question: what are we doing, and why are we doing it?

CURWOOD: Let’s look at the law involved here in this case. What do the plaintiffs need to prove to win?

PARENTEAU: They have to demonstrate primarily that the projects that these two institutions are funding are, in fact, increasing CO2 emissions. And then they’re going to have to make a connection between the increase in CO2 from these projects and effects that can at least be identified as potentially significant. They don’t have to prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that this is what’s happening, but for purposes of NEPA, they have to show there is a credible threat as a result of the actions that these two agencies are taking.

CURWOOD: And what do you think the defense will say here?

PARENTEAU: Their initial move will be to say “we’re not even going to address your arguments that we’re not complying with NEPA because you, individuals, and you, cities, don’t have the required standing to bring this case.” So, they will be challenging the plaintiffs to demonstrate how they, individually, are affected by global warming. If they fail to get the case dismissed, then they’re going to argue “well, we’re already doing this kind of environmental assessment. It’s true that we don’t involve the public in that. But we do internally look at the impacts of what we’re doing. And what we’ve found is there’s very little impact. So there’s really no need here to go to the trouble of doing an environmental impact statement, since our own analysis shows there’s really not a big problem.”

CURWOOD: I’m noticing something rather interesting in this case--tension over where, in fact, to hold it. The plaintiffs have filed in California. The government wants the case moved to Washington, D.C. What’s going on here?

PARENTEAU: The plaintiffs want to be in California because that’s the best place to be if you’re an environmental plaintiff. The courts in that part of the country have been very open to allowing environmental organizations to sue under statutes like NEPA. And so, they want to remain there and they’re arguing that’s where their headquarters are located for two of the conservation organizations. That’s where the City of Arcata and the City of Oakland are located, obviously. So, they’re saying, we belong here. The government, on the other hand, would like the case to be heard in Washington, D.C., where the court that oversees that part of the country is much more conservative and requires a much higher showing for environmental groups to demonstrate this requirement of standing or injury.

CURWOOD: How important is this case against the international financing agencies in the realm of U.S. policy and climate change?

PARENTEAU: Once the principle is established here that NEPA does require agencies to consider the effects of their actions on global warming, then I think you can see a lot of other cases being filed challenging other federal actions and agencies that are also involved in activities that may affect global warming. So, you might see a cascading effect where this case triggers another case, or at least triggers other agencies to wake up and start asking themselves “wait a minute, are we doing things that are making global warming worse, and are there some things that we could do that would make it better?”

CURWOOD: It seems that the season is upon us to sue the federal government over climate change. There are other cases. Particularly, I’m thinking of the recent announcement by Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Maine that they have filed formal notice to take the Environmental Protection Agency to court, demanding that the EPA regulate carbon dioxide as a pollutant under the Clean Air Act. Can you explain to us the difference between that case and the Overseas Private Investment Corporation/Export-Import case?

PARENTEAU: Yes. That’s a very interesting case, very different from the NEPA case. That’s claiming that the Environmental Protection Agency has a mandatory duty to list carbon dioxide as what’s called a “criteria pollutant” under the Clean Air Act. And unlike NEPA, which simply requires that the impacts be disclosed to the public in an Environmental Impact Statement, the Clean Air Act actually has teeth. It says if there’s a pollutant being emitted and it’s not meeting the standard the EPA has set for it, then it has to be reduced. So that case has some very interesting potential to actually require significant reductions in CO2 emissions in the United States.

CURWOOD: Pat Parenteau is a professor of Environmental Law at Vermont Law School. Thanks so much for taking this time.

PARENTEAU: Thanks for having me on, Steve.

Related link:

Climate change lawsuit website

Rising Tides

CURWOOD: Pam and Jesse Williford are among a group of citizen plaintiffs in the NEPA climate change lawsuit. The Willifords live in Raleigh, North Carolina, and hope to build a small retirement home on Emerald Island on North Carolina’s outer banks. Jesse Williford says he and his wife are concerned that rising sea levels, increased storm severity, and erosion resulting from climate change will add a substantial cost to building their dream home.

Jesse and Pam Williford.

WILLIFORD: I, first of all, came down to Emerald Isle about 1970, so a good 30 years ago. And my wife and I have come down just about every year since then, and bringing our family down. So, we’ve been coming down pretty regular for about 30 years. About 25 years ago, we purchased a lot down here because we were very interested in retiring down here. It’s such a nice, peaceful place, and has such nice, wide beaches. And the lot that we purchased is about 1,000 feet from the ocean. So you can actually see the sand dunes that border the beach from the edge of the lot.

[OCEAN SOUNDS, WALKING ON DECK]

WILLIFORD: As you see from where we’re sitting on top of this deck now, it looks like, to me, we’ve lost 20 or 30 feet of this particular sand dune. I think the biggest amount of sand is lost during the hurricanes. When the hurricanes…the frequency of the hurricanes and the strength of the hurricanes has really taken away that sand. Since these islands are all just sand, just pure, white sand, you expect to have some erosion and some movement. But the thing that’s concerned me about the global warming is, as ice melts in some places, then the sea level increases, you know, very small kinds of amounts. But that means there’s going to be more erosion whenever that happens.

[SAND COMING OUT OF A PIPE]

WILLIFORD: They’re adding sand to the beaches here, just trying to replenish the sand that was lost. Because if the dunes keep getting eroded, then the houses on the main front of the beach are going to be eventually washed away, or the foundations will be washed away, and then they will be condemned. And eventually they’d be destroyed. So they’re trying to put the sand back to kind of save those houses and preserve our tax base. Because these houses along the beach here at Emerald Isle pay a tremendous amount of taxes. They go to the support of the county itself. So that’s why they’re having to replenish the beach here.

A sand replenishment program is set to shore up

the eroding beaches of Emerald Isle.

[TRUCKS BACKING UP, FOOTSTEPS ON LEAVES]

WILLIFORD: The lot, over the last 25 years, we’ve let it just kind of grow. And so, we have not cleared anything out. So, it’s a little thicker than it used to be. But some of our trees have died out, which is kind of scary…some of the large trees. They haven’t been dead that long. My guess is probably three or four years, along that line. I suppose that goes back to a hurricane that we had in 1996. Hurricane Fran, and I think, also, Hurricane Bertha came through. And what was unusual about both Bertha and Fran was that somehow or another there was a tremendous amount of salt spray that kind of went across the island, and many cedar trees were killed. Of the 30 years we’ve been coming down here, that was the only time I’ve seen that much salt spray do that much damage to the vegetation and to the trees.

[WALKING, OCEAN SOUNDS]

WILLIFORD: The plans that we originally had were to build a small kind of cottage, hopefully not too expensive. But now it seems like we’ve had more hurricanes over the past few years, so it makes us more concerned about our building. We need to make sure we build it strong enough. I think the codes over the years have changed, and may change some more.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

WILLIFORD: I’m very surprised that I’m here talking about this today because I never pictured myself as getting involved. I’m usually pretty low key and kind of take things as they come and go. But as I see some things that kind of directly effect me -- which would be the island -- seeing some major changes in that one, and seeing the trees getting damaged, and then concern about being able to build here on the lot that I’ve got, and to think that my government is doing some things, or not doing some things, that are causing this pollution and this climate change to happen. And that’s going to harm the environment for all of us, all the people in the world.

CURWOOD: Jesse Williford lives with his wife, Pam, in Raleigh, North Carolina. The Willifords are plaintiffs in the NEPA climate change lawsuit.

Health Note/Chemo-Prevention

CURWOOD: Just ahead, keeping trouble from going down the drain. Seattle tests the powers of bio-remediation. First, this Environmental Health Note from Diane Toomey.

[MUSIC: HealthNote Theme]

TOOMEY: The use of a drug derived from vitamin A may help protect former smokers against lung cancer by restoring production of a crucial protein. Although smokers reduce their risk of developing lung cancer when they quit, whatever cell damage they’ve done up to that point doesn’t disappear right away. Half of all lung cancers occur in former smokers. So researchers hope to find a way to repair this cell damage before it turns cancerous.

The drug used in this study belongs to a class of compounds known as retinoids. Retinoids play an important role in regulating the epithelial cells that line the lung. To do that, these retinoids must first latch on to their matching protein receptors. But smoking reduces the number of these receptors, making lungs vulnerable to cancer. It’s known that retinoids can restore the production of this protein receptor.

So, in this study, a few dozen former smokers were given an oral dose of retinoids for three months. Another group of former smokers was given a placebo. Researchers performed lung biopsies on the patients before and after the treatment. They found that in patients who receive the drug, the percentage of biopsies that showed the presence of the important protein receptor rose seven points. But in the placebo group, this percentage dropped six points. Although this study doesn’t prove the drug turned pre-cancerous cells into healthy ones, researchers say it demonstrates that so-called chemo-prevention of lung cancer may be possible.

And that’s this week’s Health Note. I’m Diane Toomey.

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Faithless “Intro” Back to Mine - Ultra Records (2001)]

Almanac/Teddy’s Bear

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living On Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: Elvis Presley “Teddy Bear” ELV1S 30 #1 Hits - RCA (2002)]

CURWOOD: When you were small, you took it everywhere, and maybe you still do. It’s fuzzy and soft, and turns 100 this week. It’s the Teddy Bear. The cuddly stuffed animal that got its name from the avid bear hunter, President Theodore Roosevelt. As the story goes, the presidential hunting trip was arranged in Mississippi back in 1902. But when no bears appeared, Teddy Roosevelt’s companions tracked down the only one they could find – a raggedy old bruin that they tied to a tree so the president could claim his prize. But the suffering animal had wounds from hunting dogs and Roosevelt couldn’t bear to shoot. Instead, he ordered it euthanized.

The story made the news through a political cartoon drawn with some artistic license. It portrayed TR sparing an adorable bear cub. Citizens warmed to this tender image of their president, and a Brooklyn candy store owner saw dollar signs. He contacted the White House and asked for permission to sell a synthetic toy cub named Teddy’s Bear. The president was unimpressed with the idea, but gave permission anyway, and Teddy’s Bear made its debut in a Brooklyn store window in 1903.

(Courtesy of Smithsonian’s

National Museum of American History)

From the early wire jointed teddies, to a 1985 talking Teddy Ruxpin, the species Ursus Teddy keeps evolving. But if you want to visit the original Teddy’s Bear, you won’t have to wrestle it from a toddler. The centenarian cuddly is safe and sound in Washington, D.C. at the Smithsonian Museum of American History.

And for this week, that’s the Living on Earth Almanac.

[MUSIC FADES]

High Dose/Low Dose

CURWOOD: For decades, toxicologists assumed that if high exposure to a chemical is bad for you, then exposure to a small amount will be bad for you too, but maybe not as bad. But today, some scientists think the situation is more complicated than that. They believe small doses might actually have the opposite effect of large doses of the same toxin. Dr. Edward Calabrese is a professor of Environmental Health Sciences at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. He has just published a commentary in the journal Nature, about the need for a toxicological paradigm shift. He joins me now.

Dr. Calabrese, you’ve examined many studies that support the idea of hormesis. Just what is hormesis?

CALABRESE: Hormesis is a dose response phenomenon in which, essentially, if it’s talking about pollutants here, we could anticipate having a beneficial effect at a low dose, followed by the traditional adverse effect at a higher dose.

CURWOOD: So, hormesis implies that while a lot of some things is bad for you, a little might be good. The flip question--what evidence is there that small amounts might be toxic, and quite large amounts might be good for you?

CALABRESE: Usually, you don’t see that. I’ve seen situations where high doses could be bad, and very low doses could also be harmful. For example, with the prostate, where you could have a high dose cause a shrinkage of the prostate, whereas a low dose might cause an increase. And you’d be finding that any change from normal could be harmful.

CURWOOD: What very toxic chemicals could actually be perceived as good for us in small doses?

CALABRESE: I’d have to say that, probably, just about every one that could come to your lips. From the toxic heavy metals, including arsenic and cadmium, lead, mercury, these things that--

CURWOOD: Dioxin?

CALABRESE: Dioxin would be considered one of the most toxic chemicals known to mankind. The classic study that the U.S. EPA uses to derive the risk assessment numbers for us actually demonstrated that low levels of dioxin in the diet of the experimental rats actually significantly reduced tumors from, essentially, all the monitored sites in male and female rat bodies, only increasing the tumor incidence at the higher doses.

CURWOOD: If hormesis suggests that small, perhaps very small, doses of toxic chemicals might well be good for you, why doesn’t industry wildly promote this idea?

CALABRESE: Industry doesn’t know quite what to do with this because in the last 15 years or so, even though there’s been some sort of rancorous interactions between the U.S. EPA and industry, I think in many ways they’ve come to their accommodations, if you know what I mean. They understand the rules of the game. They know how to conduct their studies. They know how to fit into the EPA risk assessment scheme.

And what hormesis does, is it really changes the rules for both the government and industry. And I think, in many ways, it makes people on both sides of the equation uncomfortable because it creates uncertainty.

CURWOOD: What steps will have to be taken before regulators can get their arms around this concept?

CALABRESE: Well, you know, I think that the most important thing is for them to actually give it sufficient priority to look at the data. I think once people actually do look at the publications, actually do embrace the quest for truth in the low dose zone, I think that changes will naturally follow. But what hormesis is really arguing is that the field of toxicology should redefine itself to look at the entire dose response spectrum, including the low doses that we commonly encounter in our own personal lives. And once we do begin to look at the lower doses, we find that, gee, the predictive models that the EPA and the FDA have been using are really, for the most part -- I don’t want to call them antiquated -- but they’re inadequate to address the reality of where we live, which is in, for the most part, a low dose world.

CURWOOD: Dr. Edward Calabrese is a professor of Toxicology at UMass Amherst. Thanks for taking the time to speak with us today.

CALABRESE: Thank you very much.

[ANIMAL SOUNDS]

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Just a few months ago I was in the back of a Land Rover driving across the African Savannah under a crystal clear sky. As the sun was setting, we came across a solitary leopard trying to pull an antelope up into a tree. As we watched, we realized the leopard had a cub with her. Now, our trackers have told us that these animals on the game preserves regard folks in Land Rovers as part of some relatively huge, benign animal, and usually they’ll let you get close.

But this mom, with her baby and antelope dinner, was in no mood for strangers. She walked right up to our truck and glared at us. A chill ran down my spine, as I realized that we were just one swat away from her. And that would happen long before our tracker could grab the rifle on the dashboard in the Land Rover. I’ll never forget the look in the leopard’s eyes. She said, “This is my meat, my kid, I’m the boss.”

Now, Living on Earth wants to give you chance at your own African Safari. Thanks to Heritage Africa, we’re giving away a 15-day trip for two on the ultimate African safari, with visits to several of Africa’s most spectacular game preserves such as Kruger, where I saw this leopard, and the Serengeti. For more details about how to win this 15-day African safari, just go to our website, loe.org. That’s www.loe.org, for the trip of a lifetime.

[MUSIC]

Natural Drains

CURWOOD: There’s a movement across the nation for neighborhoods to adopt and restore local streams, and the fish and other aquatic life they support. In Seattle alone, since 1999, $26 million dollars and countless volunteer hours have been spent on bringing back city creeks. But new studies show that storm water may be negating these efforts. Runoff laced with antifreeze, lawn chemicals and pet feces is killing fish, including some fragile salmon species.

From Seattle, Gordon Black of member station KUOW reports on an alternative. Instead of piping dirty storm water into creeks, officials are trying a botanical solution, one suited to the city’s wet climate.

BLACK: Broadview is a neighborhood of ranch style homes in north Seattle that was laid out in the 1950s. The streets are wide here, but lack sidewalks. Ditches about a foot deep line the roadways to carry away rain water. Denise Andrews is a policy manager with Seattle Public Utilities and has driven these streets countless times.

ANDREWS: This is a typical North End neighborhood. You have smaller, single family homes. Some have very nice landscaping. But, in general, as you pull up in front of someone’s home, the street just sort of peters out into their property. There’s no piped infrastructure. A storm water sheet flows across the street and just follows the path of least resistance down the hill.

BLACK: These sheets of water pick up speed. Then they dump right into a creek that the city has been trying to restore as salmon habitat.

ANDREWS: In a good storm, you’re flushing all of the fish eggs, all of the bugs that the fish live on. It’s basically like flushing a toilet.

BLACK: After witnessing urban runoff destroy their carefully restored salmon stream, city officials decided to tackle the source. They worked up an alternative drainage plan, but they needed a neighborhood willing to endure nine months of construction to build it. They got lucky by attracting the interest of Joe O’Leary, a pragmatic civil engineer and long time Broadview resident.

O’LEARY: I think the key point, of course, was that it was unique. What the city was proposing was very different from what we had, not only in this neighborhood, Broadview, per se, but throughout the city, as well.

BLACK: O’Leary liked the idea of improving storm drainage so much, he went door-to-door to enlist support. Although the city was picking up the $800,000 tab for improving drainage on the block, Seattle utility officials admitted nothing like this had ever been tried before in the country. Still, O’Leary and several of his neighbors were buzzed by how they could help restore salmon runs in the creek, and maybe end up with a prettier street in of the bargain.

O’LEARY: We have 17 houses on the block. We had 16 people that we finally came up with that were convinced of the project. There was one neighbor, of course, that was adamantly opposed to it.

BLACK: O’Leary thinks that even that neighbor is now pleased with the results. It’s easy to see why. An unremarkable street has been transformed into a park like landscape that invites a stroll.

O’LEARY: What’s been so very positive are the people from outside the neighborhood that have been visiting and just think it’s a wonderful project, a very positive thing that the city has done.

[DOG BARKING]

BLACK: Instead of a pencil-straight road, the street has been narrowed and curves gently. Front yards blend into a border of shrubs and trees planted in long hollows called bio-swales. These swales are the heart of the new drainage system on the block. The plants are a mixture of decorative species like butterfly bushes and dogwood, and water tolerant grasses and irises. They provide double duty, filtering out harmful pollutants as well as absorbing moisture.

This is important because asphalt changes the chemistry of storm water, says Derrick Booth, a University of Washington research geologist who studies urban watersheds.

BOOTH: Water that runs off a parking lot has a very different set of constituents than water that has fallen through a tree canopy, soaked into the ground, and moves slowly as ground water. So we have both a quantity problem and a quality problem.

BLACK: In fact, the new drainage system tries to mimic the forest floor. Now, say utility officials, 98 percent of storm water is soaking into the ground, just as it would in a natural setting.

ANDREWS: That’s a phenomenal number. It basically means that if you could apply this technique in areas where it’s appropriate, where it’s draining to creeks, where there is no formal infrastructure currently in place, you can severely reduce the amount of storm water that’s wrecking the creek.

BLACK: Geologist Booth is impressed by the success of the pilot street, but is cautious about how well these natural drains will hold off in the long term.

BOOTH: They have not yet been stressed, if you will, or hammered by a really major storm to see how they perform in the once every five years, once a decade events that we do sometimes get around here, and which certainly do provide some our most severe water quantity problems.

BLACK: Following the success of the pilot street, work crews are putting the finishing touches on a more ambitious project--a six-block steep hill. And the experiment is quickly growing. Over the next two years, Seattle Public Utilities is planning to create bio-swales with plantings in a 15-block area of the city.

For Living on Earth, I’m Gordon Black, in Seattle.

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation. Major contributors include the Ford Foundation for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues, and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation for coverage of western issues. Support also comes from NPR member stations, and the Noyce Foundation, dedicated to improving math and science instruction from kindergarten through Grade 12. And Bob Williams and Meg Caldwell, honoring NPR’s coverage of environmental and natural resource issues, and in support of the NPR President’s Council.

Cold Comfort

CURWOOD: Folks who live in the Northeast and Midwest have endured one of the longest winters that anyone can remember, with above average snowfall and below average temperatures. And the season is far from over yet. Meanwhile, in the Sangre de Christo Mountain Range of New Mexico, commentator Gussie Fauntleroy is taking winter in stride. She has decided you don’t need to keep your house warm to stay comfortable.

FAUNTLEROY: It’s amazing how much warmer this house feels when the thermometer in the living room reads 50 degrees instead of 45. My office in the northwest corner has made it up to 47, after lingering in the low 40s. On the coldest mornings, icy crystalline lace often spreads across the inside of the window panes. Now, in relative warmth, the moisture trickles down the glass.

The American ideal is to slip from toasty house, to pre-warmed car, to perpetually heated buildings. We rarely stop to think about the swift depletion of the earth’s ancient store of compressed energy, as we keep our toes warm on a winter floor. Still, I have to admit, my life in a walk-in fridge began not with principle, but practicality. With the decision not to use the ridiculously expensive baseboard electric heaters in this poorly insulated, tree-surrounded house, or to spend the time and money it would take to keep the wood stove burning non-stop.

As it is, I light the stove each evening and enjoy its comfort and warmth until bedtime.

Eyebrows go up when I tell someone the room where I sit at my desk all day is 45 degrees. But the secret to keeping warm is simple--multiple layers, starting with silk long-johns, and ending with a thermal vest, a polypropylene cap, and down-filled booties. Every day, November till April.

For certain, I don’t advocate this lifestyle for everyone, not even myself in the long run. My dream house will be warm in winter, well insulated, completely off the grid, and heated by the sun. But for now, at least, I can truthfully say I like living this way. There’s an element of realness to it. And there are side benefits. No need to remember to put the beer in the fridge. On the other hand, no dinner guests until summer. I enjoy being aware of the subtle changes of season. I’m grateful for the empathy I’m able to feel with the millions of people who, for whatever reason, are not in warm shelter on winter nights. I pray in thankfulness for what I have. I pray with hope for the people who need so much.

[MUSIC: Dusted “Childhood” Back To Mine Ultra Records (2001)]

CURWOOD: Writer Gussie Fauntleroy lives at 7,000 feet in the mountain foothills near Santa Fe, New Mexico. A longer version of her essay first appeared in Orion magazine.

Related link:

Link to Orion magazine for a longer version of this commentary

Emerging Science Note/Snow White

CURWOOD: Just ahead, a few herbal recipes for loving. First, this Note on Emerging Science from Jennifer Chu.

[MUSIC: Science Note Theme]

CHU: Using a new technology they’ve nicknamed Snow White, researchers at the National Center for Atmospheric Research have detected clouds high in the atmosphere that have, until now, been hidden from the average weather balloon. Their findings suggest that decades of climate data have underestimated the amount of cloud cover in the atmosphere.

Snow White is a state of the art humidity sensor that uses a chilled mirror and a light beam to measure water vapor. Researchers deployed a weather balloon outfitted with Snow White and two balloons with the standard humidity sensors used by most weather services. They sent the balloons six to nine miles up into the atmosphere. Data from Snow White found a thin layer of humidity, measuring 90 to 100 percent, suggesting the presence of cirrus clouds. The two average sensors only detected 30 percent relative humidity in the same region.

The existence of water vapor is rare in such a high and cold atmosphere, but researchers believe that even small amounts of water vapor and cirrus clouds can effect long term climate monitoring, and what they call the earth’s radiation budget. Layers of clouds act to trap heat in the earth’s atmosphere. The National Weather Service plans to revamp its weather balloons over the next four years. At this stage, however, their plans do not include Snow White.

That’s this week Note on Emerging Science. I’m Jennifer Chu.

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Jeff Friedman “I’m Ramblin’, Too” Slo and Lo - Accurate Records (2003)]

Toxic Sprays on Bouquets

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Americans spend $20 billion dollars a year on flowers, and the biggest day, as you might imagine, is Valentine's Day. But fewer and fewer of these blossoms are coming from local producers and the neighborhood florist. Small, family-run greenhouses have been pretty much swept aside by global corporations, and more and more flowers are being sold by supermarket, drug and convenience chains. And as Clay Scott reports from San Francisco, our passion for beautiful flowers may be taking a toll on human health, both in the U.S. and abroad.

SCOTT: It's three o'clock in the morning and most of San Francisco is asleep, but the city's sprawling flower market is open for business. In a dozen warehouses at the corner of Sixth and Brannon Streets, scores of florists are already at work. They walk briskly from stall to stall, styrofoam coffee cups in hand, choosing their day's supply of flowers from among the incredible variety on display.

MALE: …15 Barcelona, 20 number two French, 16 hyacinth…

SCOTT: Under the bright fluorescent lights, the surreal colors make your head spin, and the air is thick with heavy, sweet, tropical smells. The San Francisco Flower Market, one of the oldest and largest in the U.S., once sold only locally grown flowers. Not anymore.

FLOWER SELLER 1: They come from all over the world: Ecuador, Colombia. Probably, that's about 20 percent of our sales, are roses from Ecuador.

FLOWER SELLER 2: You see more imports. More imports.

FLOWER SELLER 3: South America, Mexico. They come from all over.

SCOTT: More than two-thirds of the flowers sold in the United States now come from South America. In 1991, Congress passed the Andean Trade Preferences act, giving South American flower growers exemption from U.S. import tariffs. The idea was to encourage the development of crops other than coca plants, used to make cocaine.

A decade later, while the drug trade shows no sign of drying up, the South American flower industry has proven to be nearly as lucrative. And it's easy to see why the flowers are so popular. Looking through the Ecuadorian and Colombian roses, with their silky petals and brilliant colors, it's almost impossible to find one with a blemish. But that perfection comes at a cost.

OLGA: [speaking Spanish]

SCOTT: Olga is a flower worker from Colombia. Answering questions I e-mailed to an interpreter in Bogotá, she talks about the years she spent picking 350 roses a day, until she got so sick she could no longer work. Her muscles and bones ached, she says, and she felt dizzy and nauseous. She blames those symptoms on daily exposures to the many pesticides used in Colombian greenhouses.

OLGA: [speaking Spanish]

SCOTT: There's very little protective clothing for workers, Olga says. The bosses don't allow enough time for the pesticides to go away before they send you back in, sometimes just 10 or 15 minutes after they fumigate. They don't even care if women are pregnant.

Colombian workers are often sent back to work in greenhouses shortly after pesticide spraying.

OLGA: [speaking Spanish]

SCOTT: Over 100 types of fungicides, herbicides, insecticides, and preservative chemicals are approved for us in Colombia's flower industry, including more than a dozen, such as aldicarb and metanil, severely restricted in the U.S. as probable carcinogens. Many flower workers in Colombia and Ecuador, the majority of them women, echo Olga's complaint that they are forced to re-enter the greenhouses too soon after spraying. That's an issue of growing concern to those who study the effects of pesticides.

Dr. Gina Solomon is assistant professor of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco. She's also senior scientist for the environmental advocacy group Natural Resources Defense Council.

SOLOMON: In an open field where there is a breeze and there is some dilution, it may be possible to re-enter relatively soon. In a greenhouse where the air is not circulating or exchanging, entering too soon could be like walking into a gas chamber.

SCOTT: Many of the acute health effects of pesticide poisoning, such as vomiting, diarrhea, tremors, mimic common illnesses. That's one reason, says Gina Solomon, that pesticide poisoning is so often misdiagnosed. And, there are potential long-term effects that are even more dangerous and more difficult to recognize. Ray Chavira is a scientist in the San Francisco office of the Environmental Protection Agency.

CHAVIRA: Workers throughout the whole stage of the process in greenhouses always have to be concerned because there are some pesticides that are carcinogens. There are some pesticides that cause neuro-toxic effects. There are some pesticides that cause reproductive effects. So there is a whole plethora of different types of pesticides, whether they are fungicides, insecticides, herbicides that are used in greenhouses.

SCOTT: Studies have linked long-term pesticide exposure to Parkinson's disease, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, leukemia, brain tumors, prostate and breast cancers. There is ample evidence, says Margaret Reeves of the Pesticide Action Network, that the majority of the pesticides used in the flower industry are hazardous. It's urgent, she says, that conditions for greenhouse workers be improved.

REEVES: We need to take a precautionary approach right now. Eliminate this idea of the burden of proof being on the victim to demonstrate that their sickness has been caused by a particular pesticide, and put the burden of proof on the industry and the producers of the pesticides to demonstrate that the pesticides are, in fact, safe.

SCOTT: Pesticide Action Network is supporting the efforts of South American flower workers to organize, but that's not easy in a country like Colombia where trade unionists have been the victims of harassment and assassinations.

Meanwhile, there are growing concerns that the flower workers might not be the only ones at risk. South American roses are often heavily sprayed just hours before being cut, and the residues can linger for days, or longer. Which means that the flowers you give your sweetheart almost certainly contain residues of pesticides. Since flowers are not a food crop, those pesticides are not regulated by the U.S. federal government. Still, says the University of California's Gina Solomon, you may not need to work in a greenhouse to be affected by them.

SOLOMON: Consumers don't think to protect their skin when they're handling flowers, and yet their skin is a vulnerable portal of entry by which pesticides can get right off of the flower stems, flower leaves, and flower petals right into their bloodstream and into their bodies.

SCOTT: Even here in San Francisco, where many consumers demand chemical-free food and fair trade coffee, there seems to be little awareness of the issues surrounding pesticides and flowers.

OLIVEIRA: Yeah, that'll be actually cute, if it's short, but just cut it. Okay.

[CASH REGISTER BEEPING]

SCOTT: In San Francisco's inner sunset district, florist Heidi Oliveira is doing a brisk business. Her shop is stocked with orchids, lilies, and roses from around the world. I ask her if there's much demand for pesticide-free flowers.

OLIVEIRA: I haven't had a customer come in asking for organic, non-pesticide. I've never even heard of a completely organic farm, to tell you the truth.

SCOTT: In shop after shop I get the same answer from florists. Suzie Mills’ family has been in the flower business for years.

SCOTT (to Mills): If you had, you know, let's say locally grown, organic flowers that were maybe not perfect, do you think you could sell them?

MILLS: No, I don't.

SCOTT: So, there's just a huge pressure to have something perfect?

MILLS: Yeah, perfect, exactly. No water stains, no fertilizer marks, no, you know, dead leaves, yellow leaves, anything. It has to be perfect.

SCOTT: Responding to that pressure, South American flower farms continue to spray at frequent intervals, despite growing evidence that the practice puts workers at risk. Dole Food Company is the largest flower producer worldwide, and one of the largest in Colombia. Officials at Dole declined comment for this story.

In Switzerland and Germany, meanwhile, consumers can now buy South American roses with a fair flower label, meaning that the flowers were produced in accordance with the four year old International Code of Conduct for the Production of Cut Flowers. Growers who sign the code agree to follow basic environmental, labor, and human rights standards. A small number of Colombian flower farms have responded to that demand and signed the code of conduct.

But the United States remains by far the largest market for Colombian and Ecuadorian flowers. And most flower growers are unlikely to change their practices as long as U.S. consumers continue to demand a perfect flower at any cost.

For Living on Earth, I'm Clay Scott in San Francisco.

Related links:

- International Code of Conduct for the Production of Cut Flowers (PDF document)

- Pesticide Action Network

The Biology of Love

CURWOOD: We often give flowers and plants as tokens of love, and there's some biology behind our motives. Vanilla beans, for example, are considered an aphrodisiac. Likewise, the aroma of clary flowers from a type of sage plant is said to kindle erotic desire.

I learned all this a few years ago when I interviewed German ethnobotanist Christian Rätsch. He's the author of a book called “Plants of Love: The History of Aphrodisiacs and a Guide to their Identification and Use.” In the spirit of Valentine's Day, we're re-airing our interview in which Dr. Rätsch told me that while alcohol is the most universal aphrodisiac, thorn apples and chili peppers are said to do the trick too. Some aphrodisiacs are regulated substances and others, like hemp and cocaine, are illegal in many places. But Dr. Rätsch says one of the most potent erotic herbs is legal. It hails from West Africa and it's called yohimbè.

RATSCH: Well, yohimbè is the name of the tree, or of maybe several different species of trees in Western Africa. And the bark of this tree has been used for millenia to enhance potency for ritual purposes, for sexual rituals, and also for enhancing pleasure. And in the 19th century, it was discovered by German travelers. And they found the use in Africa and tried it on themselves, and they found it astonishing what effect they got from it. And so it became quite famous.

CURWOOD: Have you tried this yohimbè?

RATSCH: Of course, many times.

CURWOOD: Well, how was it?

RATSCH: Well, I found it very, very interesting. First, I experimented with the bark, which was, like, a little stimulation only. But then I tried the pure compound in different dosages on myself. It was like the--what in Eastern philosophy is called the Kundalini power. It's like a sexual arousal from the bottom of your body, and that goes like electricity up your spinal cord until it reaches your brain. And it's all vibrating stimulation, which is, like, amazing, and very pleasurable.

CURWOOD: Now, some of the plants you talk about in your book here, though, you’ll get into trouble. I mean, I see hemp, that's marijuana, that's good for jail. Cocaine, or the coca shrub, that's good for jail. Have you tried these yourself?

RATSCH: Well I don't know how National Public Radio will react to what I say, but as a scientist I believe that I have to try the stuff I study to really understand what they do. And if cocaine or hemp is a way to jail in the United States, that doesn't mean it's as bad as that in other places of this planet.

CURWOOD: Now, in your book you say that aphrodisiacs help prevent divorce. Is this true? And how exactly?

RATSCH: I got this as a quote from old Sanskrit literature of India. They say aphrodisiacs are not for young men; they are horny enough. Aphrodisiacs are for married couples because they need this as a kind of medicine to stay together. Because when people live as a couple for a long time, they might get a little tired or disgusted by the other, or not get any more excitement. And to keep this excitement, to keep the relationship fresh, they advise to take aphrodisiacs, and I think that's wonderful. And I do exactly the same thing with my wife. I mean, we are together for almost 18 years, and we tried lots and lots of aphrodisiacs together. And it was like a good enrichment to our life, and we are still happy lovers.

CURWOOD: [laughs] Okay. Now, if you could tell me, using ingredients that would be relatively easy for someone in this country to find, and legal in this country, can you give us a simple recipe for Valentine's Day?

RATSCH: Well, of course, we haven't been talking about a shrub called damiana. That is a totally legal herb you can get everywhere and it is called the “plant of love.” And it comes from Mexico, and it also grows in California. And you can make teas out of it, you can use it as an incense, or as a tobacco substitute, you can put it into liquor and make an extraction. And it gives a very subtle sensation, but it makes your body warm and pushes blood in your upper parts, and just gives you a more pleasant feeling, and that is no problem at all.

CURWOOD: Dr. Christian Rätsch is author of “The Plants of Love: The History of Aphrodisiacs and a Guide to their Identification and Use.” It must have been hard to get this book published.

RATSCH: Well, in Germany it was very easy, but in the United States it took about seven years that a publisher was willing to do a translation. Because the writing is quite open and it's--well, of course, I go for sex and plants.

CURWOOD: Thank you so much.

RATSCH: You're welcome.

CURWOOD: Bye bye.

RATSCH: Bye bye.

[MUSIC: Kiss “Calling Dr. Love” The Very Best of Kiss - Universal (2002)]

CURWOOD: And for this week, that's Living on Earth. Next week, a photographer puts down his camera, closes his eyes, picks up a microphone, and for the first time hears what he's been missing all these years.

HAND: In the field, as soon as I put the camera away and pull on a set of headphones, the world seems to shift. With a camera around my neck, I passed this meadow by a dozen times. I was oblivious to the swirling world of willets, swallows, snipes, and wrens.

CURWOOD: One journalist goes from sight to sound, next time on Living on Earth.

And remember that between now and then you can hear us anytime, and get the stories behind the news by going to loe.org. And while you're there you can also get a chance to win a safari for two to Africa. That's loe.org.

[WHALE SOUNDS: Earth Ear “Cry of Youth” The Dreams of Gaia Earth Ear Records (1999)]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week with a cry of youth. That's the title Kathy Turco gave this recording she made of a young humpback whale practicing his mating song in a marine sanctuary in the deep Pacific off Mexico.

[WHALE SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by The World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at www.loe.org. Our staff includes Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Cynthia Graber, and Maggie Villiger, along with Al Avery, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson, and Liz Lempert.

Special thanks to Ernie Silver. We had help this week from Katherine Lemcke, Jenny Cutraro, Nathan Marcy, and George Olsen of Public Radio East. Allison Dean composed our themes. Environmental Sound Art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our technical director is Chris Engles. Ingrid Lobet heads our western bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor. And Chris Ballman is the senior producer of Living on Earth.

I’m Steve Curwood, executive producer. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation. Major contributors include: The National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science, and The Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living on Earth's expanded internet service. Support also comes from NPR member stations and the Annenberg Foundation, and the Helmut W. Shuman Foundation, supporting the arts, education, health, and the environment.

ANNOUNCER: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth