September 7, 2012

Air Date: September 7, 2012

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Obama Environmental Policy for a Second Term

/ Steve CurwoodView the page for this story

President Obama seeks a second term in office, with the energy achievements of the last four years front and center but Rebecca Noblin from the Center for Biological Diversity, tells host Steve Curwood that some of the President’s decisions on the environment are based on politics instead of science. (06:30)

Arctic Summit

/ Steve CurwoodView the page for this story

The melting Arctic sea ice has opened a passage to Iceland for a Chinese ice-breaker. Iceland's President, Ólafur Grímsson, tells host Steve Curwood why Chinese scientists see the disappearing ice as a threat as well as an opportunity. (07:30)

Science Note- Rainbow Trout

/ Annabelle FordView the page for this story

Scientists have located a magnetic cell in rainbow trout that is believed to guide fish and other species during migration. Annabelle Ford reports. (02:10)

Cracking the Code for Monsoons

/ Murali KrishnanView the page for this story

Indian Scientists are collaborating with collegues in the US and UK to develop new computer models to predict the movements of monsoons. Radio Deutsche Welle's Murali Krishnan reports that such information that will be critical for the millions of Indians who depend on farming for their livelihoods. (06:00)

Global Weirdness

/ Steve CurwoodView the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood talks to author Michael Lemonick about his new book that explains in simple and straightforward terms the basic science of climate change. (06:50)

Great Blue Heron

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Beaver ponds provide the perfect habitat for Great Blue Herons. The birds make their nests in trees that drowned after beavers dammed streams. Mark Seth Lender reports. (03:10)

Spinach Power

/ Steve CurwoodView the page for this story

Scientists at Vanderbilt University have found an exciting new use for spinach, harnessing energy from the sun. Kane Jennings, a Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, tells host Steve Curwood that using a protein found in Spinach can create a highly productive solar cell. (05:15)

Bagging Big Trees

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Every year the non-profit American Forests updates their registry of the biggest trees of each species in the country. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb learns how to measure champion trees. (09:35)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Rebecca Noblin, Olafur Grimsson, Michael Lemonick, Kane Jennings,

REPORTERS: Annabelle Ford, Murali Krishnan, Mark Seth Lender, Bobby Bascomb

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International—this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

Less than two months till election day—and President Obama reckons he has successes to run on - including a strong environmental and energy policy.

OBAMA: And yes, my plan will continue to reduce the carbon pollution that is heating our planet—because climate change is not a hoax. More droughts and floods and wildfires are not a joke. They're a threat to our children's future. And in this election, you can do something about it +applause. :16

Also—in a world of increasingly capricous weather, scientists turn to supercomputers to better forecast India's unpredictable monsoon…

BASU: India feeds 17 per cent of the world's population with its 1.2 billion population with just 4.3 of the water that the world gets.

CURWOOD: President Obama and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick Around!

[THEME]

Obama Environmental Policy for a Second Term

(Associated Press)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

OBAMA: Madam Chairwoman, delegates, I accept your nomination for president of the United States.

President Obama's speech at the end of the Democratic Party Convention was sober and inclusive—with a rigorous defense of his first term record.

OBAMA: After 30 years of inaction, we raised fuel standards so that by the middle of the next decade, cars and trucks will go twice as far on a gallon of gas. We have doubled our use of renewable energy, and thousands of Americans have jobs today building wind turbines and long-lasting batteries. In the last year alone, we cut oil imports by 1 million barrels a day—more than any administration in recent history. And today, the United States of America is less dependent on foreign oil than at any time in nearly two decades.

(Applause)

CURWOOD: The President reminded America of the clear distinction between his energy and environmental policies and those of the Republicans.

OBAMA: So now you have a choice—between a strategy that reverses this progress, or one that builds on it. We've opened millions of new acres for oil and gas exploration in the last three years, and we'll open more. But unlike my opponent, I will not let oil companies write this country's energy plan, or endanger our coastlines, or collect another $4 billion in corporate welfare from our taxpayers.

We're offering a better path. We’re offering a better path—a future where we keep investing in wind and solar and clean coal; where farmers and scientists harness new biofuels to power our cars and trucks; where construction workers build homes and factories that waste less energy; where we develop a hundred year supply of natural gas that's right beneath our feet. If you choose this path, we can cut our oil imports in half by 2020 and support more than 600,000 new jobs in natural gas alone.

And yes, my plan will continue to reduce the carbon pollution that is heating our planet— because climate change is not a hoax. More droughts and floods and wildfires are not a joke. They are a threat to our children's future. And in this election, you can do something about it. + applause.

CURWOOD: Well, Obama's energy strategy may reduce the need to import oil, but a number of scientists and environmental advocates worry about the risks of some of those energy sources. And they question plans to drill in sensitive ecosystems like the Alaskan Arctic waters.

The White House recently gave Shell Oil the green light to begin exploratory drilling in the Chukchi Sea. Rebecca Noblin is the Alaska Director at the Center for Biological

Diversity.

The Chukchi Sea separates

NOBLIN: The big thing that Shell wants to be doing is drilling in the hydro-carbon zones, and they haven't gotten the go ahead for that yet. But there are risks to the initial drilling that shell has already been allowed to do.

CURWOOD: So, Shell can’t drill down to the hydrocarbon or the oil zone until what, some oil containment barge reaches this area? As I understand it, that vessel is currently held up in Washington State. Why do they need that vessel and what’s the holdup?

NOBLIN: Shell is required to have its oil spill containment barge, the Arctic Challenger, onsite when it drills into hydrocarbon zones. And, basically, this containment barge is supposed to be a backup system in case there’s an oil spill, its new technology to deal with an oil spill. Shell just has not been able to get its act together; the Arctic Challenger has been challenged! It can’t get its permits from the Coast Guard, and, without it, Shell can’t meet its oil spill permit requirements.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, this containment vessel was supposed to be good for a 100-year storm. What are the rules that the Coast Guard and the Obama Administration are saying now about it?

NOBLIN: Yeah, so another one of the many broken promises from Shell is that this barge would meet the 100-year storm requirement. Earlier this summer, Shell announced that it wasn’t going to be able to do that, and it asked to be able to meet a ten-year storm requirement. And the Coast Guard went ahead and allowed that.

So now, the containment barge only has to meet the ten-year storm requirement, which is really kind of a bad idea. We’re seeing, with climate change, a lot of big storms. So, 100-year storms are more likely to come a lot more often than every 100 years, these days. But, anyway, the Obama Administration did allow Shell to have that weaker standard. Nevertheless, Shell still can’t get that containment barge up and running.

CURWOOD: Now, there’s also some controversy about Shell meeting the Clean Air Act requirement for this operation, and the Obama Administration has given them a break on that… could you explain?

NOBLIN: Yeah. This summer, Shell announced that, again, it could not meet its Clean Air Act permit requirements, and it asked for a waiver from the Obama Administration, from the EPA. Basically Shell plans to emit three times the amount of nitrogen oxide that it was originally permitted to emit, and ten times the amount of particulate matter. So, it’s a pretty significant increase in pollution.

And the only way to get a new permit would be for the EPA to go through a whole new public process, which would have prevented Shell from drilling this summer. So instead, Shell asked for and the EPA just last week granted a waiver of its air permit that required no public process. The EPA simply said OK you don’t have meet those requirements for the next year while we work on a new permit.

CURWOOD: Rebecca Noblin, what’s your take on the politics of Shell getting permission to go ahead with the drilling right now?

NOBLIN: It’s clearly a political decision on the Obama Administration’s part to allow Shell to move forward with drilling. It’s not a science-based decision, it’s not a precautionary decision. The Obama Administration has really bent over backwards to show that it’s pro drilling. And, it seems that the Arctic has really become the next sacrifice zone after the Gulf of Mexico.

CURWOOD: Rebecca Noblin is Alaska Director for the Center for Biological Diversity speaking to us from Anchorage. Thank so much!

NOBLIN: Thank you.

Related link:

Transcript of President Obama's Speech

Arctic Summit

The Arctic Ocean near Barrow, Alaska. (Arctic Imperative Summit)

CURWOOD: Environmental activists aren’t the only ones to see threats from fossil fuels in the Arctic; world leaders see threats as well as opportunities. A warming climate means that sea ice in the far north is melting faster than ever expected.

That was one of the topics under discussion at a recent summit, the Arctic Imperative summit in Alaska. The President of Iceland, Olafur Grimsson gave the keynote speech -

Welcome to Living on Earth, President Grimsson.

GRIMSSON: Good day, very nice to speak to you.

CURWOOD: So you're at the Arctic Summit there—you've been at the Arctic Summit there near Anchorage Alaska—who was there and why has this meeting been important?

GRIMSSON: So at this conference we have great participation from Alaska—people from public life, from the indigenous communities, of the local communities as well as from the corporate world, plus people from the Canadian and the American forces, and I think all of this confirms the growing importance of the arctic.

CURWOOD: Let me ask you about a recent visit you had in Iceland from the Chinese icebreaker the Snow Dragon. As I understand it this is the first time that the Chinese have been able to send an icebreaker up through what is called by some the northwest passage—others the northeast passage—what was the significance of that trip?

President of Iceland Olafur Ragnar Grimsson gave the keynote address at the Arctic Imperative Summit. (Arctic Imperative Summit)

GRIMSSON: The opening up of the new sea routes which you mentioned, the northeast sea route which would in fact shorten the distance between China and Europe and China and the United States by about 40 percent, but the arrival of the Xuelong in Iceland also confirmed the interest of Chinese scientific community in the arctic. There were about 60 Chinese scientists from the Chinese Polar Institute. They explained how the melting of the ice in the arctic has a profound impact on the weather patterns in China, and on the agriculture, on the food production, the well being of the people in the city.

CURWOOD: What of those effects, of the changes in the arctic, on China, made the biggest impression on you? What’s a particular detail that caught your attention?

GRIMSSON: Well, if the Greenland ice sheet and the ice in Antarctica keeps on melting, this would raise sea levels to a certain extent that the seashore would move 400km inwards in China, and this would drown cities like Shanghai. It would make Beijing surrounded by seawater, and it was quite a dramatic presentation of the effect of climate change.

CURWOOD: These scientists obviously impressed you. What effects do you think they’re having at home, on their own policies? They’re still using a lot of coal, they’re still putting a lot of carbon into the atmosphere.

GRIMSSON: Well, of course they have an effect on that, but, let’s remember China is now already the leading producer and user of wind energy, of solar energy, and a few months ago, during the visit of the Prime Minister of China Wen Jiabao to Iceland, we signed an agreement for transforming the urban heating system in many Chinese cities, from coal to local, clean, geothermal resources—to do in China what we have done in Iceland.

So I think all of this is combined in a comprehensive view, which will make China, I believe, before the end of this decade, the leading clean energy country in the world. I know that sounds paradoxical to American ears, but I believe, based on these facts, that unless Europe and the United States get their act together in the field of clean energy, the question before the end of this decade will be: when will Europe and when will the US catch up with China in the field of clean energy?

CURWOOD: By the way, as I understand it, Iceland is carbon neutral?

GRIMSSON: We are 100 percent clean energy in terms of all electricity production and all space heating. And if we succeed in getting electric cars and all of the clean energy cars in the next five to ten years, we could become the first country where all land-based activity derives its strength from clean-energy sources.

And I think the story about Iceland is that it can be done. Because when I was young, over 80 percent of our energy came from imported oil and coal. So within the lifetime of one generation, we have moved from oil and coal over to clean energy. Just to give you an indication of the economic benefit of this, by moving from imported oil to heat our houses to local geothermal resources, we save every decade what amounts to one year’s gross national product.

CURWOOD: Wow. Wow, that’s impressive. Now, with ice coming out of the arctic, there’s a lot more drilling for hydrocarbons going on there—what threats to do you see from more drilling in the Arctic?

GRIMSSON: Well, I think everybody who studies drilling in the arctic is very much aware of how careful people have to be. And I think what is being planned here in Alaska and what is being done by Russia and Norway and other countries in the arctic in this respect, is based on a very strong scientific and environmental analysis. Because those who live close to the ice and off the ice—they are very much aware of what the risks are and how profoundly strong the weather patterns can become.

CURWOOD: I mean, how much sense does it make to be drilling for more hydrocarbons, when they are the problem with melting the Arctic?

GRIMSSON: Well, that is of course a very good question. But the problem is that for most people in the United States, in India, China, Europe, Latin America… for our everyday life, we require this fuel. So until other countries go the way of Iceland, reducing their reliance on this, there will be growing demand.

CURWOOD: Overall, how bad are things looking for the Arctic, for the ice regions of the world, from your perspective… from where you see, sitting as President of Iceland?

GRIMSSON: Well, first of all, all nations live in an ice-dependant world. What happens to the ice in the arctic, in the Himalayas, and in Antarctica will have a profound effect on every nation, on every continent. And the melting of the ice in the last four years has been much more dramatic than anybody predicted ten years ago. And therefore, we need all to be gravely concerned about the effect and the impact of this for everybody on planet earth. That is why the Chinese icebreaker was in Iceland, because of how afraid they are that the melting of the ice in the Arctic will prevent economic and social development and progress for the people of China in the coming decades. And if the Chinese are now scared and afraid, we who live in Arctic, and America's an arctic state through Alaska, should be as concerned.

CURWOOD: Olafur Grimsson is President of Iceland, thank you so much, sir.

GRIMSSON: Well, thank you very much, thank you.

Related link:

Arctic Imperative Summit

[MUSIC: Jazz Soul Seven “We’re A Winner” from Impressions Of Curtis Mayfield (BFM Jazz 2012)]

CURWOOD: Just ahead—super-computers take on the task of tracking the wayward Indian monsoon—stay tuned to Living on Earth!

CUTAWAY MUSIC :Antibala: Dirty Money” from Antibalas (Daptone records 2012)]

Science Note- Rainbow Trout

Caption: Cells containing magnetite, the most magnetic mineral on earth, have been located in the rainbow trout’s olfactory region. (Latham Jenkins/Circumerro Stock, Creative Commons, Flickr)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Coming up—a new book that tries to explain the weirdness of the global climate, but first this Note on Emerging Science from Annabelle Ford.

[MUSIC/MOVIE CLIP FROM FINDING NEMO "Just Keep Swimming"]

FORD: In the movie Finding Nemo, a clown fish ‘just keeps swimming’ for hundreds of miles in search of his lost son. In the real world, many migratory fish and birds travel similar distances to return to their birthplace. And while they don’t have a little blue fish called Dory to encourage them, they do have a tiny helper that enables them to navigate their way home.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

FORD: The migratory species’ helper is a cell that contains magnetite, the most magnetic mineral on Earth. Scientists have long accepted that migratory species are sensitive to the Earth’s magnetic poles, but this is the first time that the precise cell with this magneto-sensitivity has been located.

A research team at Munich’s Ludwig Maximilians University studied rainbow trout and placed cells from their olfactory tissue under a microscope. A magnet under the microscope’s stage was rotated beneath the sample and the team was able to isolate several cells that moved with the magnet.

The cells that moved were then individually studied and found to contain magnetite, as expected. What makes this finding particularly interesting is the cells’ scarcity: only about one in 10,000 cells in the fish’s nasal tissue contains magnetite. And it turns out the scientists have not only located the cell, but they’ve also discovered its magnetic sensitivity is stronger than suspected.

The team estimates that the cell is up to 100 times more receptive to the pull of the magnetic poles than previously thought. They believe that rainbow trout may be able to perceive not just which way is North, but to sense their longitude and latitude as well.

The next step is to figure out if these few cells located in the fish’s nose are actually sensory cells that link to the brain. Scientists will have to ‘just keep researching’ before they know for sure. That’s this week’s note on emerging science, I’m Annabelle Ford.

Related links:

- An article on the discovery

- The report published by the research team

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Cracking the Code for Monsoons

CURWOOD: Over half of people in India depend for their livelihood on farming, a job that's both tough and economically insecure. Less than half of Indian farmland is irrigated, so the annual monsoon is crucial. And this year, the monsoon came late, and has been sparse in much of the northern agricultural belt, leaving cracked fields and stunted crops.

But Indian scientists have teamed up with colleagues from the US and the UK to build new computer models to help predict the movements of erratic monsoons in advance. Super-computers, they say, will allow them to crack the monsoon source code. From New Delhi, Radio Deutsche Welle's Murali Krishnan has our story.

KRISHNAN: Debashish Sarkar, a small-time farmer, looks forlorn as he surveys his three acres of mustard and rice fields. Every now and then he looks up to the skies, hoping they will open up, as without the much-needed rains, he knows his crop will almost certainly fail. Small landowners like Sarkar are totally dependent on the monsoons to sow their fields. Erratic monsoons can put their lives in jeopardy.

SAKAR (THROUGH TRANSLATOR): Even this year, it looks as if there are going to be no rains. Until July, the rains have been scarce. This time too, the villagers are bound to suffer. All my fields are going to be destroyed… it's a major loss.

KRISHNAN: To address the problem, India's Institute of Tropical Meteorology, based in the western city of Pune, is working on a multi-million dollar National Monsoon Mission. The project aims to forecast extreme climate events, such as drought and floods, active and dry spells of monsoon, and more importantly, collect data on how rain will fall across the country.

If successful, it could drastically improve the economic prospects of about 600 million people in India, whose lives depend directly on the agricultural sector. Dr. M Rajeevan, an advisor to the Ministry of Earth Sciences is overseeing the project.

RAJEEVAN: The farming community needs longer forecasts than the medium range. That means forecasts from seven days to a range of one month. These forecasts aren’t being generated at the moment, but we expect that with this monsoon mission, we will do a better job.

KRISHNAN: The national Monsoon Mission has started using a dynamic model of prediction, which was developed by the US-based National Centers for Environmental Prediction. The dynamic model involves using super-computers to compare land and sea surface temperature data, wind speeds, and air pressure from the past 50 years to predict the monsoons.

Up until now, the Indian Meteorological Department (or IMD) has used a statistical model. S. C. Bhan, the IMD's deputy director general, says statistical analysis is still accurate for long-range forecasts.

BHAN: The focus beyond medium time-scales will be better, and the farmers will be able to make use of this information in terms of planning the seasonal aspects of their different crops: what to sow, when to sow, how much proportion and percentage of different crops. And also in the medium time scales, for making tactical decisions about when to irrigate, how much to irrigate and whether some pesticides and fertilizers are to be applied or not. That will help them bring down the cost of cultivation to a greater extent.

KRISHNAN: But the new model will benefit the country’s agricultural class in the short-to-medium term. The move is being closely watched by the agricultural sector; after all, it employs half of the country’s workforce. P.K. Basu, India’s former Agriculture Secretary, who retired a few months ago, says it’s critical.

Commerce carries on during the monsoons. (Photo: fbloeink)

BASU: I think it is very critical; extremely critical for two or three reasons. One is, that India feeds 17 percent of the world’s population with its 1.2 billion population, with just 4.3 [percent] of the water that the world gets. So, we have a huge task on our hands, and any mistake that we make on the monsoons is extremely costly – as we have seen in the past in 2002, and 2009. And any improvement in the forecasting and prediction would be a great help in stabilizing food production in the country.

KRISHNAN: But these are early days. A lot will depend on how the government utilizes the new data. While it will be an advantage to know when the rains will fall, the government will also have to ensure that farmers get the right crop varieties, and that, on time. P.K. Basu again.

BASU: Where we are still deficient is the time period of about, say, 10-15 days. If somehow this mission can give us that kind of information 15 days ahead, it will help the farmers plan sowing…plan other agricultural activities very well. And I believe it is going on track, and I was assured by the IMD, that, and the Earth Science Ministry, that they are working on this problem very seriously.

KRISHNAN: In the past 130 years, the IMD has never been able to forecast a drought. Not in 1987, 2002, 2004, or 2009. Each time it predicted normal or near normal rainfall. In the past 12 years, the closest the IMD has come to a correct forecast was in 2005 when it predicted 98 percent rainfall and the actual level was 98.8 percent.

DW Radio Spectrum

It’s worst prediction was in 2002, when it forecast 101 percent rainfall, and the country only received 79.4 percent. So do farmers like Sakar have faith in this new national monsoon mission?

SAKAR (THROUGH A TRANSLATOR): Who knows what next year brings? Let's at least hope we have good rains.

KRISNAN: This year, the government has banked on a normal monsoon to boost weak economic growth. But so far, the reality has once again fallen short of everyone’s expectations. This is Murali Krishnan, in New Delhi.

CURWOOD: Our story on tracking the monsoon in India comes to us by way of the Radio Deutsche Welle science show: Spectrum. Now this year's sparse and spotty monsoon in India is not the only example of weather behaving unpredictably.

Global Weirdness

CURWOOD: Here in the US, it was the winter that mostly wasn't this year. Then record heat has brought record wildfires, and sea ice in the arctic is reduced to historic low levels. You could be forgiven for thinking the weather is weird—and a timely book arrived in our office, called “Global Weirdness: Severe Storms, Deadly Heat Waves, Relentless Drought, Rising Seas, and the Weather of the Future.”

It comes from Climate Central, a non-profit journalism and research organization, and its 60 short chapters seek to explain in simple, straightforward terms the basics behind the Earth and its changing climate. Michael Lemonick is its co-author.

LEMONICK: Well the book is aimed at the people who really don’t understand climate change all that well—they hear competing stories from people who are advocates for doing something about it and skeptics, and it’s a lot of information that’s just very confusing. We are hoping to reach those people with a very simple, straightforward explanation of why people are concerned about climate change… just to give them a basis for making good decisions for themselves.

CURWOOD: Global warming 101?

We spoke with co-author Michael Lemonick about his new book, Global Weirdness. (Photo courtesy of Michael D. Lemonick)

LEMONICK: Global warming 101 with a special twist, I think, in at least some of the chapters, where we take a number of the arguments that skeptics make—the counterarguments to human-triggered climate change—and we address them in a kind of respectful way, because at their base, these questions are very reasonable; the idea that ‘how do we know it isn’t the sun that’s warming the earth, how do we know this isn’t just a natural climate cycle?’

So ordinary people that I run into are still asking those questions, and so we try and respect their common sense, and say, ‘yeah, you’re absolutely right, it makes sense that it would be the sun. Here’s why we know that it isn’t.’

CURWOOD: So what then do you hope people will take away from your acknowledgement in this book that we can’t say for sure exactly what will happen—doesn’t that feed skepticism?

LEMONICK: Well I don’t think it does, because we do admit that we don’t know exactly what will happen to sea level rise or exactly how high temperatures are going to go by 2100, but we are very clear about the fact that the vast, vast majority of people who actually study this topic agree that it is going up, and that the consequences are quite likely to be dangerous and harmful to people, and property, and ecosystems. So we just admit that it’s a real threat whose exact parameters we don’t yet know, and that there is still research going on.

CURWOOD: How long ago did you start this project?

LEMONICK: We started it about two years ago.

CURWOOD: So did you have any idea that when the book came out you’d be seeing record tornadoes, record drought, some pretty difficult heat waves, some crazy storms?

LEMONICK: Yeah, we actually planned it exactly for that. And you know, I hope, that I’m completely kidding, because there’s no way we could have known. But, you know, if you read the book, you will learn that these events are going to be on the increase generally, as the years and the century goes by. And so, it’s not surprising that there are extreme events to point to, right at the time the book comes out.

CURWOOD: In fact, in your book you use the year 2100 as a benchmark for folks, and some raise the question that the lack of immediate or tangible gratification is a big challenge to convince people to adopt an eco-friendly behavior by having such an out-year target for when things get really difficult. What’s your response?

LEMONICK: Well the response is that we can point to events, like the extreme weather you just talked about, that are happening now. We can point to the fact that spring is coming two weeks earlier on average in the U.S. and that it’s actually very disruptive to ecosystems. We can point to the fact that sea level is already eight inches higher than it was in 1880, and that when combined with the storm surges, the flooding that results is already dangerous.

We can point to the streams that are running drier earlier in the summer, with negative effects as far as wildfires are concerned and also agriculture and even drinking water supplies. So there’s enough going on already to make it clear that these really serious effects that we’re gonna see by 2100 are already affecting our lives.

CURWOOD: Now towards the end of your book, you have several essays about possible solutions: Can nuclear power help? What about futurist technology? But these chapters all seem to conclude that…mmm...we’re in pretty tough shape.

LEMONICK: Yeah, I mean I really, and I think we make it clear that the individual efforts that people make to insulate their houses and drive a Prius or whatever, are good things, but in order to really change the course of climate change, we really need a pretty serious overhaul in the way we make and use energy.

And no one technology is going to be able to do that, first of all. And I think a subtext is that it’s going to take action at the level of governance to really make those kinds of changes. And we kind of hope that as the understanding of the real risk we run becomes clearer, the climate for government action will become easier.

I use the analogy of the anti-smoking campaigns. You know, if, in 1964 when the first Surgeon General’s report came out, if you had told me, ‘one day you will have no smoking anywhere,’ people would have been outraged. And with the growing realization that smoking really was a dangerous thing, and is a dangerous thing, when governments finally did start to take these actions, there was very little outcry. And I believe that kind of broad social acceptance of a fact that emitting carbon is socially unacceptable, is going to be necessary before the government can take such action.

CURWOOD: Now this book is for a lay audience and yet you subjected it to fairly rigorous peer scientific review, like it was going to go into a fancy scientific journal. Why did you do that?

LEMONICK: We did that because we felt very strongly that we did not want to be putting statements out there that weren’t scientifically defensible. Because that just gives skeptics a huge target; it’s like painting a kick-me target on your back, and would enable skeptics to suggest that the whole book was invalid because there might be an exaggerated statement about something.

And we just didn’t want to take that risk, and we didn’t feel we needed to because the basic, unvarnished facts are serious enough. So we wanted to make sure that the actual science, even though simplified, was pretty much bomb-proof when we put out the book.

CURWOOD: Michael Lemonick is a senior science writer at Climate Central. The new book is called, “Global Weirdness: Severe Storms, Deadly Heat Waves, Relentless Drought, Rising Seas, and the Weather of the Future.” Thanks so much, Mike.

LEMONICK: Thank you, it’s been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Global Weirdness

- Climate Central

[MUSIC: Bombay Dub Orch “Monsoon Malabar” from 3 Cities (Six Degrees Music 2008)]

Great Blue Heron

(Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Great Blue Heron rookeries are frequently found in beaver ponds. The trees that drown as a result of the beaver’s enterprise provide perfect nest sites, but only wide, deep ponds that provide safety and separation from shore will do, and these are increasingly uncommon.

They grab her bill, and eventually she disgorges into the nest or right down the throat of one of the chicks. At this age it's usually into the nest so they all can eat. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Writer Mark Seth Lender has spent years searching for a heron rookery—and eventually he found one, just off the Connecticut River, with more than a dozen nests and many Great Blue Herons.

LENDER: The dead oaks spread against the sky like mouths: lips thin as a spindle, grey as their own demise. Dry and cracked and begging for rain though they stand in a pond of water, thirsty though they have drowned. And it is not rain that will come to them, that will purpose this long last stand of their being. Although, like rain, it will come from the clouds, and the color of clouds.

[THE SOUNDS OF GREAT BLUE HERONS]

(Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

In the still air, in guttural blue plumage swirling and shuddering in grey come whispering, rolling like fog, Great Blue Herons! And they glide and glide then pull up straight, waving wide, grey-blue arms, and all in slow motion. Then grasp the thin dead branches, wingtips spread broad as a balance bar, the tightrope quavering in their light and thin-legged touch.

And do not settle but stand tall now in salutation, bright bills upraised… each toward the other, mouths open like branches, necks reaching, Great Blue Herons, lovers never touching as if yearning like a thirst never quenched except in the liquid of the eyes. For the Herons have no water, but neither have they brought fire. And in their mouths they bring only branches, to be woven like baskets, to hold and caress the source of themselves. Oval. Perfect. In the shape of the world before it was born and blue as a pale blue sky.

Patient and practiced, now until the shell breaks open, it will open like a flower to breathe and unfold the feathers like petals, Great Blue Heron emerging small and imperfect to become, the only real and perfect mirror of the self.

(Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

And so continue, until in time, all this is taken and Great Blue Herons pass from this place like a whisper in thin, in blue, in air.

[MUSIC: Clare Connors “Flight Of The Heron” from Heartlight (Heartlight Creations 2005)]

CURWOOD: Mark Seth Lender is the author of Salt Marsh Diary—A Year on the Connecticut Coast. To see photos of the herons, swoop over to our website, LOE dot org.

[MUSIC CONTINUES]

CURWOOD: Coming up—nature's skill at making green things grow might just be the key to more efficient solar cells. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Breckinridge Capital Advisors, applying a sustainable approach to fixed income investing, www.breckinridge.com, the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and Gilman Ordway, for conservation and environmental change. This is Living on Earth on PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Christian Scott: “When Marissa Stands Her Ground” from Christian Atunde Adjuah (Concord Music group 2012)]

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth - I'm Steve Curwood.

[SFX POPEYE THEME]

Spinach Power

(Julie Turner/Vanderbilt)

CURWOOD: Popeye claimed that spinach was the key to bulging biceps, but researchers at Vanderbilt University have just found a new use for the super-vegetable, harnessing the power of the sun.

Kane Jennings teaches Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at Vanderbilt University. With his colleague Professor David Cliffel, he has developed a new way to use proteins found in spinach to generate solar power. He joins us now from Nashville. Professor, welcome to Living on Earth.

JENNINGS: Thank you very much, I'm glad to be here.

CURWOOD: So, it sounds like Popeye was right… spinach really is strong to the finish…

JENNINGS: That’s absolutely true!

CURWOOD: Now, how do you get juice out of spinach… the electric type… what exactly have you developed here?

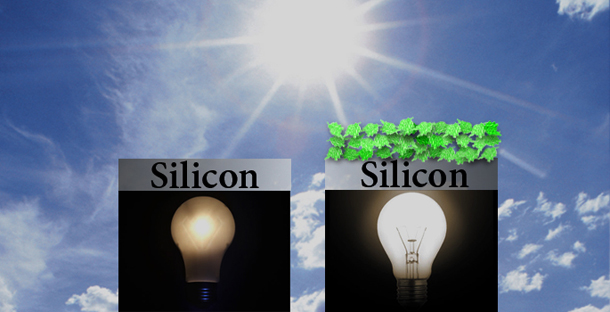

JENNINGS: What we did was extract out a key protein found in spinach and all other green plants known as photosystem 1. We placed photosystem 1 on a surface, it’s able to capture incoming light, much like it does in photosynthesis – both current and potential – to power a solar cell.

CURWOOD: What made you think, though, of using vegetables to make solar cells?

JENNINGS: Well, photosynthesis, if you look at the rate of power of all of the photosynthesis on the planet… it is eight times greater than all of the power we are developing through fossil fuels at the moment. So photosynthesis is just a giant solar conversion process out there in nature. So, therefore, we want to use green plants that are very well known for capturing the sun’s light and producing power.

CURWOOD: What makes your spinach solar cells more productive than other bio-hybrid solar cells?

JENNINGS: We have found that if we place this protein onto a positively built silicon electrode, that we get 2,500 times more power than if we placed this protein film onto a metal electrode. We’ve also found that we get six times more power out over just a silicon electrode alone.

CURWOOD: You’re saying that, by using spinach, you can have solar cells that are basically six times more powerful than what’s on some people’s roofs right now?

A team of senior undergraduates from Vanderbilt made a 2 ft by 2 ft solar panel out of spinach-based Photosystem to win three awards at the EPA's National Sustainable Design Exposition. (Vanderbilt University)

JENNINGS: Not exactly. Because, what we’re…. in that case we’re comparing apples to oranges. What’s on folk’s roofs right now would be a silcon-based photovoltaic, which is a very solid-state type device. What we’re looking at here is more of a wet-based solar cell. More like kind of a solar battery, where you’ve got small cells that act to transfer the power away from the protein film.

CURWOOD: But power-wise, how does this compare to the conventional cells that we have today?

JENNINGS: We’re not quite in the conversation at this point, with say, conventional PVs. What we have shown is that we’ve increased the power output on these simple liquid-based solar cells by a million-fold in the last five years. If we stay on this same trajectory, we’ll be very close to those more traditional photovoltaics in about three years.

CURWOOD: And spinach is cheaper than silicon?

JENNINGS: Spinach is very affordable, that’s right.

CURWOOD: Now, spinach is a very nutritious vegetable, we don’t always like to of course… what impact does that have on its uses for solar energy. I mean, might there be a tighter spinach market once this gets going?

JENNINGS: Yes, what I would really like to see long-term is if we are able to continue to make these substantial improvements in our performance, is for us to shift away from traditional food sources like spinach, and ultimately use energy sources that are non-food based. For example, we are now working on a project where we can actually extract photosystem 1 from kudzu.

CURWOOD: Ah!

JENNINGS: Now, kudzu is an invasive, rapidly growing vine that covers many millions of acres in the southeastern United States.

CURWOOD: So, Professor Jennings, how far away are we today from having commercially marketable spinach, or, say, kudzu, solar cells?

JENNINGS: I would say that we are about, in the neighborhood of five to ten years, of having commercially marketable solar cells based on bio-hybrid technology. We need to make performance improvements to get us much closer to what traditional photovoltaics are giving out right now. And we need to really investigate all of the materials issues to make sure that we’re getting the highest efficiencies we can out of these systems.

CURWOOD: Before we go, do you think SweetPea would approve?

JENNINGS: I think SweetPea would be happy to know that we are getting alternative types of power out of spinach.

CURWOOD: Kane Jennings is Professor of Chemical and Bimolecular Engineering at Vanderbilt University, thank you so much, professor.

JENNINGS: Thank you very much, I've enjoyed this.

Related links:

- A Link to the Full Paper

- Vanderbilt Press Release

[POPEYE THE SAILOR MAN, THEME SONG]

Bagging Big Trees

Every year the non-profit American Forests updates their registry of the biggest trees of each species in the country. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb learns how to measure champion trees.

CURWOOD: OK - when you think about hunting big game you probably think - lions or buffalo but there is a small enthusiastic group of people who think…. trees. Every year the non-profit American Forests releases an online registry of the biggest trees in the country. There are more than 660 species of native trees on the registry, nominated by foresters and average citizens alike. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb met up with a tree hunter in West Hartford, Connecticut.

[PARK AMBIANCE UNDER GRAPH, PEOPLE MURMURING]

RICHARDSON: When I first started in this game in 1987 I knew something about trees but…..

BASCOMB: Ed Richardson’s not exactly the picture of a big game hunter but he’s bagged more big trees than anyone else in the state of Connecticut. We meet at a city park in West Hartford where he shows me his itinerary for the day.

RICHARDSON: We’re going to measure a large tree in the park here, in Elizabeth Park. Then I thought we’d stop by the Pinchot Sycamore, which is the largest tree in New England, of any kind….and, it’s a monster.

BASCOMB: Ed Richardson is a retired insurance salesman. He wears hiking shoes and khaki pants with a striped shirt tucked in. He says the best place to hunt for big trees is in urban areas: old estates, cemeteries, and college campuses. Most American forests have been cut down several times over for farming.

[PARK AMBIANCE]

RICHARDSON: So, you don’t really find many big trees in the woods.

[AMBIANCE, WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: He leads the way down a path in the park to a wooded area. He wants to re-measure the state champion Golden Larch to be sure it’s still the biggest.

RICHARDSON: And we’re going to see how big this is.

BASCOMB: Ed walks around the tree with a tape measure.

RICHARDSON: And this is eight feet seven inches in circumference.

BASCOMB: The scoring for to become a champion tree is a bit complicated. For every inch of circumference a tree gets one point. They get another point for every foot of height. And a quarter point for every foot of canopy spread. To measure the height Ed needs a clear view of the top of this Golden Larch.

RICHARDSON: I’m going to go down in that direction which is the only direction that I can possibly see through the canopies here.

BASCOMB: He pins the end of the tape measure to the base of the tree and measures out 100 feet down a path.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: He pulls out a rectangular silver case.

RICHARDSON: Ok, here’s what we do. My chlenometer is a little thing about the size of a pack of cigarettes, I guess you might say, if anyone knows what those are now a days. But what I do is look through at the scale inside there. Come on baby, what are you doing? Don’t tell me you’re in trouble. Boy, I don’t know.

BASCOMB: Can I help you?

RICHARDSON: I’m having trouble with it. Not with the machine. It’s my eye is the problem. Why don’t you take a try at it?

BASCOMB: OK

RICHARDSON: Don’t put your finger over the end because you’re looking through that little hole there. Take a look first off and see if you see a little wheel in there or whatever the thing is that goes around.

BASCOMB: Yeah

RICHARDSON: Go up and down like this and see if the numbers change.

BASCOMB: They do. So, it’s like a white tape measure on a wheel kind of thing.

RICHARDSON: That’s right, boy that’s a good description. A white tape-measure. Right. Now take a shot at the base of that tree. You’re looking at the base with your left eye and you’re looking at the crosshair with your right eye.

BASCOMB: Ahh…so you have both eyes open.

RICHARDSON: Right, both eyes open.

RICHARDSON: You have to have two eyes to use this thing.

BASCOMB: (laughs) OK.

BASCOMB: OK, oh it goes backwards so 90 is at the top and then it goes down to 100.

RICHARDSON: That’s right.

BASCOMB: Ok, the scale is by …2,4,6….102?

RICHARDSON: Ah! That’s good! That’s good! I’m sure that’s right around what it is. It’s probably grown a hair since I measured it last.

[MEASURING TAPE WINDING UP]

BASCOMB: Ed winds his measuring tape back to the base of the tree where picks his way through the brush to measure the width of the canopy above us.

RICHARDSON: Don’t go in here. That’s poison ivy, I see it.

BASCOMB: Ed comes up with 13 points for the canopy. Add to that 103 points for circumference and 102 points for height.

RICHARDSON: Three into five is eight….one….218 points for this tree. It remains the champion and probably always will unless it gets blown down or something.

[WOODS AMBIANCE, WALKING CROSS FADE WITH STREET SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Next he wants to check out a large, Asiatic Smoke bush. The bush is in front of a Sovereign Bank that used to be a Colonial home, built in 1780.

[ROAD SOUNDS, CAR GOES BY]

RICHARDSON: This is it. Boy, that’s a big one.

BASCOMB: Together we measure the height, circumference and canopy spread.

RICHARDSON: Would you just hold this? That’d be good. I think I can rig this around.

BASCOMB: And it earns a total of 78 points.

RICHARDSON: So, we’re going to go up to the car and look at the computer listing and see how many points the present state champion has.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: There are 861 native tree species listed on the national registry. But more than 200 of them have no champion right now. So, the first person to nominate a Western Burningbush or a Seaside Alder, for instance, would have a national champion.

[CAR OPENING SOUNDS]

RICHARDSON: Alright, this is the master list. We’re going to look for the botanical name which is a strange one it’s Cotinus coggygria.

[PAGES FLIPPING]

RICHARDSON: There it is right there. The champion is 50, we’ve got 78. This goes way beyond it. So, we’ve got a new state champion here. Great, ok!

BASCOMB: Richardson’s found more than 150 state champion trees so this is all in a day’s work for him. But he says some people are extremely competitive.

RICHARDSON: Oh, in some states, they’re just wild, they’re obsessed with it.

SMITH: I’ve got a bee in my bonnet about Tennessee.

BASCOMB: Pete Smith is the national big tree coordinator for the state of Texas. The bee in his bonnet is about a pecan, the state tree of Texas. Currently Tennessee has the national champion pecan tree.

SMITH: A tree that I may need to go visit. Some disputed idea that it may be an English walnut rather than a pecan but I’m just throwing that out there.

BASCOMB: Pete Smith has been known to drive to other states to question the legitimacy of a big tree.

SMITH: One of our national champion cottonwood trees here in Texas where New Mexico challenged it, and it was going to be crowned a national champion. And I actually had our forester from El Paso drive up to Albuquerque and measure the tree to make sure it was measured the same as our tree.

BASCOMB: And was it?

SMITH: No! Our tree ended up staying the national champ.

BASCOMB: Pete’s not alone in the Lone Star State when it comes to his enthusiasm for big trees.

SMITH: In a big game state like Texas where hunting is a big part of the culture here I think it sort of resonates with those folks to bag another trophy so to speak.

BASCOMB: Texas has enthusiasm, but California has the single largest tree in the country and the world. General Sherman is a giant sequoia that registers a whopping 1300 points on the American Forest Champion Scale. But even California doesn’t have the most big trees on the national register. With 124 national champs that honor goes to… Florida. Charlie Marcus is the national big tree coordinator for the state of Florida.

MARCUS: We have a number of species that don’t grow in any other states because our southern regions go down into the tropics.

BASCOMB: More than half of Florida’s champion trees live in the bottom third of the peninsula and don’t grow anywhere else in the country. So, there’s not much competition. But all this talk of big trees really begs the question: Is bigger better?

MARCUS: By all means.

BASCOMB: Again, Charlie Marcus.

MARCUS: Those trees become micro-habitats all their own. There so old that you’ve got soil that’s actually formed there and you’ve got plants that are growing out of the soil and you’ve got animals that are kind of dependent on those plants and those conditions for a micro-climate. I would say a large tree takes on a life of its own, and in most cases bigger probably is better.

BASCOMB: Big old trees can also tell us something about resilience. Starting in 1930 Dutch Elm disease practically eradicated North American Elm trees but some did survive. Now USDA scientists are looking at the immunity of those old living trees hoping to develop more disease resistant Elms.

BASCOMB: Back in Connecticut Ed Richardson wraps up the day with a visit an old favorite.

RICHARDSON: This is the Pinchot Sycamore. It’s the largest tree of any kind in New England. And it’s a monster.

BASCOMB: What do you think of when you look at trees that are this big and this old?

RICHARDSON: Well, it’s just a magnificent historical relic. I like their strength and their nobility. They’ve existed a long time on this Earth and more are coming along, hopefully, if people will treat them right.

BASCOMB: And, that’s the aim of the American Forests competition. To create a passion for conservation…. so more little trees reach their full potential to grow into big trees in the future. For Living On Earth I’m Bobby Bascomb in Simsbury, Connecticut.

Related links:

-

- American Forests

[MUSIC: Quantic “Trees And Seas” from Mishaps Happening (Tru Thoughts Ltd. 2004)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Bruce Gellerman, Helen Palmer, Jessica Ilyse Kurn, and Ike Sriskandarajah, with help from Meghan Miner, Gabriela Romanow and Sammy Sousa. We welcome a new intern, Emmett Fitzgerald this week – glad to have you aboard. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at L-O-E dot org , and check out our Facebook page… it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science. And Stonyfield Farm, organic yogurt and smoothies. Stonyfield invites you to just eat organic for a day. Details at just eat organic dot com. Support also comes from you, our listeners, the Go Forward Fund, and Pax World Mutual and Exchange-Traded Funds, integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at pax world dot com. Pax world, for tomorrow.

PRI ANNOUNCER: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth