June 12, 2015

Air Date: June 12, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Losing Frozen Earth Could Cook the Planet

View the page for this story

As temperatures increase globally, thawing permafrost starts to release large amounts of carbon dioxide and methane, which, in turn, raise global temperatures. Woods Hole Research Center’s Susan Natali tells host Steve Curwood about new measurements of the possible carbon loss, and how this positive feedback loop has very negative consequences and research shows we are getting close to runaway global warming. (06:45)

G7 Calls for an End to Fossil Fuels

View the page for this story

At a recent meeting in Germany seven leading democratic nations announced their goal to make the world fossil fuel free by the end of the century. Jennifer Morgan of the World Resources Institute discusses the news with host Steve Curwood and gives an update on the progress of international climate talks in the run-up to the negotiations this fall in Paris. (07:45)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In Beyond the Headlines this week, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about how a donut chain joins the fight over tar sands, varying interpretations of EPA’s statements on fracking and ground water, and the start of a massive firestorm that consumed Yellowstone 27 years ago. (04:10)

Chimps Like To Cook

View the page for this story

As well as sharing common ancestors, chimpanzees and humans have other surprising similarities. Host Steve Curwood speaks with Dr. Felix Warneken, Associate Professor of Psychology at Harvard University, about his team’s experiment at a Chimpanzee Rehabilitation Center in the Congo. Their findings suggests that chimps possess several of the skills that allowed early humans to cook food and evolve into homo sapiens. (10:25)

BirdNote®: Bird Song, Music, and Neuroscience

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Listening to the birds sing brings deep joy to many people, and so does music. But how the birdsong and music relate is a mystery that scientists are now struggling to unravel, as Michael Stein explains. (02:00)

New Music Brings John Muir's Story to Life

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

John Muir, one of the fathers of American conservation, helped establish many of the west’s national parks. Now an urban chamber music group called Chance is celebrating Muir’s history and conservation legacy with a narrative concert that incorporates vocals, strings, and readings from his works. Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer reports on “John Muir, University of the Wilderness”. (10:35)

The Place Where You Live: East Claridon, Ohio

/ Anne KelseyView the page for this story

Living on Earth is giving a voice to Orion magazine’s longtime feature where people write about their favorite places. In this week’s edition, Anne Kelsey takes us to East Claridon, Ohio, where her family has owned land for 100 years and the morning quiet on the pond seems sacred. (05:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Sue Natali, Jennifer Morgan, Felix Warneken, Anne Kelsey

REPORTERS: Helen Palmer, Peter Dykstra, Michael Stein

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Meeting in Germany, G7 leaders have pledged deep cuts in global warming gases, and UN negotiators have been crafting a new climate treaty, but they don’t factor in the thawing of the frozen earth that could cook the planet.

NATALI: Our current estimate is that there's about fifteen hundred billion tons of carbon in permafrost. If all of the carbon in permafrost was released into the atmosphere, at that point, this is not going to be a habitable planet for humans.

CURWOOD: We might need a new ice age to save us. Also, a new view of the great conservationist John Muir as a young Rube Goldberg forever inventing things.

WILLETT: They were inventions like clocks, and one alarm clock that was rigged up to a device that would raise the top half of his bed — so it kind of threw him out of bed, if you can imagine that [laughs].

CURWOOD: We’ll have that and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable, place to live.

Losing Frozen Earth Could Cook the Planet

As much as 70% of the surface permafrost in the northern hemisphere may be gone by the end of this century. (Photo: Awing88, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The thawing of the permafrost in the far north is part of “growing irreversible feedbacks from the poles to Mount Everest,” and we are “reaching thresholds where only a new ice age reverses impacts.” That’s the word at the recent round of UN climate negotiations in Bonn from scientists whose alarming projections show we are at risk of slipping into runaway global warming.

In a moment we’ll have more on the negotiations and the G7 pledges to stem greenhouse gas emissions. But first, we turn to scientist Sue Natali of the Woods Hole Research Center in Massachusetts, who told negotiators about the new data and projections of what science calls “permafrost carbon feedback.” She joins us on the line now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

NATALI: Thank you very much. It’s great to be here.

CURWOOD: So, first of all, what's permafrost?

NATALI: Permafrost is perennially frozen ground. It's ground that remains frozen for two or more consecutive years. In some areas, permafrost has been frozen for up to 40,000 years. Permafrost can comprise any material that's in the ground that's below zero degrees Celsius, so it can contain rocks, frozen soil, organic material, so that you can find whole plant parts or trees or tree roots; you can find frozen bones.

Melting permafrost can create thaw ponds like those above, near Hudson Bay. (Photo: Steve Jurvetson, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: What happens when permafrost starts to thaw out?

NATALI: So one of the things that happens when permafrost thaws is you can get ground collapse, or ground subsidence, and the reason for that is because permafrost contains ice. When the ice melts, the ground can collapse. The other thing that can happen is if permafrost completely thaws, so that you get a breach, total breach in the permafrost layer, you can get drainage of groundwater and this can lead to drying. One of the things that we're seeing in boreal and Arctic regions is an increase in fire. If the soil dries, this may further amplify this increased fire frequency.

CURWOOD: So how does permafrost affect the global climate?

NATALI: Permafrost thaw affects global climate because there's currently a vast storage of carbon that's frozen in permafrost. So our current estimate is that there's about 1,500 billion tons of carbon in permafrost. That carbon is frozen. It's in the form of organic matter, so when the permafrost thaws, microbes decompose or eat that organic matter, and just as we respire carbon dioxide, so do microbes. So microbes release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and they also release methane. And methane is important because it's a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

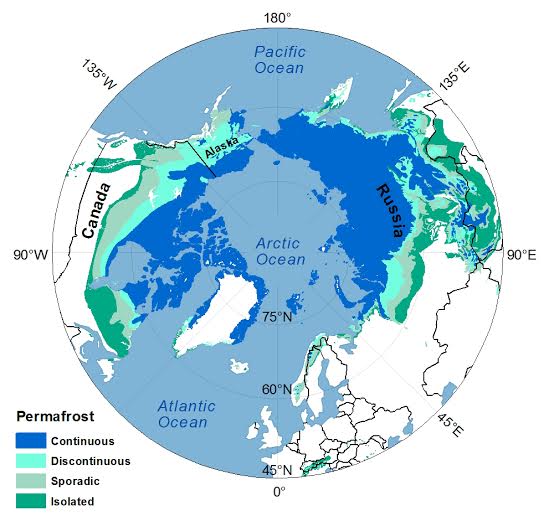

Permafrost currently comprises about 25% of the Northern Hemisphere land surface. (Map created by Greg Fiske. Data from Brown, et al. 2001 NSIDC)

CURWOOD: So why is it thawing?

NATALI: Permafrost is thawing as a result of climate change. In the Arctic, the air temperatures are warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet, and this is projected to continue into the coming decades and centuries.

CURWOOD: How much permafrost is there?

NATALI: Permafrost regions comprise about 25% of the northern hemisphere land area.

CURWOOD: And how much of it do we expect to lose?

NATALI: Our current projections are that we can expect to see a 30 to 70% decline in near surface permafrost, and that range in large part is driven by our different emission scenarios. So under low emissions we can expect about a 30% decline in permafrost. But under our current emissions scenario it’s up to 70%.

Above, Natali carries a carbon dioxide flux chamber, used for measuring CO2 uptake by plants and release from plants and soils. (Photo: Christy Lynch Designs)

CURWOOD: What are we talking about in terms of carbon winding up in the atmosphere here? How might this affect the whole planet?

NATALI: Right. So if 70% of our permafrost thaws, our current estimate is that by the end of this century, we can expect to lose 130 to 160 billion tons of carbon from permafrost as a result of thaw. So to put that in perspective, in 2013 the United States emitted 1.4 billion tons of carbon from fossil fuel combustion and cement production. Greenhouse gas released from permafrost regions is on par with emissions from the United States.

CURWOOD: So how does the carbon in the permafrost compare to other sources, other places, where carbon is on the planet?

NATALI: The amount of carbon in permafrost is almost twice as much carbon as is currently contained in the atmosphere. There's three times more carbon stored in permafrost than is contained in the world's forest biomass on a global scale, and the amount of carbon in permafrost is on par with our current estimates of fossil fuel reserves. And the thing that I think is important about these numbers is that when we think about the world's forests and deforestation, in theory, we can control deforestation and land use change. We can control our fossil fuel emissions, but once permafrost starts to thaw, we cannot control how much carbon dioxide and methane is released by microbes into the atmosphere from thawing permafrost.

CURWOOD: How much is the release of carbon from permafrost factored into the current climate negotiations?

NATALI: Permafrost carbon emissions were not included in the last IPCC report, but scientists are working to incorporate permafrost carbon release into Earth system models, so that our next climate projections can include this additional carbon loss as a result of permafrost thaw.

CURWOOD: So you're not a climate modeler, Dr. Natali, but if you factor in permafrost thaw to climate projections, how does that change things do you think?

Dr. Susan Natali researches the effects of climate change on terrestrial ecosystems at Woods Hole Research Center in Falmouth, MA. (Photo: Christy Lynch Designs)

NATALI: Well, international negotiators had set two degrees Celsius as an upper limit, an acceptable level of climate change. To remain below the two degrees Celsius target, our total emissions are limited to 790 gigatons, or billion tons, of carbon. We've already released about 500, so that leaves us a little under 300 billion tons. We can expect 150 of that to be taken up as a result of permafrost thaw. So this makes it very challenging for us to stay below this two degrees Celsius. Even under our lowest emissions scenario, we're pretty close to 2.2 degrees Celsius. We're about a quarter of a degree away from that. Factoring in permafrost emissions is extremely urgent, and what this means is this puts greater urgency on reducing our fossil fuel emissions.

CURWOOD: So, alright, I'm sitting down, you can tell me, if we get all the carbon in the permafrost into the atmosphere, how warm is our planet, do we know?

NATALI: Not all of the carbon that's in permafrost will be released. Our current expectations is about 10 to 15% of that carbon will be released into the atmosphere. That said, if all of the carbon of permafrost was released, at that point, this is not going to be a habitable planet for humans.

CURWOOD: Sue Natali is a Permafrost Expert with the Woods Hole Research Center and co-author of a paper recently published in “Nature.” Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Sue.

NATALI: Thank you so much for having me.

Related links:

- Woods Hole Research Center press release on permafrost

- About Susan Natali

- About permafrost from NOAA

- Methane and Frozen Ground

- “Climate change and the permafrost carbon feedback” (coauthored by Susan Natali)

- Scientists raise permafrost alarm at UN climate talks

- UNEP Report: “Policy Implications of Warming Permafrost”

-

CURWOOD: There’s more information about threats related to the thawing permafrost on our website LOE.org, including a link to this paper in the journal “Nature.”

G7 Calls for an End to Fossil Fuels

The G7 declared that the fossil fuel era needs to end this century. (Photo: Robert S. Donovan, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Sue Natali spoke in Bonn to UN negotiators working to streamline a new binding climate treaty for delegates to discuss and, with luck, adopt in Paris next fall. The session coincided with the G7 nations meeting further south in Germany, where leaders, including those from historically reluctant Japan and Canada, agreed to call for a full decarbonization of the world's economy by 2100. Climate policy expert Jennifer Morgan of the World Resources Institute was in Germany for both sessions. and we asked her to explain these developments.

MORGAN: The G7 has decided that there should be decarbonization of the global economy over the course of this century, which basically means that you need to phase out fossil fuels in the coming decades. And they coupled that with a global emission reduction target that they would do their part, but they noted it needs to be global. And also they put out what they see as key priorities for the Paris agreements, and some important finance initiatives for developing countries as well.

CURWOOD: So, how big a deal is this action by the G7?

German Chancellor Angela Merkel took the lead in pushing the G7 to adopt this aggressive climate policy. (Photo: European Council, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MORGAN: I think the G7 signal that we need to decarbonize the world's economy in the coming decades is very significant. I think it caught many by surprise, including myself, that they were able to pull this off, and I think it comes from a number of things. I think number one is that Chancellor Merkel really took this on. She put the toughest issues on the G7 agenda, and she's personally committed. I think that she and President Obama worked very closely together with President Hollande, so you have a group of countries that do understand the risks and the need to send this kind of signal to investors around the world. And in Japan and Canada, I think in the end, the support around the world is growing and nobody wants to be isolated, especially when you're in the club of the G7. So there's a number of different factors that came together to make this happen, and now we need them to follow up on it.

CURWOOD: So over the years, from time to time you've worked with the German government, including the Chancellor Angela Merkel. How surprised were you that she decided to take this on?

MORGAN: You know, Chancellor Merkel's been a bit absent on the international climate stage for the last number of years, and I think this was her opportunity to get reengaged. I wasn't surprised that she took it on, and when she did, I kind of had this sense of confidence that it was all going to work out OK, because she is such an extremely committed scientist on all of this, and her negotiating skills clearly are quite good. So I guess I would just say that I'm just so pleased that she took the risk. She was the president of the first Conference of the Parties 20 years ago, and now she had the opportunity again 20 years later to make a difference, so we need her to stay engaged up until the last hours of Paris.

As economies phase out fossil fuels, solar energy is taking up an increasing share of the energy sector. (Photo: Deb Nystrom, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: By the way, in other European news, Norway has just divested its $890 billion sovereign wealth, its pension fund, from coal, that's nearly a trillion dollars. What you make of that?

MORGAN: I think that that is just a signal of what today is happening, that is along that global decarbonization of the world's economy. It signals to me that coal is no longer a viable investment, and certainly is something that should be removed from the portfolios of investors around the world.

CURWOOD: Of course, Norway makes a lot of its money from its own state oil company, StatOil.

MORGAN: It sure does, but I think this commitment was a very bold political statement by Norway, and does have economic consequences. I mean, they're going to have to change their portfolio, but it’s step number one.

CURWOOD: Now at the same time, one of the preliminary meetings for the November, December big deal in Paris has been going on in Bonn, a somewhat technical set of meetings, how they been going?

MORGAN: You know they've been pretty onerous, pretty slow. They're going through 90 pages of negotiating text and trying to make it coherent, get rid of brackets and various options, and they're doing that in large drafting groups. So it's slow, kind of like riding through mud, a bit, I think.

CURWOOD: By this time now, as part of the UN process, countries were supposed to say what their plans are to meet their own national targets. Which countries’ plans have particularly impressed you so far?

Deforestation in Gabon. The African nation is one of the countries that have submitted an ambitious emissions reduction plan in the lead-up to the Paris Climate Negotiations in the fall. (Photo: jbdodane, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

MORGAN: Well, I have to say, and it’s not just ’cause it's my own country, I think the US plan is pretty impressive. It has that 80% long-term target, so, not far off from what the G7 is advocating for, and it uses all the levers that the administrative executive branch has to reduce emissions in all the key sectors — power sector, transport, make our appliances more efficient —- so that's one that I think is pretty impressive. You know, the other one I think is really interesting is the country of Gabon that came out earlier, the first African country that tabled its national plan, and it focuses more on renewables and efficiency. But I think it is really important to see that all countries are figuring out what they can do to help save the planet from global warning.

CURWOOD: Now we just spoke with scientist Susan Natali about the threat of thawing permafrost to our climate. What do you make of the fact that, at least up until now, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a group of scientists, hasn't considered the permafrost issue in its predictions on climate change?

MORGAN: I find that really surprising. I would hope that in the next report that the findings of this research are included. They are stunning, they are shocking, and they have a big impact on, you know, what kind of response in the rate of change that countries need to put in place to avoid this type of impact. I think it also puts even more focus on getting those other emissions cut absolutely as quickly as possible, but then, also, you know, getting societies ready for some of these impacts. And that's a big issue in the climate negotiations from the poorest countries and the most vulnerable, that they want to see a focus on loss and damage. Which means, you know, what they lose and get damaged from the impacts of climate change and on adaptation. Because they need to be able to adapt to sea level rise and these types of impacts as best as they can.

Jennifer Morgan is the Global Director of the Climate Program at the World Resources Institute, and oversees the Institute’s work on climate change issues, guiding its efforts to help bring about a zero-carbon future. (Photo: WRI)

CURWOOD: Jennifer, before you go, tell me, how are you feeling now about the progress of negotiations towards getting a major deal in Paris in the fall — this G7 statement, these meetings in Bonn, the divesture movement?

MORGAN: I mean, I feel like we are making good progress. I feel like there are signals coming out from around the world, that they think this is the moment to be on the right side of history on this issue, whether it be this Norwegian commitment, whether it be the G7 commitments. And now the time is ripe for the negotiations to reflect that, to show the urgency throughout the negotiations and come out with something in Paris that really is a turning point, and sends those clear signals — not just from the G7, but from the whole world.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Morgan is Global Director of the Climate Change Program at the World Resources Institute. Jennifer, thank you so much for joining us once again.

MORGAN: Thank you.

Related links:

- The World Resources Institute statement on the G7

- Read a post from Jennifer Morgan analyzing what happened at the G7

- About the Group of Seven (G7)

- About Jennifer Morgan

[MUSIC: Imogen Heap, “Earth,” Ellipse, Megaphonic 2009]

Beyond the Headlines

Tim Horton’s Donuts, an iconic Canadian chain, is now embroiled in the battle between tar sands supporters and opponents, following its decision to stop running in-store video ads promoting pipeline company Enbridge. (Photo: Liam K, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s time now for Peter Dykstra to take us on a trip beyond the headlines. Peter is with the DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and he joins us today from College Park, Maryland. Hi, Peter. What’s up?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. Let’s go north of the border for a little bit of a surreal twist on the tar sands saga. It’s an ongoing, gloves-off political brawl that’s even drawn Tim Horton’s Donuts, the iconic Canadian chain, into the fight over one of Canada’s potentially most toxic exports.

CURWOOD: Well, I presume you mean the tar sands, and not the coffee and donuts.

DYKSTRA: Of course not. You don’t mess with Tim’s! With nearly 5,000 outlets all over Canada and the northern U.S., and for a time they even had one at the Canadian Forces outpost in Kandahar, Afghanistan. Tim Horton was a hockey hero, elected to the Hall of Fame a few years after he died in a car accident in the 1970s.

CURWOOD: So what’s up with the late Mr. Horton’s empire and the tar sands?

DYKSTRA: Well, many of those Tim’s outlets in Canada ran in-store video ads promoting Enbridge, the controversial tar sands pipeline company, but Tim Horton’s dropped the ads after a huge backlash and social media campaign from Canadians who love their Tim-bits — that’s what Tim’s called the little bite-size dough punched out of donut holes - but don’t love dilbit — the diluted bitumen that flows in a tar sands pipeline. Get it, Timbits, dilbit?

CURWOOD: Just keep going.

DYKSTRA: Well, after all this, tar sands supporters cried foul, and pro-tar sands protests began at Tim’s outlets in Alberta, Canada’s oil capital. So it’s on: petro-dollars versus donuts.

CURWOOD: Oh, Canada . . .

The EPA recently released a report on fracking and water supplies – but the study’s conclusions left ample room for both fracking supporters and opponents to spin them in their favor. EPA says while fracking has not yet had a significant impact on drinking water supplies, there is a significant risk that in the future it could. (Photo: Ángelo González, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Indeed. But let’s move on to a potentially teachable moment in what’s maybe an even more contentious issue. Last week, the EPA came out with a long-awaited report on the impacts of fracking on water supplies, and as you might expect, the report generated a lot of headlines. So let me read you a few headlines about whether or not EPA thinks fracking is a problem.

Here’s one: “Fracking has not had a big effect on water supply.” So, fracking’s not a big risk. But here’s another headline: “EPA finds drinking water vulnerable to fracking.” So, maybe fracking is a big risk. Another one: “Fracking study undercuts environmentalists’ call for more regulation.” Take THAT, fracking opponents, I’ve got your study right here.

CURWOOD: OK, Peter, so what did the EPA study actually find?

DYKSTRA: I’m glad you asked that, Steve. You know, we call this segment “Beyond the Headlines” for a reason. You’ve got to read beyond the headlines! These three stories, and many others, really report the same thing: EPA says there’s no current, smoking gun evidence that fracking has had a big impact on drinking water supplies. But there’s a significant risk that it could. Both fracking supporters and fracking opponents spun this study within an inch of its life. The reality is that it will likely change few opinions about fracking, but the most important takeaway here is: read beyond the headlines and make up your own mind.

CURWOOD: That’s always a good idea. Hey, let’s go to the history calendar. What do you have this week?

Twenty-seven years ago this week, the biggest fire season in Yellowstone National Park’s history began with a lightning strike. By the end of the fire season in 1988, 36% of Yellowstone had been scorched.(Photo: National Park Service, CC government work)

DYKSTRA: A little fire that became a big part of National Parks history. 1988 was a big drought year in much of the West, and on June 14th of that year, lightning set off a small fire near Yellowstone. Within a few weeks, a dozen more fires, fanned by fierce winds, merged into an inferno for America’s greatest national park. Big parts of Yellowstone burned all summer, in part because the Park Service policy was to let wildfires burn out naturally, with healthy ecological results.

CURWOOD: Yeah, but what played out on the nightly news were pictures of Yellowstone being destroyed forever, it seemed, while the Park Service looked like the Emperor Nero.

DYKSTRA: Right, and that was unfair to the Park Service and to firefighters. From a tourism standpoint, Yellowstone was trashed for a few years. From an ecological standpoint, the fire was part of an essential, recurring process that renews wildlands. When you suppress fires artificially and deadwood and brush build up, you’re only making the next fire worse.

CURWOOD: Yes, and Yellowstone has nicely recovered. Thanks, Peter Dykstra! Peter is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN dot org, and The Daily Climate. Talk to you next time.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot, we’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE dot ORG.

Related links:

- Fracking Has Not Had Big Effect on Water Supply, E.P.A. Says While Noting Risks

- EPA finds drinking water vulnerable to fracking

- Fracking Study Undercuts Environmentalists’ Calls for Regulation

- EPA fracking study

- Video: The Story Behind the Yellowstone Fires of 1988, The New York Times

- History of Wildland Fire in Yellowstone

[MUSIC: Leon Redbone, “Baby Won’t You Please Come Home,” Boardwalk Empire Volume Two Music From the HBO Series, ABCO 2013]

Chimps Like To Cook

Chimpanzees prefer their food cooked, are patient enough to cook it, and understand that a transformation happens during the cooking process. (Photo: Alexandra Rosati)

CURWOOD: We humans like to think we're special, but as we learn more about other creatures, the difference between us and some of them becomes harder to pin down. For example, we know that prairie dogs have a surprisingly complex system of communication, and elephants mourn their dead. And, as a team of scientists recently discovered, chimpanzees can cook! Well, sort of. To learn more about this primate talent and what it may tell us about our own evolution, we called up Felix Warneken, Associate Professor of Psychology at Harvard, who conducted the study with his wife, Alexandra Rosati. Felix Warneken, welcome to Living on Earth.

WARNEKEN: Yeah, thanks for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, first of all, what inspired you to do this experiment?

WARNEKEN: The inspiration came from a really provocative hypothesis by a Professor Richard Wrangham who is also at Harvard. And he has written several papers and a whole book, actually, that's called “Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human,” where he shows that cooking is an important aspect of human evolution, because we have these large brains that are metabolically or energetically very expensive. So we somehow have to find the energy to sustain them. And what he proposes is that cooked food will be digested by us more easily, and we can gain more energy from it, and therefore we have much more energy available — that we can use, for example, for sustaining these large brains. So, this was the hypothesis that we started out with, and what my colleague Alexandra Rosati, and I thought was that we can maybe add to this debate about when it was possible for humans to cook their food by studying chimpanzees.

CURWOOD: So of all the primates you could've chosen for the study, why did you pick chimps?

Felix Warnecken and Alexandra Rosati, his wife and colleague, didn’t train the chimps in their experiment to cook. Given a ‘magic cooking device’ they had never seen before, the chimps learned the cooking concept on their own. (Photo: Alexandra Rosati)

WARNEKEN: So, chimpanzees are interesting for studying human evolution because they're one of our closest evolutionary relatives. And so the logic is that, because we're so closely related, that whatever you find in both humans and chimpanzees probably existed already in the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees, living five to seven million years ago. So this is why we studied chimpanzees — to see to what extent several of what we believe are critical capacities to cook food are already present in these chimpanzees as well.

CURWOOD: Well, I have to tell you, you know, there’s been all this talk about how important it is to eat raw food, so, by the way, I'm really grateful for your study because I can feel more comfortable eating cooked food now!

WARNEKEN: [LAUGHS] That's right. So, I mean, this is what I would highly recommend, reading this book by Richard Wrangham. It's really quite amazing because here he details that there are no humans around that would survive on purely raw, unprocessed food at all. Because we can't extract the energy that we need from it, and that is one major difference — the chimpanzees actually can. So in other terms, we wouldn't be able to sustain on a chimpanzee diets on what chimpanzees in the wild eat on a regular basis. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Thank heavens for that. I'm not sure I want to try the chimp diet!

WARNEKEN: [LAUGHS] No, no.

Chimpanzees are more socially aggressive and less cooperative than human beings. This competitive spirit may be one of the reasons chimps never evolved to cook their food. (Photo: Alexandra Rosati)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] So, Professor, please walk us through your experiment.

WARNEKEN: Yeah, so what we did is have a whole series of studies to probe chimpanzees’ abilities to cook food. And so what we started out with was asking, what are the kinds of things you have to be able to do in order to cook food? One of the things, is, obviously that you have to be motivated to do it, so we checked that chimpanzees actually prefer their food cooked. So what we did was we focused on white sweet potatoes, because that is something that the chimpanzees that we tested in the center in Africa eat on a regular basis, and they like it. But then we see if they like it even more when it's cooked. And we found, yes, that is the case. If you give them a choice to receive a slice of raw potato versus a slice of cooked potato, they prefer the cooked one.

So that was our first experiment, and then the second issue is that for cooking, obviously, you need more patience, because you could eat the raw version of the food immediately. In order to cook it, however, you have to wait some time. And so that was our second experiment. We tested whether chimpanzees, when they see that they would receive a cooked food, would wait even longer for that, and that was the case as well.

Although we have many differences, chimps also share striking similarities with human beings. 98.8% of their DNA is the same as ours and we share a common ancestor. A new study shows they also use smiling for communication. (Photo: Alexandra Rosati)

And then, when you think further, what else do you have to know and be able to do to cook food is that you have to, somehow, understand, at least on a practical level, that there is this kind of transformation from something raw to something cooked. And so what we did to test this is that we invented this “magic cooking device.” So it's just a bowl, basically, and we showed that when you put a raw slice of potato in it, close it with a lid, shake it, and open it again, it comes out cooked. We use a false bottom to do that, and the reason for doing that was that, first of all, it would've been a bit too dangerous for us to have an actual camping cooker or some other kind of thing in front of these chimpanzees. Imagine them grabbing onto a gas tank — that would not be fun, so that was one reason, just practical. And the other reason is that these chimpanzees may have seen humans using fire to cook food because they live at the center where they see humans all the time. And so, because we're interested in their simultaneous ability to make these inferences, we presented them with this completely novel device that they had never seen before. And so, if chimpanzees understand that, it seems like their understanding goes deeper than just some observation of what they have seen before.

CURWOOD: So they understood that this was a cooking device, it sounds like?

WARNEKEN: That's right. So what they saw was us putting a slice of potato in, and then it comes out cooked, and within minutes, within a single session, when we gave them the choice to receive food after it had been placed and manipulated with this cooking device versus a control device — that was basically a broken cooker that was something that did not change the food that you put into it — they would reliably point to the cooking device, and wanted to receive the food from the cooking device over this control device.

CURWOOD: Now, Professor, I have to ask you at this point — why not just use a microwave for this cooking experiment? I mean, chimps reliably can be trained to push a single button.

WARNEKEN: The simple issue with this is that there's no electricity where we ran our experiments, so putting up a microwave would have been a little bit of a problem, and it also really doesn't fit our luggage that we have to haul over to Africa every summer here from Cambridge. But that is basically what it is, and that would be a really cool study, I agree, to see whether they would do that. I think they would succeed at it, like you say, I think one important aspect is the question to what extent they need to be trained to do it, or they just can figure it out by themselves. But what was so striking to us was that this chimpanzees picked up on these things so quickly.

Chimps aren’t afraid of fire; they’ve actually been known to monitor bush fires in the savanna and eat seeds cooked by the flames. Scientists believe they haven’t mastered fire like humans because, unlike us, chimpanzees don’t pass down a wealth of knowledge from one generation to the next. (Photo: Doug Beckers CC BY-SA 2.0)

So we really didn't train them to do this stuff. We gave the chimpanzees raw slices of potato, and then offered them to put it into this cooking device, or this control device, or just eat it. And then, to our amazement several, of these chimpanzees would actually place the food into this cooking device, they would shake it, open it, and then they would receive the cooked version of it. And it was really surprising to us, because chimpanzees usually eat what they can get. It requires a lot of what is called “inhibitory control” to resist the temptation to just eat something that you hold in your hands, but place it into something so that it turns into something even better.

CURWOOD: So what do you think chimps being able to cook tells us about us?

WARNEKEN: So I think what it tells us is that, at least in principle, our human ancestors possessed several of the abilities that are necessary to cook food. Obviously, chimpanzees do not have all the abilities that are necessary, because chimpanzees in the wild do not actually cook food. So that leads to the question: what are the other things that are necessary? And so, one important thing is the control of fire, that you have to find some way of using that. And chimpanzees do not do that, at least not in the wild, and so this may be one reason why we see this only in the human lineage and not in chimpanzees, cooking. But another reason is maybe more social. Chimpanzees are very competitive over food, and so if you are in a group of individuals competing over food, the best choice for you may be to just eat whatever you have, right, because that lowers the risk of losing it. For humans, early humans, also to cook it maybe required that they were more trusting towards each other, and respecting each other's ownership over food.

CURWOOD: So your studies suggest that we humans aren't all that different from our close relatives?

Warneken and Rosati conducted their experiments in the summer of 2011 at Jane Goodall’s Tchimpounga Chimpanzee Sanctuary in the Republic of Congo. (Photo: Kris Snibbe/Harvard University)

WARNEKEN: Yeah, so what is really striking when you look at this, at the whole field of what is called “comparative psychology,” you find that there is so many things that we previously thought to be unique to humans that have, at least, really striking precursors in chimpanzees. So I think what is apparent on the one hand is we are obviously really different, but then there's so many components that you see already in chimpanzees that indicate to us that maybe it required putting all these components together that made us human, rather than that there's this one single magic thing that is different between humans and chimpanzees that explains all the various differences that we see.

CURWOOD: Felix Warneken is an Associate Professor of Psychology at Harvard University. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

WARNEKEN: Yeah, thanks.

Related links:

- Study Published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B

- NY Times Book Review of “Catching Fire” by Professor Richard Wrangham

- Tchimpounga Chimpanzee Rehabilitation Center

- Chimpanzees and humans share 98.8% of their DNA

- Chimps communicate by smiling like humans

BirdNote®: Bird Song, Music, and Neuroscience

Scientists at Emory University wanted to know whether a bird experiences a song from its own species the way we experience music. (Photo: Ken C. Schneider)

[MUSIC: BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: It may not be a surprise that our close primate relatives seem to have cognitive responses and understanding that is parallel to ours. But as Michael Stein explains in today’s BirdNote®, we seem to be on many of the same pages with our feathered friends, at least when it comes to song.

BirdNote®

Bird Song, Music, and Neuroscience

STEIN: Scientists at Emory University have taken a novel approach to a question that's hung in the air for millennia: how are music and bird song related? The new approach puts the question this way: looking at what happens in the brain, does a bird experience a song from its own species the way we experience man-made music? Brain imaging studies have shown that hearing enjoyable music lights up what's called the mesolimbic reward pathway in the human brain. The study reveals a very similar pattern in the sparrow’s brain. Female White-throated Sparrows, hormonally charged for breeding season, were played songs of male White-throated Sparrows.

[White-throated Sparrow song]

Just as in humans, the mesolimbic reward pathway lit up. You might say the sparrows were, at the neural level, turned on by the songs of a potential mate.

The same reward pathway that lights up when humans wear music also lights up when female white-throated sparrows hear a male’s call. (Photo: Putneypics)

[White-throated Sparrow song]

Not so with male sparrows, though. Hearing the song of another male triggered the part of the brain similar to the one that lights up when humans hear horror film music.

[Music]

For a male sparrow, when he hears the song of a potential breeding rival, there's a lot at stake.

[Music]

I am Michael Stein.

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. White-throated Sparrow song [169021] recorded by Matthew D Medler.

Music 'Le Merle Noir' by Olivier Messiaen performed by Matthew Schelhorn and the soloists of the

Philharmonia Orchestra.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Dominic Black

© 2015 Tune In to Nature.org May 2015 Narrator: Michael Stein

References:

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/01/science/birds-found-to-have-emotional-reactions-to-song.html?smid=fb-share&_r=0

http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnevo.2012.00014/full

White-throated Sparrow male - Putneypics https://www.flickr.com/photos/38983646@N06/8690345201

White-throated Sparrow tunes up - Ken C Schneider https://www.flickr.com/photos/rosyfinch/4535903592

http://birdnote.org/show/birdsong-music-and-neuroscience

CURWOOD: You can find pictures if you hop on over to our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- Listen to this week’s BirdNote®

- About the white-throated sparrow

CURWOOD: Coming up: the story of naturalist and Sierra Club founder John Muir, set to music. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

New Music Brings John Muir's Story to Life

Violinist Liesel Wilson, left, is a frequent collaborator with Ed Willett and Cheryl Leah of musical duo “Chance.” Along with actor Thomas Clyde Mitchell, the musicians recently created a performance called “John Muir: University of the Wilderness.” (Photo: George Eggers)

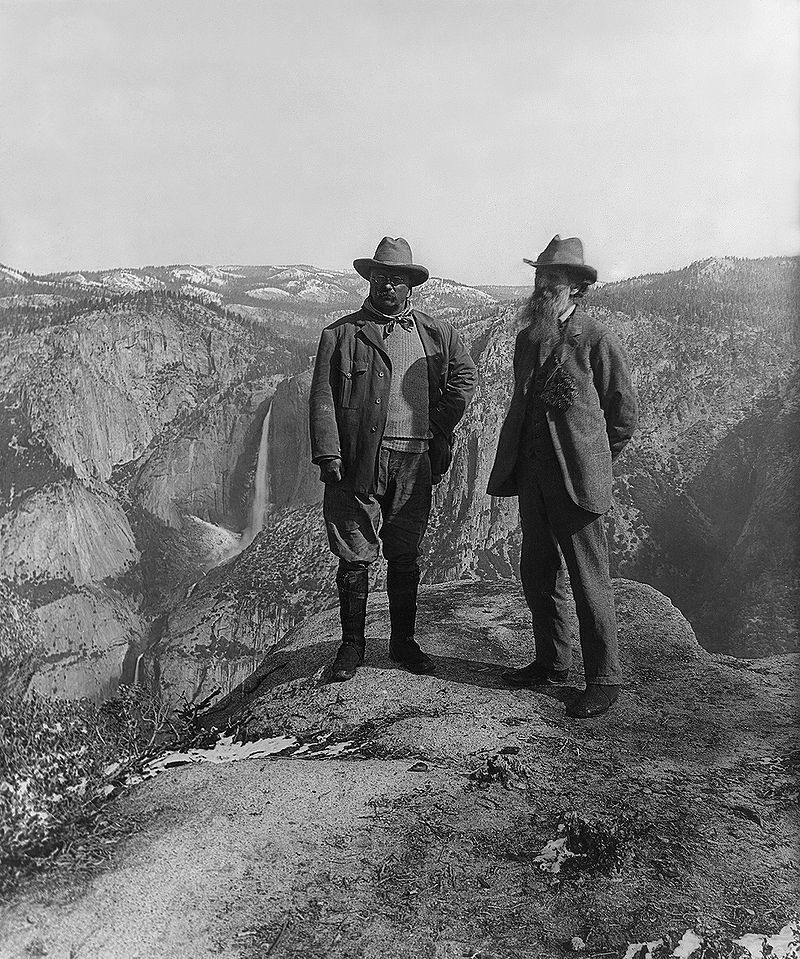

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Of all the figures that helped shape an early appreciation for the American landscape, John Muir is among the most iconic. Muir’s mission in life was the protection of wilderness, and the founder of the Sierra Club is credited with inspiring President Theodore Roosevelt during a camping trip in Yosemite to start the National Park System. Today, the landscape of the country shows Muir’s legacy — with the John Muir hiking trail, Muir Glacier, Mount Muir, Muir Woods. And the June 13th dedication of new lands at Muir Park, including the Muir homestead in Wisconsin, provides the quartet “Chance” the occasion to celebrate John Muir in music. Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer prepared this report.

MITCHELL: “My ancestors must have been born on the Scottish moors, for there is heather in me, and tincture of bog juices oozing through all my veins.”

In the “narrative concert,” actor Thomas Clyde Mitchell reads the writings of John Muir, which are woven into the musical score. (Photo: George Eggers)

PALMER: John Muir was a child of Scotland, and in this narrative concert, composer Ed Willet uses the conservationist’s own words to tell his story.

WILLETT: The writings of Muir are performed by an actor who’s part of our troupe. We decided to do it in a chronological setting; we start off in his early days in Scotland.

MITCHELL: “After I was five or six years old, living in Dunbar, Scotland, I ran away to the seashore or fields every Saturday. Oh, the blessed enchantment of those Saturday runaways in the prime of spring. Those were my first excursions; the beginnings of lifelong wanderings.”

PALMER: Actor Tom Mitchell plays Muir and doubles on percussion, along with Liesel Wilson on violin, Cheryl Leah who sings and writes some of the lyrics, and Willett on the cello. After John Muir’s early days wandering the Scottish moors, the action and the family move to Wisconsin, when they emigrate.

MITCHELL: “America! We settled in the Wisconsin wilderness a few miles from Portage in a sunny woods overlooking a pond which Father named Fountain Lake. Father put me to the plow at the age of 12, when my head reached but little above the handles. For many years I had to do the greater part of the plowing.”

Muir Park is a 150-acre State Natural Area in Wisconsin, and includes the Muir homestead, settled by John Muir’s father Daniel in 1849. (Photo: Aarongunnar, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

PALMER: But the back-breaking work on the farm wasn’t enough to keep young John Muir down — from his earliest days he was also a tinkerer, who liked to know how things worked, and tried to invent something better.

WILLETT: They were inventions like clocks, and one alarm clock that was rigged up to a device that would raise the top half of his bed, so it kind of threw him out of bed, if you could imagine that. He’d always had that kind of a mind. It started very young for him; in fact, he would get into a great deal of trouble with his father when he was eight years old because he was working on his inventions all the time, and that wasn’t something that his father thought was a good use of his time. So he finally got his father to agree to let him start his day whenever he wanted. So instead of getting up at five o’clock to start working, he would get up at two o’clock in the morning, one o’clock in the morning, and go down in the cold basement and work on these inventions.

John Muir’s legacy includes the designation of Yosemite as a National Park, the founding of the Sierra Club, and the introduction of Americans to their public lands. A prolific writer, Muir produced numerous articles and several books that conveyed the wilderness of the American West to distant readers. (Painting by Colleen Mitchell-Veyna, used with permission)

PALMER: This creativity paid off for Muir; it was the door to formal education — though, as he writes in his autobiography “The Story of My Boyhood and Youth,” which is the source of the words Willet sets, formal education wasn’t enough.

MITCHELL: “I was told by neighbors I should take my inventions to the state fair in Madison. There it was considered wonderful that a boy on a farm had been able to invent and make such things. These inventions opened all doors to me, including Wisconsin University, where I studied for four years before wandering off on a glorious botanical and geological excursion, leaving one university for another, the University of the Wilderness!”

PALMER: “John Muir — University of the Wilderness” is the title of this work, and Muir’s upbringing prepared him for that education, says Willett.

WILLETT: His father was a task-master and disciplinarian, and apparently Muir regularly saw the other end of a belt for little provocation. It was so rough, but it seemed like it possibly had a lot to do with why he ended up seeking a sanctuary in nature, and why he was able to be so resilient to being in the mountains for three weeks and all the things he did — walk a thousand miles, as he did in the United States.

When President Theodore Roosevelt visited Yosemite National Park in 1903, it was John Muir who showed him the park and lobbied for additional protections for Yosemite. Thanks in part to Muir’s persuasion, President Roosevelt protected approximately 230 million acres of public lands during his presidency. (Photo: Mfield, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

MITCHELL: “I began by walking to the Gulf of Mexico, a thousand miles, more or less, then decided to visit California and see its famous Yosemite Valley. As I arrived on the steamer in San Francisco, a man on the wharf asked where I was bound. ‘Anywhere that is wild!’ I set out again afoot, and soon came to the great Central Valley, like a flowered lake of pure sunshine. From its eastern boundary rose the mighty Sierra, so radiant it seemed not clothed in light but wholly composed of it. I was a new creature, born again, and truly until this time was I fairly conscious that I was born at all!”

PALMER: That experience in California was a revelation for Muir. He’d been observing the natural world and meticulously noting its every detail since his childhood in Wisconsin.

MITCHELL: “Our beautiful lake, named Fountain Lake by Father but Muir’s Lake by the neighbors, is one of the many small glacier lakes that adorn the Wisconsin landscapes. It is fed by 20 or 30 meadow springs, about a half mile long, half as wide, and surrounded by low, finely-modeled hills dotted with oak and hickory, and meadows full of grasses and sedges and many beautiful orchids and ferns.”

The John Muir Trail, or JMT, travels 211 miles through the High Sierra, Muir’s stomping ground. The trail begins in Yosemite Valley and ends at the summit of Mt. Whitney, the highest point in the Lower 48. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

PALMER: Ed Willett grew up near the Muir homestead in Wisconsin. He says he and Cheryl Leah combed through dozens of Muir’s books and articles to find just the right inspiration for their original music and lyrics.

WILLETT: We decided that we wanted to have our program be more of a philosophical landscape than a historical one. Most of it is sort of trying to get into his emotion again, trying to get an insight into what makes a person be so passionate and be such an inspirer of others.

PALMER: His writings inspired Willett and Leah to write Roses in the Hollow, a picture of Muir immersed in the profusion of life and its early summer flowers.

VOCAL MUSIC: [Roses in the Hollow, Roses in the Hollow…]

WILLETT: Roses in the Hollow is one of the middle movements. The roses are an archetype and it’s a picture of life that we see often in the springtime and in the early summer. I tried to put into the music the myriad of directions that life is going at the same time.

PALMER: But this musical piece doesn’t just show Muir reveling in the lushness and bounty of summer, it captures his other qualities as well.

Garnet Lake, shown here reflecting Banner Peak and Mt. Ritter at dawn, is one of the more spectacular spots on the John Muir Trail. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

WILLETT: One of the things that fascinates me about him is his adventurer spirit. We think about him writing at a writer’s desk often, because that’s what we see of him, but he was an amazing risk-taker. He was a mountaineer, and in fact there’s a piece based on the writings that he wrote about an experience on Mount Shasta in the western United States, where he was trapped on a mountain overnight and near death, and ended up staying warm enough on some hot fumaroles, they’re called, hissing fumaroles, the warm air that comes up from volcanic depths. And so, he and his partner spent the whole night trying to survive this storm and they barely did. And at the end of that adventure we have a piece, actually, that’s sort of his homecoming. When he gets to the end of that adventure and they are stumbling down the mountain and they get back to camp, this piece called “Night Step Softly” comes in. And to me, it just represents the relief that someone gets when they’ve done something amazing and just cheated death again, and then they get to sleep.

MUSIC: Sleep now, angel, let this day be through. Let all but what you’ve gained from love fall and fade from view. And I’ll steadfast, be watching over you. Sleep now, angel, sleep.

Muir Pass, a forbidding, high-altitude mountain pass backpackers must climb on the JMT, is the site of the John Muir Memorial Shelter, built in 1930 by the Sierra Club. The sturdy stone hut functions as an emergency shelter for hikers caught in stormy weather. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

PALMER: You obviously have a tremendous fondness for Muir as a character, as an icon.

WILLETT: Yeah I do, I guess it’s pretty deep with me because just the other day I dug up some writings of my own father, who was a naturalist and patterned a lot of his life after Muir, who was an environmentalist. The parallels between my father’s writing and Muir’s were just arresting. I hadn’t really noticed it quite as much, but I was digging through some old writings of his. So I think it goes right from the ground up for me, for sure.

PALMER: And the music in “John Muir — University of the Wilderness” is not just about the man, but also the writing that speaks so directly and intensely, and the life dedicated to keeping wild and beautiful places pristine and protected for everybody. For Living on Earth, I'm Helen Palmer.

[MUSIC FROM “JOHN MUIR — UNIVERSITY OF THE WILDERNESS” BY CHANCE]

Related links:

- The narrative concert, “John Muir -- University of the Wilderness”

- Muir Park State Natural Area

- John Muir’s writings

- About John Muir

- The protection of additional Muir family farm acres

The Place Where You Live: East Claridon, Ohio

Fog blankets the pond where Anne Kelsey spends sacred mornings in her kayak. (Photo: Anne Kelsey)

CURWOOD: From Wisconsin to Ohio now, for another installment in the occasional Living on Earth “Orion Magazine” series, “The Place Where You Live.” Orion invites readers to submit essays to the magazine’s website and put their homes on a map, and we give some of them a voice.

[MUSIC: Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros, “Home,” Up From Below, Community Music 2010]

KELSEY: My name is Anne Kelsey. I live in St Louis, Missouri. I wrote my essay about our family place in East Claridon, Ohio. We've had it for almost 100 years. My grandfather bought it a long time ago, and it was used as a summer place until my parents built a house on it. We've had a lot of family events there — weddings, birthdays, anniversaries. My father died there. It's wooded. It's got a large pond, about a 35-acre pond in it, and a lot of wildlife. And then, about 15, 20 years ago maybe, I got this tiny little kayak, and I started going out on the water. It's quite magical and some of the residents of the pond are probably as old as I am. There's some huge snapping turtles that are quite scary when they go underneath the kayak. They look like dinosaurs. In my kayak, I learned how to be extremely silent. It's really become a form of prayer, where I'm just aware of the fullness and beauty of creation.

Turtles sun themselves on an old plank in the pond. (Photo: by Anne Kelsey)

This is my essay about East Claridon, Ohio.

The night sky softens to a deep calm grey before the first blush of dawn turns robust and the moon fades to a transparency. From the branches of a hemlock a black-capped chickadee drops two clear descending notes, as confident as the first violin of an orchestra.

[CHICKADEE SONG]

A wood thrush sends out a flute-like whistle.

[THRUSH SONG, FOLLOWED BY CARDINAL AND ROBIN]

A cardinal and then a robin follow, then the air is filled with an assortment of cheeps, trills, chirps, clacks, fillips, screeches, twitters and whistles.

Water Lily. (Photo: by Anne Kelsey)

[SOUNDS OF DAWN CHORUS]

Even to an untrained ear unable to match the call to the bird, they sound different, one from another. Each note encourages another, and one by one, the winged residents of pond and woodland take up an invitation to sing a lively morning cantata.

Cow lilies raise sturdy fists of yellow buds above the water. A small flock of Canada geese takes to the air, rising hard and fast . . .

[GEESE CALLING]

. . . calling furiously to each other above the rounded contours of the pond, where an old snapping turtle rests in the mud. Water spills over an old brick dam and provides background music, always changing its tune. On the hottest days of August, after weeks without rain, it becomes a whisper.

A spotted sandpiper. (Photo: courtesy of Anne Kelsey)

A beaver swims from its humped, muddy house, in search of new green leaves. A raccoon picks her way along the shore, in the deep shadows of pine and beech. As the light brightens and the air warms, a couple of turtles line up on a fallen log. Pink and white water lilies begin to open. Another morning comes to Blue Heron Farm.

It isn’t really a farm at all. It’s family land we’ve hung onto for almost a hundred years, and now the only harvests are memories and love of the land. As miles go, I live far away, but at night, when I can’t sleep, I imagine waking up to the sight of a blue heron gliding across the pond and morning birdsong. In my heart and imagination, this is my real home.

[MUSIC: Kaki King, “Night After Sidewalk,” Everybody Loves You, Velour 2003]

KELSEY: As I said, my grandfather bought it, and now it's part of my mother's estate and I have four younger sisters, so there are five of us with all kinds of different financial needs and emotional attachments to the place and so, unless I win the lottery, we do have to sell it. It will be a huge grief when it finally passes from our hands, although we don't own the land. We are just stewards of the land, we are caretakers, so I just hope that it will pass onto someone who understands land in the same way.

Snapping Turtle on a branch. (Photo: courtesy of Anne Kelsey)

CURWOOD: That’s Anne Kelsey and her essay about her holiday home in Ohio, and you can tell us about “The Place Where You Live,” if you like. There’s more about “Orion Magazine” and how to submit your essay at LOE.org.

[MUSIC: “NIGHT AFTER SIDEWALK,” KAKI KING, EVERYBODY LOVES YOU, 2002]

Related links:

- Read Anne Kelsey’s original essay at Orion Magazine

- Read more from Orion Magazine

- Listen to more The Place Where You Live essays

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth: the quest to save the saola, a species so rare and remarkable, they call it the ‘Asian Unicorn.’

DEBUYS: When the saola stands profile, the two horns, in perspective, merge into one, and it appears to be a unicorn.

CURWOOD: This unicorn’s not mythical, but it could be gone before science can catch up with it. That’s next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Artie Traum, “Golden Gate Fog,” Meetings with Remarkable Friends, Narada Productions 2006]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Shannon Kelleher, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, James Curwood, and Jennifer Marquis. Our show was engineered by Tom Tiger, with help from Jake Rego, Noel Flatt, John Jessoe and Jeff Wade. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org — and like us, please, on our Facebook page — it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth