July 31, 2009

Air Date: July 31, 2009

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Clouds Shadow Warming Predictions

View the page for this story

A new study finds that some clouds could make our warming world even warmer. But scientists have had a difficult time understanding the nebulous nature of clouds, and only one climate change model has been able to reproduce the results of the recent findings. Lead author Amy Clement talks with host Jeff Young about what clouds could mean for our end-of the-century forecast. (06:20)

Entering the Plastic Vortex

View the page for this story

A pair of research vessels is set to sail to a region of the Pacific Ocean known as the Plastic Vortex, an area of plastic twice the size of Texas that weighs nearly 4 million tons. All of this plastic is killing marine life and toxic chemicals from the plastic waste have the potential to accumulate in the food chain and effect human health. Researchers plan to study and document this plastic soup, as well as test methods for removing the debris and reprocessing it into diesel fuel. Host, Jeff Young, speaks to Mary Crowley and Doug Woodring, founders of this mission called Project Kaisei. (06:30)

Cheyenne May Yield to Coal

/ Daniel KrakerView the page for this story

The Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in eastern Montana lies on a blanket of rich coal. But tribal members have never wanted to mine it, even as mining surrounded them. As Daniel Kraker of Arizona Public Radio reports, that may be changing. (10:00)

The Diné Way

View the page for this story

The Navajo are looking for alternatives to the fossil-fuel based economy that has dominated its reservation for decades, and left it with a 50 percent unemployment rate. Thee Navajo Nation Council recently voted in support of green jobs, legislation Wahleah Johns worked to promote. She's co-director of the non-profit Black Mesa Water Coalition, and she talks with host Jeff Young about the past and future of her nation. (06:00)

Listener Letters

View the page for this story

Corrections, compliments and complaints. . .our listeners sound off. (02:00)

Eco-Islam

View the page for this story

Green is the color of the conservation movement, and the traditional color of Islam. At a recent conference in Istanbul, Islamic scholars from all over the Muslim world gathered under an especially green banner to talk about climate change. Mahmoud Akef (MAHMOOD AKEEF) organized the conference, and talks with Jeff Young about the seven year Muslim Action Plan on global warming, which sets out to green the Hajj, boost awareness, and create an eco-Islamic label for products. (05:30)

Hydrogen Feathers

View the page for this story

Heated chicken feathers can efficiently store hydrogen without a huge price tag, say chemical engineers at the University of Delaware. Annie Glausser reports. (01:30)

Python Be Gone

View the page for this story

The Florida Everglades might be known for alligators and crocodiles, but there’s another reptile snaking through those wetlands: the Burmese python. The Burmese python has become well established in the Everglades, even though it doesn’t belong there. Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar recently announced plans to advance a python eradication program. He’s calling on licensed volunteers to hunt down and remove the estimated 100,000 pythons from the Everglades. Host Jeff Young talks with volunteer python hunter Greg Graziani. (06:30)

Green Brown Lawn

/ Pat PriestView the page for this story

Writer Pat Priest of Athens, Georgia isn't interested in keeping up with the Joneses. In fact, while her neighbor is busy tending to his sodded lawn, Priest has been undoing her grass, and putting down layers of recycled paper and mulch. (03:05)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Jeff Young

Guests: Mahmoud Akef, Amy Clement, Mary Crowley, Greg Graziani, Wahleah Johns, Doug Woodring

Reporters: Daniel Kraker

Commentator: Pat Priest

Note: Annie Glausser

[THEME]

YOUNG: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

YOUNG: I’m Jeff Young.

What watching the clouds can tell us about climate change. Scientists see evidence of a vicious cycle as warming thins the ocean’s clouds, letting in more sunlight.

CLEMENT: Sets off a chain of events that actually feeds back on itself so warming produces cloud cover change which produces more warming which produces more cloud cover change.

YOUNG: How that kind of feedback loop could lead to an even warmer planet.

Also – the changing energy future for Indian country. The Cheyenne fought for years to keep their land free from mining – but now they reconsider coal.

LIMPY: The revenue that would come from that coal will address our needs for money for education, housing for all our people.

YOUNG: And lawn care made easy—by giving up on the grass.

Those stories and more - this week on Living on Earth! So stick around.

YOUNG: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young.

Clouds Shadow Warming Predictions

(Photo: Shadiac )

Ralph Waldo Emerson once compared nature to “a mutable cloud, always and never the same.”

Climate scientists trying to understand how nature is changing with global warming find clouds a crucial and frustrating part of the picture. Could clouds get thicker and perhaps offset warming? Or shrink and add to the warming cycle?

A new study on clouds published in the journal, Science, clears things up a bit. And the findings have big implications for just how hot the planet might get. Amy Clement is a co-author. She’s a professor of meteorology and physical oceanography at the University of Miami.

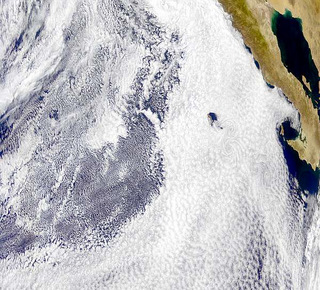

Professor Clement started with decades of data about low-lying clouds over a part of the Pacific.

Amy Clement.

YOUNG: So they’re reflecting some sunlight back up towards space, but they’re not acting like a blanket like some clouds do.

CLEMENT: That’s exactly right, yes.

YOUNG: How do you go about studying clouds? I mean they’re pretty ephemeral things.

CLEMENT: There are two ways of looking at clouds: from below and from above. Sailors have been making measurements of clouds looking up at the sky, determining what fraction of the sky is clouded and writing those down and reporting them back to a centralized archive. And then another way to look at clouds is from satellites. So satellites send down information from the atmosphere in the form of numbers basically, and those numbers are converted into a cloud faction that can then be compared with what a surface observer sees.

Clouds from above: low-level clouds cover the Pacific off the coast of Baja California, helping cool the climate. (Courtesy of NASA)

CLEMENT: They correlated actually shockingly well. And what we found was that when the surface of the ocean is warm, there is less cloud cover. And we also included in our analysis information about the sunlight that’s being reflected. And what we find is that when the cloud cover is reduced, it lets more sunlight in to the surface and that change is actually largely responsible for the surface warming.

YOUNG: Now a few scientists theorize that clouds might work the other direction – it’s gonna make things cooler. What does your report say about that?

CLEMENT: Well, it’s always possible that they might be right, but the onus is on them to show that there’s an observational support for that happening. Right now the only observational support we have is that as the surface warms, this low cloud cover decreases. And until someone can show the opposite, then we don’t really have any reason to reject that hypothesis.

YOUNG: So what’s going on here with the ocean getting warmer, the cloud cover getting thinner, more sunlight getting down to the ocean and it getting even warmer – it’s kind of a vicious cycle.

CLEMENT: That’s right – sets off a chain of events that actually feeds back on itself. So warming produces cloud cover change, which produces more warming, which produces more cloud cover change.

YOUNG: This does not sound good.

CLEMENT: It’s not. You know there are lots of different processes that operate in the climate system. So this is not the only one, but it does seem to indicate that clouds are an important factor in climate warming.

YOUNG: So what is this mean as we project things forward and we anticipate a more carbon dioxide and greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, more warming – what’s gonna happen?

They might not be pretty, but low-level stratiform clouds help keep the climate cool.(Photo: Andreas Christen)

YOUNG: Really?

CLEMENT: Yeah. And that one – I don’t think it’s a fluke that it was that one. This is the Hadley Centre model from the UK Met Office. They’ve spent a lot of time and effort trying to provide a better representation of the lower part of the atmosphere where these clouds lie.

YOUNG: And what kind of projections does that model generally give us?

CLEMENT: There’s a range of projections of models for the IPCC report which goes from one and a half degrees Celsius to four and a half degrees Celsius for doubling of carbon dioxide which is supposed to happen towards the end of the 21st century. So that’s about three degrees to almost nine degrees Fahrenheit change – a big wide range. The Hadley Centre model predicts a warming of nine degrees Fahrenheit, four and a half degrees Celsius. It—

YOUNG: They’re the ones at the upper end of that range.

CLEMENT: The largest amount of warming of any of the models.

YOUNG: And they’re the only ones that got the clouds right.

CLEMENT: That’s right.

YOUNG: What does this tell us about what part of that range of predictions from models we should really be looking at?

CLEMENT: I think we need to accept the possibility that that top end is not a fluke, that there might be real physical processes that can drive the climate system to that high end of the warming range. The climate system – it’s sensitive. And if we tweak it, we might be looking at a future that’s very different from what we’ve experienced in the rest of human history.

YOUNG: Amy Clement is a Professor of meteorology and physical oceanography and the University of Miami. Thank you very much.

CLEMENT: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- Read the study in the journal Science (subscription required).

- To learn more about the Hadley Center’s projections, click here.

- For more on Amy Clement's work, click here.

Entering the Plastic Vortex

(Photo: Bagtheplanet)

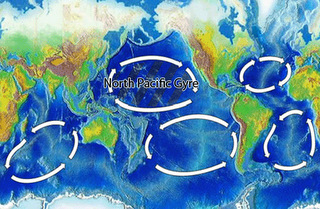

YOUNG: A pair of scientific ships sets sail this month to explore another unusual ocean phenomenon: a giant floating patch of plastic. The currents of the swirling Pacific gyre northeast of Hawaii push some four million tons of plastic into a soupy mass nearly twice the size of Texas. It’s killing marine life and adding to the ocean’s toxic burden.

The Plastic Vortex is located within the North Pacific Gyre, one of the five major oceanic gyres. (Photo: Fangz)

CROWLEY: It’s a pleasure to be on the program.

WOODRING: Great to talk to you today.

YOUNG: Well, first of all, Kaisei – what’s that mean?

CROWLEY: Kaisei means ocean planet in Japanese.

YOUNG: And that’s also the name of the vessel you’ll be sailing on?

CROWLEY: Yes. The Kaisei is 151-foot brigantine and we’ll be sailing with a group of six marine scientists, a group of about five that are there concentrating on capture techniques and what would be the most energy efficient ways of capturing the marine debris and plastics in the ocean.

The Kaisei, a 151-foot brigantine sail boat.

WOODRING: Yes, that’s correct. I’ll be on a research vessel that’s owned by Scripps Institution of Oceanography called the New Horizons. We leave from San Diego and the Kaisei leaves from San Francisco. So we’ll both be in different parts of the gyre and the good part of that is we’re getting a lot of different data points and information from different areas that haven’t been collected before.

YOUNG: So what are the main questions you think we need to answer if we’re gonna find a way to clean this up?

WOODRING: I think the main thing is gonna be how to net it or catch it in an efficient way, ‘cause new technologies exist that allow us to remediate that plastic and actually turn it into a fuel. If we’re able to do that then there’s a value to capturing that product and that can help subsidize a future cleanup effort. So that the trick is really figuring out how much volume we might get and therefore deduct in how much output we could get from a byproduct which is a fuel which could then subsidize our trip.

Mary Crowley on the Kaisei.

CROWLEY: Yes, but this is the sort of thing we’re going to test and find out so we do the best job of it. We’ve really been reaching out to people all around the world about capture techniques and about the idea of doing some passive systems where we would be able to put up netting and use sea anchors going down to a different level. And so we’d be able to use the surface current to bring us the debris. We should be able to fairly easily not involve fish or marine mammals, etc. because the debris doesn’t move except for the current. So it’s quite easy for use to get the debris and not get the ocean life.

YOUNG: Now Doug you mentioned the possibility of converting the plastic into some sort of fuel. But plastics have all sorts of toxin materials in them. How do you convert it to fuel without creating pollution in the process?

WOODRING: Well that’s a great question. And in fact, a problem especially with marine life in the gyre and marine debris is that it also is a bonding agent if you will for heavy metals, persistent organic particles that are in the ocean bind themselves to this material. So not only do you have a plastic particle, but you have millions of small bits of the POPs which are toxic. And the problem here is when the marine life eats this plastic, it may die of inability to digest the material, but it’s also these toxins that are getting into that animal or fish. And when the next animal or fish in the food chain eats that it’s going up into the whole ecosystem including into potentially what we’re eating.

So some of the new technologies that can basically liquefy and refine plastic material back into either a diesel or a heavy fuel, they have an ability to detoxify that in the process. In fact, the way that this system works is if you have a kilo roughly or a pound of plastic being put in the machine, you get about eighty percent of that back in liquid fuel form, about twenty percent is gas form. And that gas is actually going to be used to run the plant itself. So it’s a very, very good new system and there’s a value to the waste wherever it’s collected. That gives people incentive to go collect it.

The Kaisei under the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco.

WOODRING: It’s about five days from anywhere.

YOUNG: It’s almost like there’s nowhere no matter how remote you can get in the oceans where you don’t find our trash. It’s amazing.

CROWLEY: It’s very disturbing, but that’s a great deal of why I have such a passion to accomplish this cleanup. It’s sort of like this has happened in my lifetime. And I have a twenty three year old daughter and I have all sorts of young friends and I think their children won’t get to experience the same things I have unless we really take action now and create change in people’s behavior. And we need to figure out effective ways of cleanup and help the ocean. And we need everyone to help us.

YOUNG: Mary Crowley and Doug Woodring, cofounders of Project Kaisei. Thanks very much.

CROWLEY: Well thank you for having us on.

WOODRING: Thank you Jeff.

[MUSIC: Joe Satriani “Clouds race Across The Sky” from The Electric Joe Satriani: An Anthology (Sony Music 2003)]

YOUNG: Coming up – tough choices about energy on the reservation. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

Related link:

Click here to learn more about Project Kaisei.

Cheyenne May Yield to Coal

Horses grazing on the Northern Cheyenne reservation. (Photo: Dan Kraker)

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth – I’m Jeff Young.

In the southeast corner of Montana, on the isolated northern Cheyenne reservation, live some of the most determined and successful environmentalists you’ve never heard of.

Over the past four decades the Cheyenne fought powerful energy interests and the federal government to keep the tribe’s vast coal deposits from being mined. They’ve adopted some of the country’s strictest air and water quality standards. But they’ve had less success dealing with chronic unemployment and substance abuse.

Now a new tribal president is pushing coal as a way out of poverty, as Daniel Kraker reports.

[SOUND OF TRUCK DRIVING ON MOUNTAIN ROADS]

KRAKER: Jay Littlewolf’s mud-caked pickup careens up the rutted road to Badger Peak, the highest point on the Northern Cheyenne reservation.

Jay Littlewolf on top of Badger Peak outside one of the tribe's air-quality monitoring stations. (Photo: Dan Kraker)

[SOUND OF DOOR OPENING. HUMMING]

KRAKER: Littlewolf opens the door to one of the tribe’s three air quality monitoring stations.

LITTLEWOLF: Basically all three sites monitor for SO2, NOx, NO, NO2…

KRAKER: Inside the tiny trailer air analyzers hum as they measure tiny amounts of the pollutants.

[HUMMING SOUND]

KRAKER: Outside, Littlewolf points north, where 16 miles away four smokestacks puff wisps of smoke into the bright blue sky.

LITTLEWOLF: But with that plume from Colstrip, no matter what time of the year you can see it, usually in the morning you can see a brown haze in the sky there, and that’s nitrogen dioxide.

KRAKER: Colstrip is Montana’s largest coal plant. It cranks out over two thousand megawatts of electricity. When the plant’s owners wanted to expand in the 1970s, the Northern Cheyenne fought back. They became the first government to voluntarily adopt the strictest air quality standard—a class I airshed, the same as national parks.

The tribe used its new leverage to force the coal plant’s owners to install state-of-the-art pollution scrubbers, and to pay for the tribe’s air monitors.

[HUMMING SOUND]

KRAKER: Back inside Littlewolf turns on a computer to show me the data he’s collected.

LITTLEWOLF: We still get low numbers, but we measure and report in parts per billion. So we’re still being impacted because even class I has a very small increment. It doesn’t take much to impact us.

The power plant in Colstrip, just a dozen miles north of the reservation boundary. it's the largest coal-fired power plant in Montana. (Photo: Dan Kraker)

SPANG: My name is Leroy Spang. I was recently elected president of the Northern Cheyenne tribe.

KRAKER: Spang worked for three decades as a miner in Colstrip before retiring three years ago. Coal is what he knows, and it’s what he campaigned on.

SPANG: My platform was more or less coal. I guess there was a lot of people backing me for that coal, that’s how I got in.

Tribal President Leroy Spang in his office. (Photo: Dan Kraker)

LIMPY: And the revenue that would come from that coal will address our needs for money for education, housing for all our people, and a retirement fund when people reach elderly age.

KRAKER: Limpy seems unconcerned that elsewhere in the country, some are turning away from coal because of its carbon emissions.

LIMPY: It might seem way out far but they’re going to find a technique to turn that coal into some kind of energy, maybe atomic fuel. Technology is always coming up with something to use the resources underneath.

KRAKER: And Limpy says those resources could provide jobs, on a reservation where the unemployment rate is about 70 percent, and the median income only half the national average. Limpy has a good job working for the tribal government, but he says the poverty affects everyone.

LIMPY: That includes me. I have 17 people living in my home. I keep seven of my grandchildren. There’s no housing. We can’t afford to buy a house.

Outside tribal headquarters.(Photo: Dan Kraker)

LIMPY: It costs money for the companies to comply with the high standard of the clean air act that the tribe won at U.S. Supreme Court.

KRAKER: Would there be any consideration of lowering that air quality standard?

The question clearly makes Spang uncomfortable. He holds his hand up to signal he doesn’t want to answer.

[CAR SOUNDS]

WHITEMAN: We’re driving down Lame Deer, Montana, Cheyenne Avenue. We even have a four way stop downtown. What you see here is like third world conditions.

KRAKER: Philip Whiteman Junior cruises the tribal capitol’s main drag—not much more than a gas station, cafe and some boarded up storefronts. Whiteman is one of the most vocal opponents of coal development.

WHITEMAN: A lot of people think that industrial culture, gas, coal, all of that is going to bring in money, jobs, then plus they even promise Dollar Store.

Horses grazing on the Northern Cheyenne reservation. (Photo: Dan Kraker)

WHITEMAN: Look at this beauty of this land. It’s priceless. Substitute that for a dollar store? That’s what our people are faced with today.

[CAR SOUNDS]

KRAKER: Whiteman’s taking me to one of his people’s most sacred sites, Medicine Deer Rock. It's where the famous Chief Sitting Bull led Cheyenne and Sioux warriors in a Sun Dance before the Battle of Little Big Horn, where General George Custer was killed. It was a defeat that shocked America. But the victory was short-lived for the Cheyenne—they surrendered less than a year later.

[SOUND OF LIGHTER]

WHITEMAN: Bless myself with Mother Earth. Offer tobacco in the four sacred directions.

[PRAYING IN NATIVE LANGUAGE]

[SOUND OF WALKING]

KRAKER: Whiteman finishes his prayer and leads me around the rock. It’s lined with huge pictograph panels, like a giant stone art gallery. One image depicts the vision Sitting Bull had before the battle, of Custer’s soldiers dying like insects.

WHITEMAN: Look at the soldiers. Falling into the camp like locusts. They’ve got grasshopper legs.

KRAKER: Around the rock people have tied bright prayer cloths to trees, others have left offerings of food.

Prayer cloths hung around the Medicine Deer Rock. (Photo: Dan Kraker)

[TRUCK SOUNDS]

WHITEMAN: We believe that we’re still fighting in many ways, to preserve and protect our language, culture, identity, and submitting to the exploitation of our land, what little land that we have left, could be devastating to our future generations.

KRAKER: For those Northern Cheyenne who oppose coal mining, it invariably comes back to wanting to protect the land their ancestors fought so hard for. Shortly after the tribe, in defeat, was forcibly moved to a fort in Nebraska, they broke out; and in the dead of a frigid winter trekked hundreds of miles back here.

LONEBEAR: There are a lot of people who made a grave sacrifice.

KRAKER: Ben Lonebear, only 29 years old, is the tribe’s treasurer.

LONEBEAR: And I think the rationale behind not developing those resources is based on the respect for those things. And that tearing up our land that was fought for and died for really, really hits home for some people.

KRAKER: But Lonebear also knows the hardship of living in a place where there’s practically no economy.

LONEBEAR: From the treasurer’s standpoint, I believe that 85, maybe 90 percent of the money that comes into the tribe comes in the form of assistance from the federal government.

A mural painted on the side of an auto repair shop in downtown Lame Deer, encouraging young people to stay away from alcohol.(Photo: Dan Kraker)

[TRAFFIC SOUNDS]

BONOGOFSKY: It’s a false choice they’re being presented with, to be backed up against the wall, and say you have to develop your minerals or else you’re going to remain in poverty, it’s a horrible position to be in.

KRAKER: But there may be something even more fundamental at stake for many Northern Cheyenne, than whether they mine their coal or leave it in the ground, or even build wind turbines.

For people like Ben Lonebear, the key is cultural survival, not economic prosperity. If the tribe loses its language and ceremonies, he says with sadness, then they become just regular Americans, like everyone else.

For Living on Earth, I’m Daniel Kraker, in Lame Deer, Montana

The Diné Way

Navajo green jobs organizer Chelsea Chee. (Courtesy of Black Mesa Water Coalition)

YOUNG: In the Southwest, the Navajo have long allowed mining on their reservation.

Now they’re looking for alternatives.

The Navajo Nation Council is the first tribal government to approve green jobs legislation. It will support renewable energy and energy efficiency and sustainable manufacturing and agriculture based on the tribe’s traditional methods.

Wahleah Johns. (Courtesy of Black Mesa Water Coalition)

JOHNS: We’re very excited about the Navajo Nation passing this legislation. We have people that are ready to be trained in weatherization programs, putting solar panels on rooftops and given our communities being ranchers and farmers, we are looking to support families who are planning textile mill, ‘cause we have a lot of people who raise sheep.

We can use that wool to make carpets and sustainable fashion. People who are raising organic meats and foods to do gourmet foods. So this green jobs plan can help our people and individual families who do this work already but don’t have a marketing mechanism.

YOUNG: A lot of those you’re describing, they don’t sound like new fangled ways of doing things, but rather investing more in some really old ways of doing things that maybe have fallen by the wayside.

JOHNS: Yeah, I mean, this green initiative it’s really supporting, you know, these ancient ways of living as a Native people. And it’s all based on our community’s needs.

And so I think each community – it’s up to them to decide what kind of development they want, which is different than how economic development has been in the past where what happens in our backyard is dealt with the governments and the corporations.

Activists march to the Navajo Nation Council Chambers to urge their representatives to vote for the green jobs legislation. (Courtesy of Black Mesa Water Coalition)

YOUNG: Tell me a bit about the economic picture for the Navajo Nation. I read somewhere that the unemployment rate hovers around fifty percent?

JOHNS: Yup, about 54 percent. Most Native nations, it goes as high as ninety percent. I mean this is – we’ve been in the Great Depression for a very long time. [laughs]

And so that’s what we have to work with and that’s something that, you know, for me being of a younger generation and going to school and then coming back to my community, there’s little job opportunities at home.

The Navajo Council discussing the green economy legislation, which it approved by a vote of 62-1.(Courtesy of the Black Mesa Water Coalition)

You know, its frustrating to see like my uncles and my cousin brothers they are iron workers or construction workers and they have to drive to Los Angeles, Las Vegas for employment. And that’s like anywhere from a six to a twelve hour drive for them. And they come back every weekend to see their families. So I hope with this initiative that we can bring our young people back to work closer to home.

YOUNG: You grew up in the coal mining area there. Black Mesa is long been an area with a lot of coal mining. How did that affect your outlook on this?

JOHNS: You know, it’s been a challenge because that’s the largest coal strip mine up there, that Peabody Coal Company has been operating for over 30 years. And the fact that, you know, we’ve supplied the southwest with their electrical needs for over 30 years, and yet nothing has really come back to our communities.

We still have no running water. We don’t have electricity. So being a younger person and understanding the history of the deals that happened been the government and corporation, I feel like it’s my responsibility to really try to plant a seed that is gonna be good for our communities and bring healing again.

James Davis, chief of staff for the speaker of the Council, speaks to green jobs supporters after the legislation was approved. (Courtesy of Black Mesa Water Coalition)

JOHNS: Yeah, I mean that’s my goal. And using those lands that have been reclaimed after mining for something maybe a sustainability school or, you know, potential solar farm. You know, there’re so many opportunities that we can make of that land that has been used for mining.

But it’s not easy because Peabody Coal Company was given another permit December of 2008 to mine more coal. You know, that still hurts me, because Black Mesa to me is my mother. And I need my mother to be healthy and so future generations can have a good life there.

YOUNG: Now how old are you?

JOHNS: I am 33.

YOUNG: And I’m guessing that the chief organizers of this movement were your age and younger, yeah?

JOHNS: Yeah. A lot of young folks was supporting this legislation and moving this legislation.

Green jobs organizers Chelsea and Ashley Chee text the news of the successful legislation. (Courtesy of Black Mesa Water Coalition)

JOHNS: I mean there was a lot of young people involved, but there was also a lot of older folks. When we go to our communities it is mostly elders that are in our communities. And to be able to interact with them and talk about, you know, this initiative, they really understand it. They know, you know, what green living is about. [Laughs] So it’s not so much telling them like “This is the way you need to do it.”

It’s really having that respect and collaborate. You know, my identity as being a Dinéh woman and given the responsibility as I have to caretaking of land, to caretaking of family, to caretaking of my clan that I belong to. And these are the same responsibilities that a lot of Navajo young people have. And that’s part of our way of life and I feel like if we can do it on Navajo Nation, I feel like anybody can do it anywhere.

YOUNG: Wahlean Johns is co-director for the Black Mesa Water Coalition. Thanks very much.

JOHNS: Thank you.

[MUSIC: Carlos Nakai/Peter Kater “Navajo Land Blessing” from How The West Was Lost (Silver Wave Records 1993)]

Related links:

- To learn more about the Navajo Green Jobs effort, click here.

- The Navajo Nation Council on the legislation.

- Black Mesa Water Coalition

Listener Letters

YOUNG: Time now – for your thoughts.

[LETTERS THEME]

YOUNG: A correction from listener John Woolley who hears us in Palo Alto on San Francisco station KQED. Our story about the 1872 hard-rock mining law mentioned Brigham Young’s arrest for polygamy. We goofed when we said he had 103 wives. He probably had no more than 55.

Our feature on dandelions had a lot of listeners praising the flower’s power as health food. Podcast listener Sou Saephan writes “My parents and I are immigrants from Southeast Asia and eating wild plants including dandelions is a way of life. Is there a health risk to eating dandelion buds?”

We checked it out - the USDA says dandelions are indeed vitamin and mineral rich, and it’s okay to eat the buds – just look out for pesticides.

Finally, feedback from New Hampshire Public Radio listener Derek Teare, to our interview with poet Campbell McGrath. McGrath imagined the experiences of George Shannon, who strayed from Lewis and Clark’s expedition – and came across.

MCGRATH: Great herds of the buffalo all around me. Buffalo. Buffalo. Buffalo. Buffalo. Buffalo. Buffalo. Buffalo. Buffalo. Buffalo. Buffalo.

YOUNG: Mr. Teare wrote:

TEARE: Love your show, which we listen to in New Hampshire but last night’s buffalo feature caused some insomnia in our house. The piece on Shannon was extremely interesting, but you should never have let that self-styled poet just keep repeating the same 3-syllable word ad infinitum - that was sheer lunacy, lunacy, lunacy, lunacy, lunacy, lunacy, lunacy, lunacy…

YOUNG: Okay. Lunacy, polygamy, or edible greenery—whatever your thoughts, we’d like to hear them. You can reach us at comments@loe.org. Once again, comments@loe.org. Or call our listener line, at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-9988.

Just ahead - the hunt for giant pythons in Florida’s Everglades. Stay with us - on Living on Earth.

Eco-Islam

Muslim leaders gathered in Istanbul to discuss climate change.(Courtesy of Mahmoud Akef)

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young.

Green is of course the color of the conservation movement - it’s also the color of Islam. Islamic scholars gathered in Istanbul recently to blend those two shades of green with a seven-year action plan on global warming.

AKEF - We believe that all of us, all of us, not just Muslims, Muslims, Christians, Jews, everybody lives on this earth, we are in the same boat, so we have to care about this earth. All of us.

YOUNG: That’s Mahmoud Akef whose non-profit Earth Mates Dialogue Centre organized the action plan. Goals include climate change education, green cities and the grand mufti of Egypt even pledged to make his fatwa-issuing office in Cairo carbon-neutral. Mahmoud Akef says the inspiration comes from Islam’s sacred texts, the Koran, and the Hadith, the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad.

The Grand Mufti of Egypt, Sheikh Ali Goma'a, speaking at the Istanbul conference. (Courtesy of Mahmoud Akef)

There’s a hadith [speaking Arabic] means this mountain, Uhud, it is near to Mecca, and this mountain loves us and we love it. So it moves a level of caring about the mountain as a part of the environment from just to enjoy this beautifulness of the mountain to love and it’s a symbol for the other parts of the environment. We should love the environment. And when we love the environment, of course, we will take care of it. We will protect it and we will save it.

YOUNG: And then there’s another one that says that essentially you should treat a – do I understand this correctly – a palm tree as if it is your aunt? Is that right?

AKEF: Yes, yes. [speaking Arabic] means respect.

YOUNG: Uh huh.

AKEF: You should respect your aunt, of course.

YOUNG: Of course.

AKEF: So he asks the Muslims to respect and admire the palm tree, your aunt the palm tree.

[LAUGHING]

AKEF: So if you look at it as your aunt you have feeling. This is very important. You should have respect and admire the environment.

YOUNG: Yeah.

AKEF: This is what Islam and prophet Muhammad ask us to do.

YOUNG: Now you convened this conference in Istanbul to talk about the issue and come up with a plan of action. Tell me a couple of specific action items here. I read I think one where there’s a recommendation for essentially a green seal of approval, a label, that would be placed on products.

AKEF: Yes. What we call the Islamic label for products which is produced through an environmental friendly ways. And we call this tayba. Tayba means like Halal, like label putting on the food.

YOUNG: Right that it was processed in a proper way.

AKEF: Yeah. Uh-huh.

YOUNG: And who would give this seal of approval? Who would decide?

AKEF: We started by establishing an organization called MACCA. MACCA is Muslim Association for Climate Change Action.

YOUNG: Uh-huh.

AKEF: And this organization would be responsible for implementing the plan.

YOUNG: And that acronym sounds a lot like Mecca, the holy site.

AKEF: Yes.

[LAUGHING]

AKEF: Yeah, of course, we try to do sounding very similar. That means this organization coming from an Islamic principle, you know, and Islamic values.

YOUNG: Any plans for a green Hajj to reduce the carbon footprint of one’s trip to Mecca?

AKEF: Yes, we already discuss it with some people and they thought of this. And we are going to start with what we call [speaking Arabic] which is – it’s smaller than the Hajj. Cause in the Hajj are more than three, four million people attending the same place at the same time.

YOUNG: Uh-huh.

AKEF: So this is what we are working on now. And not only when they go to the holy places, but also when they go back to their countries, they will start teaching the other people.

YOUNG: Yeah, that’s a real moment of opportunity isn’t it? Because when people undertake the pilgrimage, they’re about, you know, renewing of their faith and this is a guess what we call a teachable moment, right?

AKEF: Yeah, and the potential is huge, huh? More than 1.3 billions of people around the world believe these values and this principle and if they can implement this actions, I think it will help the whole earth, you know. Because the climate change – it will affect all of us.

YOUNG: Uh-huh.

AKEF: So we should take care of this challenge. There is a hadith also if you feel the Day of Judgment is coming and you have a seedling in your hand, you should plant it.

YOUNG: Even if you think the Day of Judgment is coming you should plant a seedling?

AKEF: Yeah. [Speaking Arabic]

YOUNG: So even though things might look hopeless – still do something to make it better?

AKEF: Uh-huh, yes. If you feel it will not help – but you should do it. And we believe that all of us, we have to save this Earth.

YOUNG: Mr. Mahmoud Akef is founder and director of the non-profit organization Earth Mates Dialogue Centre. Thank you very much.

AKEF: Thank you. Thank you so much.

[MUSIC: Desert Dwellers “Whirlin Within” from Six Degrees Of The Middle East (Six Degrees records 2009)]

Related links:

- To read the declaration from the Istanbul conference, click here.

- Learn more about the Muslim 7-year Muslim Action Plan.

- Click here to learn about conservation efforts of religious groups.

- Earth Mates Dialogue Center

Hydrogen Feathers

(Photo: *CA* )

YOUNG: Coming up – saying farewell to the green, green grass of home – But first this Cool Fix for a Hot Planet from Annie Glausser.

[SOUNDS OF CHICKENS]

GLAUSSER: Hydrogen fuel may have found a lucky wishbone. The key is to pluck a chicken.

Chemical engineers at the University of Delaware say toasted chicken feathers can outperform other hydrogen storage materials, and they do it at a fraction of the cost. Hydrogen—a potential green alternative to gasoline—is a finicky element, making it difficult to store and transport. As a liquid, it has to be kept at very low temperatures. As a pressurized gas, it takes up 30 times as much space as regular gasoline.

Using chicken feathers as a storage material allows hydrogen to be kept in a much smaller space. That’s because the feathers are made up of the protein keratin, which forms hollow strong tubes. When heated, the keratin tubes crosslink and strengthen, and at the same time become more porous. This dramatically increases its surface area, so it can absorb as much or more hydrogen than expensive carbon nanotubes or metal hydrides, two popular materials for storage.

The researchers estimate that a fuel tank made of chicken feathers would only carry a price tag of about $200 dollars, while a tank made of nanotubes or hydrides could be in the millions.

Our feathered friends may help ease us off fossil fuels but the science still needs some time to roost.

That’s this week’s Cool Fix for a Hot Planet. I’m Annie Glausser.

YOUNG: And if you have a Cool Fix for a Hot Planet, we'd like to know it.

If we use your idea on the air, we'll send you a shiny electric blue Living on Earth tire gauge. Keep your tires properly inflated and you could save hundreds of dollars a year in fuel. Email coolfix—that's one word coolfix—at loe.org. Once again, that's coolfix@loe.org.

Related link:

To learn more about the energy potential of chicken feathers, click here.

Python Be Gone

(Photo: Tambaka)

And now for something completely different – pythons. Burmese pythons - in the Everglades.

This snake in the river of grass does not belong in South Florida. But it’s become a well established invasive species. Now state and federal wildlife officials are scaling up a python eradication program. They’re calling on volunteers to hunt down the snakes.

We called up one of those volunteers, Greg Graziani of Venus, Florida, who makes his living as a reptile breeder. Mr. Graziani says even though Burmese Pythons can get 20 feet long, they can be very hard to find.

GRAZIANI: Well, right now, as warm as it is they may spend a lot of time in thick brush during the day hiding because they’ve got enough heat, and that’s why we think the winter time is gonna be a better time for us. Now a lot of what we do throughout the rest of the summer will be a lot of nighttime hunts. And mainly we stick to the roads and levees because the snakes will be on the move crossing those and you’ll be able to see the animals. Unlike alligators, snakes’ eyes are very small and its not like we can go out there and spotlight ‘em and light the eyes up like people do with alligators with the reflection of the eyes. So snakes are gonna be much more difficult to find.

YOUNG: But you have managed to find at least one so far.

GRAZIANI: Yeah, as a matter of fact we took about four or five airboats out just to kinda show the press the terrain that we were dealing with. Myself and Sean Hefleck, one of the other hunters, was walking down a boardwalk and Sean was looking off to the right side of the boardwalk while I was watching the left side, which is when I spotted the tail of a Burmese python going under the boardwalk. So I immediately just dropped down on the snake and grabbed the snake by the tail before we could get under the boardwalk and Sean Hefleck jumped into the marsh right there and as I pulled the snake out we worked out way up until he was able to get the head under control and ended up pulling out a nine foot eight inch female Burmese python.

YOUNG: Holy cow. So let me get this straight – the hunting technique is you spend a lot of time trying to find a snake, and then when you find it you basically just jump in the swamp and wrestle the thing down?

GRAZIANI: Depending on the size. I mean a lot of times we just simply reach down and pick them up. They’re a very slow moving snake. They’re -

YOUNG: Yeah but it’s almost ten feet long!

GRAZIANI: Yeah. That’s –and that’s you know about an average size Burmese python. I know it seems really spectacular, but when you’ve been doing this for over thirty years, its just another snake.

YOUNG: So tell me about your experience with snakes. How did you learn so much about snakes and what motivates you?

GRAZIANI: You know, I started when I was seven years old. I grew up in the city of Pembroke Pines down in Broward County Florida, which is very close to where this problem is occurring. And I was taking care of a neighbor’s house, bringing the mail in, feeding the cat, that type of stuff. And it was dusk one night, I went over and thought there was a big night crawler on the front porch. I really couldn’t see. I reached down and grabbed it, and it bit me. [Laughs] And from that point on it just intrigued me. I started getting into corn snakes as a youngster and anything that I could catch. In the late 80s I realized that people were breeding these things and it’s become a large market in the pet trade.

YOUNG: So you know the pet business pretty well. What’s the culpability there for these pythons ending up in the Everglades in the first place?

GRAZIANI: Well, there’s a lot of theories. Unfortunately some of the politicians have been really pounding it into people that, you know, irresponsible pet owners have let these animals lose. They really make it sound like people are driving down in droves to make sure their snakes can survive in the Everglades.

YOUNG: Uh-huh.

GRAZIANI: And we just don’t believe that to be true. There has not been a single documented case where they’ve actually caught anybody releasing snakes. And we believe the devastation of Hurricane Andrew is what released the population that we’re now having a problem with. And it seems that there has been a study done, a DNA study, that shows these animals are very closely related which would point to a single incident that put them out there at one time.

YOUNG: So, this might very well be yet another legacy of Hurricane Andrew.

GRAZIANI: Yes.

YOUNG: Wow.

GRAZIANI: Yes.

YOUNG: And is it fun hunting snakes in the Everglades?

GRAZIANI: I think it’s extremely exciting. I mean, again, I wish they weren’t there. But very few people can go python hunting in the United States because they’re just not here.

YOUNG: Can this work? Can you possibly, you know, get rid of the pythons once they’ve become so well established in a place as wild and tough to penetrate as the Everglades?

GRAZIANI: You know there’s a lot of theories on that. And what we want to find out because it is really not known at this point is, are these animals a serious threat to the ecosystem in the Everglades? Do we need to work on a total eradication? Do we simply need to work on controlling the population of these animals? Or are they not a problem at all? By doing the gut content and finding out which animals they’re eating and trying to do surveys on other animal populations out there, we’re gonna hopefully find out, you know, what we need to do and if our efforts are actually contributing to restoring the Everglades.YOUNG: So, you say you’re checking the gut content of the snakes. Obviously when you catch them, you kill them, right?

GRAZIANI: Yeah. That is not something that as hunters and as python breeders that we particularly want to do. But it is part of the criteria for this program. Unfortunately that is the downside, as you know, a snake lover myself. Would I rather than somebody else handle the euthanization process, definitely. But, that’s just something we have to do.

YOUNG: Greg Graziani, reptile breeder turned python hunter. Thanks very much for your time.

GRAZIANI: You’re welcome. Thank you.

[MUSIC: Ross Aubrey “Indian Python” from year Of The Snake (Liafeht Publishing 1998)]

YOUNG: As they say the grass is always greener on the other side, but commentator Pat Priest of Athens Georgia prefers what’s on her side of the fence.

PRIEST: My name was drawn at a raffle recently, and I learned I'd won a free month of tanning! As a teenager I would have been thrilled, but . . . now . . . in my fifties? I know better! I felt awkward turning it down, but then other people passed on it, too! We've learned to just say no to a cigarette, veal . . . and tanning.

But meanwhile, day after day, I watched a neighbor lay out about a half acre of new sod . . . sod! It looks pretty if you weed out thoughts of the water necessary to sustain it. Turf guzzles so much water that the city of Cary, North Carolina is among a growing number of places offering buy-back programs to homeowners who will rip it out.

A half-acre needs tens of thousands of gallons of water yearly. But the problems are more deeply rooted than simply conserving water. Perfect grass really is much like the perfect tan, which may look like a sign of robust health but more often is evidence of damaging practices.

The green, green grass of home is usually the result of pesticides and herbicides that kill creatures in nearby streams when storm water flushes out the toxins.

Fertilizers also damage aquatic environments and the mining of phosphate rock for fertilizer has poisoned the water in places as far flung as Idaho and Florida.

And what would ancient cultures think and those in the future for that matter, to see us walking around in circles mowing grass?

The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that lawn mowers use 800 million gallons of gas each year. And the emissions cause five percent of the air pollution in the US.

So this year I decided to cover over my grass. A friend helped me lay down recycled paper lawn bags.

We covered the paper with mulch made from invasive species such as privet and Russian olive. These layers will improve our hard clay soil. When it’s cooler, I’ll put in lots of native plants. They’re like a big “Welcome” sign for pollinators and other species whose habitat is disappearing.

To undo my lawn yard by yard was as labor intensive initially as my neighbor's sod laying. But I don’t need to mow or use chemicals now that I'm finished. My yard doesn’t look like a golf course, but it’s a safe haven for my family, dogs, and wildlife.

By undoing my lawn, I’m overturning convention and commonly held aesthetics to stave off the unraveling of the irreplaceable web of life on Earth.

[MUSIC: Robyn Hitchcock “Chinese Water Python” from Eye (Yep Roc Records 2007)]

YOUNG: Writer Pat Priest tends her brown lawn in Athens Georgia.

Related links:

- Click here to learn more about the Interior Department’s plans.

- For more information on the Burmese python, click here.

Green Brown Lawn

Writer Pat Priest

YOUNG: As they say the grass is always greener on the other side, but commentator Pat Priest of Athens Georgia prefers what’s on her side of the fence.

PRIEST: My name was drawn at a raffle recently, and I learned I'd won a free month of tanning! As a teenager I would have been thrilled, but . . . now . . . in my fifties? I know better! I felt awkward turning it down, but then other people passed on it, too! We've learned to just say no to a cigarette, veal . . . and tanning.

The green grass of Pat Priest's driveway before it was overturned.

A half-acre needs tens of thousands of gallons of water yearly. But the problems are more deeply rooted than simply conserving water. Perfect grass really is much like the perfect tan, which may look like a sign of robust health but more often is evidence of damaging practices.

The green, green grass of home is usually the result of pesticides and herbicides that kill creatures in nearby streams when storm water flushes out the toxins.

Fertilizers also damage aquatic environments and the mining of phosphate rock for fertilizer has poisoned the water in places as far flung as Idaho and Florida.

And what would ancient cultures think and those in the future for that matter, to see us walking around in circles mowing grass?

The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that lawn mowers use 800 million gallons of gas each year. And the emissions cause five percent of the air pollution in the US.

The brown, mulched lawn requires no water or chemicals.

We covered the paper with mulch made from invasive species such as privet and Russian olive. These layers will improve our hard clay soil. When it’s cooler, I’ll put in lots of native plants. They’re like a big “Welcome” sign for pollinators and other species whose habitat is disappearing.

To undo my lawn yard by yard was as labor intensive initially as my neighbor's sod laying. But I don’t need to mow or use chemicals now that I'm finished. My yard doesn’t look like a golf course, but it’s a safe haven for my family, dogs, and wildlife.

By undoing my lawn, I’m overturning convention and commonly held aesthetics to stave off the unraveling of the irreplaceable web of life on Earth.

[MUSIC: Robyn Hitchcock “Chinese Water Python” from Eye (Yep Roc Records 2007)]

YOUNG: Writer Pat Priest tends her brown lawn in Athens Georgia.

On the next Living on Earth: The United Kingdom wants more renewable energy – including tidal power. But a plan for a huge wall in a river mouth is making waves.

WRIGHT: Put a barrage across like that, the barrage's effectiveness will not be a hundred years, it probably will only be ten years. It'll just be mind-boggling. It'll just silt the whole place up and turn the whole place into a vast bog.

YOUNG: Harnessing the River Severn, next time on Living on Earth.

Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Bruce Gellerman, Ingrid Lobet, Helen Palmer, Jessica Ilyse Smith, Ike Sriskandarajah, and Mitra Taj, with help from Sarah Calkins, Marilyn Govoni, and Sammy Souza. Our interns are Annie Glausser, and Lisa Song. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Our executive producer is Steve Curwood. You can find us anytime at loe.org.

I’m Jeff Young. Thanks for listening

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth