June 26, 2015

Air Date: June 26, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Pre-Natal Exposure to DDT Linked To Breast Cancer

View the page for this story

A new study that uses blood samples collected over 50 years ago finds that women who were exposed to DDT in the womb have a four-fold increase in breast cancer risk today. Study author Dr. Barbara Cohn of the Public Health Institute describes the finding to host Steve Curwood and suggests how we should think about DDT and the risks of thousands of other chemicals. (07:15)

BPA Exposure Associated With Poor Parenting

View the page for this story

Humans today live in a sea of chemicals, and we are just beginning to understand how they affect our health. The endocrine-disrupting chemical Bisphenol-A has been linked to cancer, but new research from the University of Missouri found that the common substance seems to impair parenting behavior in mice. Scientist Cheryl Rosenfeld discusses the finding and its implications with host Steve Curwood. (07:50)

Mule Deer Poachers Slip Past The Law

/ Tony SchickView the page for this story

Wildlife trafficking and crime is a global problem and the Pacific Northwest is not immune. While a small law enforcement and judicial team polices the large territory of Washington and Oregon states for wildlife infractions, limited resources, budget woes and loose laws allow poachers to evade penalties. Now, as EarthFix's Tony Schick reports, further underfunding and low prioritization of wildlife crime cases threaten to exacerbate the issue further. (04:25)

Drones Stymie Rhino Poachers

View the page for this story

Poaching is a threat to the survival of rhinos worldwide, and anti-poaching efforts have always been one step behind. Now, park rangers in South Africa have a leg up. John Petersen from the Air Shepherd program tells host Steve Curwood how the power of predictive analytics combined with drone technology could help to rescue the rhinos. (07:10)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood how the U.S. Open went green by opting for brown grass and shares a positive benchmark for the Hudson River. He also takes a look back at some powerful journalism that predicted Hurricane Katrina’s damage three years before ‘The Big One’ hit New Orleans. (04:20)

BirdNote®: How Much Birds Sing

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Worldwide, songbirds sing to claim territory and protect mates, but each species does it with its own style. Some tweet a short phrase and others warble on and on. As BirdNote’s Michael Stein reports, some species want to make sure their message is heard, singing thousands of times a day. (02:00)

The Evolution of Birdsong

View the page for this story

Birdsong is an intricate communications system: each tweet, chirp, click and trill confers a message. But as Michael Webster, Director of the Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, tells host Steve Curwood, many factors, such as the environment, migration, climate change and pollution are influencing the evolution of birdsong in interesting and unique ways. (10:35)

Purple Martins: Extroverts of the Air

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

East of the Mississippi, purple martins gather. Writer Mark Seth Lender watches a handful of purple martins as they catch insects, squabble, and converse, and ponders what they could be chattering on about. (02:45)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood,

GUESTS: Barbara Cohn, Cheryl Rosenfeld, John Petersen

REPORTERS: Tony Shick, Peter Dykstra, Michael Stein, Mark Seth Lender

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Early exposure to the banned pesticide DDT is linked to breast cancer decades later, and new research shows a four-fold increase for women exposed in the womb.

COHN: This is the very first study where we've actually been able to measure in utero exposure to an environmental chemical — in this case, DDT — and look forward 54 years at the risk of breast cancer for women who were exposed in utero.

CURWOOD: Also, how pollutants like BPA in the environment are messing up some birds.

WEBSTER: Starlings who are exposed to that contaminant sing more complex and sexy songs that the females seem to like better. Bisphenol A also affects their immune system, so the females are being attracted to the lower quality males.

CURWOOD: We have those stories, and much more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada, “Zoetrope,” In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country, Warp Records 2000]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

[THEME]

Pre-Natal Exposure to DDT Linked To Breast Cancer

CHDS keeps the study’s blood samples, gathered from women and their descendants beginning in 1959, deep-frozen at negative 80 degrees Celsius. (Photo: Paige Cowett/WNYC with permission)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. DDT was banned in the United States over 40 years ago, a decade after Rachel Carson first raised the alarm about the pesticide in Silent Spring. And DDT has long been suspected in the human breast cancer epidemic, but research in the 1990s could not demonstrate a credible link. In 2007 Dr. Barbara Cohn, of the Public Health Institute in Berkeley, California, talked to us about her study that linked pre-puberty exposure to DDT as a risk for breast cancer in adulthood, using indirect epidemiological evidence. Well, now Dr. Cohn joins us again, to explain how her team has taken this research a giant step further with hard evidence that matches DDT exposure in utero to elevated rates of breast cancer when women hit their 50s.

COHN: This is the very first study that I'm aware of where we have actually been able to measure in utero exposure to an environmental chemical — in this case DDT, which was a pesticide — and look forward 54 years at the risk of breast cancer for women who were exposed in utero. We found that women who had the highest levels of exposure, in the top 25% of exposure, had more than a 3.7 fold, almost a fourfold increase in risk of breast cancer by the age of 52.

CURWOOD: Why does the age of exposure matter with respect to breast cancer risk?

Willie Mae Washington, at left, became one of the first participants in the study more than fifty years ago. Her daughter Ida Washington, now 52, is in the second generation of the study. (Photo: Lindsey Konkel/Environmental Health News, CC)

COHN: Well, we know from animal studies, and we have other clues from humans as well, that there are particular periods in life when the breast is most vulnerable to something that might perturb its development and be related to breast cancer later on. One of those periods is in utero when the breast is forming. Another one of those periods is in puberty, or leading up to puberty, during the hormone storm of that time. Another period is pregnancy itself, when the breast is in a different state, preparing for lactation. Another period is likely when the breast is returning to its pre-lactation state, after pregnancy or after nursing has been completed. And then, finally, during the last hormone storm in the perimenopausal period, may be another period of risk. Different aspects are happening at each one of those points in time, and we expect the exposures during those times may have variable effects depending on when they happen.

CURWOOD: All these periods you've mentioned, as you say, are times of very intense levels of hormones. You call them “hormone storms.” Tell me a little more about that.

COHN: Well, we've long suspected that there are a number of environmental chemicals, and perhaps pharmaceuticals and other exposures, that can interfere with the signaling systems that hormones participate in. These chemicals that can interfere with these hormonal times are often called endocrine disrupters, and they may perturb the natural and normal signaling that is going on at these critical periods and alter the tissue, the cells, and even perhaps the instructions about how DNA and genes are turned on and off, so that, later in life — even much later — the tissue may have a higher risk to become cancerous.

CURWOOD: So what's next in this area of research?

COHN: Next, because there are not very many human studies with a 54 year follow-up like we have, will have to be done in the laboratory, where experimentalists can actually reproduce the timing of exposure and the doses that are analogous to what we found in our study, to first confirm whether they see changes in the breast or the mammary glands of animals that are similar to what we would expect based on our study; and, second, to see if they can understand mechanisms. Human studies never can prove causation. We don't do experiments on humans. And so it's always possible that there are some other chemicals or other exposures that underlie the DDT connection that we've seen. Animal studies are required to determine more carefully whether there's causation.

Dr. Cohn collaborates on her research with Dean Jones, professor of medicine and Director of the Clinical Biomarkers Laboratory at Emory University. Using a special high-resolution mass spectrometer, Jones and his colleagues are able to scan a drop of blood for tens of thousands of chemicals. (Photo: Paige Cowett/WNYC with permission)

CURWOOD: Now, DDT was banned more than, what, 40 years ago here in the United States. How concerned should Americans be about DDT today?

COHN: Our present is very much affected by our history, and what we're wondering is how far back we have to go for our history of exposure, to understand our present and our present risks. So here we have women who are very much alive, born in the 1960s, who are just beginning to face the risks of breast cancer that come with age. So that's the first answer to your question. The second answer is the World Health Organization has promoted the use of DDT for public health purposes in countries where malaria is still a very significant public health problem. And my research does not change the potential benefits for the use of DDT to control malaria, because malaria is a terrible public health concern, particularly for women and children. But it does change the assessment of potential risks of exposure to DDT. We have some more experience since the time the World Health Organization essentially re-authorized the use of DDT for malaria control, and the next step that people are talking about taking are ways to do a better job of protecting that vulnerable population, and still do what has to be done to control malaria.

CURWOOD: And for an individual listening to us who is saying, “Hey, how can I find out if I was exposed to DDT in utero,” what can and should she do?

COHN: A woman cannot go back and change the past, but she can change her future. And a recommendation is to look to the lifestyle guidelines that the American Cancer Society provides, work with her doctor to talk about what screening is appropriate for her, and also consider whether it might be right for her to try to avoid unnecessary exposures to chemicals that might be suspect, but that we don't really know about yet.

Dr. Barbara Cohn is the Director of the Child Health and Development Studies at the Public Health Institute in Berkeley, California. (Photo: courtesy of Dr. Barbara Cohn)

CURWOOD: Dr. Cohn, what do your findings tell us about what we need to be thinking about today, about the potential risks of the many chemicals we use?

COHN: Well, I believe the study is very much a proof-of-concept study. It's very unlikely that we'll be able to ever study the 80,000 chemicals that are out there, some of which may have the potential to increase risk for breast cancer and other health problems as well. Since we cannot do that, perhaps what the study is saying, that because there is this potential for these chemicals to do harm, we have to turn to the public policy arena to discuss what level of risk society is willing to take, and to examine carefully both the benefits and the risks of using certain classes of chemicals in our modern life.

CURWOOD: Dr. Barbara Cohn is an epidemiologist and Director of the Child Health and Development Studies at the nonprofit Public Health Institute in Berkeley, California. Dr. Cohn, thanks so much for taking the time today.

COHN: You’re welcome. Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- DDT study: “DDT Exposure in Utero and Breast Cancer”

- “Breast cancer and the environment: Studied for half a century, these women are ‘a national treasure’”

- Our story on DDT exposure during youth and breast cancer

- “What Causes Breast Cancer? These Mothers and Daughters May Hold a Clue”

- About Dr. Barbara Cohn

- “Pesticides: Toward DDT-Free Malaria Control”

- WHO statement: “The use of DDT in malaria vector control”

- Reducing the Risk of Breast Cancer

BPA Exposure Associated With Poor Parenting

The California mouse was perfect animal model for this research because the species is monogamous and biparental. (Photo: Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Well, though it’s banned in the US, DDT persists in the environment, and it’s a pesticide that, as well as being linked to cancer, disrupts hormones. It’s another of the thousands of chemicals ubiquitous in our modern world that affect our bodies in ways we are only beginning to understand, including brain development and behavior. One chemical that’s gotten a lot of attention recently is Bisphenol A or BPA, and a new mouse study suggests that the chemical could have adverse impacts on parenting behavior. Joining us now to discuss the study is Cheryl Rosenfeld, a Biomedical Sciences Professor at the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Missouri. Welcome to Living on Earth, Cheryl.

ROSENFELD: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: So, first of all, remind us, what is BPA and where is it found?

ROSENFELD: Well, Bisphenol A is considered an endocrine disrupting chemical, and it's found essentially everywhere, because it’s in our everyday items. It's in our plastics, in our cardboards, it's even used in dental sealants. And the problem with Bisphenol A is it does not degrade in the environment, so it actually can bioaccumulate. They've done several studies looking at whether we can find it in the water and in terrestrial sources, and in almost all aquatic sources tested today there's been measurable amounts of Bisphenol A.

Concerns about BPA have prompted companies to take the chemical out of many common baby products. (Photo: Alicia Voorhies, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: What are the health effects that have been demonstrated?

ROSENFELD: The health effects are many. These include cancers, reproductive deficiencies in males and females, neural behavior deficits, immunological problems, to list just a few.

CURWOOD: So, as I understand it you wanted to look at the impact of Bisphenol A, BPA, on parenting behaviors, and you did a study using mice. Why did you use the California mouse?

ROSENFELD: So we decided to use the California mice for these studies because unlike regular laboratory mice and rodents, they exhibit monogamy and they're biparental. In the past studies they've only looked at maternal behaviors because they could not assess paternal effects, because in laboratory mice and rats, the dad does not play any parental investment.

CURWOOD: But in the California mouse, dad cares.

ROSENFELD: That's correct. Dad does care, and he has to care very much because the survival of his offspring are dependent upon basically receiving parental care from both mom and dad.

CURWOOD: So, tell me about your study. What exactly did you do?

ROSENFELD: So what we did was, we developmentally exposed both males and females in utero and during the postnatal period to Bisphenol A in environmentally relevant concentrations. So we then took those F-1 offspring that were developmentally exposed to Bisphenol A and we did various combinations essentially where we would have: either they were both controls, or mom exposed to BPA, or dad was exposed to BPA or both.

CURWOOD: So what did you find? How did Bisphenol A affect the parenting behavior in these mice?

ROSENFELD: Well, similar to other studies with laboratory mice and rats, we found that developmental exposure to Bisphenol A reduced the maternal investments — time spent nursing, time spent in the nest, decreased if she was exposed to BPA. Likewise, and this is what is novel, we found that the dads who were also exposed to Bisphenol A spent less time in the nest with his pups. But what was really intriguing to us is if both parents were developmentally exposed to BPA, we had heightened effects. Essentially they both reduced their parental investment. We also found that control females who were paired with males who had been exposed to BPA reduced their parental investment, as assessed by time spent nursing and in the nest with the pups. And that was quite surprising to us, because she herself was a control, so she obviously could engage in normal parental behaviors, but it was almost as if she could sense the compromised state of her partner and she was going to reduce her parental investment in his offspring.

CURWOOD: So it's kind like in the human family, if dad is off drinking heavily and blowing all the money, mom says, “Not much I can do.”

ROSENFELD: That's kind of like a defeatist kind of attitude perhaps, but the thing too in rodents, you have to think about is they obviously want to save some of that energy back for the next litter. So she might say, “well, look, he's not the best partner, and what if I can get a better partner? I want to invest in those offspring. So I'm going to save some of my energy resources for subsequent generations.”

CURWOOD: Well, wait, I thought they were monogamous?

ROSENFELD: They are, but if the partner dies in the wild, then they will pair up again with another male or female.

CURWOOD: So if they die or if they're a deadbeat apparently.

ROSENFELD: [LAUGHS] Maybe so. We haven't tested that hypothesis yet.

CURWOOD: So stepping back for a moment, Cheryl, what surprises you the most about your results?

ROSENFELD: Well, I think, essentially, the fact that paternal behaviors, just like maternal behaviors, are vulnerable to endocrine disrupting chemicals. This is what's unique because nobody has looked at how extrinsic factors like endocrine disruptors, paternal diet, stress, could affect his parental investment. And we need to start thinking about how those findings might relate to humans, because there's not been a single study to date that has looked at how Bisphenol A, or any EDC exposure, can affect parenting behavior in humans. And I think to me the long-standing consequences of having reduced parental care are incredibly important.

CURWOOD: Now, parenting behavior for humans seems like something that has to do a lot with culture and socioeconomics. How relevant do you think your findings are for humans?

ROSENFELD: So, you're correct, social and economic issues all play important roles in parenting, but if it comes down to it, it's actually guided a lot by what is called neuropeptide hormones in the brain. So let's say when the woman gives birth, she has a surge of what we call oxytocin. That lets the milk down in the breast and then the infant can feed. But it also, too, it really solidifies the maternal-infant bond. And it is now clear that even dads who just had their son or the daughter born, they also get a surge of oxytocin. And the same thing happens in our animal models. These parenting behaviors that we've been measuring are guided by hormones like oxytocin.

CURWOOD: So if that process is interfered with, perhaps the bonding with the child is interfered with.

ROSENFELD: That's our hypothesis. That's what we’ve been looking into, in terms of how these chemicals can be affecting these hormones like oxytocin and related ones.

CURWOOD: BPA’s been removed from a number of products, but you note that it accumulates in the environment. So I'm wondering, to what extent do we continue to be exposed to BPA, even if we don't use BPA-containing products?

Cheryl Rosenfeld (Photo: University of Missouri)

ROSENFELD: Because it is in the environment, and it cannot degrade easily, our exposure is almost guaranteed. But that still does not mean that we should not reduce our exposure at this point. The FDA has banned it from the baby products. That's one possible mechanism by which many infants can be exposed to it; however, it still does not address the two primary routes of exposure, and that is the environment and the pregnant mother. So that pregnant mother is being exposed Bisphenol A while she's carrying her offspring, and that's probably the most critical period for a lot of the organ systems, including the brain.

CURWOOD: And Bisphenol A is just one out of many, many, many chemicals that have endocrine disrupting.

ROSENFELD: That's correct, and so I think we need to look at other ones, including heavy metals, air pollutants, nanoparticles — that's become very prevalent now in our environment as well — and decide if they affect maternal and paternal behaviors.

CURWOOD: Dr. Cheryl Rosenfeld is a Professor of Biomedical Sciences at the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Missouri. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Professor.

ROSENFELD: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- Read the study in PLOS ONE

- About Cheryl Rosenfeld

CURWOOD: There’s more on both these studies at our website, LOE.org. Coming up… a new use for drone technology to save endangered rhinos. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Punch Brothers, “Passepied (Debussy),” The Phosphorescent Blues, Mercury 2009]

Mule Deer Poachers Slip Past The Law

Darin Bean looks through binoculars at Twin Lakes while chatting with La Pine resident and fisherman Larry Archer. Bean cited Archer in the past for shooting a wildlife decoy. (Photo: Tony Schick, OPB/Earthfix)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Illegal Wildlife trafficking is a massive problem that’s bringing many species to the brink of extinction. Rhinos, for example, or elephants, which are sought for their valuable horns and tusks. But it’s not just a problem in Africa and Asia – here in the US, there are also species with horns that are ripe for lucrative poaching.

For example, the trophy antlers of the Western mule deer can fetch a thousand dollars or more, and with strict limits on hunting, poachers are often meeting the demand. In Oregon, there have been some recent arrests for mule deer poaching, but resources to catch poachers are spread very thin, and penalties aren’t high enough to be much of a deterrent. Still, Fish and Wildlife troopers are doing their best to protect dwindling numbers of mule deer.

From Central Oregon, Tony Shick, from the public media collaborative EarthFix, has the story.

Oregon State Fish and Wildlife troopers James Hayes, left, and Darin Bean patrol several thousand square miles in central Oregon, where mule deer are in decline. (Photo: Tony Schick, OPB/EarthFix)

BEAN: “Hello .... State Police ...”

SCHICK: Oregon Fish and Wildlife Trooper Darin Bean is searching a home in the backwoods of La Pine, Oregon.

BEAN: “Boy, there’s a lot of little rooms in this place …”

SCHICK: A few months ago he caught a man here who illegally shot and stashed the carcass of a breeding female mule deer. He’s following up after a missed court date.

BEAN: “This is where they had the deer.”

SCHICK: He peeks around a dark doorway and shines his flashlight into a stained bathtub.

BEAN “You can see there’s still deer blood ... in the spare bathroom, ya know.”

SCHICK: Mule deer have been in sharp decline here, and poaching is one reason why.

It turns out at there are as many deer being killed illegally as there are by law-abiding hunters.

Declining budgets have left Oregon and Washington with fewer Fish and Wildlife troopers than they had in the 1980s. Both states are poised to lose more troopers this year.

James Hayes examines the damage on a car he suspects was involved in a hit-and-run. Budget cuts in local law enforcement has led to some Fish and Wildlife troopers handling more general law enforcement. (Photo: Tony Schick, OPB/EarthFix)

Bean and his partner James Hayes are the only Fish and Wildlife officers patrolling more than five thousand square miles. And, they have less time to spend finding poachers as they used to. Their workload now includes more general law and time spent on safety checks for boats and ATVs.

BEAN: “Yeah, the days of just solo fish and wildlife are, you know … not anymore.”

SCHICK: On one shift alone, Bean and Hayes handled arsons, hit-and-runs and burglaries.

They still go hard after big poaching cases, and they think Gene Parsons is one of those.

BEAN: “Near as we can tell, that guy killed a tremendous amount of deer.”

SCHICK: They arrested Parsons in January and so far have charged him with 15 counts of violating Fish and Wildlife laws. Months later, he has been indicted but has not yet stood trial. He didn’t return phone calls.

BEAN: “He’d shoot 5-6 deer a night. And he’d cut the antlers off. With a chainsaw. And bring em home, and then a lot of times he would just, as near as we could tell, sell the antlers.”

SCHICK: Where poachers sell remains a mystery to them. But they recently received a tip about an antler dealer. He’s said to be in possession of several thousand dollars worth of stolen horns.

Hayes says if they can connect Parsons or other suspected poachers to this dealer, that could mean additional charges like racketeering. Penalties for poaching alone aren’t always a big deterrent.

Fish and Wildlife troopers from Bend and La Pine wait outside the property of an antler dealer in Central Oregon. They need his help to track down some stolen antlers and connect suspected poachers to antler sales. (Photo: Tony Schick, OPB/EarthFix)

HAYES: “If there’s no jail time involved and it’s just monetary small fines, they’re not likely to quit … for your real criminals.”

SCHICK: Some Northwest counties prosecute Fish and Wildlife cases aggressively. Others dismiss a high number of cases or reduce them to small fines. Many lack the resources to go hard after poachers.

Just ask Ulys Stapleton, the lone Lake County prosecutor who handles a lot of cases from Bean and Hayes. His jail has 17 beds and he says most are claimed by people in drug-related crimes.

STAPLETON: “I understand why officers may be frustrated, but you don’t have the resources to throw everybody in jail. So what I try to do is I hit em up with a fine.”

SCHICK: The sun is setting on a windy day in Lake County by the time Hayes stops his truck at the antler dealer’s gate. Bean pulls up minutes later, along with troopers from Bend and John Day. They’re also tracking sales from poaching suspects.

HAYES: “Not home. Gate’s locked — padlocked. Looks like one set of tire tracks came out of there, maybe this morning.”

SCHICK: They meant to come earlier, but Bean was called to a burglar alarm.

They wait outside the property for a few tense minutes, then the dealer returns a call to one of the Bend troopers.

BEAN: “Well, what’s the word?”

SCHICK: He’s gone for the evening. The antlers have moved on. His sale records aren’t at the house, either.

RING: “I said, I’m trying to run down some stolen horns, you know where they at? Who do you sell them to? He said ‘I’m running a business and I’m not in the business of telling you where I’m selling my stuff.’”

SCHICK: Out of options, they load up and they roll out. And the hunt goes.

I’m Tony Schick in La Pine.

CURWOOD: Tony reports for the public media collaborative, EarthFix, and there are videos at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- "When Police Ranks Are Thin, Wildlife Crime Often Does Pay" EarthFix/OPB report

- NW Wildlife Enforcement, in Five Charts

- Oregon DFW study about hunting and poaching rates

- Oregon DFW Hunting

- ODFW Budget is squeezed

- Washington state DFW's Finanical status

- Gene Parsons arrested for unlawful take of mule deer

- Parsons charged for wildlife law violations

- Support to strengthen penalties for wildlife crimes

- One of Washington's largest illegal wildlife traffickers

- Oregon Public Broadcasting "Wildlife Detectives" series

Drones Stymie Rhino Poachers

Staff members of South Africa-based UAV & Drone Solutions hold one of their drones. UAV supplies the drones and the ground crew for Air Shepherd. (Photo: Michael Romondo)

CURWOOD: Well, when it comes to poaching it’s not all bad news — in fact, for some endangered rhinos, there is an encouraging development to report. This good news comes in the wake of record number of rhinos slaughtered in 2014 by poachers in South Africa — an estimated 1200, with more taken elsewhere on the continent.

Traditional Asian doctors believe that rhino horns have curative power, and market demand has driven some rhino species to the edge of extinction. But that demand is now running into a high-tech enforcement system just launched in South Africa to protect these large mammals.

The Air Shepherd uses military-style computer analytics to identify poaching hot spots, and then sends silent drones equipped with night vision to track down poachers, who like to work after dark, when people can’t see them. John Petersen, Chairman of the Charles A. and Anne Morrow Lindbergh Foundation, that’s spearheading this effort, joins me now — welcome to Living on Earth, John.

PETERSEN: Hi, Steve, nice be here.

CURWOOD: So you came up with the idea of using drones. How did you decide where to fly these drones?

PETERSEN: Well, that's the important part of this, because some of these game parks are the size of Connecticut. And if you've got a little model airplane and you're trying to figure out where to fly that airplane in that size of a piece of land, and you don't have any idea about particularly where to fly, then you're wasting your time. That's where the experience of the University of Maryland comes into play, because they have developed a predictive analytic tool to tell us on a daily basis where the animals are likely to be and where the poachers are likely to be.

CURWOOD: Predictive analytics? how does that work?

Launching an Air Shepherd drone. (Photo: UAV & Drone Solutions)

PETERSEN: Well, it's interesting because the University of Maryland got a contract a number of years ago with the Department of Defense to try to predict where roadside bombs were going to be in Afghanistan and Iraq. And by using historical information and topography and routes and infrastructure and all those kinds of things, over time they got to become very highly accurate predicting where these bombs were going to be.

The head of that program, Dr. Tom Snitch, was very interested in the wildlife conservation area, and he figured out that you could take the same basic algorithms and repurpose them into the anti-poaching. And that's what we do, we've joined the most effective operational capability on the ground with this super computer-based predictive analytics, and where we've tested it, it stops poaching.

CURWOOD: What's the data that goes into his computer model here? Are you looking for where the rhinos are? Are you looking for where the poachers are, do you combine? How does this work?

UAV & Drone Solutions’ mobile unit and drone fleet in Delta Park, Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: UAV & Drone Solutions)

PETERSEN: The poaching problem is all dependent upon where the animals are, of course. And so you build databases that have all of the topography of the land that you're looking at. It has all the historical information about where poaching has happened in the past, so that you get patterns on where they happened. You figure out the time of the day and the time of the year, and whether it was wet and what the weather was like, and whether there were waterholes close by, and whether there was a full moon, and how close to roads they were, and other such things. And the combination of all of this allows you to say with a high degree of confidence that, tonight, you should fly your aircraft over the top -- you're going to know that this is where the poachers will come if they come tonight.

CURWOOD: How exactly would this work on a given day?

PETERSEN: The computers work all of the data and come up with a flight plan that says, tonight, here's where the problem is, and here's how you should fly your drone. And we download the flight plan, and you then preposition the rangers in that area and you launch the drone, and it autonomously automatically starts on this flight. And you monitor that information in the operations center, which is a mobile center that drives around out in the bush and launches and recovers the aircraft. And you see and look for both animals, and you look for the possibility of human beings. And, in most cases, they're in cars, and they drive down the road and they stop. Then you can alert the rangers, because they're positioned close by, they can get there in a hurry and they can capture the person and arrest them before they have a chance to kill the animal. And then you take all of the information of that day, all the environmental information, the information about the locations and so on, upload it to the computer as additional data, and it makes the database more robust.

The white rhinoceros is actually grey; its northern subspecies is critically endangered. The southern subspecies is the most abundant rhino in the world, with over 20,000 individuals. South Africa is home to the largest population of rhinos in the world. (Photo: Ikiwaner, Wikipedia CC)

CURWOOD: So, this is a combination of folks on the ground, the drone being flown in real time, somebody looking at the data and giving a radio call to the authorities on the ground.

PETERSEN: That's it.

CURWOOD: How well does it work?

PETERSEN: In testing, and we’ve tested the drones by themselves — 1,000 hours and 650 missions flying in places where beforehand, for two years, they had lost 12 to 19 rhinos every month. For the six months that we flew in South Africa, there were no rhinos that were killed. And similarly and independently, we've tested the predictive analytics. In the two weeks that we tested that at a private game reserve, they captured 24 poachers, and, again, there were no animals killed. And so the combination of these two things are a capability that have extraordinary kind of potential, of really just shutting down the poaching where we are able to deploy them.

John Petersen is Chairman of the Charles A. and Anne Morrow Lindbergh Foundation, the organization behind the Air Shepherd program. Professionally, Peterson has been involved with initiatives that incorporate elements of technology, security, and anticipatory thinking and analysis. (Photo: courtesy of Diane Peterson)

CURWOOD: This must be very exciting.

PETERSEN: Well, it's extraordinary, because these animals that we've grown up with, these giant iconic animals, represent an essential aspect of who we are as human beings. And the thought that they would be extinct within eight or 10 years — which is what's going to happen at the present rate if the killing continues — is just psychologically, fundamentally disconcerting. So it is exciting that we have a capability to be able to stop this poaching.

CURWOOD: John Petersen is chairman of the Lindbergh Foundation. His Air Shepard Program is successfully targeting rhino poachers in South Africa. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today!

PETERSEN: Great to be with you, Steve. Thanks so much.

Related links:

- The Charles A. and Anne Morrow Lindbergh Foundation is working to eliminate poaching

- The Air Shepherd Program

- The Peace Parks Foundation

- UAV & Drone Solutions

- Video: technology and intelligence can save animals from poaching

- Graphic video of a rhino with its horn hacked off and left to die

- Ivory DNA analysis pinpoints poaching hot spots in Africa

- ShadowView Foundation supports conservation efforts using unmanned aerial vehicles

[MUSIC: David Kitty, “Ghost World Theme,” Ghost World, Shanachie 2001]

Beyond the Headlines

Brown was the new green at this year’s U.S. Open. The Chambers Bay golf course uses fescue grass, which grows slowly and requires less water than grasses on more iconic golf courses—meaning it’s more drought resistant. Also, Chambers Bay waters the grass with reclaimed water—sewage water from a nearby plant that has been treated to remove solids and impurities. (Photo: Atomic Taco, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Off to Conyers, Georgia, now to find out what Peter Dykstra has to say. Peter’s with the DailyClimate dot org and Environmental Health News — that’s EHN.org — and he’s been checking out what’s notable beyond the headlines. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. I’m not too big on golf. My uncle borrowed my clubs for the weekend in 1978 and hasn’t returned them yet, but I can’t say I’m missing them. But golf and the environment – and all that water it takes to maintain a golf course – are in the news. The U.S. Open was played last week at Chambers Bay, on the shores of Puget Sound in Washington State. The site of the course used to be a gravel mine that was reclaimed as a public park and a world-class golf course. And Chambers Bay uses reclaimed water for its grass, also using sewage sludge from a nearby treatment plant as fertilizer.

For thirty years, electrical companies used polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) to make and insulate devices like transformers and capacitors. Two General Electric plants dumped an estimated 1.3 million pounds of PCBs into the Hudson River before the EPA banned the chemicals in 1977. General Electric has been dredging the river to remove PCBs since 2009, and the project will be completed this year. (Photo: Ryan Varsi, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So the US Open was just partially powered by poop?

DYKSTRA: Sounds like an out-take from “Caddyshack,” doesn’t it? And not all of the golfers liked it. Sergio Garcia, currently ranked as the ninth-best men’s golfer in the world, tweeted a complaint about the brown grass – which is actually a grass variety meant to withstand the brutal drought currently gripping the West Coast. Some golf courses can use up to a million gallons of water a day – including the one in Rancho Mirage, California, where President Obama took some drought-based grief for playing last week – but Chambers Bay hopes to reduce its public water intake to zero within a year or so by using only the reclaimed water from the treatment plant.

CURWOOD: OK, so tee up your next item.

DYKSTRA: A little good news — maybe, kind of. Nearly seventy years after two General Electric factories starting dumping PCBs into the upper Hudson River, the main part of the federally-mandated dredging operation to remove the worst of the contamination is winding down. But EPA says it may take another seventy years – maybe more, and maybe NEVER – for a true recovery of the Hudson. The New York State Department of Health has a daunting “DO NOT EAT” list of fish for the river, including Smallmouth bass, striped bass, walleye, catfish, as well as blue crabs.

Even though 2.7 million tons of contaminated sediment will be removed from the Hudson by the end of 2015, the river still has a long way to go. The EPA estimates that fish from the Hudson won’t be safe to eat for at least seventy years. Ned Sullivan, president of Scenic Hudson, estimates that 40% of the PCBs will remain in the water even after the cleanup project is completed unless more dredging is done. (Photo: Kai Brinker, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So things may be improving for the Hudson, but some pollution, for practical purposes, it seems, is forever.

DYKSTRA: Right, and that also applies to other PCB sites, including New Bedford Harbor and the Housatonic River in Massachusetts, Waukegan Harbor on Lake Michigan in Illinois, and Anniston, Alabama. These chemicals are carcinogenic, and they literally take centuries to break down naturally.

CURWOOD: Huh. Well, on that cheerful note -- take us back for a look at environmental history.

DYKSTRA: We’re coming up on the tenth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina in August, but one of the most important and complete accounts of Katrina’s damage was written thirteen years ago this week, in 2002.

CURWOOD: Wait a second, you’re saying one of the best stories on Katrina was written three years before the storm Katrina?

DYKSTRA: That’s exactly what I’m saying. In June, 2002, reporters Mark Schleifstein and John McQuaid of the New Orleans Times-Picayune launched a series called “Washing Away” – powerful stories about the threats to Louisiana’s coastline and the catastrophic hurricane that would some day engulf the city. These two reporters touched all the bases: how coastal erosion, partly caused by canals and oil pipelines, had eroded much of Louisiana’s hurricane protection. How the levees, including the ones that gave way on August 29, 2005, were no match for a major storm surge. How the state, city and feds were unprepared for a mass evacuation. How a major channel built to give ships a quick exit from the Mississippi River also gave the storm surge a quick entry.

New Orleans Times-Picayune Reporters Mark Schleifstein and John McQuaid predicted the damage done by Hurricane Katrina three years before the storm ravaged New Orleans in August 2005. They anticipated the city’s levees would give way, its channel would facilitate flooding, and its government would be unprepared for a mass evacuation. (Photo: Infrogmation of New Orleans, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And I recall that meteorologists, emergency managers and others had been warning about The Big One for years.

DYKSTRA: Yes, and the stories from Schleifstein and McQuaid tied it all together. They probably saved a lot of lives for those who heeded their warnings about the flood risk and evacuation challenges, but those warnings went largely unheeded by many people in authority. The mayor and governor – both Democrats – and the Republican White House – were bipartisan clueless when Katrina came calling for real. I wish there were a Pulitzer Prize for I-Told-You-So for reporters like these two. More importantly, I wish people would listen more to reporters. And to emergency managers, too. When they wave the red flag, they’re right a lot more often than they’re wrong, and the difference can literally mean life or death.

CURWOOD: Thank you, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Don’t mention it.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, EHN dot org and the DailyClimate dot org – and there’s more on his stories at our website LOE dot.org. Talk to you next time, Peter.

DYKSTRA: OK, Steve, talk to you soon.

Related links:

- US Open played on natural grass

- The U.S. Open grass was brown for a reason

- How California golf courses are staying “green” despite a drought

- EPA guide to PCB risks

- EPA on the Hudson River cleanup

- PCBs persist even with dredging project nearly complete

- ‘Washing Away’ five-part series predicted and warned of Hurricane Katrina and its damages

[MUSIC: Joey Altruda, “Mr.Lucky,” Condo Painting Soundtrack, Gallery Six 1998]

CURWOOD: Coming up: listening to the birds as they change their tunes. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Medeski, Scofield, Martin & Wood, "North London," Juice, Indirecto 2014]

BirdNote®: How Much Birds Sing

Black-headed Grosbeak (Photo: Jerry McFarland)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. If you’re an early riser or have trouble sleeping, you’ll notice that some birds are already singing fit to beat the band in the dark hours before dawn — which, around now, close to the summer solstice, can be very early indeed in parts of the country. But as Michael Stein explains in today’s BirdNote®, many different factors affect when and how much birds actually sing.

[MUX - BIRDNOTE® THEME]

BIRDNOTE®/HOW MUCH BIRDS SING

[Black-headed Grosbeak song]

This rollicking song belongs to a Black-headed Grosbeak. [Black-headed Grosbeak song] Like most birds, the male grosbeak begins singing in earnest a few days after reaching his traditional nesting grounds in spring. [Black-headed Grosbeak song] And, like most birds, he sings frequently when trying to attract a mate. He’ll sing a bit less while he and his mate incubate eggs, but pick up the pace again after the young hatch. [Black-headed Grosbeak song] By late summer, his singing will cease.

Ever wonder how much a bird sings in one day? Some patient observers have shown that a typical songbird belts out its song between 1,000 and 2,500 times per day. Even though most bird songs last only a few seconds, that’s a lot of warbling!

Sage Thrasher (Photo: Bob Devlin)

On nights with a full moon, male Sage Thrashers have been known to proclaim

their long-winded songs all night. [Sage Thrasher song] But the North American record-holder may well be the Red-eyed Vireo. One such vireo delivered its short song over 22,000 times in ten hours! [Red-eyed Vireo song]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Song of the Black-headed Grosbeak 126546 recorded by T.G. Sander; song of Sage Thrasher 120223 recorded by G.A. Keller; song of the Red-eyed Vireo 110208 recorded by W.L. Hershberger.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2015 Tune In to Nature.org June 2015 Narrator: Michael Stein

Images:

Black-headed Grosbeak © Jerry McFarland https://www.flickr.com/photos/56509109@N04/18103573032

Sage Thrasher © Bob Devlin http://www.njaudubon.org/SectionCenters/SectionSHBO/SandyHookRarities.aspx

Red-eyed Vireo © Kenneth Cole Schneider https://www.flickr.com/photos/rosyfinch/5014856909

http://birdnote.org/show/how-much-birds-sing

Red-eyed Vireo (Photo: Kenneth Cole Schneider)

CURWOOD: You can find photos of some of these champion songsters at our website, LOE.org.

[BIRDSONG]

Related links:

- BirdNote®’s “How Much Birds Sing”

- Red-eyed Vireo: photos and more about the species

- More stories about the Black-headed Grosbeak on BirdNote®

The Evolution of Birdsong

Black-capped Chickadee (Photo: Macaulay Library, Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

CURWOOD: While strolling in the woods, you’ll likely hear the chatter of a lively bird community — some tweeting a note or two, while others go on for minutes at a time — each communicating a message, like humans. In fact, many scientists believe that speech in humans evolved much like birds. We share similar brain structures and genes associated with speech, and our language systems are even similar.

And just as environmental pollutants and climate change are altering human life, they also affect bird life — in this case, their songs, from individual birds and species to entire habitat soundscapes.

Michael Webster is the Director of the Macaulay Library at The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and he joins us to explain how environmental changes are shaping the evolution of birdsong. Welcome to Living on Earth.

WEBSTER: Glad to be here.

Starling (Photo: Macaulay Library, Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

CURWOOD: So I need the basics here. Please describe the components of birdsong. In what ways are birdsongs similar to, and in what ways are they different from, human language?

WEBSTER: Birdsong is actually very similar to our own communication, our own way of speaking to each other. They have notes or phrases which are basically the equivalent of our words and then they string those notes and phrases together in combinations that have sort of a syntactical organization to them, so that would be the same as our sentences. Likewise, many birds learn their song. They have a critical period early in life, where they're very sensitive to what they're learning and are able to learn those, incorporate those, much later in life when they've had a chance to practice.

CURWOOD: Now, when you evaluate changes in birdsong, what kinds of factors do you have to consider?

WEBSTER: Birdsong -- it’s a communication system, and with any communication system you have basically three components: there is the signaler, or the individual that is making the signal; there is the receiver at the other end who is receiving the signal; and in between them is the environment. And the signal has to transmit through that environment, and so all three of those components can be affected by things like human activities, by the biological community, by climate change.

The world is becoming a very noisy place, and all of that throb of humanity, if you will, that we're generating is something that animals need to deal with and communicate around or through, in ways that they can still be heard and understood by the other birds out there. And we're starting to see these changes now. So, for example, birds in urban areas are singing somewhat differently than birds in more rural areas, because there's that low-frequency human noise masking the low frequencies birdsongs that they would make. To deal with that, they've had to shift their songs upward in pitch.

CURWOOD: Now, how might elevation change birdsong?

WEBSTER: A lot of things change with elevation. As you go up a mountain side, the air gets thinner, the vegetation changes, the temperature changes. Any of those things can affect how song transmits through the environment. There has been some very interesting work done recently to look at how song varies with elevation. So, for example, Mountain Chickadees in the Sierra Nevada mountains in California, it turns out that different populations have different songs. And that's not too surprising if you go from one mountain top to another mountain top; the birds probably don't disperse much between mountain tops. But what was surprising is if you go higher in elevation on the exact same mountain, the birds low down on the mountain sing different songs than the birds higher up on the mountain. And the reason for that is probably that they tend to stay in the same region or the same elevation as where they grew up, because they're most adapted to that elevation, and that's causing these regional dialects. You have birds lower down in the mountain sounding different from birds on top.

CURWOOD: Please play an example.

Mountain Chickadee (Photo: Macaulay Library, Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

WEBSTER: Sure, this is a Mountain Chickadee from the Sierra Nevada.

[SFX: MOUNTAIN CHICKADEE]

WEBSTER: And here's the same species, a Mountain Chickadee from another population.

[SFX: HIGHER PITCHED MOUNTAIN CHICKADEE]

CURWOOD: Yeah, that is different. So many birds migrate or the range of nonmigrating birds is also changing. How much that affect their songs?

WEBSTER: I actually think this is one of the biggest consequences of climate change for birds. What we know already is that the ranges of birds are changing around us. Birds are moving northward, they're moving southward, they're moving to expand the range and areas where they didn't previously exist. The consequence of that is we have a lot of species that are coming together in areas that didn't really coevolve with each other, and didn't really coexist with each other previously. What that means is the entire soundscape, the environmental noise that surround the bird, is different now than it was a few generations ago.

These songs that the birds sing to each other and use to communicate with each other are adapted to fill up the sort of acoustic niche space, if you will. So the different sounds, different species have partitioned off different sections of that space, and if you had different species coming together that didn't coexist before, that means that the acoustic space is becoming jammed, and the birds songs are overlapping with each other in ways that they never did before. And that can cause all sorts of interference, it might lead to birds evolving to sing in different parts of that niche space so they can still communicate with each other — just like when they have to live in an environment with humans, where we're filling up their acoustic space with our own sounds.

Song Sparrow (Photo: Macaulay Library, Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

CURWOOD: Of course, in some locations we have pollution to deal with as well. I understand that chemicals such as DDT and PCBs have been known to alter birdsong. How do some of these affect birdsong?

WEBSTER: Well, that's right. We've known for years that a lot of these chemicals like DDT can affect mortality and death of birds. What we're now starting to understand is that there are far more subtle effects of these pollutants on the lives of birds and the ways that they interact and communicate with each other.

So, for example, PCBs work their way through the food web through the insects, and the parent birds feed those insects with the PCBs in them to the young nestlings. And we have discovered that these PCBs affect the development of the song areas in the brain, so that when they grow up, they don't seem to be able to sing as well as birds that are not exposed to these same contaminants. There's been some really nice work done on Chickadees showing exactly that.

CURWOOD: Let me hear the Chickadee that has been exposed.

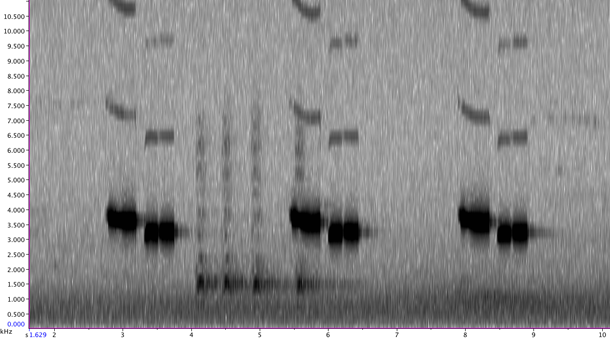

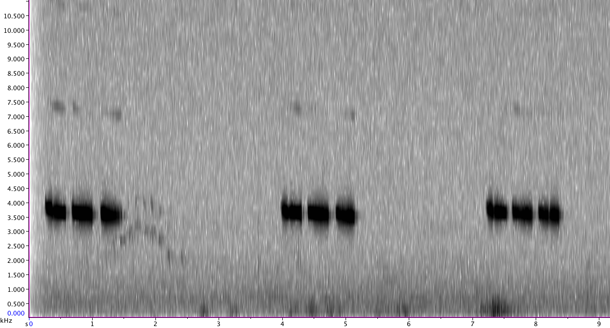

[SONG: CHICKADEE]

WEBSTER: What we're listening to here is a Chickadee that has been exposed from the Hudson Valley. And this is an area with high levels of PCB and the songs of birds that grow up in this area are less consistent and therefore lower quality than males who grow up in other areas. Conversely, at the other end of the spectrum, song sparrows seem to actually sing a better song when they've been exposed to the poison. They have a longer trill and a more consistent trill, which is something the females seem to pay attention to.

[SONG SPARROW]

CURWOOD: Now, there's some pollutants like Bisphenol A that change birdsong as well, I understand. Please tell us how this has affected Starlings.

Spectrogram of a Black-capped Chickadee from New York State. (Photo: Macaulay Library, Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

WEBSTER: Yes, so Bisphenol A is an estrogen mimic, and in Starlings it has been shown to affect the development of the song centers. But, in this case, the Starlings who are exposed to that contaminant ,again, sing more complex and, if you will, sexy songs that the females seem to like better.

[STARLING CHORUS]

WEBSTER: But in a way, the males are completely messed up because Bisphenol A also affects their immune system, so the females are actually being attracted to the less fit or the lower quality males, which is more or less exactly the opposite of what these songs originally evolved to do. The songs are supposed to be convincing information about male quality so the females are attracted to the highest-quality males, not the lowest quality males.

CURWOOD: How well can we humans distinguish these changes in birdsong?

WEBSTER: It's pretty challenging for us to distinguish these differences because we're listening with human ears, and the human ear is quite different from the bird's ear. Birds are much better at distinguishing subtle frequency and temporal differences in song that we can't pick up very well.

The way that we do the research and we understand the changes that are occurring in the birdsongs is by generating spectrograms, so turning the song itself into a visual representation of the song — essentially a graph that we can use to actually measure things like pitch, and the duration of notes, and how the change in note pitch changes over time, and quantify those things and use that to understand these subtle differences in the birdsongs that we can't actually hear with our own ears.

Spectrogram of a Mountain Chickadee’s whistled song from the Rocky Mountains in Wyoming. (Photo: Macaulay Library, Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

CURWOOD: So, overall, many factors play into how birdsong involved; but considering the effects of climate disruption and pollution, how do you see things going?

WEBSTER: Very hard to predict. We've all seen the projections for climate change over the next several decades. We know that the birds are going to be living in a very different world than they have been living and a very different world from that that they evolved in. And that will affect the way they communicate with each other just as other aspects of their life — what they eat, where they live, things like that. What I do know and can say with some confidence is that there will be far more subtle effects of climate change on these birds, and how they communicate with each other, than we have been appreciating in the past. The positive is that birds have dealt with climate change in the past, they've existed through glacial ice ages, and they've evolved to deal with those changes. So what we will see over the next several decades is how birds contend with and evolve to deal with an ever-changing world.

CURWOOD: Michael Webster is the Director of the Macauley Library at the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. Thanks for taking the time with us today.

WEBSTER: Thank you, it was a pleasure.

Related links:

- Pollutants cause birds to sing tainted love songs

- Bird 'accents' change with elevation

- Climate Influences Language Evolution

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library

[MUSIC: The Beatles, “Blackbird/Yesterday,” Love, (Cirque du Soleil), Capitol 2006]

Purple Martins: Extroverts of the Air

The purple martins can’t seem to stop talking. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: East of the Mississippi, Purple Martins are completely dependent on the nest boxes we build for them. Perhaps that’s why they are exceptionally tolerant of human beings. Though, at times, when writer Mark Seth Lender listened to them, he wasn’t sure that what they were saying entirely expressed their approval.

Conversational: Purple Martins

© 2015 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

LENDER: Looping, they land. A fist-full of sapphires: Purple Martin (blue, on black). They stand, at the doorways of their houses made of tin, walls ringing at their touch. Their loud purple tinted talk. The clip! of flight feathers as they climb again into the sky. In curves and curls, sideways pointing, inside, upside down: Purple Martin hunting insects on the wing. Follow the figure if you can, a course no kite tethered to a human hand can shadow. They clatter as they fly. Too much to say, too little time. Mouths wide as the blue horizon, a long bright glittering. Over the cloud-filled pond. Over the dark green land.

In between snippets of conversation, purple martins on the wing snatch dragonflies from the air – then go right back to their chattering. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

And again to their perch all-at-once, talk-talk-talking.

One goes where he should not, a station that belongs to someone else, and voices rise and feathers fray and feet tangle in midair! One offended. One chastised. One self-righteous and victorious. One, inglorious. Then each back to their rightful place, and the chorus of conversation drops back to the conversational.

I’ve come to listen and to watch, out in the open, close in. They circle, then, wings wide, they glide, and grasping to the landing place they settle — But not quite not all the way. They keep me in sight, every one. And the chatter becomes a stage whisper below the normal pitch of Purple Martin talk. Whirr. Purr. Hum. The staccato of their clicks like punctuation marks (as well these may be). Overtones…. Harmonies…. The cantillation of some ancient text, no doubt, we once understood. Lost to us now a thousand centuries.

Wingtips flared, a purple martin glides deftly onto its home. Menunkatuck Audubon Society maintains the purple martin houses at Hammonasset State Park in Connecticut. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

The sun goes down. The day comes to a stop.

[CHORUS OF CHATTERING PURPLE MARTINS]

In the last of twilight Purple Martins go on talking, as if behind my back. To each other? To themselves? All about . . . Me?

CURWOOD: Writer Mark Seth Lender recorded these purple martins at Hammonasset State Park in Connecticut, where their nest boxes are maintained by the Menunkatuck Audubon Society. There are photos at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- About the Menunkatuck Audubon Society

- About purple martins

- Attracting purple martins to your backyard

[MUSIC: Mychael and Jeff Danna, “The Blood of CuChulainn,” A Celtic Romance, 1998]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth: water from glaciers is the key to hydropower in the Pacific Northwest.

RIEDEL: Having glaciers provides stability to our water supply. So you get into mid-late July and that snow is melted out of the mountains. If it weren’t for glaciers our stream flow would drop pretty dramatically.

CURWOOD: But the glaciers are retreating fast. That’s next time on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Shannon Kelleher, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, James Curwood, and Jennifer Marquis. Our show was engineered by Tom Tiger, with help from Jake Rego, Noel Flatt and Jeff Wade. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth