January 12, 2018

Air Date: January 12, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Costliest Disaster Year Ever

View the page for this story

US natural disasters in 2017 cost $306 billion, the most expensive year since NOAA started keeping tabs in 1980. For a closer look at how the year's weather events resulted in such high damage costs, Host Steve Curwood turned to Kendra Pierre-Louis – a Climate Desk Reporter for the New York Times. (06:30)

Offshore Drilling Under Fire

View the page for this story

The Trump Administration’s plans to open up nearly all the US outer continental shelf to offshore drilling drew sharp bipartisan criticism. When US Interior Secretary Zinke exempted Florida, lawmakers from several other coastal states then asked for similar treatment, but no answers so far. Steve Kretzmann of Oil Change International explains to host Steve Curwood about why there’s such widespread opposition to offshore drilling, and how it risks not only spills but also the health of the entire planet. (07:20)

Nature, The First Best Teacher

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Nature-based preschools, where children spend most of their day outside, are a growing trend in the United States. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports from a school in Chester, New Hampshire that kids who learn outdoors have better academic results – including higher scores on standardized tests – while they learn to love the outdoors and have fun. (08:53)

Bitcoin, The Energy Hog

View the page for this story

With a net value estimated at some $250 billion, Bitcoin has become the world’s premier virtual currency. Although it exists only online, it runs up huge energy costs in the real world. Data consultant Alex de Vries explains that verifying Bitcoin transactions is so energy intensive, the currency tops 159 individual countries in energy consumption. He and Host Steve Curwood explore Bitcoin’s climate costs. (07:01)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood discuss a rebuke to the Trump administration’s efforts to prop up coal and nuclear power, and a controversial deal to allow a road through an Alaskan wildlife refuge. In environmental history, the two remember an agreement to disclose toxic chemicals in industrial settings, and how the events of 9/11 derailed that transparency. (04:49)

Saving Trees That Helped Save Dust Bowl America

View the page for this story

The Great Plains were the nation’s breadbasket, but drought in the 1930s created the Dust Bowl. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s solution was to plant trees as a shelterbelt to help hold back the dust. The plan worked, but now some farmers, forced by economic necessity to maximize crop yields, are cutting them down. Journalist Carson Vaughan of the Food and Environment Reporting Network joins Host Steve Curwood to examine the country’s increasingly vulnerable great wall of trees. (12:13)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Kendra Pierre-Louis, Steve Kretzmann, Alex de Vries, Carson Vaughan

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. 2017 was only the third hottest year on record in the US, but at 306 billion dollars, disaster damage broke all records.

PIERRE-LOUIS: When you go back to 1980 when they first started keeping records, there were only 3 natural disasters that topped a billion dollars. This year it was 16. The only other year where there are 16 events that topped a billion dollars was in 2011. So what we're seeing is it's not just that we're having severe weather events, we're having more of them.

CURWOOD: Also, the benefits of nature as the classroom.

LOUV: Many people have standing desks and all of that and yet our children are still sitting in the school room and we are cutting recess, and this goes against decades of research that show physical activity stimulates cognitive functioning. It improves physical health. It makes better students.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Costliest Disaster Year Ever

Fires ravaged parts of Southern California in December 2017, unusually late for fire season. (Photo: Henry Garvin / Los Angeles Fire Department, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. NOAA – the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – tells us America suffered a record amount of damage in 2017 from natural disasters, with a tab of more than 306 billion dollars. And to put that 306 billion in perspective, consider that it’s more than the interest on the US national debt, and twice the federal budget for health, Medicare, and education. Extreme weather hit almost every state this year: wildfires out west, Hurricanes Irma, Maria and Harvey in the South, and disasters that got less press coverage but still cost of over a billion dollars -- events like the Minnesota hailstorm and drought in the mid-west. Here to discuss these steep costs and how they relate to climate disruptions is Kendra Pierre-Louis from the New York Times Climate Desk. Welcome to Living on Earth Kendra!

PIERRE-LOUIS: Thanks, Steve. I'm so glad to be here.

CURWOOD: So, $306 billion dollars. Just how unprecedented is this figure record-wise compared to previous years?

PIERRE-LOUIS: Yes, it's record-breaking. The next closest disaster year was in 2005, and that was the year of Hurricane Katrina and that was $91 billion dollars less.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, we're not saying that climate caused all of this, but climate amplifies these disasters.

PIERRE-LOUIS: Right. We can definitely say that climate change amplified these disasters, and that we can see especially when it comes to, like, the western fires or the hurricanes that happen this year, we can definitely see the fingerprints of climate change. Researchers found that when it came to Hurricane Harvey that 38 percent of the rain can be attributed to climate change. That means in some places where as much as 50 percent of the rain fell, almost 20 of those inches you can blame on climate change.

The aftermath of the Tubbs Fire, the most destructive wildfire in California’s history, which destroyed parts of Napa, Sonoma, and Lake Counties in the Northern part of the state. (Photo: David Welch, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, what kinds of natural disasters account for the largest portion of these costs?

PIERRE-LOUIS: Hurricanes account for the largest portion of these costs, but it was also the most costly fire year on record as well. And then when you start digging into the data it's just the sheer number of incidences. When you go back to 1980 when they first started keeping records, there were only three natural disasters that topped a billion dollars. This year it was 16. The only other year where there were 16 events that topped a billion dollars was in 2011. So, what we're saying is it's not just that we're having severe weather events. We're having more of them.

CURWOOD: It seems that there are many disasters that cost a billion dollars or more that didn't surface in the national consciousness in a big way this year, but nonetheless had a fairly staggering impact collectively. Talk to me about some of those.

PIERRE-LOUIS: Sure, you have the Missouri and Arkansas floods and severe weather. That was $1.7 billion dollars. You have hail storms and high winds in Texas, Oklahoma, Tennessee...that was $2.6 billion dollars. One of the ones that I think did not get a ton of attention was the drought, for example, in South Dakota, North Dakota and Montana. And droughts are really tricky because there are so slow moving that we don't notice them. But for the farmers who it impacted, a lot of them like cattle ranchers, it caused them a tremendous lot of financial loss.

CURWOOD: Talk to me a bit more about how climate change may have aggravated all this damage.

PIERRE-LOUIS: Yes, so it was unusually warm across the country. NOAA came out with that release the same day they came out with the disaster data, and so it's a threat multiplier. A really good example is the hurricanes. The oceans were warmer than usual, so that warm water fed the hurricanes. The wildfires out west, California was wetter in the winter and then it was really really dry, so all of that moisture created a ton of grass that grew really quickly, then the grass died off because it was so dry and then when the fire started it fed on all of that dry grass, and so that was all amplified by climate change.

A hailstorm in Minnesota racked up $2.4 billion in damage for the state. (Photo: Stevesworldofphotos, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: And how does 2017 figure on warming ... on the warming record?

PIERRE-LOUIS: It's the third warmest year in the United States on record. The global data isn't out yet, but it should be out next week.

CURWOOD: So, things are really heating up.

PIERRE-LOUIS: Yeah, the Earth has a fever.

CURWOOD: How are insurance companies dealing with this? How much of the damage are they paying for?

PIERRE-LOUIS: A lot. This was a very expensive insurance year. It was the most expensive disaster year on record for insurers according to Munich RE, one of the world's largest reinsurers. They're recently the insurers of insurance companies. A lot of it was fueled by the disasters in United States, but there was also significant flooding in Asia. Obviously, what they're going to do is they're going to start passing those costs on to people. So, if you're living in places that are at high risk for flooding or high risk for fires, you're going to end up seeing increased costs because that's the only way that they're doing it. The one exception is in Florida because a lot of Florida flooding insurance and hurricane insurance is backed by the federal government. So, actually taxpayers are on the hook for those costs, and so there's going to be sort of a reckoning when it comes to Florida about how they handle the insurance.

CURWOOD: Beyond the bottom line, what kind of toll is this taking on people's psychological well-being?

Kendra Pierre-Louis is a Climate Desk Reporter for The New York Times. (Photo: Courtesy of The New York Times)

PIERRE-LOUIS: There was a study that basically suggested that when these kinds of disasters happens, it's actually really psychologically traumatic because not only do you lose your home in many cases, but you also lose your social connections, you don't have your neighbors, you don't have this breadth of support system. How you’ll deal with it really depends on whether it's the first time you've gone through this or if it's multiple occurrences. But basically it's really traumatic and that's ignoring, for example, the death toll rate. Like, if you've lost a loved one in one of these disasters that's obviously going to be even permeate even further.

CURWOOD: So, does it get worse the more times you go through it or do you become more resilient...you say, ‘Oh all right, here it is again.’

PIERRE-LOUIS: It seems like people get worse. The one researcher that I talked to that looked at the flooding in Lafayette, I believe in 2016, said that after the rains happened in Lafayette the children whenever it rained a little bit too hard, the children would freak out. They really thought they were going to lose their homes again, they thought the floods were coming back. They really didn't know how to deal with it.

CURWOOD: Kendra, what's the lesson that we should be taking from this?

PIERRE-LOUIS: The lesson is two-fold. The first is that we should be taking steps to reduce the amount of carbon emissions that we're releasing into the atmosphere so we can stave off the worst effects of these natural hazards. The other thing is we need to go deep into planning for the future, which is to accept that these kinds of occurrences are more likely to happen. When you look at Harvey in particular, we have people who are moving into flood zones, moving into places that were designed to flood and so it's hard to say that that's natural, right? We need to think really through in terms of where we are putting our communities and how we're planning our communities, so that we are more resilient when these kinds of weather events happen.

CURWOOD: Kendra Pierre-Louis is a Climate Desk reporter for The New York Times. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

PIERRE-LOUIS: Thanks so much for having me.

Related links:

- Kendra’s New York Times story on the damage costs

- NOAA’s original report

- See how 2017’s disaster costs stack up to previous years

Offshore Drilling Under Fire

Oil rigs off the coast of California. (Photo: Anita Ritenour, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: New York City is the latest municipality to sue fossil fuel companies, seeking billions of dollars to address the rising seas and extreme weather that scientists link to global warming. But the Trump administration embraces fossil fuels, and when asked about the Paris Climate Agreement at a press conference with the Prime Minister of Norway on Jan 10th, Mr. Trump said the US is still out, claiming that it is important to support the present energy business.

Government leasing is key to the oil economy, and on Jan 4th, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke moved to open up nearly all of the outer continental shelf for drilling. But now suddenly the waters off the coast of Florida are exempt, after Secretary Zinke spoke with offshore drilling opponent and Florida Republican Governor Rick Scott. Other governors, equally unhappy about potential drilling near their coasts, are now banging on the door as well, which is no surprise to Steve Kretzmann, the Founder and Executive Director of Oil Change International. Steve joins us now, welcome back to Living on Earth!

KRETZMANN: Thanks so much, Steve. Great to be here.

CURWOOD: So, Steve, who is speaking out against the plan and why are we seeing such bipartisan opposition to offshore drilling here?

KRETZMANN: Well, we're seeing the bipartisan opposition because people who actually live in these coastal communities understand that the oil industry is a threat to their way of life and to their economy as it's currently constructed, and you know, even Rick Scott and other Republicans understand that this is a problem and they are not going to benefit from an increased oil industry presence off of their coast.

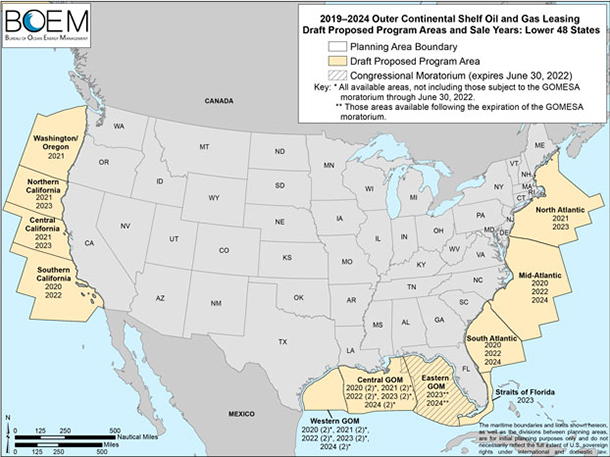

In its draft proposal of the 2019-2024 Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing Program, the Department of the Interior offered up virtually all of the outer continental shelf surrounding the lower 48 states for potential lease sales. (Photo: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management)

CURWOOD: Yeah, I gather – what the governors of New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Oregon, Washington state, California, of course, are saying ‘no.’ We've had a partisan divide on many issues in this country, but I guess not on this matter drilling offshore. What's at risk of drilling offshore that so many of those folks are willing to stand up and say ‘no.’

KRETZMANN: Well, there's the ever-present risk of a spill and for anyone who has lived in close proximity to oil industry operations, it's a question of when, not if, a spill will happen, but there's also all the other things associated with oil industry operations which generally do not tend to help local coastal growth. In particular, they tend undermine it, be cyclical employees, employees coming in from out of state and in some cases out of country, and it's just not a really good basis for job growth and for economic growth for those areas which are not already deeply deeply indebted to the fossil fuel industry.

The Department of the Interior proposed 19 potential lease sales for offshore drilling in the waters off Alaska. (Photo: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management)

CURWOOD: So, what do you make of the fact that Florida is the only coastal state with these proposed leases that is being exempted at this point?

KRETZMANN: Well, it's funny because when I first heard this, before the exemption happened, I thought, ‘Well, that's interesting, Zinke and Trump just gave Florida to the Democrats in the 2020 election and 2018 midterms,’ and apparently Rick Scott and some others had the same thought because they quickly reversed it. I think it's – having worked in Florida on offshore drilling, I can tell you it is very much across-the-spectrum, uniting issue that nobody wants rigs off those coasts, and so I think it's not surprising to me that there was that pushback quickly. I think it's surprising frankly how quickly it happened, the fact that Zinke announced it in a tweet apparently without even consulting with his own bureau of ocean energy management, and industry is apparently upset today that they weren't consulted on this either.

The Trump administration proposes to loosen regulations on blowout preventers put in place after the Deepwater Horizon disaster of 2010, which killed 11 people and spilled more oil than any other oil spill. (Photo: US Coast Guard, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

It certainly also opens up a question of legality around the rest of the program overall. I mean it's pretty obviously a political decision to exempt Florida, so then, on what grounds are you choosing to exempt or not exempt the other coastal areas?

CURWOOD: What concerns you the most about this plan to open up so much of the US continental shelf to oil drilling?

Earth’s “carbon budget” is dwindling, says Steve Kretzmann: The oil and gas reserves that are already in production have more than enough carbon to push the world past the goals set forth in the Paris Climate Accord in 2015. Above, melt ponds in the Arctic paint a picture of a warming world. (Photo: NASA/Kathryn Hansen, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

KRETZMANN: I mean, I think it's just another manifestation of the fact that this administration and this Republican controlled congress are really, literally pulling out all the stops on the fossil fuel industry. They're willing to offer everything that they can possibly offer to them. There's not a new oil subsidy they don't love, and there's not a regulation or community protection they don't hate, and you know offering up all of our coasts for the possible pollution and profit by the fossil fuel industry, by the oil industry is only the latest bit of that.

CURWOOD: And what concerns do you have about the climate connection to these leases?

KRETZMANN: So, from a climate perspective, as we have seen the World Bank acknowledge, as we have seen France acknowledge, as we saw this week in New York begin to acknowledge the expansion of the fossil fuel industry is completely out of step with where we need to be, and so we have enough carbon already in currently operating wells and mines around the world to blow past our Paris goals, to go beyond the two degree limit which is what we have internationally agreed. Now, obviously that doesn't matter to the Trump administration, but to the rest of the world it really does, and so we're seeing a big shift where the bar for climate leadership is really being raised and the newest most inspiring climate leaders are those who are going to stand up and say "no" to the fossil fuel industry and recognize there's an inevitable decline that has to happen here, an inevitable decline that we have to go through on production.

Steve Kretzmann is the Founder and Executive Director of Oil Change International. (Photo: Oil Change International)

It doesn't mean, you know, the industry likes to characterize this as, oh my God you know everyone will freeze in the dark in our cars won't start tomorrow. No one's talking about turning off gas pumps or energy tomorrow. What we are talking about is recognizing that the climate science says in 30 years we've got to be done with this stuff. We've got to be essentially at zero and so we need to manage that decline, and expanding the axis of the industry is completely the wrong direction to go.

CURWOOD: By the way, Steve. Congress recently allowed a tax on oil companies to expire at the end of 2017. It was a nine cents per barrel tax that funded the oil spill liability trust fund to the tune of a half a billion dollars a year, basically there to pay for oil spills. How important was that tax and why do you think that it went away?

KRETZMANN: I think that tax was important because it's important that the people that are profiting from this pollution pay into the fund that's going to be used to clean it up. That said, that fund itself already had some unfortunate restrictions on it. Tar sands producers did not need to pay into it, and it was capped off at about a billion dollars per incident, which in a big oil spill goes pretty quick, actually. And so what this is an attempt to actually get the payments upfront from companies for the fact that inevitably we know that they're going to spill. Instead by limiting that tax, by ending that tax they're shifting the burden of the payment for those cleanup costs back to taxpayers.

CURWOOD: Steve Kretzmann is Executive Director and Founder of Oil Change International. Steve thanks for taking the time with us today.

KRETZMANN: Thank you, Steve. Always a pleasure to be here.

Related links:

- VOX”Florida got an exemption to the offshore drilling plan. Now 12 other states want one too”

- The Daily Beast: “Trump’s Offshore Drilling Plan Will Spark an Environmental Crisis”

- Forbes: “Why Trump’s Offshore Drilling Expansion Won’t Be So ‘Yuge’”

- Interior Department press release on the offshore drilling plan

- About Steve Kretzmann

[MUSIC: Celso Fonseca, “Por acaso pela tarde,” on The Now Sound Of Brazil 2, Ziriguiboom]

CURWOOD: Coming up, how virtual money can have a real energy cost. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth, keep listening!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: MEDESKI, MARTIN & WOOD “NORTH LONDON”, JUICE Indirecto Records]

Nature, The First Best Teacher

The students work on their motor skills by climbing up and over a fallen tree in the woods. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. If you ever wondered why America is slow to protect the environment compared to Europe, you might consider how we educate our children. Play is the serious business of childhood, as Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget famously declared, and at about the age of three, kids begin noticing how their play interacts with the environment around them. Starting preschool at three is a predictor of success as an adult, and some say a predictor of lifetime environmental awareness if it includes plenty of structured play outside, an approach more popular in Europe. But it also has believers here in the US, and Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb takes us now to a nature preschool in wintry New Hampshire.

[SOUNDS OF WALKING ON ROCK]

BASCOMB: Parents gripping cups of hot tea and coffee drop their kids off at pre-school on a cold sunny morning in Chester, New Hampshire.

The kids seem to love exploring and playing in the woods. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

WOMAN: Bye, honey. Have a good day!

BASCOMB: The toddlers, wearing brightly colored snow suits and wooly hats, waddle towards a big log next to a pile of sand. A few pots and pans and lots of imagination make that fallen tree a kitchen and the sand pretend food.

GIRL: The restaurant is open! Benjamin, the restaurant!

[SOUNDS OF CLATTERING POTS AND PANS, BANGING, KIDS CHATTER]

BASCOMB: The kids run around, dig in the sand, and play kitchen until their teacher, Sarah Drowne Surrette, lets them know it’s time to get started with school.

[TEACHER AND CHILDREN IMITATE OWL CALLS]

BASCOMB: Sarah’s kindergarten group are the Great Horned Owls. She hoots to get their attention and they respond.

[OWL CALLS FROM KIDS]

SARAH: Does everybody have their snow gear on?

KIDS: Yeah!

SARAH: Mittens?

KIDS: Yeah!

SARAH: Hats?

KIDS: Yeah

SARAH: Alright, we’re ready.

BASCOMB: Ready to head out into the eight acres of forest and field that are the Chesterbrook School of Natural Learning.

[SOUNDS OF WALKING AND SHOUTING]

BASCOMB: Sarah taught first grade in a traditional public school for 13 years but for her oldest daughter, Olive, she wanted a different experience. So she started a nature-based preschool for her toddler and one other child. Two years later she has 36 students enrolled in three different classes and a long waiting list.

Sarah and her students sit for their morning meeting at a sunny spot in a field. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

[SOUNDS OF CHILDREN]

Sarah and her seven kindergarteners hike to a sunny spot in a field for their morning meeting. The kids take off their backpacks, sit in a circle and listen to Sarah.

SARAH: This morning I looked up and right over there into the field I saw two giant creatures that had four legs, they were brown, and they were running.

BASCOMB: She puts her thumbs to her temples and spreads her fingers wide.

SARAH: And one of the creatures had these big things on top of its head. Do you want to take a guess at what they were?

KIDS: Deer!

SARAH: Deer! Now, I saw two of them. One of them had antlers on top and one didn’t so what’s the one with antlers on top of its head called?

KIDS: Dad. Buck!

SARAH: Buck, it’s the dad. That’s right and the other one didn’t. Do you remember?

KID: Doe!

SARAH: Doe, yeah!

BASCOMB: Then Sarah helps the kids read a message she wrote on a white board about what they’ll be doing today.

KIDS AND SARAH: Good morning, today is Tues….

SARAH: Oh, you were doing what good readers do. You looked at that beginning letter. She saw a T, she thought it was Tuesday. We have another day of the week that starts with a Th and Th makes this sound thhh…

KIDS: Thursday.

SARAH: Thursday! Today is Thursday, good job observing those letters.

BASCOMB: After reading together, there’s a short math lesson and discussion about the difference between wild and tame animals.

SARAH Alright, my friends I think we we’re sitting long enough. Why don’t we hike out to the forest, okay?

[SOUNDS OF CHILDREN YELLING, AND RUNNING]

BASCOMB: The kids run towards the forest and tell me the best way to go.

BOY: So follow us, don’t go under the big tree!

BASCOMB: Down a path in the woods at a clearing, there’s a huge fallen tree. They take turns crawling up and over it.

SARAH: This is where they’ll work a lot on their gross motor, you’ll see them with cooperative learning.

GIRL: Hey mason, do you want to do the log with us? Do you want to do the straight log with us, Mason?

BOY: Hey, watch me!

BASCOMB: These children are outside snow, rain or shine, every day through the long, New England winter unless it’s so windy that falling branches and debris are a concern. They dress in warm layers, but five year old Phoebe says there’s another way they stay warm.

Five-year-old Phoebe dresses warmly, but says the best way stay warm is to keep moving. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

PHOEBE: We climb trees and climb stuff and we walk around to get our bodies warmer.

BASCOMB: Further on they stop at a frozen puddle to slide around on the ice.

GIRL: When there’s really hard ice we like to skate on it!

BASCOMB: Sarah says they collected chunks of ice like this to build with. In fall they harvested grapes to make jelly and in early spring they’ll learn how to make maple syrup.

[CHILDREN WALKING]

BASCOMB: After a couple of hours it’s time to hike back to the classroom for a snack the kids prepare for themselves, followed by more math and letter flash cards. Then lunch, meditation and yoga. Finally, back out to the forest for the afternoon before parents come to pick them up.

[KID SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Erin Terry is mom to three year old Olivia. She says at first she was hesitant about her daughter being outside every day.

TERRY: Because I thought inside is safer. There’s ticks outside, it could be dangerous in the forest, they could get lost. Things like that. And then once she started coming here I just noticed how much she was growing educationally and socially.

BASCOMB: Kristen McGrew has two kids enrolled here – she was a public elementary school teacher for 15 years.

MCGREW: Personally, I wish that every student that I’ve ever had or will come across would have an opportunity like this. It’s not something that every child is able to have, especially in the inner city schools that I was teaching in.

BASCOMB: Nature-based preschools have been popular in Europe for decades, especially in Germany and Scandinavia. They are a relatively new idea in the US but are becoming more common – a recent survey found there are more than 250 nature-based preschools across the US, two-thirds more than last year. Advocate Richard Louv says that growth is good news for kids.

The kindergarteners slide around on the ice and work together on problem solving. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

LOUV: There is a new body of evidence out there that really shows a connection at least between spending more time in nature and being healthier, happier, and maybe even smarter.

BASCOMB: Richard Louv has written nine books about children and nature and co-founded the Children and Nature Network. In his book Last Child in the Woods, Louv coined the term ‘nature deficit disorder’. It’s not an actual medical diagnosis, but he points out that the last decade or two in which children spend less time outside coincides with a rise in childhood obesity. Louv says simply sitting in a classroom all day can be a problem for kids.

LOUV: Just about everybody knows that sitting is the new smoking. It produces many of the same diseases or symptoms as cigarettes. And so, many people have standing desks and all of that and yet our children are still sitting in the schoolroom aren’t they? And we’re cutting recess, and this goes against decades of research that show physical activity stimulates cognitive functioning. It improves physical health. It makes better students, and yet we’re ignoring that research.

BASCOMB: Louv worries that kids learn about weather events like hurricanes and climate change in school and can see nature as threatening instead of welcoming. He says it’s important for kids to develop a personal relationship with nature while they’re young.

LOUV: It’s very hard to protect something if you don’t learn to love it. It’s impossible to learn to love it if you’ve never experienced it.

BASCOMB: It’s that personal relationship that Sarah’s students at the nature school are working on and … singing about.

SARAH AND KIDS (singing) It’s a great day to be alive. I know the sun still shines when I close my eyes. There’s fun times in the neighborhood and why can’t every day be just this good.

Sarah and her students work with letter flash cards in the classroom. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Of course, preschools like this aren’t necessarily an option for most kids but there are things parents can do with their children to foster a love of nature ... Read a book outside. Turn over rocks and see what’s living there. Richard Louv suggests a belly hike – get down on your belly in the backyard and have a close look at all that lives between the blades of grass … all things to give children a sense of the diversity of the world and their place in it.

SARAH (singing) Hello world!

KIDS: Hello world!

SARAH: My old friend

KIDS: My old friend!

BASCOMB: For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb in Chester, New Hampshire.

SARAH: It’s another day!

KIDS: It’s another day!

SARAH: I’m glad to see you again.

KIDS: I’m glad to see you again.

[SINGING FADES AWAY]

Related links:

- Chesterbrook School of Natural Learning

- Children and Nature Network

- Richard Louv

Bitcoin, The Energy Hog

Bitcoin is today’s world’s most commonly-traded cryptocurrency. Over the course of 2017, the value of a single Bitcoin increased from around $1,000 in January to over $18,000 in December. On January 10, 2018, the value is now just over $13,000. (Photo: Christoph Scholz, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Bitcoin, the most popular of the new digital currencies, has shot up in value, and even though you can’t hold one in your hand, bitcoins require massive amounts of energy, and here’s why. Every transaction related to them is verified by a key group of users, called miners, who collect all those records into groups known as blocks, and compete to get their block added to the chain of record.

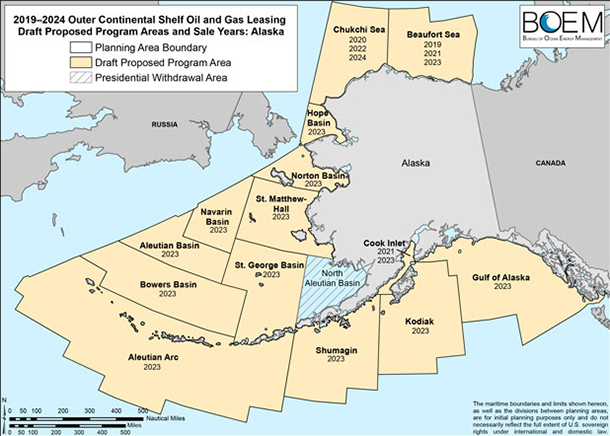

Every 10 minutes or so, one block is randomly selected, winning that miner a prize of new Bitcoins, and the rest are discarded. Data consultant Alex de Vries calculated Bitcoin’s energy costs, and according to his Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index, submitting all those numbers demands so much computing power that Bitcoin consumes more electricity than 159 individual countries. But Alex de Vries says the high carbon cost is intentional.

DEVRIES: Well, the energy costs are part of the reason why Bitcoin is so secure, because if you want to attack the system, first of all you need the machines and you have to spend a huge amount of money to pay for all the electricity to simply take control over the network. So, in essence, it's really part of what makes Bitcoin secure.

According to the Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index that Alex de Vries developed, Bitcoin’s overall energy cost has increased relatively steadily over the past month. (Photo: Alex de Vries)

CURWOOD: By the way, how many, if any, do you have and if you do have them when did you buy them?

DEVRIES: [LAUGHS] Well, I should have bought a lot, though I actually had some bitcoins back in the day, but I already sold them in 2015, so I'm no Bitcoin millionaire. I do know that at some point I learned about the energy consumption because before 2015, I didn't know it was consuming such a huge amount of electricity because as a user you're never confronted with these costs. The electricity bill ends up at the miners’, so you'll never see how much energy is being consumed by the system.

CURWOOD: What about the creation of these Bitcoins? How much energy does it take to create one bitcoin?

DEVRIES: Well, something like fifty thousand kilowatt hours per mined Bitcoin.

The Tianjin Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle Power Plant Project in Northeastern China. Coal is a critical energy source in the country and Bitcoin mining is known to capitalize its cheap power. (Photo: Asian Development Bank, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Fifty thousand kilowatt hours. And how much does a kilowatt hour of electricity cost?

DEVRIES: It depends on where you are. In the US, the average residential rate is probably 10 to 12 cents per kilowatt hour. If you're in China, it's a lot cheaper. Then, you're probably paying just four to five cents per kilowatt hour, and in total the whole network is paying an amount of almost $2 billion US dollars per year just to mine Bitcoins.

CURWOOD: So, where in the world are Bitcoins most commonly mined these days and what kind of energy sources do these mining operations typically employ?

DEVRIES: So, what we see is that most of the miners are actually located in China, which makes the energy consumption problem a whole lot worse because China doesn't have a very clean electricity grid. From several miners, we know that they are located very near to coal-based power plants, so they are drawing a lot of coal-based electricity. That causes the carbon footprint of each Bitcoin transaction to be gigantic as well.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it there's a limit to Bitcoins, that there will only ever be some, what, 21 million in circulation, and at that point I would imagine that might not consume as much energy as they do now or maybe I'm wrong there.

Bitcoin mining demands massive amounts of computational power. Most mining operations are comprised of networks of highly efficient computers working in tandem. (Photo: Nathan 11466, CryptoCurrency 360, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DEVRIES: Well, you're indeed right there will never be more than 21 million Bitcoins. They're released slowly over time as a reward to those who are mining Bitcoin. Bitcoin once started with a block reward of 50 Bitcoins, meaning that every one who created a new block for the block chain would get 50 Bitcoins. Nowadays, that is just 12 and a half Bitcoins per block, so it has already halved two times and it will keep on halving every four years and in a few decades all Bitcoins will be mined and there will be no more block reward. Now, you could say that might lower the energy cost simply because if the reward goes down so will the amount miners are spending on electricity, but that's a bit too simple unfortunately because as a user you're also paying transaction fees. And the whole idea is that those transaction fees, which are also claimed by the miners, will end up supporting the Bitcoin infrastructure.

CURWOOD: Because this system requires a lot of computer power and computer sophistication, it would seem to be adding to the financial fortunes of the elite as opposed to the general population of our planet. Your view?

DEVRIES: So, the strange thing is that even though we do end up with that result, it's not because of the energy cost because the energy costs, they aren't paid by the user, so that's not a problem. The only problem is that as a user you are paying for something, you are paying for getting priority in getting processed by the Bitcoin network. The whole network can effectively process only three to four transactions every second, so that's a very very small amount and if you want to be processed in a reasonable amount of time, you're going to have to pay a certain fee.

Alex de Vries is a data consultant and the founder of Digiconomist.net. (Photo: Alex de Vries)

In December, we actually saw that the average fee paid by people to simply get priority in being processed was around 26 dollars per transaction. So try to imagine if you are paying for a cup of coffee and you have to pay at least 26 dollars in transaction cost simply to have your transaction processed, that's definitely not something that you're going to be able to afford if you are poor. So, in that way it's actually going to contribute to raising economic inequality over time, or at least that's something that might happen.

CURWOOD: Look ahead at the future cryptocurrencies. To what extent are these going to replace government issued currencies ... the Dollar, the Pound, the Euro becomes irrelevant?

DEVRIES: Oh boy, you know, I don't know. I don't think it will replace the dollar. I do think that there will always be a niche for Bitcoin. You always have countries that are facing hyperinflation monetary systems that are collapsing. Places like that are actually pretty nice places to start a virtual currency. Now, if we're talking about the US, do we distrust our financial institutions that much that we desperately want to get away from them and all dump our money in Bitcoins? Well, you know, I have no problem with my bank. I trust my bank. I'm fine with them doing my financial transactions, so I don't really need Bitcoin.

CURWOOD: Alex de Vries is a data consultant and founder of digiconomist.net. Thanks so much, Alex, thanks for taking the time.

DEVRIES: And thank you very much.

Related links:

- Digiconomist Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index

- Vox: “Bitcoin’s price spike is driving an extraordinary surge in energy use”

- Ars Technica: “Bitcoin’s insane energy consumption, explained”

[Pink Floyd “Money”, The Dark Side of the Moon, Sony (Remastered) 1973]

CURWOOD: Coming up An 80 year-old success story faces new threats. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth, stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies – combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning in to the Race to 9 Billion podcast, hosted by UTC’s Chief Sustainability Officer. Listen at raceto9billion.com. That’s raceto9billion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: From the 2006, Charlie Hunter Trio's album Copperopolis. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pkD50H06UYE]

Beyond the Headlines

Coal stockpile. (Photo: Bob Burton, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. We’ll check out what nuggets Peter Dykstra has mined beyond the headlines now. Peter’s an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN dot org and DailyClimatedotorg, and he joins us from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey Peter, has the weather warmed up for you?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, starting to warm up a little bit, but the idea of what a cold winter is here in the South is a little bit different than what a cold winter is up where you are in New England.

CURWOOD: Oh yeah. So, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is a fairly obscure agency whose five commissioners – four of whom were appointed by President Trump – rule on how billions of dollars can change hands between the federal government and the energy industry.

So you might think that an Energy Department proposal to keep aging coal and nuclear plants open – ostensibly to keep the biggest variety of power sources available – and to make the supply more reliable – would sail through. But that isn’t what happened – the commissioners turned it down.

CURWOOD: Huh, sounds like they wanted to let the market decide, and not pick winners and losers in energy.

DYKSTRA: Right. The DOE proposal would have prevented the closure of coal and nuke plants, which generally cost more to run than natural gas plants. Wind farms and power from the sun are on the brink of leaving coal or nukes in the competitive dust. Studies suggest that backing more expensive power like coal and nuclear could cost ratepayers nearly $12 billion dollars nationwide.

CURWOOD: So a commission dominated by Trump appointees just sent a sharp rebuke back to Energy Secretary Rick Perry, huh?

A red fox in the Izembek National Wildlife Refuge, where the Interior Department plans to allow the construction of a controversial road between the Alaskan towns of King Cove and Cold Bay. (Photo: Kristine Sowl / USFWS, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Yes, and they also had a strange bedfellows coalition of Big Oil and Gas, environmentalists, conservatives, that sided with the Commissioners. Had they approved the DOE proposal, electric grid operators would have been required to charge a tariff to most major forms of energy production, but not coal or nukes.

CURWOOD: So it is proving harder to bring back coal than Mr. Trump promised. Hey, what’s next?

DYKSTRA: Let’s move on to a story from Alaska.

CURWOOD: You’re talking about the renewed effort to drill in the Arctic Ocean or ANWR?

DYKSTRA: No, this one’s from the Alaska Peninsula, that stretch of land between the Alaska mainland and the Aleutian Islands. King Cove is a town of less than a thousand people. For years, they’ve lobbied for approval to build a one-lane, 12-mile gravel road to connect the town to a regional airport at the town of Cold Bay. King Cove’s tiny airstrip can’t accommodate emergency flights to hospitals.

CURWOOD: Well that all seems to make sense, a short, one-lane gravel road would seem like it wouldn’t break the bank, so I guess there’s gotta be a catch, huh?

DYKSTRA: There is: The road would pass through a national wildlife refuge wilderness area, potentially disrupting feeding and other activities for waterfowl, seabirds, bears, caribou and more. And even though they offered a land swap for the wilderness area, the road would be built on, the battle lines are set: conservationists against Federal and state officials.

CURWOOD: And of course, roads are the kiss of death for real wilderness. Finally, let’s get another sample of environmental history, Peter – what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Let’s travel down the twisting path of what local residents and public safety officials know about the toxic chemicals in their midst.

CURWOOD: Uh, toxic chemicals are among our favorite topics, so go ahead.

DYKSTRA: In 1986, Congress and President Reagan included Right-to-Know provisions in a bill re-authorizing Superfund, the not-so-successful effort to clean up toxic sites. The measure also set up the Toxics Release Inventory, or TRI, which is still in use today.

CURWOOD: Despite the conspicuous changes at the EPA over the past year, I might say.

DYKSTRA: That’s right. But for the most part, industry hated disclosure laws, arguing that if they told local activists and fire departments about the stuff they had on site, it could fall into the hands of terrorists.

In the 1990s, public efforts to push for greater disclosure laws continued. And then in 2001, two things happened: A CSX freight train derailed in a century-old tunnel beneath Baltimore, evacuating much of the downtown. And firefighters didn’t really know what they were fighting.

Fighting a blaze becomes particularly dangerous for firefighters when toxic or explosive chemicals could be involved. (Photo: LadyDragonflyCC, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And this of course was a train passing through hundreds of at-risk communities.

DYKSTRA: Right, and of course the other thing that happened in 2001 was 9/11, which gave industry a much wider license to not disclose what chemicals they had on site. In Texas, where the state agency was not too keen on enforcing EPA edicts, a 2013 fire broke out at a fertilizer plant in the town of West. Firefighters unknowingly walked straight into an explosion. Fifteen people died. And last year, uncertainty about what the Arkema chemical plant had on site led to mass evacuations during the floods brought on by Hurricane Harvey.

CURWOOD: So what you don’t know CAN hurt you. Peter Dykstra is with Daily Climate dot org and Environmental Health News, that’s EHN dot org. Thanks a lot Peter, talk to you soon!

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks – we’ll talk to you next time.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on all these stories at LOE dot org

Related links:

- The Washington Post: “Trump-appointed regulators reject plan to rescue coal and nuclear plants”

- The New York Times: “In Alaska, a Deal Is Made for a Controversial Road Inside a Refuge”

- EPA: About the Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) Program

- The Baltimore Sun: “Train fire, toxic cargo shut city”

- The Texas Observer: “Your Right Not to Know About that Exploding Chemical Plant Near Houston”

[MUSIC: Dust Bowl Soundtrack

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pVZrMBb4grc]

Saving Trees That Helped Save Dust Bowl America

A shelterbelt in Burt County, Nebraska, photographed in 1937. The simple aesthetic of a stand of trees in an otherwise totally flat landscape had a powerful sentimental as well as ecological impact, says Vaughan. (Photo: The Forest History Society, Durham, NC)

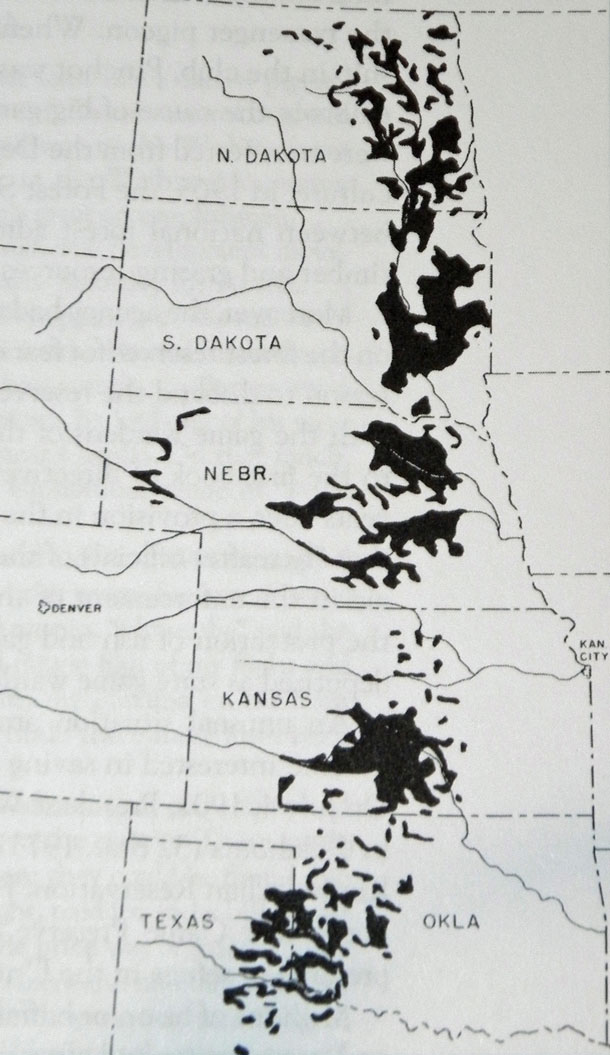

CURWOOD: The Dust Bowl was a great American disaster. As they moved west in the 19th century, settlers ploughed under the seemingly endless prairie to produce grain. At first it went well, but by the 1930’s the rains failed, and the wind tore away the topsoil by the ton, sending it flying across the Great Plains, choking livestock and homes and people, and driving them off the land.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had an answer. He mobilized the US Forest Service, the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration to create shelterbelts by planting millions of trees to hold down the earth. Decades later many of those trees still stand as a vital green protective strip, but the shelter belts face a new threat from farmers eager to maximize their annual harvests. Carson Vaughan wrote about the shelterbelts for the Food and Environment Reporting Network, and joins us now from Omaha Nebraska – welcome to Living on Earth!

VAUGHAN: Happy to be here.

CURWOOD: So, Carson, you're in Nebraska now. If you could go back in time, say 80 years, what would the Dust Bowl have looked and felt like there?

VAUGHAN: Yeah, we're talking heavy winds, one year after another of very intense drought and that just got emotionally, and certainly physically draining, for farmers and ranchers out in the Great Plains. I researched one specific farmer in Nebraska who farmed near a now kind of ghost town called Inavale and each year it got a little bit worse and a little bit worse and his crops went from fairly good in the late '20s to progressively worse and he kept a diary, so see you can see him undergoing physical and mental turmoil. His crops are literally blowing away right in front of him. Each year is getting hotter and drier and they're running out of water and their cattle are dying, they're choking on the dust, you know, and people were dying from this. And their cattle certainly were and their crops certainly were and they were running out of money and running out of hope.

The major planting areas of the Shelterbelt Project from 1933-1942. (Photo: U.S. Forest Service, Wikimedia Commons CC)

CURWOOD: So, how did this idea of for the wall of trees come about?

VAUGHAN: Well, it's sort of legend at this point. I couldn't track down the original source, but a lot of journalists back in the day were citing a story of FDR, then Governor Roosevelt, was campaigning in Montana and his train was delayed by a wind eroded hillside in Butte, Montana. And apparently at that time he started brainstorming and came up with this plan of, what if we had this solid wall of trees running up and down the plains that provided some sort of blockage for that dust blowing around everywhere, and so that was FDR's original plan.

He wanted literally a single wall of trees several miles wide running from the Canadian border all the way down to the Texas panhandle. Now, that was later on modified a little bit by his advisors and by the Forest Service director and that kind of thing and they turned it into forest protection strips. And so it still went from North Dakota all the way down to the Texas panhandle but it wasn't one solid wall of trees. It was a series of walls of trees all the way down.

CURWOOD: So, described this great green wall of trees. What kind of trees it made of?

VAUGHAN: All sorts of trees. The Forest Service at the time tried their best to use trees that were native to the regions they were planting them in, and when they couldn't do that they used exotics, but exotics that they had already proven to be reliable trees for a shelterbelt. So, they were using you know, pines, oaks. They kind of used cottonwoods as the PR campaign for shelterbelts. In the long run cottonwoods aren't the best. Their lifespan isn't as long but they grew very quickly in pretty poor soil and so they could point to those after planting just the year before and say look out quick these trees are growing, look how sustainable this is.

A shelterbelt on the Albert Stuhr farm in York County, Nebraska, 1947. Forest Service and Civilian Conservation Corps workers first began planting shelterbelts in the 1930s and 1940s to provide protection against Dust Bowl storms. (Photo: The Forest History Society, Durham, NC)

CURWOOD: So, how effective was it at stabilizing the land and protecting the topsoil and how effective is it still today?

VAUGHAN: It was very effective. The fact that there are still up today, at least a portion of them, I think is sort of testament to their usefulness. Certainly we're seeing them torn down more and more all the time, and that's sort of the crux of my story, but they served a huge purpose at the time. I mean, obviously to plant 220-some million trees, that's a long-term effort. So, they started planting in '35. I think the first tree was in a town called Mangum, Oklahoma, and they planted for another decade and off and on they're still planted all the decades up until now and some farmers are still planting them, but people saw a real benefit to curbing all this dust blowing everywhere. I mean, it was one of the few technologies to prevent that.

CURWOOD: Chris, this shelterbelt as you call it, it just sounds so lovely so why would anyone want to cut it down?

VAUGHAN: Yeah, I mean that's a more difficult question than I had originally thought it was going into this reporting, but there are multiple reasons, the biggest of which is as you know a lot of these environmental stories turn out to be, it's money, you know, it's the economics of it all. Farmers, they see commodity prices go high and they think, well, this shelterbelt may have done something for me at one point but they're kind of in the way of what could be more row crops for me and row crops are more profitable than these trees.

So, they rip out these trees, they plant more crops and they make more money. The flip side of that though and the irony here is that in a bad here when commodity prices are low, that's another justification to rip out the trees and keep planting more because they need to like soak up every penny they can from those crops. So, whether it's a good year or a bad year, we find farmers finding a justification to rip out these trees.

CURWOOD: So, how wise is this deforestation with climate disruption continuing, drought such a danger in much of the center of our nation?

An abandoned house decays in Northeastern New Mexico. The Dust Bowl brought drought and deadly dust storms to the West during the 1930s and forced many families to abandon their homes. (Photo: J.N. Stuart, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

VAUGHAN: Yeah, I mean I think if you talk to most agro-forestry officials out here in the Great Plains they would tell you that it's a pretty short-sighted move to be tearing out these trees right now, and that's certainly not to generalize every farmer, every rancher in the Great Plains. Certainly a lot of them have that conservation ethic and understand what those trees are for, but there's a big concern that the forecast for climate change in the Great Plains is showing a mega-drought, essentially more extreme weather events, more precipitation but in oxymoronic sense also more drought, and you have more than a couple of years of drought and all these new technologies and new ag practices that we've developed in the years since the Dust Bowl aren't going to do a whole lot for you and then all of a sudden we're back in essentially a dust bowl. And so, yeah it doesn't seem like the smartest move right now for farmers and ranchers in the ag industry in general on a macro sense to be tearing out these trees left and right.

CURWOOD: What kind of suggestions have you heard to help farmers back away from this feeling of the squeeze when it comes to protecting these trees?

VAUGHAN: To be completely honest with you, Steve, what I heard most of from farmers was just ... I don't want to say depression, but they feel like there's not a great option for them, you know, that there are benefits through the NRCS or through the natural resource districts that we have in Nebraska. You can plant CRP land and that kind of thing but the benefits of going through those programs still don't seem as great as the benefits of tearing out those trees and reaping the profits for more row crops.

CURWOOD: So, CRP, you mean the Conservation Reserve Program where they get some money for protecting the trees, but it's not as much money as they get if they plant and successfully harvest the corn or the soybeans or or whatever that they want to grow there.

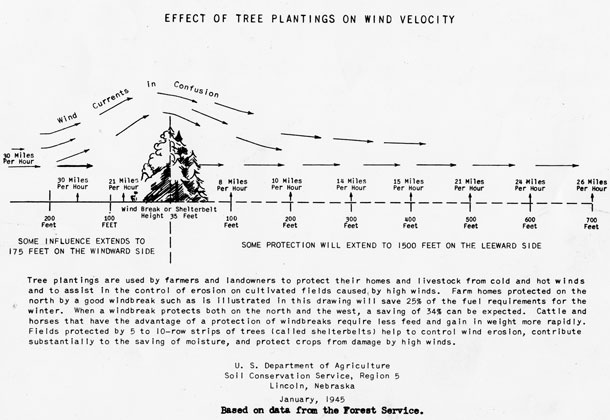

The shelterbelt design was simple: Lines of trees block the path of harsh winds, while also capturing water, providing a nutrient sink to crops, and habitat to native wildlife. (Photo: The Forest History Society, Durham, NC)

VAUGHAN: That's right. A lot farmers just don't see that payout from those cost sharing programs that they would like to, and even beyond that, you know, a lot of the agro foresters that I talked to said that you know we can show them the numbers all day long of increased yields from these shelterbelts being in place but at the end of the day, there's been so much investment in this new technology that we're using that they want to get the most out of the technology they've paid for, and so there is some sort of strange psychology going on where even when you see the numbers you're trying to justify other decisions you've already made on the farm, you've bought, you know, a giant combine that was very expensive, you've invested in center pivot irrigation and all those things you want to get your money's worth out of, and trees, unfortunately, they're just kind of forgotten about. They're left behind, they're not valued the way I think a lot of people understand they should be.

CURWOOD: So, what about irrigation? Of course, much of the plains area has the Ogallala aquifer under it. There's a lot of water but it's slowly disappearing. To what extent could irrigation be a possible solution for the region?

VAUGHAN: I would say that's where we're getting into trouble right now, Steve, and in fact, a big report came out I think the Denver Post kind of broke the story about this. They showed that the high plains aquifer was depleted twice as fast over the last six years as it was the previous 60 years. So, for people who are relying solely on using this ground water from the aquifer, I think we need to get away from that mode of thinking, and that's where all of these agroforestry officials are stepping in and saying, hey, these trees are still relevant and they're going to be more relevant the more water troubles we run into.

Pamphlets advertise the first plantings of shelterbelts in the Great Plains. Today, pressures to maximize profit have driven many farmers to cut down these once-heralded trees. (Photo: The Forest History Society, Durham, NC)

Right now, center pivot irrigation is reliant on very heavily in drought years, and it's great that we have that technology there and that we can use that when need be, but there's going to come a point when we can't always rely on that, and even if the water is still there it gets more expensive all the time. For a farmer to think that he can even afford to just irrigate his way out of a drought is really, I think, a damaging line of thought.

CURWOOD: I would imagine that the trees also affect the microclimate and add water and keep water in the soil locally. What evidence, if any, is there of that?

VAUGHAN: Yeah, I mean that's definitely true. Plenty of studies have shown that there is certainly is an effect on the microclimate, and that water retention is a big part of shelterbelts and a big part of why it helps retain the topsoil. They have their roots, they soak up the water, they provide sort of a nutrient sink for a lot of this farmland. They also provide shelter for wildlife, for birds, the birds help cut down on the insects. I mean there's all sorts of secondary benefits that these shelterbelts provide that you don't necessarily think about when you're a farmer just looking at the bottom dollar.

A 10-row shelterbelt planted in 1940 on the Dorothy A. Jones farm in Seward County, Nebraska. (Photo: The Forest History Society, Durham, NC)

CURWOOD: So how do locals feel about these shelterbelts, in particular, any sentimental attachments that would be appropriate to talk about?

VAUGHAN: There's a sentimental attachment by some farmers certainly, but there's also a sentimental attachment just by people who live out here in the plains who might not necessarily be running a farm or ranch. You know, I think of my own parents. I grew up in a small town in central Nebraska and the way I learned about shelterbelts, the way I even knew that term is because my parents would see another shelter belt coming down, and they would sort of bemoan, ‘Oh man I grew up with that shelterbelt,’ or ‘I've seen those trees all my life’ and they couldn't understand why farmers were ripping them out. And so, yes, certainly people have a sentimental attachment to it even when FDR was putting them in, the Forest Service director said don't underestimate the value of just the aesthetics of all these trees being out in what was once called The Great American Desert.

Carson Vaughan is a freelance journalist based in Lincoln, Nebraska. He partnered with the Weather Channel and the Food and Environment Reporting Network for his story. (Photo: Carson Vaughan)

CURWOOD: Carson, I got to say that the story feels ominously cyclical that things could be coming back to what happened on the scale of 80, 90, 100 years ago. How optimistic are you for the future of the Great Plains and the agriculture there?

VAUGHAN: Well, I certainly don't want to be alarmist in any way, and talking to a lot of these foresters, half would use the term "another dust bowl" and the other half would kind of shy away from that, but the half that shied away from it would still be saying, “We're going to see some pretty serious consequences”, and so I'm not optimistic that our farming practices are as progressive as they should be, and I don't think we're moving at a pace that we should be, but again that's not to say that there aren't plenty of farmers and ranchers out there who understand the benefits of this and are replanting their shelter belts. I am most concerned about the farmers that are tearing them out for a quick profit and forgetting to replant those trees.

CURWOOD: Carson Vaughan's a freelance journalist based in Lincoln, Nebraska, who partnered with The Weather Channel and the Food and Environment Reporting Network for the story. Carson, thank you so much for your time.

VAUGHAN: Thanks so much, Steve.

Related links:

- The Weather Channel: “Uprooting FDR’s “Great Wall of Trees”

- The Forest History Society

- Shelterbelt Design blog: The Story of the Great Plains Shelterbelt Project

[MUSIC: Donald Fagen “Walk Between the Raindrops”, The Nightfly, Warner Bros. 1982]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth